The Trending Nordic Diet

For nearly two decades, the Mediterranean diet has been the food choice recommended by dietitians and the USDA.. This approach to eating has been proven to improve health and reduce risk of chronic disease.

But there’s a new contender: the Nordic diet.

This plan focuses on eating fermented foods and beverages, with less meat and more legumes than in the Mediterranean diet. Both approaches are plant-based and full of lean proteins, complex carbs and healthy fats.

“The nordic diet really does promote a lifelong approach to healthy eating,” says Valerie Agyeman, RDN (pictured). “It also really really focuses on seasonal, local, organic and sustainably sourced whole foods that are traditionally eaten in the Nordic region.”

Agyeman, founder of Flourish Heights, shared her research during a Today’s Dietitian webinar “Breaking Down the Nordic Diet: Why is it Gaining So Much Popularity?” The presentation was designed to help registered dietitians better counsel clients on healthy eating habits.

What is Nordic Eating?

The diet embraces traditional Nordic cuisine, with a focus on ingredients that are fresh and local. The core of the fare is from Sweden, Norway, Denmark, Finland and Iceland.

“Fresh, pure and earthly are the words used to describe this food movement that was born out of the landscape and culture,” Agyeman says. “The Nordic movement is all about using what is available.”

The goal is not to invent a new cuisine, but to get back to its roots. Seafood is central, but meat – scarce during the long Nordic winters – is treated as a side dish Fresh vegetables and berries – the most common Nordic fruit – are prevalent during the summer. Fermented foods were born out of the necessity to preserve food from the warmer months to eat during winter. The indigenous Nordic people traditionally fermented vegetables, fish and dairy.

“It really takes the focus off calories and puts it on healthy food,” Agyeman adds. “This way of eating is pretty nutrient-dense.”

Nordic foods, she continues, are served in their natural state with minimal processing. They’re high in antioxidants, prebiotics, probiotics, fiber, minerals and vitamins; low in saturated fats, trans fats, added sugars and added salts.

“The Nordic diet is really not that straightforward,” Agyeman says. “When you think of other cuisines, like Italian cuisine, they have signature flavors and various culinary techniques that make up Italian cuisine. When it comes to Nordic cooking, it’s very diverse.”

Sustainability

Key, too, is sustainability. Foods from the Nordic countries have a lower environmental impact because they’re sourced locally and eaten in season.

Sustainability is also partly why Nordic cuisine has become a staple at many restaurants. The farm-to-table style continues to expand in restaurant dining, along with fermentation. Restaurants around the world are following the lead of Copenhagen’s Noma and building their own labs to explore the flavors and textures fermentation adds to dishes.

“Today [fermentation] is not something that’s needed,” like it was before a global food scene made it simpler to eat fresh food year round, Agyeman says. “But culinary wise, fermentation has evolved. It’s become a big part of these new creations.”

Fermented foods and beverages add to the “epicurean experience,” adds Dr. Luiza Petre, a cardiologist and nutrition expert based in New York.

“Savory flavors and fermented food with spices make it a culinary experience,” she says.

Health Benefits

Studies show eating the Nordic diet prevents obesity and reduces the risk of cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, high blood pressure and high cholesterol.

The health effects of the Nordic diet were always assumed to be solely due to weight loss. But results of the most recent study of the diet, published in the journal Clinical Nutrition in February, found the positive health effects are “irrespective of weight loss.”

“It’s surprising because most people believe that positive effects on blood sugar and cholesterol are solely due to weight loss. Here, we have found this not to be the case. Other mechanisms are also at play,” said Lars Ove Dragsted, of the University of Copenhagen’s Department of Nutrition, Exercise and Sports in a statement on the study.

The researchers from Denmark, Finland, Norway, Sweden and Iceland studied 200 people over 50 years of age with elevated BMI. All were at an increased risk of diabetes and cardiovascular disease. For six months, the group ate the Nordic diet while a control group ate their regular meals.

“The group that had been on the Nordic diet for six months became significantly healthier, with lower cholesterol levels, lower overall levels of both saturated and unsaturated fat in the blood, and better regulation of glucose, compared to the control group,” Dragsted said. “We kept the group on the Nordic diet weight stable, meaning that we asked them to eat more if they lost weight. Even without weight loss, we could see an improvement in their health.”

