The Microbes We Should (or Shouldn’t) Be Eating

How important are microbes in the human diet? And does it matter which ones we eat?

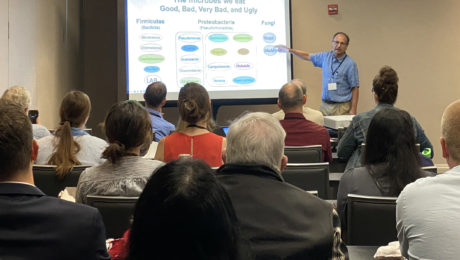

“Maybe we’re not too far from proving the following; the dietary guidelines, the My Plate guidelines, should include fermented foods, including those that contain live microorganisms, as part of a healthy diet,” says Bob Hutkins, PhD, a professor at the University of Nebraska (and TFA Advisory Board member). Hutkins explored this hypothesis during his standing-room only presentation at FERMENTATION 2022 titled The Microbes We Should (or Shouldn’t) Be Eating.

He estimates, just like the daily fiber recommendations were granted based primarily on epidemiological studies, fermented foods are going through the same process. And one day there may be a daily fermented food recommendation.

Why Should We Be Eating Live Microbes?

Highly processed foods, prolific use of antibiotics, and overly hygienic environments have resulted in significantly less exposure to microbes. This includes those microbes that help to maintain a healthy gut microbiome and that keep our immune system functioning properly. Indeed, according to the so-called Old Friend’s Hypothesis, exposure to microbes is necessary for proper development of the immune system. This is especially true for Western countries. One highly-cited study published in Lancet found Inflammatory Bowel Diseases (IBDs) like Crohn’s Disease and Ulcerative Colitis — “are predominantly associated with Western populations. You rarely see these diseases in other parts of the world,” Hutkins says.

“In the Covid era, we have certainly learned that preventing infectious diseases remains a major challenge, and being a bit germophobic is understandable. Certainly, modern food technology that includes pasteurization has significantly reduced pathogen risk, improved food safety, enhanced shelf life, and reduced food waste. Nonetheless, our environment has often become too clean, too hygienic and we are no longer exposed to microbes,” he adds.

Another study based on research in Finland found the Old Friend’s Hypothesis holds true for development of allergies, asthma, and eczema. As the authors noted “changes in environment and lifestyle, affecting microbial exposure and immune regulation, seem to play a major role in the so-called post-war allergy epidemic”. Indeed, in a 2002 editorial in the New England Journal of Medicine, three “old-school” lifestyle approaches were mentioned for protecting against the development of allergies: supplementing with lactobacillus (the bacteria found in fermented foods), owning a dog in your home and attending daycare.

Consuming Live Microbes Benefits Human Health

To address this situation, Hutkins and other food scientists are proposing adding fermented foods to the Recommended Dietary Guidelines, along with the daily dose of nutrients and vitamins.

“One of the main challenges however, will be to distinguish between nutrients and microbes,” Hutkins says.

The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) has explored this further. A panel of ISAPP microbiologists, nutritionists, doctors and statisticians (including Hutkins) used the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) to deep dive into the American diet. The NHANES database catalogs what adults and children are eating, then collects health indicators for associated diseases.

ISAPP researched the estimated live microbes in foods to find sufficient evidence that a live dietary microbe intake should be a part of a dietary recommendation. It was a big undertaking, since there are 9,388 foods inNHANES. ISAPP ranked each food’s microbial count. They found microbial count was low for processed, heat-processed foods, medium level for fresh fruit and vegetables and high for fermented foods, like fermented dairy (yogurt, fresh cheese) and fermented vegetables.

“Ninety-six percent of the foods we eat are in the low” count for microbes, he said. “Hardly any were in the fermented category, around one percent.”

Still, not all live microbes are the same. The microbes considered healthy – lactic acid bacteria and bifidobacteria – are only dominant in fermented foods. Most of the live microbes consumed in the average diet are proteobacteria from fresh fruits and vegetables.

The Institute for the Advancement of Food and Nutrition Sciences, which catalogs nutrition labels for all USDA food data, now has a space for a brand to enter the amount of live microbes in their product. There’s a dropdown menu to add genus and species of a probiotic strain, too.

“This new effort is a way to introduce the live microbes in the database,” Hutkins says, noting a company would have to enter it voluntarily. “They’re offering a noncompetitive, objective, transparent mechanism for stakeholders to understand live microbe intake and eventually link intake to health outcomes.”

