More Than One SCOBY?

A SCOBY is the gelatinous bacteria colony central to making kombucha. But did you know there are four different types of SCOBY? Scientists at Oregon State University spent the past four years researching the microorganisms that contribute to the tea fermentation that produces kombucha. The results of their work were published in the journal Microorganisms.

SCOBY is a challenging mystery to many kombucha brewers. Little is known about how SCOBY impacts flavor. The OSU scientists aim to help kombucha brewers make a more consistent product.

“Without having a baseline of which organisms are commonly most important, there are too many variables to try and think about when producing kombucha,” says Chris Curtin, an assistant professor of fermentation microbiology at OSU. “Now with this research we can say there are four main types of SCOBY. If we want to understand what contributes to differences in kombucha flavors we can narrow that variable to four types as opposed to, say, hundreds of types.”

Curtin and doctoral student Keisha Harrison used DNA sequencing to evaluate the microorganisms in 103 SCOBYs used by kombucha brewers (primarily ones in North America). The four SCOBY types each use different combinations of yeast and bacteria.

Read more (Oregon State University)

- Published in Food & Flavor, Science

Dunkin’ Kombucha

Move over, Dunkin’ Coffee. The chain known for its coffee and donuts is branding itself into new territory — kombucha. Dunkin’ is the first chain restaurant (to TFA’s knowledge) to make their own kombucha. They are testing their new Dunkin’ Kombucha — made in two flavors, Fuji Apple Berry and Blueberry Lemon — in select restaurants in the Albany, N.Y., and Charlotte, N.C., markets.

According to their release, “Dunkin’ continues to democratize delicious by testing kombucha for the first time.” In any case, this test is further evidence of the fermented tea’s increased popularity as an alternative to soda.

Read more (Dunkin’)

- Published in Business

Syn-SCOBY

Engineers at MIT and the U.S. Army Research Lab have developed what they call Syn-SCOBY, a living material made from laboratory yeast and bacteria. Similar to a kombucha mother, it is a tough cellulose material that researchers say can be used to purify water and detect pollutants. They envision Syn-SCOBY being used in the biomedical field and for food applications.

“We foresee a future where diverse materials could be grown at home or in local production facilities, using biology rather than resource-intensive centralized manufacturing,” said associate professor Timothy Lu, of MIT’s departments of biological engineering and electrical engineering and computer science.

Read more (MIT)

- Published in Science

Fifth Time the Charm for KOMBUCHA Act?

For the fifth year in a row, the KOMBUCHA Act was reintroduced to Congress. If the legislation passes, kombucha beverages would be exempt from excise taxes intended for alcoholic beverages. The act proposes to raise the alcohol by volume (ABV) threshold for kombucha from its current level of 0.5% to 1.25%.

“The past year has been incredibly hard on businesses in Oregon and across the country, especially as supply chains have been disrupted. Still, kombucha is one the fastest growing beverage industries in the world,” says U.S. Rep. Earl Blumenauer (D-OR). “There’s no reason why kombucha brewers and sellers should get taxed like beer. Our common sense legislation would eliminate this burden and support a burgeoning industry that has a major impact on Oregon’s food and beverage economy.”

U.S. retail sales of kombucha sales grew 2.4% over the twelve months though mid-July 2020, to $703.2 million, according to SPINS.

“Modernize Taxes & Regulations”

Blumenauer first introduced the bill in 2017 — and has reintroduced it every year since. Senator Ron Wyden (D-OR), the Senate Finance Chair, is the bill’s co-sponsor.

The word “KOMBUCHA” also has a double meaning — it is an acronym for Keeping Our Manufacturers from Being Unfairly taxed while Championing Health Act. The legislators understand kombucha is a fast-growing beverage category, especially in their home state of Oregon, home to many kombucha brands.

