The Clash Over Kimchi

A Chinese tabloid has set off a social media war between China and South Korea. Global Times claimed China led the development of an international standard for paocai (pickled vegetables). Koreans said the claim was misleading because, in Chinese, paocai refers to kimchi, too. And kimchi is a fermented cabbage dish that is central to Korean cuisine.

Koreans are accusing the Chinese of cultural appropriation. “If China plagiarizes the fermentation process of kimchi in the future, then South Korea’s traditional culture may disappear.”

Read more (New York Times)

- Published in Food & Flavor

Retail Sales Trends for Fermented Food and Beverage

Kimchi, fermented sauces and tempeh are driving growth in the fermented food and beverage category, a $9.2 billion industry that’s grown 4% in the last year.

“We’re excited about the growth potential for fermented food. While fermented food represents about 1.4% of the market today, there are segments that are tracking well above the growth of food and beverage [overall] that are poised for disruption in the future,” says Perteet Spencer, vice president of strategic solutions at SPINS. Spencer shared this information in a recent webinar hosted by The Fermentation Association. “There’s a ton of opportunity to scale and increase the footprint of these products.”

SPINS spent weeks working with TFA to define the fermentation industry’s sales, drilling into 10 fermented product categories and 57 product types. Wine, beer and cheese sales were excluded from the data — those categories are very large, and would obscure trends in smaller categories. (All three are also well-represented by other organizations.)

Pickles and fermented vegetables “is a space that’s seen [a] pretty explosive uptick in growth over the past year,” Spencer says. Every segment is growing — kimchi, sauerkraut, beets, carrots, green beans, sliced and speared pickles and all other vegetables — with pickles the largest, nearly 60% of the category.

The biggest growth, though, is coming from products other than pickled cucumbers. Kimchi is at the center of numerous consumer retail trends. Consumers are purchasing healthier food made with fewer ingredients, and they want food with international flavors. Kimchi makes up only 7% of the category, but sales are increasing at an explosive 90% growth rate.

More people are experimenting with fermenting while they’re at home during the coronavirus pandemic, but these kitchen DIYers do not appear to be detracting from sales.

“The more people make fermented foods, they appreciate what’s available in the store that maybe didn’t exist five or 10 years ago,” notes Alex Lewin, author and TFA advisory board member who moderated the webinar. “Anyone who has made kimchi knows it takes a lot, it makes a big mess, you get red pepper powder stuck under your fingernails and onion in your eyes. I can make kimchi (at home), and then once I’ve made kimchi, I’m like ‘Ok, maybe next time I’ll buy it.’”

Fermented sauces are also growing, up 24% in 2020. The largest segment in sauces is, of course, soy sauce, almost 85% of the category. But gochujang, less than 2% of the category, is increasing at over a 56% growth rate.

Versatility is helping sauces, pickles and fermented vegetables, Spencer says. Any food product with multiple uses is selling well. The condiments and sauces can be used as a topping on eggs, hamburgers or pizza, or mixed-in a salad, rice dish or soup.

Sake, plant-based meat alternatives and miso had combined annual growth of $75 million in 2020. Sake grew 16%, and both plant-based meat alternatives and miso each grew 26%.

Yogurt and kombucha still dominate the fermented food and beverage market. Yogurt is 81% of the market; if yogurt is removed, kombucha is 51% of the remainder.. Both have experienced slowdowns in sales from their peaks. Kombucha sales have slowed recently, as grab-n-go opportunities have shrunk during the pandemic.

Yogurt giant brands Chobani, Yoplait and Dannon still dominate the category, as do GT Kombucha, Health-Ade and Kevita reign for kombucha.

Spencer notes the 4% growth rate of fermented products overall would be higher without yogurt. It’s a large category that — despite an uptick in 2020 during the pandemic – has been fairly flat in recent years. Core (traditional) yogurt has been growing at a 1.6% rate; Greek yogurt, at about twice that pace. Those two segments account for roughly 80% of the category.

“This is an opportunity for disruption for emerging brands,” Spencer says. “We’re already seeing some of the legacy segments start to get disrupted by new innovation, so I’m excited to see the evolution of that innovation and where that goes and kind of what opportunities peek out of that.”

“Overall, we’re seeing historically small segments gaining traction in the marketplace,” Spencer adds. “The pandemic has brought a renewed consumer focus on the fermented space.”

Though fermented products have an added healthy benefit, customers are looking for delicious flavor first.

