The Flavor Whisperer on Fermentation

Flavor is much more complex than just taste. Flavor can be collected, extracted, infused, created and transformed. And, in a billion-dollar flavor industry devoted to putting flavors into processed foods, fermentation is the oldest and most natural flavor creator, developing new flavors at a molecular level.

“Fermentation as a flavor creation process in collaboration with microbes, there’s almost no limit to how you can apply it and use the ingredients around you and have a more flavorful palette to work from,” says Arielle Johnson, PhD, a flavor scientist, gastronomy and innovation researcher and co-founder of the Noma Fermentation Lab.

A food chemist dubbed the flavor whisperer, she works with restaurants on innovating dishes and cocktails. She researches how flavor is perceived and is writing a book on her studies, Flavorama. Her work comes together in “all things science and cuisine have to say to each other.”

This week Johnson shared her insights into flavor and fermentation as a guest lecturer at Harvard University’s Science & Cooking series.

Taste & Smell Receptors

Flavor can be quite complex – Johnson calls it a black box.

There are five primary tastes: sweet, sour, salty, umami and bitter. Each taste evolved to ensure humans get basic nutrition. We use sweet foods for the energy in sugar, sour ones for vitamin C from fruit and fermented foods. Salty foods provide the essential mineral sodium. We seek umami foods for the taste of glutamine, an amino acid in proteins and fermented foods.

But bitter, Johnson points out, doesn’t sense one thing. It senses multiple molecules that are potential toxins for us. This is why bitter is called an acquired taste.

Smell is Johnson’s favorite part of the flavor profile. In order to taste, we must smell, too. Molecules land in the olfactory receptors in the nasal cavity and help activate taste. This is why food is tasteless if you plug your nose while eating. But the back of the throat is also connected to the nasal cavity, so the throat becomes “the secret backdoor” for sensing flavor.

While there are five major tastes and four receptor areas on the tongue, there are 40 billion smellable molecules and 400 receptors for smell.

Supertasters vs. Nontasters

Taste and smell, she detailed, help us understand how fermentation works.

The population can be divided into supertasters or nontasters. During her presentation, Johnson had the audience put a strip of filter paper on their tongue. The paper included a harmless bitter molecule phenylthiourea (PTC), but only roughly half the class could taste it. This group are supertasters – the group who could not taste the PTC are nontasters.

She explained everyone has different density of their taste buds. Supertasters have more taste buds, so more taste receptors signals are sent to their brains. This has culinary implications. Because their sense of taste is more sensitive, flavors are intense and supertasters have a less adventurous palette. Meanwhile nontasters have dulled senses, so it takes a lot of flavor to activate taste.

“The good news for supertasters is that fermentation is usually salty and sour and often umami – all of which counteract bitterness,” Johnson says. “Fermentation is a way to create new flavors but also transform ingredients.”

Fermentation as Flavor

Though “microbes are opportunistic” and pop up in foods whether planned or not, fermentation can’t be forced, Johnson says. When making a sauerkraut, for example, microbes don’t need to be added. Fermentation works with what’s on the surface of the cabbage and on the producer’s hands.

Salt is key in fermentation as a flavor additive, a preservation element and a safety measure. Salt filters out bad molds and avoids letting a ferment spoil. Other factors “dial in the flavors in this molecular flavor creation process,” she says, like the correct ingredients, temperature control and humidity.

“We’re really excited about microbes and fermentation,” Johnson says. “In this process of this exponential growth that microbes do, they’re eating things, they’re getting energy, but they’re also running their regulator metabolism. So there’s all these waste products that are not very significant to the microbes, but that can create a lot of interesting flavor complexity.”

- Published in Food & Flavor, Science

Fermentation for Global Health

Though scientists and environmentalists have warned about the dangers of increased meat consumption, Americans’ appetite for it is not slowing down. The last three years marked the largest amount of meat produced on record.

“People know about the harms of industrial agriculture, but people eat more and more and more meat,” says Bruce Friedrich, CEO of the Good Food Institute (GFI). “It’s an inextricable rise despite more and more attention to the issues. The vast majority of people are just not going to apply ethical considerations to their food choices.”

Fermentation, Friedrich declares, can be part of the solution. “Fermentation can be so powerful for global health, climate and biodiversity,” he says.

Friedrich spoke at FERMENTATION 2022 on alternative protein innovation. GFI, a nonprofit, aims to accelerate the innovation of fermented, plant- and cell-based alternative meat. But the young, rapidly-growing alt protein industry faces major obstacles in scaling, regulation, pricing and consumer acceptance. Friedrich told a room of professional fermenters at the conference to consider shifting to a career in alternative proteins.

“Anyone involved in fermentation, you have the expertise in knowledge. It’s cross-applying the skills and interest in your professional life into this new field,” he says. “One of the significant barriers for all the companies doing this is talent, which is to say – you.”

Global Agriculture Crisis

Friedrich does not mince his words: we’re on the precipice of a major environmental and health crisis if we don’t reduce meat consumption.

