Cleveland Kitchen Acquires Sonoma Brinery

One of the under-the-radar stories from the recent Expo West was another acquisition in the fermented foods space, coming on the heels of the Bubbies and Wildbrine purchases. Ohio’s Cleveland Kitchen, producers of sauerkraut, kimchi, salad dressings and pickles, bought Healdsburg,Calif.-based Sonoma Brinery (makers with a similar line-up of pickles, kraut and pickled vegetables). No public announcement has been made, but executives from both companies confirmed the transaction to TFA. Sonoma Brinery founder/owner David Ehreth is expected to remain with the company. [Note – both Ehreth and Cleveland Kitchen’s Drew Anderson have been TFA Advisory Board members since the organization’s inception.]

- Published in Business

Q&A with Local Culture

In a food industry where greenwashing is common, Local Culture Live Ferments doesn’t pad their sales sheets with faux environmental fluff. Sustainability is core to their business practices.

“I never want to stray away from the connections with our farmers. I never want to stray away from the quality of our ferments,” says Chris Frost-McKee, director of operations for the Northern California-based vegetable fermenter. Sauerkraut is their top seller. “We take a lot of pride from the fact that we don’t ferment in plastic. We are doing our part to be as plastic-free as possible and leave the smallest footprint that we can.”

The company began as a passion project of Chris’ sister, Sarah. She recruited her brother, a home fermenter since his early 20s, and they envisioned creating two Local Culture fermentation hubs on the west coast — one where Sarah lives, in Bend, Ore., and a second in Grass Valley, Calif., Chris’ home. True to their name, they wanted to ferment with local produce. But, with the colder climate in Central Oregon cutting Bend’s growing season short, this proved impossible.

“In Grass Valley, we’re able to source cabbage eight miles from our facility, eight months out of the year. We’ve created partnerships where every year the farm is planting more and more acreage for us, rotating their cover crops. It’s a beautiful thing, it’s real regenerative farming,” Chris says. And Sarah is now creating a separate project, fermented salad dressings, under the Super Belly Ferments brand.

Local Culture started as a farmers market side hustle, but Chris and his business partners (wife Cristina and friend Elissa Wolf Blank, pictured with Chris) dove into scaling the business in 2020. They’re now in over 100 grocers in the west, including Whole Foods. Though sales boomed during the pandemic, 2022 is shaping to be their biggest year. At the recent Expo West, Local Culture was one of 40 brands selected by food distributor KeHe for the exclusive “Golden Ticket” at their TrendFinder Event This designation fast-tracks small businesses into KeHe’s product portfolio, giving them exposure to over 30,000 retail locations.

Below is a Q&A with Chris Frost-McKee, who spoke with The Fermentation Association on the Expo West show floor.

TFA: Congrats on the KeHe “Golden Ticket” win! What are you going to have to change about scaling?

Chris Frost-McKee: The tricky thing with scaling the way that we do, our fermenters are stainless steel, variable capacity fermenters. We currently have 66 of them. We’ll need to get more as we scale, but they’re only sold once a year during wine making season. They ship them over from Italy. So that presents difficulties for sure. Producing in the same size fermenters, that’s part of the integrity we’re going to keep, that’s very important to me. We ferment for a minimum of 4-6 weeks in a very regulated, temperature-controlled environment. That really helps with the consistency of our product.

We are also keeping the values the same with our farmers, making sure they can scale while staying sustainable. We’re scaling up our acreage with our main farmer next year. They rotate three successions of a summer variety of cabbage for us and then one succession of winter storage. And with those four successions, we can work about eight months directly with them, never going into cold storage.

You just returned from a planning meeting with the local farm that supplies your cabbage. Tell me more about the farmers you work with.

CFM: We’re trying to only work farmer direct. One of our closest connections is the farm Super Tuber. They are Nevada City-based. They focus on regenerative farming practices and they focus on staple root crops and cabbage. So from the very beginning, as we first started with these smaller products, we started buying cabbage from them. Twice a year we sit down with them with the planting planning: What do you think it’s going to look like this year? How many plugs on your side can you plant for us?

