Can Wine Industry Court Younger Audience?

“The American Wine Industry Has an Old People Problem,” reads the headline from the New York Times. The article dives into the challenge highlighted by a new report: winemakers are missing younger consumers. The biggest growth area is among 70- to 80-year-olds.

“It’s worse than I thought,” Mr. McMillan said in a phone interview. “I thought we would have made some progress with under-60s. I’ve been talking about this problem for seven years and we still haven’t reacted.”

Younger consumers have a plethora of trending alcoholic drinks to choose from, much more than baby boomers. Craft beers, hard kombucha, hard seltzers and canabis-infused cocktails all compete with wine.

Rob McMillan, executive vice president of Silicon Valley Bank and author of the State of the U.S. Wine Industry 2023 report, says he believes wine’s downfall is a marketing problem. His tips:

- Emphasize social responsibility with the environmental sustainability of wine

- Embrace health awareness with ingredient labeling and transparent nutrition

- More introductory wines, like wine coolers, wines mixed with carbonated water and sold in cans, wines sold in smaller bottles

- More advertising and promotion targeted to a younger audience

Read more (New York Times)

- Published in Business

Endangered Fermented Foods

Through selective breeding and domestication of plants and livestock, the world’s food system has lost diversity to an alarming degree. Crops are monocultures and animals are single species. Journalist and author Dan Saladino argues it’s vital to the health of humanity and our planet to save these traditional foods.

“There’s an incredible amount of homogenization taking place in the last century, which has resulted in a huge amount of concentration of power in the food system but also a decline in the amount of biodiversity,” says Saladino, author of Eating to Extinction. “That agricultural and biological diversity is disappearing and it’s taken us thousands, millions of years for plant, animal evolution to get to this point.”

Saladino was a keynote speaker at The Fermentation Association’s conference FERMENTATION 2022, his first in-person talk in the United States since his book was released in February. A journalist with the BBC, Saladino was also an active participant in the event, attending multiple days’ worth of educational sessions. He called the conference “mind expanding.”

“I thought I knew about fermentation, when in fact I know very little,” Saladino said to the crowd in his keynote. “We’ve been bemused by the media reports that fermentation is a fad or fashion. What we know is that the modern food system in the last 150 years is the fad. It’s barely a blip in the context of our evolution as species, and it’s the way we’ve survived as a species over thousands of years.”

Eating to Extinction includes 40 stories of endangered foods and beverages, just touching on a fraction of what is happening around the world. To date, over 5,000 endangered items from 130 different countries have been cataloged by the Slow Food Foundation’s project the Ark of Taste.

During FERMENTATION 2022, Saladino centered his remarks around the endangered fermented foods he chronicled in his book – Salers cheese, skerpikjøt, oca, O-Higu soybeans, lambic beer, pu’erh tea, qvevri wine, perry and wild forest coffee. Here are some of the highlights of his presentation.

Salers cheese (Augergne, Central France)

Fermentation was a survival strategy for many early humans, a fact especially evident in the origins of cheesemaking. In areas like Salers in central France, villagers live in inhospitable mountain areas where it’s difficult to access food. In the spring each year, cheesemakers travel up the mountains with their cattle and live like nomads for months.

“It’s extremely laborious, hard work,” Saladino says, noting there’s only a handful of Salers cheese producers left in France. He marvels at “the ingenuity of taking animals up and out to pasture in places where the energy from the sun and from the soil is creating pastures with grasses with wildflowers and herbs and so on.”

Unlike with modern cheese, no starter cultures are used to make Salers cheese. The microbial activity is provided by the environment – the pasture, the animals and even the leftover lactic acid bacteria in the milk barrels. Because of diversity, the taste is rarely consistent, ranging season to season from mild to aggressive.

“The idea of cheesemaking is a way humans expand and explore these new territories assisted by the crucial characters in this: the microbes,” he adds. “It can be argued that cheese is one of most beautiful ways to capture the landscape of food – the microbial activity in grasses, the interaction of breeds of animals that are adapted to the landscape. It’s creating something unique to that place.”

