FDA: Pickles & Yogurt “Unhealthy”?

Pickle and yogurt brands are speaking out against new labeling rules proposed by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. The FDA’s new guidelines say some brands of the fermented products cannot be marketed as healthy because pickles are too salty, while some yogurt has too much sugar.

The guidelines are being updated for the first time since the 90’s. They redefine what can be labeled as “healthy” on a food package. Healthy products have high amounts of key nutritious ingredients, like fruits and vegetables, and low amounts of added sugar, sodium and/or saturated fat. Those updated nutrient content claims would go into effect in 2026. They wouldn’t ban “unhealthy” foods, but prevent the use of “healthy” on a label.

“Pickles have a role to play in a healthy diet because they are predominantly comprised of vegetables and serve as a delicious condiment to other nutrient-dense foods,” Pickle Packers International said in a statement.

Though pickles are made from low-sodium cucumbers, they are either fermented through a brine made of water, salt and seasonings or preserved in a brine of vinegar, salt and seasonings. Without enough salt in the brine, bacteria can grow and spoil the pickles. The new guidelines put the limit for sodium from a vegetable product at 10% of the daily value per serving (230 milligrams per serving). But most pickles include 11% sodium per serving.

Yogurt, too, is under fire. The new guidelines outline that a ¾ cup of yogurt should only include 5% per serving of the daily value of sugar (2.5 grams of added sugar per serving). Chobani’s plain greek yogurt includes 5.5 grams of sugar per serving. Chobani has actively protested the FDA’s ruling, noting that “reducing sugars to the level proposed by FDA for the ‘healthy’ claim would result in significant, deleterious effects to product quality, taste, and texture.”

Other companies are protesting the FDA’s guidelines – like General Mills, Kellogg’s, SNA International, the National Pasta Association and the Consumer Brands Association. The FDA guidelines put tighter restrictions on cereal and pasta, too.

“Hardly anything would qualify, so of course food manufacturers don’t like the idea,” says Marion Nestle, emeritus professor of nutrition and public health at New York University. She told nutrition and medicine publication STAT that the FDA’s regulation “automatically excludes the vast majority of heavily processed foods in supermarkets, as well as a lot of plant-based meat, eggs, and dairy products,” from bearing the healthy claim.

The publication notes nutrition experts gave “overwhelmingly positive remarks.” The new guidelines are supported by the American Society for Nutrition, the Association of State Public Health Nutritionists and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Some experts argued the GDA could go further in restricting the healthy label.

Read more (STAT)

- Published in Food & Flavor, Health

Fermenting Cacao Enhances Health Benefits

Fermenting cacao beans to make chocolate decreases the amount of healthy antioxidants polyphenol by as much as 18%. So shouldn’t chocolate made from unfermented cacao beans increase the health benefits of chocolate? Scientists at Penn State explored this hypothesis. The results were surprising.

“In fact, just the opposite,” says Joshua Lambert, professor of food science at Penn State who led the study. “We found that some of the most processed samples seemed to have the largest positive impact on mice in this research. The aim of this study was to compare the effect of fermentation and roasting protocols on the ability of cocoa to mitigate obesity, gut barrier dysfunction and chronic inflammation in high-fat-fed, obese mice.”

The results, published in the Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry, detail how the health of mice was affected after being fed dietary cocoa powder. Groups of obese mice were fed seven different dietary supplements of cocoa powder over eight weeks. Those seven powder supplements were formulated from different bean processing techniques, ranging from no fermentation and no roasting to various combinations and temperatures.

The mice’s weight reduced by up to 57% eating cocoa powder, regardless of the bean’s fermenting and roasting techniques. Their gut permeability (an important contributor to development of fatty liver disease) also reduced by up to 79%. The gut intestinal microbiome also improved.

Lambert explains, when mice get cocoa as part of their diet, the compounds in the cocoa powder reduce the digestion of dietary fat. When it can’t be absorbed, the fat passes through their digestive systems. Lambert hypothesizes this process may occur if humans are given cocoa.

Read more (Penn State)

- Published in Uncategorized

Sourdough Fermentation & Gut Health

Sourdough is being researched for its effectiveness in helping people with celiac disease and gluten sensitivities. Charlene Van Buiten, PhD, an assistant professor of food science and human nutrition at Colorado State University, shared how sourdough can alleviate problems with gut health in an article she wrote for Baking Europe.

The live, active cultures contained in fermented foods like kimchi, pickles, kombucha and yogurt have been scientifically proven to increase the diversity of microorganisms in the digestive tract. A recent study from researchers at Stanford found a diet rich in fermented foods decreases markers of inflammation.

