SCOBY as Water Filter?

Can you use bacteria to eliminate bacteria? Commercial water filters remove contaminants from water, but the pores eventually clog, causing water to filter more slowly. Now researchers are studying a living membrane to filter water: a kombucha SCOBY.

Researchers at Montana Technological University (MTU) and Arizona State University (ASU) found the films of cellulose that make up a SCOBY are 19-40% more effective than commercial filtration systems at preventing the formation of bacterial biofilms. The SCOBY filter also maintained a fast rate of filtration for a longer period of time. Though a biofilm did eventually form on top of the SCOBY, it contained fewer bacteria than in a commercial filter.

“The scientists couldn’t use the wild yeasts typically used in kombucha because the yeasts are difficult to modify genetically,” reads an article in Wired. “Instead, the researchers used lab-grown yeast, specifically a strain called Saccharomyces cerevisiae, or brewer’s yeast. They combined the brewer’s yeast with a bacteria called Komagataeibacter rhaeticus (which can create a lot of cellulose) to create their ‘mother’ SCOBY.”

Researchers engineered the cells in the yeast to produce glow-in-the-dark enzymes, which sense pollutants and break them down. SCOBY-based filters are not only inexpensive to make, they biodegrade when discarded.

Their research was published in the American Chemical Society journal ACS ES&T Water.

Read more (Wired)

Tastier Apple Spirits

Thanks to their high sugar content and strong flavor, apples have been a great base for spirits like cider, calvados and applejack for hundreds of years. But “many decisions about their processing are still subjectively determined.” When to stop distillation for the most flavorful liquor, for example, is open to question. But new research has identified the best conditions for making apple-based spirits with the most desirable qualities and taste.

Researchers with the American Chemical Society fermented apples into a mash, then distilled it in a German-style batch column. Heat concentrates the alcohol and “removes unpleasant fermentation byproducts, such as carboxylic acids that can impart unclean, rancid, cheesy and sweaty flavors.” The researcher’s mash was continuously monitored during heating, and the levels of the nine carboxylic acids measured.

Heating the mash too quickly yielded unwanted flavor compounds and a bland aroma. But raising the temperature of the cooling tower slightly produced a good fragrance intensity, and reduced carboxylic acid levels.

Read more (American Chemical Society)

- Published in Food & Flavor, Science

Yogurt Alters Gut Microbiome

It’s widely appreciated that consuming high-quality yogurt can aid a healthy diet. Now new research shows eating yogurt changes the composition of the human gut microbiome.

In a new human study published in BMC Microbiology, researchers studied the microbiome of European twins. Results found those regularly eating yogurt had less visceral fat mass, reduced insulin levels and an increase of bacterial species in the gut. Strains S. thermophilus, B. animalis subsp. lactis., S. thermophilus and B. animalis subsp. lactis were all present in yogurt eaters.

The study also found the yogurt bacteria are “transient members of the gut microbiome and do not durably engraft within the gut lumen.”

Read more (BMC Microbiology)

Fermentation Key to Mass Producing Anti-Cancer Compounds

Thyme and oregano possess an anti-cancer compound that suppresses tumor development, but adding more to your tomato sauce isn’t enough to gain significant benefit. The key to unlocking the power of these plants is in amplifying the amount of the compound created or synthesizing the compound for drug development.

And exciting for the field of fermentation: extracting those beneficial compounds from the plant is done through fermentation.

“The fermentation process is so important to food and beverage, pharmaceutical and biofuels production that Purdue now offers a fermentation science major,” reads a press release from Purdue University.

Researchers at Purdue took the first step in using the compound in pharmaceuticals by mapping its biosynthetic pathway, a sort of molecular recipe of the ingredients and steps needed.

“These plants contain important compounds, but the amount is very low and extraction won’t be enough,” said Natalia Dudareva, distinguished professor of biochemistry in Purdue’s College of Agriculture and director of Purdue’s Center for Plant Biology, who co-led the project. “By understanding how these compounds are formed, we open a path to engineering plants with higher levels of them or to synthesizing the compounds in microorganisms for medical use. “It is an amazing time for plant science right now. We have tools that are faster, cheaper and provide much more insight. It is like looking inside the cell; it is almost unbelievable.”

