Fermenting Cacao Enhances Health Benefits

Fermenting cacao beans to make chocolate decreases the amount of healthy antioxidants polyphenol by as much as 18%. So shouldn’t chocolate made from unfermented cacao beans increase the health benefits of chocolate? Scientists at Penn State explored this hypothesis. The results were surprising.

“In fact, just the opposite,” says Joshua Lambert, professor of food science at Penn State who led the study. “We found that some of the most processed samples seemed to have the largest positive impact on mice in this research. The aim of this study was to compare the effect of fermentation and roasting protocols on the ability of cocoa to mitigate obesity, gut barrier dysfunction and chronic inflammation in high-fat-fed, obese mice.”

The results, published in the Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry, detail how the health of mice was affected after being fed dietary cocoa powder. Groups of obese mice were fed seven different dietary supplements of cocoa powder over eight weeks. Those seven powder supplements were formulated from different bean processing techniques, ranging from no fermentation and no roasting to various combinations and temperatures.

The mice’s weight reduced by up to 57% eating cocoa powder, regardless of the bean’s fermenting and roasting techniques. Their gut permeability (an important contributor to development of fatty liver disease) also reduced by up to 79%. The gut intestinal microbiome also improved.

Lambert explains, when mice get cocoa as part of their diet, the compounds in the cocoa powder reduce the digestion of dietary fat. When it can’t be absorbed, the fat passes through their digestive systems. Lambert hypothesizes this process may occur if humans are given cocoa.

Read more (Penn State)

- Published in Uncategorized

Bean-free Chocolate & Coffee

The front page of the Financial Times featured a new wave of alternative foods: chocolate and coffee, but without the beans.

Cultivating both cocoa beans for chocolate and coffee cherries for coffee at such a high rate for global consumption is damaging to the environment. It’s linked to deforestation. The working conditions for many of the farmers are also deplorable, with child and slave labor and poor wages. Now multiple startups are trying to make a market for bean-free products.

“You realise that a lot of our favourite foods, whether it’s beef burgers or a cult of coffee or a chocolate bar, there’s so much damage,” said Johnny Drain, chief technology officer of WNWN Food Labs, a London-based maker of cocoa-free chocolate. “Not just to the climate but to the people, typically in developing countries who are producing those products for us.”

Drain is a fermentation expert who formerly worked with restaurants to make unique flavor profiles using fermentation. He’s founded WNWN with Ahrum Pak, a former financier now working in the foodtech space with Drain (both pictured). Their chocolate is made from fermented barley and carob.

More startups are, too, trying to be a solution to an unhealthy chocolate and coffee industry. In Munich, Planet A developed a cocoa-free chocolate which has chief ingredients of fermented oats and sugar beet. They call it “Nocoa.” In the U.S., Voyage Foods and California Culture make chocolate from lab-grown cocoa.

Bean-free coffee, meanwhile, has been created by two U.S. startups – Atomo in Seattle uses date seeds, chicory root, grape skin and green tea to create a canned cold brew coffee. Compound Foods in San Francisco. The latter is recreating coffee using synthetic biology and fermentation.

“We want to give consumers a choice,” said Andy Kleitsch, co-founder of Atomo, who added that although they had been worried that “the coffee industry would hate us or that the baristas might hate us, the reception has been positive”.

Many of these entrepreneurs note alt products are not the only solution to an environmentally-damaging food industry. Drain adds: “It’s just one additional way of trying to change an industry that is built on inequity and slave labour.”

Read more (Financial Times)

- Published in Business, Food & Flavor

Can Science Improve Chocolate?

Just like wine and coffee, the flavors of chocolate come from the local terrain, climate and soil where the cacao bean is grown. Chocolates from various parts of the world all taste different. Can those tastes be replicated?

Scientists are trying to determine what produces those flavors and if they can reproduce them consistently. Irene Chetschik, professor in food chemistry at Zurich University of Applied Sciences, has developed “new technological processes that can impact cocoa flavor on a molecular level — to get the best out of each harvest and create consistent quality,” details an article in BBC.