Skerpikjøt (Faroe Islands)

Skerpikjøt “is a powerful illustration to our relationship with animals, with meat eating,” Saladino says. It is fermented mutton and unique to Denmark’s Faroe Islands. Today’s farmers selectively breed their sheep for ideal wool production, then slaughter the lambs for meat. In the Faroes, “the idea of eating lamb was a relatively new concept.” Sheep are considered vital to the farm as long as they’re still producing wool and milk.

Once a sheep dies or is killed, the mutton carcass is air-dried and fermented in a shed for 9-18 months. The resulting product is “said to be anything between Parmesan and death. It certainly has got a challenging, funky fragrance,” Saldino says.

But it contrasts traditional and modern food practices. Skerpikjøt is meant to be consumed in small quantities, delicate slivers of animal proteins used as a garnish. Contemporary meat is served in large portions and meant to be consumed quickly.

Oca (Andes, Bolivia),

In the Andes – “one of the highest, coldest and toughest places on Earth to live” – humans have relied on wild plants like oca, a tuber. After oca is harvested, it’s taken to the Pelechuco River. Holes are dug on the riverbank, then filled with water, hay and muna (Andean mint). Sacks of oca are placed in the holes, weighted down by stones, and left to ferment for a month. This process is vital as it leaches out acid.

“Through processing, this becomes an amazing food,” Saladino says.

But cities are demanding certain types of potatoes, encouraging remote villagers to plant monocultures of potatoes which are prone to diseases. The farmers end up in debt, buying fertilizers and pesticides to grow potatoes.

“For thousands of years, oca and this fermentation technique and the process to make these hockey pucks of carbohydrates and energy kept them alive in that area,” Saladino says. “It’s a diversity that is fast disappearing from the Andes.”

O-Higu soybeans (Okinawa, Japan)

The modern food industry is threatening the O-Higu soybean, too. It was an ideal soybean species – fast-growing, so it can be harvested before the rainy season and the arrival of insects.

“But by the 20th century, the soy culture pretty much disappeared,” Saladino says.

With World War II came one of America’s biggest military bases to Japan. U.S. leaders dictated what food could be planted on the island. Okinawa was self-sufficient in local soy until American soy was introduced.

Lambic Beer (Belgium)

Saldino explained that, after a spring/summer harvest, Belgian farmers became brewers. They used their leftover wheat to create brews unique to the region.

But by the 1950s and 1960s, larger brewers began buying up the smaller ones. Anheuser-Busch InBev now produces one in four beers drunk around the world.

“There [is] story after story of these distinctive, unique, small breweries disappearing as they are bought up or absorbed into this growing, expanding empire of brewing,” Saladino says. “It’s probably one of the most striking cases of corporate consolidation of a drink and food product.”

Saladino stressed not all is lost. He shared stories of scientists, researchers and local people trying to save endangered foods, collecting seeds, restoring crops and combining traditional and modern-day practices to preserve the world’s rare foods.

“There have been so many fascinating stories of science and research discussed over the last few days at this conference, and I think the existence of The Fermentation Association is exciting because it is bringing together tradition, culture, science, culinary skills, all of these things we know food is,” Saladino added. “Food is economics, politics, geography, anthropology, nutrition. What I’m arguing is that these clues or glimpses into the past for these endangered foods, they’re not just some kind of a food museum or an online catalog. They are the solutions that can help us resolve some of the biggest food challenges we have.”

- Published in Food & Flavor

Non-Alcoholic Wine: “This is definitely not a fad”

The first non-alcoholic wine shop has opened in Paris. An NPR article questions: Will the French actually drink their products?

Alcohol-free wine and liquor shop Le Paon Qui Boit (translation: The Drinking Peacock) opened in April, the brainchild of lawyer Augustin Laborde. The shop sells more than 300 bottles of low- and zero-proof beers, wines, gins and whiskeys. Laborde quit drinking during the pandemic and was frustrated going to bars with friends and finding his only non-alcoholic options were sugar-filled sodas or fruit juices.

The bottles have high price tags in Paris, at 10 to 15 euros (compared with 4 to 8 euros for an alcoholic version). Laborde says there are extra steps involved in making a non-alcoholic wine. After going through traditional fermentation, the alcohol in wine is evaporated through a filtration process.

Non-alcoholic wine consumption globally has grown 24% in the last year, according to consulting group IWSR Drink Market Analysis. Dan Mettyear, research director at IWSR, says “This is definitely not a fad…it’s all connected to the kind of big wellness trends that we’ve seen across the world.”

