Redzepi: We Need Restaurants to “Feel Alive”

Restaurants have been under tremendous economic pressure, suffering from business losses during the Covid-19 pandemic. And there’s now a staffing shortage, as long hours and low pay have driven many away from the industry.

Bloomberg columnist Bobby Ghosh explored how restaurant dining may change in an Instagram live interview with Rene Redzepi, owner and co-owner of Noma, Copenhagen’s two-Michelin star restaurant world-renowned for its experimental fermentation lab. Pandemic restrictions shut down Noma twice, forcing Redzepi to create additional revenue streams outside the traditional dining room.

In the summer of 2020, Noma opened an outdoor, walk-in burger and wine bar. Earlier this month, they announced Noma Projects, a direct-to-consumer line that will initially sell garums.

Below are highlights from Ghosh’s interview with Redzepi.

Ghosh: What did you learn about how people were feeling about returning to restaurants?

Redzepi: Restaurants, you don’t need them to stay alive but you need them to feel alive. That was very, very clear, that people were ready to go out. You know they say it’s the catch-up effect, and that definitely happened here in Copenhagen. People were everywhere, they were in piles to get a bite to sit down, have a glass of wine and meet other people.

Ghosh: When you began to think about reopening the proper dining space and planning your menu for the reopening, did you have any particular thoughts or concerns about whether people’s habits in restaurant dining might have changed in the course of the year that they were all locked up?

Redzepi: Yeah, so we went through the first lockdown, opened up, we were open for about five months and then it all came back and we had to close (again during the second lockdown). On the second lockdown, we were shut for six months and, in that time, we were very worried about everything, I mean we still are, but I guess we’re a little less worried now than before because we’re finally open again. We did think “Would people even sit for hours in a restaurant? What is it that everyone wants?” Besides that, people in Denmark, they started really cooking at home again. Takeaway offerings had become quite common, even from some of the best restaurants, something that would be considered completely impossible five years ago. If you had takeaway as a fine dining establishment, you sort of sold out in a way and that was starting to happen.

But I decided with myself, and that was a personal decision, is that in my life I need this creativity, I need to have guests, I need to work on a menu on a daily basis, so during the lockdown I went to work every day in the kitchen as if we were going to open the following day. We actually made two full menus and one of them will never be served because we ended up being closed throughout it. And then we said “OK, let’s just open up and see what happens, will people still want to come out?” and we opened up our reservations knowing that we would cater only to 100% local crowd and it’s gone really well, really really well.

Ghosh: The thrill of being in a nice restaurant and being able to talk to people and enjoy a meal is incomparable um and I do appreciate the value of fun after the year and a half that we’ve all had. Can you give us an example of a dish that you have in your menu now that reflects this attitude of fun, the surprise.

Redzepi: Swedish saffron believe it or not, it’s really, really strong and tastes amazing. We make this fudge with it and we found out that you can actually use the sort of the cutting of walnut as a wig for candles because the oil content in the walnut makes it flammable. And so we basically shaped or molded this little toffee into a candle. It sounds complicated but it’s quite easy to do when it’s hot and then we put this walnut light into it and it comes to the table when they’re drinking coffee and people think it’s you know for coziness and then as it burns out people are then instructed to eat it that’s a that’s a moment where that’s fun you know it’s creativity, it’s delicious it surprises people and it just really makes it makes a difference to people you can feel that they’ve been needing something like that.

Ghosh: What have you learned that you didn’t already know about restaurant economics over the past year that now factors in your thinking about what Noma is and what Noma needs to be in the future.

Redzepi: Oh man, you’re hitting something that we’ve been talking about for the past two years because, particularly in the last year-and-a-half, restaurant economics, they’re terrible. We’ve had 18 years of operation and we’ve had an average profit of 3%. It’s just enough to keep us running and keep painting the house, so during this pandemic we did think to ourselves “Are we going to continue like this for another 18 years, where we don’t have any money to change anything, even if we want it?” You know we’re going to have to find different ways of operating so that we can have a different economics in it. We have to figure out a way if we want to be here for another 18 years because you know it won’t continue like this. So we have definitely thought of many many things and recently we launched this thing that we call Noma Projects. Noma Projects is a sort of a platform to launch a myriad of things, it’s a for-profit company, but we only want to attack projects that also connect to some sort of a worldly issue, and the first project one is is a vegan and a vegetarian garum sauce that you use as a flavoring to add umami to your vegetarian and vegan cooking. It’s a way to help people eat more vegetarian so that’s project one, that’s something that we worked on almost almost since the first lockdown that happened to us we were like we need to step into this.

