Sourdough Fermentation & Gut Health

Sourdough is being researched for its effectiveness in helping people with celiac disease and gluten sensitivities. Charlene Van Buiten, PhD, an assistant professor of food science and human nutrition at Colorado State University, shared how sourdough can alleviate problems with gut health in an article she wrote for Baking Europe.

The live, active cultures contained in fermented foods like kimchi, pickles, kombucha and yogurt have been scientifically proven to increase the diversity of microorganisms in the digestive tract. A recent study from researchers at Stanford found a diet rich in fermented foods decreases markers of inflammation.

The same health benefits cannot be attributed to sourdough, though, because the live microorganisms are killed during baking.

“As a result, the health benefits associated with sourdough bread are derived not from probiotics, but from the actions of the starter culture over the course of fermentation,” Van Buiten writes. The microorganisms present in starter cultures “have been shown to improve mineral bioavailability in sourdough bread in comparison to conventional yeast-fermented bread through the production of organic acids and enzyme phytase, which promote the degradation of anti-nutritional phytates found naturally in flour. “

Sourdough bread has other positive effects, too. The increased acidity of sourdough forms resistant starch, so starch is not converted to sugar by the gastrointestinal tract but instead “acts more like fiber.” Sourdough fermentation also increases the amount of free amino acids in bread, improving the protein digestibility. Sourdough bread made from starter cultures are also lower on the glycemic index.

Van Buiten points out case studies “have suggested that traditional sourdough fermentation can improve gastrointestinal tolerance to bread in comparison to conventional yeast fermentation,” but only for individuals with non-celiac gluten sensitivity. Few studies have explored how sourdough would impact someone with celiac. A study would need to explore gluten degradation within sourdough fermentation, a key sensitivity for individuals with celiac.

“Though no evidence currently exists where traditional artisanal sourdough fermentation provides protection against the harmful gluten peptides associated with celiac disease pathogenesis, scientists are exploring novel strategies to employ the known gluten-degrading capabilities of sourdough-derived microorganisms in the production of baked goods,” Van Buiten adds.

Read more (Baking Europe)

Electric Kombucha

In the last few years, entrepreneurial scientists have found creative uses for the kombucha SCOBY mother used to make new products. The latest: using SCOBY as a malleable surface to print circuit boards.

Researchers at the University of the West of England, Bristol, discovered the dried mats made from the cellulose of the SCOBY make flexible, cheaper, lighter and more eco-friendly circuit boards for electronics. And because these kombucha mats are non-conductive, they’re also safer. Andrew Adamatzky, professor at the university and one of the researchers, says they tested the SCOBY mat with tiny LEDs on the circuits, which still worked after stress tests.

“Nowadays kombucha is emerging as a promising candidate to produce sustainable textiles to be used as eco-friendly bio wearables,” Adamatzky, tells New Scientist. “We will see that dried — and hopefully living — kombucha mats will be incorporated in smart wearables that extend the functionality of clothes and gadgets. We propose to develop smart eco-wearables which are a convergence of dead and alive biological matter.”

Researchers hope kombucha electronics can soon be used as wearable electronics, like heart rate monitors.

The discovery is another in a unique lineup of SCOBY-based innovations. Alternative “leather” closes made from SCOBY were designed by an Iowa State professor in 2016, SCBOY water purifiers were designed by a Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Imperial College London scientists in 2021 and a SCOBY wood alternative called Pyrus was designed by University of Illinois student in 2021.

Read more (ARS Technica)

- Published in Science

Exploring Fermentation & Health with David Zilber

We cannot write-off pasteurized ferments as the dead, less healthy cousin to its unpasteurized, live relative. All fermented foods provide health benefits, pasteurized or not. We also need to avoid getting caught up in superfluous health claims around fermentation’s benefits. Instead, we should focus on including fermentation as part of a regular diet.

David Zilber explored how the microbial transformation of food intersects with our gut microbes during Stanford University’s Center for Human Microbiome Studies Fermentation & Health Speaker Series. With growing scientific interest in fermentation – and increasing interest from consumers – the health benefits become cloudy in marketing claims.