Chetschik says: “Now there is more appreciation for the product – we know where the bean is coming from, which farm, which variety – we can experience a much wider flavor diversity.”

Cocoa beans traditionally are fermented where they are grown. Fermentation will affect quality – a poorly-fermented bean has little flavor; while an over-fermented bean can become too acidic.

Chetschik has developed a “moist incubation” fermenting technique where a lactic acid solution containing ethanol is applied to dried cocoa beans. It triggers the same fermentation reaction in the beans, “but is far easier to control,” she says. The final taste is sweet, rich and fruity.

Nottingham University is also working on a chocolate-enhancing project. They’re using a hand-held DNA sequencing device to analyze the cocoa bean microbes. “With improved understanding of what drives the taste of premium chocolate, fermentation can be manipulated for improved flavor.”

Read more (BBC)

- Published in Food & Flavor, Science

World’s Rarest Foods in Danger of Extinction

Journalist Dan Saladino explores the world’s endangered foods in his new book Eating to Extinction: The World’s Rarest Foods and Why We Need to Save Them. He argues that the world could lose culinary diversity. “The story of these foods, and the way in which they’re presented in the book,” says Saladino, from wild foods associated with hunters and gathers, to cereals, vegetables, meats and more, “is really the story of us and our own evolution.”

A review of Saladino’s book in Smithsonian Magazine shares 10 of the world’s rarest foods — five of them fermented. These rarities include:

- Skerpikjøt (Faroe Islands, Denmark): Dried and fermented mutton made from the shanks and legs of sheep. It ferments in wooden sheds called hjallur, which have vertical slats that allow space for the salty sea wind to blow in.

- Salers cheese (Auvergne, France): One of the world’s oldest raw milk cheeses made from the milk of Salers cows. The semi-hard cheese is made with varying fermentation lengths, which change the flavor.

- Qvevri wine (Georgia): Winemakers fill the egg-shaped terracotta pots called qvevri with grape juice, skins and stalks, then bury the pots underground. The steady temperatures and the pot’s shape allows even fermentation.

- Ancient Forest Pu-Erh Tea (Xishuangbanna, China): The fermented tea is made from wild tea leaves that grow in China’s southwestern Yunnan province. The leaves are sun-dried, cooked, kneaded, then formed into solid cakes and fermented for months (or years).

- Criollo Cacao (Cumanacoa, Venezuela): The world’s rarest type of cacao, it represents less than 5% of the cocoa production on the planet. The bean lacks bitterness, but is difficult to grow.

Read more (Smithsonian Magazine)

- Published in Food & Flavor

San Francisco’s Growing Chocolate Scene

In San Francisco, a “booming Bay Area confection ring” is developing.. Julia Street, a former food tech industry exec, is the latest entrant. She is now a self-taught chocolatier running J Street Chocolate.

Street began pursuing chocolate “to follow her obsession with all things fermented.” The experimental chocolates “only a scientist could dream up” are made using upcycled ingredients from other fermenters in the city. For example, she uses spent grains from Laughing Monk Brewing in her Piv Snack Bars. She tells Eater that the ethics behind the chocolate are important to her, too. Her 68% cacao bar is sourced from the Dominican Republic, and sales support a Northern Dominican agroforestry project.

Other Bay Area chocolate shops that have cropped up in recent years include Dandelion Chocolate, Topogato and Kokak Chocolates.

Read more (Eater)

- Published in Business, Food & Flavor

Fermentation Tourism

The state of Pennsylvania has created a unique tourist experience, Pickled: A Fermented Trail. The self-guided, culinary tour showcases fermented food and drink from around the state.

The fermented trail is broken into five regional itineraries, and includes historic businesses, artisanal food makers and large producers. Stops range from an Amish gift shop that ferments root beer to a master chocolatier, from a kombucha taproom to a fermentation-focused restaurant, and from a fourth-generation cheesemaker to a convenience store that makes its own pickles, sauerkraut and vinegar. Mary Miller, cultural historian and professor, spent two years designing the trail.

