The Rise of Fermented Foods and -Biotics

Microbes on our bodies outnumber our human cells. Can we improve our health using microbes?

“(Humans) are minuscule compared to the genetic content of our microbiomes,” says Maria Marco, PhD, professor of food science at the University of California, Davis (and a TFA Advisory Board Member). “We now have a much better handle that microbes are good for us.”

Marco was a featured speaker at an Institute for the Advancement of Food and Nutrition Sciences (IAFNS) webinar, “What’s What?! Probiotics, Postbiotics, Prebiotics, Synbiotics and Fermented Foods.” Also speaking was Karen Scott, PhD, professor at University of Aberdeen, Scotland, and co-director of the university’s Centre for Bacteria in Health and Disease.

While probiotic-containing foods and supplements have been around for decades – or, in the case of fermented foods, tens of thousands of years – they have become more common recently . But “as the terms relevant to this space proliferate, so does confusion,” states IAFNS.

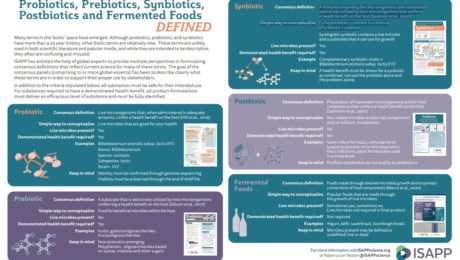

Using definitions created by the International Scientific Association for Postbiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP), Marco and Scott presented the attributes of fermented foods, probiotics, prebiotics, synbiotics and postbiotics.

The majority of microbes in the human body are in the digestive tract, Marco notes: “We have frankly very few ways we can direct them towards what we need for sustaining our health and well being.” Humans can’t control age or genetics and have little impact over environmental factors.

What we can control, though, are the kinds of foods, beverages and supplements we consume.

Fermented Foods

It’s estimated that one third of the human diet globally is made up of fermented foods. But this is a diverse category that shares one common element: “Fermented foods are made by microbes,” Marco adds. “You can’t have a fermented food without a microbe.”

This distinction separates true fermented foods from those that look fermented but don’t have microbes involved. Quick pickles or cucumbers soaked in a vinegar brine, for example, are not fermented. And there are fermented foods that originally contained live microbes, but where those microbes are killed during production — in sourdough bread, shelf-stable pickles and veggies, sausage, soy sauce, vinegar, wine, most beers, coffee and chocolate. Fermented foods that contain live, viable microbes include yogurt, kefir, most cheeses, natto, tempeh, kimchi, dry fermented sausages, most kombuchas and some beers.

“There’s confusion among scientists and the public about what is a fermented food,” Marco says.

Fermented foods provide health benefits by transforming food ingredients, synthesizing nutrients and providing live microbes.There is some evidence they aid digestive health (kefir, sourdough), improve mood and behavior (wine, beer, coffee), reduce inflammatory bowel syndrome (sauerkraut, sourdough), aid weight loss and fight obesity (yogurt, kimchi), and enhance immunity (kimchi, yogurt), bone health (yogurt, kefir, natto) and the cardiovascular system (yogurt, cheese, coffee, wine, beer, vinegar). But there are only a few studies on humans that have examined these topics. More studies of fermented foods are needed to document and prove these benefits.

Probiotics

Probiotics, on the other hand, have clinical evidence documenting their health benefits. “We know probiotics improve human health,” Marco says.

The concept of probiotics dates back to the early 20th century, but the word “probiotic” has now become a household term. Most scientific studies involving probiotics look at their benefit to the digestive tract, but new research is examining their impact on the respiratory system and in aiding vaginal health.

Probiotics are different from fermented foods because they are defined at the strain level and their genomic sequence is known, Marco adds. Probiotics should be alive at the time of consumption in order to provide a health benefit.

Postbiotics

Postbiotics are dead microorganisms. It is a relatively new term — also referred to as parabiotics, non-viable probiotics, heat-killed probiotics and tyndallized probiotics — and there’s emerging research around the health benefits of consuming these inanimate cells.

“I think we’ll be seeing a lot more attention to this concept as we begin to understand how probiotics work and gut microbiomes work and the specific compounds needed to modulate our health,” according to Marco.

Prebiotics

Prebiotics are, according to ISAPP, “A substrate selectively utilized by host microorganisms conferring a health benefit on the host.”

“It basically means a food source for microorganisms that live in or on a source,” Scott says. “But any candidate for a prebiotic must confer a health benefit.”

Prebiotics are not processed in the small intestine. They reach the large intestine undigested, where they serve as nutrients for beneficial microorganisms in our gut microbiome.

