Fermenting Sustainable Food

The food industry is at the center of multiple bottlenecks hurting food production – global food crisis, extreme weather, supply chain disruption, inflation and geopolitical conflict. Researchers at Singapore’s prestigious Nanyang Technological University (NTU) have found a sustainable food solution: fermentation.

An article in New Food Magazine details the fermentation innovations of NTU and how they’re fermenting the edible by-products of food manufacturing to produce new food. Their food studies found great promise in okara (the “insoluble remains of soybeans from the production of soy milk and beancurd”) and spent grain (the “residual barley pulp from the beer industry”).

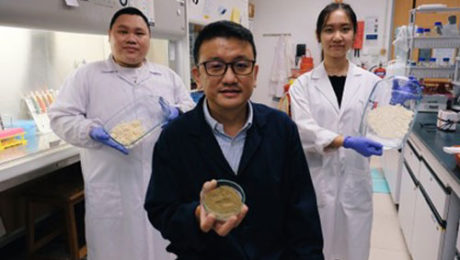

“Fermentation is a way to repurpose okara, a major food manufacturing side stream that is often discarded, and transform it into a highly nutritious food,” says Dr. Ken Lee (pictured), senior lecturer at NTU’s School of Chemistry, Chemical Engineering and Biotechnology, who led a study published in LWT – Food Science and Technology.

The study showed okara fermented with a mixed culture of the fungus Aspergillus oryzae and the bacterium Bacillus subtilis made a nutritional-rich food. This inoculated fermentation process is also used to make soy sauce.

Fermenting spent grain also makes a nutrient-rich, upcycled food: a protein-rich food emulsifier. A separate study by NTU researchers published in Food Chemistry found that plant-based food can replace dairy and eggs in condiments like mayonnaise, dressings and whipped cream.

“Upcycling food waste such as spent grain for human consumption is an opportunity for enhancing processing efficiency in the food supply chain, as well as potentially promoting a healthier plant-based protein alternative to enrich diets,” says Professor William Chen, professor and director of NTU’s Food Science and Technology Programme.

Read more (New Food Magazine)

- Published in Science

“Dairy is Ripe for Innovation”

As the dairy industry continues to suffer from low sales, could fermentation help the industry meet changing consumer needs? Functional dairy products (like fermented dairy) and animal-free precision fermentation products are major consumer trends for the dairy industry to adapt.

Functional dairy products are “ripe for expansion,” said Brad Schwan, vice president of Archer-Daniels-Midland Company, said brands have to invest in alt protein technologies to feed the future tech-savvy generation. Fermented dairy – like yogurt, kefir and fresh cheese – are all functional dairy.Fifty-eight percent of global consumers perceive a connection between gut function and other aspects of well-being. Consumers are looking for dairy with simple ingredient lists.

“The gut microbiome is a key growth area for functional, tailored offerings, as more consumers are making the link between their gut, digestive health and overall well-being,” Schwan added.

Consumers are looking for dairy with simple ingredient lists. They want their dairy to support pre- and post-workout goals, energy solutions, hydration, digestive support and immune function.

More consumers are embracing a mix of an animal- and plant-based diet. Fifty-two percent of consumers eat a flexitarian diet now.

Alt protein – once seen as a fringe biotechnology – is becoming more mainstream. Brad Schwan, vice president of Archer-Daniels-Midland Company, said brands have to invest in alt protein technologies to feed the future tech-savvy generation.

“While consumer acceptance of alternative solutions beyond plant proteins is still building, we foresee digital-natives Gen Z and Gen Alpha leading the way in the growing acceptance of novel methods and technologies,” he said in a report on global food trends. “Additionally, the dairy industry is ripe for more innovation in the coming year, through leveraging both new technologies…As consumers grow more accustomed to seeing novel proteins from unexpected places, the alternative dairy arena will flourish with new possibilities.”

