Natural Production Changing the Wine Industry

Natural winemaking is moving mainstream, as more viticulturists preach the importance of soil health and shun traditional herbicides. “Where does natural wine finish and conventional wine start? These days, it’s hard to tell,” reads an article in Vinepair. Though the vast majority of global wine production still relies on conventional methods, the virtues of natural winemaking are helping change the industry.

“While it used to be rare for wines to be fermented with wild yeast — allowing the microbes present on the grapes to carry out fermentation — this is now much more common. And conventional producers have been prompted to question their use of additives such as sulfur dioxide. In fact, many aspects of winemaking that were championed by natural wine folk have now become much more common, even replacing some of the triumphs of more heavy-handed methods. As more producers trend away from making big, international-style reds with dark color, sweet fruit, high alcohol, and obvious new oak character, extracting less color and tannin for lighter-style reds is gaining popularity.”

Read more (Vinepair)

- Published in Food & Flavor

Sake Brewers Suffer in Japan

As Covid-19 restrictions are lifted, American sake breweries are opening their doors to customers again. But across the world in Japan, where sake originated, many izakaya or sake pubs remain closed. Japanese brewers expect sales to slump for a second year in a row because of the pandemic.

“This right now might be the most challenging time for the industry,” says Yuichiro Tanaka, president of Rihaku Sake Brewing. “There’s nothing much we can do about that. In our company, we’re trying to become more efficient and streamline our processes so that once the world economy returns to what it formerly was, we’ll be able to much more efficiently fill orders.”

Tanaka, Miho Imada (president and head brewer of Imada Sake Brewing) and Brian Polen (co-founder and president of Brooklyn Kura) spoke in an online panel discussion Brewers Share Their Insider Stories, part of the Japan Society’s annual sake event. John Gauntner, a sake expert and educator, moderated the discussion and translated for Tanaka and Imada, who both gave their remarks in Japanese. (Pictured from left to right: Gautner, Tanaka, Imada and Polen.)

Recovery Struggles

Japan — which has been slow to vaccinate (only 9% of the population has been fully vaccinated, compared to 47% in the United States) — is currently in a third state of emergency. In the country’s large cities, no alcohol can be served in restaurants. “This is just devastating to the industry,” says Gaunter.

Though sake pubs in smaller metropolitan areas and countryside regions are allowed to be open, few people are out drinking. Many pubs have closed, and others refuse entry to anyone from outside of their prefecture.

“Sales of sake are very seriously affected,” says Imada, one of few female tôji or master brewers. “Rice farmers that grow sake rice are seriously affected as well. If brewers can’t sell sake, they have no empty tanks in which to make sake, so they don’t order any rice and the effects are transmitted down to rice farmers.”

Sake rice is more challenging to grow than table rice because the rice grains must be longer. The amount of sake rice planted in Hiroshima — where Imada Sake Brewing is based — is down 30-40%. Farmers may give up growing sake rice and switch to table rice for good.

The effects of Covid-19 on Japan’s sake brewers will linger into the fall when the next brewing season starts again.

“We cannot really expect a recovery in the amount of sake produced next season, and so therefore production will drop for two years in a row,” she says.

Premium sake brewers with rich generational historys — like Imada Sake Brewing and Rihaku Sake Brewing — are struggling to sell their high-end products.. Department store in-store tastings — a boon to premium sake brewers — have disappeared.

Adapting to Covid

In New York, as pandemic recovery efforts continue, Polen has seen the pent-up demand from consumers. Brooklyn Kura’s retail, on-premise and taproom sales are increasing. After scaling back production and their team in 2020, Brooklyn Kura is now hiring again.

“More importantly, and I think the silver lining out of this, we really needed to redouble our efforts to create a direct line of communication with our best customers,” Polen says.

During the pandemic, Brooklyn Kura launched both a direct-to-consumer business and a subscription service featuring limited-run sakes. “That’s helped us on our road to recovery.”

Imada Sake, too, found ways to improve business. They’re selling bottles and hosting tasting events through their website.

“One of the principles of the Hiroshima Tôji Guild [guild of master sake brewers], the expression is ‘Try 100 things and try them 1,000 times.’ Or in other words the point is keep trying new things and see what contributes towards improvement,” Imada says. “These words convey the spirit of using skill and technique or technology to get beyond difficulties.”

Imada Sake exports 20% of its production; as more countries recover, exports continue to grow. Direct-to-consumer sales, she says, vary and are only constant around Christmas.

