Fermentation vs. Fiber — Both Help, but Fermentation Shines

A diet high in fermented foods increases microbiome diversity, lowers inflammation, and improves immune response, according to researchers at Stanford University’s School of Medicine.The groundbreaking results were published in the journal Cell.

In the clinical trial, healthy individuals were fed for 10 weeks, a diet either high in fermented foods and beverages or high in fiber. The fermented diet — which included yogurt, kefir, cottage cheese, kimchi, kombucha, fermented veggies and fermented veggie broth — led to an increase in overall microbial diversity, with stronger effects from larger servings.

“This is a stunning finding,” says Justin Sonnenburg, PhD, an associate professor of microbiology and immunology at Stanford. “It provides one of the first examples of how a simple change in diet can reproducibly remodel the microbiota across a cohort of healthy adults.”

Researchers were particularly pleased to see participants in the fermented foods diet showed less activation in four types of immune cells. There was a decrease in the levels of 19 inflammatory proteins, including interleukin 6, which is linked to rheumatoid arthritis, Type 2 diabetes and chronic stress.

“Microbiota-targeted diets can change immune status, providing a promising avenue for decreasing inflammation in healthy adults,” says Christopher Gardner, PhD, the Rehnborg Farquhar Professor and director of nutrition studies at the Stanford Prevention Research Center. “This finding was consistent across all participants in the study who were assigned to the higher fermented food group.”

Microbiota Stability vs. Diversity

Continues a press release from Stanford Medicine News Center: By contrast, none of the 19 inflammatory proteins decreased in participants assigned to a high-fiber diet rich in legumes, seeds, whole grains, nuts, vegetables and fruits. On average, the diversity of their gut microbes also remained stable.

“We expected high fiber to have a more universally beneficial effect and increase microbiota diversity,” said Erica Sonnenburg, PhD, a senior research scientist at Stanford in basic life sciences, microbiology and immunology. “The data suggest that increased fiber intake alone over a short time period is insufficient to increase microbiota diversity.”

Justin and Erica Sonnenburg and Christopher Gardner are co-authors of the study. The lead authors are Hannah Wastyk, a PhD student in bioengineering, and former postdoctoral scholar Gabriela Fragiadakis, PhD, now an assistant professor of medicine at UC-San Francisco.

A wide body of evidence has demonstrated that diet shapes the gut microbiome which, in turn, can affect the immune system and overall health. According to Gardner, low microbiome diversity has been linked to obesity and diabetes.

“We wanted to conduct a proof-of-concept study that could test whether microbiota-targeted food could be an avenue for combatting the overwhelming rise in chronic inflammatory diseases,” Gardner said.

The researchers focused on fiber and fermented foods due to previous reports of their potential health benefits. High-fiber diets have been associated with lower rates of mortality. Fermented foods are thought to help with weight maintenance and may decrease the risk of diabetes, cancer and cardiovascular disease.

The researchers analyzed blood and stool samples collected during a three-week pre-trial period, the 10 weeks of the diet, and a four-week period after the diet when the participants ate as they chose.

The findings paint a nuanced picture of the influence of diet on gut microbes and immune status. Those who increased their consumption of fermented foods showed effects consistent with prior research showing that short-term changes in diet can rapidly alter the gut microbiome. The limited changes in the microbiome for the high-fiber group dovetailed with previous reports of the resilience of the human microbiome over short time periods.

Designing a suite of dietary and microbial strategies

The results also showed that greater fiber intake led to more carbohydrates in stool samples, pointing to incomplete fiber degradation by gut microbes. These findings are consistent with research suggesting that the microbiome of a person living in the industrialized world is depleted of fiber-degrading microbes.

“It is possible that a longer intervention would have allowed for the microbiota to adequately adapt to the increase in fiber consumption,” Erica Sonnenburg said. “Alternatively, the deliberate introduction of fiber-consuming microbes may be required to increase the microbiota’s capacity to break down the carbohydrates.”

In addition to exploring these possibilities, the researchers plan to conduct studies in mice to investigate the molecular mechanisms by which diets alter the microbiome and reduce inflammatory proteins. They also aim to test whether high-fiber and fermented foods synergize to influence the microbiome and immune system of humans. Another goal is to examine whether the consumption of fermented foods decreases inflammation or improves other health markers in patients with immunological and metabolic diseases, in pregnant women, or in older individuals.