Super Tuber is really into this idea and I love it — they harvest in reusable bins in the field, then bring them straight to us in reusable bins. When you work with farms, produce comes in paraffin or wax boxes. Those go straight in the landfill. We are trying to have as little waste as possible. We’d love to never receive anything in wax boxes, and we’re there about 95% of the time. We compost everything that comes out of the kitchen.

Another thing, the cabbage isn’t wrapped in plastic packaging. We peel off the outer cabbage leaves as we prep in the kitchen. Those outer leaves are what I like to layer on top to seal everything. It weighs the ferment batch down and provides a nice layer if there’s ever an impurity — which really doesn’t happen — so if we ever discard anything, it’s those top leaves that would normally get composted.

What was the biggest turning point for your brand to go from selling at farmer markets to getting in stores?

CFM: Honestly, as corporate as Whole Foods is, they have a wonderful way of supporting small brands. The west coast is filled with small ferment companies trying so hard and not succeeding at getting in. Whole Foods saw potential in us. That was really the turning point for our company. And they’ve continued to be loyal to us. Not all chains are pleasant to work with, but we made big moves through Whole Foods. It opened up this door to the Bay Area independents, like the Good Food Mercantile and the Good Food Awards. The Bay Area independents are so cutting edge in a way that I think a lot of these big chains strive to be as far as the products that they bring in and the diversity they really search for in craft products. At this point, we’re almost everywhere in the greater Bay Area that we’ve set out to be in — and I do think that started with getting in Whole Foods in 2020.

TFA: How were you distributing before that?

CFM: We were driving all over Northern California. We would drive five hours round trip to drop off like 10 cases of kraut. It did not make sense long term. Now we work with Tony’s Fine Foods to distribute to the pacific region. Tony’s has been supportive from the beginning.

We still self distribute locally, but only whatever we can do in a 20 minutes drive. The local support that we have, that started with our stands at the farmers market and then our storefront, that support has been amazing. Like we honestly sell more in our local co-op then we do in 40 stores in the Pacific Northwest. That kind of local support will always be there.

TFA: That’s great that you have a big local fan base.

CFM: When we decided to get going in Grass Valley, we opened up a store front for a year-and-a-half and had this really great interface with our community. We were really experimental in those years. That was the year I was coming up with a lot of small batches. When we were invited to be in the Whole Foods, we had to move to a distributor and palletize. Things were not so small batch anymore. Right as the pandemic hit, we started being received really well in the west coast. We streamlined the products that people really wanted. We’ve got our favorite line of krauts, our different kimchis. We still do a lot of hot sauces and brine tonics.

TFA: What is your favorite flavor?

CFM: Turmeric Ginger Jalapeno is my go-to, everyday. My body craves it. Our Beet Fennel though outsells anything we carry. People love it.

TFA: You’ve gone from fermenting in your home kitchen to distributing regionally. What do you think has been your biggest lesson in all of this?

CFM: Not giving up. Listening to the ferments — it sounds really weird, but I literally have studied patterns in the life within the fermenters. For example, we have these variable capacity lids that have an airlock on the top where the brine can spit out. In certain ebbs and flows, I think it’s astrological, all the fermenters will come to life, no matter how old they are. Or in a certain cycle of the moon, all of them will compact and leave an air pocket that I have to reset. It is crazy, witnessing the nature and patterns.

Through all the trial and error and discouragement, it’s the life of the microbiology itself that is really the inspiring thing. I could never get it right, it’s always going to be different no matter what. But I’m getting a lot better at creating that perfect environment for consistency. If you ask me — I’m living and breathing it because I digest this all the time.

TFA: Where do you see the future of fermentation?

CFM: I see it growing. It is beyond all the trends, it’s something that’s been around for ages, for centuries, and there’s a reason why it’s always been incorporated in our diets. There’s this sense of awakening that so many people in the mainstream are feeling — if it’s kombucha, if it’s sauerkraut, if it’s kefir, if it’s yogurt — people are really feeling the benefits. The pandemic has had a huge influence on that, too. I think everyone in grocery would agree fermentation is a big thing right now and it deserves to be a big thing.