Thymol, carvacrol and thymohydroquinone are flavor compounds in thyme, oregano and other plants in the Lamiaceae family. They have antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant and other properties beneficial to human health. Thymohydroquinone has been shown to have anti-cancer properties and is particularly of interest, said Dudareva..

In collaboration with scientists from Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg in Germany and Michigan State University, the Purdue team uncovered the entire biosynthetic pathway to thymohydroquinone, including the formation of its precursors thymol and carvacrol, and the short-lived intermediate compounds along the way.

The findings alter previous views of the formation of this class of compounds, called phenolic or aromatic monoterpenes, for which only a few biosynthetic pathways have been discovered in other plants, she said. The study results were published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“These findings provide new targets for engineering high-value compounds in plants and other organisms,” said Pan Liao, co-first author of the paper and a postdoctoral researcher in Dudareva’s lab. “Not only do many plants contain medicinal properties, but the compounds within them are used as food additives and for perfumes, cosmetics and other products.”

Now that this pathway is known, plant scientists could develop cultivars that produce more of the beneficial compounds, or it could be incorporated — using fermentation — into microorganisms like yeast for production.

A $5 million grant from the National Science Foundation supported the research. Using RNA sequencing and correlation analysis, the team screened more than 80,000 genes from plant tissue samples and identified the genes needed for thymohydroquinone production. Based on what was known about the compound structure and through metabolite profiling and biochemical testing, the team identified the biosynthetic pathway.

“The intermediate formed in the pathway was not what had been predicted,” Liao said. “We found that the aromatic backbone of both thymol and carvacrol is formed from γ-terpinene by a P450 monooxygenase in combination with a dehydrogenase via two unstable intermediates, but not p-cymene, as was proposed.”

More pathways are now being discovered, thanks to the availability of RNA sequencing to perform high-throughput gene expression analysis, according to Dudareva.

“We, as scientists, are always comparing pathways in different systems and plants,” Dudareva said. “We are always in pursuit of new possibilities. The more we learn, the more we are able to recognize the similarities and differences that could be key to the next breakthrough.”

- Published in Science

“Our Customers Do Not Even Know What is a Fermented Item”

Fermentation is cloaked in mystery for many — it’s bubbly, slimy, stinky and not always Instagram-ready. In The Fermentation Association’s recent member survey, this lack of

understanding of fermentation and its flavor and health attributes among consumers was cited by 70% of producers as a major obstacle to increased sales and acceptance of fermented products.

“We get so many questions from our readers about fermentation. People are very interested, but have very, very little knowledge about it,” says Anahad O’Connor, reporter for The New York Times. O’Connor has written about fermented foods multiple times in the last few months, and those articles were among The Times’ most emailed pieces of 2021. “I think there’s a huge opportunity to educate consumers about fermented foods, their impact on the gut and health in general.”

O’Connor spoke on consumer education as part of a panel of experts during TFA’s conference, FERMENTATION 2021. Panelists — who included a producer, retailer, scientist, educator and journalist — agreed consumer education is lacking. But the methods of how to fill that gap are contested.

How to Tell Consumers “What is a Fermented Food?”

There are differences between what is a fermented product and what is not — a salt brine vs. vinegar brine pickle, or a kombucha made with a SCOBY or one from a juice concentrate, for example.

“I can tell you that the majority of our customers do not even know [what is a] fermented item,” says Emilio Mignucci, vice president of Philadelphia gourmet store Di Bruno Bros., which specializes in cheese and charcuterie. When customers sample products at the store, they can easily taste the differences between a fermented and a non-fermented product, Mignucci says. But he feels the health benefits behind that fermented product are not the retailer’s responsibility to communicate. “I need you guys [producers] to help me deliver the message.”

“Retailers like myself, buyers, we want to learn more to be able to champion [fermented foods] because, let’s face it, fermented foods is a category that’s getting better and better for us as retailers and we want to speak like subject matter experts and help our guests understand.”

Now — when fermentation tops food lists and gut health is mainstream — is the time for education.

