Noma’s First Consumer Product Sells Out

Noma launched their direct-to-consumer food products line in February with a smoked mushroom garum. Their vegan spin on a traditional fermented fish sauce is the first release from Noma Projects, the famed restaurant’s product line for home cooks. That garum, retailing for $24 per 250cl bottle, sold out in a day.

“At Noma they’ve turned to koji and mushrooms instead of fermented fish to create their umami-rich smoked mushroom garum. It’s not as intensely salty as some other garum-adjacent products, and the aroma and flavor reveal subtle smoke and mushrooms,” writes Florence Fabricant of The New York Times.

Noma Projects — which launched last year — will include more pantry projects and community-based initiatives in the future, said René Redzepi, chef and co-owner of the Copenhagen-based restaurant. He hopes Noma Projects will him make more money. Noma has hovered around a slim 3% profit margin ever since opening 18 years ago.

Read more (The New York Times)

- Published in Business, Food & Flavor

The Dodo of Gastronomic History

Scientists are working to recreate an ancient garum, considered the “dodo of gastronomic history.” Beloved by Mediterranean civilizations, the fish sauce was thought by historians to be extinct, lost along with the Roman Empire.

Food technicians got new insight into this garum when archaeologists discovered sealed dolia (large clay storage vessels) at what is believed to be a former Garum Shop at Pompeii. The eruption of Mount Vesuvius buried the building, preserving the factory. The charred, powdered remains left in the vessels — plus a fish sauce recipe believed to have been from the 3rd century A.D. — has aided food techs in recreating the ancient garum.

This product uses heavily salted small fish fermented for one week with dill, coriander, fennel and other dried herbs in a closed vessel. The resulting “Flor de Garum” is sold in Spain by the Matiz brand in amphora-shaped glass bottles.

Top chefs in Spain have been using Flor de Garum in new dishes. Mario Jiménez Córdoba, chef at El Faro in Cádiz, uses it in black-truffle ice cream, a raw sea bass dish and chocolate ganache.

“When people think of garum,” Jiménez says, “they imagine something that smells disgusting. But we have to think of garum like we would salt, or soy sauce. You use only a few drops, and the flavor is incredible.”

Read more (Smithsonian Magazine)

- Published in Food & Flavor, Science

Noma Goes DTC

Noma is coming into the home kitchen.

The fermentation-focused restaurant, lauded as one of the top restaurants in the world, is selling its first line of packaged products. Two garums — vegan Smoked Mushroom and vegetarian Sweet Rice and Egg — will soon be available to ship internationally through the brand’s website, Noma Projects.

“It’s a space for us to channel our knowledge, our craft and experimentation into a new endeavor,” says René Redzepi, chef and co-owner of the Copenhagen-based restaurant.

Redzepi shared details of the launch in a video on the site. Noma Projects will include pantry products and community-based initiatives, “a way for us to address issues we care about through the lens of food.”

Noma’s Pantry Staples

The garums are Noma’s “take on a 1,000-year-old recipe that we’ve been developing over the past two decades.” Redzepi says the “potent, umami-based sauces” have been the “key to our success at Noma in our vegetarian and vegan menus.

He hopes the garums will help more people cook plant-based meals, announcing in the video: “We want to help you bring more vegetables into your everyday cooking.” The garums provide the flavor of meat and fish without the animal. The website description notes: “Shifting towards a more plant-based diet is the easiest way for an individual to help the environment. We hope these garums will do the same for you that they’ve done for us, help inspire and create more delicious plant-based meals when you cook at home.”

These products were developed in Noma’s Fermentation Lab, where dozens of pantry staples were tested before landing on the garums. A garum is the “concentrated essence of its main ingredient” with a strong umami flavor, and Redzepi describes it to the WSJ. Magazine (the luxury magazine published by Wall Street Journal): “It has the potency of a soy sauce, except it tastes of what it is.” Both are brewed with koji rice, what Redzepi calls the “mother fungus.”

