Covid & the 4k’s: 4 Foods “Many People Don’t Know About”

Renowned professor, epidemiologist and author of The Diet Myth and Spoon Fed Tim Spector is encouraging people to eat the 4k’s: kefir, kombucha, kimchi and kraut. His studies found diet plays a role in preventing severe symptoms of Covid.

Spector is a leading expert on long Covid, the symptoms that can continue for extended periods after an initial infection. He leads the ZOE Covid Study, created by scientists and doctors at King’s College London (where he is based), Stanford, Harvard, Massachusetts General Hospital and health science company ZOE. Last year Spector helped research the attributes and predictors of long Covid, the results of which were published in the journal Nature Medicine.

A microbiome researcher, Spector advocates for people to eat a diverse diet to improve the trillions of microbes in the gut.

“We know from Covid now that your gut health is crucial for your immune system,” he told ITV. “If we can focus on our gut health…gut microbiome is really crucial.”

Diet must be high-quality to improve immunity, he stresses. In the ZOE Covid study, researchers have found eating “the right things and avoiding feeding (the gut) the bad things, that’s what made the difference to getting long Covid,” he said. Fermented foods have proven health benefits, but Spector says many people opt for cheaply-made yogurts and cheeses prevalent in the grocery store to get their daily dose of fermented foods. This dairy is full of sugar and artificial ingredients, which thwart the positive effects of fermentation.

“The other fermented foods that many people don’t know about are what I call the 4 k’s,” Spector says: kefir, kombucha, kimchi and kraut (sauerkraut). He encourages “small shots a day” of a fermented food or beverage. “That really is a powerful enhancer of your microbes. And all these things are going to be cheaper actually than taking multivitamins every day of your life.”

Spector is not a fan of supplements, like pill forms of vitamins and nutrients. Many are proven not to work, he explained. In his studies on the effects of supplements on long Covid, there were minimal benefits for women and none for men.

“People are much better off getting all their vitamins and nutrients by having a diverse diet,” Spector said.

- Published in Food & Flavor, Science

SCOBY as Water Filter?

Can you use bacteria to eliminate bacteria? Commercial water filters remove contaminants from water, but the pores eventually clog, causing water to filter more slowly. Now researchers are studying a living membrane to filter water: a kombucha SCOBY.

Researchers at Montana Technological University (MTU) and Arizona State University (ASU) found the films of cellulose that make up a SCOBY are 19-40% more effective than commercial filtration systems at preventing the formation of bacterial biofilms. The SCOBY filter also maintained a fast rate of filtration for a longer period of time. Though a biofilm did eventually form on top of the SCOBY, it contained fewer bacteria than in a commercial filter.

“The scientists couldn’t use the wild yeasts typically used in kombucha because the yeasts are difficult to modify genetically,” reads an article in Wired. “Instead, the researchers used lab-grown yeast, specifically a strain called Saccharomyces cerevisiae, or brewer’s yeast. They combined the brewer’s yeast with a bacteria called Komagataeibacter rhaeticus (which can create a lot of cellulose) to create their ‘mother’ SCOBY.”

Researchers engineered the cells in the yeast to produce glow-in-the-dark enzymes, which sense pollutants and break them down. SCOBY-based filters are not only inexpensive to make, they biodegrade when discarded.

Their research was published in the American Chemical Society journal ACS ES&T Water.

Read more (Wired)

Retail Sales Trends for Fermented Products

Miso, frozen yogurt and pickled and fermented vegetables are driving growth in the $10.97 billion fermented food and beverage category. The fermented products space grew 3.3% in 2021, outpacing the 2.1% growth achieved by natural products overall.

“It really highlights how functional products have become the norm for shoppers when they’re in stores,” says Brittany Moore, Data Product Manager for Product Intelligence at SPINS LLC, a data provider for natural, organic and specialty products. Moore notes there’s an “explosion of functional products” in the market — “[they] are appearing everywhere. And fermented products have been leading that space in the natural market for years.”

The data was shared during TFA’s conference, FERMENTATION 2021. SPINS worked with TFA to drill into data covering 10 fermented product categories and 64 product types (an increase from last year). [A note that wine, beer and cheese sales are excluded from the data. These categories are very large, and would obscure trends in smaller segments. Wine, beer and cheese are also well-represented by other organizations.]

Yogurt dominates the fermented food and beverage landscape with 75% of the market, but sales growth is soft. Frozen yogurt and plant-based offerings, though small portions of the yogurt category, are fueling what growth there is. “Novelty products are catching shopper’s eyes,” Moore notes.