Rihaku Sake sells much of their sake to distributors and is seeing international exports increase. They also began direct-to-consumer internet sales, but that channel “didn’t grow as much as I was hoping.”

Consumer Education

France and Italy export billions of dollars of wine a year. Polen argues that sake could be an equally profitable export for Japan. Education and exposure, he says, are the challenge.

“In craft beer and fine wine, a lot of those initial encounters with those products come in places like the tap room in Brooklyn or the wineries in California or the local craft brewery, so creating more of those connection points and initial introduction points in a market like the U.S., having a better facility to distribute sake across the U.S., will help to expand the market, not just to domestic producers but also for the storied producers of Japan as well,” Polen says.

Sake is the national beverage of Japan, and strict brewing laws strive to keep it pure. Japanese sake can only be made with koji and steamed rice. Add hops to it and the drink cannot be called sake legally anymore.

Many sake tôji in Japan are running a multi-generational family brewery.“These craftsmen, who have been brewing sake since they were young, have decades of experience to develop what we call keiken to chokkan or experience and intuition,” Tanaka says, adding that Japan is the only place to buy certain industrial-sized sake making machines such as steamers and pressers. “There’s a lot of advantages that breweries in Japan have. If brewers overseas get too good, this might actually cause problems for brewers in Japan. However, more important than that, I think it’s important for all of us to continue to study how to make better and better sake so everyone around the world can enjoy it.”

Rihaku tries to make their sake recognizable to local consumers who are unfamiliar with the rice wine. Their Junmai Ginjo sake has the nickname “Wandering Poet,” a reference to the famous poet Li Po. Legend says Li Po drank a bottle of sake then wrote 1,000 poems.

“We think a lot about how to get more people that are non-Japanese and outside of the Japanese context excited about sake making and excited about the sake we make,” Polen says. “That includes those folks that are passionate fermenters, like the beer community, that really want to know and learn about things like spontaneous fermentation. So (sake) styles, like yamahai and kimoto, are very easy transition points, very easy talking points for us with that community of brewers and consumers that are really excited to drill deeper into fermentation, especially natural fermentation.”

- Published in Business

A Yeast Primer

Brewers, winemakers and cidermakers are continually on the hunt for the ideal flavor profiles for their fermented beverages. And the key to manipulating those flavors is yeast.

“With beer, you’re taking this kind of gross, bitter soup of sweet barley and hops, and the yeast makes it taste good. Depending on the yeast that gets put in it, it can make it taste like 400 different things, so there’s so much potential there. I think that’s really exciting,” says Richard Preiss of Escarpment Laboratories. Priess was joined by Doug Checknita from Blind Enthusiasm Brewing and Patrick Rue from Erosion Wine Co. to discuss the world of yeast in TFA webinar, A Yeast Primer.

“If you’re invested in vegetable fermentation, yeast might be sort of clouded in mystery and something that is unwanted,” says Matt Hately, TFA advisory board member who moderated the webinar. “It’s what you live by in beverage fermentation in wine and beer and it’s the key to unlocking flavors to make that magic happen.”

Domesticated vs. Wild Yeasts

Just as dogs and cats were domesticated by humans, yeasts have been as well, says Priess, whose company makes and banks yeasts. They are microscopic organisms that adapt, “so if someone’s making beer for over the span of hundreds or thousands of years then the yeast is going to change to kind of get better at fermenting that beer and maybe it’s not going to be so good at surviving out in the wild, just like our toy poodle versus our wolf.”

Other fermented drinks, like wine, sake and cider, use different yeasts with their own specific sets of traits. This is why a wine yeast can’t be used in a beer and vice versa, “though there are some opportunities to experiment.”

Fermenting with wild yeasts has become increasingly in vogue with beer brewers. Aspirational brewers are finding yeasts on the skin of fruit or the bark of trees.

The panelists on the webinar praise experimentation, but note there is risk. Priess says yeasts designed to survive in the wild can be challenging to use in a beer. Checknita points out the safety factor in using yeasts directly from nature as well, “you can get stuff that’s harmful to human health so you have to be careful with your pH levels and what controls there are.”

Traditional winemakers, on the other hand, have long used the wild yeast on grapes to ferment. Rue notes that 10 years ago winemakers began to deviate from this tradition to use pure cultures instead. This process is how many large-scale, industrial producers operate today. But smaller winemakers, who often want to emphasize the specific traits of their terroir, generally use native yeasts and traditional winemaking techniques.