“There are many more ways to target the microbiome with food and supplements, and we hope to continue to investigate how different diets, probiotics and prebiotics impact the microbiome and health in different groups,” Justin Sonnenburg said.

Other Stanford co-authors are Dalia Perelman, health educator; former graduate students Dylan Dahan, PhD, and Carlos Gonzalez, PhD; graduate student Bryan Merrill; former research assistant Madeline Topf; postdoctoral scholars William Van Treuren, PhD, and Shuo Han, PhD; Jennifer Robinson, PhD, administrative director of the Community Health and Prevention Research Master’s Program and program manager of the Nutrition Studies Group; and Joshua Elias, PhD.

Researchers from the nonprofit research center Chan-Zuckerberg Biohub also contributed to the study. Here’s the complete press release from Stanford Medicine News Center.

Korea’s Controversial Kimchi Book

As China and Korea continue to clash over where kimchi originated, the Korean government has published a book laying their claim.

“Kimchi in the Eyes of the World” contains history, recipes, stories from writers who love to eat kimchi, and how traditional Korean kimchi is different from China’s pao cai, a pickled vegetable dish.

The 148-page book was published by the Korean Culture and Information Service and the Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs. They plan to distribute it in Korean- and English-language versions through overseas Korean Culture Centers and via the foreign embassies in Korea.

Read more (The Korea Herald)

- Published in Business, Food & Flavor

Bubbling Over: Why Kimchi Is the Fastest-Growing Fermented Veggie in America

Sales are soaring. Although kimchi only makes up 7% of the pickles and fermented vegetables category, its sales are increasing at an explosive 90% rate, according to SPINS.

We asked three kimchi experts their thoughts on the uptick in sales: Minnie Luong, founder and CHI-EO of Chi Kitchen, JinJoo Lee, chef and Korean Food Blogger at KimchiMari and Kheedim Oh, founder and Chief Minister of Kimchi for Mama O’s (and member of TFA’s Advisory Board).

We asked them: Why do you think kimchi sales are increasing so rapidly?

Minnie Luong: Originating in Korea around 4,000 years ago, kimchi is an iconic food symbolic of hope, trust, and survival that is the perfect food for our current times. One of the world’s most special foods, it elicits delight, storytelling and sharing. In fact, UNESCO has designated kimjang — the traditional way of making and sharing kimchi — a designated intangible cultural heritage of humanity.

Low in calories, high in fiber and big on flavor that’s great for your digestion and gut health, kimchi is uniquely poised to cross over from being a specialty food to a must-have pantry staple for health and wellness enthusiasts, home cooks and those seeking out a satisfying flavor adventure. Its spicy, tangy, umami flavor is convenient and easy to use across a wide range of dishes along with a long shelf life when refrigerated. Just open a jar and it’s ready to go! While kimchi is often seen as a condiment, it should really be considered a vegetable, but one that packs a delicious, probiotic punch. Let’s face it, we could all use more veggies and flavor in our lives!

JinJoo Lee: I think the sales of kimchi are increasing because more and more people are aware of the health benefits of kimchi (loaded with probiotics like many fermented foods) and also are being introduced to the wonderful flavors of it now through many restaurant foods and magazine recipes.

More restaurants have started to use kimchi in their menu because I think chefs have realized kimchi works great in non-Korean dishes such as on hamburgers, pasta, cheese quesadillas and even with Brussels sprouts!

Kimchi has a very deep and complex flavor with an amazing zing that fermented foods have but it also is a perfect balance of sour, spicy, salty, umami and slightly sweet that works well with so many different foods, especially meats and seafood.

Most Americans may know only the spicy napa cabbage kimchi (Baechu Kimchi) but did you know there are over 100 different kimchis? kimchi can be made using all sorts of different vegetables such as cucumber, eggplant, radish, mustard greens, green onions, chives and more.

If made and stored properly, kimchi can last for weeks, months and years and it can be enjoyed throughout all the different stages of fermentation – from the very beginning as fresh tasting to fully ripe to overly ripe and sour then even when it’s aged for years! So kimchi is the perfect fermented food that’s tasty, healthy, versatile and even long-lasting.