- Published in Health

Microbial Farmers

An article in Modern Farmer highlights “the new generation of microbial farmers,” scientists using microbes to replace chemical additives in food.

At Kingdom Supercultures, co-founders Ravi Sheth (pictured) and Kendall Dabaghi have developed natural microbial strains that mimic additives “instead of having a library of artificial chemicals.” Scientists at the company use machine learning to explore millions of “uncharacterized microbes that live inside fermented food. They extract microbial strains, merge them with other isolates and design what they call ‘supercultures.’”

The end results are healthier compounds with flavors, textures and functional properties similar to their artificial – and less healthy – counterparts. Since the company launched in 2020, they’ve made additives for plant-based cheese and yogurt, vegan personal care products and a vegan butter exclusive to Eleven Madison Park restaurant in New York.

Read more (Modern Farmer)

- Published in Business

“Bacterial Bully” Could Create Healthier & Tastier Fermented Foods

Microbiologists have long considered that there are two distinct categories of energy conservation in microorganisms: fermentation and respiration. Lactic acid bacteria (LAB) use fermentation, making it central to food and drink production and preservation since the dawn of man.

But researchers at the University of California, Davis, and Rice University discovered a LAB species that uses a hybrid metabolism, combining both fermentation and respiration.

“These are two very different things, to the extent that we classify bacteria as basically one or the other,” said Caroline Ajo-Franklin, a bioscientist at Rice University and co-author of the study. “There are examples of bacteria that can do both, but that’s like saying I can ride a bicycle or I can drive a car. You never do both at the same time.”

“What we discovered is a LAB that blends the two, like an organism that’s not warm- or cold-blooded but has features of both,” she said. “That’s the big surprise, because we didn’t know it was possible for an organism to blend these two distinct metabolisms.”

The species — lactiplantibacillus plantarum — is what scientists call a bacterial bully because it takes advantage of two distinct metabolic processes, according to a press release from Rice on the study. These systems were “not previously known to coexist to acquire the fuel they burn for energy.”

“Using this blended metabolism, lactic acid bacteria like L. plantarum grow better and do a faster job acidifying its environment,” said Maria Marco, a professor in the food science and technology department at UC Davis and the study’s co-author [and a TFA Science Advisor].

The discovery is significant for food and chemical production. New technologies that use LAB could now produce healthier and tastier ferments, minimize food waste and change the flavors and textures of fermented food.

“We may also find that this blended metabolism has benefits in other habitats, such as the digestive tract,” Marco said. “The ability to manipulate it could improve gut health.”

The study began with a puzzle: the realization that genes responsible for the electron transfer pathway in mainly respiratory organisms also appear in the LAB genome. “It was like finding the metabolic genes for a snake in a whale,” Ajo-Franklin said. “It didn’t make a lot of sense, and we thought, ‘We’ve got to figure this out.’”

While the Davis lab studied the genome, the team at Rice carried out fermentation experiments on kale.

“It wasn’t our first choice,” said Rice alumna and co-lead author Sara Tejedor-Sanz (now a senior scientific engineer in the Advanced Biofuels and Bioproducts Process Development Unit at Lawrence Berkeley National Lab).

“We performed some initial experiments with cabbage, since that’s a known fermented food — sauerkraut and kimchi — in which lactic acid bacteria are present,” she said. “But there were technical difficulties and it didn’t turn out so well. So we looked for another food to ferment where LAB could be found in its ecological niches.

“Kale has compounds like vitamins and quinones that lactic acid bacteria use as cofactors in their metabolism, and are also involved in interacting with the electrodes,” she said. “We also found fermenting kale to make juice was a trend. It sounded perfect for our biochemical reactors.”

The study showed LAB enhances metabolism through a FLavin-based Extracellular Electron Transfer (FLEET) pathway that expresses two genes (ndh-2 and pp1A) associated with iron reduction, a step in the process of stripping and incorporating electrons into ATP (adenosine triphosphate (ATP), energy-carrying molecule).

Because LAB’s genome has evolved to be small, thus requiring less energy to maintain, the wide conservation of FLEET must serve a purpose, Ajo-Franklin said.

“Our hypothesis is this helps bacteria get established in new environments,” she said. “It’s a way to kick-start their metabolisms and outcompete their neighbors by changing the environment to be more acidic. It’s being a bully.”