“The growth of kombucha production in Oregon and nationwide creates jobs and a beverage folks enjoy,” Wyden said. “It’s been a particularly difficult year for small businesses, and our bill would modernize taxes and regulations so these businesses can continue to grow and sell their products in stores across the country.”

Kombucha Brewers Lobby

Commercial kombucha brewers are especially concerned with the regulation. In 2010, Whole Foods and other retailers pulled kombucha off shelves as the Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau investigated whether alcohol levels in kombucha were higher than what was printed on the label. And since then, consumers — and even other brands — have filed lawsuits against various kombucha brands, alleging alcohol levels higher than indicated.

Kombucha can keep fermenting after it’s made, as the yeasts continue to eat sugars. Under current law, if kombucha leaves a processing facility at 0.4% ABV, but increases to over 0.5% by the time it’s placed on grocery store shelves, the brewer would have to pay federal alcohol taxes like a beer brand.

Hannah Crum, co-founder and president of Kombucha Brewers International (KBI), the trade organization for kombucha brewers, emphasizes that kombucha producers fear constant repercussions from the law.

“These numbers were created over 100 years ago during prohibition,” says Crum, and notes there are no scientific studies on these ABV values. “Kombucha labels say ‘Alcohol is present’ — no one is trying to trick the consumer.”

Reads a statement from KBI: “ These laws were never intended to make kombucha subject to taxes designated for beer. Passing the KOMBUCHA Act under the next appropriations bill will relieve this unnecessary burden on kombucha brewers. Only kombucha above that level (1.25%) will be subject to federal excise taxes when this Act becomes law.”

KBI has actively lobbied for the bill’s passage. Big kombucha brands (GT’s and Health-Ade) have supported the bill actively. KBI — for the first time — is asking consumers to write to their government representatives (via a form on their website) to urge them to support the bill.

- Published in Business

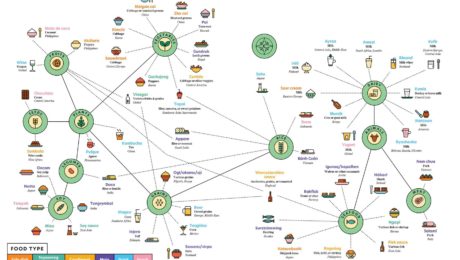

The World of Fermented Foods

In the latest issue of Popular Science, a creative infographic illustrates “the wonderful world of fermented foods on one delicious chart.” It represents “a sampling of the treats our species brines, brews, cures, and cultures around the world,” and is particularly interesting as it shows mainstream media catching on to fermentation’s renaissance. Fermentation fit with the issue’s theme of transformation in the wake of the pandemic.

Read more (Popular Science)

- Published in Food & Flavor

7 Takeaways for Cideries in 2021

Despite a year when cideries around the world were forced to close down taprooms and cancel restaurant sales due to the pandemic, cider sales grew 9% in 2020.

“I know some of you are barely hanging on — but you are hanging on,” said Michelle McGrath, executive director of the American Cider Association (ACA). “We did not waver, we held our shares and we kept growing.”

McGrath presented industry statistics at CiderCon 2021, the ACA’s annual global cider conference. Because of the ongoing coronavirus pandemic, the conference was virtual this year. Nearly 800 people from 18 countries and 41 states attended the three-day conference.

Smaller, local cider brands sparked consumer interest in 2020. Sales of regional cider brands grew 33%, while national brands declined 6%.

The impact of the pandemic, though, has been severe on certain sectors of the industry. On-premise cider sales (in restaurants, breweries and taprooms) declined nearly 70% from 2019.

“We’re resilient, we’re tough, we’re savvy. You couldn’t have predicted how your business would have stood up to a once-in-a-lifetime pandemic,” said Anna Nadasdy, director of customer success at Fintech, a data company for the alcohol industry.