- Published in Business, Food & Flavor

“Bacterial Bully” Could Create Healthier & Tastier Fermented Foods

Microbiologists have long considered that there are two distinct categories of energy conservation in microorganisms: fermentation and respiration. Lactic acid bacteria (LAB) use fermentation, making it central to food and drink production and preservation since the dawn of man.

But researchers at the University of California, Davis, and Rice University discovered a LAB species that uses a hybrid metabolism, combining both fermentation and respiration.

“These are two very different things, to the extent that we classify bacteria as basically one or the other,” said Caroline Ajo-Franklin, a bioscientist at Rice University and co-author of the study. “There are examples of bacteria that can do both, but that’s like saying I can ride a bicycle or I can drive a car. You never do both at the same time.”

“What we discovered is a LAB that blends the two, like an organism that’s not warm- or cold-blooded but has features of both,” she said. “That’s the big surprise, because we didn’t know it was possible for an organism to blend these two distinct metabolisms.”

The species — lactiplantibacillus plantarum — is what scientists call a bacterial bully because it takes advantage of two distinct metabolic processes, according to a press release from Rice on the study. These systems were “not previously known to coexist to acquire the fuel they burn for energy.”

“Using this blended metabolism, lactic acid bacteria like L. plantarum grow better and do a faster job acidifying its environment,” said Maria Marco, a professor in the food science and technology department at UC Davis and the study’s co-author [and a TFA Science Advisor].

The discovery is significant for food and chemical production. New technologies that use LAB could now produce healthier and tastier ferments, minimize food waste and change the flavors and textures of fermented food.

“We may also find that this blended metabolism has benefits in other habitats, such as the digestive tract,” Marco said. “The ability to manipulate it could improve gut health.”

The study began with a puzzle: the realization that genes responsible for the electron transfer pathway in mainly respiratory organisms also appear in the LAB genome. “It was like finding the metabolic genes for a snake in a whale,” Ajo-Franklin said. “It didn’t make a lot of sense, and we thought, ‘We’ve got to figure this out.’”

While the Davis lab studied the genome, the team at Rice carried out fermentation experiments on kale.

“It wasn’t our first choice,” said Rice alumna and co-lead author Sara Tejedor-Sanz (now a senior scientific engineer in the Advanced Biofuels and Bioproducts Process Development Unit at Lawrence Berkeley National Lab).

“We performed some initial experiments with cabbage, since that’s a known fermented food — sauerkraut and kimchi — in which lactic acid bacteria are present,” she said. “But there were technical difficulties and it didn’t turn out so well. So we looked for another food to ferment where LAB could be found in its ecological niches.

“Kale has compounds like vitamins and quinones that lactic acid bacteria use as cofactors in their metabolism, and are also involved in interacting with the electrodes,” she said. “We also found fermenting kale to make juice was a trend. It sounded perfect for our biochemical reactors.”

The study showed LAB enhances metabolism through a FLavin-based Extracellular Electron Transfer (FLEET) pathway that expresses two genes (ndh-2 and pp1A) associated with iron reduction, a step in the process of stripping and incorporating electrons into ATP (adenosine triphosphate (ATP), energy-carrying molecule).

Because LAB’s genome has evolved to be small, thus requiring less energy to maintain, the wide conservation of FLEET must serve a purpose, Ajo-Franklin said.

“Our hypothesis is this helps bacteria get established in new environments,” she said. “It’s a way to kick-start their metabolisms and outcompete their neighbors by changing the environment to be more acidic. It’s being a bully.”

That the FLEET pathway can be triggered with electrodes offers many possibilities, she said. “We found we can use the hybrid metabolism in food fermentation,” Ajo-Franklin said. “Now we have a way to change how food may taste and avoid failed food fermentations by using electronics.”

“We may also find that this blended metabolism has benefits in other habitats, such as the digestive tract,” Marco said. “The ability to manipulate it could improve gut health.”

Ajo-Franklin noted LAB are commonly found in the microbiomes of many organisms, including humans. “You can already buy it in health food stores as a probiotic,” she said. “The human gut is an anaerobic environment, so LAB have to keep a redox balance. If it oxidizes carbon to gain energy, it has to figure out a way to reduce carbon somewhere else.