That the FLEET pathway can be triggered with electrodes offers many possibilities, she said. “We found we can use the hybrid metabolism in food fermentation,” Ajo-Franklin said. “Now we have a way to change how food may taste and avoid failed food fermentations by using electronics.”

“We may also find that this blended metabolism has benefits in other habitats, such as the digestive tract,” Marco said. “The ability to manipulate it could improve gut health.”

Ajo-Franklin noted LAB are commonly found in the microbiomes of many organisms, including humans. “You can already buy it in health food stores as a probiotic,” she said. “The human gut is an anaerobic environment, so LAB have to keep a redox balance. If it oxidizes carbon to gain energy, it has to figure out a way to reduce carbon somewhere else.

“Now we think if we provide another electron donor or acceptor, we could promote the growth of positive bacteria over negative bacteria.”

UC Davis graduate student Eric Stevens is co-lead author of the study. Co-authors are Rice graduate student Siliang Li; at UC Davis, graduate students Peter Finnegan and James Nelson, and Andre Knoesen, a professor of electrical and computer engineering, at UC Davis; and Samuel Light, the Neubauer Family Assistant Professor of Microbiology at the University of Chicago.

Ajo-Franklin is a professor of biosciences and a CPRIT Scholar. Marco is a professor of food science and technology.

The National Science Foundation, Office of Naval Research, the Department of Energy Office of Basic Energy Sciences and a Rodgers University fellowship supported the research.

The study results were published in the journal eLife.

- Published in Food & Flavor, Health, Science

Evidence of Fermented Health Benefits

We’re on the cusp of a new generation of health-promoting foods, foods that will harness the power of microbes present in fermented foods and beverages.

Paul Cotter, head of Food Bioscience Department at Teagasc Food Research Centre in Ireland, envisions a future system where fermented foods are made with strains having scientifically-proven health-promoting benefits. His lab is integrating microbiome and metabolic data and using DNA sequencing to drill down to specific health benefits.

“We’ve really only scratched the surface as to the real potential of all those different microbes and what they could be doing,” says Cotter, who is also the principal investigator with the APC Microbiome Ireland. “Whether a particular food is health promoting or not will be dictated by what microbe is in there and can only be proved by carrying out the appropriate studies.”

Cotter was a speaker at TFA’s conference FERMENTATION 2021. He made a case for establishing minimum standards for fermented foods and beverages. In his scenario, kombucha or kefir couldn’t be labeled as such without using a scientifically-backed combination of microbial strains.

“That ensures that the kind of pseudo fermented foods — the foods that are fermented but not really with the right microbes — don’t get on the market or can’t be distinguished,” Cotter says.

Not all Fermented Foods are Equal

There is scientific evidence of the health benefits of frequently and regularly consuming fermented foods and beverages. They can prevent illness, provide a source of live and active microbes, improve the digestibility of foods, increase certain vitamins and bioactive compounds and remove or reduce toxic compounds like lactose.

“Ultimately, I’m a scientist and so I want to see proof that underpins the claims associated with a particular food,” Cotter says. “While there’s a lot of good information out there, I think also some of the claims are doing a disservice to the fermented food industry and to those who make fermented foods in their homes because they’re overstating the potential health benefits.”

Problematic, too, are fermented foods made with shortcuts and additives. Cotter’s lab is currently studying kefir, and they found that not all are equal. Traditional kefir has been documented as helping to reduce weight and improve cholesterol and liver triglyceride levels. But some brands of commercial kefir they studied didn’t produce those same health benefits. And they found that some of the kefir on the market was nothing more than watered-down yogurt.

“Consumer beware: the benefits weren’t the same for each kefir and differ depending on what the microbes present in the kefir were,” says Cotter, a self-described fermented foods nerd. ”I think that’s a problem for lots of other fermented foods too, and I really feel for consumers who don’t have a microbiological background and are reading a label and assuming that they are consuming a fermented beverage or fermented food that has lots of beneficial microbes in there and is made in the artisanal way that that food has been made over hundreds of different years.”

What are the health benefits?

Cotter’s lab has used in-depth analyses to detail the microbial composition of a food, including naming the microorganisms present and their capabilities. They’ve identified “completely novel species that had never been found previously,” Cotter says. An example is African fermented food, which contains a huge diversity of microbes, including ones not typically found in fermented foods in the West.