Fermented Foods Reduce Stress

Researchers have made a breakthrough discovery in stress management: fermented food can change one’s mood.

Scientists from the University College Cork (UCC) APC Microbiome research center found consuming 2-3 servings of fermented foods a day – like sauerkraut, kefir, kimchi, kombucha, yogurt, etc. – improves mental health. Stress and depressive symptoms are reduced when regularly consuming fermented foods.

Their month-long study analyzed the effects of a psychobiotic diet on adults, while the control group was given general nutrition advice in line with the food pyramid. The psychobiotic diet is designed to target the gut microbiome. It includes fermented foods, fruit and vegetables high in prebiotic fibers, grains and legumes.

“Although the microbiome has been linked to stress and behavior previously, it was unclear if by feeding these microbes demonstrable effects could be seen,” said Professor John Cryan, one of the study’s lead authors, vice president for research and innovation at UCC, and a principal investigator at APC Microbiome. “Our study provides one of the first data in the interaction between diet, microbiota and feelings of stress and mood. Using microbiota targeted diets to positively modulate gut-brain communication holds possibilities for the reduction of stress and stress-associated disorders, but additional research is warranted to investigate underlying mechanisms.”

Researchers studied participants with relatively low fiber diets, measuring their perceived levels of stress before and after beginning the psychobiotic diet. Four weeks in, participants reported a strong decrease in perceived stress. Their sleep improved, too. Forty chemicals were affected by the change,

“These results highlight that dietary approaches can be used to reduce perceived stress in a human cohort. Using microbiota-targeted diets to positively modulate gut-brain communication holds possibilities for the reduction of stress and stress-associated disorders,” the study reads.

Cryan, in an article for The Telegraph, said: “The mechanisms underpinning the effect of diet on mental health are still not fully understood. But one explanation for this link could be via the relationship between our brain and our microbiome (the trillions of bacteria that live in our gut). Known as the gut-brain axis, this allows the brain and gut to be in constant communication with each other, allowing essential body functions such as digestion and appetite to happen.

“It also means that the emotional and cognitive centres in our brain are closely connected to our gut.”

He added: “The next time you’re feeling particularly stressed, perhaps you’ll want to think more carefully about what you plan on eating for lunch or dinner. Including more fibre and fermented foods for a few weeks may just help you feel a little less stressed out.”

The study was published in Molecular Psychiatrry.

Educating Consumers About Fermentation

Fermentation continues to top food trend lists, health movements and restaurant menus, influencing more curious consumers to buy fermented foods. But the average consumer remains fermentation clueless.

“Fermentation is a really complicated subject and we’re just reaching the tip of the iceberg at this point when it comes to the research,” says Jenna Mills, account manager at Eat Well Global, a food and nutrition consulting agency. “A complicated subject like this is loaded and I feel that individuals and consumer know just enough to be confused.”

Five food professionals shared their thoughts on how to educate consumers about fermentation during a panel at FERMENTATION 2022. Panelists included: Mills, Shannon Coleman (associate professor and state extension specialist at Iowa State University), Matt Lancor (CEO and founder of Kombuchade), and Kirsten Shockey (author, educator and co-founder of The Fermentation School and TFA Advisory Board member). Amelia Nielson-Stowell, editor at The Fermentation Association, moderated.

Simple Messaging

The panelists agreed fermentation brands need to stop overcomplicating fermentation to the consumer, focusing on simple communication strategies.

“I compare it to a small child asking where babies come from – a simple answer is enough,” says Shockey. “With fermentation, often, we’re ready to say that lactic acid bacteria come in and they’re eating carbohydrates and there are these metabolites and flavors involved. We’re ready to share all the details – and we’re met with a blank stare. People just often want to know what’s the difference between a pickle and a ferment.”

Shockey, who teaches at the women-run Fermentation School, says she’s felt pressure over the years to innovate her classes and teach new subjects. But, especially since the Covid-19 pandemic when more consumers focused on health and turned to fermentation, her most popular classes are still the basic fermentation 101.

In a TFA survey last year, 70% of fermentation producers said a greater understanding of fermentation and familiarity with the flavors associated with fermentation would foster increased consumption of fermented foods.

Kombuchade is taking a unique approach to that education component, focusing on kombucha as a recovery drink.

“I’m looking to make probiotics cool for athletes, much like Gatorade made electrolytes cool for athletes,” Lancor says. The science of food is typically a mechanical process: eat fats, carbohydrates and proteins for optimal energy and performance. “There’s actually a microbial fermentation process that’s helping to rebuild your muscles.”