Kombucha, the fermented tea which led the U.S. retail revival of fermented products, still rules the non-alcoholic fermented beverages market, with 86% of sales. But growth is slowing. Moore points out that this slowdown is due to kombucha having penetrated the mass market with lots of brands on grocery shelves.

“There’s opportunity in kombucha for new innovations to catch the progressive shopper’s eye,” Moore says. “Shoppers are looking for an innovative twist to their functional product.”

Moore points to successful twists like hard kombucha, which grew nearly 60%, and probiotic sodas, which grew 31%.

Growth is slowing for hard cider, too, though hard cider leads the alcoholic beverages category with 83% share of sales.

All sectors of the pickled and fermented vegetables category are growing, totalling nearly $563 million in sales. Refrigerated products are nine of the top 10 subcategories here. The “other” pickled vegetable subcategory is increasing at a 60% growth rate, “other” being the catch-all for vegetables that are not cucumbers, cabbage, carrots, tomatoes, beets or ginger. Fermented radish, garlic and seaweed fall into this subcategory.

Soy sauce is not surprisingly still the largest product in sauces, representing 58% of the category. But that share is dropping. Gochujang is the growth leader, increasing at rate of nearly 20%.

Miso and tempeh are also performing well, which Moore attributes to the growing plant-based movement and the Covid-19 pandemic pantry stocking boom. Miso products — soups, broths, pastes and mixes — totaled over $24 million in sales in 2021. Though instant soups and meal cups represented only 8% of sales, they grew more than 110%.

- Published in Business

“Our Customers Do Not Even Know What is a Fermented Item”

Fermentation is cloaked in mystery for many — it’s bubbly, slimy, stinky and not always Instagram-ready. In The Fermentation Association’s recent member survey, this lack of

understanding of fermentation and its flavor and health attributes among consumers was cited by 70% of producers as a major obstacle to increased sales and acceptance of fermented products.

“We get so many questions from our readers about fermentation. People are very interested, but have very, very little knowledge about it,” says Anahad O’Connor, reporter for The New York Times. O’Connor has written about fermented foods multiple times in the last few months, and those articles were among The Times’ most emailed pieces of 2021. “I think there’s a huge opportunity to educate consumers about fermented foods, their impact on the gut and health in general.”

O’Connor spoke on consumer education as part of a panel of experts during TFA’s conference, FERMENTATION 2021. Panelists — who included a producer, retailer, scientist, educator and journalist — agreed consumer education is lacking. But the methods of how to fill that gap are contested.

How to Tell Consumers “What is a Fermented Food?”

There are differences between what is a fermented product and what is not — a salt brine vs. vinegar brine pickle, or a kombucha made with a SCOBY or one from a juice concentrate, for example.

“I can tell you that the majority of our customers do not even know [what is a] fermented item,” says Emilio Mignucci, vice president of Philadelphia gourmet store Di Bruno Bros., which specializes in cheese and charcuterie. When customers sample products at the store, they can easily taste the differences between a fermented and a non-fermented product, Mignucci says. But he feels the health benefits behind that fermented product are not the retailer’s responsibility to communicate. “I need you guys [producers] to help me deliver the message.”

“Retailers like myself, buyers, we want to learn more to be able to champion [fermented foods] because, let’s face it, fermented foods is a category that’s getting better and better for us as retailers and we want to speak like subject matter experts and help our guests understand.”

Now — when fermentation tops food lists and gut health is mainstream — is the time for education.

“This microbiome world that we’re in right now is sort of a really opportune moment to really help the public understand what fermented foods are beyond health,” says Maria Marco, PhD, professor of food science at the University of California, Davis (and a TFA Advisory Board Member).

Kombucha Brewers International (KBI) created a Code of Practice to address confusion over what is or is not a kombucha. KBI is taking the approach that all kombucha is good, pasteurized or not, because it’s moving consumers away from sugar- and additive-filled sodas and energy drinks.

“That said, consumers deserve the right to know why is this kombucha at room temperature and this kombucha is in the fridge and why does this kombucha have a weird, gooey SCOBY in it and this one is completely clear,” says Hannah Crum, president of KBI. “They start to get confused when everything just says the word ‘kombucha’ on it.”

KBI encourages brewers to be transparent with consumers. Put on the label how the kombucha is made, then let consumers decide what brand they want to buy.

Should Fermented Products Make Health Claims?

Drew Anderson, co-founder and CEO of producer Cleveland Kitchen (and also on TFA’s Advisory Board), says when they were first designing their packaging in 2013, they were advised against using the term “crafted fermentation” on their label because it would remind consumers of beer or wine. But nowadays, data shows 50% of consumers associate the term fermentation with health.

