Fermenting Wild Foods

Wild food expert Pascal Baudar says the fact that we can buy tomatoes in the store year round “is freaky.” We should be eating food in season, and we’re ignoring the plethora of sustainable cuisine available in nature, edible food hikers overlook and cities destroy.

“One of the things I started realizing doing foraging is it’s really about food preservation techniques,” says Baudar, author of four books on traditional food preservation. “As a forager, plants go through different phases, but I have to find a way to preserve it so I can still eat my plants in the winter.”

Baudar and Sandor Katz, author of multiple books on fermentation, shared an intimate stage at cookbook store Now Serving LA in Los Angeles to promote Baudar’s latest book, Wildcrafted Vinegars. The two rockstars of fermentation encouraged the crowd to connect with the resources around them.

The Foraging Craft

Baudar learned foraging as a child from his grandmother. He grew up in Belgium, France in a rural town of just 1,000 people. “I really enjoyed this connection with the environment and the forest,” he says. He wanted to study it more – but, at the time, the only books on the subject of foraging wild plants and living with the environment were about witchcraft. He studied fine art instead, eventually becoming a graphic designer.

Nervous about the much hyped Y2K scare, he began foraging again in 1999. But this time he decided he wanted to really live it. In just a few years, he took hundreds of classes from native people, botanists and survivalists, learning about native plants and how to find and eat them.

Today, Baudar lives in the Angeles National Forest in San Bernardino County. He teaches classes on subjects like eco-friendly foraging and plant identification. He admits he had no desire to get into fermentation when he began foraging. But eating wild plants meant he had to master food preservation techniques to eat the food year round, which he covers in his books (like Wildcrafted Fermentation). He learned there are three bacteria types that can be foraged locally – lactic acid, acetic acid and yeasts – their transformative microbial power harnessed through fermentation.

“My main job is to rediscover what people did in the old days,” Baudar says. “I’m not a crusader, I’m a teacher more than anything else.”

Biodiversity of Fermenting

Katz, meanwhile, was drawn to fermentation from gardening. Raised in New York’s Upper West Side, Katz eventually moved to a rural, off-the-grid community in Tennessee as a young adult. He planted a garden and learned to live a slower lifestyle.

“I was such a naïve city kid, I didn’t realize all the cabbage would be ready at the same time,” Katz says of his first garden. He learned to ferment sauerkraut first – garnering the nickname “Sandor Kraut” – and become a self-described “fermentation fetishist” from there.

“My interest in fermentation stems from my desire to get closer to where my food comes from. A lot of people have a craving to be more connected to their food,” says Katz. “Learning about common, wild plants and accessing them is a great way to do that. You get to know your environment better.”

Katz is known worldwide as a fermentation revivalist, bringing a renewed interest in the ancient food craft, especially in the U.S. He always preaches on fermentation’s safety.

“Fermentation is above all else a strategy for safety,” he says. “In the realm of raw fruits or vegetables, there are no cases of food poisoning from fermentation.”

Immersing vegetables into salt and water allows the lactic acid bacteria on the vegetables to thrive. If there were salmonella on a vegetable, for example, fermenting it creates an acidic environment where salmonella can’t survive.

“Acidification and alcohol are really strategies for safety because they make it impossible for the pathogens to grow,” he adds. “Everything we eat raw has incredible biodiversity on it that we don’t even recognize. The question of which of those organisms are going to become dominant for the fermentation, that’s what it’s all about, really. Manipulating the environmental conditions to encourage the ones we want and discourage the ones we don’t want.”

Hunting for Wild Plants

There’s an element to safety in foraging, too, “you really have to know what you’re doing,” Baudar cautions. “There are some plants that will definitely kill you. You have to go with certainty.”

Baudar will not forage in the city, though, especially along major roadways. The pollution in major metropolitan areas gets in the plants – he hunts in more pristine environments.

“You have to know where to forage,” he says. Still, people have healthy urban gardens. “Modern agriculture in my opinion is way worse than whatever you can forwage, with the amount of chemicals they put on there”

Baudar currently lives in an RV on property over 130 miles away from the city of Los Angeles. He moved from the city during the Covid-19 pandemic.

“One of the things I learned doing this is Los Angeles is really the capital of wild food,” he says. “Los Angeles is incredible in terms of wild, edible plants. What is fascinating is 90% of the wild, edible plants around Los Angeles are actually native and invasive.”

He points to the foothills and mountainsides surrounding Los Angeles and Southern California. In the spring, they’re a bright yellow color, covered with roughly 12 different types of wild mustard. Mustard could easily be preserved and put in the food stream – Baudar says other countries do this with wild mustard – but in California, the mustard is sprayed with Round Up and ripped out.