Ghosh: About six months ago, I did a piece about restaurant economics and the pandemic. I talked to your friend David Chang of Momofuku. We’re saying that we have to figure out more ways to find revenues outside of the dining room. You know, can we get 50% of the revenue from outside of the dining room where the margins are larger to sustain, to underwrite the amazing creativity that goes on in your kitchens? Is that possible? Have consumer tastes or consumer behaviors now changed in a way that will allow that kind of thing?

Redzepi: I think what happened during the pandemic is that it’s been considered more OK for restaurants of say Momofuku caliber or Noma to actually think of ways to put better economics into the system. That has opened a new door and for us, we’re grabbing that opportunity, we need to, definitely. Our industry needs to, in general. It’s an industry that’s under copious amounts of pressure, we deal with poor profit margins, low incomes, people are overworked, they’re underpaid, there’s bad management and a lot of it is a result of there’s simply no money in the industry, people can’t afford to do maneuver any new way they want, and we don’t have any business training either. It’s very interesting what’s going on. I think a lot of creativity is going to come out of restaurants in the next couple of years.

Ghosh: Now in addition to being a chef, you’re a thinker in your line of work. Through MAD Academy, which used to be anyway your annual gathering of of great chefs from around the world, you’ve spent a lot of time thinking about your industry and the future of your industry. I imagine that during the course of the past year, year-and-a-half you’ve had many conversations with the kinds of people who would previously have come to that conference. What are some of the common themes, the common challenges for fine dining establishments?

Redzepi: I think in food in general, the most common problem, and I think it’s going to continue for a while, is that there’s a gigantic staff shortage right now. I think in the pandemic, a lot of people have had an opportunity to rethink their life and say “OK, am I in this industry for the next 20 years or is this a moment for me now to start studying or become a farmer or something else.” That is really the biggest issue that we have right now, there’s no question in my mind. This is something that at MAD we’ve been discussing for almost a decade. If we’re not able to help transform (and this includes myself by the way I’ve spoken about this many times) this gigantic lack of leadership that we face as an industry where we have a poor ability to actually just manage ourselves, manage our restaurants and be supportive of people, that will be the first step that needs to happen which is slowly happening. But then providing better pay and better work hours, that are related to economics. I see our industry being far from that, unless we figure out a way to either charge more that there’s more value towards foods and people that work in the industry or we find other revenue streams. Those are the big, big questions that we are dealing with at MAD. At Noma, I deal with this as a employer myself, how to actually be an inspiration, but how to also provide for staff that are having children, and how can we have everyone stay here for 40 years in this industry? That’s really hard questions.

- Published in Business

Which Are Healthier — Fermented or Acidified Pickles?

Researchers with the USDA have found that fermented cucumber pickles contain more of the naturally-occurring gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) than do their acidified counterparts. Results of this study of commercially-available pickles were recently published in the Journal of Food Composition and Analysis.

GABA works as a neurotransmitter in the brain. It has been scientifically proven that GABA, when consumed in foods or supplements, reduces blood pressure, improves decision making, reduces anxiety and boosts immunity.

Fermented cucumber pickles undergo a lactic acid fermentation, whereas acidified cucumber pickles are submerged in an acidic brine. The fermented pickles with the most GABA were made in a low-salt fermentation, and the products were prepared for direct consumption. GABA content also was found to remain stable during storage for fermented cucumbers.

“Worldwide, people are interested in consuming fermented foods as part of a healthy lifestyle. Most often, we associate the healthfulness of fermented foods with probiotic microbes. But many fermented foods contain few to no microbes when consumed,” said Jennifer Fideler Moore, North Carolina State University graduate research assistant and one of the study co-authors, in a USDA-ARS press release. “Our research shows that the health-promoting potential of lactic acid fermented cucumbers reaches far beyond the world of probiotics. This opens the door to more research into health-promoting compounds made during fermentation of fruits and vegetables.”