“It’s amazing how wine is how God intended wine to be made because you let nature happen and you’ll probably have a pretty good result with natural fermentation,” Rue continues, “where beer, it’s very touch-and-go, you have to have the perfect conditions and I’ve been able to do spontaneous fermentation with those yeasts.”

The Yeast Family Tree

There’s a large and continually-growing family tree of yeasts, with branches forming for genetic diversity and specialization.

Priess sees three new trends emerging in yeasts: traditional yeasts (like Norwegian kveik) being rediscovered, yeast hybridization (similar to cross-breeding a tomato) and genetic engineering to enhance certain traits of yeast.

“That’s the exciting part of what we’re doing is no one really knows the best approaches to using beer yeast yet, but there’s a lot more new science that’s happening, a lot more brewers that are experimenting, and together we’re collaborating to understand how to work with yeast better and kind of unlock new flavors and new possibilities,” Priess says.

Checknita agrees. He says new yeasts are forming new family trees through spontaneous fermentation, which is taking the base of a beer and experimenting to “push and change those yeasts to do what we want and get that clean flavor that’ll make a beer that tastes good to the human palate.”

- Published in Food & Flavor

New FDA Requirements for Fermented Food

By August, any manufacturer labeling their fermented or hydrolyzed foods or ingredients “gluten-free” must prove that they contain no gluten, have never been through a process to remove gluten, all gluten cross-contact has been eliminated and there are measures in place to prevent gluten contamination in production.

The FDA list includes these foods: cheese, yogurt, vinegar, sauerkraut, pickles, green olives, beers, wine and hydrolyzed plant proteins. This category would also include food derived from fermented or hydrolyzed ingredients, such as chocolate made from fermented cocoa beans or a snack using olives.

Read more (JD Supra Legal News)

Wineries Pivot Without Tasting Rooms

When Black Fire Winery in Michigan began struggling through the pandemic, owner Michael Wells (pictured) had to pivot from a tasting room. “I’ve had to rethink the way I have been doing things. My original business model was to sell out of the tasting room, but now I’m looking to make a huge presence online and outside the tasting room.”

Wells, the first Black owner of a commercial winery in Michigan (and believed to be the only Black commercial winemaker in the state), now sells online in 38 states and is looking to can his beer and hard cider (currently only available in his tasting room). Winemaking is a second career for Wells. He began as a home winemaker, experimenting after coming home from his job with the local fire department. After he retired, he opened Black Fire Winery and now tends to 11 acres of wine grapes.

Read more (Detroit News)

- Published in Business

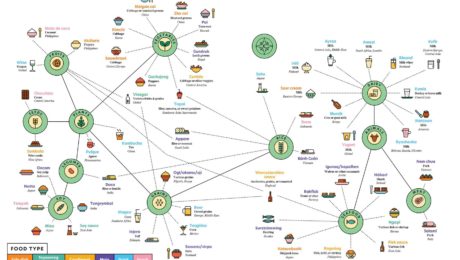

The World of Fermented Foods

In the latest issue of Popular Science, a creative infographic illustrates “the wonderful world of fermented foods on one delicious chart.” It represents “a sampling of the treats our species brines, brews, cures, and cultures around the world,” and is particularly interesting as it shows mainstream media catching on to fermentation’s renaissance. Fermentation fit with the issue’s theme of transformation in the wake of the pandemic.

Read more (Popular Science)

- Published in Food & Flavor

Wildfires Cost California Wineries Billions

Devastating recent wildfires need to spur the California wine industry to invest in researching ways to mitigate the effects of fire and smoke damage. The California Wine Institute partnered with firm BW166 to calculate the cost of the 2020 wildfires to wineries; a $3.7 billion estimate includes loss of property, wine inventory, grapes and future sales.

“At a time of year when vintners would typically be throwing harvest parties and stomping grapes, they were instead faced with mounting uncertainty about the viability of their crop. Many of them decided not to make some or all of the wine that they’d planned to bottle because of the smoke damage. Months later, wineries are still deliberating over those decisions,” writes the San Francisco Chronicle.

Read more (San Francisco Chronicle)

- Published in Business

Begging for Tax Relief for Alcohol

America’s small, craft beer, wine, cider and mead brewers are teaming up with 57 bipartisan senators to ask Congress to extend relief from excise taxes on alcoholic beverage products. These tax cuts, imposed by President Donald Trump in 2017, will expire at the new year.