“If you eat regularly foods full of life, life that lives regularly in the foods you consume but also inside of you, then you can be said to be a ranger taking care of a healthy forest,” Zilber said. “The health benefits of fermented foods should equally be viewed as being meaningful when they turn into a regimen, like exercise.”

Health Claims

A 2021 study by Stanford researchers published in the journal Cell found regularly eating fermented foods boost microbiome diversity, improves immune response and decreases inflammation. But marketing of fermented products is often shrouded in hearsay.

“As far as health claims go…(there are) sometimes outlandish claims made by Westerners about cure-all superfoods that disproportionately, and I quote from one study I found, ‘Seemed to benefit the individuals that sell them the most,’” Zilber said.

Take kombucha, for example. He rattled off a list of health problems kombucha founders have claimed the fermented tea has cured, from AIDS to cancer to constipation.

“The problem is that all these claims seem to come, in one form or another, from anecdotes of people who drink kombucha and have lived a life,” he added. They’re not researched in reputable cohort studies. “This is why it’s sometimes hard to separate the wheat from the chaff when it comes to fermentation. The people who want to believe the benefits only decry its Praises when a positive correlation is made but they also tend to speak the loudest.”

Zilber pointed out that consuming fermented foods, whether or not it’s a product with proven health benefits, is certainly still beneficial. Eating fermented foods regularly means “you’re also omitting a whole slew of other foods” prevalent in a Western diet, like highly-processed and chemically-preserved foods.

“If you put kimchi on your plate at dinner, you leave off mashed potatoes. If you use water kefir as your drink with it, you aren’t drinking Coke,” he said. “And that’s an important link we also can’t forget, when it comes to thinking about the health benefits of fermented foods, they are in many means inherently healthy.”

Many cultures have fermented for thousands of years to preserve food. In Tibet, yak herders rely on cultural wisdom passed down from generations to ferment yak’s milk for milk and butter.

“We’ve evolved alongside our microbes both evolutionarily and culturally,” Zilber added. “To Tibetans their folk knowledge of what leads them to Long lives and health is intrinsically tied to the practices of preservation that have allowed them to thrive in some of the most rarified air on Earth.”

Pasteurized vs. Unpasteurized

What about purchasing pasteurized vs. unpasteurized ferments? Unpasteurized ferments include live microbes, but that doesn’t mean pasteurized ferments aren’t healthy.

“Sometimes in cooking, if you’re looking to achieve a great flavor, sometimes you have to kill microbes because you have to pasteurize them for whatever number of reasons,” Zilber added. But it doesn’t mean that the food is somehow not worth eating, it just means that it’s not live, but it still contains lots of benefits. … There is a benefit to consuming something that microbes have lived through, even if it’s not pasteurized.”

Elisa Caffrey, the speaker series host and a Stanford PhD candidate, agrees. The benefits of unpasteurized ferments have not been studied. During fermentation, Caffrey notes, the microbes are producing metabolites still present during pasteurization. A complete study would characterize the metabolites over the course of the fermentation process, identify chemical compounds and then analyze the compounds for their benefits.

“That landscape we don’t understand at all and it’s a very, very interesting world to start exploring,” she said. “Until we start understanding all the different components of these foods and the way that they interact with not only the microbes in fermented foods with each other but also with the body, it’s really hard to then make these very generalized health claims.”

Caffrey, Zilber and Justin Sonnenburg, PhD, professor of microbiology and immunology at Stanford, host the Fermentation & Health Speaker Series. The series will explore the topic over the next few months with different speakers ranging from a scientist, food researcher and pickle producer. Registration is free.

“Fermented Foods…Democratize the Science”

Though research about the gut-brain axis is a “growing, pioneering and still relatively novel field,” scientists say humans can improve their mental health by eating a balanced diet rich in fermented foods.

