Miso: Traditional Flavors with Modern Application

Chefs and home cooks are using miso in innovative ways, experimenting with contemporary dishes inspired by traditional Japanese techniques.

“It’s becoming pretty ubiquitous in people’s kitchens now. It’s been a great creative outlet for people trying different misos,” says chef Kyle Connaughton. He joined chef-author Hiroko Shimbo and chef-educator Kirsten Shockey in a TFA webinar organized and moderated by chef (and TFA advisory board member) Robert Danhi Miso: Traditional Flavors with Modern Application.

Connaughton uses Saikyo miso as a salt and seasoning in the kitchen at SingleThread, enhancing the natural flavor of the vegetables and meat used in the 11-course tasting menu. SingleThread is a three-Michelin-starred restaurant, inn and 24-acre farm Connaugthon opened with his wife, Katina, in Healdsburg, California.

“I think chefs and food companies will continue to innovate in new ways and new directions because there are benefits that come way beyond creating a trendy dish,” Connaughton says. Using miso instead of dairy creates a less fatty, more nutritious dish, and miso can be used as a more sustainable substitution for less environmentally-friendly ingredients.

SingleThread’s culinary style is inspired by Japan (where Connaughton lived and trained for years) mixed with the local terroir of California’s wine country. Miso is used frequently , and he shared pictures of “how we go beyond miso soup and miso ramen.” Dishes included a roasted pumpkin puree with miso as a cream base instead of milk, duck liver parfait cured in miso, porridge made with wagyu beef and caramelized miso and a chocolate ganache made by blending in miso for extra umami flavor.

Shimbo, a world-renowned authority on Japanese cooking and author of “Hiroko’s American Kitchen,” showed off miso-based dishes from her home kitchen. These included different miso soups, a pastry where miso is mixed in with the flour and a pizza topped with a miso-based tomato sauce.

“Miso culture in Japan is diverse and wonderful,” Shimbo says. There are 16 miso techniques in Japan, each flavor originating from a different region in the country. “This extended geography with associated climate variations contributes to creating regionally unique food culture.”

Miso can vary in sweetness, aroma, saltiness, uses and production processes. Shimbo detailed the flavor, culinary tradition and modern applications of three types of miso: Sendai, Saikyo and Mugi.

“Not all the miso sold at the food stores are made equally or worth purchasing,” she adds. Miso made at the factory level can be cheap, with alcohol added to stop the fermentation. “We can’t expect food flavor or nutritional value in this type of miso.”

Kirsten Shockey, author of “Miso, Tempeh, Natto & Other Tasty Ferments” (and TFA advisory board member) agreed with Shimbo. When purchasing miso, study the source. Unpasteurized miso will provide the most benefits. Shockey studies the traditional uses of any ferment, and says miso should never be cooked beyond 140 degrees because it will kill the nutrients. In Japanese kitchens, miso soup is never brought to a boil.

“The knowledge of the people who were using these foods forever is also important,” Shockey says. “Think about how they’ve been used to keep people very nourished through centuries.”

Shockey shared different types of colorful miso pastes from her home kitchen. She also let viewers peek inside her 5-gallon cedar vat, where she makes long-aged batches of miso.

“Miso is this beautiful collaboration of microbes, enzymes, time, and all of this acting upon grains and legumes. And it creates something super delicious and, in a lot of ways, more than the sum of its parts,” Shockey said. “Miso is magical…I think of it as a top-level ferment because everybody’s involved, all the microbes.”

- Published in Food & Flavor

Retail Sales Trends for Fermented Food and Beverage

Kimchi, fermented sauces and tempeh are driving growth in the fermented food and beverage category, a $9.2 billion industry that’s grown 4% in the last year.

“We’re excited about the growth potential for fermented food. While fermented food represents about 1.4% of the market today, there are segments that are tracking well above the growth of food and beverage [overall] that are poised for disruption in the future,” says Perteet Spencer, vice president of strategic solutions at SPINS. Spencer shared this information in a recent webinar hosted by The Fermentation Association. “There’s a ton of opportunity to scale and increase the footprint of these products.”