The same health benefits cannot be attributed to sourdough, though, because the live microorganisms are killed during baking.

“As a result, the health benefits associated with sourdough bread are derived not from probiotics, but from the actions of the starter culture over the course of fermentation,” Van Buiten writes. The microorganisms present in starter cultures “have been shown to improve mineral bioavailability in sourdough bread in comparison to conventional yeast-fermented bread through the production of organic acids and enzyme phytase, which promote the degradation of anti-nutritional phytates found naturally in flour. “

Sourdough bread has other positive effects, too. The increased acidity of sourdough forms resistant starch, so starch is not converted to sugar by the gastrointestinal tract but instead “acts more like fiber.” Sourdough fermentation also increases the amount of free amino acids in bread, improving the protein digestibility. Sourdough bread made from starter cultures are also lower on the glycemic index.

Van Buiten points out case studies “have suggested that traditional sourdough fermentation can improve gastrointestinal tolerance to bread in comparison to conventional yeast fermentation,” but only for individuals with non-celiac gluten sensitivity. Few studies have explored how sourdough would impact someone with celiac. A study would need to explore gluten degradation within sourdough fermentation, a key sensitivity for individuals with celiac.

“Though no evidence currently exists where traditional artisanal sourdough fermentation provides protection against the harmful gluten peptides associated with celiac disease pathogenesis, scientists are exploring novel strategies to employ the known gluten-degrading capabilities of sourdough-derived microorganisms in the production of baked goods,” Van Buiten adds.

Read more (Baking Europe)

Electric Kombucha

In the last few years, entrepreneurial scientists have found creative uses for the kombucha SCOBY mother used to make new products. The latest: using SCOBY as a malleable surface to print circuit boards.

Researchers at the University of the West of England, Bristol, discovered the dried mats made from the cellulose of the SCOBY make flexible, cheaper, lighter and more eco-friendly circuit boards for electronics. And because these kombucha mats are non-conductive, they’re also safer. Andrew Adamatzky, professor at the university and one of the researchers, says they tested the SCOBY mat with tiny LEDs on the circuits, which still worked after stress tests.

“Nowadays kombucha is emerging as a promising candidate to produce sustainable textiles to be used as eco-friendly bio wearables,” Adamatzky, tells New Scientist. “We will see that dried — and hopefully living — kombucha mats will be incorporated in smart wearables that extend the functionality of clothes and gadgets. We propose to develop smart eco-wearables which are a convergence of dead and alive biological matter.”

Researchers hope kombucha electronics can soon be used as wearable electronics, like heart rate monitors.

The discovery is another in a unique lineup of SCOBY-based innovations. Alternative “leather” closes made from SCOBY were designed by an Iowa State professor in 2016, SCBOY water purifiers were designed by a Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Imperial College London scientists in 2021 and a SCOBY wood alternative called Pyrus was designed by University of Illinois student in 2021.

Read more (ARS Technica)

- Published in Science

Exploring Fermentation & Health with David Zilber

We cannot write-off pasteurized ferments as the dead, less healthy cousin to its unpasteurized, live relative. All fermented foods provide health benefits, pasteurized or not. We also need to avoid getting caught up in superfluous health claims around fermentation’s benefits. Instead, we should focus on including fermentation as part of a regular diet.

David Zilber explored how the microbial transformation of food intersects with our gut microbes during Stanford University’s Center for Human Microbiome Studies Fermentation & Health Speaker Series. With growing scientific interest in fermentation – and increasing interest from consumers – the health benefits become cloudy in marketing claims.

“If you eat regularly foods full of life, life that lives regularly in the foods you consume but also inside of you, then you can be said to be a ranger taking care of a healthy forest,” Zilber said. “The health benefits of fermented foods should equally be viewed as being meaningful when they turn into a regimen, like exercise.”

Health Claims

A 2021 study by Stanford researchers published in the journal Cell found regularly eating fermented foods boost microbiome diversity, improves immune response and decreases inflammation. But marketing of fermented products is often shrouded in hearsay.

“As far as health claims go…(there are) sometimes outlandish claims made by Westerners about cure-all superfoods that disproportionately, and I quote from one study I found, ‘Seemed to benefit the individuals that sell them the most,’” Zilber said.

Take kombucha, for example. He rattled off a list of health problems kombucha founders have claimed the fermented tea has cured, from AIDS to cancer to constipation.

“The problem is that all these claims seem to come, in one form or another, from anecdotes of people who drink kombucha and have lived a life,” he added. They’re not researched in reputable cohort studies. “This is why it’s sometimes hard to separate the wheat from the chaff when it comes to fermentation. The people who want to believe the benefits only decry its Praises when a positive correlation is made but they also tend to speak the loudest.”