Read more (Dairy Reporter)

- Published in Business

Bean-free Chocolate & Coffee

The front page of the Financial Times featured a new wave of alternative foods: chocolate and coffee, but without the beans.

Cultivating both cocoa beans for chocolate and coffee cherries for coffee at such a high rate for global consumption is damaging to the environment. It’s linked to deforestation. The working conditions for many of the farmers are also deplorable, with child and slave labor and poor wages. Now multiple startups are trying to make a market for bean-free products.

“You realise that a lot of our favourite foods, whether it’s beef burgers or a cult of coffee or a chocolate bar, there’s so much damage,” said Johnny Drain, chief technology officer of WNWN Food Labs, a London-based maker of cocoa-free chocolate. “Not just to the climate but to the people, typically in developing countries who are producing those products for us.”

Drain is a fermentation expert who formerly worked with restaurants to make unique flavor profiles using fermentation. He’s founded WNWN with Ahrum Pak, a former financier now working in the foodtech space with Drain (both pictured). Their chocolate is made from fermented barley and carob.

More startups are, too, trying to be a solution to an unhealthy chocolate and coffee industry. In Munich, Planet A developed a cocoa-free chocolate which has chief ingredients of fermented oats and sugar beet. They call it “Nocoa.” In the U.S., Voyage Foods and California Culture make chocolate from lab-grown cocoa.

Bean-free coffee, meanwhile, has been created by two U.S. startups – Atomo in Seattle uses date seeds, chicory root, grape skin and green tea to create a canned cold brew coffee. Compound Foods in San Francisco. The latter is recreating coffee using synthetic biology and fermentation.

“We want to give consumers a choice,” said Andy Kleitsch, co-founder of Atomo, who added that although they had been worried that “the coffee industry would hate us or that the baristas might hate us, the reception has been positive”.

Many of these entrepreneurs note alt products are not the only solution to an environmentally-damaging food industry. Drain adds: “It’s just one additional way of trying to change an industry that is built on inequity and slave labour.”

Read more (Financial Times)

- Published in Business, Food & Flavor

Fermentation for Global Health

Though scientists and environmentalists have warned about the dangers of increased meat consumption, Americans’ appetite for it is not slowing down. The last three years marked the largest amount of meat produced on record.

“People know about the harms of industrial agriculture, but people eat more and more and more meat,” says Bruce Friedrich, CEO of the Good Food Institute (GFI). “It’s an inextricable rise despite more and more attention to the issues. The vast majority of people are just not going to apply ethical considerations to their food choices.”

Fermentation, Friedrich declares, can be part of the solution. “Fermentation can be so powerful for global health, climate and biodiversity,” he says.

Friedrich spoke at FERMENTATION 2022 on alternative protein innovation. GFI, a nonprofit, aims to accelerate the innovation of fermented, plant- and cell-based alternative meat. But the young, rapidly-growing alt protein industry faces major obstacles in scaling, regulation, pricing and consumer acceptance. Friedrich told a room of professional fermenters at the conference to consider shifting to a career in alternative proteins.

“Anyone involved in fermentation, you have the expertise in knowledge. It’s cross-applying the skills and interest in your professional life into this new field,” he says. “One of the significant barriers for all the companies doing this is talent, which is to say – you.”

Global Agriculture Crisis

Friedrich does not mince his words: we’re on the precipice of a major environmental and health crisis if we don’t reduce meat consumption.

Mass producing meat is “extraordinarily inefficient.” Huge amounts of crops are grown to feed livestock so humans can then eat the animals.. “We have been using an antiquated method to produce meat for 12,000 years,” Friedrich adds.

Internationally, 4 billion hectares of land are used for agriculture – 3 billion are for grazing livestock or to grow their food. It takes 9 calories of feed to produce 1 calorie of chicken; 40 calories to produce 1 calorie of beef.

“This is an incredibly inefficient way to try and feed the world,” Friedrich says.