SPINS spent weeks working with TFA to define the fermentation industry’s sales, drilling into 10 fermented product categories and 57 product types. Wine, beer and cheese sales were excluded from the data — those categories are very large, and would obscure trends in smaller categories. (All three are also well-represented by other organizations.)

Pickles and fermented vegetables “is a space that’s seen [a] pretty explosive uptick in growth over the past year,” Spencer says. Every segment is growing — kimchi, sauerkraut, beets, carrots, green beans, sliced and speared pickles and all other vegetables — with pickles the largest, nearly 60% of the category.

The biggest growth, though, is coming from products other than pickled cucumbers. Kimchi is at the center of numerous consumer retail trends. Consumers are purchasing healthier food made with fewer ingredients, and they want food with international flavors. Kimchi makes up only 7% of the category, but sales are increasing at an explosive 90% growth rate.

More people are experimenting with fermenting while they’re at home during the coronavirus pandemic, but these kitchen DIYers do not appear to be detracting from sales.

“The more people make fermented foods, they appreciate what’s available in the store that maybe didn’t exist five or 10 years ago,” notes Alex Lewin, author and TFA advisory board member who moderated the webinar. “Anyone who has made kimchi knows it takes a lot, it makes a big mess, you get red pepper powder stuck under your fingernails and onion in your eyes. I can make kimchi (at home), and then once I’ve made kimchi, I’m like ‘Ok, maybe next time I’ll buy it.’”

Fermented sauces are also growing, up 24% in 2020. The largest segment in sauces is, of course, soy sauce, almost 85% of the category. But gochujang, less than 2% of the category, is increasing at over a 56% growth rate.

Versatility is helping sauces, pickles and fermented vegetables, Spencer says. Any food product with multiple uses is selling well. The condiments and sauces can be used as a topping on eggs, hamburgers or pizza, or mixed-in a salad, rice dish or soup.

Sake, plant-based meat alternatives and miso had combined annual growth of $75 million in 2020. Sake grew 16%, and both plant-based meat alternatives and miso each grew 26%.

Yogurt and kombucha still dominate the fermented food and beverage market. Yogurt is 81% of the market; if yogurt is removed, kombucha is 51% of the remainder.. Both have experienced slowdowns in sales from their peaks. Kombucha sales have slowed recently, as grab-n-go opportunities have shrunk during the pandemic.

Yogurt giant brands Chobani, Yoplait and Dannon still dominate the category, as do GT Kombucha, Health-Ade and Kevita reign for kombucha.

Spencer notes the 4% growth rate of fermented products overall would be higher without yogurt. It’s a large category that — despite an uptick in 2020 during the pandemic – has been fairly flat in recent years. Core (traditional) yogurt has been growing at a 1.6% rate; Greek yogurt, at about twice that pace. Those two segments account for roughly 80% of the category.

“This is an opportunity for disruption for emerging brands,” Spencer says. “We’re already seeing some of the legacy segments start to get disrupted by new innovation, so I’m excited to see the evolution of that innovation and where that goes and kind of what opportunities peek out of that.”

“Overall, we’re seeing historically small segments gaining traction in the marketplace,” Spencer adds. “The pandemic has brought a renewed consumer focus on the fermented space.”

Though fermented products have an added healthy benefit, customers are looking for delicious flavor first.

“In these fermented categories we covered today, taste first is always really important. I think people are going to these categories for different taste experiences,” Spencer says. “If you can level up with a functional benefit, that’s fantastic, but we have to balance the taste first. If it’s highly functional but doesn’t taste good, it just doesn’t have the same success.”

- Published in Business

Fermentation as Metaphor: A Conversation

Fermentation is more than just a food processing technique. Sandor Katz, today’s “godfather of fermentation,” expounds on the metaphorical significance of fermentation in his new book “Fermentation as Metaphor.”

“Fermentation is such a fascinating lens through which to look at the world and the incredible practicality of traditional cultural wisdom,” says Katz, fermentation author and educator, during a webinar hosted by The Fermentation Association. “In the English language, there’s a long tradition of describing things as fermenting that are not foods and beverages. We talk about a period of great musical fermentation, artistic fermentation, political fermentation, culture fermentation, we’ve applied it very widely. This book is really an exploration of that and a reflection of that.”