The garums are currently fermenting and will be ready for shipping in the fall or winter. The expected price point is $20-$35 for a bottle.

And more garums are in the works. Noma Fermentation Lab director, Jason Ignacio White, says a roasted chicken wing garum is next.

“It tastes like super chicken stock with umami,” White tells WSJ. Magazine, ”so it’s a familiar flavor, but there’s something about it that you can’t really put your finger on, that makes your tongue dance.”

Improving Profitability

Despite Noma’s expensive tabs — the 20-course tasting menu costs 2,800 Danish kroner (or around $447), and the wine pairing is another 1,800 Danish kroner (or around $287) — in the 18 years since it opened, the restaurant has hovered at only a 3% profit margin. Redzepi hopes Noma Projects will make more money. While it is “a family-run garage project,” its goal is to reach a million customers.

Like many restaurants around the world, Noma shut down during the pandemic. They reopened as a burger and wine bar in June 2020, and the walk-up, outdoor dining experience was such a success that it became a permanent restaurant, POPL.

Noma resumed regular operations on June 1, 2021. The pandemic closure allowed Redzepi and his team to finally tackle the retail brand, something he said they had debated for years.

- Published in Business, Food & Flavor

Harnessing Fermentation for Sustainability, Part 2 of Our Conversation with Johnny Drain

In the second piece to our two-part Q&A with fermentation guru Johnny Drain, he details some of his recent fermentation consulting projects, as well as how (and why) more chefs need to use fermentation to create a sustainable global food ecosystem.

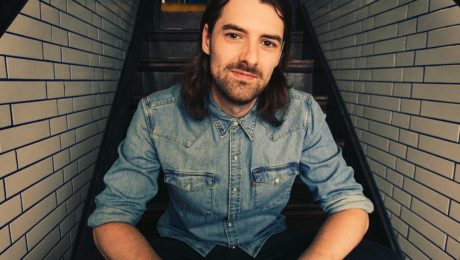

Drain works as a consultant for restaurants around the world, like Akoko Restaurant in London. Pictured, Drain poses with the team at Akoko. Akoko serves West African cuisine like dawadawa (fermented African locust beans) with ogiri egosi (melon seeds), a dish that shares similarities to natto.

TFA: The Cub Cave, where you’re currently working for Cub restaurant, tell me about it.

JD: That’s my “perma-lance.” But unfortunately, last week, we announced the Cub restaurant won’t be reopening after COVID, post lockdown.

The Cub restaurant is part of the Mr Lyan Group. So Mr Lyan (Ryan Chetiyawardana), he’s sort of this brilliant guy who typically operates in this world of cocktails and drinks, but also had this restaurant at the inception of food and drink. And Cub was really made to examine the inception of food and drink. The menu there was really this free-flowing journey through food and drink. So sometimes you’d have just a drink as a course, sometimes a food and a drink. It was really trying to break down this idea of why, even in the very best restaurants, have a food menu and a drink menu and they’re very separated. It was examining that intersection but also examining this intersection between luxury and sustainability. Why do you have to typically sacrifice sustainability when you have luxury and why do you have to sacrifice luxury when you have sustainability? So part of my time there, I set up the Cub Cave which was this R and D space literally below the restaurant in the basement, and I worked with chefs and the bartenders to essentially use that food waste, one, and in a deeper way examine ways that if there was an ingredient the chefs and bartenders wanted to use but perhaps they knew there would be a lot of trim or a lot of waste from it, I would go in and use my science smarts and find a way to use that trim. Basically to maximize the flavor that we extract from that produce we bring it.