The highest level of what’s called “Health Associated Gene Clusters” are in fermented foods, specifically those brine- (like sauerkraut and kimchi) or sugar-based (kefir and kombucha). Cotter notes the genes in fermented foods are health promoting because the microbes are closely related to probiotics.

“What we can do is to try to harness the microbes that are present and use them in a way that facilitates large-scale production,” Cotter says.

Covid & the 4k’s: 4 Foods “Many People Don’t Know About”

Renowned professor, epidemiologist and author of The Diet Myth and Spoon Fed Tim Spector is encouraging people to eat the 4k’s: kefir, kombucha, kimchi and kraut. His studies found diet plays a role in preventing severe symptoms of Covid.

Spector is a leading expert on long Covid, the symptoms that can continue for extended periods after an initial infection. He leads the ZOE Covid Study, created by scientists and doctors at King’s College London (where he is based), Stanford, Harvard, Massachusetts General Hospital and health science company ZOE. Last year Spector helped research the attributes and predictors of long Covid, the results of which were published in the journal Nature Medicine.

A microbiome researcher, Spector advocates for people to eat a diverse diet to improve the trillions of microbes in the gut.

“We know from Covid now that your gut health is crucial for your immune system,” he told ITV. “If we can focus on our gut health…gut microbiome is really crucial.”

Diet must be high-quality to improve immunity, he stresses. In the ZOE Covid study, researchers have found eating “the right things and avoiding feeding (the gut) the bad things, that’s what made the difference to getting long Covid,” he said. Fermented foods have proven health benefits, but Spector says many people opt for cheaply-made yogurts and cheeses prevalent in the grocery store to get their daily dose of fermented foods. This dairy is full of sugar and artificial ingredients, which thwart the positive effects of fermentation.

“The other fermented foods that many people don’t know about are what I call the 4 k’s,” Spector says: kefir, kombucha, kimchi and kraut (sauerkraut). He encourages “small shots a day” of a fermented food or beverage. “That really is a powerful enhancer of your microbes. And all these things are going to be cheaper actually than taking multivitamins every day of your life.”

Spector is not a fan of supplements, like pill forms of vitamins and nutrients. Many are proven not to work, he explained. In his studies on the effects of supplements on long Covid, there were minimal benefits for women and none for men.

“People are much better off getting all their vitamins and nutrients by having a diverse diet,” Spector said.

- Published in Food & Flavor, Science

World’s Rarest Foods in Danger of Extinction

Journalist Dan Saladino explores the world’s endangered foods in his new book Eating to Extinction: The World’s Rarest Foods and Why We Need to Save Them. He argues that the world could lose culinary diversity. “The story of these foods, and the way in which they’re presented in the book,” says Saladino, from wild foods associated with hunters and gathers, to cereals, vegetables, meats and more, “is really the story of us and our own evolution.”

A review of Saladino’s book in Smithsonian Magazine shares 10 of the world’s rarest foods — five of them fermented. These rarities include:

- Skerpikjøt (Faroe Islands, Denmark): Dried and fermented mutton made from the shanks and legs of sheep. It ferments in wooden sheds called hjallur, which have vertical slats that allow space for the salty sea wind to blow in.

- Salers cheese (Auvergne, France): One of the world’s oldest raw milk cheeses made from the milk of Salers cows. The semi-hard cheese is made with varying fermentation lengths, which change the flavor.

- Qvevri wine (Georgia): Winemakers fill the egg-shaped terracotta pots called qvevri with grape juice, skins and stalks, then bury the pots underground. The steady temperatures and the pot’s shape allows even fermentation.

- Ancient Forest Pu-Erh Tea (Xishuangbanna, China): The fermented tea is made from wild tea leaves that grow in China’s southwestern Yunnan province. The leaves are sun-dried, cooked, kneaded, then formed into solid cakes and fermented for months (or years).

- Criollo Cacao (Cumanacoa, Venezuela): The world’s rarest type of cacao, it represents less than 5% of the cocoa production on the planet. The bean lacks bitterness, but is difficult to grow.

Read more (Smithsonian Magazine)

- Published in Food & Flavor

“So Stinky, Delicious, Irresistible”

“It’s fermented. It’s stinky. It’s delicious. And during the pandemic, it’s become a national sensation.”