Katz spoke with his friend Mara King, chef and food professional, and they shared thoughts on how fermentation can be an unstoppable force for change.

“Fermentation is really teaching the world to embrace weird and funky things,” King says. “Take natural wines as an example. There’s a big movement in the world of wine making for using older techniques, using less chemical filtration and clarification methods. What you’re left with is a product that changes year to year and a product that has subtle notes of animal or leather, things you wouldn’t find before. We’re realizing a little bit of horrible is quite wonderful.”

Until the 19th Century, all wine was natural, Katz points out. Winemakers relied on organisms on the skins of the grapes for the flavor. Beer used to be a similarly natural product, but that’s changed as brewers today add yeast strains.

“It’s so much more interesting and complex of a flavor than the mass-produced beer where just a single organism is introduced. Fermentation really encourages people to expand their palates,” Katz says. “Funk is good. Funk makes things interesting. Funk is complexity. What I’ve learned by working with fermented tofu in food, working with natto in food, working with sumbala, the West African condiments that are natto-like, working with fish sauce, is [these ingredients on their own] might taste awful to you, but a little bit can introduce this je ne sais quoi into the flavor of a dish. Complexity is good and even flavors on their own that people might find scary or intimidating.”

The photography featured in “Fermentation as Metaphor” is unique — magnified microbes used in the creation of fermented food and drink. The images, captured with a scanning electron microscope, show the complexity of these microorganisms. Each structure is supported by a smaller structure, with membranes that are highly permeable.

“There continues to be a magic to fermentation, maybe in some ways even more so as fewer people have direct contact with their food. As there’s less wine making, cheese making, [or] baking in our lives that people actually see, these processes become more and more mysterious. [Mystery] has always been an aspect of fermentation because, until very recent times, there was never a clear, rational scientific understanding of what is going on. They were always seen as divine processes with lots of ceremony and ritual attached to them,” Katz adds. “Fermentation takes this neutral, plain food and gives it this really discernable, compelling flavor.”

Katz is already working on his next book, a fermentation travelogue book highlighting what he’s learning about fermentation in his worldwide travels. Katz and King previously filmed a series “The People’s Republic of Fermentation,” sharing the fermentation traditions of southwest China. They were supposed to travel to Taiwan and eastern China earlier this year, but the trip was cancelled due to the coronavirus pandemic. Next on Katz’s “to do” list — exploring the fermented cuisine of West Africa.

For anyone interested in purchasing “Fermentation as Metaphor,” visit Amazon or Bookshop.

- Published in Food & Flavor

Farmer, Nutrition Activist Uses Fermentation Methods to Create Healthier School Lunches

An organic farmer and nutrition activist is teaching schools and daycare centers in Japan to grow their own vegetable garden using fermented compost from recycled food waste, then incorporate into school lunches those fresh vegetables with traditional Japanese fermented foods (like miso and pickles). Two years after the program’s launch, absences due to illness have dropped from an average of 5.4 days to 0.6 days per year.

Farmer Yoshida Toshimichi “is a devout believer in the power of microbes.” Using centuries of Japanese folks wisdom that is supported by modern science, Toshimichi explains that fermentation bacteria in the compost yields hardy, insect-resistance vegetables. He says the key to a healthy immune system is maintaining a diverse and balanced gut microbiota. “Lactobacilli and other friendly microbes found in naturally fermented foods can help maintain a healthy environment in the gut, just as they do in the soil,” continues the article. Microorganisms in fermented foods like miso and soy sauce will help balance gut flora. “Organic vegetables, meanwhile, provide the micronutrients and fiber on which those friendly bacteria thrive. In addition, phytochemicals found in vegetables—especially, fresh organic vegetables in season—are thought to guard against inflammation, which is associated with cancer and various chronic diseases,” the article reads.

Toshimichi has authored books on his farming and nutrition practices and is featured in the two-part documentary film “Itadakimasu,” which translates to “nourishment for the Japanese soul.”