Changes in the gut microbiome can impact the brain’s behavior. Research advancements in the last 20 years “suggest that these (gut) microorganisms aren’t just a vital part of our physical selves, but also our mental and emotional selves, too.” This can be a major breakthrough in how mental health is treated.

For example, one study found individuals with depression have different gut bacteria compared to individuals without depression. Those without depression have a higher amount of bacteria associated with better wellbeing and quality of life. Antidepressants didn’t help. Another study found taking certain probiotic strains improve symptoms of depression and anxiety. And yet another study found taking prebiotics improved the brain’s cognitive function.

But research is still in its early stages. Though some strains of bacteria have been scientifically proven “to have a positive effect on the human mind,” researchers don’t know why and how. Genetics, personality and environmental factors have also not been studied. More large-scale human studies are needed – and those studies are extremely expensive.

In the meantime, John Cryan, a professor of anatomy and neuroscience at University College Cork, encourages people to eat a diet high in fiber, prebiotics and fermented foods. A study by Cryan and his colleagues found that diet

Cryan and his colleagues studies 45 people eating that diet and found they were less stressed than the control group.

“What I like about fermented foods is that they democratize the science,” says Cryan. “They don’t really cost much and you don’t have to get them from some fancy store. You can do it yourself. In this field, we want to provide mental health solutions to people from all socioeconomic areas.”

Read more (BBC)

- Published in Science

Better Bread: Study Proves Sourdough Wins

Plenty of anecdotal evidence lauds sourdough as the healthier bread alternative for those with wheat or gluten intolerance, but there is little research providing data on the topic. Now new research proves the longer a sourdough ferments, the better the bread.

Sourdough is a fermented bread fortified with dietary fibers, increased mineral bioavailability, lower glycemic index and improved protein digestibility compared to its unfermented counterparts. And, as more people shun traditional bread because of a wheat or gluten intolerance, sourdough is increasing in popularity.

Researchers at the University of Minnesota are studying the effects of dough fermentation and wheat varieties to create a bread that’s easier to digest. They found the longer fermentation time makes a more digestible bread. The results, published in November in the Journal of Cereal Science, found a 12 hour ferment versus a four hour ferment dramatically reduces the short-chain carbohydrates that aren’t absorbed properly in the gut.

“Wheat sensitivity seems to be getting worse,” says James Anderson (pictured, left), professor and wheat breeder at the University of Minnesota and one of the study authors. “The motivation for me as a wheat breeder to get involved in this research is the wheat sensitivity issue.”

Those short-chain carbs – FODMAPs (fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides and polyols) and ATIs (amylase/trypsin-inhibitors) – are what causes digestive problems in some people.

“There is evidence to document that sourdough processing or fermentation in general is able to reduce these FODMAPs and ATIs,” said George Annor (pictured, right), a professor of cereal chemistry and technology at the University of Minnesota and another of the study’s authors.

While fermentation time makes a difference in digestibility of sourdough, so do wheat varieties. Ancient grains such as Einkorn and Emmer performed well, same with the modern Linkert variety.

Though the study proves sourdough and other slow-rising breads can help those who are sensitive to wheat, the modern baking industry is dominated by sped up processing techniques. Like most commercial breads, frozen pizza crust and other convenience foods. Annor says he wants “them to keep those processes as much as they can,” but using a better wheat variety will aid digestibility.

“There’s more that we don’t know about fermentation than we do know, and it’s a wonderfully complex world,” says Brian LaPlante, a fellow Minnesotan and owner of Back When Foods.

LaPlante and his wife began making their own sourdough with ancient grains from his brother’s farm when LaPlante’s son began experiencing digestive problems. By incorporating sourdough and other fermented foods into his diet, his son’s health dramatically improved. LaPlante started his business Back When Foods that develops slow food with less processing – and hooked up with Anderson and Annor to help with their research. LaPlante provided the dough samples of varying ferment times that the UofM analyzed for their study.

“When you have fermented food in your diet, it has a profound impact on your microbiome,” he adds. “And I think that will be the trend, is food will become your medicine again.”