“Cultured foods have been part of PA’s culinary culture since the beginning,” reads the Visit Pennsylvania Pickled: A Fermented Trail website. “Many groups that have migrated to Pennsylvania throughout history were fond of fermented foods for both health and flavor, as well as for preserving food through the winter.”

The website also features a history of fermented food and drink, both regionally and globally. It shares a brief overview of root beer, which was created in Pennsylvania as a sassafras-based, yeast-fermented root tea. And it notes that, while Germans brought sauerkraut to the state, the Chinese are believed to have been the first to ferment cabbage.

The fermented trail is one of Pennsylvania’s four new culinary road trips, along with those highlighting charcuterie, apples and grains. These paths aim to showcase the state’s culinary history, and preserve its foodways.

This unique culinary adventure — the first we have seen at TFA — could be a model for tourism in other states and countries.

Read more (Food & Wine)

- Published in Business

The Rise of Fermented Foods and -Biotics

Microbes on our bodies outnumber our human cells. Can we improve our health using microbes?

“(Humans) are minuscule compared to the genetic content of our microbiomes,” says Maria Marco, PhD, professor of food science at the University of California, Davis (and a TFA Advisory Board Member). “We now have a much better handle that microbes are good for us.”

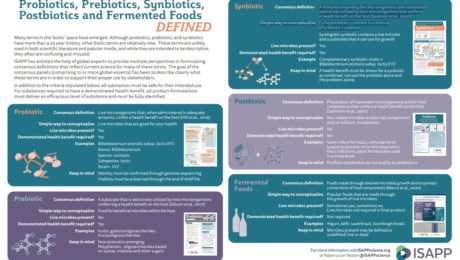

Marco was a featured speaker at an Institute for the Advancement of Food and Nutrition Sciences (IAFNS) webinar, “What’s What?! Probiotics, Postbiotics, Prebiotics, Synbiotics and Fermented Foods.” Also speaking was Karen Scott, PhD, professor at University of Aberdeen, Scotland, and co-director of the university’s Centre for Bacteria in Health and Disease.

While probiotic-containing foods and supplements have been around for decades – or, in the case of fermented foods, tens of thousands of years – they have become more common recently . But “as the terms relevant to this space proliferate, so does confusion,” states IAFNS.

Using definitions created by the International Scientific Association for Postbiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP), Marco and Scott presented the attributes of fermented foods, probiotics, prebiotics, synbiotics and postbiotics.

The majority of microbes in the human body are in the digestive tract, Marco notes: “We have frankly very few ways we can direct them towards what we need for sustaining our health and well being.” Humans can’t control age or genetics and have little impact over environmental factors.

What we can control, though, are the kinds of foods, beverages and supplements we consume.

Fermented Foods

It’s estimated that one third of the human diet globally is made up of fermented foods. But this is a diverse category that shares one common element: “Fermented foods are made by microbes,” Marco adds. “You can’t have a fermented food without a microbe.”

This distinction separates true fermented foods from those that look fermented but don’t have microbes involved. Quick pickles or cucumbers soaked in a vinegar brine, for example, are not fermented. And there are fermented foods that originally contained live microbes, but where those microbes are killed during production — in sourdough bread, shelf-stable pickles and veggies, sausage, soy sauce, vinegar, wine, most beers, coffee and chocolate. Fermented foods that contain live, viable microbes include yogurt, kefir, most cheeses, natto, tempeh, kimchi, dry fermented sausages, most kombuchas and some beers.

“There’s confusion among scientists and the public about what is a fermented food,” Marco says.

Fermented foods provide health benefits by transforming food ingredients, synthesizing nutrients and providing live microbes.There is some evidence they aid digestive health (kefir, sourdough), improve mood and behavior (wine, beer, coffee), reduce inflammatory bowel syndrome (sauerkraut, sourdough), aid weight loss and fight obesity (yogurt, kimchi), and enhance immunity (kimchi, yogurt), bone health (yogurt, kefir, natto) and the cardiovascular system (yogurt, cheese, coffee, wine, beer, vinegar). But there are only a few studies on humans that have examined these topics. More studies of fermented foods are needed to document and prove these benefits.