Luosifen — snail noodles — is the subject of NPR’s latest All Things Considered program. The Chinese dish is made with rice noodles soaked in a broth of peeled river snails. It’s then topped with tofu, lemon vinegar and bamboo shoots (which have been covered in salt and fermented for a few weeks).

“Much of the preparation relies on fermentation, common in cuisine from southern Guangxi province where the noodles first began,” the NPR piece continues. “Their malodorous reputation also makes snail noodles quite possibly one of the worst meals to make at home: The smell of the pickled toppings and the stewed snails can linger for hours.”

Social media stars began sharing about the “disgustingly good snack” in 2020 during the Covid-19 pandemic. As a result,over 1.1 billion packets of snail noodle home kits were sold last year. And the city in China where snail noodles originated 25,000 years ago — Liuzhou — is experiencing an economic boom, as the nationwide popularity brings new business to snail noodle food stands, factories and chain restaurants.

Read more (NPR)

- Published in Food & Flavor

The Rise of Fermented Foods and -Biotics

Microbes on our bodies outnumber our human cells. Can we improve our health using microbes?

“(Humans) are minuscule compared to the genetic content of our microbiomes,” says Maria Marco, PhD, professor of food science at the University of California, Davis (and a TFA Advisory Board Member). “We now have a much better handle that microbes are good for us.”

Marco was a featured speaker at an Institute for the Advancement of Food and Nutrition Sciences (IAFNS) webinar, “What’s What?! Probiotics, Postbiotics, Prebiotics, Synbiotics and Fermented Foods.” Also speaking was Karen Scott, PhD, professor at University of Aberdeen, Scotland, and co-director of the university’s Centre for Bacteria in Health and Disease.

While probiotic-containing foods and supplements have been around for decades – or, in the case of fermented foods, tens of thousands of years – they have become more common recently . But “as the terms relevant to this space proliferate, so does confusion,” states IAFNS.

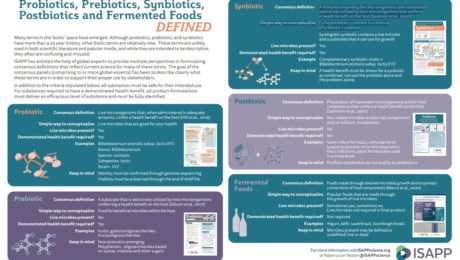

Using definitions created by the International Scientific Association for Postbiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP), Marco and Scott presented the attributes of fermented foods, probiotics, prebiotics, synbiotics and postbiotics.

The majority of microbes in the human body are in the digestive tract, Marco notes: “We have frankly very few ways we can direct them towards what we need for sustaining our health and well being.” Humans can’t control age or genetics and have little impact over environmental factors.

What we can control, though, are the kinds of foods, beverages and supplements we consume.

Fermented Foods

It’s estimated that one third of the human diet globally is made up of fermented foods. But this is a diverse category that shares one common element: “Fermented foods are made by microbes,” Marco adds. “You can’t have a fermented food without a microbe.”

This distinction separates true fermented foods from those that look fermented but don’t have microbes involved. Quick pickles or cucumbers soaked in a vinegar brine, for example, are not fermented. And there are fermented foods that originally contained live microbes, but where those microbes are killed during production — in sourdough bread, shelf-stable pickles and veggies, sausage, soy sauce, vinegar, wine, most beers, coffee and chocolate. Fermented foods that contain live, viable microbes include yogurt, kefir, most cheeses, natto, tempeh, kimchi, dry fermented sausages, most kombuchas and some beers.

“There’s confusion among scientists and the public about what is a fermented food,” Marco says.

Fermented foods provide health benefits by transforming food ingredients, synthesizing nutrients and providing live microbes.There is some evidence they aid digestive health (kefir, sourdough), improve mood and behavior (wine, beer, coffee), reduce inflammatory bowel syndrome (sauerkraut, sourdough), aid weight loss and fight obesity (yogurt, kimchi), and enhance immunity (kimchi, yogurt), bone health (yogurt, kefir, natto) and the cardiovascular system (yogurt, cheese, coffee, wine, beer, vinegar). But there are only a few studies on humans that have examined these topics. More studies of fermented foods are needed to document and prove these benefits.