The coronavirus pandemic has forced “dramatic declines in revenue” because of the closure of on-premise locations. The Beverage Marketing Corporation estimates up to 30% of craft breweries that existed in 2019 won’t make it through the pandemic. And stats by the Brewers Association show craft drinks make up more than 25% of the $116 billion U.S. beer market.

Read more (Food Dive)

- Published in Business

Food and Beverage Laws Passed in 2020

Every year, the nation’s 50 state legislatures pass dozens of new laws that have an impact on fermenters. For example, some states amended alcohol laws to allow drink sampling for craft wineries, while others repealed outdated cottage food laws to help small producers operate and more loosened take-out restrictions to help small restaurants survive the pandemic.

Indicative of this year’s focus on the pandemic, laws were introduced but never debated as lawmakers focused on more pressing issues surrounding the coronavirus. The most common new laws passed in 2020 revolved around helping businesses survive — states called special sessions to aid restaurants, stop price gouging of high-demand products and provide emergency grants to small businesses.

Read on for key food, beverage and food service laws passed this year, most taking effect in 2021.

California

AB82 — Prohibits an establishment with an alcohol license from employing an alcohol server without a valid alcohol server certification.

AB3139 — Establishments with alcoholic beverages licenses who had premises destroyed by fire or “any act of God or other force beyond the control of the licensee” can still carry on business at a location within 1,000 feet of the destroyed premise for up to 180 days.

Delaware

HB 237 — Eliminates old requirements that movie theaters selling alcohol must have video cameras in each theater, and that an employee must pass through each theater during a movie showing.

HB275 — Permits beer gardens to allow leashed dogs on licensed outdoor patios.

HB349 — Permits any restaurant, brewpub, tavern or taproom with a valid on-premise license to sell alcoholic beverages for take-out or drive through food service, so long as the cost for the alcohol did not exceed 40% of the establishment’s total sales transactions.

Hawaii

SR84 — Creates a Restaurant Reopening Task Force to help restaurants in Hawaii safely reopen that were closed during the COVID-19 pandemic.

SR94 — Urges restaurants to adopt recommended best practices and safety guidelines developed by the United States Food and Drug Administration and National Restaurant Association in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Idaho

HB343 — Amends existing law to require licensing to store and handle wine as a wine warehouse.

HB575 — Allows sampling of alcohol products at liquor stores, which was formerly forbidden under law.

SB1223 — Eliminates obsolete restrictions on food products, to match federal standards. It repeals requiring extra labels on some imported food products, and repeals using enriched flour in bread baking.

Illinois

HB2682 — Amends Liquor Control Act of 1934. Allows a cocktail or mixed drink placed in a sealed container at the retail location to be sold for off-premises consumption if specified requirements are met. Prohibits third-party delivery services from delivering cocktails or mixed drinks.

HB4623 — Amends Food Handling Regulation Enforcement Act, regulating that public health departments provide a certificate for cottage food operations, which must be displayed at all events where the licensee’s food is being sold.

Iowa

HB2238 — Amends code regarding food stands operated by a minor. Bans a municipality from enforcing a license permit or fee for a minor under the age of 18 to sell or distribute food at a food stand.

Kentucky

HB420 — Implements Food Safety Modernization Act, authorizing a department representative to enter a covered farm or farm eligible for inspection.

SB99 — Amends alcohol laws for state’s distillers, brewers and small wineries. Eliminates the sunset on local precinct elections to grant distilleries, and allows distillers to sell other distiller’s products.

Louisiana

HR17 — Allows third-party delivery services to deliver alcohol.

HB136 — Makes adulterating a food product by intentional contamination a crime.

SB455 — Increases the size of containers of high-alcoholic beverages.

SB508 — Gives restaurants protection from lawsuits involving COVID-19. The public will be unable to sue restaurants for COVID-19-related deaths or injuries, as long as the restaurant complies with state, federal and local regulations about the virus.

Maine

LD1167 — Encourages state institutions to serve Maine food and Maine food products, increasing the visibility of the state’s local food producers.

LD1884 — Amends current laws regarding businesses that hold dual liquor licenses, which authorized retailers to sell wine for consumption both on- and off-premise. Retailers with the dual license can now sell with just one employee at least 21 years of age present, and adds that wine can be sold for take-out if food is part of the transaction.