“In these fermented categories we covered today, taste first is always really important. I think people are going to these categories for different taste experiences,” Spencer says. “If you can level up with a functional benefit, that’s fantastic, but we have to balance the taste first. If it’s highly functional but doesn’t taste good, it just doesn’t have the same success.”

- Published in Business

Fermentation as Metaphor: A Conversation

Fermentation is more than just a food processing technique. Sandor Katz, today’s “godfather of fermentation,” expounds on the metaphorical significance of fermentation in his new book “Fermentation as Metaphor.”

“Fermentation is such a fascinating lens through which to look at the world and the incredible practicality of traditional cultural wisdom,” says Katz, fermentation author and educator, during a webinar hosted by The Fermentation Association. “In the English language, there’s a long tradition of describing things as fermenting that are not foods and beverages. We talk about a period of great musical fermentation, artistic fermentation, political fermentation, culture fermentation, we’ve applied it very widely. This book is really an exploration of that and a reflection of that.”

Katz spoke with his friend Mara King, chef and food professional, and they shared thoughts on how fermentation can be an unstoppable force for change.

“Fermentation is really teaching the world to embrace weird and funky things,” King says. “Take natural wines as an example. There’s a big movement in the world of wine making for using older techniques, using less chemical filtration and clarification methods. What you’re left with is a product that changes year to year and a product that has subtle notes of animal or leather, things you wouldn’t find before. We’re realizing a little bit of horrible is quite wonderful.”

Until the 19th Century, all wine was natural, Katz points out. Winemakers relied on organisms on the skins of the grapes for the flavor. Beer used to be a similarly natural product, but that’s changed as brewers today add yeast strains.

“It’s so much more interesting and complex of a flavor than the mass-produced beer where just a single organism is introduced. Fermentation really encourages people to expand their palates,” Katz says. “Funk is good. Funk makes things interesting. Funk is complexity. What I’ve learned by working with fermented tofu in food, working with natto in food, working with sumbala, the West African condiments that are natto-like, working with fish sauce, is [these ingredients on their own] might taste awful to you, but a little bit can introduce this je ne sais quoi into the flavor of a dish. Complexity is good and even flavors on their own that people might find scary or intimidating.”

The photography featured in “Fermentation as Metaphor” is unique — magnified microbes used in the creation of fermented food and drink. The images, captured with a scanning electron microscope, show the complexity of these microorganisms. Each structure is supported by a smaller structure, with membranes that are highly permeable.

“There continues to be a magic to fermentation, maybe in some ways even more so as fewer people have direct contact with their food. As there’s less wine making, cheese making, [or] baking in our lives that people actually see, these processes become more and more mysterious. [Mystery] has always been an aspect of fermentation because, until very recent times, there was never a clear, rational scientific understanding of what is going on. They were always seen as divine processes with lots of ceremony and ritual attached to them,” Katz adds. “Fermentation takes this neutral, plain food and gives it this really discernable, compelling flavor.”

Katz is already working on his next book, a fermentation travelogue book highlighting what he’s learning about fermentation in his worldwide travels. Katz and King previously filmed a series “The People’s Republic of Fermentation,” sharing the fermentation traditions of southwest China. They were supposed to travel to Taiwan and eastern China earlier this year, but the trip was cancelled due to the coronavirus pandemic. Next on Katz’s “to do” list — exploring the fermented cuisine of West Africa.

For anyone interested in purchasing “Fermentation as Metaphor,” visit Amazon or Bookshop.

- Published in Food & Flavor

“All You Need Is Kimchi”

LA Times focused on kimchi in their October 4 food section entirely dedicated to the subject. Articles included a feature on kimchi making with Emily Kim @maangchi (the chef dubbed “YouTube’s Korean Julia Child”), must-try kimchi spots in the L.A. area and a history of kimchi in Korea. The article reads:

“A keystone of the Korean diet, kimchi is an unmistakable star that rarely commands the spotlight and is instead relegated to side-dish status. But its absence is always glaring.

“If I run out of kimchi, I’m lost,” said Emily Kim, better known to just about anyone who has ever searched online for a Korean recipe as Maangchi. For 13 years, Kim has helped bring Korean cooking into countless home kitchens through her cookbooks and her popular YouTube channel, Cooking Korean Food With Maangchi, which has nearly 5 million subscribers.

On days she prefers to keep it simple at home in the kitchen, Kim sticks to the basics: kimchi, rice and soup.