“Now we think if we provide another electron donor or acceptor, we could promote the growth of positive bacteria over negative bacteria.”

UC Davis graduate student Eric Stevens is co-lead author of the study. Co-authors are Rice graduate student Siliang Li; at UC Davis, graduate students Peter Finnegan and James Nelson, and Andre Knoesen, a professor of electrical and computer engineering, at UC Davis; and Samuel Light, the Neubauer Family Assistant Professor of Microbiology at the University of Chicago.

Ajo-Franklin is a professor of biosciences and a CPRIT Scholar. Marco is a professor of food science and technology.

The National Science Foundation, Office of Naval Research, the Department of Energy Office of Basic Energy Sciences and a Rodgers University fellowship supported the research.

The study results were published in the journal eLife.

- Published in Food & Flavor, Health, Science

Is Fermentation “So White”…or Not?

More international fermented foods and beverages are entering the American food scene, an exciting development in an expanding market. But the origins of many of these traditional dishes get blurred by western producers.

In a panel on diversity and cultural appropriation during TFA’s conference FERMENTATION 2021, BIPOC food professionals encouraged fermenters to innovate with food from different countries, but to be mindful of their approach. A dish’s culture must be respected, its history acknowledged and negative stereotypes eliminated. The talk “Is Fermentation ‘So White’…or Not?” included panelists Miin Chan (educator and writer working on her PhD), Jiayang Fan (staff writer for The New Yorker), Mara Jane King (director of fermentation for IE Hospitality), Kheedim Oh (founder of Mama O’s Premium Kimchi, and TFA Advisory Board member) and Sebastian Vargo (founder of Vargo Brother Ferments).

Last year, two articles helped propel a conversation on diversity among fermenters. One was Fan’s New Yorker article “The Gatekeepers Who Get to Decide What Food is Disgusting,” which highlights how a western view of “disgusting” food requires immigrants to assimilate to local food cultures. Another was Chan’s Eater article “Lost in the Brine,” which explores cultural appropriation in fermentation.

Oh expressed his frustration watching companies produce kimchi without any cultural ties to or acknowledgement of its Korean history. Vargo agreed.

“Whether it is financial or just overall exposure, you really can’t deny the fact that oftentimes…a white face or a white person borrowing off the culture will oftentimes achieve higher amounts of success,” Vargo says. Kimchi has exploded in popularity in the U.S. the past few years – and some white producers receive more funding than traditional Korean companies. “They’re overshadowing the people that actually deserve to have their stories told in the first place.”

Traditional ferments can get watered down, tailored to follow food trends instead of staying true to their historical roots. Chan pointed out that, in Australia, there’s no regulation around labeling certain foods. Pickled cucumbers could be labeled as kimchi, appealing to western consumer tastes.

“Whether it’s in fermentation or the food industry or just any industry that we exist in within this capitalist system, there’s systemic racism and there’s some historical forces that mean that BIPOC basically often have less access to social and financial capital,” she adds.

Cookbook author Alison Roman came under fire when she released a curry recipe she labeled as a stew. There was no history detailing curry’s Southeastern Asian roots and no context of where the recipe idea originated.

“She literally whitewashed all of the culture out of it and made it into something that she could sell,” King said. “Labeling something to suit you and to suit your benefit and your profit can be harmful to people of color.”

It’s a problem in restaurant reviews too, Fan pointed out. Food critics tend to draw a western comparison to more exotic cuisines, comparing an Asian rice dish to a pasta, for example, offering their own translation. She recently wrote a review on a hot pot restaurant in New York and felt compelled to compare it to fondue. She had a limited word count and wanted to be succinct. But a coworker asked: Why not just explain what it is?

“In the process of being a writer, a critic, (I need) to introduce those words in the cultural lexicon so that the western standard isnt kind of the defacto comparison for everything,” she said.

Who decides French cuisine is more elevated than Chinese, Oh questions.