And it’s getting worse. By 2050, global meat consumption is projected to increase – conservative estimates say 50%, while others go as high as 260%.

Animal agriculture also is thought to be a major contributor to global climate change and a major factor in deforestation. Livestock are pumped with antibiotics, creating resistance in humans that consume that meat.

Future of “Meat”

The answer isn’t necessarily a world of vegetarians – it’s to change traditional meat.

Friedrich compares the situation to renewable energy and electric vehicles. For decades, government leaders have preached reducing fossil fuel consumption. But, as populations have risen, so has energy consumption.

“You are not going to convince people to consume less energy,” he says. “What you need to do is replace fossil fuels with renewable energy.”

Similarly with meat, there cannot be a meatless world. “This is innovation focused, it is not about behavior change,” he says.

“GFI when we started, we were talking about disrupting animal agriculture. We very quickly realized our hope is to transform industrial animal agriculture,” he says. “Things will happen a lot more quickly if we have the major corporations on board.”

GFI is “enthusiastically working with the biggest companies in the world:” JBS, Tyson, Smithfield, Cargill and BRF, the five largest global meat producers.

The aim is not to regulate big agriculture or stop subsidies. GFI hopes to open access into the science behind alternative proteins, incentivize the private sector to continue R&D and encourage government funding.

“The same sort of cash breaks that allowed Tesla to be successful should apply to Nature’s Fynd and Impossible Foods and others if they want that money,” Friedrich says, listing two major companies in the alternative protein industry. “Our global battle cry is that governments should be funding alternative proteins.”

Food Trifecta

By not gatekeeping alt protein technology, Friedrich says GFI is helping perfect the process of giving consumers the exact same meat experience, but using plant- or cell-based meats. People want the food trifecta, Friedrich says: Is it delicious? Does it fill me up? Is it reasonably priced?

Fermentation is a booming sector in the alternative protein industry. It is split into three categories: traditional fermentation using lactic acid bacteria, yeasts or fungi; biomass fermentation which involves naturally occurring, protein-dense, fast-growing microorganisms; and precision fermentation, which uses microbial hosts as “cell factories” to produce specific ingredients.

Data from GFI found, of the alt protein startups utilizing fermentation, 45% use precision fermentation, 41% use biomass fermentation and the remaining 14% use traditional fermentation.

GFI recently hired two fermentation scientists, and their studies are already suggesting biomass and traditional fermentation will have better environmental numbers than plant-based meats. Fermentation is also a more powerful process than plant-based meat applications because fermentation can replicate precise fermentation proteins. And although traditional fermentation is the smallest part of the fermented alternative protein category, GFI sees it growing because of its ability to produce appealing flavors..

“Traditional fermentation can be an absolutely essential element to get meat to taste the same or better or cost the same or less,” he says.

“The plant based and fermentation products, they’re just getting started. The idea of competing with industrial animal meat has been around for (snaps his fingers) that long. The products are just going to improve and improve and improve.”

Jason White Leaves Noma Amidst Its “Biggest Transformation”

Jason White has resigned as director of fermentation for Noma. He will be CEO and co-founder of a yet-to-be-announced biotechnology company in the United States. White tells The Fermentation Association that he will share details of his new project in the coming weeks.

Regarded as one of the best restaurants in the world, Noma earned their third Michelin star last year.

This summer, Noma owner Rene Redzepi announced that 2023 – the 20th anniversary of Noma – will be “our final year with Noma as we know it.”

“We have a plan, and I can’t wait to share more with you later this year, but for now, know that big changes are happening,” Redzepi wrote on Instagram, adding it’s “our biggest transformation so far…We’ve been laying some new foundational stones so we can continue to grow as an organization for the next 20 years.”

The staff had planned to take off this fall to travel to an undisclosed (but rumored to be in Mérida, Mexico) international location to learn some new cooking techniques and open a pop-up restaurant. But both the travel and pop-up have been postponed until spring 2023 due to ongoing travel restrictions related to the Covid-19 pandemic.