“In the last five to six years, it’s changed dramatically and people are associating fermentation as being good for them, which is good for my products,” he says.

Cleveland Kitchen, though, does not make health claims on their fermented sauerkraut, kimchi and dressings. Anderson says, as a small startup, they don’t have the resources to fund their own research. They instead attract customers with bold taste and striking packaging.

“We’re extremely cautious on what we say on the package because we don’t have an army of lawyers like Kevita (Pepsi’s Kombucha brand), we don’t have the Pepsi legal team backing us here,” Anderson says. Cleveland Kitchen submits new packaging designs in advance to regulators, to make sure they’re legally acceptable before rolling them out.

O’Connor says taste is the No. 1 driver for consumers. This is why healthful but sticky and stinky natto (fermented soybeans) is not a popular dish in America, but widely consumed in Japan.

“Many American consumers, unfortunately, aren’t going to gravitate toward that, despite the health benefits,” he says.

Crum disagrees. “Health comes first,” she says. As more and more kombucha brands emphasize lifestyle, and don’t even advertise their health benefits, she feels they are doing a disservice to the consumer. “Why pay that much money for kombucha if you don’t know it’s good for you too?”

- Published in Business, Food & Flavor, Health, Science

Fermentation Tourism

The state of Pennsylvania has created a unique tourist experience, Pickled: A Fermented Trail. The self-guided, culinary tour showcases fermented food and drink from around the state.

The fermented trail is broken into five regional itineraries, and includes historic businesses, artisanal food makers and large producers. Stops range from an Amish gift shop that ferments root beer to a master chocolatier, from a kombucha taproom to a fermentation-focused restaurant, and from a fourth-generation cheesemaker to a convenience store that makes its own pickles, sauerkraut and vinegar. Mary Miller, cultural historian and professor, spent two years designing the trail.

“Cultured foods have been part of PA’s culinary culture since the beginning,” reads the Visit Pennsylvania Pickled: A Fermented Trail website. “Many groups that have migrated to Pennsylvania throughout history were fond of fermented foods for both health and flavor, as well as for preserving food through the winter.”

The website also features a history of fermented food and drink, both regionally and globally. It shares a brief overview of root beer, which was created in Pennsylvania as a sassafras-based, yeast-fermented root tea. And it notes that, while Germans brought sauerkraut to the state, the Chinese are believed to have been the first to ferment cabbage.

The fermented trail is one of Pennsylvania’s four new culinary road trips, along with those highlighting charcuterie, apples and grains. These paths aim to showcase the state’s culinary history, and preserve its foodways.

This unique culinary adventure — the first we have seen at TFA — could be a model for tourism in other states and countries.

Read more (Food & Wine)

- Published in Business

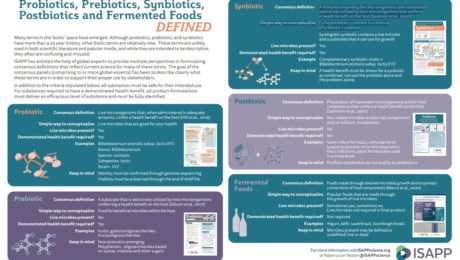

The Rise of Fermented Foods and -Biotics

Microbes on our bodies outnumber our human cells. Can we improve our health using microbes?

“(Humans) are minuscule compared to the genetic content of our microbiomes,” says Maria Marco, PhD, professor of food science at the University of California, Davis (and a TFA Advisory Board Member). “We now have a much better handle that microbes are good for us.”

Marco was a featured speaker at an Institute for the Advancement of Food and Nutrition Sciences (IAFNS) webinar, “What’s What?! Probiotics, Postbiotics, Prebiotics, Synbiotics and Fermented Foods.” Also speaking was Karen Scott, PhD, professor at University of Aberdeen, Scotland, and co-director of the university’s Centre for Bacteria in Health and Disease.

While probiotic-containing foods and supplements have been around for decades – or, in the case of fermented foods, tens of thousands of years – they have become more common recently . But “as the terms relevant to this space proliferate, so does confusion,” states IAFNS.

Using definitions created by the International Scientific Association for Postbiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP), Marco and Scott presented the attributes of fermented foods, probiotics, prebiotics, synbiotics and postbiotics.

The majority of microbes in the human body are in the digestive tract, Marco notes: “We have frankly very few ways we can direct them towards what we need for sustaining our health and well being.” Humans can’t control age or genetics and have little impact over environmental factors.

What we can control, though, are the kinds of foods, beverages and supplements we consume.