“The biggest food waste in Los Angeles is wild plants,” he adds. “But no one ever looks at wild food as food waste.”

Noma restaurant in Denmark is an excellent example of foraging. There was no Nordic cuisine based in native native plants until Noma revived it. “They practically rediscovered cuisine from scratch in the early 2000s,” he says.

Think of California cuisine and a modge podge of food from other cultures comes to mind – Mexican or Vietnamese food. California doesn’t have an identity with their native food. Baudar says every state could have their own sustainable cuisine based on edible, wild food.

“If you cook California cuisine in 2023, cuisine that is actually good for the environment by cooking those non-native and native plants, cuisine that’s sustainable because you’re replanting the plants, that’s native cuisine. And you do it without cultural appropriation because it’s native plants,” he says. “And it tastes really, really good. But foraging is not part of the big picture (for governments).”

- Published in Food & Flavor

Why did Americans Turn to Drinking ACV?

A deep dive on Epicurious explores how apple cider vinegar (ACV) became America’s favorite. It is popular today as a detox tonic, but has a deep history in the U.S., “intertwined with the global spread of apples and with the transformations of fermentation.”

Today, vinegar is considered an industrialized condiment but, until the 19th Century, it was homemade. Kirsten Shockey, author of Homebrewed Vinegar (and a TFA Advisory Board member) notes the key to making vinegar is nurturing the natural fermentation process. “Vinegar happens whether you want it to or not,” she says. “As soon as fruit is picked, it’s a race against time,” she adds. As the fruit ripens, wild yeasts ferment their sugars into alcohol. Microbes feast on that alcohol, converting it to acetic acid.

Paul C. Bragg, namesake of the Bragg vinegar brand, helped popularize commercial vinegar. Theirs is still a raw, unpasteurized ACV. Paul preached the benefits of vinegar as far back as in the 1970s. This support coincided with “the rise of a countercultural natural food movement, which embraced the brown, gritty and ‘all-natural’ in its refusal of the refined, bleached and heavily processed products of the industrial food system.” (Pop star Katy Perry invested in Bragg in 2019).

The article also highlights artisanal vinegar brands, like American Vinegar Works in Massachusetts and two Pennsylvania producers, Supreme and Keepwell.

Isaiah Billington cofounder of Keepwell says that making vinegar “helps us interact closely with the total landscape of local agriculture.” Vinegar also uses produce that can’t be sold because it’s too ripe, or because the apple is “very ugly.” “We work at the margins of the harvest.”

Read more (Epicurious)

- Published in Food & Flavor

Sandor Katz: “Don’t be Intimidated by Fermentation”

Further catapulting fermentation into the culinary zeitgeist: Sandor Katz was a guest on the Rachael Ray Show, talking about fermentation and sharing a homemade sauerkraut recipe.

“Everybody eats and drinks products of fermentation everyday,” Katz said on the show’s March 8 episode. “Fermentation, which is the transformation action of microorganisms, is so integral to how we make effective use of whatever food resources are available to us.”

Katz, author of six books on fermentation, stressed “bread is fermented, cheese is fermented, cured meats are fermented, condiments are either directly fermented or they rely on vinegar, which is a direct product of fermentation.”

Katz demonstrated how to make a sauerkraut for viewers, encouraging them: “Don’t be intimidated by fermentation.”

Read more (Rachael Ray Show)

- Published in Food & Flavor

Fermentation Tourism

The state of Pennsylvania has created a unique tourist experience, Pickled: A Fermented Trail. The self-guided, culinary tour showcases fermented food and drink from around the state.

The fermented trail is broken into five regional itineraries, and includes historic businesses, artisanal food makers and large producers. Stops range from an Amish gift shop that ferments root beer to a master chocolatier, from a kombucha taproom to a fermentation-focused restaurant, and from a fourth-generation cheesemaker to a convenience store that makes its own pickles, sauerkraut and vinegar. Mary Miller, cultural historian and professor, spent two years designing the trail.

“Cultured foods have been part of PA’s culinary culture since the beginning,” reads the Visit Pennsylvania Pickled: A Fermented Trail website. “Many groups that have migrated to Pennsylvania throughout history were fond of fermented foods for both health and flavor, as well as for preserving food through the winter.”

The website also features a history of fermented food and drink, both regionally and globally. It shares a brief overview of root beer, which was created in Pennsylvania as a sassafras-based, yeast-fermented root tea. And it notes that, while Germans brought sauerkraut to the state, the Chinese are believed to have been the first to ferment cabbage.