Mass producing meat is “extraordinarily inefficient.” Huge amounts of crops are grown to feed livestock so humans can then eat the animals.. “We have been using an antiquated method to produce meat for 12,000 years,” Friedrich adds.

Internationally, 4 billion hectares of land are used for agriculture – 3 billion are for grazing livestock or to grow their food. It takes 9 calories of feed to produce 1 calorie of chicken; 40 calories to produce 1 calorie of beef.

“This is an incredibly inefficient way to try and feed the world,” Friedrich says.

And it’s getting worse. By 2050, global meat consumption is projected to increase – conservative estimates say 50%, while others go as high as 260%.

Animal agriculture also is thought to be a major contributor to global climate change and a major factor in deforestation. Livestock are pumped with antibiotics, creating resistance in humans that consume that meat.

Future of “Meat”

The answer isn’t necessarily a world of vegetarians – it’s to change traditional meat.

Friedrich compares the situation to renewable energy and electric vehicles. For decades, government leaders have preached reducing fossil fuel consumption. But, as populations have risen, so has energy consumption.

“You are not going to convince people to consume less energy,” he says. “What you need to do is replace fossil fuels with renewable energy.”

Similarly with meat, there cannot be a meatless world. “This is innovation focused, it is not about behavior change,” he says.

“GFI when we started, we were talking about disrupting animal agriculture. We very quickly realized our hope is to transform industrial animal agriculture,” he says. “Things will happen a lot more quickly if we have the major corporations on board.”

GFI is “enthusiastically working with the biggest companies in the world:” JBS, Tyson, Smithfield, Cargill and BRF, the five largest global meat producers.

The aim is not to regulate big agriculture or stop subsidies. GFI hopes to open access into the science behind alternative proteins, incentivize the private sector to continue R&D and encourage government funding.

“The same sort of cash breaks that allowed Tesla to be successful should apply to Nature’s Fynd and Impossible Foods and others if they want that money,” Friedrich says, listing two major companies in the alternative protein industry. “Our global battle cry is that governments should be funding alternative proteins.”

Food Trifecta

By not gatekeeping alt protein technology, Friedrich says GFI is helping perfect the process of giving consumers the exact same meat experience, but using plant- or cell-based meats. People want the food trifecta, Friedrich says: Is it delicious? Does it fill me up? Is it reasonably priced?

Fermentation is a booming sector in the alternative protein industry. It is split into three categories: traditional fermentation using lactic acid bacteria, yeasts or fungi; biomass fermentation which involves naturally occurring, protein-dense, fast-growing microorganisms; and precision fermentation, which uses microbial hosts as “cell factories” to produce specific ingredients.

Data from GFI found, of the alt protein startups utilizing fermentation, 45% use precision fermentation, 41% use biomass fermentation and the remaining 14% use traditional fermentation.

GFI recently hired two fermentation scientists, and their studies are already suggesting biomass and traditional fermentation will have better environmental numbers than plant-based meats. Fermentation is also a more powerful process than plant-based meat applications because fermentation can replicate precise fermentation proteins. And although traditional fermentation is the smallest part of the fermented alternative protein category, GFI sees it growing because of its ability to produce appealing flavors..

“Traditional fermentation can be an absolutely essential element to get meat to taste the same or better or cost the same or less,” he says.

“The plant based and fermentation products, they’re just getting started. The idea of competing with industrial animal meat has been around for (snaps his fingers) that long. The products are just going to improve and improve and improve.”

The New Funk

Have you tasted furu yet? More Asian American chefs are using the fermented tofu.

Common in Chinese and Taiwanese cuisine, furu is made by soaking soybean curbs in a brine of rice wine, water, salt and spices. The flavor has a “specific tang, mild sweetness and intense umami,” according to a New York Times article.

“Furu adds a ton of funk that you can’t get from anything else,” says Calvin Eng, owner of the Cantonese American restaurant Bonnie’s in Brooklyn, New York. The restaurant’s dish furu cacio e pepe mein is noodles in the fermented bean curd.

Read more (The New York Times)

- Published in Food & Flavor

Cultured in Chicago: Highlights of FERMENTATION 2022

Science met the culinary arts in Chicago, at the first in-person conference of The Fermentation Association (TFA), FERMENTATION 2022. Over 200 food and beverage professionals from 15 countries Participated in four days of programming.

“There’s no denying that fermentation is having a moment – and that’s a wonderful thing that more and more people are aware of fermentation and interested in fermentation – but it’s really important to keep saying fermentation is not a fad, fermentation is a fact,” said Sandor Katz, fermentation author and educator.

Katz was the opening keynote speaker at FERMENTATION 2022. The nearly 50 experts and thought leaders who presented included Dan Saladino (BBC journalist and author of Eating to Extinction), Kirsten Shockey (author, educator and co-founder of The Fermentation School), Bob Hutkins (food microbiology professor at University of Nebraska and founder of Synbiotic Health), Sharon Flynn (founder of The Fermentary in Melbourne, Australia), Bruce Friedrich (co-founder and executive director of The Good Food Institute), Maria Marco (food science professor at University of California, Davis) and Sean Brock (chef and owner of Nashville’s Audrey Restaurant).