Maryland

HB1017 — Allows cottage food businesses to put their phone number and business ID on their food label, rather than their address as currently required by the Maryland Department of Health.

SB118 — Expands definition of “alcohol production” and “agricultural alcohol production.” The new definitions aim to give Maryland farmers and producers the ability to sell beer, wine and spirits to increase agritourism.

Massachusetts

SB2812 — Expands alcohol take-out and delivery options during COVID-19 pandemic. Allows restaurants to sell mixed drinks in sealed containers alongside other take-out and delivery food orders.

Michigan

HB5343 — Revises regulations on brewpubs and microbreweries, increasing the quantity of beer a microbrewer is permitted to deliver to a retailer during a year from 1,000 barrels to 2,000 barrels.

HB5345 — Amends the Michigan Liquor Control Code to delete the Michigan Liquor Control Commission (MLCC) $6.30 tax levied on each barrel of beer manufactured and sold in Michigan.

HB5354 — Amends the Michigan Liquor Control Code to delete the requirement that a brewpub cannot sell beer in Michigan unless it provides for each brand or type of beer sold a label that truthfully describes the content of each container.

SB711 — Establishes new limited production brewer license for microbreweries at cost of $1,000 for license.

HB5356 — Amends the Michigan Liquor Control Code to ban the required $13.50 cent-per-liter tax on all wine containing 16% or less of alcohol by volume sold in Michigan.

Minnesota

HB5 — Authorizes emergency, small-business grants and loan funding for businesses affected by COVID-19.

HB4599 — Extends period of mediation for Minnesota farmers suffering economic difficulties to keep their farm.

Mississippi

HB326 — Amends outdated code to increase the maximum annual gross sales for a cottage food operation (from $20,000 to $35,000) before the producer would need to pay food establishment permit fees. Authorizes a cottage food operation to advertise products over the internet.

New Jersey

AB2371 — Requires large generators of food waste (like restaurants and supermarkets) to recycle food garbage rather than send it to incinerators or landfills.

AB3865 — Limits return of food from retail food stores during a public emergency.

SB864 — Prohibits sale of single-use plastic carryout bags, single-use paper carryout bags and polystyrene foam food service products, and limits single-use plastic straws.

SB1591 — Allows alcoholic beverages to be consumed from open containers in the Atlantic City Tourism District.

SB2437 — Limits service fees charged to restaurants by third-party food takeout and delivery applications during COVID-19 pandemic.

New Mexico

SB3 — Enacts the Small Business Recovery Act of 2020, which provides loans for small businesses suffering during the coronavirus pandemic.

New York

SB8225 — Authorizes issuing a retail license for on-premise consumption of food and beverage within 200 feet of a church, synagogue or other place of worship.

AB8956 — Allows a licensed brewery or farm brewery to provide no more than four beer samples not exceeding four fluid ounces each.

SB1472 — Requires hospitals to offer plant-based food options to patients upon request.

SB7013 — Authorizes the manufacture and sale of ice cream or other frozen desserts made with liquor.

North Carolina

SB290 — The Alcoholic Beverage Control Regulatory Reform Bills, it allows distilleries the same serving privileges as wineries and craft breweries and reduces regulation on out-of-state sales.

Ohio

HB160 — Aid for the restaurant industry to recover from COVID-19 pandemic, the bill doubles the maximum number of Designated Outdoor Refreshment Areas (DORAs) that can be created in a municipality or township. Also allows Ohio’s small wineries to sell prepackaged food without regulation from the Ohio Department of Agriculture, creates bottle limits for micro-distilleries and permits license holders to sell alcoholic ice cream.

South Carolina

HB4963 — Amends state alcohol code, allows licensed retailers to give wine samples in excess of 16% alcohol, cordials or distilled spirits, as long as they don’t exceed a total of three liters a year.

SB993 — Amends state alcohol code to allow a permitted winery to be eligible for a special permit to sell wine at off-premise events. Also increases the amount of beer a brewery can sell to an individual per day for off-premise consumption.

South Dakota

HB1073 — Authorize special event alcohol licenses for full-service restaurant licensees.

HB1081 — Allows colleges to teach brewing beer and wine classes on South Dakota campuses to students age 21 or older. Brewing must be held off campus as the education institution is not deemed a licensed manufacturer. Any distilled spirits, malt beverage, or wine produced under this section may only be consumed for classroom instruction or research and may not be donated or sold.