Kombucha marketing is geared toward a yoga, enlightenment crowd, Lancor adds, only reaching a certain number of consumers. It doesn’t resonate with all consumers.

“The south side of Chicago guys that play on my rugby team, they were never going to grab that kombucha bottle off the shelf with that kind of messaging,” he says. “There wasn’t this message of probiotics can be used for performance or recovery or even understanding kombucha’s place within an athlete’s regimen.”

Communicating Science & Tradition

Fermented food brands are tasked with bridging the gap between science and consumer.

Consumers keep informed about food and nutrition trends through professional associations (69%), academic (67%) and dietitians and nutritionists (62%), according to a consumer insights survey by Eat Well Global.

For 77% of consumers, the advice of dietitians and nutritionists impacts which foods they buy. Mills says healthcare professionals offer that counseling on how to incorporate fermented foods into the diet.

Don’t forget the ancestral wisdom, Shockey points out.

“My one liner is we’ve evolved with these foods and you are here because your ancestors successfully fermented,” she says. Rather than educating that people should eat a tablespoon of sauerkraut a day to meet nutrition needs, “try to bring it into your world naturally.” Eat a mixture of ferments, with yogurt at breakfast or hot sauce at lunch and kimchi at dinner.

“We cannot put ferments into this box that must be eaten raw. That to me is a barrier. You should eat this in any way that feels right to you,” she says, adding ferments were traditionally eaten cooked in soups and stews. “But in our minds right now is the idea that we have to eat our probiotics raw. These foods have so many metabolites that are being created in production and they follow through in the cooking process.”

Challenges to Starting a Brand

Starting a fermentation brand can be an overwhelming task. Sandor Katz, fermentation author and educator, said in his keynote address at the FERMENTATION 2022 conference that education is a huge challenge for people launching new fermented products.

“They often end up putting a lot of their energy into educating consumers,” he says.

Coleman says state extension offices are an underutilized resource for new producers. Her office got into food preservation after noticing many Pinterest recipes that gave poor advice on food safety.

“Just about every extension program has some form of food preservation type of program that they are delivering to consumers and they want to help,” Coleman adds.

There are no universal standards for labeling, an obstacle for new producers.

“Labeling is such a sensitive issue because you can get into big trouble with the FDA,” Nielson-Stowell says, pointing out the U.S. Food & Drug Administration only has 12 approved health claims a brand can put on a label. “It also gets tricky putting ‘probiotic,’ ‘prebiotic’ or ‘postbiotic’ on a label. It’s not regulated and confusing to consumers.”

The International Scientific Association of Probiotics & Prebiotics (ISAPP) is pushing for -biotics to be a more protected term. According to ISAPP, only fermented food brands with a scientifically measured -biotic should but it in a label. Their health benefits must be documented. For example, yogurts often have defined probiotic strains on their labels.

Nielsen-Stowell recommends using “live cultures,” “live microbes” or “naturally fermented” instead. And make sure retailers know what that means.

“If you’re getting your set in store with a retailer, the retailer will be your biggest advocate. The retailer is going to be the one talking to the customers more than you. Educate them. Do they know why your product is better than your competitor’s product?” she adds.

Pass the Protein Powder – and the Ferments?

Fermented foods can aid in muscle growth.

“A growing body of research suggests gut-friendly foods enhance muscle growth and could even take a bite out of age-related decline,” reads an article in Men’s Health.

As we age, the body slows down, reflexes decrease and muscle mass decline — especially difficult changes for professional athletes. The average person loses 5% of muscle mass per decade after reaching 30, leading to diminished mobility and heightened risk of falls. Exercising consistently is key to keep muscles strong. But equally important, research shows, is maintaining a healthy gut microbiome. New research – published in the journal Nutrition and Metabolic Insights – found mice with an artificially depleted microbiome from antibiotics had significantly slower muscle growth than the control group.

“In short, muscles really are built in the kitchen – at least, to a greater degree than you might have suspected,” the article continues.

The article points to the ground-breaking Stanford study that found a diet high in fermented foods boost microbiome diversity. The article concluded with four fermented food swaps “to make your gains last.” These include: swapping yogurt for kefir, swapping green beans for natto, swapping pickles for kimchi and swapping ketchup for miso.

Read more (Men’s Health)

- Published in Business

Promoting Fermentation Innovation

Several obstacles prevent the innovation of fermented foods, from the lack of scientific research to a chasm between science and industry to improving the sustainability of traditional ferments.