The conference comes as sales of fermented foods and beverages continue to rise. Fermented products grew 7.1% in the last year, according to SPINS LLC, a data provider for natural, organic and specialty products that also presented at FERMENTATION 2022.

Though Katz taught his first fermentation workshop in 1998, he’s seen “a building interest in fermentation” in the last decade. Each year since 2011, “someone says the food trend of the year is fermentation.”

“Usually I end up being a cheerleader for fermentation, encouraging people who somehow think that fermentation is an alien process, that there’s something scary about it,” he said. “I mostly reassure people that they’ve been eating products of fermentation almost every day for their entire lives, that these are processes that their safety has been proven by their endurance over time. But you all don’t need to hear that. I am speaking to the converted here.”

Where Science Meets Industry

TFA aims to fill a niche in the world of fermentation. There are plenty of DIY fermentation festivals, food and beverage industry conferences and trade shows. But TFA connects science and industry.

Attendees at the event included an array of professionals involved in fermentation – producers, retailers, chefs, scientists, researchers, authors, suppliers, educators and regulators. The conference revolved around three tracks: food, flavor and culture; science and health; and business, legal and regulatory. The group of passionate fermenters in attendance uniformly expressed their excitement and delight to learn from experts in different disciplines.

“This unique conference had the most diverse attendees as it included chefs, scientists and more,” said Glory Bui, a graduate student researcher at the University of California, Davis. “It was nice to network with those who were and were not in academia to hear different perspectives in the fermentation industry.” [Bui won the student poster competition with her research on how fermented dairy products can affect gastrointestinal health.]

Producers made up over 40% of attendees and ran the gamut from small to large scale. Sash Sunday, founder and fermentationist behind OlyKraut in Olympia, Wash., said she’s been searching for such a fermentation conference since starting her brand in 2008.

“I really appreciate getting to spend time getting to know other fermenters, hearing about people’s creative processes and experiences in the field,” Sunday said. “I really loved all the tastings and spending time with people who really think about the flavors in fermented foods.”

Niccolo Fraschetti, owner of Alive Ferments, said networking was one of his favorite parts of the conference.

“There were people there that were superstars of fermentation to people making kimchi in the bathtub,” Fraschetti said. “It was such a cool merging of fermentation.”

Fraschetti officially launched Alive Ferments in March and said he never expected the brand to grow so fast, so quickly. Alive Ferments currently is sold in 25 stores in the San Diego area. At FERMENTATION 2022, he brainstormed ideas with attendees and speakers.

“Usually I feel like in these situations, everyone is tight-lipped and doesn’t want to share (business secrets),” he said. “But everyone was a really embracing community and willing to share their knowledge. There was no competition between the peers that were at the conference.”

Connecting with others in the industry was a highlight, too, for Suzette Smith, founder of Garden Goddess Ferments and Pick up the Beet in Arizona.

“I loved that like minds were able to come together sharing similar passions,” Smith said. (I also loved “learning what’s new in the promotion of fermented foods.”

Gregory Smith, an independent chef based in Pittsburgh, said he “drove back from Chicago with my mind racing about all the things I learned.” He said the various chefs who spoke at the conference – like Flynn, Brock, Ismail Samad of Wake Robin Foods, Jessica Alonzo of Native Ferments, Misti Norris of Petra and the Beast and Jeremy Kean of Brassica Kitchen – inspired him to dive into upcycling.

“I’m excited about the way they made me look at food waste in the kitchen space and how to help utilize waste and taking excess product and converting it into something tasty,” said Smith, who runs his independent culinary service Thyme, Love & Culture with friend Romeo Kihumbu.

Karen Wang Diggs, founder of the ChouAmi fermentation device, spoke at the event in a session on fermenting with medicinal plants. She said it was “an honor” to speak at FERMENTATION 2022.

“I got to hang out with a bunch of really cool, ‘cultured,’ fermenting people – and the presentations were fabulous,” she said.

Added Neal Vitale, executive director of The Fermentation Association: “It was a privilege to have a stellar lineup of speakers. It was great to get to get together at last and explore so many aspects of fermentation.”