Zilber pointed out that consuming fermented foods, whether or not it’s a product with proven health benefits, is certainly still beneficial. Eating fermented foods regularly means “you’re also omitting a whole slew of other foods” prevalent in a Western diet, like highly-processed and chemically-preserved foods.

“If you put kimchi on your plate at dinner, you leave off mashed potatoes. If you use water kefir as your drink with it, you aren’t drinking Coke,” he said. “And that’s an important link we also can’t forget, when it comes to thinking about the health benefits of fermented foods, they are in many means inherently healthy.”

Many cultures have fermented for thousands of years to preserve food. In Tibet, yak herders rely on cultural wisdom passed down from generations to ferment yak’s milk for milk and butter.

“We’ve evolved alongside our microbes both evolutionarily and culturally,” Zilber added. “To Tibetans their folk knowledge of what leads them to Long lives and health is intrinsically tied to the practices of preservation that have allowed them to thrive in some of the most rarified air on Earth.”

Pasteurized vs. Unpasteurized

What about purchasing pasteurized vs. unpasteurized ferments? Unpasteurized ferments include live microbes, but that doesn’t mean pasteurized ferments aren’t healthy.

“Sometimes in cooking, if you’re looking to achieve a great flavor, sometimes you have to kill microbes because you have to pasteurize them for whatever number of reasons,” Zilber added. But it doesn’t mean that the food is somehow not worth eating, it just means that it’s not live, but it still contains lots of benefits. … There is a benefit to consuming something that microbes have lived through, even if it’s not pasteurized.”

Elisa Caffrey, the speaker series host and a Stanford PhD candidate, agrees. The benefits of unpasteurized ferments have not been studied. During fermentation, Caffrey notes, the microbes are producing metabolites still present during pasteurization. A complete study would characterize the metabolites over the course of the fermentation process, identify chemical compounds and then analyze the compounds for their benefits.

“That landscape we don’t understand at all and it’s a very, very interesting world to start exploring,” she said. “Until we start understanding all the different components of these foods and the way that they interact with not only the microbes in fermented foods with each other but also with the body, it’s really hard to then make these very generalized health claims.”

Caffrey, Zilber and Justin Sonnenburg, PhD, professor of microbiology and immunology at Stanford, host the Fermentation & Health Speaker Series. The series will explore the topic over the next few months with different speakers ranging from a scientist, food researcher and pickle producer. Registration is free.

Fermentation is Not a Trend

Fermentation intersects several major food movements – it’s natural, artisanal, sustainable, innovative, functional, global, flavorful and healthy. Now is an ideal time in the food market for fermentation producers.

“Fermentation is not a trend. It’s experiencing a resurgence, a renaissance,” says Amelia Nielson-Stowell, editor of The Fermentation Association. “Fermentation never went away. It just became less of a common type of food craft, especially in the U.S. where Americans became accustomed to other types of food processing.”

Nielson-Stowell was a speaker at the Specialty Food Association’s Winter Fancy Food Show in Las Vegas. Her remarks touched on growth opportunities and challenges for the fermentation industry. It was well-received by the audience. Two food business news magazines wrote articles about it. The show’s keynote speaker, author Paco Underhill, was also in attendance and brought up Nielson-Stowell’s presentation during his keynote.

Fermentation is a growing industry, slated to reach $846 billion in global sales by 2027. Kvass, pickles, kimchi and hard cider are the products experiencing the largest growth.

There’s no denying fermentation’s popularity – “there’s widespread scientific agreement that eating fermented foods will help the microorganisms in your gut,” Nielson-Stowell explains. But reputable clinical trials proving the health benefits of fermented foods are few and far between because they’re incredibly expensive to conduct. There are plenty of studies on the health benefits of yogurt because there’s a lot of money in the dairy industry. Other ferments don’t have the monetary backing, she adds.

Nielson-Stowell points to the 2021 Stanford study as a “watershed moment” in fermentation. It’s one of the first clinical trials proving diet remodels the gut microbiota. The research, published in the journal Cell, found a diet high in fermented food like yogurt, kefir, cottage cheese, kimchi, kombucha, fermented veggies and fermented veggie broth led to an increase in overall microbial diversity.

“This microbiome world we are in right now is a real opportune time to talk to consumers about fermented foods and health,” Nielson-Stowell said. “Humans have long consumed fermented foods for thousands and thousands of years, but now we have the scientific techniques to dive into fermented foods and analyze their nutritional properties, their microbial composition and better understand how they may improve a person’s health.”