A third of foods consumed worldwide are fermented, totalling 3,500 products. A group of European scientists is studying how those fermented foods can drive innovation in food systems.

“There’s not a clear way to improve the unique properties of traditional fermented foods using microbial organisms,” says Vittorio Capozzi, PhD, a researcher with the Institute of Sciences and Food Production (ISPA) in Italy. “We still need innovation in traditional fermented foods.”

Capozzi was one of the presenters at a side event during the October Food & Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Science and Innovation forum. PIMENTO hosted the session. PIMENTO (which stands for “Promoting Innovation of ferMENted fOods”) launched last year in Europe, a project of the European Cooperation in Science and Technology (COST). PIMENTO aims “to place Europe at the spearhead of innovation on microbial foods” by promoting fermentation’s health, diversity and production. To achieve this goal, five working groups are structured around different fermentation topics. The groups are made up of both scientist and non-scientist fermentation experts studying and eventually implementing their findings.

Traditional ferments have “an important part of biodiversity that we cannot neglect,” Capozzi says. Fermentation provides new microbial-based solutions for a variety of foods, from plant-based ferments to alternative proteins. Innovations can improve nutrition and sensory qualities.

“In this way we are preserving biodiversity that has huge potential in biotechnology, science and innovation,” he says.

Ferments, he notes, can be protected. For example, a ferment produced in a specific geographical region (tequila in Mexico), a protected diversity, vegetable type, animal product or the human behavior used in production (Salers cheese in France).

“Fermented foods have been shaped through the centuries,” says Effie Tsakalidou, professor at the Agricultural University of Athens in Greece. “We have a lot of diversity.”

One of PIMENTO’s tasks is to create a database on European fermented foods. This list would include food types, production, consumption volume, technological parameters and legal status (like certifications).

Speaking on the health benefits and risks of fermented foods, Smilja Todorović, PhD, a professor at the Institute for Biological Research in Serbia, notes there’s a dearth of reputable, peer-reviewed studies on fermented foods.

“One of the very important things is to identify gaps in scientific evidence regarding benefits and risks,” she says.

The current studies on fermented foods are few and limited. Research does prove consuming fermented foods is correlated with overall mortality, decreased risk of diabetes, certain cancer types, high blood pressure and cardiovascular diseases. Todorović says that’s not enough.

“Unfortunately, when we look at scientific evidence to claim health properties, we can see that there are insufficient evidence. So all we have is a growing scientific interest in fermented foods and their impact on human health. However, we need to move from promising results to scientific evidence,” he says.

PIMENTO’s working groups are cataloging fermented foods’ impact on the gastrointestinal symptom, allergies, immunity, bone health and neurological projects. They also plan for projects studying fermented foods bioactive compounds, vitamin production and functionality; and fermented foods use in personalized diets.

The lack of studies prevents innovations in the field. Antonio del Casale, co-founder and CEO of Microbion, an agro-industrial microbiology company, says there is a disconnect between the scientists studying fermented foods and fermented food producers. He calls it “a valley of death.” The research on fermented foods is low, but the development of commercial resources are increasing.

“The problem is how to avoid the limitations of developing the food in this sector,” he says.

Using Genomics to Improve Beer

A group of Belgian scientists have not only identified the gene responsible for much of the flavor of beer and other alcoholic beverages, they’ve also engineered it for brewers.

By screening large numbers of yeast strains, researchers were able to identify the genes responsible for beer’s flavor.

“To our surprise, we identified a single mutation in the MDS3 gene, which codes for a regulator apparently involved in production of isoamyl acetate, the source of the banana-like flavor that was responsible for most of the pressure tolerance in this specific yeast strain,” said Johan Thevelein, Ph.D., an emeritus professor of Molecular Cell Biology at Katholieke Universiteit, and one of the researchers. His team pioneered the technology that identifies the genes responsible for commercially important traits in yeast.

Important to the study was finding the gene successful at creating flavor on a commercial scale. Modern, large-scale beer brewers use tall, cylindrical fermentation tanks compared to the traditional shorter vats. While the taller tanks are easier for brewing, it negatively impacts the beer’s taste. That’s because, when beer ferments, the yeast coverts 50% of the sugar in the mash to ethanol and the other 50% to carbon dioxide. But carbon dioxide pressurizes in the modern closed vessels, dampening flavor.

Using the gene editing technology CRISPR/Cas9, Thevelein and his team were able to engineer the MDS3 gene for other brewing strains, improving their tolerance of carbon dioxide pressure and improving the flavor.