Probiotics

Probiotics, on the other hand, have clinical evidence documenting their health benefits. “We know probiotics improve human health,” Marco says.

The concept of probiotics dates back to the early 20th century, but the word “probiotic” has now become a household term. Most scientific studies involving probiotics look at their benefit to the digestive tract, but new research is examining their impact on the respiratory system and in aiding vaginal health.

Probiotics are different from fermented foods because they are defined at the strain level and their genomic sequence is known, Marco adds. Probiotics should be alive at the time of consumption in order to provide a health benefit.

Postbiotics

Postbiotics are dead microorganisms. It is a relatively new term — also referred to as parabiotics, non-viable probiotics, heat-killed probiotics and tyndallized probiotics — and there’s emerging research around the health benefits of consuming these inanimate cells.

“I think we’ll be seeing a lot more attention to this concept as we begin to understand how probiotics work and gut microbiomes work and the specific compounds needed to modulate our health,” according to Marco.

Prebiotics

Prebiotics are, according to ISAPP, “A substrate selectively utilized by host microorganisms conferring a health benefit on the host.”

“It basically means a food source for microorganisms that live in or on a source,” Scott says. “But any candidate for a prebiotic must confer a health benefit.”

Prebiotics are not processed in the small intestine. They reach the large intestine undigested, where they serve as nutrients for beneficial microorganisms in our gut microbiome.

Synbiotics

Synbiotics are mixtures of probiotics and prebiotics and stimulate a host’s resident bacteria. They are composed of live microorganisms and substrates that demonstrate a health benefit when combined.

Scott notes that, in human trials with probiotics, none of the currently recognized probiotic species (like lactobacilli and bifidobacteria) appear in fecal samples existing probiotics.

“There must be something missing in what we’re doing in this field,” she says. “We need new probiotics. I’m not saying existing probiotics don’t work or we shouldn’t use them. But I think that now that we have the potential to develop new probiotics, they might be even better than what we have now.”

She sees great potential in this new class of -biotics.

Both Scott and Marco encouraged nutritionists to work with clients on first improving their diets before adding supplements. The -biotics stimulate what’s in the gut, so a diverse diet is the best starting point.

The Regulatory Landscape

Collaboration with regulators, not confrontation, is the recommended course of action for fermenters, experts suggest.

“Producers are speaking one language and regulators are speaking another,” says Abigail Snyder, assistant professor of microbial food safety at Cornell University. “Producers are like ‘Hey, this has been produced forever and it has a history of safe production!’ That’s not super meaningful for regulators. Regulators are used to this codified framework that is not necessarily built around fermented foods. There’s a middle ground.”

Snyder spoke with a panel of experts on health and safety regulations during TFA’s conference, FERMENTATION 2021. The consensus: food regulations exist to protect the consumer, but complying with myriad national, state and local laws can be difficult and frustrating to navigate, especially for a fermented food or beverage that utilizes novel food processes.

“Don’t be afraid, don’t feel like you’re going to tick off the inspector,” says Adam Inman, assistant program manager for the Kansas Department of Agriculture Food Safety & Lodging Program. He advises producers to always ask regulators for help. “Even if we start with your recipe and your process and we just document that, that can go a long way as a starting point.”

Jonathan Wheeler, coordinator for special processes at retail for the South Carolina Department of Health & Environmental Control, says if you’re dealing with a regulator unfamiliar with fermentation, ask for a supervisor. Wheeler manages South Carolina’s team of 80-90 regulators and points out that a health inspection should be an education opportunity for the regulator, too.

“We are partners on the same team, just in different roles,” Wheeler says. “Our approach in South Carolina has been driven by the need to educate as well as regulate. You have a voice, it’s part of collaboration and inspectors…are open to input [from producers].”

Still, compliance is not without its challenges.

Soirée-Leone, writer, homesteader and local food advocate, says that food inspection is one of the biggest challenges for smaller producers — especially in rural areas, where resources can be limited. For example, in Tennessee where she lives, home-based food businesses can sell their goods at farmers markets, as long as those items don’t need to be refrigerated. But there’s no rule for food that needs to be frozen,, so producers are allowed by the health department to sell popsicles.

“It’s very challenging, and a lot of people get very frustrated in the process,” she says.