Read more (Nippon)

- Published in Food & Flavor, Health, Science

Study: Eating Higher Amounts of Fermented Soy Products Reduces Mortality Risk

A Japanese study published in the British Medical Journal found that people eating higher amounts of fermented soy products (like miso and natto) reduce their mortality risk. Participants with the highest intakes of fermented soy had a 10% lower risk, compared with those who had the lowest intakes. For participants who ate a lot of soy products that were not fermented, no significant association was found between intake of soy products and mortality rate.

Read more (British Medical Journal)

- Published in Science

Fermented Foods Again Top Superfoods List

For the third year in a row, fermented foods tops Today’s Dietitian list of the year’s No. 1 superfood. The annual “What’s Trending in Nutrition” survey reveals the hottest food and nutrition trends to look for in 2020.

“The 2020 survey results send a clear and consistent message. Consumers want to live healthier lives,” says Louise Pollock, president of Pollock Communications. “They have access to an incredible amount of health information, and they view food as a way to meet their health and wellness goals. Consumers are taking control of their health in ways they never did before, forcing the food industry to evolve and food companies to innovate in response to consumer demand.”

Consumers are using fermented products as “powerhouse foods,” foods that boost gut health and reduce inflammation. Some nutrition experts recommend fermented foods should be included in national dietary recommendations.

In April, Today’s Dietitian published an article “The Facts About Fermented Foods.” In it, Dr. Robert Hutkins, a researcher and professor of food science at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, shared his expert opinion on fermentation. Hutkins wrote what many in the field consider the most exhaustive textbook on fermentation, “Microbiology and Technology of Fermented Foods.” He explained how fermented foods have a long history in the human diet.

“Indeed, during much of human civilization, a major part of the human diet probably consisted of bread, yogurt, olives, sausages, wine, and other fermentation-derived foods,” Hutkins told Today’s Dietitian. “They can be considered perhaps as our first ‘processed foods.’”

Hutkins, who studies the bacteria in fermented foods, said researchers like himself “are a bit surprised fermented foods suddenly have become trendy.”

“Consumers are now more interested than ever in fermented foods, from ale to yogurt, and all the kimchi and miso in between,” he says. “This interest is presumably driven by all the small/local/craft/artisan manufacturing of fermented foods and beverages, but the health properties these foods are thought to deliver are also a major driving force.”Fermented foods first appeared in the survey of registered dietitian nutritionists (RDNs) in 2017, where it was the 4th most popular superfood.

The full superfoods list includes:

- Fermented foods, like yogurt and kefir

- Avocado

- Seeds

- Exotic fruit, like acai, golden berries

- Ancient grains

- Blueberries

- Nuts

- Non-dairy milk

- Beets

- Green tea

- Published in Food & Flavor, Health

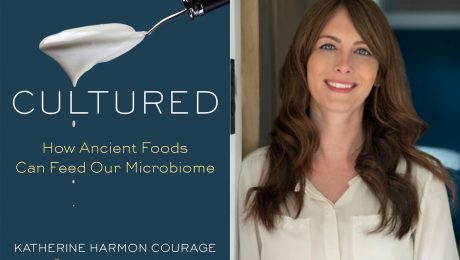

Q&A with Katherine Harmon Courage, Author of “Cultured: How Ancient Foods Can Feed Our Microbiome”

When Katherine Harmon Courage began investigating the microbiome 10 years ago as a writer for Scientific American, gut health was barely a blip on the public’s radar. It’s hard to believe today. You can’t walk by a grocery store shelf without reading dozens of labels advertising probiotic health benefits.

Today, gut health is at the forefront of the food industry. The probiotics supplement market is estimated to grow at a CAGR of 9.7 percent in the next seven years. And the market for probiotic-rich fermented foods is expected to grow at a CAGR of 4.98 percent in the next five years.

Gut health research from scientists and dieticians surged in the past decade. Courage was fascinated. “Looking at the food around the world and the connection between our ancient diet and microbes, that is really, really exciting,” she says. Courage spent a year travelling the world, exploring the traditional, gut-friendly cuisine of different cultures. She paired her culinary investigation with modern science into an engaging book: “Cultured: How Ancient Foods Can Feed Our Microbiome.”

Below, highlights from a Q&A with Courage on her new book, and her findings on the fermentation industry’s role in American’s evolving diets.