The fermented trail is one of Pennsylvania’s four new culinary road trips, along with those highlighting charcuterie, apples and grains. These paths aim to showcase the state’s culinary history, and preserve its foodways.

This unique culinary adventure — the first we have seen at TFA — could be a model for tourism in other states and countries.

Read more (Food & Wine)

- Published in Business

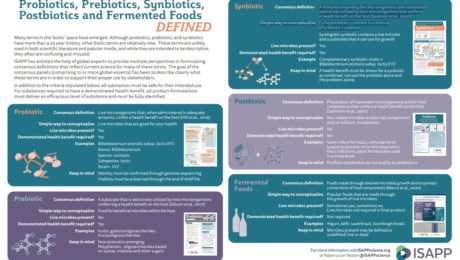

The Rise of Fermented Foods and -Biotics

Microbes on our bodies outnumber our human cells. Can we improve our health using microbes?

“(Humans) are minuscule compared to the genetic content of our microbiomes,” says Maria Marco, PhD, professor of food science at the University of California, Davis (and a TFA Advisory Board Member). “We now have a much better handle that microbes are good for us.”

Marco was a featured speaker at an Institute for the Advancement of Food and Nutrition Sciences (IAFNS) webinar, “What’s What?! Probiotics, Postbiotics, Prebiotics, Synbiotics and Fermented Foods.” Also speaking was Karen Scott, PhD, professor at University of Aberdeen, Scotland, and co-director of the university’s Centre for Bacteria in Health and Disease.

While probiotic-containing foods and supplements have been around for decades – or, in the case of fermented foods, tens of thousands of years – they have become more common recently . But “as the terms relevant to this space proliferate, so does confusion,” states IAFNS.

Using definitions created by the International Scientific Association for Postbiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP), Marco and Scott presented the attributes of fermented foods, probiotics, prebiotics, synbiotics and postbiotics.

The majority of microbes in the human body are in the digestive tract, Marco notes: “We have frankly very few ways we can direct them towards what we need for sustaining our health and well being.” Humans can’t control age or genetics and have little impact over environmental factors.

What we can control, though, are the kinds of foods, beverages and supplements we consume.

Fermented Foods

It’s estimated that one third of the human diet globally is made up of fermented foods. But this is a diverse category that shares one common element: “Fermented foods are made by microbes,” Marco adds. “You can’t have a fermented food without a microbe.”

This distinction separates true fermented foods from those that look fermented but don’t have microbes involved. Quick pickles or cucumbers soaked in a vinegar brine, for example, are not fermented. And there are fermented foods that originally contained live microbes, but where those microbes are killed during production — in sourdough bread, shelf-stable pickles and veggies, sausage, soy sauce, vinegar, wine, most beers, coffee and chocolate. Fermented foods that contain live, viable microbes include yogurt, kefir, most cheeses, natto, tempeh, kimchi, dry fermented sausages, most kombuchas and some beers.

“There’s confusion among scientists and the public about what is a fermented food,” Marco says.

Fermented foods provide health benefits by transforming food ingredients, synthesizing nutrients and providing live microbes.There is some evidence they aid digestive health (kefir, sourdough), improve mood and behavior (wine, beer, coffee), reduce inflammatory bowel syndrome (sauerkraut, sourdough), aid weight loss and fight obesity (yogurt, kimchi), and enhance immunity (kimchi, yogurt), bone health (yogurt, kefir, natto) and the cardiovascular system (yogurt, cheese, coffee, wine, beer, vinegar). But there are only a few studies on humans that have examined these topics. More studies of fermented foods are needed to document and prove these benefits.

Probiotics

Probiotics, on the other hand, have clinical evidence documenting their health benefits. “We know probiotics improve human health,” Marco says.

The concept of probiotics dates back to the early 20th century, but the word “probiotic” has now become a household term. Most scientific studies involving probiotics look at their benefit to the digestive tract, but new research is examining their impact on the respiratory system and in aiding vaginal health.

Probiotics are different from fermented foods because they are defined at the strain level and their genomic sequence is known, Marco adds. Probiotics should be alive at the time of consumption in order to provide a health benefit.

Postbiotics

Postbiotics are dead microorganisms. It is a relatively new term — also referred to as parabiotics, non-viable probiotics, heat-killed probiotics and tyndallized probiotics — and there’s emerging research around the health benefits of consuming these inanimate cells.

“I think we’ll be seeing a lot more attention to this concept as we begin to understand how probiotics work and gut microbiomes work and the specific compounds needed to modulate our health,” according to Marco.