Kheedim Oh: With everyone in the world simultaneously experiencing sensations of uncertainty mixed with mortal fears of peer contact, people are drawn to the near mythic powers of kimchi. One of the top 5 healthiest foods in the world (according to Health Magazine). A true superfood. People are attracted to the promises of probiotics. The comfort of supporting their immune systems with each bite. The flavor of fermentation. The addictive nature of how eating good kimchi makes you feel.

The word kimchi has reached a tipping point where it’s no longer just the stinky rotting cabbage from Korea (or wherever) to the acidic/tart vegetable dish that “I had as part of a dish at the insert [trendy fusion restaurant] that I went to and I heard it’s really good for you.” It’s losing its Korean-ness and quickly being subsumed into White American food culture the way that kombucha has already completely become. There are a lot of “kimchis” that are only kimchi through very loose interpretations or are just not real kimchi by any definition, only by name. The culprits being many of the before-mentioned fusion restaurants.

On the other hand, there is the whole DIY home fermentation movement that has been growing year over year. Educating themselves on how to achieve food sovereignty, they tend to be a more culturally sensitive crowd. Regardless of the hype surrounding the word, we hope that kimchi can maintain its popularity in America while maintaining its unique UNESCO World Heritage recognized cultural identity as a Korean food.

- Published in Business, Food & Flavor

Ugly Delicious

A unique business practice has been developed in Montana by Farmented Foods — the company ferments discarded produce from local growers to fill their jars with the likes of radish kimchi, dill sauerkraut and spicy carrot chips. The co-owners (Vanessa Walsten and Vanessa Williamson) met in 2016 at a Farm to Market class at Montana State University. They are currently getting ready to renovate a former cafe into a fermentation kitchen, thanks to a grant from the Montana Agriculture Development Council.

“Every year, so much produce is wasted because we don’t deem it perfect enough,” says Williamson, adding that the company “was founded initially to help farmers eliminate unnecessary food loss on their farms in the form of ugly and excess crops.”

They estimate they’ve saved over 6,000 pounds of imperfect produce.

Read more (Daily Inter Lake)

- Published in Business

The New Definition of Fermented Food

After Dr. Bob Hutkins finished a presentation on fermented foods during a respected nutrition conference, the first audience question was from someone with a PhD in nutrition: “What are fermented foods?”

“I thought ‘Doesn’t everyone know what fermentation is?’ I realized, we do need a definition. Those of us that work in this field know what we’re talking about when we say fermented foods, but even people trained in foods do not understand this concept,” says Hutkins, a professor of food science at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. He presented The New Definition of Fermented Foods during a webinar with TFA.

Hutkins was part of a 13-member interdisciplinary panel of scientists that released a consensus definition on fermented foods. Their research, published this month in Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology, defines fermented foods as: “foods made through desired microbial growth and enzymatic conversions of food components.”

“We needed a definition that conveyed this simple message of a raw food turning into a fermented food via microorganisms,” Hutkins says. “It brings some clarity to many of these issues that, frankly, people are confused about.”

David Ehreth, president and founder of Alexander Valley Gourmet, parent company of Sonoma Brinery (and a TFA Advisory Board member), agreed that an expert definition was necessary.

“As a producer, and having started this effort to put live culture products on the standard grocery shelf, I started doing it as a result of unique flavors that I could achieve through fermentation that weren’t present in acidified products,” Ehreth says. “Since many of us put this on our labels, we should be paying close attention to what these folks are doing, since they are the scientific backbone of our industry.”

Hutkins calls fermented foods “the original shelf-stable foods.” They’ve been used by humankind for over thousands of years, but have mushroomed in popularity in the last 15. Fermented foods check many boxes for hot food trends: artisanal, local, organic, natural, healthy, flavorful, sustainable, innovative, hip, funky, chic, cool and Instagram-worthy.

Nutrition, Hutkins hypothesizes, is a big driver of the public’s interest in fermentation. He noted that Today’s Dietitian has voted fermented foods a top superfood for the past four years.

