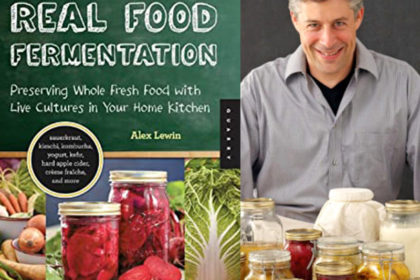

How to make fermentation practical for modern people? That’s a culinary goal Alex Lewin is passionate about reaching. Lewin is the author of “Real Food Fermentation” and “Kombucha, Kefir, and Beyond” (and member of TFA’s Advisory Board). His mission is “lowering barriers to fermentation.”

“Most of the ways we control the environment is lowering the barrier of fermentation for the microbes, like adding salt to the cabbage or keeping yogurt at the right temperature,” Lewin says. “But a lot of what I’m doing is lowering the barrier of fermentation for the humans.”

Lewin began fermenting as a hobby, and it turned into a passionate side career. Lewin works in the tech industry for his day job, then spends his spare time immersed in fermentation projects. His schedule parallels his interests. Lewin studied math at Harvard University, then studied cooking at the Cambridge School of Culinary Arts. He’s often tinkering with a microbe-rich condiment in the kitchen after office hours, and attending new fermentation conferences during his vacation time.

“Fermentation gives me direction in my life, but there’s also something about tech that nourishes me. And I don’t have to choose,” Lewin says. “The fermentation world, it is a huge amount of community. The community of fermenters really reflects the community of microbes. There’s some very interesting, very open-minded people who are outside of the mainstream in the fermentation world. And a lot of them feel they have a calling, that they were called to do this.”

Below, excerpts from a Q&A with Lewin from his home in California’s Bay Area:

The Fermentation Association: What got you first interested in fermentation?

Alex Lewin: I’d always been interested in food and started cooking a little in college. My dad had heart disease and later diabetes and he was on these diets and pills, but things didn’t seem to be getting him any better. When I got interested in health and nutrition during this time, I partly did it out of fear for my own life.

I started reading books about health, nutrition, diet, food. What struck me was they all said different things. I had studied math, physics, and generally the experts agree more or less on the obvious stuff. There’s discussion on the origin of the universe, yes, but no disagreement about what happens when you drop something and it hits the floor. I was surprised at the difference. One cookbook would say what would really matter in your health is your blood type — another would say the ratio from carbs to fat to protein that you eat, you have to eat them at a certain ratio at every meal. Then another book says don’t eat protein and carbs together, have space between them. I would read and was intrigued and frustrated. I had this idea that it should make sense and it didn’t make sense.

I was in a bookstore one day and I saw the book “The Revolution Will Not Be Microwaved” and thought it was such a fantastic title. It was about food politics and underground food movements and food subcultures. It was written by Sandor Katz and he writes with so much heart, very intelligently. He writes about radical food politics and has this way of keeping it very balanced and measured. Some books about radical politics can be shrill, but there’s nothing shrill or strident about anything Sandor does.

I wanted to read what else Sandor had written and found “Wild Fermentation,” and made my first jar of sauerkraut. In the meantime, there’s another book that affected me a lot, “Nourishing Traditions” by Sally Fallon. And that book similarly blew my mind. That book took all these diverse threads of diet, health and nutrition and pulled them all together in a way no other book has or has since. I felt like I finally understood what to eat, where before it was a free-for-all.

One of the things I learned to think about when you’re eating are foods with enzymes, microbes and live foods that weren’t processed with modern processing techniques. That really set me on my path.

TFA: After that, you spent the next decade diving into fermentation. You went to cooking school, started teaching fermentation classes, got involved with the Boston Public Market Association. How did your book “Real Food Fermentation” come about?

Lewin: A friend of mine who had a chocolate business recommended me to a book publisher. That was for “Real Food Fermentation,” my first book, in which I made it as easy as possible for people to ferment things. I knew from my class, making sauerkraut is not very complicated, and once people see it and how easy it is, they’re likely to keep doing it. So in my book, there are lots of pictures. There are lots of people with kitchen anxiety who are more comfortable if they see pictures of everything — pictures of me slicing the cabbage and putting it in the jar. I’m not a visual learner, I want to see words and measurements and numbers. So the book has both.

As time went on, I ended up meeting Raquel Guajardo (co-author for Lewin’s book “Kombucha, Kefir, and Beyond), and we decided to write a book about fermented drinks. I think it’s a great book because we both got a chance to share our ideas about food and health and what is happening in the world. Then we got to share recipes from my experience and her experience as a fermented drink producer in Mexico, where some of the pre-Hispanic traditions are very much alive.

Fermented drinks I think are also easier. They’re a little less weird to people than sauerkraut and kimchi, they’re less intimidating. We all drink things that are fizzy, sweet and sour. But like kimchi, it is so far outside of the usual experience of eating. Most people know they shouldn’t drink five Coca-Colas a day, so fermented drinks are the answer.

TFA: Tell me more about your goal to lower the barrier into fermentation.

Lewin: What is it about kombucha that is familiar? It’s fizzy, sweet and sour. What is soda? It’s fizzy, sweet and sour. I’m certainly not the first to observe that, but I’m connecting the dots on how we can integrate these ancient foods into our modern lives.

For me, I always considered myself an atheist. Then when I started fermenting, I started letting go and thinking there are things outside of our control and we just need to accept them. There are things we will never understand completely, there are forces we don’t even know about. I came to faith and spirituality through the practice of fermentation.

