Could Primeval Sake Variety Revive the Drink?

As Japanese consumers continue to swap beer, wine and cocktails over sake, the country’s national drink, industry experts think the doburoku sake variety could revive the dwindling sake market.

Doburoku is the catch-all term for sake that is unfiltered and gently carbonated. Described as rustic, cloudy and soupy, the drink’s brewing process doesn’t follow traditional sake rules. Brewers experiment with flavors, making it sweet or savory. It’s a “hyperlocal expression of soil and culture is its trademark,” reads an article on digital beverage publication Punch. Doburoku is typically unpasteurized, brewed in small batches.

There are only around 200 doburoku brewers in Japan, many who are farmers running small inns and restaurants. Only about two dozen of Japan’s 1,500 sake brewers make doburoku.

“At Heiwa Doburoku Kabutocho Brewery, the drink comes plain or aged, but also with unusual variations: dry-hopped, infused with matcha, mashed with persimmons, or blended with azuki beans, in part to tone down the alcoholic sharpness that many among sake’s detractors find off-putting,” continues the article. After fermenting the rice, koji and yeast for about two weeks, most of Heiwa’s doburoku is made in 7-liter pots in a backroom of the bar.

Norimasa Yamamoto, Heiwa Shuzou’s fourth-generation president, hopes to generate interest in sake by putting a “modern spin on the old-fashionred drink. …I’m hoping that, once you’ve tried doburoku, you’ll become curious enough about our rice fermentation tradition to delve into sake,” he says.

Read more (Punch)

- Published in Business, Food & Flavor

Fermentation Tops Restaurant Trend List

“Pickling and fermenting preparations are having a moment,” reads the 2023 Foodservice Industry Trend Report from Technomic. The food trend forecaster’s annual list rates fermentation “The Power of Preserving” as one of their top seven industry trends.

“Not only do these preparations promote ingredient preservation and health connotations but they also allow for unique culinary experimentation,” the report reads.

Technomic anticipates fermented food crafts at the bar, like kombucha, miso and sake. But lacto-fermentation, they predict, will also make its way to the menu, as restaurants detail their preserving processes “to provide consumers with a level of scientific transparency.”

Read more (Technomic)

- Published in Food & Flavor

Is the Future of Sake Canned?

Despite dedicated U.S. sake programs and educated American sommeliers, sake has been a harder sell in U.S. Federal regulations have never been able to properly define the drink. It’s taxed as a beer, but regulated as a wine. Education is a big issue. Many Americans think sake is a wine, causing them to drink too much of it and feel sick. Sake is brewed from fermented rice, making it similar to a beer.

“There’s a learning curve, but there’s also a bit of a cultural barrier. Sake can come across the way wine can — this very sophisticated product that’s expensive and that’s a bit esoteric, like you can’t really appreciate it unless you know all the nomenclature,” says Weston Konishi, president of the Sake Brewers Association of North America. “And then there’s the fact that Japanese sake tends to be labeled in Japanese, which most Americans can’t read. That’s been something of a barrier.”

Now more sake brewers are putting their sake in cans, making easy-to-purchase, grab-and-go options. It’s cheaper, too, at $5 a can versus $30 for a bottle.

“There’s something less intimidating about a can versus a bottle — that’s one advantage to canning sake. It’s not so erudite and out of reach,” says Konishi.

Inside Hook highlights six brands selling sake in cans.

Read more (Inside Hook)

- Published in Business

Domesticating Fermented Food Microbes

Humans have domesticated plants and animals since the early days of civilization, changing the life cycles, appearances and behaviors of crops and livestock. A new study shows humans have done the same to fermented products, selectively taming microbes. But as a result, microbial strains have evolved to where they can no longer survive in the wild.

“The burst of flavor from summer’s first sweet corn and the proud stance of a show dog both testify to the power of domestication,” reads an article in Science titled “Humans tamed the microbes behind cheese, soy, and more.” “But so does the microbial alchemy that turns milk into cheese, grain into bread, and soy into miso. Like the ancestors of the corn and the dog, the fungi and bacteria that drive these transformations were modified for human use. And their genomes have acquired many of the classic signatures of domestication.”

Humans have used selective breeding to produce the most desired traits in plants and animals – for example, making a plant less bitter or an animal larger. Thousands of years of domestication have changed DNA. Though microbes can’t be bred the same way, “humans can grow microbes and select variants that best serve our purposes.” It’s now left “genetic hallmarks similar to those in domesticated plants and animals: The microbes have lost genes, evolved into new species or strains and become unable to thrive in the wild.”