“Sometimes, depending on my mood, I’d make more protein, like bulgogi,” Kim said. But kimchi is the linchpin of her meals. “Even if I have meat and I can make bulgogi, if I don’t have kimchi, I’m like, ‘What should I eat?’”

Such is the fervent faith many Koreans have in their culture’s iconic dish. There’s a willingness to believe kimchi can save — be it a meal or the spirit — because it has come through so many times before.

“As long as I have kimchi in my refrigerator, I don’t worry much,” said Kim.”

Read more (Los Angeles Times)

- Published in Food & Flavor

Science Behind Fermented Vegetable Safety

Just because vegetables were fermented does not make them immune to harmful bacteria like E. coli. Though fermentation improves food safety, the quality of the raw vegetable before it’s fermented is extremely important.

“The issue of fermentation safety is one that comes up a lot. People are getting excited about the fermentation world these days, fermentation is increasing in popularity…(but) the wheels can fall off if you’re not careful,” says Fred Breidt, PhD, a USDA microbiologist. Breidt spoke during a recent webinar hosted by The Fermentation Association, “The Science Behind the Safety of Fermented Vegetables.” “The moral of the story: if the vegetables were safe to eat before you ferment them, they’re going to be safe to eat after you ferment them. If they’re not, you’ve got to ferment them for a long time to make sure they’re safe.”

An outbreak of dangerous bacteria in fermented vegetables, “it’s going to be pretty rare that that happens,” Breidt stresses. But, without proper sanitation protocol and vegetable quality control, pathogenic “bad guys” can flourish, like E. coli, salmonella and listeria. E. coli is more common in vegetables because it’s extremely acid resistant, and can survive for long periods of time at low pH levels and cold temperatures.

“Just washing the surface (of the vegetable) isn’t always going to do the trick,” Breidt says. “You don’t have to eat very much to get sick.”

An E. coli outbreak in kimchi made 230 Korean school children sick in 2013. The children, from seven different schools, all ate fermented kimchi made by the same manufacturer.

“If the folks had eaten the cabbage that this kimchi was made out of, they would have gotten sick as well,” Breidt says. “Was the cabbage improved in the sense of maybe it had fewer E. coli on it because of fermentation? Yes. But there was still enough when this was eaten to make a lot of people sick.”

“You can’t rely on salt for safety is the point,” he adds. “It does encourage the lactic acid bacteria and it helps them grow and it will increase overall the safety of your fermentation.”

David Ehreth, president and founder of Alexander Valley Gourmet, parent company of Sonoma Brinery, moderated the webinar. Ehreth first met Breidt when Sonoma Brinery made a few tons of sauerkraut that became infected with yeast. Ehreth says “I called Ghostbusters, and that’s Fred Breidt.” Though yeast is different from a pathogen like E. coli, Ehreth said Sonoma Brinery has managed to control yeast over the years by careful management of production techniques and improved sanitation methods.

- Published in Science

Sour Sells

American’s flavor choice of 2020: the funkier, the better. Fermentation reigns as sour becomes a selling point. A new article in Yahoo Life highlights fermented food and drink ancient roots and modern revival. A naturopathic doctor, kombucha brand leader, food influencer, wine shop owner and chef/owner of two Korean restaurants share their thoughts on why people love the “interesting and complicated” flavors of fermented food. Fermentation delivers on gut health benefits, is made with clean, unprocessed ingredients, preserves seasonal ingredients and “tells a story.”

The article continues: “They’re nuanced, many-layered. Kimchi and sourdough alike smack of acid and sour-sweet brine, even for those of us with less-than-refined palates. They taste like the process of aging. And while the wellness revolution would have us believe that fermented food’s uptick in popularity is merely a product of the fact that we’re eternally prepared to flirt with anything that just might make us feel better, the phenomenon cuts deeper than that. There’s something to be said for flavor that comes with a narrative — that tastes of its own timeline.”

Read more (Yahoo Life)

- Published in Food & Flavor

Study Links Low COVID Mortality to Fermented Veggies

A new study links lower COVID-19 deaths to countries where the diet is rich in fermented vegetables. Researchers in Europe found in countries where the national consumption of fermented vegetables is high, the mortality risk for COVID-19 decreased by 35.4%. Results are currently preliminary and undergoing peer review. But, if the hypothesis is confirmed, “COVID-19 will be the first infectious disease epidemic to involve biological mechanisms that are associated with a loss of ‘nature,'” reads an article in News Medical. “Significant changes in the microbiome caused by modern life and less fermented food consumption may have increased the spread or severity of the disease, (researchers) say.”