Growth, though, has been slower in France than in the U.S. and the rest of Europe. He says it’s a harder sell in traditional wine markets like France. “A lot of people have already well-established ideas about what wine is and what wine should taste like.”

But there are wineries transitioning to the production of non-alcoholic wines, such as Le Petit Béret, a small producer in southern France. And Laborde says he anticipates the flavor of non-alcohol wine to become more refined, as techniques improve and the market grows.

Read more (NPR)

- Published in Food & Flavor

Naked Wine

Olfactory properties are central to the wine drinking experience. But a chemical reaction known as light strike can ruin the rich aroma. When wine is exposed to ultraviolet or high frequency visible light, its smell can resemble marmalade. Sauerkraut or even wet dog.

This is why wine is stored and aged in dark bottles – the color glass is crucial to producing a great wine.

“Every technician knows about it,” says Fulvio Mattivi, a food chemist at the Edmund Mach Foundation in Italy. “But then the final decision as to what goes on the market is up to the head of marketing.”

Mattivi and collaborators recently published a paper in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences detailing how bottle color affects light strike in wine on grocery store shelves.

Clear bottles made of a refractive material called flint glass are often used to sell white wine and rosé, to show off the fermented beverage’s color. The new research shows that just a week on supermarket shelves in clear bottles can produce smelly compounds. “With exposure, you can have a very bad wine,” Mattivi said. This chemical origin of light strike, including the speed and conditions, has been unknown until Mattivi’s study. In his team’s research, more than 1,000 wine bottles in different grocery store conditions were studied.

Despite consumer preferences for clear bottles, Mattivi gives a hard “no.” He compares it to the folk tale, “The Emperor’s New Clothes.” In the Hans Christian Andersen story, the emperor is conned by swindlers into believing the new clothes they bring him are beautiful – but, in reality, there are no clothes and the emperor is naked.

Mattivi said: “Wine in clear bottles is naked.”

Read more (New York Times)

AI-Generated Wine Reviews?

New artificial intelligence software writes wine and beer reviews said to be indistinguishable from those by human critics. Researchers hope this tool will help wine and beer producers aggregate more reviews, and also provide human reviewers with a template. But the software has a major limitation: it cannot accurately predict the flavor profile of a beverage, something that can only be sampled and described by human taste buds.

Keith Carlson of Dartmouth College, who co-developed the algorithm, said wine and beer are perfect for AI-generated text because of the variety of their descriptors. Fermentation style, growing region, grape or wheat variety and year of production are all mentioned in reviews, aiding the AI algorithm. Reviews also tend to use the same vocabulary — words like “oaky,” “floral” and “dry.”

“People talk about wine in the same way, using the same set of words,” Carlson said, adding “it was just a very unique data set.”

The research team — interdisciplinary scientists from Dartmouth, Indiana University and The Santa Fe Institute — used more than a decade’s worth of reviews (over 125,000) from Wine Enthusiast, and 143,000 beer reviews from the website RateBeer. Results were published in the International Journal of Research in Marketing.

Next, they envision using the software for other experiential products, such as coffee or cars.

Read more (Scientific American)

- Published in Business

An Overlooked Wine Category

“Aaliyah Nitoto, winemaker at Free Range Flower Winery, is tired of hearing that the category of wine is exclusive to grapes. For centuries, wine has been made from many kinds of plant products, she says, like grapes, apples, pears, rice and flowers,” reads an article in Wine Enthusiast.

The magazine highlights the history of flower wine, which has variations in the Middle East, Asia, Europe and even the U.S. The process to make the wine is different from a traditional grape wine. Fresh or dried flowers are boiled and crushed, then yeast and a sugar source are added to start the fermentation process.

Flower winemakers lament that their product is not respected in the wine industry. Flower wine has been made primarily by middle- to lower-income women.

“That can tell you right there why they were relegated to obscurity. The people who owned tracts of lands that had money and influence and got to name things like ‘noble grapes,’ they got to say what was wine and what wasn’t,” Nitoto (pictured) adds. “The opinion of people in this country over the last 100-odd years to try to get rid of this category doesn’t stand up to the history of winemaking, which is thousands of years old, which does call this wine.”