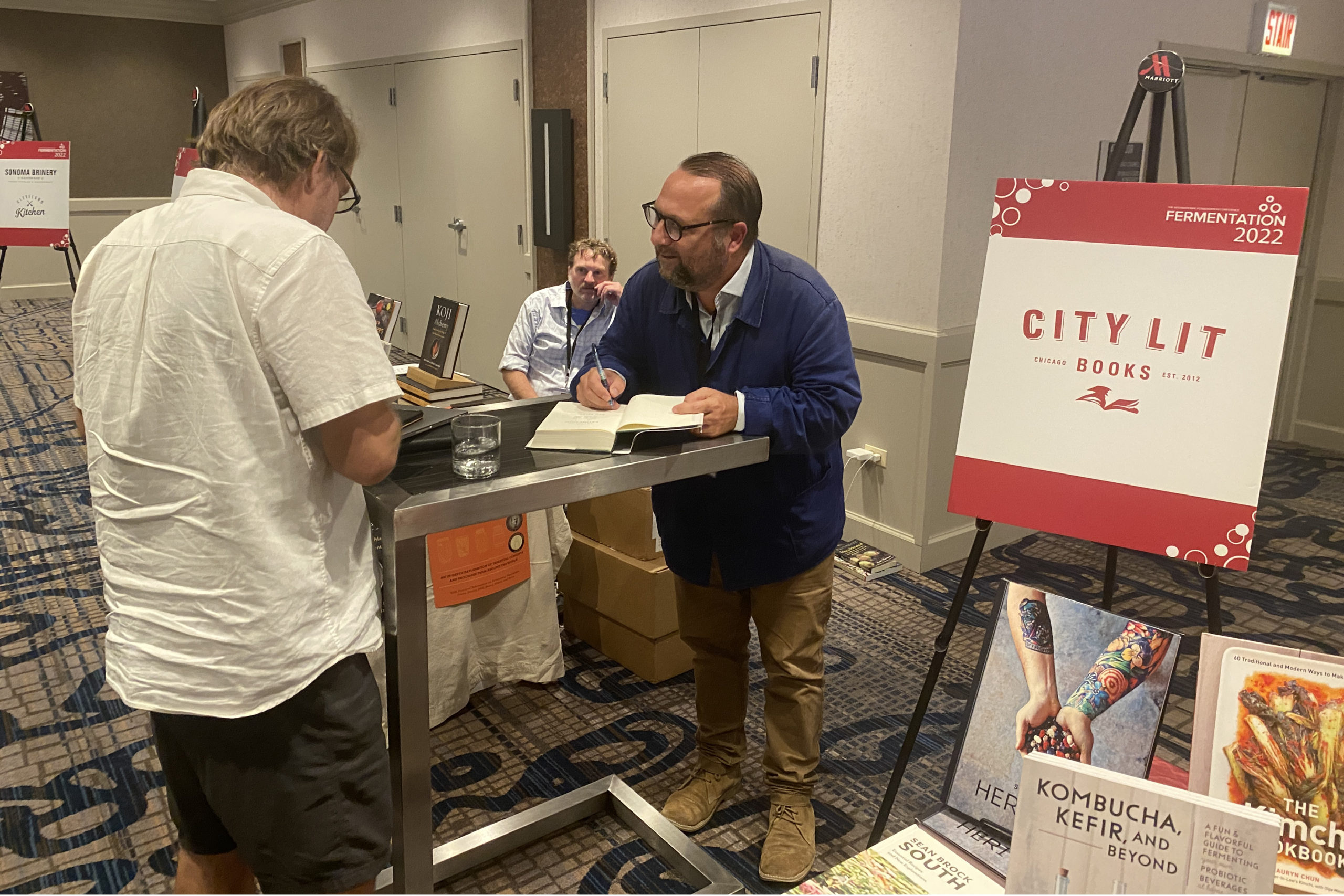

Focus on Food

Other events at the conference included: a dinner with a fermentation-focused menu prepared by Rick Bayless, chef and restaurateur; a mezcal tasting with Lou Bank, founder of SACRED and the Agave Road Trip podcast; a craft beer and chocolate pairing with Long Beach Beer, Bread and Spirits Lab; a flavor analysis workshop with Sensory Spectrum Inc.; a screening of Ed Lee’s film Fermented (complete with buttered popcorn!); and multiple book signings.

Bayless, the James Beard Award winner who runs multiple Chicago restaurants, mingled with conference attendees during the dinner. He said he and his staff enjoyed the challenge of putting something fermented in every course.

“This is the first time we’ve done a meal that is so heavily fermented,” he said, “and we had a lot of fun doing it.”

Courses included a fermented corn masa tamal, beed with a fermented black bean sauce made with black bean miso and Oaxacan pasilla chile, smoked yellowfin tuna in a broth of tejuino (fermented corn drink), and chocolate from Tabasco, Mexico, with tepache (fermented pineapple) sorbet .

“I was at a conference with Sandor Katz years ago and I talked to him about making black bean miso, and now I get to serve it to him,” Bayless said.

The Fermentation Association was started in 2017 as the brainchild ofJohn Gray, then the owner of Bubbies Pickles. His goal was simple – to bring together everyone in the world of fermentation. Today, TFA circulates its biweekly newsletter to nearly 14,000, is followed by over 11,000 on Instagram and will next develop its presence on LinkedIn. The Association is run by a small staff and a 22-member Advisory Board, including six Science Advisors.

FERMENTATION 2022 was originally planned to be a May 2020 event, but obviously postponed due to Covid-19. A virtual FERMENTATION 2021 was held in November 2021. TFA will announce plans for 2023 and beyond in the coming months.

- Published in Business, Food & Flavor, Health, Science

Chicago: A Fermentation Hub

If you still think of hot dogs and deep dish pizza as the icons of Chicago’s culinary scene, you need to think again. The so-called Capital of the Midwest is a hub of innovation in the food industry. Chicago has the largest food and beverage production in the U.S., with an annual output of $9.4 billion. Food startup companies in the region raised $723 million in venture capital last year.