“This microbiome world that we’re in right now is sort of a really opportune moment to really help the public understand what fermented foods are beyond health,” says Maria Marco, PhD, professor of food science at the University of California, Davis (and a TFA Advisory Board Member).

Kombucha Brewers International (KBI) created a Code of Practice to address confusion over what is or is not a kombucha. KBI is taking the approach that all kombucha is good, pasteurized or not, because it’s moving consumers away from sugar- and additive-filled sodas and energy drinks.

“That said, consumers deserve the right to know why is this kombucha at room temperature and this kombucha is in the fridge and why does this kombucha have a weird, gooey SCOBY in it and this one is completely clear,” says Hannah Crum, president of KBI. “They start to get confused when everything just says the word ‘kombucha’ on it.”

KBI encourages brewers to be transparent with consumers. Put on the label how the kombucha is made, then let consumers decide what brand they want to buy.

Should Fermented Products Make Health Claims?

Drew Anderson, co-founder and CEO of producer Cleveland Kitchen (and also on TFA’s Advisory Board), says when they were first designing their packaging in 2013, they were advised against using the term “crafted fermentation” on their label because it would remind consumers of beer or wine. But nowadays, data shows 50% of consumers associate the term fermentation with health.

“In the last five to six years, it’s changed dramatically and people are associating fermentation as being good for them, which is good for my products,” he says.

Cleveland Kitchen, though, does not make health claims on their fermented sauerkraut, kimchi and dressings. Anderson says, as a small startup, they don’t have the resources to fund their own research. They instead attract customers with bold taste and striking packaging.

“We’re extremely cautious on what we say on the package because we don’t have an army of lawyers like Kevita (Pepsi’s Kombucha brand), we don’t have the Pepsi legal team backing us here,” Anderson says. Cleveland Kitchen submits new packaging designs in advance to regulators, to make sure they’re legally acceptable before rolling them out.

O’Connor says taste is the No. 1 driver for consumers. This is why healthful but sticky and stinky natto (fermented soybeans) is not a popular dish in America, but widely consumed in Japan.

“Many American consumers, unfortunately, aren’t going to gravitate toward that, despite the health benefits,” he says.

Crum disagrees. “Health comes first,” she says. As more and more kombucha brands emphasize lifestyle, and don’t even advertise their health benefits, she feels they are doing a disservice to the consumer. “Why pay that much money for kombucha if you don’t know it’s good for you too?”

- Published in Business, Food & Flavor, Health, Science

The Rise of Fermented Foods and -Biotics

Microbes on our bodies outnumber our human cells. Can we improve our health using microbes?

“(Humans) are minuscule compared to the genetic content of our microbiomes,” says Maria Marco, PhD, professor of food science at the University of California, Davis (and a TFA Advisory Board Member). “We now have a much better handle that microbes are good for us.”

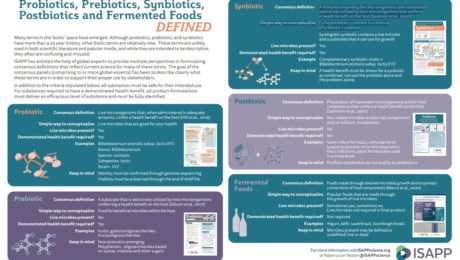

Marco was a featured speaker at an Institute for the Advancement of Food and Nutrition Sciences (IAFNS) webinar, “What’s What?! Probiotics, Postbiotics, Prebiotics, Synbiotics and Fermented Foods.” Also speaking was Karen Scott, PhD, professor at University of Aberdeen, Scotland, and co-director of the university’s Centre for Bacteria in Health and Disease.

While probiotic-containing foods and supplements have been around for decades – or, in the case of fermented foods, tens of thousands of years – they have become more common recently . But “as the terms relevant to this space proliferate, so does confusion,” states IAFNS.

Using definitions created by the International Scientific Association for Postbiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP), Marco and Scott presented the attributes of fermented foods, probiotics, prebiotics, synbiotics and postbiotics.

The majority of microbes in the human body are in the digestive tract, Marco notes: “We have frankly very few ways we can direct them towards what we need for sustaining our health and well being.” Humans can’t control age or genetics and have little impact over environmental factors.