Read more (Wine Enthusiast)

- Published in Food & Flavor

Upcycling Olive Oil, Wine & Beer Byproducts

The olive oil, wine and beer industries each create an enormous amount of waste. Producers, vintners, and brewers dispose of millions of tons of pomace and spent grains every year, often at a big cost.

To a crowd of food industry professionals at Natural Products Expo West, professors at University of California, Davis, shared their research into how these byproducts can be upcycled.

“There’s a lot of waste that can be generated doing agriculture and food processing,” said Selina Wang, PhD, Cooperative Extension Specialist in the Food, Science and Technology department. Globally, good waste is estimated at 140 billion tons a year. “That is a lot, but also a lot of opportunities for us to explore.”

Olive Oil Waste

Wang, who researches small-scale fruit and vegetable processing, says olive oil needs a byproduct solution. Oil is only 20% of an olive’s weight – the other 80% is discarded in olive oil production. Globally, the industry generates 20-30 million tons of olive pomace a year.

What industry, Wang questions, would operate using only 20% of their commodity?

“This is an industry that has been made to use the minor product. But we know there’s a lot of values in the byproduct,” Wang says. Olive pomace has numerous active health compounds which, when consumed, are proven to prevent disease like cancer, Type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease. But disposing of this byproduct creates a large carbon footprint. “Can we have a solution to climate change while at the same time improving our health?”

Many producers use the waste as animal feed, giving it away to ranchers. But often, the cost of transportation is too high to justify the benefits. And using olive pomace for compost is not ideal, as it has a negative effect on soil microbes.

In a recent UC Davis study, olive pomace was added to pasta, bread and granola bars, which were then tested for consumer acceptance. Tastes were strong and the grains turned purple when the pomace was added, so the amount of pomace added was low (7% in the pasta and 5% in the bread and granola bars). Consumers didn’t hate the products – they liked them slightly less than the unfortified versions – but the majority said they wouldn’t pay more for the items made with olive pomace.

“I would challenge us to think outside the status quo,” Wang says. “Olive oil was an industry developed with tradition, love and passion. But does it make sense to have an industry where we’re using only 20% of raw material? Or do we actually have an industry focusing on the 80% and the 20% is a wonderful gift we give to family and friends?”

Grape Waste

Further UC Davis studies are also looking at wine byproducts The global wine industry produces 10-13 million tons of grape pomace annually.

That waste is rich in flavonoids and oligosaccharides. UC Davis and Iowa State are currently studying the flavonoids as natural antioxidants and the oligosaccharides as prebiotics, and if they would have a synergetic effect on gut health.

“It basically shows there’s a second life to winemaking and the wine byproduct that’s generated,” she said.

Researchers at UC Davis who have studied feeding cows seaweed to reduce greenhouse gas emissions have proposed to the California Research Dairy Foundation that they use grape pomace instead. It’s cheaper than seaweed and cows burp less after consuming grapes.

Other industries, such as cosmetics, pet food and construction, could also use the byproducts. For example, a new study shows how construction companies could use olive pomace in asphalt paving and building materials.

Brewing Waste

Waste streams are an even bigger problem for the brewing industry, says Glen Fox, PhD, the Anheuser-Busch endowed professor of Malting and Brewing Science at UC Davis. Brewers globally produce over 49 million tons of spent grain a year.

That waste is high in water content (about 80%), but most brewers don’t have the ability to store wet grain. Similar to olive and grape pomace, it’s cheap feed for animals. But the cost of transporting spent grain outweighs the benefits for most breweries.

“At the moment, they’re giving it away,” he says. “They would like to get something back for it.”

Fox sees big opportunities for food producers to use brewing grains, which are packed with nutrients. Compounds can be extracted, such as dietary fiber for supplements, hydrocinnamic acid for makeup and even cellulose pulp for toilet paper. Fox is working on a patent for a process that would allow grains to be applied directly to soil.

The craft brewing industry is “the most viral business in America,” Fox said. There are breweries everywhere – some 9,000 craft brewers in the U.S., with over 1,000 in California alone. But there are not nearly as many food production facilities that can collect the spent grains.

“This industry is in an advantageous position because it has that waste stream every day,” Fox says. “If you want to potentially use this in your business, you don’t have to look far for your supplier.”