Gut Microbes Key to Exercise Motivation

A new study published in Nature reveals some new insight into the gut-to-brain pathway. Certain bacteria types boost our desire to exercise.

The study, performed on mice by researchers at the University of Pennsylvania, found differences in running performance based on the presence of gut bacterial species Eubacterium rectale and Coprococcus eutactus in the higher-performing mice. The metabolites known as fatty acid amides that the bacteria produce stimulate the sensory nerves in the gut, enhancing activity in the motivation-controlling region of the brain.

“If we can confirm the presence of a similar pathway in humans, it could offer an effective way to boost people’s levels of exercise to improve public health generally,” says Christoph Thaiss, PhD, an assistant professor of microbiology at Penn Medicine and a senior study author.

Researchers were surprised to find genetics accounted for only a small portion of performance differences in the mice. Gut bacterial populations were “substantially more important,” reads the study. Giving the mice antibiotics to get rid of their gut bacteria reduced the mice’s running performance by half.

“This gut-to-brain motivation pathway might have evolved to connect nutrient availability and the state of the gut bacterial population to the readiness to engage in prolonged physical activity,” says J. Nicholas Betley, PhD, an associate professor of Biology at the University of Pennsylvania’s School of Arts and Sciences and a study author. “This line of research could develop into a whole new branch of exercise physiology.”

Read more (Science Daily)

Fermenting Sustainable Food

The food industry is at the center of multiple bottlenecks hurting food production – global food crisis, extreme weather, supply chain disruption, inflation and geopolitical conflict. Researchers at Singapore’s prestigious Nanyang Technological University (NTU) have found a sustainable food solution: fermentation.

An article in New Food Magazine details the fermentation innovations of NTU and how they’re fermenting the edible by-products of food manufacturing to produce new food. Their food studies found great promise in okara (the “insoluble remains of soybeans from the production of soy milk and beancurd”) and spent grain (the “residual barley pulp from the beer industry”).

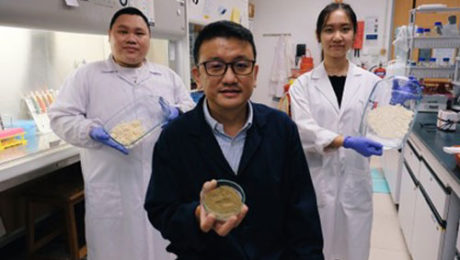

“Fermentation is a way to repurpose okara, a major food manufacturing side stream that is often discarded, and transform it into a highly nutritious food,” says Dr. Ken Lee (pictured), senior lecturer at NTU’s School of Chemistry, Chemical Engineering and Biotechnology, who led a study published in LWT – Food Science and Technology.

The study showed okara fermented with a mixed culture of the fungus Aspergillus oryzae and the bacterium Bacillus subtilis made a nutritional-rich food. This inoculated fermentation process is also used to make soy sauce.

Fermenting spent grain also makes a nutrient-rich, upcycled food: a protein-rich food emulsifier. A separate study by NTU researchers published in Food Chemistry found that plant-based food can replace dairy and eggs in condiments like mayonnaise, dressings and whipped cream.

“Upcycling food waste such as spent grain for human consumption is an opportunity for enhancing processing efficiency in the food supply chain, as well as potentially promoting a healthier plant-based protein alternative to enrich diets,” says Professor William Chen, professor and director of NTU’s Food Science and Technology Programme.

Read more (New Food Magazine)

- Published in Science

Promoting Korean Fermented Foods

Korean ferments are gaining popularity amongst U.S. consumers, and Korean agriculture leaders are trying to increase exports of Korean-made fermented foods to the U.S. At the first Korean Fermented Food Forum this month in Washington D.C., industry leaders shared their expertise on the future of Korean ferments in the American market.

“If you’re going to look at and work with fermented foods, you really have to look at Korea because that’s where all the action is, that’s where all the good food is,” says Fred Breidt, PhD, microbiologist with the USDA (and a TFA Science Advisor). Breidt was the keynote speaker at the event. “It’s becoming more and more popular to use these kinds of foods for their tremendous flavors that they can impart to food products and their health benefits as well.”