Last year Noma launched Noma Projects, a direct-to-consumer product line aimed at generating more revenue for the restaurant. In June, Bloomberg reported the restaurant was unprofitable in 2021 – the first time in four years – losing 1.69 million krone (~$225,000) after recording a small profit the prior year. Noma also received 10.9 million krone (~$1.45 million) from the Danish government in Covid-19 relief.

Noma’s previous head of the fermentation lab, David Zilber, also left the restaurant for a job in the biotech industry. He is a food scientist at Chr. Hansen.

White, who spoke at the 2nd international Food Innovation Conference this summer (produced by the Gottlieb Duttweiler Institute (GDI)), said fermentation is motivating scientists to listen to gastronomers.

“There’s going to be a huge exchange in this two-way road that we’re living in. Innovation in flavor coming from gastronomy and innovation coming from a high-level biotechnology, they are going to be harmonious,” White said. “We’re going to be able to create this infrastructure and community of people who have the same goal, and the same goal is going to be the wellness of our planet.”

- Published in Business

Chicago: A Fermentation Hub

If you still think of hot dogs and deep dish pizza as the icons of Chicago’s culinary scene, you need to think again. The so-called Capital of the Midwest is a hub of innovation in the food industry. Chicago has the largest food and beverage production in the U.S., with an annual output of $9.4 billion. Food startup companies in the region raised $723 million in venture capital last year.

“Chicago is one of the most diverse cities for eating,” says Anna Desai, Chicago-based influencer of Would You Like Something to Eat on Instagram. ”Our culinary scene is constantly elevating and evolving. We are always just a neighborhood or tollway away from experiencing a new culture and cuisine. I’m most excited when I find an under-the-radar spot or discover a maker who can pair flavors and ingredients that get you curious and wanting more.”

Desai started her blog in part because she wanted to champion the Asian American and Pacific Islanders (AAPI) community in the Chicago food and beverage scene. “Food has long served as a cultural crossroad,” she adds, and Chicago’s multicultural cuisine exemplifies that sentiment.

Chicago is home to some of the most creative minds in fermentation, from celebrity chefs, zero waste ventures, alternative protein corporations and the world’s largest commercial kefir producer. There are dozens of regional and artisanal producers lacto-fermenting vegetables, brewing kombucha and experimenting with microbes in food and drink.

“Chicago is a great food city in its own right, so naturally there is a ton of talent in the fermentation space,” says Sam Smithson, chef and culinary director of CultureBox, a Chicago-based fermentation subscription box. “The pandemic’s effect on restaurants has also spawned a new wave of fermenters (ourselves included) that are looking for a path outside the grueling and uncertain restaurant structure to display our creative efforts. This new wave is undoubtedly community-motivated and concerned more with mutual aid than competition. There is a general feeling that we are all working towards the same goal so cooperation and collaboration is soaring and we are seeing incredible food come from that.”

Flavor is King

Flavor development is still the prime motivation for chefs to experiment with fermentation. A good example is at Heritage Restaurant and Caviar Bar in Chicago’s Humboldt Park neighborhood.

“Fermentation has been a cornerstone of the restaurant since its inception,” says Tiffany Meikle, co-owner of Heritage with her husband, Guy. “With the diverse cuisines we pull from, both from Eastern and Central Europe and East Asia, we researched fermentation methodologies and histories, and started to ‘connect the dots’ of each culture’s fermentation and pickling backgrounds.”

Menus have included sourdough dark Russian rye bread, toasted caraway sauerkraut, kimchi made from apples, Korean pears and beets and a kimchi using pickled ramps (wild onions). Heritage has also expanded their fermentation program to the bar, where they’ve created homemade kombucha, roasted pineapple tepache, sweet pickled fruits for cocktail garnishes, and kimchi-infused bloody mary mix.