Probiotics

Probiotics, on the other hand, have clinical evidence documenting their health benefits. “We know probiotics improve human health,” Marco says.

The concept of probiotics dates back to the early 20th century, but the word “probiotic” has now become a household term. Most scientific studies involving probiotics look at their benefit to the digestive tract, but new research is examining their impact on the respiratory system and in aiding vaginal health.

Probiotics are different from fermented foods because they are defined at the strain level and their genomic sequence is known, Marco adds. Probiotics should be alive at the time of consumption in order to provide a health benefit.

Postbiotics

Postbiotics are dead microorganisms. It is a relatively new term — also referred to as parabiotics, non-viable probiotics, heat-killed probiotics and tyndallized probiotics — and there’s emerging research around the health benefits of consuming these inanimate cells.

“I think we’ll be seeing a lot more attention to this concept as we begin to understand how probiotics work and gut microbiomes work and the specific compounds needed to modulate our health,” according to Marco.

Prebiotics

Prebiotics are, according to ISAPP, “A substrate selectively utilized by host microorganisms conferring a health benefit on the host.”

“It basically means a food source for microorganisms that live in or on a source,” Scott says. “But any candidate for a prebiotic must confer a health benefit.”

Prebiotics are not processed in the small intestine. They reach the large intestine undigested, where they serve as nutrients for beneficial microorganisms in our gut microbiome.

Synbiotics

Synbiotics are mixtures of probiotics and prebiotics and stimulate a host’s resident bacteria. They are composed of live microorganisms and substrates that demonstrate a health benefit when combined.

Scott notes that, in human trials with probiotics, none of the currently recognized probiotic species (like lactobacilli and bifidobacteria) appear in fecal samples existing probiotics.

“There must be something missing in what we’re doing in this field,” she says. “We need new probiotics. I’m not saying existing probiotics don’t work or we shouldn’t use them. But I think that now that we have the potential to develop new probiotics, they might be even better than what we have now.”

She sees great potential in this new class of -biotics.

Both Scott and Marco encouraged nutritionists to work with clients on first improving their diets before adding supplements. The -biotics stimulate what’s in the gut, so a diverse diet is the best starting point.

The Fermentation-Flavor Connection in Chocolate

Cacao would never obtain its rich flavor profile without a traditional food processing technique: fermentation.

“I feel like fermentation adds about three-quarters of the flavor to the finished chocolate. I think it is the most important step in the entire tree-to-bar process for the flavor of the chocolate, and the chocolate makers have been taking too much credit for the flavor of their chocolate,” says Nat Bletter, PhD and founder of Madre Chocolate.

Chocolate makers “can definitely take a great grown and fermented cacao and make it shine, but it’s really hard to take a badly grown and fermented cacao and make a good tasting chocolate and that’s why so much of the world’s chocolate is loaded with milk and sugar to try to cover up some of the bad fermentation flavors.”

Bletter joined Max Wax (vice president of Rizek Cacao) and Dan O’Doherty (principal of Cacao Services) in sharing their expertise during a joint webinar, The Fermentation-Flavor Connection in Chocolate., co-hosted byThe Fine Chocolate Industry Association and The Fermentation Association..

The three speakers work in different size chocolate operations. Madre Chocolate is a small-scale chocolate making company in Honolulu that uses cacao from small Hawaiian farmers; Rizek Cacao is a producer and exporter of cacao and cacao products based in the Dominican Republic; and Cacao Services (also in Honolulu) s an agricultural and scientific consulting company that specifically focuses on cacao production systems.

Complex fermentation

Cacao fermentation is among the most complex of food ferments because it utilizes three families of microbes and 5-10 species in each. “It is a little bit hard to control since it’s not just one single species of microbes that you’re trying to support a good ecosystem,” Bletter adds.

Wax attributes less of chocolate’s flavor to fermentation. He says there are flavors produced by the metabolism of the plant itself, “so genetics is probably No. 1, then comes the terroir that comes with fermentation. We shouldn’t be dogmatic on fermentation but on the contrary open to this fantastic dialogue between wisdom and science.”