Evidence to make bold claims about the health benefits of fermentation, though, is lacking. Hutkins says there is observational and epidemiological evidence. But randomized, human clinical trials — “the highest evidence one can rely on” — are few and small-scale for fermented foods.

Hutkins shared some research results. One study found that Korean elders who regularly consume kimchi harbor lactic acid bacteria (LAB) in their GI tract, providing compelling evidence that LAB survives digestion and reaches the gut. Another study of cultured dairy products, cheese, fermented vegetables, Asian fermented products and fermented drinks found that most contain over 10 million LAB per gram.

Still, the lack of credible studies is “a barrier we have to get past,” Hutkins says. There are confirmed health benefits with yogurt and kefir, but this research was funded by the dairy industry, a large trade group with significant resources.

“I think there’s enough evidence — most of it through these associated studies — to warrant this statement: fermented foods, including those that contain live microorganisms, should be included as part of a healthy diet.”

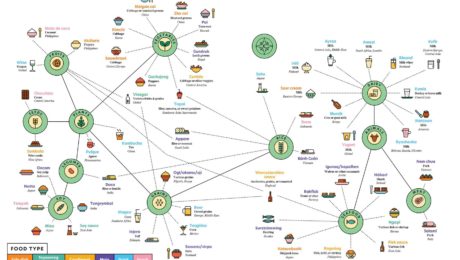

The World of Fermented Foods

In the latest issue of Popular Science, a creative infographic illustrates “the wonderful world of fermented foods on one delicious chart.” It represents “a sampling of the treats our species brines, brews, cures, and cultures around the world,” and is particularly interesting as it shows mainstream media catching on to fermentation’s renaissance. Fermentation fit with the issue’s theme of transformation in the wake of the pandemic.

Read more (Popular Science)

- Published in Food & Flavor

Keeping Traditional Fermentation Alive

Britt’s Fermented Foods is one of the only pickle companies in America still using oak barrel fermentation — how pickles were first fermented in ancient Egypt. But this method is often difficult and time-consuming, and many producers abandoned it in the 1970s when food regulation laws changed.

“The oak barrel has that ability to act as an agent in the fermentation,” says owner Britt Eustis. He explained to The Seattle Times that “the tannins in the oak barrels suppress the enzyme that naturally occurs and makes pickles turn soft,” keeping Britt’s pickles crisp.

Britt’s, with a warehouse on Whidbey Island in Washington, nearly shut down in 2019 due to mounting debt and production challenges. But a blueberry farm on the island offered to partner with the company, offering financial backing and helping to diversify income streams. Britt’s now sells kimchi and sauerkraut, also fermented in oak.

Read more (Seattle Times)

- Published in Business, Food & Flavor

Korean Flavors Hot in America in ‘21

Korean flavors are becoming more mainstream. Already popular with American diners is the Korean staple kimchi. But food experts predict two less common Korean favorites will soon become a part of American’s diets. Gochujang (fermented red pepper chili sauce) and doenjang-jigae (stew made with fermented soybean paste) will be 2021’s next food trend.

Read more (Forbes)

- Published in Food & Flavor

Kimchi Sales Exploding in Growth

Though kimchi only makes up 7% of the pickles and fermented vegetables category, sales are increasing at an explosive 90% growth rate. – SPINS

- Published in Business, Food & Flavor

Q&A with CEO of Atlantic Sea Farms

Atlantic Sea Farms began 2020 with landmark accomplishments. Their food service partnerships were bigger than ever, providing ready-cut kelp for David Chang’s kelp bowl created for Sweetgreen restaurants, seaweed kimchi for B.GOOD restaurant’s burgers and a kelp puree for salad dressing at Western Pennsylvania restaurant Lil’ Bit.

Then the coronavirus pandemic business shuttered restaurants, and Atlantic Sea Farms — which had sold 90% of their Maine kelp to food service establishments — had to flip their business model. Their new fermented products (Fermented Seaweed Salad, SeaChi, SeaKraut) and frozen Ready-Cut Kelp and Kelp Cubes became the focus of kelp processing. Atlantic Sea Farms will end 2020 processing 900,000 pounds of kelp and selling their retail product in 800 stores.