Educating consumers is another major challenge. Nielsen-Stowell encourages brands to focus on simple messaging, then delve deeper into the science on their webpage for consumer’s that want to know more about the intricacies of their food.

“Many consumers are confused about fermentation. They know it’s good for them, but they don’t understand why or what products are fermented,” she said.

Tradition, too, should be shared.

“Fermented foods have a unique story to them compared to other foods,” she adds. “Every culture in the world has a traditional ferment. We are here today because, thousands of years ago, our ancestors fermented.”

- Published in Food & Flavor, Health

Better Bread: Study Proves Sourdough Wins

Plenty of anecdotal evidence lauds sourdough as the healthier bread alternative for those with wheat or gluten intolerance, but there is little research providing data on the topic. Now new research proves the longer a sourdough ferments, the better the bread.

Sourdough is a fermented bread fortified with dietary fibers, increased mineral bioavailability, lower glycemic index and improved protein digestibility compared to its unfermented counterparts. And, as more people shun traditional bread because of a wheat or gluten intolerance, sourdough is increasing in popularity.

Researchers at the University of Minnesota are studying the effects of dough fermentation and wheat varieties to create a bread that’s easier to digest. They found the longer fermentation time makes a more digestible bread. The results, published in November in the Journal of Cereal Science, found a 12 hour ferment versus a four hour ferment dramatically reduces the short-chain carbohydrates that aren’t absorbed properly in the gut.

“Wheat sensitivity seems to be getting worse,” says James Anderson (pictured, left), professor and wheat breeder at the University of Minnesota and one of the study authors. “The motivation for me as a wheat breeder to get involved in this research is the wheat sensitivity issue.”

Those short-chain carbs – FODMAPs (fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides and polyols) and ATIs (amylase/trypsin-inhibitors) – are what causes digestive problems in some people.

“There is evidence to document that sourdough processing or fermentation in general is able to reduce these FODMAPs and ATIs,” said George Annor (pictured, right), a professor of cereal chemistry and technology at the University of Minnesota and another of the study’s authors.

While fermentation time makes a difference in digestibility of sourdough, so do wheat varieties. Ancient grains such as Einkorn and Emmer performed well, same with the modern Linkert variety.

Though the study proves sourdough and other slow-rising breads can help those who are sensitive to wheat, the modern baking industry is dominated by sped up processing techniques. Like most commercial breads, frozen pizza crust and other convenience foods. Annor says he wants “them to keep those processes as much as they can,” but using a better wheat variety will aid digestibility.

“There’s more that we don’t know about fermentation than we do know, and it’s a wonderfully complex world,” says Brian LaPlante, a fellow Minnesotan and owner of Back When Foods.

LaPlante and his wife began making their own sourdough with ancient grains from his brother’s farm when LaPlante’s son began experiencing digestive problems. By incorporating sourdough and other fermented foods into his diet, his son’s health dramatically improved. LaPlante started his business Back When Foods that develops slow food with less processing – and hooked up with Anderson and Annor to help with their research. LaPlante provided the dough samples of varying ferment times that the UofM analyzed for their study.

“When you have fermented food in your diet, it has a profound impact on your microbiome,” he adds. “And I think that will be the trend, is food will become your medicine again.”

Gut Microbes Key to Exercise Motivation

A new study published in Nature reveals some new insight into the gut-to-brain pathway. Certain bacteria types boost our desire to exercise.

The study, performed on mice by researchers at the University of Pennsylvania, found differences in running performance based on the presence of gut bacterial species Eubacterium rectale and Coprococcus eutactus in the higher-performing mice. The metabolites known as fatty acid amides that the bacteria produce stimulate the sensory nerves in the gut, enhancing activity in the motivation-controlling region of the brain.

“If we can confirm the presence of a similar pathway in humans, it could offer an effective way to boost people’s levels of exercise to improve public health generally,” says Christoph Thaiss, PhD, an assistant professor of microbiology at Penn Medicine and a senior study author.

Researchers were surprised to find genetics accounted for only a small portion of performance differences in the mice. Gut bacterial populations were “substantially more important,” reads the study. Giving the mice antibiotics to get rid of their gut bacteria reduced the mice’s running performance by half.

“This gut-to-brain motivation pathway might have evolved to connect nutrient availability and the state of the gut bacterial population to the readiness to engage in prolonged physical activity,” says J. Nicholas Betley, PhD, an associate professor of Biology at the University of Pennsylvania’s School of Arts and Sciences and a study author. “This line of research could develop into a whole new branch of exercise physiology.”