Synbiotics

Synbiotics are mixtures of probiotics and prebiotics and stimulate a host’s resident bacteria. They are composed of live microorganisms and substrates that demonstrate a health benefit when combined.

Scott notes that, in human trials with probiotics, none of the currently recognized probiotic species (like lactobacilli and bifidobacteria) appear in fecal samples existing probiotics.

“There must be something missing in what we’re doing in this field,” she says. “We need new probiotics. I’m not saying existing probiotics don’t work or we shouldn’t use them. But I think that now that we have the potential to develop new probiotics, they might be even better than what we have now.”

She sees great potential in this new class of -biotics.

Both Scott and Marco encouraged nutritionists to work with clients on first improving their diets before adding supplements. The -biotics stimulate what’s in the gut, so a diverse diet is the best starting point.

The Regulatory Landscape

Collaboration with regulators, not confrontation, is the recommended course of action for fermenters, experts suggest.

“Producers are speaking one language and regulators are speaking another,” says Abigail Snyder, assistant professor of microbial food safety at Cornell University. “Producers are like ‘Hey, this has been produced forever and it has a history of safe production!’ That’s not super meaningful for regulators. Regulators are used to this codified framework that is not necessarily built around fermented foods. There’s a middle ground.”

Snyder spoke with a panel of experts on health and safety regulations during TFA’s conference, FERMENTATION 2021. The consensus: food regulations exist to protect the consumer, but complying with myriad national, state and local laws can be difficult and frustrating to navigate, especially for a fermented food or beverage that utilizes novel food processes.

“Don’t be afraid, don’t feel like you’re going to tick off the inspector,” says Adam Inman, assistant program manager for the Kansas Department of Agriculture Food Safety & Lodging Program. He advises producers to always ask regulators for help. “Even if we start with your recipe and your process and we just document that, that can go a long way as a starting point.”

Jonathan Wheeler, coordinator for special processes at retail for the South Carolina Department of Health & Environmental Control, says if you’re dealing with a regulator unfamiliar with fermentation, ask for a supervisor. Wheeler manages South Carolina’s team of 80-90 regulators and points out that a health inspection should be an education opportunity for the regulator, too.

“We are partners on the same team, just in different roles,” Wheeler says. “Our approach in South Carolina has been driven by the need to educate as well as regulate. You have a voice, it’s part of collaboration and inspectors…are open to input [from producers].”

Still, compliance is not without its challenges.

Soirée-Leone, writer, homesteader and local food advocate, says that food inspection is one of the biggest challenges for smaller producers — especially in rural areas, where resources can be limited. For example, in Tennessee where she lives, home-based food businesses can sell their goods at farmers markets, as long as those items don’t need to be refrigerated. But there’s no rule for food that needs to be frozen,, so producers are allowed by the health department to sell popsicles.

“It’s very challenging, and a lot of people get very frustrated in the process,” she says.

Erin Leigh DiCaprio, assistant professor of cooperative extension at University of California, Davis, notes that regulations differ from state to state — a ferment produced under cottage food laws in one state could need a processed food license in another. She points out every state or county has an extension educator like herself who has the needed technical expertise to work with producers and regulators. DiCaprio specifically works with smaller-scale processors to navigate regulations in California.

Could the U.S. learn from other countries?In Korea, Japan and China, fermented foods and drinks are common, yet regulations are minimal.

“There’s a cultural aspect there… not necessarily advocating eliminating regulations but saying that a culture — and no pun intended in this case — but a culture that’s been used to eating fermented foods for years and had no negative impact. Is there some education to be learned from that?” questions Neal Vitale, the moderator and executive director of TFA.

“We should not be as regulators in a position of trying to jam fermentation processes… into a mold where they all look the same — because they don’t,” Wheeler says. “Educate me as how you want that process to look.”

- Published in Business

How Do Alternative Proteins Overcome Their Challenges?

Is carbon the real villain in modern diets? One-third of greenhouse gas emissions come from food production, so companies are turning to technologies like precision fermentation and cell-cultured meat to help create a more sustainable industry. But a transition to alternative proteins won’t be easy.

“The food tech industry has a blind spot,” says John Fasman, U.S. digital editor with The Economist, “they haven’t fully grappled with the fact that food isn’t just fuel, it’s an emotional connection to a lot of people.”

The Economist’s latest cover piece — “Future Food” — explores if and how first-world food systems may adapt. Fasman (who wrote the piece) and Josie Delap (The Economist’s international editor) discussed the business and ethics of alternative proteins in a webinar.