“People are excited about what we’re doing. We’re fermenting seaweed, and it tastes really damn good. We have retail buyers even at a time when every store is limiting SKUs, and they want our product,” says Brianna Warner, CEO of Atlantic Sea Farms. “The seaweed people typically eat in the United States is imported dry, rehydrated, then dyed with all the same chemicals that’s in Mountain Dew. But we are making a fermented seaweed that’s fresh, healthy and has all the goodness that comes from fermentation and kelp.”

Atlantic Sea Farms launched nine years ago as the first seaweed farm in the country. The majority (98%) of seaweed Americans eat is imported from Asia dried and unnaturally dyed. American-grown seaweed is still a new concept. When Warner became CEO two years ago, she set big goals for the small company. She wants Atlantic Sea Farms to provide alternative income sources for Maine’s lobster farmers, clean the water to aid climate change and make healthy food. They’ve increased the amount of kelp they produce to 14 times what they did two years ago and, by 2021, they will be in retail locations all over the U.S.

Coming on the heels of numerous awards for their one-of-a-kind, fermented kelp-based products, Warner spoke with TFA about Atlantic Sea Farms.

TFA: Tell me how your work at the Island Institute (Maine’s community sustainability non-profit) introduced you to Atlantic Sea Farms.

Briana Warner: At the time, Atlantic Sea Farms was called Ocean Approved and they were basically just a farming company. They were growing seeds and farming and I’m a development economist by trade. I was in the foreign service for a number of years before I moved to Maine. And the big question that the Island Institute was trying to solve and why they hired me as their first economic development director is we’re so dependent on this natural resource, which is lobster. It’s a lobster monoculture, we’re one of the most rural states in the country, we’re the oldest state in the country as far as demographics go, and there’s very little else in many of these communities other than lobster. There just is no diversity.

At the same time in Maine, we’ve had 10 of the best lobster farming years in the past 20 years. But that is worrying. Why? We know the Gulf of Maine is warming faster than 99% of oceans worldwide, and we know that’s because there’s arctic ice melt that’s creating a confluence of currents that gives the best opportunity for lobsters to thrive here. But what that ultimately means is it will continue to warm. And it will continue to warm to the point that lobsters are no longer surviving at the rate than they’re surviving now.

So with my economic development background, the ultimate solution is to provide alternative supplemental sources of income now while people have the money to invest in it. This is a way to absorb some of the shock of that lobster volatility so that in 10, 15, 20, 30, 40 years, whenever it is that lobster isn’t as secure as it is now. And it’s not secure now either — we know there will be lobsters now, we just don’t know where the price is, we don’t know where it will go, that’s some of the volatility, and all the eggs are in that basket.

The ultimate proof of concept is if we’re able to help people adapt to this kind of economic change and at the same time, mitigate some of its climate change effects. Because when you plant seaweed, you’re actually removing carbon and nitrogen from the water and reducing acidification locally. So it’s this incredible crop that’s off season to the lobster income.

I started working with fishermen to start getting them into seaweed, but the problem is there is no institutional buyers at scale in the entire country. We were the first commercial seaweed farm in the country, when I joined, they were just farming their own seaweed but not buying anything from anyone else. So we really had to think big about what could the supply chain look like? And how could we make this a viable alternative income for fishermen?

The answer to that is, first, make a good product that people want. Second, make sure that that money goes back to the fishermen. And that’s really what our entire business model is based around. Coming up with products that are really delicious, putting them out there in a way that’s accessible, because right now 98% of the seaweed that we eat in the United States is imported, Fresh seaweed is not something anyone has had in the United States. This is a totally different product from the very very cheap stuff that comes from Asia, and it’s a very clean product because it’s grown in the clean, cold waters of Maine by independent fishermen farmers. And it tastes good. Our supply chain that we’ve built from that narrative, we create all the seeds in house, we give them out to our farmers for free, then we guarantee purchase of every single blade of kep that they grow.

When someone is buying a jar of our Fermented Seaweed Salad, that money is going back quite literally into the pockets of fishermen because our whole supply chain is built around as much as we can sell, the more we can put in the water and buy. Then we can make the ocean cleaner, we can make the coast healthier from an economic perspective, and the products are really good for the consumer and taste good. So it’s sort of this five-legged stool that we’re constantly working towards.