Tennessee

SB2423 — Allows alcohol sales at the Memphis Zoo.

SB1123 — Encourages farmers who produce raw milk to complete a safe milk-handling course.

Utah

HB134 — Legalizes the sale of raw butter and raw cream in Utah;

HB232 — An agri-tourism bill that allows farms and ranches to host events that include food that would not need to be prepared in a commercial kitchen. Farmers must apply for a food establishment permit to use their private home kitchen.

HB399 — Changes to the Alcohol Beverage Control Act, prohibits advertising that promotes the intoxicating effects of alcohol or emphasizes the high alcohol content of an alcoholic product.

HB5010 — The COVID-19 Cultural Assistance Grant Program, which appropriates $62 million for struggling arts, cultural and recreational organizations and businesses across the state.

HB6006 — In response to the coronavirus pandemic, the bill amends the Alcohol Beverage Control Act, delaying the expiration date of the retail licenses set to expire in 2020 for places selling alcohol. Also permits alcoholic beverage licensees at international airports to change locations if needed.

Vermont

SB351 — A coronavirus relief bill which authorizes $36 million for agriculture and forestry sectors.

Washington

HB2217 — An update to Cottage Food Law eliminates the requirement that a home address must be put on a food label.

HB2412 — Increases amount of additional retail licenses for a domestic brewery or microbrewery from two to four, and directs health department to adopt rules allowing brewery owners to allow dogs on brewery premise

SB5006 — Allows sale of wine by microbrewery license holders.

SB5323 — A bill eliminating single-use, plastic carry-out bags

SB5549 — Modernizing resident distillery marketing and sales restrictions. Allows distilleries to sell products off-premise, similar to breweries and wineries.

SB6091 — Continues work on the Washington Food Policy Forum, including support for small farms and increasing the availability of food grown in the state.

West Virginia

HB4388 — Removes outdated restrictions on alcohol advertising, limiting the Alcohol Beverage Control Commissioner’s authority to restrict advertising in certain advertising mediums, such as at sporting events and highway billboards.

HB4524 — Making the entire state “wet,” permitting the off-premises sale of alcoholic liquors in every county and municipality in the state.

HB4560 — Permits licensed wine specialty shops to sell wine with a gift basket by telephonic, electronic, mobile or web-based wine ordering. Establishes requirements for lawful delivery.

HB 4697 — Removes restriction that a mini-distillery use raw agricultural products originating on the same premises

HB4882 — Allows unlicensed wineries not currently licensed or located in West Virginia to provide limited sampling and temporary, limited sales for off-premise consumption at fairs, festivals and one-day nonprofit events “in hopes that such wineries would eventually obtain a permanent winery or farm winery license in West Virginia.”

Wisconsin

HB1038 — Bans customers from returning food items during a health pandemic or emergency, dissuading people from stocking up on too many supplies.

SB83 — Increases sales volume of alcohol by retail stores from four liters per transaction to any quantity.

SB170 — Allows minors to operate temporary food stands without a permit or license.

Wyoming

HB82 — Authorizes a microbrewery to operate at more than one location. The local licensing authority may require the payment of an additional permit fee not to exceed $100.00.

HB84 — Authorizes the sale of certain homemade food items that do not require time or temperature control. These include but are not limited to:

but is not limited to, jams, uncut fruits and vegetables, pickled vegetables, hard candies, fudge, nut mixes, granola, dry soup mixes excluding meat based soup mixes, coffee beans, popcorn and baked goods that do not include dairy or meat frosting or filling or other potentially hazardous frosting or filling;

“non-potentially hazardous” (no dairy, quiches, pizzas, frozen doughs, foods that require refrigeration and cooked meat, cooked vegetables and cooked beans). Allows someone other than the producer to sell the food, as long as food is not sold in a retail location or grocery store where similar food items are displayed or sold. Food must be labeled with “food was made in a home kitchen, is not regulated or inspected and may contain allergens.”

HB158 — Allows microbreweries to make malt beverages at multiple locations rather than one as deemed in current law.

Q&A with Chris White, White Labs

As a biochemistry grad student with a penchant for homebrewing, Chris White never thought his growing collection of yeast strains would amount to anything outside a hobby. But when White graduated with his PhD and was offered a lucrative job in the biotech field, one caveat kept him from accepting the offer — there were no side jobs allowed.

