Fermentation Tops Restaurant Trend List

“Pickling and fermenting preparations are having a moment,” reads the 2023 Foodservice Industry Trend Report from Technomic. The food trend forecaster’s annual list rates fermentation “The Power of Preserving” as one of their top seven industry trends.

“Not only do these preparations promote ingredient preservation and health connotations but they also allow for unique culinary experimentation,” the report reads.

Technomic anticipates fermented food crafts at the bar, like kombucha, miso and sake. But lacto-fermentation, they predict, will also make its way to the menu, as restaurants detail their preserving processes “to provide consumers with a level of scientific transparency.”

Read more (Technomic)

- Published in Food & Flavor

Infants Sleep More if Mom Eats Fermented Foods

Toddlers and infants slept 10 hours or more a night if their mother ate fermented foods while pregnant, according to a new Japanese study.

The results, published in the journal BMC Public Health, studied over 64,000 pairs of mothers and their children. The diet of pregnant mothers was found to have an impact on sleep length of their children. Pregnant women who consumed miso, yogurt, cheese and/or natto all had children that slept 10+ hours a night until the age of 3. The article calls it “fermentation for hibernation.”

The study notes, though, that there are other associated factors at play. The women consuming fermented foods were well-educated, employed and had higher incomes compared to the pregnant mothers not regularly consuming fermented foods. Scientists inferred that this higher demographic group “likely recognized factors that could contribute to health and chose nutrient-rich options [instead of] nutritionally-unbalanced food.”

Read more (NutraIngredients)

The Unsung History of Umami

In the early 1900s, Japanese chemist Dr. Kikunae Ikeda discovered the flavor umami by distilling it from soup stock. That compound – which is an amino acid, glutamate — produces the savory flavor in meat, mushrooms and seaweed. Ikeda called the flavor after the Japanese word umami which means “essence of deliciousness.”

“It is the peculiar taste which we feel as umai, meaning brothy, meaty or savory, arising from fish, meat and so forth,” Ikeda wrote in the Journal of Tokyo Chemical Society.

A huge discovery, umami became the fifth flavor next to salty, sweet, sour and bitter. Ikeda went on to start a company, Ajinomoto, which mass produces monosodium glutamate — MSG — a key ingredient in producing umami.

But it took nearly 100 years for umami to be recognized by the broader scientific community, especially in the western world. An NPR story points to the anti-Asian “Chinese Restaurant Syndrome” which began in the 60s and 70s. MSG was vilified as an unhealthy additive, numbing mouths and making people sick (an apparent fable modern food scientists have never been able to prove). Another reason: umami research may have been ignored in the U.S. because of tension with Japan during World War II .

“Fermented foods and seasonings like sake, soy sauce, miso were a large part of the diet in Japan and also a large part of the economy. And so research into the flavor components of those kinds of foods were an important part of rationalizing diet in Japan.”

says Victoria Lee, professor and author of “The Arts Of The Microbial World.”

Read more (NPR)

- Published in Food & Flavor

Scaling Artisanal Fermentation

Fungi fermenter Shared Cultures was the featured cover story in a recent Food & Wine section of the San Francisco Chronicle. Company co-owners Elena Hsu and Kevin Gondo make small-batch fermented soy sauce, miso, and sauces and marinades using koji and wild, foraged mushrooms.

The article calls Shared Cultures “the darling of the Bay Area food scene.” It details how they use traditional techniques with unexpected ingredients, like a shoyu with quinoa and lentils, a miso with cacao nib and a koji salt with leek flowers.

Hsu and Gondo also open up about the challenges of scaling artisanal fermentation. They are the only employees at the companys and can’t keep up with the demand. Their ferments require a lot of time, some fermenting for eight months in a closet-size room in their rented commercial kitchen. They note that it is too expensive to rent or purchase their own warehouse in the Bay Area.

Multiple California chefs use Shared Cultures products for an added umami punch. Hsu encourages home cooks to experiment with their products, too, “You don’t have to have a $300 tasting menu to try these flavors,” she says. “You can be the chef.”

Read more (San Francisco Chronicle)

- Published in Business, Food & Flavor

A Nutrition Pro’s Fermentation Guide

Nutrition professionals need to share the details when recommending fermented products to clients. What are the health benefits of the specific food or beverage ? Does the product contain probiotics? Live microbes?