“I think that’s the huge problem is that there’s so much inherent cultural bias that even we as minorities too will have within ourselves that keeps getting perpetuated,” Oh says, noting people of color are not pigeonholed to only cooking their traditional food, too.

Society needs to value traditional cooking arts so food history and knowledge – especially from more rural parts of the world – isn’t lost, Chan adds.

“I think we’ve come around now, the work that (the panelists) and many other fermenters do shows we want to be connected to our traditional food system, we don’t want to lose these tastes and we want to understand our microbial heritages,” she says.

- Published in Business, Food & Flavor

Covid & the 4k’s: 4 Foods “Many People Don’t Know About”

Renowned professor, epidemiologist and author of The Diet Myth and Spoon Fed Tim Spector is encouraging people to eat the 4k’s: kefir, kombucha, kimchi and kraut. His studies found diet plays a role in preventing severe symptoms of Covid.

Spector is a leading expert on long Covid, the symptoms that can continue for extended periods after an initial infection. He leads the ZOE Covid Study, created by scientists and doctors at King’s College London (where he is based), Stanford, Harvard, Massachusetts General Hospital and health science company ZOE. Last year Spector helped research the attributes and predictors of long Covid, the results of which were published in the journal Nature Medicine.

A microbiome researcher, Spector advocates for people to eat a diverse diet to improve the trillions of microbes in the gut.

“We know from Covid now that your gut health is crucial for your immune system,” he told ITV. “If we can focus on our gut health…gut microbiome is really crucial.”

Diet must be high-quality to improve immunity, he stresses. In the ZOE Covid study, researchers have found eating “the right things and avoiding feeding (the gut) the bad things, that’s what made the difference to getting long Covid,” he said. Fermented foods have proven health benefits, but Spector says many people opt for cheaply-made yogurts and cheeses prevalent in the grocery store to get their daily dose of fermented foods. This dairy is full of sugar and artificial ingredients, which thwart the positive effects of fermentation.

“The other fermented foods that many people don’t know about are what I call the 4 k’s,” Spector says: kefir, kombucha, kimchi and kraut (sauerkraut). He encourages “small shots a day” of a fermented food or beverage. “That really is a powerful enhancer of your microbes. And all these things are going to be cheaper actually than taking multivitamins every day of your life.”

Spector is not a fan of supplements, like pill forms of vitamins and nutrients. Many are proven not to work, he explained. In his studies on the effects of supplements on long Covid, there were minimal benefits for women and none for men.

“People are much better off getting all their vitamins and nutrients by having a diverse diet,” Spector said.

- Published in Food & Flavor, Science

Retail Sales Trends for Fermented Products

Miso, frozen yogurt and pickled and fermented vegetables are driving growth in the $10.97 billion fermented food and beverage category. The fermented products space grew 3.3% in 2021, outpacing the 2.1% growth achieved by natural products overall.

“It really highlights how functional products have become the norm for shoppers when they’re in stores,” says Brittany Moore, Data Product Manager for Product Intelligence at SPINS LLC, a data provider for natural, organic and specialty products. Moore notes there’s an “explosion of functional products” in the market — “[they] are appearing everywhere. And fermented products have been leading that space in the natural market for years.”

The data was shared during TFA’s conference, FERMENTATION 2021. SPINS worked with TFA to drill into data covering 10 fermented product categories and 64 product types (an increase from last year). [A note that wine, beer and cheese sales are excluded from the data. These categories are very large, and would obscure trends in smaller segments. Wine, beer and cheese are also well-represented by other organizations.]

Yogurt dominates the fermented food and beverage landscape with 75% of the market, but sales growth is soft. Frozen yogurt and plant-based offerings, though small portions of the yogurt category, are fueling what growth there is. “Novelty products are catching shopper’s eyes,” Moore notes.

Kombucha, the fermented tea which led the U.S. retail revival of fermented products, still rules the non-alcoholic fermented beverages market, with 86% of sales. But growth is slowing. Moore points out that this slowdown is due to kombucha having penetrated the mass market with lots of brands on grocery shelves.

“There’s opportunity in kombucha for new innovations to catch the progressive shopper’s eye,” Moore says. “Shoppers are looking for an innovative twist to their functional product.”