There’s a famous American scientist of the 20th century, Richard Feynman, and when he was talking about nanotechnology, things at the nanoscale which are things that are atomically slightly subatomic which was my focus when I was a chemist and physicist, he famously coined this term “There’s plenty of room at the bottom,” meaning that there were plenty more technological applications in chemistry and physics.I like to say “There’s plenty of room in the bottom when we look in our bins.” Often what we throw away, pardon my French, there’s still shitloads of flavor in much of the food that we throw away. And it’s such a crying shame. My real role working with people like Cub in the Cub Cave and a restaurant called SILO, which is the UK’s first zero waste restaurant, is to look at what we’re throwing away and see what flavors are left. Then, use science and fermentation techniques to extract all that delicious flavor. When we’re talking about flavor, we’re talking about all the hard work, passion and dedication that some farmer has put in, or with animal products, the life some animal has given up to provide this product. The shame is that, often in most restaurants and bars, we would throw away much of it. There is still lots of flavor in there and how do we extract that flavor? Typically using fermentation.

TFA: Tell me more about SILO. What are some of the sustainability goals there?

JD: SILO was founded by this incredible guy called Douglas McMaster. He won British Master Chef Jr. when he was like 20, worked in a few restaurants around the world, then he had this epiphany when he was out in Melbourne working with this guy Joost Bakker, this zero waste pioneer. Doug had this mad idea of setting up this restaurant that had no bin. Which is kind of haughty if you’ve ever worked in a restaurant, you know how critical the bin is in a functioning restaurant or bar. The bin gets used several times a day. But Doug’s idea was to have a restaurant without a bin.

He set up a pop-up in Melbourne, then set up a brick and mortar restaurant in London called SILO. Really, Doug’s goal there is to be completely zero waste. A lot of that revolves around setting up relationships with the suppliers so that, when they drop off food or wine, either they drop off some type of pallet that goes back to get refilled or they drop it off in containers that can somehow be upcycled into some other product.

My goal in the SILO ecosystem is, if they do ever have trim, food trim usually goes to a composter, which is a viable and valuable use of food waste. But it’s a degrading, devaluing of the product. My role is to go in before the food has to go to compost, compost should be the last resort, and basically ferment it.

So we take things like dairy buttermilk when the guys make butter and we make this buttermilk garum, which is this incredible, golden-colored umami balm of a liquid, tastes of like blue cheese and toasted nuts, a little bit of caramel notes in there. We make this buttermilk garum and that goes on. Essentially buttermilk is a product that doesn’t have that great of value. But by fermenting it, the buttermilk garum has much greater value pound for pound than even the cream that started that process of making the butter. So we’re adding value back to the food chain and creating this phenomenal flavor profile that guests at the restaurants, even most chefs, no one has ever tasted because it’s a product no one else is making. The buttermilk, it went onto this slow cooked, aged dairy cow dish, and it also went onto this dish with brined tomato with sheep’s curd garnished with smoked grape seed oil, buttermilk garum and flowers. So we’re creating these incredible flavor profiles that blow people’s mind with this buttermilk garum which was born out of this necessity. How do we, if we’re going to make garum butter, which Doug wanted to do, we’re going to have lots of buttermilk. For every kilo of butter you make, you end up with about a kilo of buttermilk. It was born out of necessity and out of necessity, we’re creating this phenomenal, incredible, mind-blowing tasting ingredient.

TFA: Research shows that by 2050, when the global population is expected to reach 10 billion, we won’t have enough food to feed the growing population. How is our modern food system going to need to adapt to sustain our growing population?

JD: I think the first thing to point out is it will have to adapt. The course the industrial agricultural complex is heading, it’s completely not sustainable. It’s been based on this model of artificially-synthesized chemical inputs and fertilizers. Post World War II that was a necessity. It was innovative and smart and produced incredible yields, but it’s created a situation where the quality of the soil globally has degraded rapidly because of this, and we need to find different ways to nurture soil and produce or yield curves will just drop off.

We need to find ways to nourish soils, nourish ecosystems and create more resilient ecosystems and move away from this modern agriculture. But modern agriculture has been the prevailing paradigm for the last 30, 40 years. Sustainability has to be one of those cornerstones of the way we move forward. Sustainability has to be a tenant in all parts of the food system. We’re talking about from seeds, to how we grow food to the restaurant side, how can we take the foods we use and process it in a more sustainable way. That comes down to consumers being more savvy. They need to ask “I’ve got some cabbages in my fridge that look a bit funky and are starting to smell a bit, how can I use those?” Fermentation is one of those ways.