Scientists shared this research during two talks at Microbe 2022, the annual meeting of the American Society for Microbiology in Washington D.C. The talks – “Origins and Consequences of Microbial Strain Diversity” and “Microbial Diversity in Food Systems: From Farm to Fork”

– were convened by TFA Advisory Board members Benjamin Wolfe, PhD, ofTufts University, and Josephine Wee, PhD, from Penn State. They invited various academics to present their research on these topics.

Microbial Domestication in Cheese

Wolfe said the studies “are getting to the mechanisms” of how microbial domestication works. They reveal “which genes are key to microbes’ prized traits – and which can be lost,” continues the Science article. This work is critical to the future of food, as these microbe gene traits can shape fermented foods and beverages.

Presenters included Vincent Somerville, PhD, from the University of Lausanne, Switzerland, speaking on the changing genomic structure of cheese cultures. He pointed out that bread yeasts have long been domesticated. They’ve lost so much of their genetic variation that they can’t live in the wild. Other microbes are “lacking clear evidence of domestication … in part because [their] microbial communities can be hard to study,” he said.

Somerville’s research revolves around a starter culture for a Swiss hard cheese. Bacterial cheese starters were created by early cheesemakers; in the 70s, samples of these cultures began being banked to ensure quality. But Somerville and his collaborators, after sequencing the genomes of more than 100 of these samples, found little genetic diversity, with just a few strains of two dominant species..

“The exciting thing from this work was having samples over time,” Wolfe said. “You can see the shaping of diversity,” with changes in the past 50 years hinting at the trajectory of change over past centuries.

Domesticated vs. Wild Aspergillus

John Gibbons, a genomicist at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, presented on Aspergillus oryzae, “the fungus that jump-starts production of sake from rice, and soy sauce and miso from soybeans.” Farmers cultivate A. oryzae, which reproduces on its own. “But when humans take a little finished sake and transfer it to a rice mash to begin fermentation anew, they also transfer cells of the fungal strains that evolved and survived best during the first round of fermentation,” the article reads.

Gibbons compared the genomes of A. oryzae strains with those of A. flavus, it’s wild ancestor. Human involvement in transferring the fungus has “boosted A. oryzae’s ability to break down starches and to tolerate the alcohol produced by fermentation.” The domesticated Aspergillus strains may have up to five times the number of genes used to break down starches compared to their ancestors.

“The restructuring of metabolism appears to be a hallmark of domestication in fungi,” he said.

Gibbons also found the genes of domesticated A. oryzae to have little variation. And some key genes have disappeared, “including those for toxins that would kill the yeast needed to complete fermentation — and which can make humans sick.” The article concludes: “Domestication has apparently made A. oryzae more human friendly, just as it bred bitter flavors out of many food plants.”

- Published in Science

The Unsung History of Umami

In the early 1900s, Japanese chemist Dr. Kikunae Ikeda discovered the flavor umami by distilling it from soup stock. That compound – which is an amino acid, glutamate — produces the savory flavor in meat, mushrooms and seaweed. Ikeda called the flavor after the Japanese word umami which means “essence of deliciousness.”

“It is the peculiar taste which we feel as umai, meaning brothy, meaty or savory, arising from fish, meat and so forth,” Ikeda wrote in the Journal of Tokyo Chemical Society.

A huge discovery, umami became the fifth flavor next to salty, sweet, sour and bitter. Ikeda went on to start a company, Ajinomoto, which mass produces monosodium glutamate — MSG — a key ingredient in producing umami.

But it took nearly 100 years for umami to be recognized by the broader scientific community, especially in the western world. An NPR story points to the anti-Asian “Chinese Restaurant Syndrome” which began in the 60s and 70s. MSG was vilified as an unhealthy additive, numbing mouths and making people sick (an apparent fable modern food scientists have never been able to prove). Another reason: umami research may have been ignored in the U.S. because of tension with Japan during World War II .

“Fermented foods and seasonings like sake, soy sauce, miso were a large part of the diet in Japan and also a large part of the economy. And so research into the flavor components of those kinds of foods were an important part of rationalizing diet in Japan.”

says Victoria Lee, professor and author of “The Arts Of The Microbial World.”

Read more (NPR)

- Published in Food & Flavor

Reviving Sake with SoCal Style

James Jin of Nova Brewing Co. doesn’t want to create a Japanese-style sake — he’s working to create a Southern Californian sake.