“Chicago is one of the most diverse cities for eating,” says Anna Desai, Chicago-based influencer of Would You Like Something to Eat on Instagram. ”Our culinary scene is constantly elevating and evolving. We are always just a neighborhood or tollway away from experiencing a new culture and cuisine. I’m most excited when I find an under-the-radar spot or discover a maker who can pair flavors and ingredients that get you curious and wanting more.”

Desai started her blog in part because she wanted to champion the Asian American and Pacific Islanders (AAPI) community in the Chicago food and beverage scene. “Food has long served as a cultural crossroad,” she adds, and Chicago’s multicultural cuisine exemplifies that sentiment.

Chicago is home to some of the most creative minds in fermentation, from celebrity chefs, zero waste ventures, alternative protein corporations and the world’s largest commercial kefir producer. There are dozens of regional and artisanal producers lacto-fermenting vegetables, brewing kombucha and experimenting with microbes in food and drink.

“Chicago is a great food city in its own right, so naturally there is a ton of talent in the fermentation space,” says Sam Smithson, chef and culinary director of CultureBox, a Chicago-based fermentation subscription box. “The pandemic’s effect on restaurants has also spawned a new wave of fermenters (ourselves included) that are looking for a path outside the grueling and uncertain restaurant structure to display our creative efforts. This new wave is undoubtedly community-motivated and concerned more with mutual aid than competition. There is a general feeling that we are all working towards the same goal so cooperation and collaboration is soaring and we are seeing incredible food come from that.”

Flavor is King

Flavor development is still the prime motivation for chefs to experiment with fermentation. A good example is at Heritage Restaurant and Caviar Bar in Chicago’s Humboldt Park neighborhood.

“Fermentation has been a cornerstone of the restaurant since its inception,” says Tiffany Meikle, co-owner of Heritage with her husband, Guy. “With the diverse cuisines we pull from, both from Eastern and Central Europe and East Asia, we researched fermentation methodologies and histories, and started to ‘connect the dots’ of each culture’s fermentation and pickling backgrounds.”

Menus have included sourdough dark Russian rye bread, toasted caraway sauerkraut, kimchi made from apples, Korean pears and beets and a kimchi using pickled ramps (wild onions). Heritage has also expanded their fermentation program to the bar, where they’ve created homemade kombucha, roasted pineapple tepache, sweet pickled fruits for cocktail garnishes, and kimchi-infused bloody mary mix.

“It’s fascinating to me that there are so many ingredients you can use in a fermented product,” says Claire Ridge, co-founder of Luna Bay Booch, a Chicago-based alcoholic kombucha producer. “People are really experimenting with interesting ingredients in kombucha…I have seen brewers do some of the wildest recipes and some recipes that are very basic.”

Innovating Food

Chicago-based Lifeway Kefir is indicative of the innovation taking place in the city. Last year the company expanded into a new space: oat-based fermentation, launching a dairy-free, cultured oat milk with live and active probiotics.

“We’ve spent so many years laying the groundwork in fermented dairy,” says Julie Smolyansky, CEO. “Now we’re experimenting and expanding to see what’s over the next horizon, though we’ll always have kefir as our first love.”

Chicago is home for two inventive fermented alternative protein startups: Nature’s Fynd and Hyfé Foods. Both companies were born out of the desire to create alt foods without damaging the environmental.

“Conscious consumerism is a trend that’s driving many people to try alternative proteins, and it’s not hard to understand why,” says Debbie Yaver, chief scientific officer at Nature’s Fynd. The company uses fermentation technology to grow Fy, a nutritional fungi protein. “Fungi as a source of protein offer a shortcut through the food chain because they don’t require the acres of land or water needed to support plant growth or animal grazing, making fungi-based protein more efficient to produce than other options.”

Alternative foods outlasting the typical trend cycle is a challenge for companies like Nature’s Fynd. When grown at scale, Fy uses 99% less land, 99% less water and emits 94% fewer greenhouse gasses than raising beef. But, to make an impact, “we need more than just vegans and vegetarians to make changes in their diets,” Yaver adds.

Waste Not

Numerous companies are using fermentation as a means to eliminate waste. Hyfé Foods, another player in the alternative protein space, repurposes sugar water from food production to create a low-carb, protein-rich flour. Fermentation turns a waste product into mycelium flour, mycelium being the root network – or hyphae (hence the company name) — of mushrooms.

“[We’re] diverting input to the landfill and reducing greenhouse gas emissions at scale,” says Michelle Ruiz, founder. “Hyfé operates at the intersection of climate and health, enabling regional production of low cost, alternative protein that reduces carbon emissions and is decoupled from agriculture.”

Symmetry Wood is another Chicago upcycler. They convert SCOBY from kombucha into a material, Pyrus, that resembles exotic wood. Founder Gabe Tavas says Pyrus has been used to produce guitar picks, jewelry and veneers. Symmetry uses the discarded SCOBY from local kombucha brand Kombuchade.