Erin Leigh DiCaprio, assistant professor of cooperative extension at University of California, Davis, notes that regulations differ from state to state — a ferment produced under cottage food laws in one state could need a processed food license in another. She points out every state or county has an extension educator like herself who has the needed technical expertise to work with producers and regulators. DiCaprio specifically works with smaller-scale processors to navigate regulations in California.

Could the U.S. learn from other countries?In Korea, Japan and China, fermented foods and drinks are common, yet regulations are minimal.

“There’s a cultural aspect there… not necessarily advocating eliminating regulations but saying that a culture — and no pun intended in this case — but a culture that’s been used to eating fermented foods for years and had no negative impact. Is there some education to be learned from that?” questions Neal Vitale, the moderator and executive director of TFA.

“We should not be as regulators in a position of trying to jam fermentation processes… into a mold where they all look the same — because they don’t,” Wheeler says. “Educate me as how you want that process to look.”

- Published in Business

Definition & History of Fermentation

“Human civilization simply would not have been possible without fermented foods and beverages…we’re here today because fermented foods have been popular for humans for at least 10,000 years,” says Bob Hutkins, professor of food science at the University of Nebraska (and a recent addition to TFA’s Advisory Board).

Hutkins was the opening keynote speaker at FERMENTATION 2021, The Fermentation Association’s first international conference. His presentation explored the history, definition and health benefits of fermented foods.

Cultured History

The topic of fermentation extends to evolution, archaeology, science and even the larger food industry.

“The discipline of microbiology began with fermentation, all the early microbiologists studied fermentation,” Hutkins says.

Louis Pasteur patented his eponymous process, developed to improve the quality of wine at Napoleon III’s request. The microbes studied back then — lactococcus, lactobacillus and saccharomyces — remain the most studied strains.

“What interested those early microbiologists — namely how to improve food and beverage fermentation, how to improve their productivity, their nutrition — are the very same things that interest 21st century fermentation scientists,” Hutkins says.

Hutkins is the author of one of the books considered gospel in the industry, “Microbiology and Technology of Fermented Foods.” He says that fermented foods defined the food industry. In its early days, it was small-scale, traditional food production that “we call a craft industry now.” At the time, food safety wasn’t recognized as a microbiological problem.

Today’s modern food industry manufactures on a large-scale in high throughput factories withmany automated processes. Food safety is a priority and highly regulated. And, thanks to developments in gene sequencing, many fermented products are made with starter cultures selected for their individual traits.

“But I would say that there’s been kind of a merging between these traditional and modern approaches to manufacturing fermented foods, where we’re all concerned about time sensitivity, excluding contaminants, making sure that we have consistent quality, safety is a vital concern and extensive culture knowledge,” Hutkins says.

Defining & Demystifying

Fermentation — “the original shelf-life foods” — is experiencing a major moment. “Fermented foods in 2021 check all the topics” of popular food genres: artisanal, local, organic, natural, healthy, flavorful, sustainable, entrepreneurial, innovative, hip and holistic. “They continue to be one of the most popular food categories,” Hutkins continues.

Interest in fermentation is reaching beyond scientists, to nutritionists and clinicians. But Hutkins says he’s still surprised to learn how many professionals don’t understand fermentation. To address the confusion, a panel of interdisciplinary scientists created a global definition of fermented foods in March 2021.

“Fermentation was defined with these kind of geeky terms that I don’t know that they mean very much to anybody,” he says.

The textbook biochemical definition of fermentation that a microbiologist learns in Biochemistry 101 doesn’t work for a nutritionist or clinician focusing on fermentation’s health benefits. The panel, which spent a year coming to a consensus, wanted a definition that would simply illustrate “raw food being converted by microbes into a fermented food.” The new definition, published in the the journal Nature and released in conjunction with the International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP), reads: “Foods made through desired microbial growth and enzymatic conversions of food components.”

Fermentation in 2022

Hutkins predicts 2022 will see more studies addressing whether there are clinical health benefits from eating fermented foods. The groundbreaking study on fermented foods at Stanford was important. It found that a diet high in fermented foods increases microbiome diversity, lowers inflammation, and improves immune response. But research like this is expensive, so randomized control trials are few.

Fermented foods could also make their way into dietary guidelines.

“Fermented foods, including those that contain live microbes, should be included as part of a healthy diet,” Hutkins says.

- Published in Food & Flavor, Science