Fermented Foods

It’s estimated that one third of the human diet globally is made up of fermented foods. But this is a diverse category that shares one common element: “Fermented foods are made by microbes,” Marco adds. “You can’t have a fermented food without a microbe.”

This distinction separates true fermented foods from those that look fermented but don’t have microbes involved. Quick pickles or cucumbers soaked in a vinegar brine, for example, are not fermented. And there are fermented foods that originally contained live microbes, but where those microbes are killed during production — in sourdough bread, shelf-stable pickles and veggies, sausage, soy sauce, vinegar, wine, most beers, coffee and chocolate. Fermented foods that contain live, viable microbes include yogurt, kefir, most cheeses, natto, tempeh, kimchi, dry fermented sausages, most kombuchas and some beers.

“There’s confusion among scientists and the public about what is a fermented food,” Marco says.

Fermented foods provide health benefits by transforming food ingredients, synthesizing nutrients and providing live microbes.There is some evidence they aid digestive health (kefir, sourdough), improve mood and behavior (wine, beer, coffee), reduce inflammatory bowel syndrome (sauerkraut, sourdough), aid weight loss and fight obesity (yogurt, kimchi), and enhance immunity (kimchi, yogurt), bone health (yogurt, kefir, natto) and the cardiovascular system (yogurt, cheese, coffee, wine, beer, vinegar). But there are only a few studies on humans that have examined these topics. More studies of fermented foods are needed to document and prove these benefits.

Probiotics

Probiotics, on the other hand, have clinical evidence documenting their health benefits. “We know probiotics improve human health,” Marco says.

The concept of probiotics dates back to the early 20th century, but the word “probiotic” has now become a household term. Most scientific studies involving probiotics look at their benefit to the digestive tract, but new research is examining their impact on the respiratory system and in aiding vaginal health.

Probiotics are different from fermented foods because they are defined at the strain level and their genomic sequence is known, Marco adds. Probiotics should be alive at the time of consumption in order to provide a health benefit.

Postbiotics

Postbiotics are dead microorganisms. It is a relatively new term — also referred to as parabiotics, non-viable probiotics, heat-killed probiotics and tyndallized probiotics — and there’s emerging research around the health benefits of consuming these inanimate cells.

“I think we’ll be seeing a lot more attention to this concept as we begin to understand how probiotics work and gut microbiomes work and the specific compounds needed to modulate our health,” according to Marco.

Prebiotics

Prebiotics are, according to ISAPP, “A substrate selectively utilized by host microorganisms conferring a health benefit on the host.”

“It basically means a food source for microorganisms that live in or on a source,” Scott says. “But any candidate for a prebiotic must confer a health benefit.”

Prebiotics are not processed in the small intestine. They reach the large intestine undigested, where they serve as nutrients for beneficial microorganisms in our gut microbiome.

Synbiotics

Synbiotics are mixtures of probiotics and prebiotics and stimulate a host’s resident bacteria. They are composed of live microorganisms and substrates that demonstrate a health benefit when combined.

Scott notes that, in human trials with probiotics, none of the currently recognized probiotic species (like lactobacilli and bifidobacteria) appear in fecal samples existing probiotics.

“There must be something missing in what we’re doing in this field,” she says. “We need new probiotics. I’m not saying existing probiotics don’t work or we shouldn’t use them. But I think that now that we have the potential to develop new probiotics, they might be even better than what we have now.”

She sees great potential in this new class of -biotics.

Both Scott and Marco encouraged nutritionists to work with clients on first improving their diets before adding supplements. The -biotics stimulate what’s in the gut, so a diverse diet is the best starting point.

Redzepi: “Fermenting is our future”

An interesting indication of how quickly and decisively fermentation is moving into the U.S. food mainstream is a recent online event organized and offered by American Express and restaurant booking service Resy, “A Fermentation Workshop with Noma.” For $50, one could sign up for an hour-long Zoom — introductions from Noma’s René Redzepi and Jason White, and demonstrations of making lacto-fermented tomatoes and a juice-based kombucha, all moderated by renowned food writer Ruth Reichl — and a copy of 2018’s “The Noma Guide to Fermentation.” The event sold out in minutes.

Redzepi (Noma chef and co-owner) and White (Noma’s head of fermentation) were in their fermentation lab at the restaurant, and gave concise, compelling comments on the long history of fermentation and its importance. They noted the healthful aspects of the process but emphasized its ability to produce delicious flavors.