Many area restaurants and culinary brands also use fermentation to preserve food for the long Chicago winters, when local produce isn’t available. Pop-up restaurant Andare, for example, incorporates fermentation into classic Italian dishes.

“Finding ways to utilize what would otherwise be waste products inspired our initial dive into fermentation. The goal is not just to use what’s leftover, but to make it into something delicious and unique,” says Mo Scariano, Andare’s CEO. “One of our first dishes employing koji fermentation was a summer squash stuffed cappellacci served with a butter sauce made from carrot juice fermented with arborio rice koji. Living in a place with a short grow season, preservation through fermentation allowed us access throughout the year to ingredients we only have fresh for a few weeks during the summer.”

Industry Challenges

Despite growing interest and increasing sales, fermenters face some significant hurdles.

Smithson at CultureBox says he sees that consumers are open to unorthodox, less traditional ferments. Though favorites like kombucha and sauerkraut dominate the market, “their share is being encroached on by increasingly more varied and niche ferments.” But getting these products to market can be a challenge. Small-scale, culinary producers are challenged by the regulatory hoops they need to jump through to legally sell ferments – especially unusual ones a food inspector doesn’t recognize.

“The added layer of city regulations on top of state requirements, sluggish health department responses, and inflexible policy chill the potential of small producers,” Smithson says. But he highlights the recently-passed Home-to-Market Act of Illinois as positive legislation helping startup fermenters.

Consumer awareness and education are also vital. “Many longstanding and harmful misconceptions on the safety and value of fermented products still exist,” Smithson says.

Matt Lancor, founder and CEO of Kombuchade makes consumer education a core part of marketing, to align kombucha as a recovery drink.

“Most mainstream kombuchas are marketed towards the yoga/crystal/candle crowd, and I saw a major opportunity to create and market a product for the mainstream athletic community,” he says. “We’re on a mission to educate athletes and the general public about these newly discovered organs [the gut] – our second brain – and fuel the next generation of American athletes with thirst quenching, probiotic rich beverages.”

Product packaging provides much of a consumer’s education. Jack Joseph, founder and CEO of Komunity Kombucha, says simplicity is key.

“People are more conscious of their health now, more than ever before,” he says. “So now it comes down to the education of the product and creating something that is transparent and easy for the consumer to digest.”

Sebastian Vargo of Chicago-based Vargo Brother Ferments agrees.

“Oftentimes food is considered ‘safe’ due to lack of microbes and how sterile it is,” he says. “Fermentation eschews the traditional sense of what makes food ‘safe’. We need to create a set standardized guide for fermented food to follow, and change our view of living foods in general. One of the brightest spots to me is the fact that fermentation is really hitting its stride and finding its place in the modern world, and I don’t see it going anywhere but up in the near future.”

- Published in Business, Food & Flavor

Bubbling Over: Chicago Fermentation Scene

In anticipation for our conference FERMENTATION 2022 in Chicago, TFA asked over a dozen area fermenters about what they love about the city’s fermentation scene. Their answers touched on a number of points: creativity in foods and beverages, diverse offerings, scrappy and determined founders, supportive community and evolving foodscape.

Below are the answers from three local fermentation experts – kefir company founder Julie Smolyansky (Lifeway Kefir), local ferments producer Sebastian Vargo (Vargo Brother Ferments) and chief scientific officer Debbie Yaver, PhD (Nature’s Fynd).

The question: What do you love about the Chicago fermentation scene?

Julie Smolyansky, Lifeway Kefir

Chicago is a true melting pot. We have diversity, talent, and lots of skilled manufacturing talent. It’s one of the premier food cities in the world and I’m so grateful that we’ve been able to build our business and community in Chicago. The natural foods, fermentation, and dining scene all commingle to create opportunities for a special type of risk-taking that’s uniquely Chicago. Lots of it bubbles under the radar – who would have guessed that the kefir capital of the United States is in the Midwest?

Sebastian Vargo, Vargo Brother Ferments

I love the fact that we are seeing more fermentation than ever, from restaurants to store shelves to folks starting projects at home. I love the community behind it, folks are sharing recipes and exchanging tips and tricks. People don’t have time for gatekeeping anymore.

Debbie Yaver, Nature’s Fynd

I love that it flips the script. For so long Chicago was known as the “Hog Butcher to the World,” but now one of the oldest technologies in the books is experiencing a renaissance. There are lots of companies utilizing traditional fermentation, but not as many in the food space. It’s exciting to be one of the newer kids on the block, to see how different companies are putting fermentation to work, and to get to pull from such a stocked talent pool. Chicago is full of bright minds with deep fermentation experience.

- Published in Food & Flavor

Will Fermentation Connect Gastronomy and Biotech?

Fermentation is motivating scientists to listen to gastronomers, a rare occurrence in the field of science.

“There’s going to be a huge exchange in this two-way road that we’re living in. Innovation in flavor coming from gastronomy and innovation coming from a high-level biotechnology, they are going to be harmonious,” says Jason White, director of the fermentation lab at Noma in Copenhagen. “We’re going to be able to create this infrastructure and community of people who have the same goal, and the same goal is going to be the wellness of our planet.”