The study was led by Dr. Jean Bousquet, a professor of pulmonary medicine at Montpellier University in France. After researching that diet may play a big role in determining how well people can fight the coronavirus, Bousquet says he now eats fermented foods multiple times a week.

Read more (News Medical Life Sciences)

Kimchi is the New “It Girl” Pantry Staple

From the New York Times: “Outside Korea, it took at least 100 more years for kimchi to go from so-called spoiled stink to it-girl pantry staple and poster child for gut health. Today, some would say that it’s not just a cornerstone of Korean cuisine; it is Korea itself.” Kimchi, the article declares, is a verb. Kimchi is a traditional fermented cabbage dish, but encompasses “a much larger world of dishes you can find on any given Korean table.”

Read more (The New York Times)

- Published in Business, Food & Flavor

Q&A with Author and Fermentation Expert

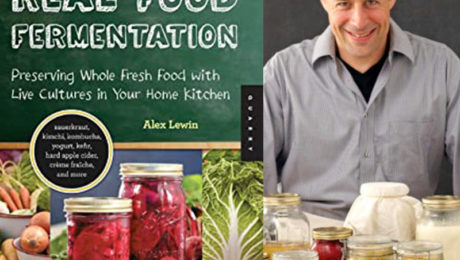

How to make fermentation practical for modern people? That’s a culinary goal Alex Lewin is passionate about reaching. Lewin is the author of “Real Food Fermentation” and “Kombucha, Kefir, and Beyond” (and member of TFA’s Advisory Board). His mission is “lowering barriers to fermentation.”

“Most of the ways we control the environment is lowering the barrier of fermentation for the microbes, like adding salt to the cabbage or keeping yogurt at the right temperature,” Lewin says. “But a lot of what I’m doing is lowering the barrier of fermentation for the humans.”

Lewin began fermenting as a hobby, and it turned into a passionate side career. Lewin works in the tech industry for his day job, then spends his spare time immersed in fermentation projects. His schedule parallels his interests. Lewin studied math at Harvard University, then studied cooking at the Cambridge School of Culinary Arts. He’s often tinkering with a microbe-rich condiment in the kitchen after office hours, and attending new fermentation conferences during his vacation time.

“Fermentation gives me direction in my life, but there’s also something about tech that nourishes me. And I don’t have to choose,” Lewin says. “The fermentation world, it is a huge amount of community. The community of fermenters really reflects the community of microbes. There’s some very interesting, very open-minded people who are outside of the mainstream in the fermentation world. And a lot of them feel they have a calling, that they were called to do this.”

Below, excerpts from a Q&A with Lewin from his home in California’s Bay Area:

The Fermentation Association: What got you first interested in fermentation?

Alex Lewin: I’d always been interested in food and started cooking a little in college. My dad had heart disease and later diabetes and he was on these diets and pills, but things didn’t seem to be getting him any better. When I got interested in health and nutrition during this time, I partly did it out of fear for my own life.

I started reading books about health, nutrition, diet, food. What struck me was they all said different things. I had studied math, physics, and generally the experts agree more or less on the obvious stuff. There’s discussion on the origin of the universe, yes, but no disagreement about what happens when you drop something and it hits the floor. I was surprised at the difference. One cookbook would say what would really matter in your health is your blood type — another would say the ratio from carbs to fat to protein that you eat, you have to eat them at a certain ratio at every meal. Then another book says don’t eat protein and carbs together, have space between them. I would read and was intrigued and frustrated. I had this idea that it should make sense and it didn’t make sense.

I was in a bookstore one day and I saw the book “The Revolution Will Not Be Microwaved” and thought it was such a fantastic title. It was about food politics and underground food movements and food subcultures. It was written by Sandor Katz and he writes with so much heart, very intelligently. He writes about radical food politics and has this way of keeping it very balanced and measured. Some books about radical politics can be shrill, but there’s nothing shrill or strident about anything Sandor does.

I wanted to read what else Sandor had written and found “Wild Fermentation,” and made my first jar of sauerkraut. In the meantime, there’s another book that affected me a lot, “Nourishing Traditions” by Sally Fallon. And that book similarly blew my mind. That book took all these diverse threads of diet, health and nutrition and pulled them all together in a way no other book has or has since. I felt like I finally understood what to eat, where before it was a free-for-all.