Adds Suzanne Johanningsmeier, study co-author and USDA Agricultural Research Service (USDA-ARS) Research Food Technologist: “Fruits and vegetables are made up of thousands of unique molecules. These molecules rule the flavor, texture, and nutritional value, but it is difficult to study them in such complex systems. To tackle this problem, we use advanced analytical chemistry techniques like mass spectrometry to study food molecules and figure out the best food processing methods for improved quality of fruit and vegetable products.”

[Johanningsmeier presented further details of the study during a TFA webinar.]Noma Goes DTC

Noma is coming into the home kitchen.

The fermentation-focused restaurant, lauded as one of the top restaurants in the world, is selling its first line of packaged products. Two garums — vegan Smoked Mushroom and vegetarian Sweet Rice and Egg — will soon be available to ship internationally through the brand’s website, Noma Projects.

“It’s a space for us to channel our knowledge, our craft and experimentation into a new endeavor,” says René Redzepi, chef and co-owner of the Copenhagen-based restaurant.

Redzepi shared details of the launch in a video on the site. Noma Projects will include pantry products and community-based initiatives, “a way for us to address issues we care about through the lens of food.”

Noma’s Pantry Staples

The garums are Noma’s “take on a 1,000-year-old recipe that we’ve been developing over the past two decades.” Redzepi says the “potent, umami-based sauces” have been the “key to our success at Noma in our vegetarian and vegan menus.

He hopes the garums will help more people cook plant-based meals, announcing in the video: “We want to help you bring more vegetables into your everyday cooking.” The garums provide the flavor of meat and fish without the animal. The website description notes: “Shifting towards a more plant-based diet is the easiest way for an individual to help the environment. We hope these garums will do the same for you that they’ve done for us, help inspire and create more delicious plant-based meals when you cook at home.”

These products were developed in Noma’s Fermentation Lab, where dozens of pantry staples were tested before landing on the garums. A garum is the “concentrated essence of its main ingredient” with a strong umami flavor, and Redzepi describes it to the WSJ. Magazine (the luxury magazine published by Wall Street Journal): “It has the potency of a soy sauce, except it tastes of what it is.” Both are brewed with koji rice, what Redzepi calls the “mother fungus.”

The garums are currently fermenting and will be ready for shipping in the fall or winter. The expected price point is $20-$35 for a bottle.

And more garums are in the works. Noma Fermentation Lab director, Jason Ignacio White, says a roasted chicken wing garum is next.

“It tastes like super chicken stock with umami,” White tells WSJ. Magazine, ”so it’s a familiar flavor, but there’s something about it that you can’t really put your finger on, that makes your tongue dance.”

Improving Profitability

Despite Noma’s expensive tabs — the 20-course tasting menu costs 2,800 Danish kroner (or around $447), and the wine pairing is another 1,800 Danish kroner (or around $287) — in the 18 years since it opened, the restaurant has hovered at only a 3% profit margin. Redzepi hopes Noma Projects will make more money. While it is “a family-run garage project,” its goal is to reach a million customers.

Like many restaurants around the world, Noma shut down during the pandemic. They reopened as a burger and wine bar in June 2020, and the walk-up, outdoor dining experience was such a success that it became a permanent restaurant, POPL.

Noma resumed regular operations on June 1, 2021. The pandemic closure allowed Redzepi and his team to finally tackle the retail brand, something he said they had debated for years.

- Published in Business, Food & Flavor

Fermentation for Alternative Proteins

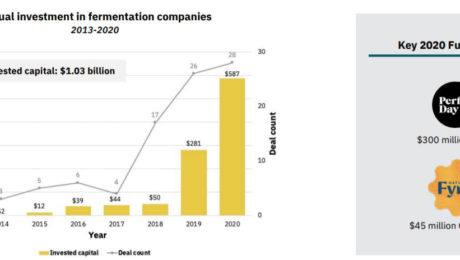

Investments in alternative protein hit their highest level in 2020: $3.1 billion, double the amount invested from 2010-2019. Over $1 billion of that was in fermentation-powered protein alternatives.

It’s a time of huge growth for the industry — the alternative protein market is projected to reach $290 billion by 2035 — but it represents only a tiny segment of the larger meat and dairy industries.