This is why fermentation popped up in the history of mankind. It’s a way of preserving the glut of food you had in summer and early autumn over the winters. Or it was a way of preserving, let’s say, dairy milk products. Milk sours off in 3-4 days, pre-refrigeration times, how do you preserve the very valuable nutrition that’s present in dairy milk for longer than that? So people started making butter, they started making cheese.

We’re going to harness some of those fermentation techniques as a way to extend the shelf life of those products that we have access to.

TFA: MOLD magazine, tell me how that came about.

JD: MOLD magazine, the name is potentially a bit of misnomer because it’s not just focused on mold. Although the first edition was focused on the human microbiome. But MOLD started off as a website which was started by a woman, LinYee Yuan. She’s a native of Texas, but now lives in New York and she’s an industrial designer by background. LinYee set up MOLD as a website to explore basically that intersection of food and design and where those meet. Some people might think that’s a bit of a weird marriage. What does food have to do with design? But in terms of everything we eat and all the utensils that we use to eat and the spaces we eat from restaurants to cafes, how our food is grown and processed and how it makes its way from farm to table, there have been design decisions made in all of those things. This interaction between food and design is very rich. And there’s a very deep, profound overlap between those two.

LinYee wants to explore that. She set up the website and we were set up between a mutual friend at a seminar a few years ago. She was looking for someone to create a print version of the work she’d been doing with the website. We came up with the idea of MOLD magazine.

We basically had this idea we’d do six issues of MOLD magazine, we worked with this incredible designer, Matt Sam and Erica Ko, who are based in North America as well. It basically explores one theme every issue. We’ve explored seeds, the human microbiome, food waste. We really go deep and we explore it from all aspects of the food side, the design side. The visual language we use in MOLD is very rich, it’s led by these brilliant designers we work with. It’s created as this print magazine in this world where most media we consume is online and we really wanted to create an object that you would sit down and get to grips with and immerse yourself in the experience of reading. It’s a limited print run, approximately 3,000 of each issue. But we’ve won lots of pleasing claudettes for the work. We were mentioned in the New York Times as one to watch. And we’ve worked with lots of great people. Massami Batora and Dan Barber wrote an article for us, all these great chefs. The response in the food world and the design world and the food tech world has been very positive to the work we’re doing and the ideas we’re sharing.

One of our core principles is that we want to use MOLD to give a voice to people that often in these conversations don’t have a voice. We are passionate about giving a voice to people who are underrepresented, people of color, women, basically using MOLD as a vehicle to give underrepresented voices a voice within these very important conversations around the world of food.

TFA: You spent time at Noma, working in the Nordic Food Lab. Your focus was exploring whether you can age butter like you age cheese. What was your conclusion?

JD: How I ended up there was completely bonkers. I had just finished my PhD. At that point I had no kitchen experience. I started working in the restaurants starging, which is basically, in the chef world, a French word which is to go and work for free for a week or two. I had started emailing people at these high-falutin restaurants that had these R and D facilities. One of which was this thing called the Nordic Food Lab which, to a degree, has been airbrushed from the history of Noma because of various politics. It started off, it was on this beautiful, big, Dutch barge in front of the old restaurant, Noma 1.0, which you could sort of see from the dining room. It started off as this food lab and test kitchen, and it became this food lab, this not-for-profit thing. Its mission was to kind of research Nordic cuisine and really elevate and amplify the work that Noma had been doing and find ingredients that could then go back into its menu. Eventually they kind of separated, the point where I was working there, the food lab was still on the Dutch barge outside the restaurant. (The Nordic Food Lab is now part of Copenhagen University.)