One of the things I learned to think about when you’re eating are foods with enzymes, microbes and live foods that weren’t processed with modern processing techniques. That really set me on my path.

TFA: After that, you spent the next decade diving into fermentation. You went to cooking school, started teaching fermentation classes, got involved with the Boston Public Market Association. How did your book “Real Food Fermentation” come about?

Lewin: A friend of mine who had a chocolate business recommended me to a book publisher. That was for “Real Food Fermentation,” my first book, in which I made it as easy as possible for people to ferment things. I knew from my class, making sauerkraut is not very complicated, and once people see it and how easy it is, they’re likely to keep doing it. So in my book, there are lots of pictures. There are lots of people with kitchen anxiety who are more comfortable if they see pictures of everything — pictures of me slicing the cabbage and putting it in the jar. I’m not a visual learner, I want to see words and measurements and numbers. So the book has both.

As time went on, I ended up meeting Raquel Guajardo (co-author for Lewin’s book “Kombucha, Kefir, and Beyond), and we decided to write a book about fermented drinks. I think it’s a great book because we both got a chance to share our ideas about food and health and what is happening in the world. Then we got to share recipes from my experience and her experience as a fermented drink producer in Mexico, where some of the pre-Hispanic traditions are very much alive.

Fermented drinks I think are also easier. They’re a little less weird to people than sauerkraut and kimchi, they’re less intimidating. We all drink things that are fizzy, sweet and sour. But like kimchi, it is so far outside of the usual experience of eating. Most people know they shouldn’t drink five Coca-Colas a day, so fermented drinks are the answer.

TFA: Tell me more about your goal to lower the barrier into fermentation.

Lewin: What is it about kombucha that is familiar? It’s fizzy, sweet and sour. What is soda? It’s fizzy, sweet and sour. I’m certainly not the first to observe that, but I’m connecting the dots on how we can integrate these ancient foods into our modern lives.

For me, I always considered myself an atheist. Then when I started fermenting, I started letting go and thinking there are things outside of our control and we just need to accept them. There are things we will never understand completely, there are forces we don’t even know about. I came to faith and spirituality through the practice of fermentation.

A lot of the problems that we face today have been created by application of high technology to the food system, then we try to solve them by using more food technology — like growing fake meat. The problems caused by high tech are not going to be solved by high tech, they’ll be solved by low tech. And fermentation is one of my favorite low tech technologies. You pretty much just need a knife.

Fermentation also gets away from the western, scientific, medical paradigm that’s so reductionist, where we’re looking for some small isolated problem in the body and then trying to counter it. Looking for some metabolic issue and trying to neutralize the symptoms. “Your blood pressure is high, let’s lower it with a pill.” If the underlying causes of all these things are eating bad food, trying to attack the symptoms one at a time is not the easiest way to make progress. We have to move away from this reductionist mindset where we’re playing whack-a-mole with our symptoms. We’re healthier looking for the underlying problems and addressing them.

Gut health is a big one. All sorts of other problems caused by high-tech, processed foods. Eastern medicine has more of an idea of holistic health, what’s going on in the system. I think that’s the future. I think a lot of the health problems will be solved through system-type thinking. This balance of energy. There’s a dynamic of equilibrium in our gut.

TFA: You mentioned Sandor Katz’ book “Wild Fermentation” introducing you to fermentation. What about his book appealed to you?

Lewin: There’s something rebellious about making food and leaving it out on the counter. I hadn’t been to cooking school yet at that point when I read it. But you read about food safety and there are rules, you can only leave food on the counter for so long at this temperature. There are all these things you’re not supposed to do with food. But in order to ferment, you have to violate these rules to grow the microbes. There’s something rebellious about fermentation.

Another part of it is the utterly low tech aspect to it. All the trouble we go to to process our food in high tech ways today, turns out we can do it better without preservatives, without heat packing things, without the refrigerator.

When you ferment something, every time it’s a little different. And you can keep doing it again and it doesn’t matter if it wasn’t perfect. And a lot of times you can do something interesting with it. I made pickles the other day, they turned out soft, so I’m going to make them into relish. Too much sourdough starter? Turn it into a porridge. Your kombucha got too sour? Turn it into vinegar. Sometimes something can be ruined, but often you can turn it into something else. Being able to make kombucha that’s better than most of the store-bought kombucha is pretty cool — I discovered that ability.