Approximately 350 million metric tons of meat are produced globally every year. For reference, that’s about 1 million Volkswagen Beetles of meat a day. Meat consumption is expected to increase to 500 million metric tons by 2050 — but alternative proteins are expected to account for just 1 million.

“The world has a very large demand for meat and that meat demand is expected to go up,” says Zak Weston, foodservice and supply chain manager for the Good Food Institute (GFI). Weston shared details on fermented alternative proteins during the GFI presentation The State of the Industry: Fermentation for Alternative Proteins. “We think the solution lies in creating alternatives that are competitive with animal-based meat and dairy.”

Why is Alternative Protein Growing?

Animal meat is environmentally inefficient. It requires significant resources, from the amount of agricultural land needed to raise animals, to the fertilizers, pesticides and hormones used for feed, to the carbon emissions from the animals.

Globally, 83% of agricultural land is used to produce animal-based meat, dairy or eggs. Two-thirds of the global supply of protein comes from traditional animal protein.

The caloric conversion ratios — the calories it takes to grow an animal versus the calories that the animal provides when consumed — is extremely unbalanced. It takes 8 calories in to get 1 calorie out of a chicken, 11 calories to get 1 calorie out of a pig and 34 calories to get 1 calorie out of a cow. Alternative protein sources, on the other hand, have an average of a 1:1 calorie conversion. It takes years to grow animals but only hours to grow microbes.

“This is the underlying weakness in the animal protein system that leads to a lot of the negative externalities that we focus on and really need to be solved as part of our protein system,” Weston says. “We have to ameliorate these effects, we have to find ways to mitigate these risks and avoid some of these negative externalities associated with the way in which we currently produce industrialized animal proteins.”

What are Fermented Alternative Proteins?

Alternative proteins are either plant-based and fermented using microbes or cultivated directly from animal cells. Fermented proteins are made using one of three production types: traditional fermentation, biomass fermentation or precision fermentation.

“Fermentation is something familiar to most of us, it’s been used for thousands and thousands of years across a wide variety of cultures for a wide variety of foods,” Weston says, citing foods like cheese, bread, beer, wine and kimchi. “That indeed is one of the benefits for this technology, it’s relatively familiar and well known to a lot of different consumers globally.”

- Traditional fermentation refers to the ancient practice of using microbes in food. To make protein alternatives, this process uses “live microorganisms to modulate and process plant-derived ingredients.” Examples are fermenting soybeans for tempeh or Miyoko’s Creamery using lactic acid bacteria to make cheese.

- Biomass fermentation involves growing naturally occurring, protein-dense, fast-growing organisms. Microorganisms like algae or fungi are often used. For example, Nature’s Fynd and Quorn …mycelium-based steak.

- Precision fermentation uses microbial hosts as “cell factories” to produce specific ingredients. It is a type of biology that allows DNA sequences from a mammal to create alternative proteins. Examples are the heme protein in an Impossible Foods’ burger or the whey protein in Perfect Day’s vegan dairy products.

Despite fermentation’s roots in ancient food processing traditions, using it to create alternative proteins is a relatively new activity. About 80% of the new companies in the fermented alternative protein space have formed since 2015. New startups have focused on precision fermentation (45%) and biomass fermentation (41%). Traditional fermentation accounts for a smaller piece of the category (14%). There were more than 260 investors in the category in 2020 alone.

“It’s really coming onto the radar for a lot of folks in the food and beverage industry and within the alternative protein industry in a very big way, particularly over the past couple of years,” Weston says. “This is an area that the industry is paying attention too. They’re starting to modify working some of its products that have traditionally maybe been focused on dairy animal-based dairy substrates to work with plant protein substrates.”

Can Alternative Protein Help the Food System?

Fermentation has been so appealing, he adds, because “it’s a mature technology that’s been proven at different scales. It’s maybe different microbes or different processes, but there’s a proof of concept that gives us a reason to think that that there’s a lot of hope for this to be a viable technology that makes economic sense.”

GFI predicts more companies will experiment with a hybrid approach to fermented alternative proteins, using different production methods.

Though plant-based is still the more popular alternative protein source, plant-based meat has some barriers that fermentation resolves. Plant-based meat products can be dry, lacking the juiciness of meat; the flavor can be bean-like and leave an unpleasant aftertaste; and the texture can be off, either too compact or too mushy.