It was this incredible opportunity to work at the food lab, at a time when Noma was No. 1, on the world’s 50 best restaurant list, two Michelin stars, seen widely for various reasons as the world’s best restaurant, doing incredible things. As this guy who had worked mostly in sciences labs, which are very different from kitchens, to then suddenly be thrust into this environment of a world’s best restaurant, anyone who hasn’t been lucky enough to go to Noma, it functions in this very eclectic, choreographed way. It’s kind of this cross between this sort of military operation and a beautiful ballet where everything works kind of seamlessly. It’s a very beautiful spectacle to see a restaurant working at such a high level. To witness that, to be a tiny cog of this body working side by side with the restaurant, was an incredible experience and very inspiring.

I think the food lab really was responsible for a number of really important things within restaurant culture in the last 5 or 10 years. Rene Redzepi, who has done wonderful things for not just Nordic food but the whole food industry, I saw him speak in person a few times and he’s this very inspiring guy, he has this very powerful way of leading people and an incredible vision.

To cut to the question “Can you age butter?” Yes, you can. Basically, you end up with something that tastes like blue cheese. So you have these fermentation processes, this breakdown of these lipids, these fat molecules, into what we call free fatty acids. They are basically what gives flavor to a 36-month aged parmesan, which we all know and love. If you do that to butter, if you age butter, you get some of those same flavor compounds, and they’re present in parmesan, in aged comte. If you do it at just the right level, you get these kind of aged, spicy notes of a blue cheese or a delicious aged parmesan.

Unfortunately, aged butter hasn’t taken off in a way I thought it might, but certainly people are aging butters in a way they were 10 years ago. Hopefully, my work has encouraged people to investigate that in some small way.

Check out the first part of our Q&A with Johnny Drain here. To find out more information about Drain, visit his personal Instagram and the Instagram of MOLD magazine.

- Published in Food & Flavor

A Venn Diagram of Food, Biology & Chemistry: A Conversation with Johnny Drain

Johnny Drain is the guru for helping chefs around the world innovate flavorful dishes. A chemist with a PhD from Oxford and a passion for cooking, Drain found fermentation was the optimal intersection of food and science.

“Fermentation was this focus of this venn diagram that incorporated food with some necessity to understand biology but also chemistry,” Drain says. “Fermentation was this sweet spot where I could apply my background in science with this passion and knowledge and aptitude for cooking, flavor and taste. I realized if I wanted to apply this rich educational history that I was fortunate to have access to, fermentation was this ideal sphere where I could do that.”

This cross-section is where Drain finds his diverse career — as an in-demand food research and development consultant. He’s currently advising chefs in renowned restaurants all over the globe and serving as co-editor of MOLD magazine.

The Fermentation Association spoke with Drain, who is based in London. Below is the first of our two-part Q&A with Drain. Part 1 focuses on his interest in fermentation, and how he sees fermentation transforming the culinary world. Part 2 features some of Drain’s recent fermentation consulting projects and his drive to use fermentation to create a sustainable global food system.

The Fermentation Association (TFA): What got you first interested in fermentation.

Johnny Drain (JD): I am a scientist by background. I did chemistry as an undergraduate, then I worked for a company in finance, which I don’t really talk about. It was on the cusp of the financial crash, 2006-2008, so it was quite an interesting time to be working in that sector. During my lunch breaks, I was reading recipe books and reading restaurant reviews and looking at the world of science. I was thinking about doing a PhD, and I ended up quitting finance because I realized this was not how I wanted to spend my life, for 12 hours every day. I went back and did a PhD in something called material science, which is a cross between chemistry and physics. Still nothing actually to do with food, I was looking at how atoms interact in types of steel, and building computer models of how to understand that and how to apply that to making car chassis. So still, it was very far away from the world of making food, but always I had this dream of becoming a chef or maybe having a restaurant at one point in my life.

At the end of my PhD, I was fortunate to study in Oxford in this very beautiful place in the heart of England in this very rich academic history surrounded by all these very clever people and beautiful buildings. I realized, instead of becoming an Oxford don with maybe a tweed suit and patches on my elbows, I would sack that all in, having climbed up a few rungs of that ladder, and basically start staging (unpaid restaurant internship) and working in kitchens for free. I even worked as a pot washer in one kitchen in London. I really jumped back in at the deep end and pursued this dream of becoming a cook or a chef.

