The olive oil, wine and beer industries each create an enormous amount of waste. Producers, vintners, and brewers dispose of millions of tons of pomace and spent grains every year, often at a big cost.

To a crowd of food industry professionals at Natural Products Expo West, professors at University of California, Davis, shared their research into how these byproducts can be upcycled.

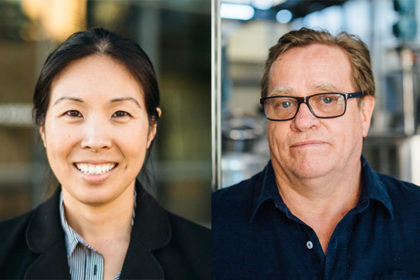

“There’s a lot of waste that can be generated doing agriculture and food processing,” said Selina Wang, PhD, Cooperative Extension Specialist in the Food, Science and Technology department. Globally, good waste is estimated at 140 billion tons a year. “That is a lot, but also a lot of opportunities for us to explore.”

Olive Oil Waste

Wang, who researches small-scale fruit and vegetable processing, says olive oil needs a byproduct solution. Oil is only 20% of an olive’s weight – the other 80% is discarded in olive oil production. Globally, the industry generates 20-30 million tons of olive pomace a year.

What industry, Wang questions, would operate using only 20% of their commodity?

“This is an industry that has been made to use the minor product. But we know there’s a lot of values in the byproduct,” Wang says. Olive pomace has numerous active health compounds which, when consumed, are proven to prevent disease like cancer, Type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease. But disposing of this byproduct creates a large carbon footprint. “Can we have a solution to climate change while at the same time improving our health?”

Many producers use the waste as animal feed, giving it away to ranchers. But often, the cost of transportation is too high to justify the benefits. And using olive pomace for compost is not ideal, as it has a negative effect on soil microbes.

In a recent UC Davis study, olive pomace was added to pasta, bread and granola bars, which were then tested for consumer acceptance. Tastes were strong and the grains turned purple when the pomace was added, so the amount of pomace added was low (7% in the pasta and 5% in the bread and granola bars). Consumers didn’t hate the products – they liked them slightly less than the unfortified versions – but the majority said they wouldn’t pay more for the items made with olive pomace.

“I would challenge us to think outside the status quo,” Wang says. “Olive oil was an industry developed with tradition, love and passion. But does it make sense to have an industry where we’re using only 20% of raw material? Or do we actually have an industry focusing on the 80% and the 20% is a wonderful gift we give to family and friends?”

Grape Waste

Further UC Davis studies are also looking at wine byproducts The global wine industry produces 10-13 million tons of grape pomace annually.

That waste is rich in flavonoids and oligosaccharides. UC Davis and Iowa State are currently studying the flavonoids as natural antioxidants and the oligosaccharides as prebiotics, and if they would have a synergetic effect on gut health.

“It basically shows there’s a second life to winemaking and the wine byproduct that’s generated,” she said.

Researchers at UC Davis who have studied feeding cows seaweed to reduce greenhouse gas emissions have proposed to the California Research Dairy Foundation that they use grape pomace instead. It’s cheaper than seaweed and cows burp less after consuming grapes.

Other industries, such as cosmetics, pet food and construction, could also use the byproducts. For example, a new study shows how construction companies could use olive pomace in asphalt paving and building materials.

Brewing Waste

Waste streams are an even bigger problem for the brewing industry, says Glen Fox, PhD, the Anheuser-Busch endowed professor of Malting and Brewing Science at UC Davis. Brewers globally produce over 49 million tons of spent grain a year.

That waste is high in water content (about 80%), but most brewers don’t have the ability to store wet grain. Similar to olive and grape pomace, it’s cheap feed for animals. But the cost of transporting spent grain outweighs the benefits for most breweries.

“At the moment, they’re giving it away,” he says. “They would like to get something back for it.”

Fox sees big opportunities for food producers to use brewing grains, which are packed with nutrients. Compounds can be extracted, such as dietary fiber for supplements, hydrocinnamic acid for makeup and even cellulose pulp for toilet paper. Fox is working on a patent for a process that would allow grains to be applied directly to soil.

The craft brewing industry is “the most viral business in America,” Fox said. There are breweries everywhere – some 9,000 craft brewers in the U.S., with over 1,000 in California alone. But there are not nearly as many food production facilities that can collect the spent grains.

“This industry is in an advantageous position because it has that waste stream every day,” Fox says. “If you want to potentially use this in your business, you don’t have to look far for your supplier.”

When Will the Food Industry Innovate?

“We have to start rethinking our food systems – farm to mouth,” Fox said. “It’s a big challenge.”

There’s no shortage of high-quality research on options for olive oil, wine and beer byproducts, Wang points out. The food industry needs to innovate profitable, desirable products made from upcycled ingredients. At one point whey – a byproduct of cheese production – was dumped down the drain, Wang said. Now it’s a popular protein supplement, in powders and bars.

Two brands are making inroads. Vine to Bar uses grape pomace to make chocolate. ReGrained uses spent beer grains to make pastas, bars and puffs.

“The key is we need to go from a linear economy – which is just made to waste – to a circular economy where we can avoid generating these wastes by upcycling every waste or every byproduct that we generate,” Wang said.