Moore points to successful twists like hard kombucha, which grew nearly 60%, and probiotic sodas, which grew 31%.

Growth is slowing for hard cider, too, though hard cider leads the alcoholic beverages category with 83% share of sales.

All sectors of the pickled and fermented vegetables category are growing, totalling nearly $563 million in sales. Refrigerated products are nine of the top 10 subcategories here. The “other” pickled vegetable subcategory is increasing at a 60% growth rate, “other” being the catch-all for vegetables that are not cucumbers, cabbage, carrots, tomatoes, beets or ginger. Fermented radish, garlic and seaweed fall into this subcategory.

Soy sauce is not surprisingly still the largest product in sauces, representing 58% of the category. But that share is dropping. Gochujang is the growth leader, increasing at rate of nearly 20%.

Miso and tempeh are also performing well, which Moore attributes to the growing plant-based movement and the Covid-19 pandemic pantry stocking boom. Miso products — soups, broths, pastes and mixes — totaled over $24 million in sales in 2021. Though instant soups and meal cups represented only 8% of sales, they grew more than 110%.

- Published in Business

“Our Customers Do Not Even Know What is a Fermented Item”

Fermentation is cloaked in mystery for many — it’s bubbly, slimy, stinky and not always Instagram-ready. In The Fermentation Association’s recent member survey, this lack of

understanding of fermentation and its flavor and health attributes among consumers was cited by 70% of producers as a major obstacle to increased sales and acceptance of fermented products.

“We get so many questions from our readers about fermentation. People are very interested, but have very, very little knowledge about it,” says Anahad O’Connor, reporter for The New York Times. O’Connor has written about fermented foods multiple times in the last few months, and those articles were among The Times’ most emailed pieces of 2021. “I think there’s a huge opportunity to educate consumers about fermented foods, their impact on the gut and health in general.”

O’Connor spoke on consumer education as part of a panel of experts during TFA’s conference, FERMENTATION 2021. Panelists — who included a producer, retailer, scientist, educator and journalist — agreed consumer education is lacking. But the methods of how to fill that gap are contested.

How to Tell Consumers “What is a Fermented Food?”

There are differences between what is a fermented product and what is not — a salt brine vs. vinegar brine pickle, or a kombucha made with a SCOBY or one from a juice concentrate, for example.

“I can tell you that the majority of our customers do not even know [what is a] fermented item,” says Emilio Mignucci, vice president of Philadelphia gourmet store Di Bruno Bros., which specializes in cheese and charcuterie. When customers sample products at the store, they can easily taste the differences between a fermented and a non-fermented product, Mignucci says. But he feels the health benefits behind that fermented product are not the retailer’s responsibility to communicate. “I need you guys [producers] to help me deliver the message.”

“Retailers like myself, buyers, we want to learn more to be able to champion [fermented foods] because, let’s face it, fermented foods is a category that’s getting better and better for us as retailers and we want to speak like subject matter experts and help our guests understand.”

Now — when fermentation tops food lists and gut health is mainstream — is the time for education.

“This microbiome world that we’re in right now is sort of a really opportune moment to really help the public understand what fermented foods are beyond health,” says Maria Marco, PhD, professor of food science at the University of California, Davis (and a TFA Advisory Board Member).

Kombucha Brewers International (KBI) created a Code of Practice to address confusion over what is or is not a kombucha. KBI is taking the approach that all kombucha is good, pasteurized or not, because it’s moving consumers away from sugar- and additive-filled sodas and energy drinks.

“That said, consumers deserve the right to know why is this kombucha at room temperature and this kombucha is in the fridge and why does this kombucha have a weird, gooey SCOBY in it and this one is completely clear,” says Hannah Crum, president of KBI. “They start to get confused when everything just says the word ‘kombucha’ on it.”

KBI encourages brewers to be transparent with consumers. Put on the label how the kombucha is made, then let consumers decide what brand they want to buy.

Should Fermented Products Make Health Claims?