Jin uses Calrose rice grown near Sacramento, imports koji and yeast from Japan and designs his own brewing equipment. The flavor of his modern sake is thanks to a secret blend he uses to make the koji rice (the base for the sake), utilizing both yellow and black koji spores, as well as yeast from the Brewing Society of Japan. The flavor — more wine-like, fruitier, higher in acidity and easily paired with food — “it’s a lot more appealing to the younger generation.”

“I respect the history of sake brewing, but it’s a dying art in Japan,” Jin says, adding, “Sales of sake [are] constantly going down [there]. I’m one of the few brewers in America trying to bring the dying art back to life.”

“I’m not a Japanese brewer. I’m an American brewer. I purposefully do things they wouldn’t do in Japan.”

Nova Brewing produces four sakes and 10 craft beers at their facility in Covina, California. They are the only craft sake brewery and tasting room in Los Angeles County — and the only sake and beer hybrid producer in California.

Read more (Los Angeles Times)

- Published in Business, Food & Flavor

Japan’s Rich Culture of hakkо̄

“If there were a country whose cuisine excels in the realm of fermented foods, it’s Japan,” highlights an article in Discover Magazine. In Japan, hakkо̄ (which translates to “fermentation”) forms “the very basis of gastronomy in the island nation,” continues the article.

Tsukemono (pickles), miso (fermented soy bean paste), soy sauce, nattо̄ (fermented soy beans), katsuobushi (dried fermented bonito flakes), nukazuke (vegetables pickled in rice bran), sake and shōchū (liquor distilled from rice, brown sugar, buckwheat or barley) are all staples of traditional Japanese meals.

Nattо̄ in particular has been proven to lower obesity rates, boost levels of dietary fiber, protein, calcium, iron and potassium and reduce diastolic blood pressure.

Though the article highlights the few, limited studies on the effects of other fermented foods, it also noted how difficult it is to study them. There little money behind the study of traditional foods (outside of yogurt), and participants in any such research would need to be on the same diets and exercise programs in order to produce objective results. A study would also need to take place over multiple years — “the cost would be vast, the ethics questionable.”

Read more (Discover Magazine)

- Published in Food & Flavor

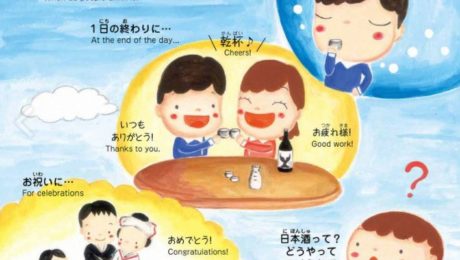

Picturing Traditional Sake

Hoping to spur interest in traditional sake, a Japanese producer has published a picture book What is Sake? that takes readers on a tour of their sake facility. Suigei Brewing Co., based in the western city of Kochi, uses the book to detail how sake is made. The bilingual book includes English translations.

The president of Suigei Brewing Co., Hirokuni Okura, notes Japan’s sake culture is gradually being forgotten. He said he desires to “have both adults and children view sake, an element of Japanese food culture, as something close to them.”

The book’s illustrator, Misae Nagai, featured all 53 employees of Suigei in her charming illustrations.

Read more (The Mainichi)

- Published in Business, Food & Flavor

Sake Brewers Suffer in Japan

As Covid-19 restrictions are lifted, American sake breweries are opening their doors to customers again. But across the world in Japan, where sake originated, many izakaya or sake pubs remain closed. Japanese brewers expect sales to slump for a second year in a row because of the pandemic.

“This right now might be the most challenging time for the industry,” says Yuichiro Tanaka, president of Rihaku Sake Brewing. “There’s nothing much we can do about that. In our company, we’re trying to become more efficient and streamline our processes so that once the world economy returns to what it formerly was, we’ll be able to much more efficiently fill orders.”

Tanaka, Miho Imada (president and head brewer of Imada Sake Brewing) and Brian Polen (co-founder and president of Brooklyn Kura) spoke in an online panel discussion Brewers Share Their Insider Stories, part of the Japan Society’s annual sake event. John Gauntner, a sake expert and educator, moderated the discussion and translated for Tanaka and Imada, who both gave their remarks in Japanese. (Pictured from left to right: Gautner, Tanaka, Imada and Polen.)

Recovery Struggles

Japan — which has been slow to vaccinate (only 9% of the population has been fully vaccinated, compared to 47% in the United States) — is currently in a third state of emergency. In the country’s large cities, no alcohol can be served in restaurants. “This is just devastating to the industry,” says Gaunter.

Though sake pubs in smaller metropolitan areas and countryside regions are allowed to be open, few people are out drinking. Many pubs have closed, and others refuse entry to anyone from outside of their prefecture.