Read more (Science Daily)

Fermenting Sustainable Food

The food industry is at the center of multiple bottlenecks hurting food production – global food crisis, extreme weather, supply chain disruption, inflation and geopolitical conflict. Researchers at Singapore’s prestigious Nanyang Technological University (NTU) have found a sustainable food solution: fermentation.

An article in New Food Magazine details the fermentation innovations of NTU and how they’re fermenting the edible by-products of food manufacturing to produce new food. Their food studies found great promise in okara (the “insoluble remains of soybeans from the production of soy milk and beancurd”) and spent grain (the “residual barley pulp from the beer industry”).

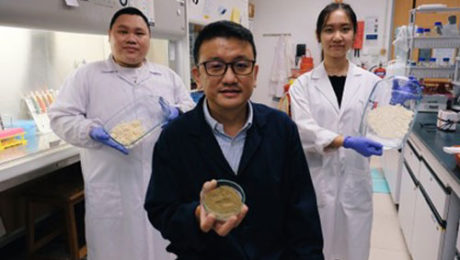

“Fermentation is a way to repurpose okara, a major food manufacturing side stream that is often discarded, and transform it into a highly nutritious food,” says Dr. Ken Lee (pictured), senior lecturer at NTU’s School of Chemistry, Chemical Engineering and Biotechnology, who led a study published in LWT – Food Science and Technology.

The study showed okara fermented with a mixed culture of the fungus Aspergillus oryzae and the bacterium Bacillus subtilis made a nutritional-rich food. This inoculated fermentation process is also used to make soy sauce.

Fermenting spent grain also makes a nutrient-rich, upcycled food: a protein-rich food emulsifier. A separate study by NTU researchers published in Food Chemistry found that plant-based food can replace dairy and eggs in condiments like mayonnaise, dressings and whipped cream.

“Upcycling food waste such as spent grain for human consumption is an opportunity for enhancing processing efficiency in the food supply chain, as well as potentially promoting a healthier plant-based protein alternative to enrich diets,” says Professor William Chen, professor and director of NTU’s Food Science and Technology Programme.

Read more (New Food Magazine)

- Published in Science

Microbes in Cheese

Do you love a mild mozzarella, a salty Parmesan or a funky brie? Thank microbes.

Though the thousands of varieties of the world’s cheeses all begin as a white lump of curd, the diversity is astounding. From the flavor to the color to the texture, cheese goes from “uniform blandness to this cornucopia” thanks to bacteria, yeasts and molds. An article in Smithsonian Magazine – titled The Science Behind Your Cheese – shares the details.

“More than 100 different microbial species can easily be found in a single cheese type,” says Baltasar Mayo, a senior researcher at the Dairy Research Institute of Asturias in Spain.

Scientists have only recently begun to study the microbial nature of cheese. To find out the bacteria and cheese present, scientists extract DNA from the cheese, then match it to genes in the database.

“The way we do that is sort of like microbial CSI, you know, when they go out to a crime scene investigation, but in this case we are looking at what microbes are there,” says Ben Wolfe, a microbial ecologist at Tufts University.

Though cheesemakers often add starter cultures of beneficial bacteria to fresh curds to transform it into a delicious cheese, Wolfe’s team found the microbiomes of the cheese “showed only a passing resemblance to those cultures. Often, more than half of the bacteria present were microbial ‘strangers’ that had not been in the starter culture,” continues the article.

Those “strangers” dumbfounded researchers. Microbes like Brachybacterium found in Gruyère are more commonly found in soil, seawater and chicken litter. Or the Halomonas most commonly found in salt ponds and marine environments. Or, Brevibacterium linens found in damp areas of skin, such as between the toes. Those bacteria come from the environment of the cheesemaking facilities. The microbes come from the cow, goat or sheep, the bacteria in the farm’s stable, the skin bacteria from the hand of the milker, the microbes in the dairy storage tank and/or the sea salt in the brine used to wash down the cheese. Hundreds of bacteria have been detected in long-ripened cheeses.

“Furthermore, by repeatedly testing, scientists have observed that there can be a sequence of microbial settlements whose rise and fall can rival that of empires,” continues the article.

Modern cheesemaking is, sadly, more controlled, meaning modern cheese isn’t as flavorful. Cheesemaking has “become tamer over time,” cleaner and more sterilized, filtered, pasteurized, machine operated.

“Many of our cheddars, provolones and Camemberts, once wildly proliferating microbial meadows, have become more like manicured lawns. And because every microbe contributes its own signature mix of chemical compounds to a cheese, less diversity also means less flavor — a big loss.”

Read more (Smithsonian Magazine)

- Published in Food & Flavor, Science