Fermented alternative proteins, though, have been more successful at mimicking a meat-like texture and imparting a robust flavor profile. Weston says taste, price, accessibility and convenience all drive consumer behavior — and fermented alternative proteins deliver in these regards.

And, compared to animal meat, alternative proteins are customizable and easily controlled from start to finish. Though the category is still in its early days, Weston sees improvements coming quickly in nutritional profiles, sensory attributes, shelf life, food safety and price points coming quickly.

“What excites us about the category is that we’ve seen a very strong consumer response, in spite of the fact that this is a very novel category for a lot of consumers,” Weston says. “We are fundamentally reassembling meat and dairy products from the ground up.”

- Published in Business, Food & Flavor, Health, Science

Measuring and Monitoring Fermented Food Microbiomes

Analyzing the microbiome of a fermented food will help manage product quality and identify the microbes that make up the microscopic life. Though diagnostic techniques are still developing, they’re getting cheaper and faster.

“Why should we measure the microbial composition of fermented foods? If you can make a great batch of kimchi or make awesome sourdough bread, who cares what microbes are there,” says Ben Wolfe, PhD, associate professor at Tufts University. “But when things go bad, which they do sometimes when you’re making a fermented food, having that microbial knowledge is essential so you can figure out if a microbe is the cause.”

Wolfe and Maria Marco, PhD, professor at University of California, Davis, presented on Measuring and Monitoring Fermented Food Microbiomes during a TFA webinar. Both are members of the TFA Advisory Board. During the joint presentation, the two gave an overview on microbiome analysis techniques, such as culture-dependent and culture-independent approaches.

Measuring Microbial Composition

Wolfe says there are three reasons to measure the microbial composition of fermented foods: baseline knowledge, quality control and labelling details.

“Just telling you what is in that microbial black box that’s in your fermented food that can maybe be really useful for thinking about how you could potentially manipulate that system in the future,” he says.

What can you measure in a fermented food? First there’s structure, which can determine the number of species, abundance of microbes and the different types. And second is function, which can suggest how the food will taste, gauge how quickly it will acidify and help identify known quality issues.

Studying these microorganisms — unseen by the naked eye — is done most successfully through plating in petri dishes. This technique was developed in the late 1800s

“This allowed us to study microorganisms at a single cell level to grow them in the laboratory and to really begin to understand them in depth,” Marco says. “This culture-based method, it remains the gold standard in microbiology today.”

However, there’s been a “plating bias since the development of the petri dish,” she says. Science has focused on only a select few microbes, “giving us a very narrow view of microbial life.” Fewer than 1% of all microbes on earth are known.

The microbes in fermented foods and pathogens have been studied extensively.“Over these 150 years we have now a much better understanding of the processes needed to make fermented foods, not just which microbes are these but what is their metabolism and how does that metabolism change the food to give the specific sensory safety health properties of the final product,” she says

Marco and Wolfe both shared applications of these testing techniques from research at their respective universities.

Application: Olives

At UC Davis, Marco and her colleagues studied fermented olives. Using culture-based methods, they found that the microbial populations in the olives change over time. When the fruits are first submerged for fermentation, there’s a low number of lactic acid bacteria on them — but within 15 days, these microbes bloom to 10-100 million cells per gram.

Marco was called back to the same olive plant in 2008 because of a massive spoilage event. The olives smelled and tasted the same, but had lost their firmness.

Using a culture-independent method to further study what microbes were on the defective olives, she discovered a different microbiota than on normal ones, with more bacteria and yeast.

The culprit was a yeast.“Fermented food spoilage caused by yeast is difficult to prevent,” Marco says. “New approaches are needed.”

Application: Sourdough

At Tufts, Wolfe was one of the leaders on a team of scientists from four different universities that studied 500 sourdough starters with an aim to determine microbial diversity. Starters from four continents were examined in the first sourdough study encompassing a large geographic region.

The research team identified a large diversity among the starters, attributed to acetic acid bacteria. They also found geography doesn’t influence sourdough flavor.

“Everyone talks about how San Francisco sourdough is the best, which it is really great, but in our study we found no evidence that that’s driven by some special community of microbes in San Francisco,” Wolfe said. “You can find the exact same sourdough biodiversity based on our microbiome sequencing in San Francisco that you can find here in Boston or you could find in France or in any part of the world, really.”