Drew Anderson, co-founder and CEO of producer Cleveland Kitchen (and also on TFA’s Advisory Board), says when they were first designing their packaging in 2013, they were advised against using the term “crafted fermentation” on their label because it would remind consumers of beer or wine. But nowadays, data shows 50% of consumers associate the term fermentation with health.

“In the last five to six years, it’s changed dramatically and people are associating fermentation as being good for them, which is good for my products,” he says.

Cleveland Kitchen, though, does not make health claims on their fermented sauerkraut, kimchi and dressings. Anderson says, as a small startup, they don’t have the resources to fund their own research. They instead attract customers with bold taste and striking packaging.

“We’re extremely cautious on what we say on the package because we don’t have an army of lawyers like Kevita (Pepsi’s Kombucha brand), we don’t have the Pepsi legal team backing us here,” Anderson says. Cleveland Kitchen submits new packaging designs in advance to regulators, to make sure they’re legally acceptable before rolling them out.

O’Connor says taste is the No. 1 driver for consumers. This is why healthful but sticky and stinky natto (fermented soybeans) is not a popular dish in America, but widely consumed in Japan.

“Many American consumers, unfortunately, aren’t going to gravitate toward that, despite the health benefits,” he says.

Crum disagrees. “Health comes first,” she says. As more and more kombucha brands emphasize lifestyle, and don’t even advertise their health benefits, she feels they are doing a disservice to the consumer. “Why pay that much money for kombucha if you don’t know it’s good for you too?”

- Published in Business, Food & Flavor, Health, Science

The Rise of Fermented Foods and -Biotics

Microbes on our bodies outnumber our human cells. Can we improve our health using microbes?

“(Humans) are minuscule compared to the genetic content of our microbiomes,” says Maria Marco, PhD, professor of food science at the University of California, Davis (and a TFA Advisory Board Member). “We now have a much better handle that microbes are good for us.”

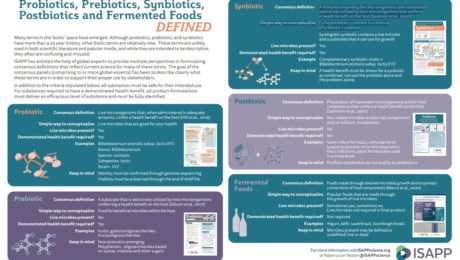

Marco was a featured speaker at an Institute for the Advancement of Food and Nutrition Sciences (IAFNS) webinar, “What’s What?! Probiotics, Postbiotics, Prebiotics, Synbiotics and Fermented Foods.” Also speaking was Karen Scott, PhD, professor at University of Aberdeen, Scotland, and co-director of the university’s Centre for Bacteria in Health and Disease.

While probiotic-containing foods and supplements have been around for decades – or, in the case of fermented foods, tens of thousands of years – they have become more common recently . But “as the terms relevant to this space proliferate, so does confusion,” states IAFNS.

Using definitions created by the International Scientific Association for Postbiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP), Marco and Scott presented the attributes of fermented foods, probiotics, prebiotics, synbiotics and postbiotics.

The majority of microbes in the human body are in the digestive tract, Marco notes: “We have frankly very few ways we can direct them towards what we need for sustaining our health and well being.” Humans can’t control age or genetics and have little impact over environmental factors.

What we can control, though, are the kinds of foods, beverages and supplements we consume.

Fermented Foods

It’s estimated that one third of the human diet globally is made up of fermented foods. But this is a diverse category that shares one common element: “Fermented foods are made by microbes,” Marco adds. “You can’t have a fermented food without a microbe.”

This distinction separates true fermented foods from those that look fermented but don’t have microbes involved. Quick pickles or cucumbers soaked in a vinegar brine, for example, are not fermented. And there are fermented foods that originally contained live microbes, but where those microbes are killed during production — in sourdough bread, shelf-stable pickles and veggies, sausage, soy sauce, vinegar, wine, most beers, coffee and chocolate. Fermented foods that contain live, viable microbes include yogurt, kefir, most cheeses, natto, tempeh, kimchi, dry fermented sausages, most kombuchas and some beers.

“There’s confusion among scientists and the public about what is a fermented food,” Marco says.