What we can control, though, are the kinds of foods, beverages and supplements we consume.

Fermented Foods

It’s estimated that one third of the human diet globally is made up of fermented foods. But this is a diverse category that shares one common element: “Fermented foods are made by microbes,” Marco adds. “You can’t have a fermented food without a microbe.”

This distinction separates true fermented foods from those that look fermented but don’t have microbes involved. Quick pickles or cucumbers soaked in a vinegar brine, for example, are not fermented. And there are fermented foods that originally contained live microbes, but where those microbes are killed during production — in sourdough bread, shelf-stable pickles and veggies, sausage, soy sauce, vinegar, wine, most beers, coffee and chocolate. Fermented foods that contain live, viable microbes include yogurt, kefir, most cheeses, natto, tempeh, kimchi, dry fermented sausages, most kombuchas and some beers.

“There’s confusion among scientists and the public about what is a fermented food,” Marco says.

Fermented foods provide health benefits by transforming food ingredients, synthesizing nutrients and providing live microbes.There is some evidence they aid digestive health (kefir, sourdough), improve mood and behavior (wine, beer, coffee), reduce inflammatory bowel syndrome (sauerkraut, sourdough), aid weight loss and fight obesity (yogurt, kimchi), and enhance immunity (kimchi, yogurt), bone health (yogurt, kefir, natto) and the cardiovascular system (yogurt, cheese, coffee, wine, beer, vinegar). But there are only a few studies on humans that have examined these topics. More studies of fermented foods are needed to document and prove these benefits.

Probiotics

Probiotics, on the other hand, have clinical evidence documenting their health benefits. “We know probiotics improve human health,” Marco says.

The concept of probiotics dates back to the early 20th century, but the word “probiotic” has now become a household term. Most scientific studies involving probiotics look at their benefit to the digestive tract, but new research is examining their impact on the respiratory system and in aiding vaginal health.

Probiotics are different from fermented foods because they are defined at the strain level and their genomic sequence is known, Marco adds. Probiotics should be alive at the time of consumption in order to provide a health benefit.

Postbiotics

Postbiotics are dead microorganisms. It is a relatively new term — also referred to as parabiotics, non-viable probiotics, heat-killed probiotics and tyndallized probiotics — and there’s emerging research around the health benefits of consuming these inanimate cells.

“I think we’ll be seeing a lot more attention to this concept as we begin to understand how probiotics work and gut microbiomes work and the specific compounds needed to modulate our health,” according to Marco.

Prebiotics

Prebiotics are, according to ISAPP, “A substrate selectively utilized by host microorganisms conferring a health benefit on the host.”

“It basically means a food source for microorganisms that live in or on a source,” Scott says. “But any candidate for a prebiotic must confer a health benefit.”

Prebiotics are not processed in the small intestine. They reach the large intestine undigested, where they serve as nutrients for beneficial microorganisms in our gut microbiome.

Synbiotics

Synbiotics are mixtures of probiotics and prebiotics and stimulate a host’s resident bacteria. They are composed of live microorganisms and substrates that demonstrate a health benefit when combined.

Scott notes that, in human trials with probiotics, none of the currently recognized probiotic species (like lactobacilli and bifidobacteria) appear in fecal samples existing probiotics.

“There must be something missing in what we’re doing in this field,” she says. “We need new probiotics. I’m not saying existing probiotics don’t work or we shouldn’t use them. But I think that now that we have the potential to develop new probiotics, they might be even better than what we have now.”

She sees great potential in this new class of -biotics.

Both Scott and Marco encouraged nutritionists to work with clients on first improving their diets before adding supplements. The -biotics stimulate what’s in the gut, so a diverse diet is the best starting point.

Definition & History of Fermentation

“Human civilization simply would not have been possible without fermented foods and beverages…we’re here today because fermented foods have been popular for humans for at least 10,000 years,” says Bob Hutkins, professor of food science at the University of Nebraska (and a recent addition to TFA’s Advisory Board).

Hutkins was the opening keynote speaker at FERMENTATION 2021, The Fermentation Association’s first international conference. His presentation explored the history, definition and health benefits of fermented foods.

Cultured History

The topic of fermentation extends to evolution, archaeology, science and even the larger food industry.