Wolfe and Marco will return for another TFA webinar on July 14, Managing Microbiomes to Control Quality.

- Published in Science

Supplements vs. Fermented Foods

Two UCLA professors of medicine encourage people “rather than thinking in terms of supplements, add some fermented foods to your diet.” In a Q&A, the doctors say the popularity of probiotics, postbiotics and the gut microbiome has blurred their value, despite the plethora of reputable scientific research. Product manufacturers — as has happened before, with terms like “gluten-free” — have begun labelling everything as containing -biotics or benefitting the gut microbiome.

“The word probiotics refers to the beneficial microbes found in certain fermented foods and beverages, as well [as] in specially formulated nutritional supplements,” write UCLA doctors Eve Glazier and Elizabeth Ko. “That means that any fermented food that contains or was made by live bacteria contains postbiotics. … Initial findings suggest that postbiotics may play a role in maintaining a balanced and robust immune system, support digestive health and help to manage the health of the gut microbiome.”

Read more (Journal Review)

- Published in Science

What’s the Actual Probiotic Count of Commercial Kefir?

A new peer-reviewed study from researchers at the University of Illinois and Ohio State University found 66% of commercial kefir products overstated probiotic count and “contained species not included on the label.”

Kefir, widely consumed in Europe and the Middle East, is growing in popularity in the U.S. Researchers examined the bacterial content of five kefir brands. Their results, published in the Journal of Dairy Science, challenge the “probiotic punch” the labels claim.

“Our study shows better quality control of kefir products is required to demonstrate and understand their potential health benefits,” says Kelly Swanson, professor in human nutrition in the Department of Animal Sciences and the Division of Nutritional Sciences at the University of Illinois. “It is important for consumers to know the accurate contents of the fermented foods they consume.”

Probiotics in fermented products are listed in colony-forming units (CFUs). The more probiotics, the greater the health benefit.

According to a news release from the University of Illinois: “Most companies guarantee minimum counts of at least a billion bacteria per gram, with many claiming up to 10 or 100 billion. Because food-fermenting microorganisms have a long history of use, are non-pathogenic, and do not produce harmful substances, they are considered ‘Generally Recognized As Safe’ (GRAS) by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and require no further approvals for use. That means companies are free to make claims about bacteria count with little regulation or oversight.”

To perform the study, the researchers bought two bottles of each of five major kefir brands. Bottles were brought to the lab where bacterial cells were counted and bacterial species identified. Only one of the brands studied had the amount of probiotics listed on its label.

“Just like probiotics, the health benefits of kefirs and other fermented foods will largely be dependent on the type and density of microorganisms present,” Swanson says. “With trillions of bacteria already inhabiting the gut, billions are usually necessary for health promotion. These product shortcomings in regard to bacterial counts will most certainly reduce their likelihood of providing benefits.”

The news release continues:

When the research team compared the bacteria in their samples against the ones listed on the label, there were distinct discrepancies. Some species were missing altogether, while others were present but unlisted. All five products contained, but didn’t list, Streptococcus salivarius. And four out of five contained Lactobacillus paracasei.

Both species are common starter strains in the production of yogurts and other fermented foods. Because those bacteria are relatively safe and may contribute to the health benefits of fermented foods, Swanson says it’s not clear why they aren’t listed on the labels.

Although the study only tested five products, Swanson suggests the results are emblematic of a larger issue in the fermented foods market.

“Even though fermented foods and beverages have been important components of the human food supply for thousands of years, few well-designed studies on their composition and health benefits have been conducted outside of yogurt. Our results underscore just how important it is to study these products,” he says. “And given the absence of regulatory scrutiny, consumers should be wary and demand better-quality commercial fermented foods.”

Zilber on Leaving Noma for Bioscience Corporation

A sustainable food industry will be built by flavor, says David Zilber, noted chef and food scientist.

Zilber made major headlines and surprised many in October when he left his job as head of the fermentation lab at Noma for a food scientist position at Chr. Hansen, a global supplier of bioscience ingredients. Noma, a two-Michelin star restaurant in Copenhagen, Denmark, has been regularly ranked one of the best restaurants in the world. In 2018, Zilber co-authored a bestselling book on fermentation with Noma co-owner Rene Redzepi.