Nadasdy’s keynote on expected consumer trends in 2021 cited the key drivers influencing consumer behavior — the economy, politics and natural disasters. Here are seven of her takeaways for cideries:

- Consumers Buying all Alcohol Types

Though consumers have long been loyal to one type of alcohol — beer, wine or spirits — the “beer guy or wine gal” label is disappearing. Over one-third of consumers are purchasing from all three major categories.

Hard seltzer is the third largest beer segment (16% of dollar share, behind domestic premium and imported beers), but it’s the fastest growing. This is exciting for cider makers, Nadasdy notes — hard seltzer in 2018 was the size of the cider market today.

- Fruit-Flavored Cider is Growing

Though apple cider still dominates the cider market with 52% of sales, fruit-flavored cider grew three points in the past year to 12% of sales. The top three fruit-flavored products are: Ace Pineapple Craft Cider, Incline Scout Hopped Marionberry Cider and 2 Towns Ciderhouse Pacific Pineapple Cider.

(Other products in the cider category include: mixed flavors, dry cider, seasonal cider/perry, herb/spice cider.)

- Cider is Making Waves in Craft Beer

Cider — tracked as part of the overall craft beer category — is proving a worthy participant.Cider has 11% of the dollar share, second only to the category leader, India Pale Ale (41% of the market).

“That’s really impressive for such a small base,” Nadasdy says. “Even though you guys are a smaller segment, you still have a lot to contribute to the overall beer category. And I think it’s important when you’re having these conversations with retailers that you are able to point out these wins.”

- Hard Kombucha is Gaining Ground

Cideries are competing with hard kombucha. Though hard kombucha is a fermented tea and not a cider, retailers consider hard kombucha and cider comparable drinks. And hard kombucha sales are growing quickly.

“Although small now, keep an eye on (hard) kombucha,” Nadasdy said.

- Prepare for Changed On-Premise Sales

Once wide-spread vaccination is in place and on-premise dining returns, expect fundamental changes such as more online ordering, healthier menu choices and a rise in food tech like tablet menus. The National Restaurant Association listed other significant changes that will impact cideries:

- Streamlined menus. There will be fewer menu items, with 63% of fine dining operators and half of casual and family dining operators saying they will reduce their offerings.

- Alcohol-to-go. Seven in 10 full-service restaurants added alcohol-to-go during the pandemic. Thirty-five percent of customers say they are more likely to choose a restaurant that offers alcoholic beverages to-go.

- Rosé-Flavored Cider is Out

Every brand of rosé-flavored cider is losing sales. The top three brands showing the most significant losses in this category are: Angry Orchard, Bold Rock and Virtue.

- Cans Are King

Cans are leading the dollar share of the market, growing at 1.5 times the rate of bottles. Six-pack (11-13 ounce) cans are now the top share item with 29% of total cider sales. This is followed by six-pack (11-13 ounce) bottles and 4-pack (18-ounce) cans. (These figures do remove shares of Angry Orchard, which sells in bottles. Because Angry Orchard dominates 40% of the cider market, they skew the data.)

- Published in Business, Food & Flavor

Launching a Fermented Brand

One of the biggest hurdles in the food and beverage industry is getting a product to market — an even bigger challenge for fermented food and drink brands featuring live bacteria.

“Fermented foods in general are still relatively new in the commercial marketplace. When we started, most beer distributors knew nothing about it. And that’s still a big challenge, how to communicate what you have. What is a fermented food? Why should people care about it?” says Joshua Rood, co-founder and CEO of Dr Hops Real Hard Kombucha. Rood shared his advice during a TFA webinar, Launching a Fermented Brand.

Rood officially began Dr Hops in 2015 with co-founder Tommy Weaver. They met in a yoga class, and turned their passion for health and great hops into a kombucha beer they started brewing in Rood’s kitchen.

At the time, there was a lot of variety and craft beer and kombucha, but hard kombucha was unheard of. “You don’t have a lot of focus on health in alcohol,” Rood says.