The forum was sponsored by Korea’s Ministry of Agriculture and the Korea Agro-Fisheries & Food Trade Corporation (aT Corporation). It coincided with celebrations earlier that week for November 11 being designated as Kimchi Day being in Washington D.C. and Virginia. They join New York and California, which ratified Kimchi Day in the respective states in 2021. The aT Corporation is actively leading efforts for all U.S. states to designate a Kimchi Day.

“With the growing global popularity of Korean food, I am delighted and eager to promote awareness and educate consumers on the health benefits of kimchi and Korean fermented food products, such as kimchi, fermented soybeans, salted seafood and vinegar,” says Choon Jin Kim, president of the aT Corporation. He called kimchi “Korea’s staple fermented soul food. I believe the reason that Americans enjoy kimchi so much is that the many qualities of Korean fermented foods, such as its excellent nutritional value, health benefits and taste, are beginning to shine.”

Major Growth

Sales of Korean fermented foods are growing exponentially in the U.S. According to U.S. retail sales figures tracked by The Fermentation Association and SPINS data, kimchi increased in sales by 22% in 2022, totaling $37.56 million in sales. Sales of gochujang grew 8% in 2022, totaling $6.57 million in sales.

“It’s a wave that’s been coming for a long time,” said Rob Rubba, executive chef and partner at Oyster Oyster restaurant in D.C. “Where someone who was previously omnivore like myself, who is seeking depth of flavor in something you might not associate with a vegetable, you can achieve that through fermented foods.”

When asked why fermentation grew so much during the Covid-19 pandemic, Amelia Nielson-Stowell, TFA’s editor, says fermentation touches multiple global food movements. Fermented foods are healthy, natural, green, innovative, artisanal, flavorful and functional.

“Fermentation is not a trend, it’s the oldest food craft, it’s a traditional food art with history in every culture around the world and it’s absolutely having a resurgence here in the U.S.,” Nielsen-Stowell says.

She points out that, while kimchi grew 22% in sales this year, it’s increased market size to 16% of the fermented vegetables category. In 2021, kimchi sales grew 90%, but were only 7% of the fermented vegetables category.

“More brands tuned into kimchi’s popularity, so we’re seeing more market saturation,” Nielsen-Stowell says. “There’s huge opportunities for more Korean fermented foods here in the U.S.”

Kheedim Oh attribute’s part of kimchi’s success to Korean agricultural leaders. Oh, the chief minister of New York-based brand Mama O’s Premium Kimchi, says “We have to give credit to the Korean government and groups like the aT because the Korean government recognizes the soft power of promoting.”

When he began Mama O’s 20 years ago, there were few American-made kimchi companies. Now, “there’s like a new kimchi company everyday. I don’t think it’s going to stop because kimchi is the best food ever, it goes with everything.”

Julie Sproesser agrees. Sproesser, the Interim Executive Director of Restaurant Association Metropolitan Washington, says she’s seen Korean ingredients and Korean hybrid restaurants across the D.C., Maryland and Virginia areas increase in the last seven years.

“It seems like it’s not an accident and not going anywhere,” she adds.

Today’s Science

During his presentation, Breidt shared an overview on Korean fermented foods, including kimchi, gochujang, ssamjang and doenjang.

Kimchi’s origin begins 11,000 years ago to the start of one of the world’s “first technologies invented” – pottery. Koreans discovered adding veggies with salt and water could preserve food during a time there was no refrigeration.

Scientists are continuing to learn about the significant health benefits of the probiotic-rich, lactic acid bacteria in fermented foods. Breidt says kimchi is especially beneficial because it has 10 million to 1 billion live lactic acid bacteria per gram. Through emerging genomic tools, science is now linking specific lactic acid bacteria strains in fermented foods to health benefits.

There are challenges to selling in the U.S. market, though. Briedt says many Americans like a lightly-fermented kimchi (with a pH in the high 3’s or low 4’s), but once fermentation has begun, it’s hard to stop unless it is refrigerated.