TFA: How does kelp farming work?

BW: Our fishermen usually have four-acre farms, so you lease the water. You have to get a permit and a lease (from the state), which takes many months if not years. And we help them with all of that. We provide all the technical assistance for their site selection and leasing requirements. And then on four acres, they put two mooring balls at either end of about 1,000 foot of line, and they do this 13 times on the farm. They put it about 7-feet under water, so all you can see is mooring balls. They put it on these 1,000-foot, horizontal ropes and the kelp starts growing. Kelp grows up to 6-inches a day in the warmer summer months. So it really grows very quickly. We harvest what we call a baby kep because it’s so young. Because it’s at the top of the water column, its this incredibly high-quality food that allows us to serve it fresh in a way that wild harvest wouldn’t because wild harvest you don’t know if you’re getting a 4-year-old plant or an 8-year-old plant whereas, with us, we’re harvesting very young, very tender, very clean kelp that’s at top of the water column.

Right now, we work with 24 kelp farmers. It’s owner-operator run, they have the license to fish and own their own boat. Our farmers work lobster season from June to November, plant our kelp seeds in November and December, then start harvesting them in April. Kelp is the inverse of lobster season.

TFA: Atlantic Sea Farms was just a kelp farm when you joined the company two years ago. Why expand to commercial products?

BW: We were growing 30,000 pounds of kelp a year when I came on in 2018, and now our kelp farmers are growing 900,000 pounds of kelp a year. We rebranded and came out with all these products in 2019 because 30,000 pounds is such a small scale. Nobody is going to make money from doing that, especially farmers. If we really want to make an impact on the coast, there’s a sense of urgency to build this quickly and make sure that we get the scale that we need so we can actually help absorb some of that shock.

Most lobster in America is actually sold to restaurants. But with COVID, people had absolutely no idea what kind of season they were going into this year. It was terrifying. But we were able to send out an email before kelp harvest season saying “There’s a whole lot to worry about right now, but us picking up is not one of those things. We will be there and we will honor every commitment we have.” And it was not easy. It was very, very challenging. And we did it. Because we know above all else, integrity along this coast is what we’re built on and what we’re doing this for. So if we can’t do that, what are we doing? So we picked up, by the last dollar we had.

We were mostly working in food service, that’s why there was such a big fallout. But we had these fermented products that were used in some food service locations but were mostly part of our regional brand we were building in New England. We have our jars, we have our frozen products. They were just in the region. And we really just turned it on its head and went after buyers of national chains for retail and switched our food service to retail. We’ll be launching in Sprouts in January with our frozen products, we’re in several regions of Whole Foods already and we’ll be in more starting in April, we’re in MOMS, Wegmans, all these places where there are ferments. We feel very blessed and very lucky, we’ve been working our tails off. I can’t quite say it’s worked yet. We’ve got these placements, now we’ve got to slam these out. In June we were in 100 stores but by January, we’ll be in 800 stores.

TFA: What does Maine kelp taste like?

BW: It’s very fresh, very vegetal, very light. For our ready cut, for our cubes and for our fermented salad, We blanche it so it knocks off the sort of low-tide taste. That also gives it the green color because, when you dip seaweed in hot water, it turns bright green, so we don’t ever use any dyes or anything. For our SeaChi and our Sea-Beet Kraut, we use it raw because people want those kick-in-your face flavors. If you like kimchi, you’re not going to be afraid of a pretty hard umami taste. It makes our SeaChi so good to have that deep, ocean flavor on it that you’d usually have to use fish sauce for. The blanched seaweed really tastes super mild. It kind of takes on the flavor of whatever you put in it. It’s loaded with calcium, potassium and iodine.

TFA: Have you seen Americans’ perceptions of eating seaweed change? Do you think their perceptions of fermented food have changed, too?

BW: Absolutely. With seaweed, two of the top importers of seaweed are Trader Joes and Costco. People are eating it. There’s nori sheets everywhere and there’s sushi restaurants in the farthest reaches of America. It’s everywhere. People have definitely gotten a taste for seaweed. It’s new for Americans to have it in a form that’s not dried. People want to know where their food comes from, they want to know the food they are eating is regenerative, which is what kelp is, it’s taking carbon and nitrogen out of the water. We don’t use any arable land, we have no fertilizer, we have no fresh water, it’s like this climate change diet dream, everything in it is better for the environment. People also want to know the people connected to it — all our products have the faces of our farmers on it — it checks all those boxes. Let alone it tastes good and it’s good for you.