“The discipline of microbiology began with fermentation, all the early microbiologists studied fermentation,” Hutkins says.

Louis Pasteur patented his eponymous process, developed to improve the quality of wine at Napoleon III’s request. The microbes studied back then — lactococcus, lactobacillus and saccharomyces — remain the most studied strains.

“What interested those early microbiologists — namely how to improve food and beverage fermentation, how to improve their productivity, their nutrition — are the very same things that interest 21st century fermentation scientists,” Hutkins says.

Hutkins is the author of one of the books considered gospel in the industry, “Microbiology and Technology of Fermented Foods.” He says that fermented foods defined the food industry. In its early days, it was small-scale, traditional food production that “we call a craft industry now.” At the time, food safety wasn’t recognized as a microbiological problem.

Today’s modern food industry manufactures on a large-scale in high throughput factories withmany automated processes. Food safety is a priority and highly regulated. And, thanks to developments in gene sequencing, many fermented products are made with starter cultures selected for their individual traits.

“But I would say that there’s been kind of a merging between these traditional and modern approaches to manufacturing fermented foods, where we’re all concerned about time sensitivity, excluding contaminants, making sure that we have consistent quality, safety is a vital concern and extensive culture knowledge,” Hutkins says.

Defining & Demystifying

Fermentation — “the original shelf-life foods” — is experiencing a major moment. “Fermented foods in 2021 check all the topics” of popular food genres: artisanal, local, organic, natural, healthy, flavorful, sustainable, entrepreneurial, innovative, hip and holistic. “They continue to be one of the most popular food categories,” Hutkins continues.

Interest in fermentation is reaching beyond scientists, to nutritionists and clinicians. But Hutkins says he’s still surprised to learn how many professionals don’t understand fermentation. To address the confusion, a panel of interdisciplinary scientists created a global definition of fermented foods in March 2021.

“Fermentation was defined with these kind of geeky terms that I don’t know that they mean very much to anybody,” he says.

The textbook biochemical definition of fermentation that a microbiologist learns in Biochemistry 101 doesn’t work for a nutritionist or clinician focusing on fermentation’s health benefits. The panel, which spent a year coming to a consensus, wanted a definition that would simply illustrate “raw food being converted by microbes into a fermented food.” The new definition, published in the the journal Nature and released in conjunction with the International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP), reads: “Foods made through desired microbial growth and enzymatic conversions of food components.”

Fermentation in 2022

Hutkins predicts 2022 will see more studies addressing whether there are clinical health benefits from eating fermented foods. The groundbreaking study on fermented foods at Stanford was important. It found that a diet high in fermented foods increases microbiome diversity, lowers inflammation, and improves immune response. But research like this is expensive, so randomized control trials are few.

Fermented foods could also make their way into dietary guidelines.

“Fermented foods, including those that contain live microbes, should be included as part of a healthy diet,” Hutkins says.

- Published in Food & Flavor, Science

The Dodo of Gastronomic History

Scientists are working to recreate an ancient garum, considered the “dodo of gastronomic history.” Beloved by Mediterranean civilizations, the fish sauce was thought by historians to be extinct, lost along with the Roman Empire.

Food technicians got new insight into this garum when archaeologists discovered sealed dolia (large clay storage vessels) at what is believed to be a former Garum Shop at Pompeii. The eruption of Mount Vesuvius buried the building, preserving the factory. The charred, powdered remains left in the vessels — plus a fish sauce recipe believed to have been from the 3rd century A.D. — has aided food techs in recreating the ancient garum.

This product uses heavily salted small fish fermented for one week with dill, coriander, fennel and other dried herbs in a closed vessel. The resulting “Flor de Garum” is sold in Spain by the Matiz brand in amphora-shaped glass bottles.

Top chefs in Spain have been using Flor de Garum in new dishes. Mario Jiménez Córdoba, chef at El Faro in Cádiz, uses it in black-truffle ice cream, a raw sea bass dish and chocolate ganache.

“When people think of garum,” Jiménez says, “they imagine something that smells disgusting. But we have to think of garum like we would salt, or soy sauce. You use only a few drops, and the flavor is incredible.”