“It’s difficult to get lightly-fermented kimchi that’s imported from somewhere else. You pretty much have to get it locally or near the source of where it’s being produced,” he says, noting because kimchi is a live, fermented product, it doesn’t travel well. “The flavors will change over time, and the evolution of these microbial communities is going to proceed unless you somehow sterilize the product, which is really counter to the whole idea of what excites people about kimchi.”

The environmental factors around fermented vegetables must be meticulously monitored to produce a consistent product. Like the freshness of the ingredients, the correct size of the fermentation vessel, the cut of cabbage and the proper sterilization of cutting machines.

“Having access to high-quality products here I think is really boosting this, and it’s going to keep going as long as we continue those efforts,” Breidt adds.

The 2022 Korean Fermented Food Forum was the first, though it is expected to recur annually, coinciding with Kimchi Day. Jeanie Chang was the moderator of the forum, a licensed clinician who uses Korean dramas as a way to explore mental health through her Instagram, Noona’s Noonchi.

Microbes in Cheese

Do you love a mild mozzarella, a salty Parmesan or a funky brie? Thank microbes.

Though the thousands of varieties of the world’s cheeses all begin as a white lump of curd, the diversity is astounding. From the flavor to the color to the texture, cheese goes from “uniform blandness to this cornucopia” thanks to bacteria, yeasts and molds. An article in Smithsonian Magazine – titled The Science Behind Your Cheese – shares the details.

“More than 100 different microbial species can easily be found in a single cheese type,” says Baltasar Mayo, a senior researcher at the Dairy Research Institute of Asturias in Spain.

Scientists have only recently begun to study the microbial nature of cheese. To find out the bacteria and cheese present, scientists extract DNA from the cheese, then match it to genes in the database.

“The way we do that is sort of like microbial CSI, you know, when they go out to a crime scene investigation, but in this case we are looking at what microbes are there,” says Ben Wolfe, a microbial ecologist at Tufts University.

Though cheesemakers often add starter cultures of beneficial bacteria to fresh curds to transform it into a delicious cheese, Wolfe’s team found the microbiomes of the cheese “showed only a passing resemblance to those cultures. Often, more than half of the bacteria present were microbial ‘strangers’ that had not been in the starter culture,” continues the article.

Those “strangers” dumbfounded researchers. Microbes like Brachybacterium found in Gruyère are more commonly found in soil, seawater and chicken litter. Or the Halomonas most commonly found in salt ponds and marine environments. Or, Brevibacterium linens found in damp areas of skin, such as between the toes. Those bacteria come from the environment of the cheesemaking facilities. The microbes come from the cow, goat or sheep, the bacteria in the farm’s stable, the skin bacteria from the hand of the milker, the microbes in the dairy storage tank and/or the sea salt in the brine used to wash down the cheese. Hundreds of bacteria have been detected in long-ripened cheeses.

“Furthermore, by repeatedly testing, scientists have observed that there can be a sequence of microbial settlements whose rise and fall can rival that of empires,” continues the article.

Modern cheesemaking is, sadly, more controlled, meaning modern cheese isn’t as flavorful. Cheesemaking has “become tamer over time,” cleaner and more sterilized, filtered, pasteurized, machine operated.

“Many of our cheddars, provolones and Camemberts, once wildly proliferating microbial meadows, have become more like manicured lawns. And because every microbe contributes its own signature mix of chemical compounds to a cheese, less diversity also means less flavor — a big loss.”

Read more (Smithsonian Magazine)

- Published in Food & Flavor, Science

The Microbes We Should (or Shouldn’t) Be Eating

How important are microbes in the human diet? And does it matter which ones we eat?