That’s similar with fermentation. Years ago, fermentation might have been ripe to have it on the menu, but quite frankly, everything out there wasn’t that good. It was these plastic bags of sauerkraut that tasted like pork and sauerkraut. There wasn’t anything else out there. Then you saw some kimchi coming out in the market that you didn’t really know what it said because there wasn’t a whole lot of English writing on it. Then the branding started coming and it started being in more food. For fermentation, it’s been a slow but obvious move because it’s good for you and, again, it tastes good. We just have to take the intimidation factor out, and I think fermentation did that already, and now we’re trying to do that with seaweed.

TFA: Why ferment seaweed?

BW: Part of it is that’s the best way to store it. But the other part of it, the Venn diagram between people who eat kimchi and people who are excited about beet kraut and fermented foods and those who aren’t intimidated at all by seaweed is pretty overlapping. There are few people who say “I like fermented food — but seaweed, ew.” The low hanging fruit is so substantial. That’s kind of our first folks we can approach, they can be our true believers and then they help us advocate for what we’re doing.

TFA: How much time did it take to perfect these recipes?

BW: I’d been playing with them for years. SeaChi was something I was doing — buying kimchi and putting our kelp in it. And the Sea-Beet Kraut came from the fact that beets and kelp really go well together, they’re both very sweet and ferment well together. We spent months trying to figure out how to not make that sugar turn it into a mess of purple explosion.

But we started working with this wonderful company called Chi Kitchen Foods based out of Rhode Island, and they make kimchi and vegan kimchi. So we basically took the recipes as far as we could take it, then we brought it to Minnie (Minnie Luong, founder Chi Kitchen Foods) and basically begged her to help us figure it out. Our speciality is in kelp. We do all the kelp, and then they make the kimchi. They basically helped us commercialize our fermented products.

TFA: Tell me about being a female CEO. Females often make the purchasing decisions for the home. What perspective do you bring to the table?

BW: On top of female CEO, female CEO in seafood. That’s been rarer. Seafood is a white male-dominated category. Most of the fishermen we work with are men — we have one woman.

We have an absolutely broken food system. Things don’t work. People aren’t making more money who are producing the food. The good food is not getting cheaper, and the bad food is getting cheaper. Food is one of the biggest polluters to our planet. Our priorities in what we eat and how to get the food to our table are completely off center and completely broken and creating a massive devastation both on our health and on the health of the environment.

This is not to slight my male counterparts, but that thinking happened under the leadership of men. So instead of taking the same thinking and trying to slightly adjust it, let’s absolutely rethink how we look at our food system. That’s going to take different minds, and it’s going to take different approaches. And I think women are in the best position to do that. We want to feed our children and we want to feed our planet. We look beyond five years in the future. Our plan is our grandchildren and the health of our families and the health of us. While that may be a vast generalization, I think we really need to look at who broke the system and how we can fix it. And that’s going to take all types of thinking.

TFA: Where do you see the future of fermented products?

BW: The future of fermented foods is wide open. We’ve seen, there’s been such a shift in the past year or two in branding, flavor. It used to be sort of this niche thing of a few sauerkrauts and kimchis that all varied in taste only slightly. Then everyone started doing a bunch of cool stuff with those products in their home kitchens or in restaurants. But you couldn’t find those cool things on the shelf. I think we’re starting to see people looking beyond cabbage and recognize that fermentation can happen in so many forms. Just like the homebrewers spurred craft brewers. People are realizing there’s a lot of innovation to be had and buyers are realizing the fermented category isn’t limited to just health food people anymore. It’s people who really want to get those probiotics but also the flavor of the fermentation in the first place. Kombucha has shown us that, obviously. There’s a lot of different forms of fermented stuff out there right now that people are going to simply because it says the word fermented. The possibilities, I think we’re just at the beginning.

- Published in Business, Food & Flavor