“It’s fascinating to me that there are so many ingredients you can use in a fermented product,” says Claire Ridge, co-founder of Luna Bay Booch, a Chicago-based alcoholic kombucha producer. “People are really experimenting with interesting ingredients in kombucha…I have seen brewers do some of the wildest recipes and some recipes that are very basic.”

Innovating Food

Chicago-based Lifeway Kefir is indicative of the innovation taking place in the city. Last year the company expanded into a new space: oat-based fermentation, launching a dairy-free, cultured oat milk with live and active probiotics.

“We’ve spent so many years laying the groundwork in fermented dairy,” says Julie Smolyansky, CEO. “Now we’re experimenting and expanding to see what’s over the next horizon, though we’ll always have kefir as our first love.”

Chicago is home for two inventive fermented alternative protein startups: Nature’s Fynd and Hyfé Foods. Both companies were born out of the desire to create alt foods without damaging the environmental.

“Conscious consumerism is a trend that’s driving many people to try alternative proteins, and it’s not hard to understand why,” says Debbie Yaver, chief scientific officer at Nature’s Fynd. The company uses fermentation technology to grow Fy, a nutritional fungi protein. “Fungi as a source of protein offer a shortcut through the food chain because they don’t require the acres of land or water needed to support plant growth or animal grazing, making fungi-based protein more efficient to produce than other options.”

Alternative foods outlasting the typical trend cycle is a challenge for companies like Nature’s Fynd. When grown at scale, Fy uses 99% less land, 99% less water and emits 94% fewer greenhouse gasses than raising beef. But, to make an impact, “we need more than just vegans and vegetarians to make changes in their diets,” Yaver adds.

Waste Not

Numerous companies are using fermentation as a means to eliminate waste. Hyfé Foods, another player in the alternative protein space, repurposes sugar water from food production to create a low-carb, protein-rich flour. Fermentation turns a waste product into mycelium flour, mycelium being the root network – or hyphae (hence the company name) — of mushrooms.

“[We’re] diverting input to the landfill and reducing greenhouse gas emissions at scale,” says Michelle Ruiz, founder. “Hyfé operates at the intersection of climate and health, enabling regional production of low cost, alternative protein that reduces carbon emissions and is decoupled from agriculture.”

Symmetry Wood is another Chicago upcycler. They convert SCOBY from kombucha into a material, Pyrus, that resembles exotic wood. Founder Gabe Tavas says Pyrus has been used to produce guitar picks, jewelry and veneers. Symmetry uses the discarded SCOBY from local kombucha brand Kombuchade.

Many area restaurants and culinary brands also use fermentation to preserve food for the long Chicago winters, when local produce isn’t available. Pop-up restaurant Andare, for example, incorporates fermentation into classic Italian dishes.

“Finding ways to utilize what would otherwise be waste products inspired our initial dive into fermentation. The goal is not just to use what’s leftover, but to make it into something delicious and unique,” says Mo Scariano, Andare’s CEO. “One of our first dishes employing koji fermentation was a summer squash stuffed cappellacci served with a butter sauce made from carrot juice fermented with arborio rice koji. Living in a place with a short grow season, preservation through fermentation allowed us access throughout the year to ingredients we only have fresh for a few weeks during the summer.”

Industry Challenges

Despite growing interest and increasing sales, fermenters face some significant hurdles.

Smithson at CultureBox says he sees that consumers are open to unorthodox, less traditional ferments. Though favorites like kombucha and sauerkraut dominate the market, “their share is being encroached on by increasingly more varied and niche ferments.” But getting these products to market can be a challenge. Small-scale, culinary producers are challenged by the regulatory hoops they need to jump through to legally sell ferments – especially unusual ones a food inspector doesn’t recognize.

“The added layer of city regulations on top of state requirements, sluggish health department responses, and inflexible policy chill the potential of small producers,” Smithson says. But he highlights the recently-passed Home-to-Market Act of Illinois as positive legislation helping startup fermenters.