Fermented foods provide health benefits by transforming food ingredients, synthesizing nutrients and providing live microbes.There is some evidence they aid digestive health (kefir, sourdough), improve mood and behavior (wine, beer, coffee), reduce inflammatory bowel syndrome (sauerkraut, sourdough), aid weight loss and fight obesity (yogurt, kimchi), and enhance immunity (kimchi, yogurt), bone health (yogurt, kefir, natto) and the cardiovascular system (yogurt, cheese, coffee, wine, beer, vinegar). But there are only a few studies on humans that have examined these topics. More studies of fermented foods are needed to document and prove these benefits.

Probiotics

Probiotics, on the other hand, have clinical evidence documenting their health benefits. “We know probiotics improve human health,” Marco says.

The concept of probiotics dates back to the early 20th century, but the word “probiotic” has now become a household term. Most scientific studies involving probiotics look at their benefit to the digestive tract, but new research is examining their impact on the respiratory system and in aiding vaginal health.

Probiotics are different from fermented foods because they are defined at the strain level and their genomic sequence is known, Marco adds. Probiotics should be alive at the time of consumption in order to provide a health benefit.

Postbiotics

Postbiotics are dead microorganisms. It is a relatively new term — also referred to as parabiotics, non-viable probiotics, heat-killed probiotics and tyndallized probiotics — and there’s emerging research around the health benefits of consuming these inanimate cells.

“I think we’ll be seeing a lot more attention to this concept as we begin to understand how probiotics work and gut microbiomes work and the specific compounds needed to modulate our health,” according to Marco.

Prebiotics

Prebiotics are, according to ISAPP, “A substrate selectively utilized by host microorganisms conferring a health benefit on the host.”

“It basically means a food source for microorganisms that live in or on a source,” Scott says. “But any candidate for a prebiotic must confer a health benefit.”

Prebiotics are not processed in the small intestine. They reach the large intestine undigested, where they serve as nutrients for beneficial microorganisms in our gut microbiome.

Synbiotics

Synbiotics are mixtures of probiotics and prebiotics and stimulate a host’s resident bacteria. They are composed of live microorganisms and substrates that demonstrate a health benefit when combined.

Scott notes that, in human trials with probiotics, none of the currently recognized probiotic species (like lactobacilli and bifidobacteria) appear in fecal samples existing probiotics.

“There must be something missing in what we’re doing in this field,” she says. “We need new probiotics. I’m not saying existing probiotics don’t work or we shouldn’t use them. But I think that now that we have the potential to develop new probiotics, they might be even better than what we have now.”

She sees great potential in this new class of -biotics.

Both Scott and Marco encouraged nutritionists to work with clients on first improving their diets before adding supplements. The -biotics stimulate what’s in the gut, so a diverse diet is the best starting point.

Cabbage Shortage Forces Halt in Winter Kimchi

A cabbage shortage is forcing North Koreans to give up winter kimchi making for the second year in a row. They are unable to take part in gimjang, the Korean tradition of communally preparing kimchi each October for the winter season.

Flood damage and poor crop yields led to a poor cabbage (and radish) growing season. The cabbage that was harvested was mostly routed to military and government agencies, “leaving the people empty handed.” Cabbage prices have risen 25% from a year ago, “making a large batch of kimchi cost more than a government-provided monthly salary,” according to Radio Free Asia.

Read more (Radio Free Asia)

- Published in Business, Food & Flavor

Global Kimchi Boom

South Korea’s exports of kimchi are at a record high — they have increased nearly 14% year-over-year in 2021 through August.Exports were highest to Japan ($57.2 million), U.S. ($18.9 million) and Hong Kong ($5.4 million). South Korea is expected to have a trade surplus in kimchi for the first time in 12 years.

Korea Customs Service and food industry experts attribute the rise to a few factors. First, growing consumer desire for healthier food. Second, kimchi is regularly highlighted by the media during the Covid-19 outbreak as a food that can boost immunity (note that this has not been scientifically proven). And third, “foreigners’ greater interest in Korean foods thanks to the popularity of Korean pop culture abroad.”

Read more (Korea Business Wire)

- Published in Business