Q: You have been covering the microbiome since 2009. How has the scientific research progressed?

When I started covering it, there were small studies here and there, a lot from the Human Microbiome Project. Researchers were taking a census at the time, that we share our body with trillions of organisms. It was this niche area that I found super fascinating, but no one was talking about it much.

In the past decade, so much has changed. Science has evolved so much to learn about the connection between our health and our microbiome. We were raised to think germs are bad, bugs are bad, but we live with these commensal organisms.

Q: The food industry is taking notice of this research. What do you think of so many food products marketed with a gut health focus?

Talking to researchers, it’s interesting to see their perspective as scientists. They see the extreme of people thinking probiotics and microbes that are a marketing ploy to other people thinking probiotics and microbes will cure every health issue under the sun.

Microbiologists look at this critically. We’ve seen positive impacts on our health from it, but it won’t solve everything. We’re just at the beginning of understanding this relationship between these amazing and delicious fermented foods and our health.

Q: What’s the biggest misconception about microbes and our microbiome?

One of the misconceptions — and the one I had when I was thinking about this book — was the notion that if we eat something labeled probiotic, like a cup of yogurt, that we’re reinoculating our gut and restoring our gut health. Like if we eat a cup of yogurt, we’re good to go.

These microbes that we eat don’t stick around permanently. They’re just along for the ride. Weeks after we consume these, they’re not there anymore. When I learned this, I thought “There goes my research.” But when I looked into it more, in traditional culture and cuisines, people are eating fermented foods all the time, every day. It’s not about that one special food you eat or that one magic pill. It’s having those foods part of your daily cuisine and part of your life.

It’s great for fermentation producers. You don’t eat one jar of kimchi and call it good — you need to keep integrating it into your diet.

Q: Can a pill really fix our gut health?

Not being a scientist, I can’t say if it will or won’t fix our gut health. But talking to microbiologists who study this, it really is about exposing our bodies to these bacteria. We live our lives in such clean and pasteurized lives that we don’t get that microbial exposure. Their perspective is eating as many bugs, exposing ourselves to as many bugs, it will have a positive impact on our immune system as long as we’re healthy. A lot of the probiotic pills have been studied and they have positive health correlations, but we’re still learning so much about it.

Eating fermented foods, especially wild fermented foods, can be even more beneficial. Microbiologists and researchers in this field are really just starting to see what microbes are beneficial to our health. We can expose our bodies to more microbes through wild fermented foods because they’re so much more complex and have so many more microbes, rather than a yogurt with just three different microbes in it. We’re getting so much exposure through wild fermented foods.

Q: Why is it bad if we don’t properly feed our microbiome?

There’s the old friends hypothesis which is similar to the hygiene hypothesis. Our bodies have evolved to expect microbial exposure. But now our immune systems have gotten on this overactive trajectory, attacking these things they don’t need to.

We need to remember our native gut microbes, to feed them the nutrients they need to thrive. When we don’t feed our native microbes the fiber they need to thrive, they’ll eat the mucus lining in our gut, leading to more inflammation and asthma. We need to eat more microbes and feed the native microbes we do have.

Q: Can our native microbes change if we don’t feed them?

There’s been some interesting research out of Stanford’s Sonnenburg Lab. Mice fed on a diet with less fiber tend to have decreased microbiomes. Over generations, as the mice have pups, they pass that microbiome on to their pups. Generations later, these pups have super impoverished microbiomes. And they can’t come back and have a healthy microbiome by feeding them more fiber.

Q: Fermented foods are making waves in the food industry as the next big superfood. Tell me about fermented food in the book?

For the book, I got tor travel all over and explore these different cultures that have different fermented food traditions. I picked four main food places with quintessential fermented food — Greece to research yogurt, Korea to research kimchi, Japan to research miso and Switzerland to research cheese.

One of the cool discoveries I made travelling to these places was I discovered other aspects of the local diet that nourish the microbiome, other fermented foods and whole foods. These countries have different ways of thinking about eating than we do in America.

Q: What was the most eye-opening aspect of exploring other culture’s cuisine?