Consumer awareness and education are also vital. “Many longstanding and harmful misconceptions on the safety and value of fermented products still exist,” Smithson says.

Matt Lancor, founder and CEO of Kombuchade makes consumer education a core part of marketing, to align kombucha as a recovery drink.

“Most mainstream kombuchas are marketed towards the yoga/crystal/candle crowd, and I saw a major opportunity to create and market a product for the mainstream athletic community,” he says. “We’re on a mission to educate athletes and the general public about these newly discovered organs [the gut] – our second brain – and fuel the next generation of American athletes with thirst quenching, probiotic rich beverages.”

Product packaging provides much of a consumer’s education. Jack Joseph, founder and CEO of Komunity Kombucha, says simplicity is key.

“People are more conscious of their health now, more than ever before,” he says. “So now it comes down to the education of the product and creating something that is transparent and easy for the consumer to digest.”

Sebastian Vargo of Chicago-based Vargo Brother Ferments agrees.

“Oftentimes food is considered ‘safe’ due to lack of microbes and how sterile it is,” he says. “Fermentation eschews the traditional sense of what makes food ‘safe’. We need to create a set standardized guide for fermented food to follow, and change our view of living foods in general. One of the brightest spots to me is the fact that fermentation is really hitting its stride and finding its place in the modern world, and I don’t see it going anywhere but up in the near future.”

- Published in Business, Food & Flavor

Bubbling Over: Chicago Fermentation Scene

In anticipation for our conference FERMENTATION 2022 in Chicago, TFA asked over a dozen area fermenters about what they love about the city’s fermentation scene. Their answers touched on a number of points: creativity in foods and beverages, diverse offerings, scrappy and determined founders, supportive community and evolving foodscape.

Below are the answers from three local fermentation experts – kefir company founder Julie Smolyansky (Lifeway Kefir), local ferments producer Sebastian Vargo (Vargo Brother Ferments) and chief scientific officer Debbie Yaver, PhD (Nature’s Fynd).

The question: What do you love about the Chicago fermentation scene?

Julie Smolyansky, Lifeway Kefir

Chicago is a true melting pot. We have diversity, talent, and lots of skilled manufacturing talent. It’s one of the premier food cities in the world and I’m so grateful that we’ve been able to build our business and community in Chicago. The natural foods, fermentation, and dining scene all commingle to create opportunities for a special type of risk-taking that’s uniquely Chicago. Lots of it bubbles under the radar – who would have guessed that the kefir capital of the United States is in the Midwest?

Sebastian Vargo, Vargo Brother Ferments

I love the fact that we are seeing more fermentation than ever, from restaurants to store shelves to folks starting projects at home. I love the community behind it, folks are sharing recipes and exchanging tips and tricks. People don’t have time for gatekeeping anymore.

Debbie Yaver, Nature’s Fynd

I love that it flips the script. For so long Chicago was known as the “Hog Butcher to the World,” but now one of the oldest technologies in the books is experiencing a renaissance. There are lots of companies utilizing traditional fermentation, but not as many in the food space. It’s exciting to be one of the newer kids on the block, to see how different companies are putting fermentation to work, and to get to pull from such a stocked talent pool. Chicago is full of bright minds with deep fermentation experience.

- Published in Food & Flavor

‘Ferming’ the Future of Food

The New York Times latest food article deep-dives into the precision fermentation that produces alternative foods, biotechnology that could turn the agriculture industry “from farming to ‘ferming.’”

The American food system is unsustainable, according to the article, with factories and feedlots producing one-third of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions. But scientists have an answer for producing protein-rich, sustainable, cheap food: precision fermentation. Using this biotech method, components of animal products (such as beef or eggs) are isolated, and then their cells are multiplied in large vats. But scaling is proving problematic.