TFA: Why do you encourage people to incorporate fermented foods in their modern diet?

Lewin: One of them is just coming back to the kitchen. During the coronavirus pandemic, people are coming back to their kitchens. That’s an unqualifiedly good thing, it means that much less processed food and that much less fast food. Fermentation also brings people back into the kitchen. And fermentation is in the limelight during the pandemic. Especially sourdough right now. Fermented projects are great things to do with families, kids. When you talk to the older generation about making sourdough, pickles, bread, they have these stories. My mom never made pickles, but her father did. It’s not too late to get these stories. Food is one of the things that connects generations of people, that reminds us of our roots and grounds us, literally.

Making anything with your hands, it’s a cure for all sorts of things. Not even getting into physical, digestive health. Just making something and liking it is psychologically healthy. You feel empowered in the face of so many disempowering things. If you can turn cabbage into sauerkraut, you have power.

And then there are all the concrete, physical health benefits of eating fermented foods. You get more enzymes, more vitamins, more microbes, you get more of the good microbes and fewer of the bad microbes. You get probably less processed food, less sugar, you get all these trace substances that you really don’t get from processed food. Like nattokinase, which is this enzyme you only find in natto and might protect against heart disease and cancer. Depending on the ingredients you use when fermenting, if you use the right salt and right sweeteners, you can get minerals. Fermenting in some cases creates vitamins. You can straighten out a lot of digestive problems in my experience by introducing fermented foods, gradually.

TFA: You’ve watched Americans’ diets adapt (or not adapt) over the past few decades to changing health standards. How have Americans’ perception of fermented food and drink changed in that time?

Lewin: Americans are absolutely more accepting of it. The story of kombucha is a good one. You can follow annual kombucha sales. You used to say “kombucha” and people would say “Ew” or “What’s that?” or “My crazy aunt makes that.” Now, it’s a billion dollar business. You can get it in mainstream supermarkets in most of the country, it’s not a fringe thing anymore. Fermentation is coming to the mainstream. Kimchi is not a fringe thing. I think the rise of food culture, with food reality TV shows, has really helped fermented things like kimchi. When food trucks in LA started having kimchi and Korean BBQ tacos, for me I felt like something had turned the corner. The rise of microbreweries and the interest in natural wines and the movement away from like super-oaky chardonnays and ginormous reds to more natural wines. I think people are a lot more sophisticated about food than they were 20 years ago, and a lot of that is leading to increased interest in fermented foods.

Fermented foods are no longer fringe. We’ve come a long way in 20 years. Kombucha and kimchi are two of the flag bearers of fermentation. I think fermentation is on the rise. People will say “I think it’s just a fad,” and I’ll say “It’s absolutely not a fad.” People were fermenting 10,000 years ago. It never left. Every drop of alcohol you’re drinking, that’s fermented. It never went away, it was under the surface and now it’s on the surface again. People are just realizing it’s important.

TFA: Where do you see the future of the industry for fermented products?

Lewin: I think the more people ferment at home, the more people are going to want to buy fermented things. The more people ferment at home, the more they’ll appreciate fermented products and seek them out. It’s not like there’s a competition between home fermenting and commercial producers. If anything, there’s a symbiosis. I’ll make kimchi sometimes, but I’ll buy it sometimes, too, because it’s messy and there are people that make very good kimchi. Same with kombucha or high alcohol kombucha. I could make it if I wanted to, but it requires time and patience. Miso is another example, I don’t have the patience to wait six months to make miso.

- Published in Food & Flavor

Why are Sauerkraut and Kimchi Sales Up During the Pandemic?

People are turning to acidic dishes like sauerkraut and kimchi to protect themselves from the COVID-19 virus. Though there is no scientific evidence that foods like kimchi and sauerkraut will prevent spread of the virus, sales are booming. Health experts say it’s because cabbage is a superfood filled with antioxidants and vitamin C, and the fermented condiments are filled with probiotics that support the gut microbiome. Consumers are hypothesizing that coronavirus death rates in Germany and South Korea because sauerkraut and kimchi are traditional food staples in the two countries. In January, South Korea’s national health ministry issued a press release stressing that kimchi offers no protection against the virus. That hasn’t stopped Americans from buying it – sauerkraut sales surged 960% in March, while kimchi sales jumped 952% in February.

Doctors emphasize that the best way to prevent coronavirus infection is to avoid becoming exposed. Hand washing, social distancing and mask wearing are encouraged.

Read more (New York Post)