Microbes on our bodies outnumber our human cells. Can we improve our health using microbes?

“(Humans) are minuscule compared to the genetic content of our microbiomes,” says Maria Marco, PhD, professor of food science at the University of California, Davis (and a TFA Advisory Board Member). “We now have a much better handle that microbes are good for us.”

Marco was a featured speaker at an Institute for the Advancement of Food and Nutrition Sciences (IAFNS) webinar, “What’s What?! Probiotics, Postbiotics, Prebiotics, Synbiotics and Fermented Foods.” Also speaking was Karen Scott, PhD, professor at University of Aberdeen, Scotland, and co-director of the university’s Centre for Bacteria in Health and Disease.

While probiotic-containing foods and supplements have been around for decades – or, in the case of fermented foods, tens of thousands of years – they have become more common recently . But “as the terms relevant to this space proliferate, so does confusion,” states IAFNS.

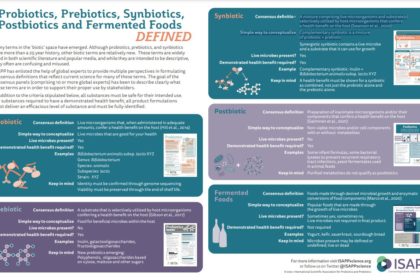

Using definitions created by the International Scientific Association for Postbiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP), Marco and Scott presented the attributes of fermented foods, probiotics, prebiotics, synbiotics and postbiotics.

The majority of microbes in the human body are in the digestive tract, Marco notes: “We have frankly very few ways we can direct them towards what we need for sustaining our health and well being.” Humans can’t control age or genetics and have little impact over environmental factors.

What we can control, though, are the kinds of foods, beverages and supplements we consume.

Fermented Foods

It’s estimated that one third of the human diet globally is made up of fermented foods. But this is a diverse category that shares one common element: “Fermented foods are made by microbes,” Marco adds. “You can’t have a fermented food without a microbe.”

This distinction separates true fermented foods from those that look fermented but don’t have microbes involved. Quick pickles or cucumbers soaked in a vinegar brine, for example, are not fermented. And there are fermented foods that originally contained live microbes, but where those microbes are killed during production — in sourdough bread, shelf-stable pickles and veggies, sausage, soy sauce, vinegar, wine, most beers, coffee and chocolate. Fermented foods that contain live, viable microbes include yogurt, kefir, most cheeses, natto, tempeh, kimchi, dry fermented sausages, most kombuchas and some beers.

“There’s confusion among scientists and the public about what is a fermented food,” Marco says.

Fermented foods provide health benefits by transforming food ingredients, synthesizing nutrients and providing live microbes.There is some evidence they aid digestive health (kefir, sourdough), improve mood and behavior (wine, beer, coffee), reduce inflammatory bowel syndrome (sauerkraut, sourdough), aid weight loss and fight obesity (yogurt, kimchi), and enhance immunity (kimchi, yogurt), bone health (yogurt, kefir, natto) and the cardiovascular system (yogurt, cheese, coffee, wine, beer, vinegar). But there are only a few studies on humans that have examined these topics. More studies of fermented foods are needed to document and prove these benefits.

Probiotics

Probiotics, on the other hand, have clinical evidence documenting their health benefits. “We know probiotics improve human health,” Marco says.

The concept of probiotics dates back to the early 20th century, but the word “probiotic” has now become a household term. Most scientific studies involving probiotics look at their benefit to the digestive tract, but new research is examining their impact on the respiratory system and in aiding vaginal health.

Probiotics are different from fermented foods because they are defined at the strain level and their genomic sequence is known, Marco adds. Probiotics should be alive at the time of consumption in order to provide a health benefit.

Postbiotics

Postbiotics are dead microorganisms. It is a relatively new term — also referred to as parabiotics, non-viable probiotics, heat-killed probiotics and tyndallized probiotics — and there’s emerging research around the health benefits of consuming these inanimate cells.

“I think we’ll be seeing a lot more attention to this concept as we begin to understand how probiotics work and gut microbiomes work and the specific compounds needed to modulate our health,” according to Marco.

Prebiotics

Prebiotics are, according to ISAPP, “A substrate selectively utilized by host microorganisms conferring a health benefit on the host.”

“It basically means a food source for microorganisms that live in or on a source,” Scott says. “But any candidate for a prebiotic must confer a health benefit.”

Prebiotics are not processed in the small intestine. They reach the large intestine undigested, where they serve as nutrients for beneficial microorganisms in our gut microbiome.

Synbiotics

Synbiotics are mixtures of probiotics and prebiotics and stimulate a host’s resident bacteria. They are composed of live microorganisms and substrates that demonstrate a health benefit when combined.

Scott notes that, in human trials with probiotics, none of the currently recognized probiotic species (like lactobacilli and bifidobacteria) appear in fecal samples existing probiotics.

“There must be something missing in what we’re doing in this field,” she says. “We need new probiotics. I’m not saying existing probiotics don’t work or we shouldn’t use them. But I think that now that we have the potential to develop new probiotics, they might be even better than what we have now.”

She sees great potential in this new class of -biotics.

Both Scott and Marco encouraged nutritionists to work with clients on first improving their diets before adding supplements. The -biotics stimulate what’s in the gut, so a diverse diet is the best starting point.