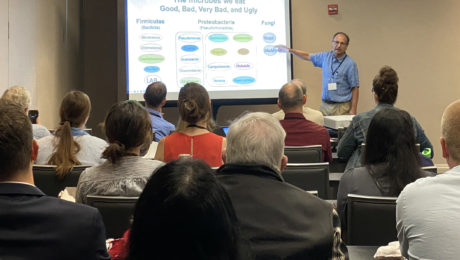

“Maybe we’re not too far from proving the following; the dietary guidelines, the My Plate guidelines, should include fermented foods, including those that contain live microorganisms, as part of a healthy diet,” says Bob Hutkins, PhD, a professor at the University of Nebraska (and TFA Advisory Board member). Hutkins explored this hypothesis during his standing-room only presentation at FERMENTATION 2022 titled The Microbes We Should (or Shouldn’t) Be Eating.

He estimates, just like the daily fiber recommendations were granted based primarily on epidemiological studies, fermented foods are going through the same process. And one day there may be a daily fermented food recommendation.

Why Should We Be Eating Live Microbes?

Highly processed foods, prolific use of antibiotics, and overly hygienic environments have resulted in significantly less exposure to microbes. This includes those microbes that help to maintain a healthy gut microbiome and that keep our immune system functioning properly. Indeed, according to the so-called Old Friend’s Hypothesis, exposure to microbes is necessary for proper development of the immune system. This is especially true for Western countries. One highly-cited study published in Lancet found Inflammatory Bowel Diseases (IBDs) like Crohn’s Disease and Ulcerative Colitis — “are predominantly associated with Western populations. You rarely see these diseases in other parts of the world,” Hutkins says.

“In the Covid era, we have certainly learned that preventing infectious diseases remains a major challenge, and being a bit germophobic is understandable. Certainly, modern food technology that includes pasteurization has significantly reduced pathogen risk, improved food safety, enhanced shelf life, and reduced food waste. Nonetheless, our environment has often become too clean, too hygienic and we are no longer exposed to microbes,” he adds.

Another study based on research in Finland found the Old Friend’s Hypothesis holds true for development of allergies, asthma, and eczema. As the authors noted “changes in environment and lifestyle, affecting microbial exposure and immune regulation, seem to play a major role in the so-called post-war allergy epidemic”. Indeed, in a 2002 editorial in the New England Journal of Medicine, three “old-school” lifestyle approaches were mentioned for protecting against the development of allergies: supplementing with lactobacillus (the bacteria found in fermented foods), owning a dog in your home and attending daycare.

Consuming Live Microbes Benefits Human Health

To address this situation, Hutkins and other food scientists are proposing adding fermented foods to the Recommended Dietary Guidelines, along with the daily dose of nutrients and vitamins.

“One of the main challenges however, will be to distinguish between nutrients and microbes,” Hutkins says.

The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) has explored this further. A panel of ISAPP microbiologists, nutritionists, doctors and statisticians (including Hutkins) used the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) to deep dive into the American diet. The NHANES database catalogs what adults and children are eating, then collects health indicators for associated diseases.

ISAPP researched the estimated live microbes in foods to find sufficient evidence that a live dietary microbe intake should be a part of a dietary recommendation. It was a big undertaking, since there are 9,388 foods inNHANES. ISAPP ranked each food’s microbial count. They found microbial count was low for processed, heat-processed foods, medium level for fresh fruit and vegetables and high for fermented foods, like fermented dairy (yogurt, fresh cheese) and fermented vegetables.

“Ninety-six percent of the foods we eat are in the low” count for microbes, he said. “Hardly any were in the fermented category, around one percent.”

Still, not all live microbes are the same. The microbes considered healthy – lactic acid bacteria and bifidobacteria – are only dominant in fermented foods. Most of the live microbes consumed in the average diet are proteobacteria from fresh fruits and vegetables.

The Institute for the Advancement of Food and Nutrition Sciences, which catalogs nutrition labels for all USDA food data, now has a space for a brand to enter the amount of live microbes in their product. There’s a dropdown menu to add genus and species of a probiotic strain, too.

“This new effort is a way to introduce the live microbes in the database,” Hutkins says, noting a company would have to enter it voluntarily. “They’re offering a noncompetitive, objective, transparent mechanism for stakeholders to understand live microbe intake and eventually link intake to health outcomes.”