A chocolate maker is responsible for studying the effects of yeasts on their cacao ferment, Wax adds. They should ask: How does the naturally occurring yeast change flavor? What’s the metabolism rate? Is there a possibility of naturally inoculating the cacao for a different flavor?

“It is absolutely true that you should not inoculate something using either commercial yeast or yeast from grapes or other types of culture, or even from different environments,” Wax says. “But it is also true that the variety of yeast that is naturally occurring, not all of them give the same taste profile. … Nobody wants the same flavor and the same cacao forever, just as we don’t want the same wine or the same cheese or the same yogurt or the same beer.”

Rizek Cacao employs 32 varieties of yeast in their chocolate.

Sensory Cues

O’Doherty, who works with cacao farmers, says it’s possible to ferment cacao without any kind of quantitative measuring devices.

“If you’re an experienced fermenter and you really know what you’re looking at, you use all your senses,” O’Doherty says. A fermented cacao bean will be plump and juicy; the color will be reddish-brown (a pale bean is under-fermented) and the bean’s scent will change depending on the stage of the fermentation process.

“If I only had one sense to go on for cacao fermentation, I think it really would be aroma,” O’Doherty continues. The scent sequence will begin as fresh and fruity, transition to a strong yeast fragrance, next to wine , then to ethanol and, finally, the sharp vinegar scent will fade to a fruity vinegar.

One of the topics mostly frequently raised by cacao producers, says O’Doherty,is how to modernize their operations. He points out that most cacao farmers still ferment using boxes and heaps.

“In general, cacao cultivation and processing is centuries behind,” he says. Most cacao farms are run by small shareholders who don’t have the money for barrels or stainless steel equipment. “Sophisticated fermentation vessels are not really an option for consideration. Truth be told, well executed, both heaps and wooden box fermentations can produce some absolutely fantastic cacao.”

O’Doherty concludes: “The larger question about commodity cacao and the incentives or lack thereof is the reason that I have a job helping farmers with fermentation. Although there may be traditions, there’s no feedback mechanism. There is no incentive for good quality and, typically, there’s really not a penalty for bad quality, unless it is actually decomposing…a lot of the work I do is linking these producers that I assist with their harvest and process to chocolate makers that will pay double or triple the typical commodity price. I still don’t think that’s enough but it’s moving the needle in the right direction.”

- Published in Food & Flavor

Microbes & Chocolate’s Flavor

Love the rich flavor of chocolate? Thank microbes. Scientists are researching how fermentation affects the flavor of chocolate. An article in Scientific American details how a giant cacao seed pod naturally ferments.

Cacao has a wild fermentation, meaning the farmers who harvest the pods “rely on natural microbes in the environment to create unique, local flavors.” Just as grapes take on regional terroir (the characteristic flavor imparted by a place), “these wild microbes, combined with each farmer’s particular process, confer terroir on beans fermented in each location.” Demand for high-quality cacao beans is growing, and producers who make small-batch chocolate with distinctive flavors also are seeing sales growth.

Read more (Scientific American)

- Published in Food & Flavor, Science

Chocolate: Part of a Healthy Diet or Guilty Pleasure?

Does chocolate have a place in a healthy diet or is it a guilty pleasure? A new study found chocolate is good for the heart in moderate amounts. The study, printed in the European Journal of Preventative Cardiology, found eating chocolate more than once a week is associated with an 8% decrease in risk of coronary artery disease compared to those who eat chocolate less. Researchers note there are limitations — like the study didn’t account for type of chocolate or portion size. High-quality, low-sugar, dark chocolate, which is made with fermented cacao beans, has shown health benefits in other research.

Many major chocolate companies are trying to tout chocolate as a health food. Last year, chocolate producer Barry Callebaut petitioned the Food and Drug Administration to qualify the health claim that chocolate has heart benefits. The regulatory agency is still reviewing the request. This is the second time the Swiss company has petitioned the FDS to consider chocolate as a health food, but they were denied their first request in 2013.

Read more (Food Dive)

- Published in Food & Flavor, Science