Rood went to investors with a pitch deck that outlined why traditional alcohol products don’t appeal to a health-conscious consumer — craft beer is made with gluten, cider is high in sugar and hard alcohol is too strong for regular use. Dr Hops, meanwhile, is gluten-free, low in sugar, unfiltered, made with organic ingredients and full of active probiotics.

“We have a passion for creating more delightful, health-conscious alcohol, and really pushing the envelope with that,” Rood says. “One of our biggest challenges is still how to communicate that into a very tiny amount of time to consumers, retailers and distributors.”

Starting in a category that didn’t yet exist, figuring out licensing took years. Dr Hops began with $13,000 raised from a Kickstarter campaign, then crowdsourced another $10,000 the following year. By 2017 — with labelling, alcohol licensing and product stability figured out — investors pledged $115,000, enough to start small-scale commercial production. Dr Hops officially went to market in 2018, self-distributing and selling at street fairs and beer festivals.

“Part of the key to selling stuff without a huge marketing budget is focus,” says Alex Lewin, webinar moderator, Dr Hops advisor and TFA Advisory Board member. “Dr Hops started in the Bay Area, and won over relationships we had with some retailers — we had some real advocates. Don’t do a national launch if you have no budget.”

Rood stresses education is a key piece of marketing for the fermentation category.

“How much is the whole community speaking about and educating the world about and celebrating the value of live fermented foods? The more we’re all doing that, the more it works to sell these products,” he adds.

Test audiences, consumer feedback and word-of-mouth marketing have been key to Dr Hops success.

“The fact that we were able to grow our business almost three times in 2020 even in the pandemic with no marketing is one of the best things we have to say about what we have. People want this,” Rood says.

Highlighting strengths helps Dr Hops distinguish itself in a newly-competitive field of hard kombucha brands. Dr Hops’ product line includes flavors that compare to well-known alcohol beverages. Their Kombucha Rose flavor is a substitute for wine, Ginger Lime for a cocktail, Kombucha IPA for beer and Strawberry Lemon for a mimosa.

“While people might not understand hard kombucha, they pretty much already have a preference between beer, wine, cocktail and champagne or spritzers,” Rood says.

Health is core to Dr Hops, but higher-alcohol drinks are also higher in calories. Seltzer has been a key competitor to hard kombucha because seltzer’s calories are low.

“But it’s not interesting,” Rood says. “If you really love alcohol or food or beverage in general, you want something more interesting than that. At this point, we’re willing to gamble on enough people who care about transparency and authenticity that if we put the nutrition label on there and list all the ingredients, even if it doesn’t compare very well on a calorie level, there’s enough else to it that people are going to try it.”

- Published in Business

Pandemic Spurs Fermented Beverages

The coronavirus continues to drive sales of fermented drinks. Lifeway’s kefir, Farmhouse Culture’s kraut juice, Probitat’s fermented planted-based smoothies, Flying Ember’s hard kombucha and Buoy Hydration’s fermented drinks all report increased sales as consumers take a bigger interest in the immune-enhancing benefits of fermented beverages.

“As demand ramps up for immune-enhancing products, manufacturers have an opportunity to innovate with immune-supporting ingredients and flavors,” says Becca Henrickson, marketing managed of Wixon, a flavor and seasoning company. “When flavoring beverages with immune support ingredients, selecting flavors that increase or complement a product’s health perception is optimal.”

Read more (Food Business News)

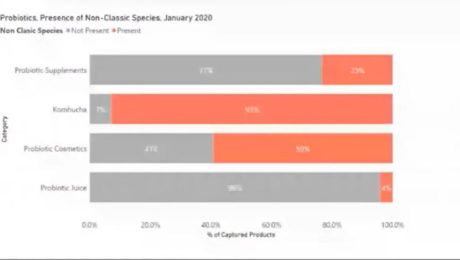

New Strains Drive Probiotic Market

Kombucha and cosmetics are driving growth in the probiotic and prebiotic markets by making products that use non-classic strains of bacteria.