“There are a vast array of fermented foods. This is important because it means there can be tasty, culturally appropriate options for everyone,” says Hannah Holscher, PhD and registered dietitian (RD). But, she adds, remember that these are complex products.

Holscher spoke at a webinar produced by the International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) and Today’s Dietitian. Joined by Jennifer Burton, RD and licensed dietitian/nutritionist (LDN), the two addressed the topic Fermented Foods and Health — Does Today’s Science Support Yesterday’s Tradition? Hosted by Mary Ellen Sanders, executive director of ISAPP, the presentation touched on the foundational elements of fermented foods, their differences from probiotics, the role of microbes in fermentation, current scientific evidence supporting health claims and how to help clients incorporate fermented foods in their diets.

Sanders called fermented foods “one of today’s hottest food categories.” Today’s Dietitian surveys show they are a top interest to dietitians, as the general public often turns to them with questions about fermented foods and digestive health.

Here are three factors highlighted in the webinar that dietitians should consider before recommending fermented foods and beverages.

Does It Contain Live Microbes?

Fermentation is a metabolic process – microorganisms convert food components into other substances.

In the past decade, scientists have applied genomic sequencing to the microbial communities in fermented foods. They’ve found there’s not just one microbe involved in fermentation, Holscher explained, there may be many. The most common microbes in fermented foods are streptococcus, lactobacillaceae, lactococcus and saccharomyces.

But deciphering which fermented food or beverages contains live microbes can be difficult.

Live microorganisms are present in foods like yogurt, miso, fermented vegetables and many kombuchas. But they are absent in foods that were fermented then heat-treated through baking and pasteurization (like bread, soy sauce, most vinegars and some kombucha). They’re also absent in fermented products that are filtered (most wine and beers) or roasted (coffee and cacao). And there are foods that are mistakenly considered fermented but are not, like chemically-leavened bread, vegetables pickled in vinegar and non-fermented cured meats and fish.

“The main take-home message is that it’s not always easy to tell if a food is a fermented food or not. So you may need to do more digging, either by reading the label more carefully or potentially contacting the food manufacturer,” Holscher said. “When we just think of if live microbes are present or not, a good rule of thumb is if that food is on the shelf at your grocery store, it’s very likely that it does not contain live microbes.”

Does It Contain Probiotics?

The dietitians stressed: probiotics are not the same as fermented foods.

“Probiotics are researched as to the strains and the dosages to be able to connect consumption of a probiotic to a health outcome,” Holscher said. “These strains are taxonomically defined, they’ve been sequenced, we know what these microorganisms can do. They also have to be provided in doses of adequate amounts of the live microbes so foods and supplements are sources of probiotics.”

Though fermented foods can be a source of probiotics, Holscher notes: “In most fermented foods, we don’t know the strain level designation.”

“For most of the microbes in fermented foods, we’ve just really been doing the genomic sequencing of those over the last 10 years and so we may only know them to the genus level right,” she said. For example, we know lactic acid bacteria are present in kimchi and sauerkraut.

Holscher suggests, if a client has a specific health need, a probiotic strain should be recommended based on its evidence-based benefits. For example, the probiotic strain saccharomyces boulardii is known to help prevent travel-related diarrhea, and so would be good for a patient to take before a trip.

“If you’re looking to support health and just in general, fermented foods are a great way to go,” Holscher says.

The speakers recommended looking for probiotic foods in the Functional Food Section of the U.S. Probiotic Guide.

Does Research Support Health Claims?

Fermentation contributes to the functional and nutritional characteristics of foods and beverages. Fermented foods can: inhibit pathogens and food spoilage microbes, improve digestibility, increase vitamins and bioactives in food, remove or reduce toxic substances or anti-nutrients in food and have health benefits.

But research into fermented foods has been minimal, mostly limited to fermented dairy. Dietitians should be careful making strong recommendations based on health claims unless those claims are supported by research. And food labels should always be scrutinized.