I did that for a little while and realized first, becoming a chef is a young person’s game. And second, I’m 6’2’’ and have a bad back and, as a chef, you’re standing on your feet all day and that was not going to be a physically viable way for me to make a living. I had to combine my scientific nouse (intellect) with my passion for food.

For me, the interesting thing is I never see these things as mutual exclusive, they’re all related and interconnected. I ended up doing what I do now, which is helping restaurants and bars and food brands, consulting and teaching restaurants and chefs how to understand these things. As I see it, I’m unlocking their artistry and storytelling ability through this understanding of science. All of these things are interconnected. And fermentation is this particularly excellent example. It has to do with flavor and food, but it also has to do with people and tradition and culture, it has to do with artistry and storytelling, you can’t really do one without the other. Science, that biology and chemistry, is really integral to unlocking the creative, artsy-fartsy elements to these types of food.

TFA: When you partner with these different chefs and kitchens, what expertise are they looking for from you?

JD: Especially these days, it’s different from five years ago when I first started doing this type of work. Five years ago when you’d go into a kitchen, people really wouldn’t know what fermentation was. And often they wouldn’t be interested in it, or they wouldn’t understand why might a scientist be able to help me make better, tastier food or drink. But now, most people I work with, they know that and they’ve already dibbled and dabbled a little bit with some of these ferments. Let’s say they’ve made some kimchi or sauerkraut or some kombucha. Really what they want now, especially the high end places, they’ve dibbled and dabbled and they want to make sure that, A, what they’re doing is safe and isn’t going to kill anyone, which is very sensible. But secondly, they want that kind of X factor, they want the ability to unlock that real deep magic. That’s when I go in.

I was just in Lithuania last week working with this really great restaurant called 1918. Michelin doesn’t cover Lithuania, give it two years I expect, and they’ll get at least 1 star, possibly 2. It’s really high end, great quality food. And they’re trying to play around with egg yolks and koji, which is basically this aspergillus, this war horse of Japanese food culture that’s also present in Chinese and Korean cultures as well. They want to be able to have that scientific rigor and have someone to come in “Pick that lock,” as I describe it, and be able to unleash their creativity so they can put this into action in their dishes. They’re wanting to tell these stories about Lithatian food culture and use this food they’re growing on this farm about 50 minutes outside the capital.

TFA: That sounds very rewarding, to help different restaurants create new dishes.

JD: It is. My role is this enabler, picking that lock, unleashing people’s creativity and helping these chefs. Really, fermentation is just a tool. In many ways, the way we see knife or a chopping board, it’s a tool. If you try and cook without those tools, you’re doing yourself a great disservice. You’re limiting what you can do, you’re limiting your creativity. Fermentation really is just another example of a type of tool. In five or 20 years, people will just see some of these fermentation techniques just as the way they see a knife. It’s just this tool. And by empowering these chefs with these tools, I’m helping to unleash that creativity. When you unleash people’s creativity they get very excited and very passionate.

TFA: Why do you think fermentation has become such a bigger interest among chefs?

JD: The funny thing about fermentation is we all eat fermented products, but we don’t realize it. You could read off a list that lasts five minutes. Bread, all booze, chocolate, coffee, vinegar, etc. It’s just that most of those products, we’ve become so used to them because there are these staples of everyday life that we don’t realize they’re fermented. Also partially because the way the food systems now work, that work of creating our own bread or beer or cider, it’s now been outsourced for most people in much of the world to some other party. So we’re not making these products at home where our grandmothers, our grandfathers, would have been. My grandmother would have understood that bread, wine, cider was a fermented product because she was making those or her grandmother was making those. Whereas I grew up in a household where we bought all of those things and somebody else made it. All those steps had already been performed.