“Sales of sake are very seriously affected,” says Imada, one of few female tôji or master brewers. “Rice farmers that grow sake rice are seriously affected as well. If brewers can’t sell sake, they have no empty tanks in which to make sake, so they don’t order any rice and the effects are transmitted down to rice farmers.”

Sake rice is more challenging to grow than table rice because the rice grains must be longer. The amount of sake rice planted in Hiroshima — where Imada Sake Brewing is based — is down 30-40%. Farmers may give up growing sake rice and switch to table rice for good.

The effects of Covid-19 on Japan’s sake brewers will linger into the fall when the next brewing season starts again.

“We cannot really expect a recovery in the amount of sake produced next season, and so therefore production will drop for two years in a row,” she says.

Premium sake brewers with rich generational historys — like Imada Sake Brewing and Rihaku Sake Brewing — are struggling to sell their high-end products.. Department store in-store tastings — a boon to premium sake brewers — have disappeared.

Adapting to Covid

In New York, as pandemic recovery efforts continue, Polen has seen the pent-up demand from consumers. Brooklyn Kura’s retail, on-premise and taproom sales are increasing. After scaling back production and their team in 2020, Brooklyn Kura is now hiring again.

“More importantly, and I think the silver lining out of this, we really needed to redouble our efforts to create a direct line of communication with our best customers,” Polen says.

During the pandemic, Brooklyn Kura launched both a direct-to-consumer business and a subscription service featuring limited-run sakes. “That’s helped us on our road to recovery.”

Imada Sake, too, found ways to improve business. They’re selling bottles and hosting tasting events through their website.

“One of the principles of the Hiroshima Tôji Guild [guild of master sake brewers], the expression is ‘Try 100 things and try them 1,000 times.’ Or in other words the point is keep trying new things and see what contributes towards improvement,” Imada says. “These words convey the spirit of using skill and technique or technology to get beyond difficulties.”

Imada Sake exports 20% of its production; as more countries recover, exports continue to grow. Direct-to-consumer sales, she says, vary and are only constant around Christmas.

Rihaku Sake sells much of their sake to distributors and is seeing international exports increase. They also began direct-to-consumer internet sales, but that channel “didn’t grow as much as I was hoping.”

Consumer Education

France and Italy export billions of dollars of wine a year. Polen argues that sake could be an equally profitable export for Japan. Education and exposure, he says, are the challenge.

“In craft beer and fine wine, a lot of those initial encounters with those products come in places like the tap room in Brooklyn or the wineries in California or the local craft brewery, so creating more of those connection points and initial introduction points in a market like the U.S., having a better facility to distribute sake across the U.S., will help to expand the market, not just to domestic producers but also for the storied producers of Japan as well,” Polen says.

Sake is the national beverage of Japan, and strict brewing laws strive to keep it pure. Japanese sake can only be made with koji and steamed rice. Add hops to it and the drink cannot be called sake legally anymore.

Many sake tôji in Japan are running a multi-generational family brewery.“These craftsmen, who have been brewing sake since they were young, have decades of experience to develop what we call keiken to chokkan or experience and intuition,” Tanaka says, adding that Japan is the only place to buy certain industrial-sized sake making machines such as steamers and pressers. “There’s a lot of advantages that breweries in Japan have. If brewers overseas get too good, this might actually cause problems for brewers in Japan. However, more important than that, I think it’s important for all of us to continue to study how to make better and better sake so everyone around the world can enjoy it.”

Rihaku tries to make their sake recognizable to local consumers who are unfamiliar with the rice wine. Their Junmai Ginjo sake has the nickname “Wandering Poet,” a reference to the famous poet Li Po. Legend says Li Po drank a bottle of sake then wrote 1,000 poems.

“We think a lot about how to get more people that are non-Japanese and outside of the Japanese context excited about sake making and excited about the sake we make,” Polen says. “That includes those folks that are passionate fermenters, like the beer community, that really want to know and learn about things like spontaneous fermentation. So (sake) styles, like yamahai and kimoto, are very easy transition points, very easy talking points for us with that community of brewers and consumers that are really excited to drill deeper into fermentation, especially natural fermentation.”

- Published in Business

Pairing Sake with Food

Does sake go well with Western dishes? Josh Dorcak, chef of Japanese restaurant Mäs, tells Forbes why he thinks sake is an excellent pairing with all food types, maybe even more so than wine.

“Sake pairs with everything,” Dorcak says. “With wine often it seems like there are these rules that one must follow while sake often fits the bill for creative pairings.”

Read more (Forbes)

- Published in Food & Flavor

- 1

- 2