When Will the Food Industry Innovate?

“We have to start rethinking our food systems – farm to mouth,” Fox said. “It’s a big challenge.”

There’s no shortage of high-quality research on options for olive oil, wine and beer byproducts, Wang points out. The food industry needs to innovate profitable, desirable products made from upcycled ingredients. At one point whey – a byproduct of cheese production – was dumped down the drain, Wang said. Now it’s a popular protein supplement, in powders and bars.

Two brands are making inroads. Vine to Bar uses grape pomace to make chocolate. ReGrained uses spent beer grains to make pastas, bars and puffs.

“The key is we need to go from a linear economy – which is just made to waste – to a circular economy where we can avoid generating these wastes by upcycling every waste or every byproduct that we generate,” Wang said.

World’s Rarest Foods in Danger of Extinction

Journalist Dan Saladino explores the world’s endangered foods in his new book Eating to Extinction: The World’s Rarest Foods and Why We Need to Save Them. He argues that the world could lose culinary diversity. “The story of these foods, and the way in which they’re presented in the book,” says Saladino, from wild foods associated with hunters and gathers, to cereals, vegetables, meats and more, “is really the story of us and our own evolution.”

A review of Saladino’s book in Smithsonian Magazine shares 10 of the world’s rarest foods — five of them fermented. These rarities include:

- Skerpikjøt (Faroe Islands, Denmark): Dried and fermented mutton made from the shanks and legs of sheep. It ferments in wooden sheds called hjallur, which have vertical slats that allow space for the salty sea wind to blow in.

- Salers cheese (Auvergne, France): One of the world’s oldest raw milk cheeses made from the milk of Salers cows. The semi-hard cheese is made with varying fermentation lengths, which change the flavor.

- Qvevri wine (Georgia): Winemakers fill the egg-shaped terracotta pots called qvevri with grape juice, skins and stalks, then bury the pots underground. The steady temperatures and the pot’s shape allows even fermentation.

- Ancient Forest Pu-Erh Tea (Xishuangbanna, China): The fermented tea is made from wild tea leaves that grow in China’s southwestern Yunnan province. The leaves are sun-dried, cooked, kneaded, then formed into solid cakes and fermented for months (or years).

- Criollo Cacao (Cumanacoa, Venezuela): The world’s rarest type of cacao, it represents less than 5% of the cocoa production on the planet. The bean lacks bitterness, but is difficult to grow.

Read more (Smithsonian Magazine)

- Published in Food & Flavor

The Rise of Fermented Foods and -Biotics

Microbes on our bodies outnumber our human cells. Can we improve our health using microbes?

“(Humans) are minuscule compared to the genetic content of our microbiomes,” says Maria Marco, PhD, professor of food science at the University of California, Davis (and a TFA Advisory Board Member). “We now have a much better handle that microbes are good for us.”

Marco was a featured speaker at an Institute for the Advancement of Food and Nutrition Sciences (IAFNS) webinar, “What’s What?! Probiotics, Postbiotics, Prebiotics, Synbiotics and Fermented Foods.” Also speaking was Karen Scott, PhD, professor at University of Aberdeen, Scotland, and co-director of the university’s Centre for Bacteria in Health and Disease.

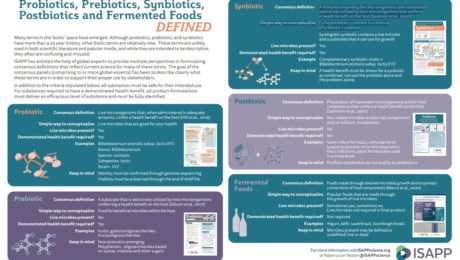

While probiotic-containing foods and supplements have been around for decades – or, in the case of fermented foods, tens of thousands of years – they have become more common recently . But “as the terms relevant to this space proliferate, so does confusion,” states IAFNS.

Using definitions created by the International Scientific Association for Postbiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP), Marco and Scott presented the attributes of fermented foods, probiotics, prebiotics, synbiotics and postbiotics.

The majority of microbes in the human body are in the digestive tract, Marco notes: “We have frankly very few ways we can direct them towards what we need for sustaining our health and well being.” Humans can’t control age or genetics and have little impact over environmental factors.