“I never had some big plan to start a company. But I liked all the fermentation stuff I was doing and didn’t want to let go of my yeasts,” says White, CEO and founder of White Labs. “I said no to the job, and from there White Labs kept going and going and getting bigger and bigger.”

Today, White Labs is a powerhouse in the fermentation industry. They provide professional breweries with liquid yeast, nutrient blends, educational classes, analytic testing and private consulting.

White Labs is celebrating a landmark 25th anniversary this year, despite a global pandemic that has shuttered breweries. They have released their own line of beer, created a new nutrient blend for hard seltzer brands, began a YouTube series and launched free how-to education classes for homebrewers. White Labs will host a year in review webcast on Dec. 9.

“We’ve had a lot of success and we’ve made a lot of mistakes, and we’ve tried to learn from those mistakes. But we’re a team. And we really got lucky that we hired people interested in fermentation that helped build this company,” White says. “Everyone really pulled together during COVID and did whatever was needed. It’s been a great experience because we had solutions and we had teamwork. And I think it’s taken 25 years to get to that team, that tribe.”

A yeast guru, White is a co-author of the book “Yeast: The Practical Guide to Beer Fermentation.” Below, check out our Q&A with White.

The Fermentation Association: You studied biochemistry at University of California, Davis, then got your PhD in biochemistry at University of California, San Diego. What made you decide to dive into yeasts?

CW: I was always interested in science since high school chemistry, and then in college was interested in how cells work, how DNA worked. It drove me to where I am today, really. Most people I went to school with at UC Davis, they were studying biochemistry to be a physician. But that’s not what I wanted to do, I was more interested in biotech and grad school.

Meanwhile, I was homebrewing. It was a great combination of things that happened. The science and homebrewing is what led me to put that together and make yeast for homebrewing, then yeast for craft brewing.

TFA: Is that what led you to start White Labs?

CW: It really was. I like beer. I was fascinated with how it could be made. It’s pretty simple to make beer — simple, but not easy. It’s difficult to make a great beer. But it’s fairly simple since it’s only four ingredients if you include the water. That’s what’s great about a lot of fermentation, the raw materials are all around you. They’re simple. Making it taste good is the hard part, that’s the art of it. I liked beer, I really got into homebrewing, then the people I was making homebrewed beer with started a store in San Diego, Home Brew Mart, in 1992. We became friends and that’s who I was homebrewing with every weekend. Then my friend from the store said “Hey, we need yeast,” and I started a little company on the side to make yeast. It wasn’t like I had some big plan to start a company, I thought I’d just make a little each week. And then other people asked and other people asked. By the time I got closer to finishing grade school, I just didn’t want to stop doing the yeast for brewing.

TFA: Now there are over 1,000 strains of yeast in the White Labs yeast bank. Tell me about it.

CW: We have a yeast bank that I spent a lot of time building in the beginning, more for my own brews, but obviously later on, it became more and more. The foundation of our company is our yeast strains and the way we store them. We’re collecting strains all the time. But what I did in the beginning was collect different strains from travel, from different yeast banks. We created our own private yeast bank at White Labs, but there are yeast banks around the world. Especially in Europe where brewing really began in an industrial way and where yeast was discovered and started to get collected. There’s a great yeast bank in Denmark, Germany, the UK. I spent a lot of time acquiring strains from those.

You get to know the yeast in a different way, the strains, what they do. Performance, conditions. But for beer especially, it’s really how they taste, which is so important. We only make those flavors through fermentation. We still continue to acquire strains. People send them to us, we bank private strains for companies, sometimes they buy them in a liquid form we make for them, sometimes we just store it for them. But usually, they’re banking it for us to make something with it.

TFA: Besides yeast, White Labs offer testing services as well.

CW: White Labs Analytical Lab is really separate in the fact that a lot of people that work in that lab don’t really have anything to do with the yeast. It’s just testing samples. They’re usually fermented beverages. Yes, there’s beer there, but that’s just a part of White Labs Analytical Lab. There’s the spirits that come for testing, kombucha, cider, mead, any kind of commercial business making a fermented beverage that needs some kind of testing. Sometimes it’s regulatory for export. Sometimes it’s just for their own data, like actual alcohol by volume instead of calculated, sometimes it’s microbiology or tracking down a problem or contamination. It’s all confidential, like everything at White Labs. But we get to work with a lot of cool companies, a lot of them may not get yeast from us, that’s really not a requirement. The yeast and testing run separate.