There were a couple. One, touring one of the big food markets in Seoul, Korea. Kimchi is their national food, but I was shown all these different fermented foods, different sauces, fermented soybean paste similar to miso, fermented veggies. It permeates their culture. Looking from far away in American grocery stores and farmers markets, you wouldn’t see it.

Second, in Japan, speaking with another author, we were talking about nato. Some people find nato challenging because it’s made with basic fermentation rather than acidic fermentation. The Japanese approach to fermented food, they teach at a very young age that “This is a wonderful, healthy food.” In America, we teach food as “Try this because it’s gratifying and yummy.” There’s this dichotomy of healthy foods versus gratifying goods. In Japan, there’s more of an understanding that there’s a wide variety of foods and you’re expected to eat all of them because that’s how you have a healthy life.

Q: Do you think this surge of fermented foods is a trend will disappear or a new food movement here to stay?

It’s here to stay. I expect to see it expanding and incorporating into more people’s lives. There is really compelling research with the health benefits, but there’s also these amazing flavors for those of us who weren’t raised with it. Like kimchi. Once you eat kimchi, food seems bland and lacking without it. Koreans describe it as “You need kimchi with every meal.” They can’t imagine eating it without. The flavor and texture experience is a big part of eating. We shouldn’t be forcing it down for our health, but truly enjoying it.

Q: Ancient foods are making an appearance in our diet again. Tell me what you found most fascinating in your research for this book on ancient foods.

One of the interesting things was how they are being incorporated into contemporary culture and cuisine. I went to a fermentation based restaurant in Tokyo, and I talked to the chef about how he’s integrating more traditional practices into contemporary cuisine and making very elegant meals out of them.

Q: Tell me more about your travels to Greece to learn about traditional yogurt. Modern yogurt is often criticized for the scientifically added probiotics. What did you find about traditional yogurt?

My image of yogurt was this fermented product with a few strains. But I wondered, with fermented yogurt products, are they just dumping strains in after they produced it?

Touring a family-owned, small-scale yogurt making facility in Greece, it was interesting seeing their process. They use backslopping, which is using part of the previous batch to inoculate the next batch. Traditionally, that was the way all of these products were made. It makes a richer microbial environment. We don’t know what strains are in it unless it’s sent off to a lab. Their strains come from the batch before and the batch before. Their yogurt would have strains unique to that product since they’ve made it for decades in that same place.

Q: Can better gut health help Americans notoriously destructive eating habits?

I think one of the keys is getting more fiber, especially prebiotic fiber from whole foods, not just a supplement, to really nourish a diverse gut microbiome. And, of course, eating more fermented foods.

For more information on Katherine Harmon Courage, visit her webpage. To purchase “Cultured,” visit Amazon.

- Published in Food & Flavor, Health, Science

Are More People Leaving Stressful Jobs for Simpler Life as Food Producer? Story of Oshikida Brand Miso’s New Owners

Are more people leaving stressful, fast-paced careers to start a simpler, rewarding life as a food producer? Articles are popping up all over the world about people ditching the corporate rat race and transitioning to traditional food making. An article from Japan Times details the story of a couple who left tech jobs in Tokyo to make miso in the country. Yu Maeda and Michinori are now taking over a 34-year-old Oshikida brand miso, an additive-free miso producer. Their miso is made by mixing cooked soybeans with kōji fermentation starter, salt and water.

Read more (Japan Times)

- Published in Business

The Art of Making Traditional Miso

Today most miso is industrially produced, but one of the most popular miso vendors in Los Angeles still uses traditional Japanese techniques to ferment miso paste, “recapturing the individuality of miso” according to the Los Angeles Times. Ai Fujimoto, who owns Omiso restaurant in the Hollywood Farmers Market, has fermented over 350 pounds of handmade soybean paste this year. The paste ferments for a few months for a light miso and ferments for over a year for dark miso. Each batch is different, “That’s what I love about it” Fujimoto says. She rents space at a commercial, shared-use kitchen to make her soybean paste. She enjoys experimenting with new recipes, even using recipes from YouTube videos.

Read more (LA Times) https://goo.gl/72muVk

- Published in Food & Flavor

- 1

- 2