The e-commerce market for probiotic supplements was estimated at $973 million across 20 countries in 2020. America accounts for almost half of those sales. Ewa Hudson, director of insights for Lumina Intelligence, shared this info at the Probiota Americas 2020 Conference. (Lumina and Probiota Americas are parts of William Reed Business Media, the parent company for FoodNavigator.com.) The session, New Horizons for Prebiotics & Probiotics, included Lumina’s insight into non-classic bacteria strains and a panel discussion with leaders in the probiotics field.

In 2020, 32% of all probiotics in America — and 41% of the best-selling ones — contained non-classic species. Hudson said this species classification is a messy space, especially from a consumer’s perspective, because there are so many species. Kombucha includes the most non-classic probiotic species — of those products with probiotics, 93% include non-classic bacteria .

Most products with probiotics include one of the four common bacteria species: lactobacilli, bifidobacterium, bacillus and saccharomyces. Lumina excluded these four from their research to focus on the growth of the non-classic probiotic strains. These include: streptococcus thermophilus, kombucha culture, lactococcus lactis, bifida ferment lysate, enterococcus faecium, streptococcus salivarius, clostridium butyricum and streptococcus faecalis.

Though probiotics are often used in supplements, more fermented food and beverage manufacturers are using probiotic strains in their products, especially in the growing alternative protein market.

Synbiotics are also becoming more widely used; the study found synbiotics were the most prevalent formulate in probiotics. Synbiotics are a combination of both prebiotics and postbiotics. A synbiotic ensures that probiotics will have a food source in the gut.

(Probiotics are live microorganisms, friendly bacteria that provide health benefits. Probiotics can be found in fermented food and taken as supplements. Prebiotics are dietary fibers that feed the probiotics. Postbiotics are an emerging concept in the “biotics” space — postbiotics are the waste byproduct of probiotics.)

“With probiotics, we are really only starting to scratch the surface with the development of synbiotics,” says Jens Walter, PhD, professor of ecology, food and the microbiome at APC Microbiome Ireland.

The new generation of probiotics will depend on strains that are “efficacious in the gut,” Walter noted.

“If you look into the probiotic market, most of the lactobacillus species — and also species like bifidobacterium lactis — are not inherent organisms of the human gut. We’re using a lot of organisms that I would argue have an ecological disadvantage in the gut,” Walter says. “If you’re talking about next generation probiotics, I think what will become is we are looking for the key players in the gut, specifically key players that are underrepresented or linked to certain benefits, and then we are trying to put them back in the ecosystem.”

It’s challenging to find a prebiotic or postbiotic that is precise, he continues.

“Every human has a distinct microbiome. So it’s likely a synbiotic designed for one human may not be as functional in another human,” Walter says. “The opportunities here are tremendous.”

Daniel Ramon Vidal, vice president of research and development and health and wellness at the American food processing company Archer-Daniels-Midland (ADM), also spoke. He noted that the human body is made up of trillions of microbial cells, but we know little about these microbial worlds.

“There is an enormous amount of possibilities to isolate new strains that are living in our body,” Daniels says. “We need as much science as possible, that’s my message”

The panel agreed that postbiotics has become one of the next great concepts that scientists, manufacturers and gastroenterologists have latched onto. But consumers are not as familiar with postbiotics as they are with probiotics and prebiotics , notes Justin Green, PhD, director of scientific affairs for EpiCor, a postbiotic ingredient produced by Cargill.

“This causes more confusion, so I think that’s going to be another interesting aspect of postbiotics — both the identity of what postbiotics are and how it confers its benefits and (how that will be) communicated to the consumer,” Green says.

Retail Sales Trends for Fermented Food and Beverage

Kimchi, fermented sauces and tempeh are driving growth in the fermented food and beverage category, a $9.2 billion industry that’s grown 4% in the last year.