“That demonstrated the scientific relevance of our findings, and their commercial potential,” Thevelein added in a statement.

“The mutation is the first insight into understanding the mechanism by which high carbon dioxide pressure may compromise beer flavor production,” said Thevelein, who noted that the MDS3 protein is likely a component of an important regulatory pathway that may play a role in carbon dioxide inhibition of banana flavor production, adding, “how it does that is not clear.”

The technology has also been successful in identifying genetic elements important for rose flavor production by yeast in alcoholic drinks, as well as other commercially important traits, such as glycerol production and thermotolerance.

The results of their study were published in Applied and Environmental Biology, the journal for the American Society for Microbiology.

- Published in Science

Consumers: We’d Eat More Fermented Foods if Knew Health Benefits

The general public lacks knowledge of fermentation and does not understand the health benefits. Nearly 85% of respondents in a survey said they would consume more fermented foods if they knew more about fermentation’s health benefits.

The study illustrates much work is needed in educating consumers. Over 83% of respondents didn’t know the definition of fermentation and over 60% had limited knowledge of the microorganisms involved in fermentation. Most learned about fermented foods at school (31%), the internet (29%) or home (26%). And 72% said they felt safe consuming fermented foods.

Researchers from the University of Maribor in Slovenia studied how much people in the country know about fermentation. The results were eye-opening, especially since fermentation is more common in Europe. The study notes Slovenians commonly grow up eating local fermented foods, like sauerkraut, sour turnip and sour milk, especially in rural areas.

“Despite the fact that less than one fifth of the participants were familiar with the definition of fermentation and understood the process, almost one-third of the participants at least tried to ferment at home,” the study concludes. “Fermented foods should once again become part of the diet to improve overall health and reduce or postpone the onset of a variety of chronic diseases that plague us today.”

Read more (BMC Public Health)

Inuit Scientist on Ferments of the Arctic

When Aviaja Lyberth Hauptmann, PhD, began her research into the metagenomics of snow and ice environments, she was surprised that plant-based diets were a constant focus in the field of human gut microbiome research.

“I wondered why no one seemed to acknowledge that some peoples, and in particular Arctic Indigenous peoples, have lived healthily off animal-source foods for millennia,” she says. “It was clear to me that there is a large gap in our understanding of how healthy animal-source foods affect the microbiome. And not just animal-source foods, but foods that are not industrially produced, foods that come straight out of our environment, including microbes from our environment.”

This has become central to Hauptmann’s research. She’s published two papers on Inuit foods. Her latest, on Inuit ferments, was published with Maria Marco, PhD, food science professor at University of California, Davis (TFA Advisory Board member). That study, published in the journal Microbiome Research Reports, concluded the way to “understand the value of these traditional animal-sourced foods” is to combine new microbiological techniques with projects led by the Inuit “who make and consume fermented foods.”

In an interview with Microbiome Research Reports, Hauptmann notes that most people consider the Arctic a harsh, barren and cold place. “But Inuit describe the vast sea ice as some might describe a garden. It is full of life and food. The Arctic is a source of diverse and abundant diets if one knows how to tap into the abundance and diversity, and an important aspect of that is food preservation and of course fermentation.” Inuit store meat and other food when it’s been abundant, so fermentation has played a central role for the last 300 years. She hopes Inuit people will still take part in that local culture, eating and preserving the local foods.

Read more (Microbiome Research Reports)

- Published in Food & Flavor, Science

Nourishing Microbiota With Fermented Foods

The gut microbiome and how fermented foods can nourish it topped the Washington Post headlines in September. The article shared highlights from the growing number of studies that suggest “these vast communities of microbes are the gateway to your health and well-being — and that one of the simplest and most powerful ways to shape and nurture them is through your diet.” Food (and environment and lifestyle behaviors) have a much larger impact on the gut microbiome than genetics.

The article by health reporter Anahad O’Conner says science proves diverse diets make diverse gut microbiomes. Lower rates of microbiome diversity is linked to chronic diseases like obesity, diabetes and rheumatoid arthritis.

One way to increase that diversity is by eating fermented foods – the article points out yogurt, kimchi, sauerkraut, kombucha and kefir as excellent examples.

“The microbes in fermented foods, known as probiotics, produce vitamins, hormones and other nutrients. When you consume them, they can increase your gut microbiome diversity and boost your immune health, said Maria Marco, a professor of food science and technology who studies microbes and gut health at the University of California, Davis.”