“One of the most important things for me as a fermenter is definitely having a closer look at nature, and also being able to create new and interesting flavors that can have beneficial effects on humans, meaning it can make us healthier, it can make our dinners more exciting and also we can teach future generations how they can interact with nature as well,” White says. “The power of fermentation is a really good bridge to that because, in one way or another, in every culture, in every place on earth, there are people who have been doing it for thousands of years. I think it’s important for us to carry the torch. And I think carrying the torch of fermentation is definitely my biggest dream, to carry it for another thousand years.”

When Noma opened over 18 years ago, it was in the dead of winter and they struggled to deliver meals made from Nordic ingredients. “We were really desperate to find food,” Redzepi continues. By spring, they began foraging, “it grounded us and gave us direction.” A few years into foraging, they wondered how they could take the abundance of spring and summer ingredients and use it in the long winter season.

“That’s when we started dabbling into fermentation,” he says. “And from that moment on, a whole new world opened up for restaurant Noma. You could even say fermentation eclipsed foraging because we found out, through the yeast and the mold and the bacterias, we could simply create such new flavors that would transform our kitchens forever. We started tapping into the community worldwide of fermenters and traditional fermentations, adapting them to our ingredients and our region and thus creating a new set of tools that has really engrained itself into every single Noma dish. You don’t eat anything at Noma that doesn’t have ferments in them.”

“Instead of food waste, you can ferment it into something delicious,” he adds.

They made the recipes seem easy to execute (though I suspect the presentation of SCOBY might have put off some participants). And, to ensure at least a small dose of titillation, they proffered a container of one current project in the lab, “Reindeer Penis Garum.” They used this as an example of how fermentation can minimize waste by finding applications for what would otherwise be scrap or trash.

The detailed discussion of kombucha was illuminating, including an interesting contrast with vinegars. Noma makes numerous kombuchas, both for direct consumption and for use as an ingredient. Redzepi expressed his personal perspective, which helps explain why. He says he has yet to find a commercial product “that’s worth buying” — and it’s easy to make yourself.

It was great to see fermentation as a front-and-center topic, but there is still work to be done. The literature that was sent to all participants to accompany the presentation included references in the kombucha recipe to “backstop” and “backdrop” liquid — though they meant “backslop.”

- Published in Business, Food & Flavor

Former Felon Formulates “Fermented Felon”

Ex-con Tony Horner broke his imprisonment cycle by starting a kombucha brand. His fermented tea is sold at various grocery stores in the Omaha area. He now works with two local prisoner reentry programs that aim to help fellow ex-cons.

The Bellevue, Wash., resident served a 10-year prison sentence but struggled to find a basic job after his release. He was battling alcoholism, too, and turned to fermentation to heal his damaged liver.

Horner took fermentation classes and began brewing kombucha. He studied manufacturing practices and breweries, and worked as a bar manager to learn how a microbrewery functions. Once the pandemic hit, he officially launched his brand, Fermented Felon.

“I think I have a product here where I could actually make a difference in other people’s lives,” Horner says.

Read more (The Daily Nonpareil)

- Published in Business

Brewing Health & Flavor with Kombucha

Alesia Miller wanted her Soul Brew Kombucha to introduce the health benefits of the fermented tea to Black people.

“Doing a little research about the industry, I learned there weren’t a lot of Black people or Black women brewing kombucha. It left out a lot of people – these cultures I felt needed to be educated on the benefits of it,” Miller tells Milwaukee Magazine.

The first kombucha brand in Milwaukee, Soul Brew found a niche with unique flavor combinations.These include Ginger Mango Peach, Cherry Bomb and a flavor called “Black Lives Matter” (a combination of Blackberry, Lemon and Mango).

Read more (Milwaukee Magazine)

- Published in Food & Flavor

The Next Frontier in Kitchen Appliances

Is fermentation the next big home kitchen technique? As more restaurants hire directors of fermentation, consumers are inspired to experiment at home.

An article in The Spoon makes a case for the rise of home fermentation equipment, which makes the process “a little less mysterious.”

“Fermenting is still viewed as something of a black art. Part of it is the weird and slightly creepy terminology (mother, anyone?). Mostly, though, it’s also because the act of farming bacteria to create tasty and healthy new foods is a far cry from the usual activity of assembling and cooking our meals in our kitchen.”

The article interviewed two entrepreneurs making their own fermentation devices: Breadwinner (which helps bakers know when their sourdough starter is ready) and Hakko Bako (a fermentation appliance). The creators say their products are making fermentation easy, controlled and approachable. Tommy Cheung of Hakko Bako notes food trends usually start in Michelin restaurants, then trickle down to casual dining and finally end up at the home kitchen. “I definitely think (home fermentation devices) are going to be a huge part of the future.”

Read more (The Spoon)

- Published in Business