White spoke at the 2nd international Food Innovation Conference. This annual gathering of industry experts is produced by the Gottlieb Duttweiler Institute (GDI), Switzerland’s oldest independent think tank, which researches the future of food, retail and health.

The conference focused on the future of fermented alternative proteins. Or, as GDI puts it: “how innovation can solve the carnivore conundrum.” Speakers included the founders of numerous precision fermentation companies, such as SuperBrewed Food, Bosque Foods, Melt&Marble and WNWN Food Labs.

“We do the same thing, we just have different outputs”

Fermentation for alternative proteins is a divisive topic among traditional fermenters. Many say it’s lab-created fake food. Advocates, though, argue precision fermentation using DNA from mammals (as with Impossible Foods’ heme protein burger) and biomass fermentation of fast-growing, naturally-occurring organisms(e.g., Nature’s Fynd fungi protein) are reducing the risk of a global food crisis. Meat consumption is increasing, but animal meat is environmentally inefficient to raise. The significant amounts of agricultural land, fertilizer, pesticide and hormones needed to raise animals for meat protein release harmful carbon emissions.

The chefs on GDI’s “Fermentation: A World Within Gastronomy” panel spoke favorably of using fermentation for alt foods. White was joined by Ezio Bertorelli, co-founder of fermentation shop Meta Copenhagen, and Sirkka Hammer, founder of food manufacturer Wiener Miso in Austria.

“I think that it’s important for us not to steer too far away from the origins of fermentation,” White notes. But, “whether you have this bioreactor filled with whatever working inside of a laboratory with a team of scientists, we are still creating something that comes from microorganisms and from organisms. And so we do the same thing, we just have different outputs, different audiences.”

Precision fermentation technology is rooted in traditional fermentation, he notes. You need to understand the abilities of microbes and composition of ingredients for a successful precision fermentation.

“Inside of these laboratories and restaurants, there’s so many things that are being discovered that stop at the guest experience,” White says of fermentation. Today, as fermentation continues a revitalization as a kitchen craft, it’s utilized by more people rather than just chefs and scientists.

DIscovering Fermentation

Hammer highlighted the boom in home fermentation, with people creating the bold flavors of fermented foods and beverages on their own countertops.

“There’s a certain magic in fermentation. That’s why you’re gripped with it,” she says. “People are bringing a little bit of that magic, uncontrollable magic maybe [into their homes].”

At Wiener Miso, Hammer launched the company’s umami-driven ferments after living in Asia for more than a decade. The spices, pastes and sauces she makes are based on traditional Japanese ferments.

“Fermenting gives you in gastronomy next level or an add-on of flavors and textures,” she says. “Fermentation really changes the texture in a different way than if you cook it or freeze it. It gives it new dimensions.”

Flavor is what introduced Bertorelli to fermentation, too. His background is in professional cooking – he is the former executive chef of La Petite Table in Paris – but he was always experimenting with miso and sauerkraut in his home kitchen.

Even today, his fermentation experiments “go terribly wrong most of the time,” says Bertorelli. Only about 5% are successes, “that’s what makes it exciting.”

“Fermentation really changed my life because it showed me most of the dishes I was passionate about, the origin of the flavor, was the fermented part,” he says. “Flavor is universal… If you have that mind-blowing moment, it can reconnect you with things that are inside all of us, like our ancestors have been eating these foods since thousands of years ago and it’s sort of like going back in time while still being here.”

- Published in Food & Flavor

The “Periodic Table” of Fermented Foods

A pioneering “periodic table” of fermented foods was released this month, the first attempt to represent the breadth and range of fermented foods and beverages in graphic form.

This creation is the brainchild of Michael Gänzle, PhD, professor and Canada Research Chair in Food Microbiology and Probiotics at the University of Alberta. Gänzle is regarded as an expert in fermented foods and lactic acid bacteria. His recent research includes identifying a new taxonomy for the lactobacillus genus, a topic Gänzle spoke about in a TFA webinar.

“Non-traditional fermented foods are a big trend both in industrial food production and in culinary arts,” Gänzle said in an interview with TFA. “The periodic table may be the most concise overview on what is possible if all of the diversity of our benign and beneficial microbial helpers is recruited.”

The impetus for the table dates to 2014, when Gänzle and a colleague used a periodic table of beer styles in their food fermentation class. They wondered if it would be feasible to create a similar version for fermented foods.

Gänzle’s final version, along with his well-documented analysis of the table, was published in the journal Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. The table includes 118 entries of fermented foods, each coded for product category, country of origin, fermentation organism (like LAB, acetic acid bacteria or yeasts), fermentation substrate, metabolites and fermentation time.

Gänzle suggests the table is “quite useful for a number of things that may impact the development of fermented foods.” He says fermentation has “reemerged as a method to provide high-quality food.” A chef or producer can use the table to compare “differences and similarities in the assembly of microbial communities in different fermentations, differences in the global preferences for food fermentation, the link between microbial diversity, fermentation time and product properties, and opportunities of using traditional food fermentations as templates for development of new products.”