First, there’s this awakening of realizing much of the food we know and love is fermented. And second, from a chef, foodie world, there’s been a renaissance in fermented food because they offer this exciting flavor profile that chefs always want. Chefs are looking for the new. Especially in the last 20 years, with that modernist cuisine movement, people reached science to kind of process foods. That’s where the novelness came. In the sort of last 10-15 years, we saw this move towards what new ingredients do we have on our doorsteps, foraging, this local-vore movement of people rediscovering what incredible food products are on their doorstep. Now people are asking “Where can we discover new flavors that are on our doorstep that are new, now that everyone has foraged everything. Where is the newness? Where can I reach out to access this incredible, novel flavor profile?” Fermentation is this toolkit that gives you access to these incredible new flavors. It’s the other frontier.

When you talk about what’s on our doorstep, we get into this idea of microbial territory.

What microbes are unique to Britain or unique to France or unique to Argentina? Actually, the microbes are as unique and defining of place and of the food culture in a place as the grapes that grow or the cheeses that we make or the strains of wheat varietals that might grow in a place. Microbes are sort of this hidden category of food that have shaped the food that we eat in the place that human beings live as much as any other kind of meat or dairy or fruit or vegetable.

TFA: What do you think is the future of fermentation in the culinary world?

JD: So the focus now is very much on people within the food industry looking for what produce they have in their backyard or in their country or their culture and how do they ferment those? I think, currently, the sort of toolkit of fermentation is dominated by a couple of prevailing techniques or cultures, microbiological cultures.

I think there is so much to learn from slightly undiscovered fermentation food cultures in the world. Ones that really haven’t had a bright light shone on them — like the Japanese, fermentation has had quite a bright light shone on them. And that’s amazing because Japanese fermentation culture is amazing and incredibly rich, so lots of people around the world have learned a lot from it. I think the next frontier for me is going to be people looking at fermentation in Sub-Saharan Africa, fermentation in the Indian sub continents. And those fermentation cultures are currently not that well understood, certainly by people outside those cultures, and they’re not documented in clear and concise ways in much of the way now that that Japanese food culture and Western European fermentation food culture has been documented. I think people are realizing there’s all these incredible, beautiful, rich ferments that we just don’t know about and don’t understand in Sub-Saharan African and the Indian subcontinents. I’m currently working on projects with people who are from those countries and cooking the food of those cultures. There’s just so much for us to learn.

TFA: What’s been the wackiest or funkiest food thing you’ve ever fermented?

JD: On the menu at one point at Cub (restaurant in London where Drain worked in research and development), we had a pest season where the head chef was trying to base the menu around things that are perceived as pests or invasive species.

In the UK we have this animal called the Reeves’s muntjac. It came originally from India. This guy called Reeves visited India as this colonizing force and came back and had, as a rich guy, a bunch of these species of flora and fauna as pets and novelties, one of which was this Reeves’s muntjac. It’s a very small, muscular deer. It’s bigger than a bulldog, but as muscular, then with a head of a deer and these horns. You see them driving along British country lanes at night and they look very scary, they basically look like devil dogs. They look like the harbingers of the apocalypse, sort of like something very bad is going to happen as you’re driving down the fog down this dark, British country lane. They’re very weird, scary and other worldly. They’re a pest and they outcompete the native species. So they are hunted to control their numbers.

So we made a muntjac garum. Using this technique of garum, which is a Roman word for fish sauce, we created this umami-rich, meaty garum. And that got used to dress these various, wonderful, meaty dishes. We did deer faggots. A faggot in the culinary sense of a word is the the offal of meat wrapped in the coals, part of the intestines, and basically pan fried. It’s a very traditional British dish. We made these deer faggots and dressed it in this muntjac garum.

That was quite a weird but delicious example of that whole 360 idea of sustainability in not just the techniques that we use but the produce we’re using. How do we use invasive species?

The conversation with Johnny Drain continues in our September 16 newsletter. To find out more information about Drain, visit his personal Instagram and the Instagram of MOLD magazine.