“Precision fermentation is the most important environmental technology humanity has ever developed,” says George Monbiot, an ecologist and journalist. “We would be idiots to turn our back on it.”

Startups are lacking infrastructure and even knowledgeable employees “in a food industry trained to support animal farming.” Dr. Liz Specht, vice president of science and technology at the Good Food Institute, says we’re living in a “critical moment for governments to invest,” similar to what’s been done in the renewable energy sector in recent years. Regulations and intellectual property are also concerns.

Read more (The New York Times)

Will Fermentation Connect Gastronomy and Biotech?

Fermentation is motivating scientists to listen to gastronomers, a rare occurrence in the field of science.

“There’s going to be a huge exchange in this two-way road that we’re living in. Innovation in flavor coming from gastronomy and innovation coming from a high-level biotechnology, they are going to be harmonious,” says Jason White, director of the fermentation lab at Noma in Copenhagen. “We’re going to be able to create this infrastructure and community of people who have the same goal, and the same goal is going to be the wellness of our planet.”

White spoke at the 2nd international Food Innovation Conference. This annual gathering of industry experts is produced by the Gottlieb Duttweiler Institute (GDI), Switzerland’s oldest independent think tank, which researches the future of food, retail and health.

The conference focused on the future of fermented alternative proteins. Or, as GDI puts it: “how innovation can solve the carnivore conundrum.” Speakers included the founders of numerous precision fermentation companies, such as SuperBrewed Food, Bosque Foods, Melt&Marble and WNWN Food Labs.

“We do the same thing, we just have different outputs”

Fermentation for alternative proteins is a divisive topic among traditional fermenters. Many say it’s lab-created fake food. Advocates, though, argue precision fermentation using DNA from mammals (as with Impossible Foods’ heme protein burger) and biomass fermentation of fast-growing, naturally-occurring organisms(e.g., Nature’s Fynd fungi protein) are reducing the risk of a global food crisis. Meat consumption is increasing, but animal meat is environmentally inefficient to raise. The significant amounts of agricultural land, fertilizer, pesticide and hormones needed to raise animals for meat protein release harmful carbon emissions.

The chefs on GDI’s “Fermentation: A World Within Gastronomy” panel spoke favorably of using fermentation for alt foods. White was joined by Ezio Bertorelli, co-founder of fermentation shop Meta Copenhagen, and Sirkka Hammer, founder of food manufacturer Wiener Miso in Austria.

“I think that it’s important for us not to steer too far away from the origins of fermentation,” White notes. But, “whether you have this bioreactor filled with whatever working inside of a laboratory with a team of scientists, we are still creating something that comes from microorganisms and from organisms. And so we do the same thing, we just have different outputs, different audiences.”

Precision fermentation technology is rooted in traditional fermentation, he notes. You need to understand the abilities of microbes and composition of ingredients for a successful precision fermentation.

“Inside of these laboratories and restaurants, there’s so many things that are being discovered that stop at the guest experience,” White says of fermentation. Today, as fermentation continues a revitalization as a kitchen craft, it’s utilized by more people rather than just chefs and scientists.

DIscovering Fermentation

Hammer highlighted the boom in home fermentation, with people creating the bold flavors of fermented foods and beverages on their own countertops.

“There’s a certain magic in fermentation. That’s why you’re gripped with it,” she says. “People are bringing a little bit of that magic, uncontrollable magic maybe [into their homes].”

At Wiener Miso, Hammer launched the company’s umami-driven ferments after living in Asia for more than a decade. The spices, pastes and sauces she makes are based on traditional Japanese ferments.

“Fermenting gives you in gastronomy next level or an add-on of flavors and textures,” she says. “Fermentation really changes the texture in a different way than if you cook it or freeze it. It gives it new dimensions.”

Flavor is what introduced Bertorelli to fermentation, too. His background is in professional cooking – he is the former executive chef of La Petite Table in Paris – but he was always experimenting with miso and sauerkraut in his home kitchen.