Prebiotics

Prebiotics are, according to ISAPP, “A substrate selectively utilized by host microorganisms conferring a health benefit on the host.”

“It basically means a food source for microorganisms that live in or on a source,” Scott says. “But any candidate for a prebiotic must confer a health benefit.”

Prebiotics are not processed in the small intestine. They reach the large intestine undigested, where they serve as nutrients for beneficial microorganisms in our gut microbiome.

Synbiotics

Synbiotics are mixtures of probiotics and prebiotics and stimulate a host’s resident bacteria. They are composed of live microorganisms and substrates that demonstrate a health benefit when combined.

Scott notes that, in human trials with probiotics, none of the currently recognized probiotic species (like lactobacilli and bifidobacteria) appear in fecal samples existing probiotics.

“There must be something missing in what we’re doing in this field,” she says. “We need new probiotics. I’m not saying existing probiotics don’t work or we shouldn’t use them. But I think that now that we have the potential to develop new probiotics, they might be even better than what we have now.”

She sees great potential in this new class of -biotics.

Both Scott and Marco encouraged nutritionists to work with clients on first improving their diets before adding supplements. The -biotics stimulate what’s in the gut, so a diverse diet is the best starting point.

New FDA Requirements for Fermented Food

By August, any manufacturer labeling their fermented or hydrolyzed foods or ingredients “gluten-free” must prove that they contain no gluten, have never been through a process to remove gluten, all gluten cross-contact has been eliminated and there are measures in place to prevent gluten contamination in production.

The FDA list includes these foods: cheese, yogurt, vinegar, sauerkraut, pickles, green olives, beers, wine and hydrolyzed plant proteins. This category would also include food derived from fermented or hydrolyzed ingredients, such as chocolate made from fermented cocoa beans or a snack using olives.

Read more (JD Supra Legal News)

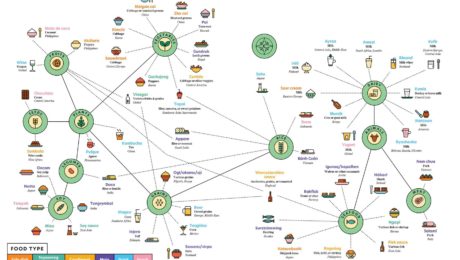

The World of Fermented Foods

In the latest issue of Popular Science, a creative infographic illustrates “the wonderful world of fermented foods on one delicious chart.” It represents “a sampling of the treats our species brines, brews, cures, and cultures around the world,” and is particularly interesting as it shows mainstream media catching on to fermentation’s renaissance. Fermentation fit with the issue’s theme of transformation in the wake of the pandemic.

Read more (Popular Science)

- Published in Food & Flavor

Apple Cider Vinegar Market Growing 12% through 2025

The global apple cider vinegar market expects over 12% CAGR through 2025, driven by use as a natural health remedy and digestive support. – Reportlinker

- Published in Business, Food & Flavor

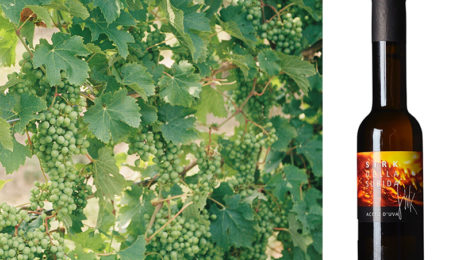

Fermented Grapes Make “Orange Wine” of Vinegars

The new innovation in vinegars is grape vinegars. Grape vinegar is made from grapes macerated and slowly allowed to ferment with their skins for a year. “The fermented juice then spends several years in small oak barrels to evolve into the delicately fruity pinkish vinegar,” according to the New York Times. The white grapes and skin contact is why the grape vinegar makers call it to the “orange wine” of vinegars. The latest grape vinegar collection comes from Sirk in Friuli, a region in northeast Italy. The grapes grown there, Ribolla Gialla white grapes, are prized for wine making.

Read more (New York Times)

- Published in Food & Flavor

Fermentation Reigns: Sour Taking Over Our Tastebuds

Sour is taking over our taste buds. A New York Times Style Magazine article explores how sour flavor is “dominating our dining discourse.” The article lists fermenting, kombucha, sourdough, kimchi, drinking vinegar, cocktail shrubs and sour beer as evidence of sour’s ascent in American’s palates. Samin Nosrat, author of the book of cohost of the Netflix series both titled “Salt, Fat, Acid, Heat,” says acid is one of the building blocks of flavor and makes our mouth water. “...your body gets confused — maybe I want more?”

Read more (New York Times Style Magazine)

- Published in Food & Flavor