- Published in Food & Flavor

How Asian is Fish Sauce?

Food historians, chefs and nutrition experts are divided: could Asian fish sauce have come from Ancient Rome through the Silk Road? There are numerous similarities between the Roman condiment garum and Asian fish sauces, highlights an article in the South China Morning Post. Garum — made by layering salt and fish — was the second most expensive liquid on the market after perfume. Another theory says the local Asian fish sauces like Vietnam’s nuoc mam, Thailand’s nam pla and Japan’s gyosho were not influenced by Roman garum but by China’s ancient soy sauce making. Sauces like nuoc mam use the same fermentation technique as Chinese soy sauce, and they share the same consistency.

“Fermented fish sauces and dishes from different periods and places around the world show that various civilizations have found fermentation to be the best and easiest way to preserve food,” says Giorgio Franchetti, food historian and author of the book “Dining with the Ancient Romans.”

Read more (South China Morning Post)

- Published in Food & Flavor

Noma Reopens as Walk-In Burger, Wine Bar

The world’s most famous fermentation restaurant is serving diners once again during the coronavirus pandemic. But Noma’s reservation-only tables and $400-500 world-class meal has radically changed. Noma is now serving wine and burgers in a walk-up, outdoor patio.

“It’s definitely new territory,” says Rene Redzepi, Noma founder. “I like this thing that it’s doing to us. We’ve become this place where you book, you plan your travels six months ahead of time. The spontaneity of going to a restaurant has completely disappeared for us. I like that people now can say ‘Let’s go to Noma for a glass of wine.’ So who knows, maybe this is part of our future in the long run.”

Redzepi spoke with Denmark-based food bloggers Anders Husa and Kaitlin Orr on Noma’s reopening.

The Noma burger is either a meat patty made with beef ferment, beef garum and smoked beef fat or a veggie burger made with quinoa tempeh patty with fermentation liquids.

Noma’s Nordic cuisine features fermented and foraged food that have earned Noma the World’s Best Restaurant award four times. Noma has been closed since March 14 because of the coronavirus.

Redzepi is one of the first chefs of his caliber to reopen a fine-dining restaurant during the coronavirus pandemic. The burger and wine menu is intended to transition Noma to the July summer season, when the restaurant hopes to again serve diners in the restaurant.

When the coronavirus first shutdown countries all over the globe, Redzepi said “it was really, really scary.” Would Noma have to wait six months to open? A year? About 3-4 weeks in, though, the atmosphere turned.

“There was a little positivity coming through,” Redzepi said. “I started asking myself ‘What do I want to do? What am I missing in my life?’ And the funny thing is I wasn’t at all missing going to a fine-dining restaurant, sitting for 3-4 hours. That was not on my mind at first. I wanted to be with people, I want to be out. … So when you have that feeling, it was just like, there was no way we can open Noma as it was before COVID-19.”

It’s an unusual sight at the exclusive restaurant – Noma is serving burgers in paper wrappers and chefs are wearing disposable gloves.

A burger was picked because Redzepi says: “I have yet to meet anybody that doesn’t like a burger.” In the future, Noma will add a deep-fried chicken burger to the menu as well as oysters and shrimp.

As tourism is still closed in Denmark, Redzepi envisions the new Noma bar as a place where Copenhagen locals can eat and visit with friends again.

“It’s not about us showing what we can do, it’s just about cooking the best we can so people feel great and feel alive again.”

- Published in Business

Chef Explains Why Umami and Garum Are Key to Delicious Veggie-Based Dishes

You’ll never find Jon Bertolone, chef of Nourish in Oregon, serving an Impossible Burger. He says there are other ways to be inventive with a savory, plant-based patty. “Umami is something that has sort of driven my culinary journey,” Bertolone says. He’s been experimenting with garum (fermented fish sauce) to capture beef flavor, too. Fermentation, Bertolone says, is “the key to bridging cultures, because every culture has them.”

Read more (The Register-Guard)

- Published in Business, Food & Flavor