“There’s a lot of voices out there that are trying to answer this question [Are fermented foods good for us?],” says Burton. “Many food manufacturers have published health claims on their labels talking about these benefits and, while those claims are regulated, they’re not always enforced. Just because it has a food health claim on it, that claim may not be evidence-based. There’s a lot of anecdotal accounts of benefits coming from eating fermented foods and the research is suggesting some exciting potential mechanisms. But overall we know as dietitians we have an ethical responsibility to practice on the basis of sound evidence and to not make strong recommendations if those are not yet supported by research.”

Reputable health claims are documented in randomized control trials. But only “possible benefits” can be linked to nonrandomized controlled trials. And non-controlled trials are the least conclusive studies of all.

For example, Burton puts miso in the “possible benefits” category because, with its high sodium content, there’s not enough research indicating it’s safe for patients with heart disease. Similarly, she does not recommend kombucha because of its extremely limited clinical research and evidence.

“We have to use caution in making these recommendations,” Burton says.

This is why Burton advises dietitians to be as specific as possible. Don’t just tell patients “eat fermented foods” — list the type of fermented food and its brand name. She also says to give patients the “why” — what is the benefit of this fermented food? Does it increase fiber or boost bioavailability of nutrients?

“Are fermented foods good for us? It’s safe to say yes,” Burton says. “There’s a lot that we don’t know, but the body of evidence suggests that fermentation can improve the beneficial properties of a food.”

Retail Sales Trends for Fermented Products

Miso, frozen yogurt and pickled and fermented vegetables are driving growth in the $10.97 billion fermented food and beverage category. The fermented products space grew 3.3% in 2021, outpacing the 2.1% growth achieved by natural products overall.

“It really highlights how functional products have become the norm for shoppers when they’re in stores,” says Brittany Moore, Data Product Manager for Product Intelligence at SPINS LLC, a data provider for natural, organic and specialty products. Moore notes there’s an “explosion of functional products” in the market — “[they] are appearing everywhere. And fermented products have been leading that space in the natural market for years.”

The data was shared during TFA’s conference, FERMENTATION 2021. SPINS worked with TFA to drill into data covering 10 fermented product categories and 64 product types (an increase from last year). [A note that wine, beer and cheese sales are excluded from the data. These categories are very large, and would obscure trends in smaller segments. Wine, beer and cheese are also well-represented by other organizations.]

Yogurt dominates the fermented food and beverage landscape with 75% of the market, but sales growth is soft. Frozen yogurt and plant-based offerings, though small portions of the yogurt category, are fueling what growth there is. “Novelty products are catching shopper’s eyes,” Moore notes.

Kombucha, the fermented tea which led the U.S. retail revival of fermented products, still rules the non-alcoholic fermented beverages market, with 86% of sales. But growth is slowing. Moore points out that this slowdown is due to kombucha having penetrated the mass market with lots of brands on grocery shelves.

“There’s opportunity in kombucha for new innovations to catch the progressive shopper’s eye,” Moore says. “Shoppers are looking for an innovative twist to their functional product.”

Moore points to successful twists like hard kombucha, which grew nearly 60%, and probiotic sodas, which grew 31%.

Growth is slowing for hard cider, too, though hard cider leads the alcoholic beverages category with 83% share of sales.

All sectors of the pickled and fermented vegetables category are growing, totalling nearly $563 million in sales. Refrigerated products are nine of the top 10 subcategories here. The “other” pickled vegetable subcategory is increasing at a 60% growth rate, “other” being the catch-all for vegetables that are not cucumbers, cabbage, carrots, tomatoes, beets or ginger. Fermented radish, garlic and seaweed fall into this subcategory.

Soy sauce is not surprisingly still the largest product in sauces, representing 58% of the category. But that share is dropping. Gochujang is the growth leader, increasing at rate of nearly 20%.

Miso and tempeh are also performing well, which Moore attributes to the growing plant-based movement and the Covid-19 pandemic pantry stocking boom. Miso products — soups, broths, pastes and mixes — totaled over $24 million in sales in 2021. Though instant soups and meal cups represented only 8% of sales, they grew more than 110%.

- Published in Business

Preserving Japan’s Miso Culture

A Japanese public-relations-exec-turned-chef has developed a unique product — Miso Drops, individually-sized servings of stock. She felt it was difficult for an individual customer to use miso from traditional breweries because they only ship products weighing at least 500 grams. Her drops weigh around 26 grams.