Because of its straightforward graphical layout, the table can quickly answer questions. A scan of it shows “which foods contain live fermentation microbes, which regions of the world have which preferences for substrates and fermented foods, which fermented foods are back-slopped and are fermented with host-adapted fermentation organisms.”

He stresses, though, that the table has its limitations, as it doesn’t cover every fermented food.

“The more I read the more likely I am to quote Plato’s rendition of Socrates’ statement that ‘I neither know nor think I know,’” Gänzle says. “Fermented foods are about as diverse as humankind.”

Gänzle plans to continue to revise the table on his personal website. Currently, he and two doctoral students are researching fermented soy and legumes, so look for the next updates to be in those categories.

- Published in Science

The State of Fermentation Education

The Covid-19 lockdown spurred aspiring home chefs around the world to try fermenting for the first time. DIY classes moved virtual and countertops filled with bubbling crocks of kimchi, sauerkraut, kombucha and sourdough. Fermentation was one of the top pandemic hobbies.

For professional fermentation educators, this trend brought new, eager faces to classes. But now, as lockdown restrictions have eased, are people still wanting to experiment making their own microbe-rich food?

We asked three experts to share their thoughts on the current state of fermentation education — author and educator Kirsten Shockey (of The Fermentation School and Ferment Works), writer and educator Soirée-Leone (who can be found via her website) and chef, food scientist and fermentation educator Jori Jayne Emde (of Lady Jayne’s Alchemy and The Fermentation School). [Shockey and Soirée-Leone are both members of TFA’s Advisory Board.]

The question: What is the current state of fermentation education?

Kirsten Shockey, author and educator

Fermentation education is exploding. The time has never been better. The interest in fermentation — both as a topic and in hands-on engagement — keeps gaining momentum. People are both more curious and more confused than I have seen in the past. I think part of that is because with the boom of interest a lot of people are coming forward as experts sharing content without the prerequisites to inform accurately. For example, we see misinformation about the subtle differences in fermentation vs. culturing vs. pickling that end up leaving people who are just dipping their toes in the process a little less unsure. When these folx do engage with true experts they are enthusiastic students who enjoy soaking up all that they can and we see their anxieties dissipate. I speak from the experience of working with solid experts and their students through The Fermentation School. It has been beyond gratifying to work with an amazing group of really talented fermentation educators to grow quality online education and a dedicated “help” community through The Fermentation School. In my other educator hat, as an author, it is less clear to me how that media is working for education, but that is a bigger issue in that the publishing world itself is in a lot of flux.

Soirée-Leone, writer and educator

Folks are connecting with familial, cultural, and traditional roots through fermentation. They are building online communities to share knowledge, taking workshops, participating in residencies, checking books out from libraries, and attending fermentation festivals that are popping up all over the world.

While there is an abundance of information available through books and websites, some folks seek to connect in person through workshops. I find that it’s especially dynamic to teach and learn in collaborative environments to share skills and experiences. There are so many traditions, techniques, and riffs. It is exciting to learn about folks’ travels, study, and experiments — we each have a different fermentation journey and something to teach and learn.

Today is a far cry from when I first started cheesemaking in 1991 with one slim book that sang the praises of junket rennet. Now there are books sharing natural cheesemaking techniques, bloggers happy to answer questions, travelers bringing information home and sharing online, and workshops to attend.

Fermentation is accessible with rudimentary kitchen equipment and improvised incubators and cheese caves. Fermentation is empowering and engaging of all our senses—and learning new things about fermentation is a never-ending journey.

Jori Jayne Emde, chef, food scientist, fermentation educator

My perspective on this is it’s booming! There was a huge burst of interest for online learning during the pandemic, and I have not seen that slow down much. Fermentation is a trendy topic and word with, unfortunately, a tremendous amount of misinformation floating around out there. It’s an important time as an educator to really remain engaged with students, as well as capturing fermentation aspirants, guiding them towards proper and well informed education taught by experts in the field of fermentation and health.

- Published in Food & Flavor

Zero Waste with Fermentation Techniques

Paste Magazine highlights the fermentation philosophy of Chef David Porras, who operates the Oak Hill Café and Farm. The hyper-local site, a 2020 James Beard semi-finalist for Best New Restaurant, operates in Greenville, South Carolina, on a 2.4-acre farm.

Porras’ kitchen, according to the magazine, “looks like an alchemist’s workroom, jars and tubs of experimental pickling, emulsions and infusions dotting the counter.”

“I was always interested in learning about fermentation. Fermentation is a flavor — you can use it for cooking just like lime or lemon juice,” he said.

The restaurant’s menu reflects a true farm-to-table approach. They use permaculture (sustainable agriculture planning to mimic nature) to keep the farm at peak fertility to grow healthy produce. By fermenting instead of trashing unused food, they’ve reduced 50% of their food waste.

“We try to be zero waste by applying fermentation techniques as well as drying, infusion, teas, powders and compost tea,” he said.

Read more (Paste Magazine)

- Published in Food & Flavor