What we can control, though, are the kinds of foods, beverages and supplements we consume.

Fermented Foods

It’s estimated that one third of the human diet globally is made up of fermented foods. But this is a diverse category that shares one common element: “Fermented foods are made by microbes,” Marco adds. “You can’t have a fermented food without a microbe.”

This distinction separates true fermented foods from those that look fermented but don’t have microbes involved. Quick pickles or cucumbers soaked in a vinegar brine, for example, are not fermented. And there are fermented foods that originally contained live microbes, but where those microbes are killed during production — in sourdough bread, shelf-stable pickles and veggies, sausage, soy sauce, vinegar, wine, most beers, coffee and chocolate. Fermented foods that contain live, viable microbes include yogurt, kefir, most cheeses, natto, tempeh, kimchi, dry fermented sausages, most kombuchas and some beers.

“There’s confusion among scientists and the public about what is a fermented food,” Marco says.

Fermented foods provide health benefits by transforming food ingredients, synthesizing nutrients and providing live microbes.There is some evidence they aid digestive health (kefir, sourdough), improve mood and behavior (wine, beer, coffee), reduce inflammatory bowel syndrome (sauerkraut, sourdough), aid weight loss and fight obesity (yogurt, kimchi), and enhance immunity (kimchi, yogurt), bone health (yogurt, kefir, natto) and the cardiovascular system (yogurt, cheese, coffee, wine, beer, vinegar). But there are only a few studies on humans that have examined these topics. More studies of fermented foods are needed to document and prove these benefits.

Probiotics

Probiotics, on the other hand, have clinical evidence documenting their health benefits. “We know probiotics improve human health,” Marco says.

The concept of probiotics dates back to the early 20th century, but the word “probiotic” has now become a household term. Most scientific studies involving probiotics look at their benefit to the digestive tract, but new research is examining their impact on the respiratory system and in aiding vaginal health.

Probiotics are different from fermented foods because they are defined at the strain level and their genomic sequence is known, Marco adds. Probiotics should be alive at the time of consumption in order to provide a health benefit.

Postbiotics

Postbiotics are dead microorganisms. It is a relatively new term — also referred to as parabiotics, non-viable probiotics, heat-killed probiotics and tyndallized probiotics — and there’s emerging research around the health benefits of consuming these inanimate cells.

“I think we’ll be seeing a lot more attention to this concept as we begin to understand how probiotics work and gut microbiomes work and the specific compounds needed to modulate our health,” according to Marco.

Prebiotics

Prebiotics are, according to ISAPP, “A substrate selectively utilized by host microorganisms conferring a health benefit on the host.”

“It basically means a food source for microorganisms that live in or on a source,” Scott says. “But any candidate for a prebiotic must confer a health benefit.”

Prebiotics are not processed in the small intestine. They reach the large intestine undigested, where they serve as nutrients for beneficial microorganisms in our gut microbiome.

Synbiotics

Synbiotics are mixtures of probiotics and prebiotics and stimulate a host’s resident bacteria. They are composed of live microorganisms and substrates that demonstrate a health benefit when combined.

Scott notes that, in human trials with probiotics, none of the currently recognized probiotic species (like lactobacilli and bifidobacteria) appear in fecal samples existing probiotics.

“There must be something missing in what we’re doing in this field,” she says. “We need new probiotics. I’m not saying existing probiotics don’t work or we shouldn’t use them. But I think that now that we have the potential to develop new probiotics, they might be even better than what we have now.”

She sees great potential in this new class of -biotics.

Both Scott and Marco encouraged nutritionists to work with clients on first improving their diets before adding supplements. The -biotics stimulate what’s in the gut, so a diverse diet is the best starting point.

Alcohol Levels in Wine Continue to Rise

The alcohol levels in wine have been rising over the past 30 years — and wine experts say the sugar content in grapes is to blame.

Though a winemaker can manipulate sugar levels in the vineyard and alcohol levels in the cellar, a hotter climate is driving increased sugar content in grapes. California’s wine grapes have had a “substantial rise” in sugar levels since 1980. A study by the American Association of Wine Economists (AAWE) hypothesizes global warming is contributing.

Read more (Decanter)

- Published in Food & Flavor