Entrepreneur Motomi Takahashi, “alarmed by the gradual disappearance of small-scale miso breweries that have been a key part of Japan’s tradition of fermented foods,” created the soybean paste balls using traditional methods. And, different from the large factories that mass-produce miso products, Takahashi’s miso drops are handmade.

Important to Takahashi is preserving Japan’s rich miso culture. Small-scale miso brewing in the country is “in danger of extinction,” notes an article in Kyodo News. In Japan’s Nagano Prefecture, where most of the miso in the country is made, the number of miso breweries declined 42% from 1963-2010.

Takahashi is developing a product line called misodrop47, which will feature miso drops made in each of Japan’s 47 prefectures. Currently, hermiso drops come from eight.” I wanted to develop products for the misodrop47 project to allow customers to casually sample miso from all over Japan,” she says.

Read more (Kyodo News)

- Published in Business, Food & Flavor

Japan’s Rich Culture of hakkо̄

“If there were a country whose cuisine excels in the realm of fermented foods, it’s Japan,” highlights an article in Discover Magazine. In Japan, hakkо̄ (which translates to “fermentation”) forms “the very basis of gastronomy in the island nation,” continues the article.

Tsukemono (pickles), miso (fermented soy bean paste), soy sauce, nattо̄ (fermented soy beans), katsuobushi (dried fermented bonito flakes), nukazuke (vegetables pickled in rice bran), sake and shōchū (liquor distilled from rice, brown sugar, buckwheat or barley) are all staples of traditional Japanese meals.

Nattо̄ in particular has been proven to lower obesity rates, boost levels of dietary fiber, protein, calcium, iron and potassium and reduce diastolic blood pressure.

Though the article highlights the few, limited studies on the effects of other fermented foods, it also noted how difficult it is to study them. There little money behind the study of traditional foods (outside of yogurt), and participants in any such research would need to be on the same diets and exercise programs in order to produce objective results. A study would also need to take place over multiple years — “the cost would be vast, the ethics questionable.”

Read more (Discover Magazine)

- Published in Food & Flavor

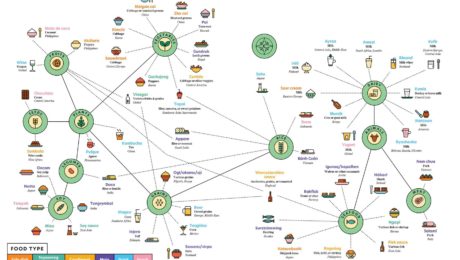

The World of Fermented Foods

In the latest issue of Popular Science, a creative infographic illustrates “the wonderful world of fermented foods on one delicious chart.” It represents “a sampling of the treats our species brines, brews, cures, and cultures around the world,” and is particularly interesting as it shows mainstream media catching on to fermentation’s renaissance. Fermentation fit with the issue’s theme of transformation in the wake of the pandemic.

Read more (Popular Science)

- Published in Food & Flavor

Reinventing 144-year-old Miso Company

Yoko Nagatomo Shiomi, president of the fourth-generation Kanena Miso & Soy Sauce Brewery, is one of few female toji (head brewers) in the miso industry. Japanese traditions delegate that businesses are passed onto male heirs. But when Shiomi’s father suffered a debilitating stroke, she was the only heir left.

Shiomi’s great-grandparents started the miso and soy sauce brewery in 1877. Shiomi never expected to inherit the company. “I had no expertise or information, and knew it was uncommon for girls to do this type of work, however I needed to strive,” she says. Before officially taking over, Shiomi and her mother spent three years with the company’s brewers learning the intricacies of the business. Like the most effective ways to combine soybeans and barley with koji spores.

Though miso and soy sauce have long been staples in Japanese dining, Shiomi told the Japan Times she was shocked to learn how much miso consumption had declined in the average household. “Miso is a really nutrition fermented seasoning and really authentic to our tradition,” she said. She began volunteering to teach kids how to cook with miso. It also inspired her to create a new miso product easier to use for the modern shopper: dried miso packets, make-your-own miso kits, and miso-marinated cuts of pork.

Read more (Japan Times)

- Published in Business, Food & Flavor

- 1

- 2