“We’re excited about the growth potential for fermented food. While fermented food represents about 1.4% of the market today, there are segments that are tracking well above the growth of food and beverage [overall] that are poised for disruption in the future,” says Perteet Spencer, vice president of strategic solutions at SPINS. Spencer shared this information in a recent webinar hosted by The Fermentation Association. “There’s a ton of opportunity to scale and increase the footprint of these products.”

SPINS spent weeks working with TFA to define the fermentation industry’s sales, drilling into 10 fermented product categories and 57 product types. Wine, beer and cheese sales were excluded from the data — those categories are very large, and would obscure trends in smaller categories. (All three are also well-represented by other organizations.)

Pickles and fermented vegetables “is a space that’s seen [a] pretty explosive uptick in growth over the past year,” Spencer says. Every segment is growing — kimchi, sauerkraut, beets, carrots, green beans, sliced and speared pickles and all other vegetables — with pickles the largest, nearly 60% of the category.

The biggest growth, though, is coming from products other than pickled cucumbers. Kimchi is at the center of numerous consumer retail trends. Consumers are purchasing healthier food made with fewer ingredients, and they want food with international flavors. Kimchi makes up only 7% of the category, but sales are increasing at an explosive 90% growth rate.

More people are experimenting with fermenting while they’re at home during the coronavirus pandemic, but these kitchen DIYers do not appear to be detracting from sales.

“The more people make fermented foods, they appreciate what’s available in the store that maybe didn’t exist five or 10 years ago,” notes Alex Lewin, author and TFA advisory board member who moderated the webinar. “Anyone who has made kimchi knows it takes a lot, it makes a big mess, you get red pepper powder stuck under your fingernails and onion in your eyes. I can make kimchi (at home), and then once I’ve made kimchi, I’m like ‘Ok, maybe next time I’ll buy it.’”

Fermented sauces are also growing, up 24% in 2020. The largest segment in sauces is, of course, soy sauce, almost 85% of the category. But gochujang, less than 2% of the category, is increasing at over a 56% growth rate.

Versatility is helping sauces, pickles and fermented vegetables, Spencer says. Any food product with multiple uses is selling well. The condiments and sauces can be used as a topping on eggs, hamburgers or pizza, or mixed-in a salad, rice dish or soup.

Sake, plant-based meat alternatives and miso had combined annual growth of $75 million in 2020. Sake grew 16%, and both plant-based meat alternatives and miso each grew 26%.

Yogurt and kombucha still dominate the fermented food and beverage market. Yogurt is 81% of the market; if yogurt is removed, kombucha is 51% of the remainder.. Both have experienced slowdowns in sales from their peaks. Kombucha sales have slowed recently, as grab-n-go opportunities have shrunk during the pandemic.

Yogurt giant brands Chobani, Yoplait and Dannon still dominate the category, as do GT Kombucha, Health-Ade and Kevita reign for kombucha.

Spencer notes the 4% growth rate of fermented products overall would be higher without yogurt. It’s a large category that — despite an uptick in 2020 during the pandemic – has been fairly flat in recent years. Core (traditional) yogurt has been growing at a 1.6% rate; Greek yogurt, at about twice that pace. Those two segments account for roughly 80% of the category.

“This is an opportunity for disruption for emerging brands,” Spencer says. “We’re already seeing some of the legacy segments start to get disrupted by new innovation, so I’m excited to see the evolution of that innovation and where that goes and kind of what opportunities peek out of that.”

“Overall, we’re seeing historically small segments gaining traction in the marketplace,” Spencer adds. “The pandemic has brought a renewed consumer focus on the fermented space.”

Though fermented products have an added healthy benefit, customers are looking for delicious flavor first.

“In these fermented categories we covered today, taste first is always really important. I think people are going to these categories for different taste experiences,” Spencer says. “If you can level up with a functional benefit, that’s fantastic, but we have to balance the taste first. If it’s highly functional but doesn’t taste good, it just doesn’t have the same success.”

- Published in Business