In an Instagram live interview last week with Al Jeezera’s Femi Oke, Zilber elaborated on why he traded an apron for a lab coat. The global food system, Zilber says, is unsustainable. Waste is prevalent, food is created with long footprints, agricultural production is shrinking, meat is heavily consumed and large corporations control the industry.

Transforming Vegetables

“What I’m trying to do in my work is to make vegetables as God damn tasty as they can possibly be by using microbes, using things that are already at our disposal, and convincing people that this might have to have a little bit of a longer inventory life while you let it ferment, while you build a stockpile, but this is the result, this is why you’ll be able to convince people why eating this way is healthy for them and the planet,” he says. “Flavor is king.”

Ingredients created by Denmark-based Chr. Hansen (the company has 40,000 microbial strains used as natural ingredients) feed 1-1.5 billion people a day. These include microbes in yogurt and yeast in beer.

“I work with them to try and make the food system more sustainable, to get more people eating vegetables,” Zilber says, adding that 30% of every calorie consumed by humans is fermented by bacteria, microbes or fungus. “No matter what we eat in the future, that’s still going to be the case. That slot of the human diet still needs some form of microbial transformation, whether it’s meat or dairy or oat milk or peas. I work to figure that out.”

It’s a different philosophy compared to the food technology many new companies are utilizing to create alternative proteins like Beyond Burger. He complimented the company for their high standards, but he says a Beyond Burger patty is not a replacement for a juicy, beef burger. People pay more for an inferior eating experience.

“At the end of that day, that will not cut it,” Zilber says. “Why does food have to be that processed to be purportedly that delicious? With some skilled tricks in the kitchen, with some ninja jiu jitsu behind the stove, you can make vegetables really, really delicious.”

Sustainable Food Systems

A sustainable food system will look much like one from 300 years ago, Zilber hypothesizes. It will be localized, where people purchase food produced close by. Modern practices of shipping ingredients and processed food around the globe are harmful to the environment.

“A truly sustainable food system looks far more decentralized than [the current one] does right now. There are [only a] very few stakeholders that are responsible for really a lot of calories,” he continues.

Oke questioned how Zilber could change a broken food system controlled by large companies when he now works at one of the major companies.

“If you want to be an idealist, that’s great, you might end up being a martyr,” Zilber says. “Sometimes you have to work within those contradictory institutions to try to do as much good as possible.”

Restaurant Industry’s Responsibility

The restaurant industry plays a part in it too, Zilber says. Workers are stretched thin, overworked, underpaid “and then extremely vulnerable in a time of crisis.” The pandemic has exposed and highlighted these problematic parts of the restaurant business.

Zilber says there are still too many restaurants. It’s hard to find good cooks, and staff is often undertrained.

“I took a step into food production myself. Maybe more of these cooks, more of these people who are passionate about food, need to consider options beyond just the restaurant setting and see value in becoming a farmer, becoming a distributor, becoming someone who decides how those calories are made because restaurants aren’t the full picture of the food system,” he continues. “There are a lot of talented people within it who know food, who understand it, who understand the human experience of what it means to make good tasting food and satisfying food. There’s other places for them to work as well.”

- Published in Business

Fermented Sauce Market Growing

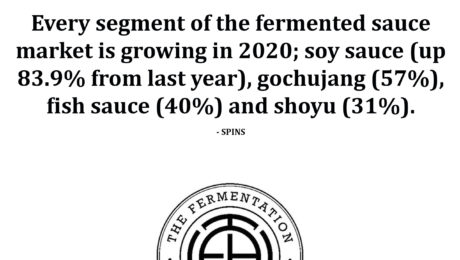

Every segment of the fermented sauce market is growing in 2020; soy sauce/shoyu is up 31%, tamari 33%, fish sauce 40% and gochujang 57%. – SPINS

- Published in Business

Oregon Fruit Releases Tangerine Fruit for Fermentation

Oregon Fruit Products added a new limited flavor to their lineup of Fruit for Fermentation purees. Tangerine joins aseptic fruit purees like boysenberry and grapefruit that fermenters can add to kitchen creations. Citrus flavors have become especially popular purees adds the co. sales director.

- Published in Business