Read more (Smithsonian Magazine)

- Published in Food & Flavor, Science

Infant “Alt-Formula”

By using precision fermentation, food technology company Helaina is manufacturing proteins nearly identical to those in human breast milk.. And they’ve raised $20 million in their first round of funding.

“We’ve seen a lot of innovation and advancement in the alternative meat and dairy space; however, the infant formula category has been stagnant for decades. I’m proud to be part of the team bringing a new solution to parents that empowers and equips them with more choice in their infant’s nutrition,” said Laura Katz (pictured). Katz, who also teaches food science at New York University, founded Helaina in 2019.

According to a press release: “To-date, precision fermentation has been used to manufacture proteins which enhance foods’ sensory profiles. Helaina is looking beyond sensory properties by leveraging their proprietary fermentation platform to unlock a suite of functional proteins that are clinically proven to boost immunity.”

Helaina bills itself as the “first company to bring human proteins to food,” but they’re not the only one using similar technology for infant formula.ByHeart and Biomilq are developing products that mimic the proteins in breast milk.

Read more (PR Newswire)

Fermentation in Anthropology

Fermented foods have had an impact on human evolution, and they continue to affect social dynamics, according to a new collection of 16 studies in the journal Current Anthropology. This research explores how “microbes are the unseen and often overlooked figures that have profoundly shaped human culture and influenced the course of human history.”

The journal’s special edition, Cultures of Fermentation, features work from multiple disciplines: microbiology, cultural anthropology, archaeology and biological anthropology. Researchers were based all over the globe.

“Humans have a deep and complex relationship with microbes, but until recently this history has remained largely inaccessible and mostly ignored within anthropology,” reads the introduction, Cultures of Fermentation: Living with Microbes. “Fermentation is at the core of food traditions around the world, and the study of fermentation crosscuts the social and natural sciences.”

The impetus for the articles was a 2019 symposium organized by the non-profit Wenner-Gren Foundation. This organization aims to bring together scholars to debate and discuss topics in anthropology.

“Fermentation is at the core of food traditions around the world, and the study of fermentation crosscuts the social and natural sciences,” the introduction continues. The aim of the symposium and corresponding research was to “foster interdisciplinary conversations integral to understanding human-microbial cultures. By bridging the fields of archaeology, cultural anthropology, biological anthropology, microbiology, and ecology, this symposium will cultivate an anthropology of fermentation.”

Here is a listing the included studies:

- Predigestion as an Evolutionary Impetus for Human Use of Fermented Food (Katherine R. Amato,Elizabeth K. Mallott, Paula D’Almeida Maia, and Maria Luisa Savo Sardaro). Using research on nonhuman primates, researchers conclude that “fermentation played a central role in enabling our earliest ancestors to survive in the forested grasslands in Africa where key anatomical features of our species emerged. Fermentation occurs spontaneously in nature. Most nonhuman primates cannot metabolize fermented products, but humans evolved the capacity to use them as fuel. …By breaking down tough and toxic plant species, fermentation helped humans meet the caloric requirements associated with their growing brains and shrinking guts. These anatomical changes both stemmed from and fueled the emergence of collective forms of know-how — microbial and human cultures fed on one another, in this view of the human past.”

- Toward a Global Ecology of Fermented Foods (Robert R. Dunn, John Wilson, Lauren M. Nichols, and Michael C. Gavin). This ecological view of fermentation maps the “emergence and divergence of the world’s many varieties of fermented foods.”

- Prehistoric Fermentation, Delayed-Return Economies, and the Adoption of Pottery Technology (Oliver E. Craig). Craig explores the central role of pottery in “people’s ability to amass the kinds of surpluses that allowed human communities to lay down roots.” Pots were ideal as the storage vessels that made it possible to domesticate microbes.

- Seeking Prehistoric Fermented Food in Japan and Korea (Shinya Shoda). This study focuses on fermentation’s rise in prehistoric Japan and Korea along with each country’s respective cultural achievements.