A study by researchers at Stanford – and published last year in the journal Cell – found people who eat fermented food regularly increase their gut microbial diversity and lower their levels of inflammation.

“While it’s clear that eating lots of fiber is good for your microbiome, research shows that eating the wrong foods can tip the balance in your gut in favor of disease-promoting microbes,” writes O’Connor. The “bad” microbes, according to research, are commonly found in highly processed foods “that are low in fiber and high in additives such as sugar, salt and artificial ingredients. This includes soft drinks, white bread and white pasta, processed meats and packaged snacks like cookies, candy bars and potato chips.

Tim Spector, professor of epidemiology at King’s College London and the founder of the British Gut Project, tells the Washington Post that eating a wide variety of plants, fiber and nutrient-dense foods is also beneficial for the gut. Spector encourages people to eat 30 different plant foods a week, which can include produce, nuts, herbs and spices.

Read more (The Washington Post)

The Flavor Whisperer on Fermentation

Flavor is much more complex than just taste. Flavor can be collected, extracted, infused, created and transformed. And, in a billion-dollar flavor industry devoted to putting flavors into processed foods, fermentation is the oldest and most natural flavor creator, developing new flavors at a molecular level.

“Fermentation as a flavor creation process in collaboration with microbes, there’s almost no limit to how you can apply it and use the ingredients around you and have a more flavorful palette to work from,” says Arielle Johnson, PhD, a flavor scientist, gastronomy and innovation researcher and co-founder of the Noma Fermentation Lab.

A food chemist dubbed the flavor whisperer, she works with restaurants on innovating dishes and cocktails. She researches how flavor is perceived and is writing a book on her studies, Flavorama. Her work comes together in “all things science and cuisine have to say to each other.”

This week Johnson shared her insights into flavor and fermentation as a guest lecturer at Harvard University’s Science & Cooking series.

Taste & Smell Receptors

Flavor can be quite complex – Johnson calls it a black box.

There are five primary tastes: sweet, sour, salty, umami and bitter. Each taste evolved to ensure humans get basic nutrition. We use sweet foods for the energy in sugar, sour ones for vitamin C from fruit and fermented foods. Salty foods provide the essential mineral sodium. We seek umami foods for the taste of glutamine, an amino acid in proteins and fermented foods.

But bitter, Johnson points out, doesn’t sense one thing. It senses multiple molecules that are potential toxins for us. This is why bitter is called an acquired taste.

Smell is Johnson’s favorite part of the flavor profile. In order to taste, we must smell, too. Molecules land in the olfactory receptors in the nasal cavity and help activate taste. This is why food is tasteless if you plug your nose while eating. But the back of the throat is also connected to the nasal cavity, so the throat becomes “the secret backdoor” for sensing flavor.

While there are five major tastes and four receptor areas on the tongue, there are 40 billion smellable molecules and 400 receptors for smell.

Supertasters vs. Nontasters

Taste and smell, she detailed, help us understand how fermentation works.

The population can be divided into supertasters or nontasters. During her presentation, Johnson had the audience put a strip of filter paper on their tongue. The paper included a harmless bitter molecule phenylthiourea (PTC), but only roughly half the class could taste it. This group are supertasters – the group who could not taste the PTC are nontasters.

She explained everyone has different density of their taste buds. Supertasters have more taste buds, so more taste receptors signals are sent to their brains. This has culinary implications. Because their sense of taste is more sensitive, flavors are intense and supertasters have a less adventurous palette. Meanwhile nontasters have dulled senses, so it takes a lot of flavor to activate taste.

“The good news for supertasters is that fermentation is usually salty and sour and often umami – all of which counteract bitterness,” Johnson says. “Fermentation is a way to create new flavors but also transform ingredients.”

Fermentation as Flavor

Though “microbes are opportunistic” and pop up in foods whether planned or not, fermentation can’t be forced, Johnson says. When making a sauerkraut, for example, microbes don’t need to be added. Fermentation works with what’s on the surface of the cabbage and on the producer’s hands.

Salt is key in fermentation as a flavor additive, a preservation element and a safety measure. Salt filters out bad molds and avoids letting a ferment spoil. Other factors “dial in the flavors in this molecular flavor creation process,” she says, like the correct ingredients, temperature control and humidity.

“We’re really excited about microbes and fermentation,” Johnson says. “In this process of this exponential growth that microbes do, they’re eating things, they’re getting energy, but they’re also running their regulator metabolism. So there’s all these waste products that are not very significant to the microbes, but that can create a lot of interesting flavor complexity.”

- Published in Food & Flavor, Science