Even today, his fermentation experiments “go terribly wrong most of the time,” says Bertorelli. Only about 5% are successes, “that’s what makes it exciting.”

“Fermentation really changed my life because it showed me most of the dishes I was passionate about, the origin of the flavor, was the fermented part,” he says. “Flavor is universal… If you have that mind-blowing moment, it can reconnect you with things that are inside all of us, like our ancestors have been eating these foods since thousands of years ago and it’s sort of like going back in time while still being here.”

- Published in Food & Flavor

State of Fermentation for Alt Proteins

The world of fermentation-enabled alternative proteins is growing rapidly. Investments in these producers tripled in 2021 to $1.69 billion, and the number of companies increased by 20%.

“It’s really cemented fermentation’s position within alternative proteins and their investment landscape,” says Sharyn Murray, senior investor engagement specialist for the Good Food Institute (GFI). Over $5 billion was invested in alternative proteins last year. “It really demonstrates the central place that alt proteins hold for investors when they consider the future of food.”

Murray and other GFI leaders shared these and other dimensions of the alternative protein space during their annual State of the Industry virtual report. Below are highlights.

Scaling Challenges

Infrastructure is the biggest stumbling block for fermented alternative protein companies.

“The elephant in the room, perhaps the greatest hurdle that alternative protein fermentation effects and the alt protein industry as a whole will face over the next decade, is the looming shortage of available fermentation manufacturing capacity,” says Ryan Dowdy, GFI’s science and technology analysis manager.

Roughly 95% of the existing precision fermentation facilities are outdated and not configured for food production – many were made for pharmaceutical or ethanol production. More precision fermentation capacity was lost in 2021 than added, GFI reports.

Pressing is the need to meet global demand for protein by 2030. That goal, Dowdy notes, will require three times the fermentation capacity that is available today. Companies are building their own facilities – like The Better Meat Co. in Sacramento, Nature’s Fynd in Chicago (pictured Nature’s Fynd CEO Thomas Jonas in their new facility) and Mycorena in Göteborg, Sweden.

Hybrid Products Growing

Alternative food products have typically been categorized in three ways: plant-based, fermented and cultivated. GFI still divides their annual report along those three groupings.

But Audrey Gure, GFI’s startup innovation specialist, says, in the future, “we won’t see alternative protein production platforms as distinct industry segments but really rather one large industry where we produce animal product alternatives across the spectrum utilizing ingredients from one or more technologies to achieve the desired sensory and functional properties. Fermentation will play a critical role in these hybrid products.”

Hybrid examples include alt beef derived from cultivated cow cells that have been grown using fermentation techniques, and plant-based collagen made with fermentation-derived ingredients.

“Fermentation also holds disruptive power for other products made from animals beyond meat, eggs, dairy and seafood,” Gure continues, like “infant nutrition, pet food, honey collagen and gelatin are additional product categories that are seeing fermentation innovations.”

What’s in a Name

Nomenclature and labeling continue to be hotly debated.

“In terms of names used, companies are not completely aligned,” notes Madeline Cohen, GFI’s regulatory attorney.

Though companies have come to a consensus on using the term “animal free,” other descriptors used in the fermented alternative protein spaces are contested. For example, biomass fermentation is called Fermotein by The Protein Brewery and Fy by Nature’s Fynd. Brave Robot, Graeter’s and Starbucks all use Perfect Day’s alternative dairy proteins, but the ice cream producers call it “animal-free dairy” while Starbucks says“animal-free milk.”

In Europe, traditional dairy terms like “milk” and “yogurt” are legally prohibited for use by alternative dairy companies. But the European Parliament in 2020 rejected a similar bill for meat producers. If passed, alt meat companies would not have been able to use traditional meat terms like sausage or burgers for products not derived from an animal carcass. GFI notes several companies in the industry are working together to establish verbiage.

- Published in Business

- 1

- 2