- Cultured Milk: Fermented Dairy Foods along the Southwest Asian–European Neolithic Trajectory (Eva Rosenstock, Julia Ebert, and Alisa Scheibner). Using archaeological evidence of fermentation, researchers track the “emergence of lactase persistence in sites where dairying made an early appearance. It appears that people ate cheese and yoghurt well before they drank milk: only a small subsection of the human population retains the enzymes needed to digest lactose into adulthood.”

- Missing Microbes and Other Gendered Microbiopolitics in Bovine Fermentation (Megan Tracy). Industrial dairy farms are finding “missing microbes” in cows, Tracy highlights in her study. Newborn calves are separated from their mothers in industrialized dairy farms, and thereby lose the critical gut connections that would have been made by drinking breast milk.

- Living Machines Go Wild: Policing the Imaginative Horizons of Synthetic Biology (Eben Kirksey). Kirksey profiles the International Genetically Engineered Machine competition in Boston, where living creatures made through genetic engineering tools are regarded as machines. “…life is being remade in novel and surprising ways as iGEM students use increasingly fast and cheap genetic engineering tools.”

- From Immunity to Collaboration: Microbes, Waste, and Antitoxic Politics (Amy Zhang). Research details “urban waste activists in China who are practicing a quiet form of resistance to the policies of the authoritarian state by using the fermentation of eco-enzymes to heal sickened rivers, bodies, and soils.”

- The Nectar of Life: Fermentation, Soil Health, and Bionativism in Indian Natural Farming (Daniel Münster). Münster delves into agricultural politics in India. He concludes that “fermentation’s effects are unpredictable: there is always more than one story to tell.”

- Microbial Antagonism in the Trentino Alps: Negotiating Spacetimes and Ownership through the Production of Raw Milk Cheese in Alpine High Mountain Summer Pastures (Roberta Raffaetà). Raffaetà investigates cheesemaking in the Italian alps, contrasting three different approaches — farmers who don’t use contemporary cheesemaking methods and only use microbes found in their terroir, , industrialized cheese producers,; and high-mountain farmers who mix cheesemaking elements from different times, such as using a standardized starter with local cultures.

- Protecting Perishable Values: Timescapes of Moving Fermented Foods across Oceans and International Borders (Heather Paxson). Raw milk cheese, cured meats and assorted ferments get their flavor from microbes. Paxson documents how transportation and distribution can erode the microbial content of these products, especially international imports. She concludes supply chains (especially international) should be further explored to make transporting products with live microbes viable.

- Enduring Cycles: Documenting Dairying in Mongolia and the Alps (Björn Reichhardt, Zoljargal Enkh-Amgalan,Christina Warinner, and Matthäus Rest). This research details the Dairy Cultures Ethnographic Database, an open resource featuring photos and videos of dairy production, landscapes and livestock in the Alps. Interviews, oral histories and folk songs are also included.

- Preserving the Microbial Commons: Intersections of Ancient DNA, Cheese Making, and Bioprospecting (Matthäus Rest). Rest traces the history and spread of dairying in Mongolia, Europe and the Near East. She concludes by calling on scientists and local producers to protect the “microbial commons” from “patenting and commodification.”

- Taste-Shaping-Natures: Making Novel Miso with Charismatic Microbes and New Nordic Fermenters in Copenhagen (Joshua Evans and Jamie Lorimer). This research for this paper took place at Noma in Copenhagen, and studied how fermentation allows the restaurant to tread a fine line “between ecologically responsible localism and the nativism associated with the rise of Denmark’s anti-immigrant right. Noma’s chefs have hit upon kōji, Japan’s “national fungus,” which they turn loose on Danish ingredients.”

- Bamboo Shoot in Our Blood: Fermenting Flavors and Identities in Northeast India (Dolly Kikon). Kikon explores fermented bamboo, a delicacy in India, and how it’s part of the local the community.

- Fermentation in Post-antibiotic Worlds: Tuning In to Sourdough Workshops in Finland (Salla Sariola). Sariola describes fermentation “as a politically progressive form of performance art.” She documents activities in China, where fermentation is used to “challenge the modernist regimes of purification that have turned microbes into the enemy. To learn to live better with microbes is to learn to live better with other kinds of difference — those associated with ethnicity, race, national origins, sexual orientation, ability, and age.”

- Published in Science