A lot of the problems that we face today have been created by application of high technology to the food system, then we try to solve them by using more food technology — like growing fake meat. The problems caused by high tech are not going to be solved by high tech, they’ll be solved by low tech. And fermentation is one of my favorite low tech technologies. You pretty much just need a knife.

Fermentation also gets away from the western, scientific, medical paradigm that’s so reductionist, where we’re looking for some small isolated problem in the body and then trying to counter it. Looking for some metabolic issue and trying to neutralize the symptoms. “Your blood pressure is high, let’s lower it with a pill.” If the underlying causes of all these things are eating bad food, trying to attack the symptoms one at a time is not the easiest way to make progress. We have to move away from this reductionist mindset where we’re playing whack-a-mole with our symptoms. We’re healthier looking for the underlying problems and addressing them.

Gut health is a big one. All sorts of other problems caused by high-tech, processed foods. Eastern medicine has more of an idea of holistic health, what’s going on in the system. I think that’s the future. I think a lot of the health problems will be solved through system-type thinking. This balance of energy. There’s a dynamic of equilibrium in our gut.

TFA: You mentioned Sandor Katz’ book “Wild Fermentation” introducing you to fermentation. What about his book appealed to you?

Lewin: There’s something rebellious about making food and leaving it out on the counter. I hadn’t been to cooking school yet at that point when I read it. But you read about food safety and there are rules, you can only leave food on the counter for so long at this temperature. There are all these things you’re not supposed to do with food. But in order to ferment, you have to violate these rules to grow the microbes. There’s something rebellious about fermentation.

Another part of it is the utterly low tech aspect to it. All the trouble we go to to process our food in high tech ways today, turns out we can do it better without preservatives, without heat packing things, without the refrigerator.

When you ferment something, every time it’s a little different. And you can keep doing it again and it doesn’t matter if it wasn’t perfect. And a lot of times you can do something interesting with it. I made pickles the other day, they turned out soft, so I’m going to make them into relish. Too much sourdough starter? Turn it into a porridge. Your kombucha got too sour? Turn it into vinegar. Sometimes something can be ruined, but often you can turn it into something else. Being able to make kombucha that’s better than most of the store-bought kombucha is pretty cool — I discovered that ability.

TFA: Why do you encourage people to incorporate fermented foods in their modern diet?

Lewin: One of them is just coming back to the kitchen. During the coronavirus pandemic, people are coming back to their kitchens. That’s an unqualifiedly good thing, it means that much less processed food and that much less fast food. Fermentation also brings people back into the kitchen. And fermentation is in the limelight during the pandemic. Especially sourdough right now. Fermented projects are great things to do with families, kids. When you talk to the older generation about making sourdough, pickles, bread, they have these stories. My mom never made pickles, but her father did. It’s not too late to get these stories. Food is one of the things that connects generations of people, that reminds us of our roots and grounds us, literally.

Making anything with your hands, it’s a cure for all sorts of things. Not even getting into physical, digestive health. Just making something and liking it is psychologically healthy. You feel empowered in the face of so many disempowering things. If you can turn cabbage into sauerkraut, you have power.

And then there are all the concrete, physical health benefits of eating fermented foods. You get more enzymes, more vitamins, more microbes, you get more of the good microbes and fewer of the bad microbes. You get probably less processed food, less sugar, you get all these trace substances that you really don’t get from processed food. Like nattokinase, which is this enzyme you only find in natto and might protect against heart disease and cancer. Depending on the ingredients you use when fermenting, if you use the right salt and right sweeteners, you can get minerals. Fermenting in some cases creates vitamins. You can straighten out a lot of digestive problems in my experience by introducing fermented foods, gradually.

TFA: You’ve watched Americans’ diets adapt (or not adapt) over the past few decades to changing health standards. How have Americans’ perception of fermented food and drink changed in that time?

Lewin: Americans are absolutely more accepting of it. The story of kombucha is a good one. You can follow annual kombucha sales. You used to say “kombucha” and people would say “Ew” or “What’s that?” or “My crazy aunt makes that.” Now, it’s a billion dollar business. You can get it in mainstream supermarkets in most of the country, it’s not a fringe thing anymore. Fermentation is coming to the mainstream. Kimchi is not a fringe thing. I think the rise of food culture, with food reality TV shows, has really helped fermented things like kimchi. When food trucks in LA started having kimchi and Korean BBQ tacos, for me I felt like something had turned the corner. The rise of microbreweries and the interest in natural wines and the movement away from like super-oaky chardonnays and ginormous reds to more natural wines. I think people are a lot more sophisticated about food than they were 20 years ago, and a lot of that is leading to increased interest in fermented foods.

Fermented foods are no longer fringe. We’ve come a long way in 20 years. Kombucha and kimchi are two of the flag bearers of fermentation. I think fermentation is on the rise. People will say “I think it’s just a fad,” and I’ll say “It’s absolutely not a fad.” People were fermenting 10,000 years ago. It never left. Every drop of alcohol you’re drinking, that’s fermented. It never went away, it was under the surface and now it’s on the surface again. People are just realizing it’s important.

TFA: Where do you see the future of the industry for fermented products?

Lewin: I think the more people ferment at home, the more people are going to want to buy fermented things. The more people ferment at home, the more they’ll appreciate fermented products and seek them out. It’s not like there’s a competition between home fermenting and commercial producers. If anything, there’s a symbiosis. I’ll make kimchi sometimes, but I’ll buy it sometimes, too, because it’s messy and there are people that make very good kimchi. Same with kombucha or high alcohol kombucha. I could make it if I wanted to, but it requires time and patience. Miso is another example, I don’t have the patience to wait six months to make miso.