TFA: Have you seen kombucha brewing grow?

CW: Oh yeah. Originally, that’s how we got into analytical testing because people were asking for alcohol lab evaluations, which is so important in kombucha. We all know what happened there (Whole Foods pulled all kombucha bottles off shelves in 2010 after several brands tested at higher alcohol beverage levels then what was printed on the bottles). And it happened because it’s a biological process. You put that thing in a bottle and it’s going to keep fermenting. People had to really try to figure out what to do with that. So a lot of alcohol testing, and a lot of that is regulatory in kombucha.

But then we started making SCOBYs because a couple of our staff got really into it. Just like I started making yeast in my own home brewing, they started making SCOBY in White Labs for their own kombucha making. So we said “Let’s sell it.” And now we make a bunch of it.

TFA: That’s forward-thinking, expanding your offerings to all fermented drink products.

CW: Yeah and the different facilities allow us to do different things. We grow all the SCOBYs in North Carolina because it was a new facility at the time and had the space, San Diego is full.

TFA: White Labs released their own canned beer in July. Tell me about it.

CW: A lot of the things that came out of this year really were not new ideas, like canning. Someone gave a presentation at White Labs during one of our internal innovation summits that’s open to anyone in the staff about canning beer. But during this time of COVID, when we’re not focusing on growth, we were able to work on a lot of those projects and really build a better company. Once we gave up the idea that revenue is not going to go up right now, we worked on other things. And it’s been great. A lot of cool things have been coming out of our teamwork this year, and one of those was canning.

So we said let’s do that because we’re not selling beer in our tap room — we’ve got a tap room in San Diego for White Labs Brewing Company and a kitchen and tap in Asheville, it’s more of a full restaurant. We weren’t selling a lot of beer and we have a lot of beer, so why not can it? We have done three different beers now in cans. The IPA, a hazy IPA and the pilsner. And we’re going to do another lager and IPA next month. It’s been fun for the brewers to be able to brew it. I think it’s been a nice boost for everyone in the company, not even money wise, just to have another milestone: we put our beers in cans. It’s a nice billboard for the brewery. And they get to have fun with graphics, and how to tell our story, and really share what we’re doing in the tap rooms.

People are amazed that it’s the same beer, same exact batch but put into smaller fermenters and pitched with two different yeast strains. They say “Wow, you created different flavor beers? They taste different?” Yeah, because that’s fermentation. Fermentation makes these flavors and when people taste that it’s the same exact beer made with two different yeast strains, they get it in 30 seconds. “Oh that’s what a yeast does?” But you have to come to our tap room to experience that. And obviously during these times, you can’t come to the tap room. But canning is a way to share that with people outside the tap rooms.

TFA: Who buys more yeast from White Labs — commercial producers or homebrewers?

CW: Commercial because of volume. But we’re available for everything in homebrew. We try to mirror every test, every yeast strain, and make those available for home brewing because that’s our roots and I think it’s important. There’s been growth in home brewing during COVID. People at home with a hobby are buying yeast. That’s kind of nice, I like to see that.

TFA: Craft brewing has been hit so hard by pandemic. What have you seen your clients doing to survive?

CW: They’re getting creative. People had to figure out the to-go thing, first of all. That maybe involved buying software or creating a new website. Each company I talk to, regardless of what industry, they had to do something technology wise. Very few could close the bar door and were all set up to sell everything through the warehouse.

I think customers were also really good about supporting local businesses, wanting to help them. There’s been a lot of to-go. But it still doesn’t compare to all the beer they could sell, all the stuff that gets sold through bars. Even if one little meadery sells more to go, it doesn’t replicate all the tap room business that just disappears.

TFA: What do you think is the future of the fermented drink industry?

CW: It’s up to them. We pay attention so we can be there to help. But really these things come from creative people. New things have to come out. That keeps the industry growing. And I don’t know what those new things are, but we try and pay attention.

I think transparency and honesty is a hallmark of fermentation industries — whether craft breweries or wineries — and I hope that stays. That’s been a big part of the trust with consumers, and the fact that you can do these things at home too, so you know how it’s done. And with new techniques or things that get introduced, I think the industry needs to keep the transparency part of the business. Because fermentation being such an old, old method — a lot of people would like to replace fermentation with something else. They say “Let’s just mix these things together rather than do that weird fermentation.” But weird fermentation is what makes it so special.

- Published in Business, Food & Flavor