The Conceptual Hurdle of Alt Meat

Though many consumers are adopting flexitarian diets, widespread change isn’t realistic. “Getting people to adjust to their culture expectations of food is a very long task,” Delap adds.

For example, the Thanksgiving turkey or Christmas ham is a holiday tradition consumers aren’t eager to change — and meat substitutes cannot yet deliver. Alternative proteins have come light years from early days of vegetarian “meat” — which was often a flavorless mash of beans and lentils — and now include flavorful and appealing ground meat products. But no one is producing an entire alternative turkey or steak, in which fat, muscle and sinew are layered together.

According to the Good Food Institute, alternative proteins are made by one of three food technologies:

- Plant-based is the oldest form of meat alternatives, using plants to recreate meat flavors.

- Cultivated meat is produced directly from the cells of animals. Muscle cells are taken from a living animal, then multiplied in a lab to create a meat product biologically identical to meat tissue.

- Fermented alternative proteins are made using one of three processes: traditional fermentation (the ancient practice of using microbes in food), biomass fermentation (growing naturally occurring, protein-dense, fast-growing organisms, like fungi or algae) or precision fermentation (uses microbial hosts as “cell factories” to produce specific ingredients.)

“The most striking thing for me as a non-scientist is the extent to which what we eat can be broken into chemical elements and then replicated,” Fasman says. “Replicas of meat look and cook and smell strikingly like meat. You can enhance the flavor through fermentation.”

Consumers have been conditioned to believe foods with too many ingredients are worse for you. Alternative foods create new possibilities — they are built from the ground up, tweaked for nutritional content and made better with supplements. But consumers will have to accept engineered food in order to make a positive environmental impact.

“If you’re going to change the system you’re going to have to reckon with processing at some point and the question is how do you make processing as healthy as possible,” Fasman adds.

Competing on Price

Price is another challenge for alternative proteins. Today, they are often more expensive than meat.

“The risk is that they become a way for middle class and wealthy diners in rich countries to make choices that let them feel good about themselves as opposed to something that really transforms the world’s food system,” Fasman says. “It’s going to be hard for them to compete on price. I don’t think there’s any way around this problem.”

Fasman says the alternative protein industry is at the first stage of a very long process that is made longer by scaling, supply chain, acceptance and regulatory challenges. He estimates it will take at least a decade for alt proteins to compete with meat.

“[Alt-meats] will only be affordable at scale. And that’s why this period right now is the linchpin and it’s so tricky,” Fasman says. Startup companies are operating out of small labs. None of them — outside of Beyond Meat, creator of the Impossible Burger) — is big enough to satisfy a national, or even regional, market. But larger meat companies, like Tyson, Cargill or JBS, have also created meatless products.

Worldwide Adoption

Alternative meat’s acceptance on a global stage is even farther away, agreed Fasman and Delap. Animal-based meat is cheaper in richer countries, and often considered a status symbol or a special occasion dish.

“Burgers are a choice people in middle class cities can make,” Delap says.

Fasman adds that, while it’s unrealistic to think of alt meat being adopted broadly in the short term, it’s a start to offsetting the dangerous greenhouse gas emissions associated with the production of meat.

“Cultured meat, plant-based meat and milk substitutes are in their infancy. You want to scale up where the money and market is,” he says. “There’s a reason to start this process in wealthy countries and then have it flow to the rest of the world from there.”

- Published in Business, Food & Flavor

Definition & History of Fermentation

“Human civilization simply would not have been possible without fermented foods and beverages…we’re here today because fermented foods have been popular for humans for at least 10,000 years,” says Bob Hutkins, professor of food science at the University of Nebraska (and a recent addition to TFA’s Advisory Board).

Hutkins was the opening keynote speaker at FERMENTATION 2021, The Fermentation Association’s first international conference. His presentation explored the history, definition and health benefits of fermented foods.

Cultured History

The topic of fermentation extends to evolution, archaeology, science and even the larger food industry.

“The discipline of microbiology began with fermentation, all the early microbiologists studied fermentation,” Hutkins says.

Louis Pasteur patented his eponymous process, developed to improve the quality of wine at Napoleon III’s request. The microbes studied back then — lactococcus, lactobacillus and saccharomyces — remain the most studied strains.

“What interested those early microbiologists — namely how to improve food and beverage fermentation, how to improve their productivity, their nutrition — are the very same things that interest 21st century fermentation scientists,” Hutkins says.

Hutkins is the author of one of the books considered gospel in the industry, “Microbiology and Technology of Fermented Foods.” He says that fermented foods defined the food industry. In its early days, it was small-scale, traditional food production that “we call a craft industry now.” At the time, food safety wasn’t recognized as a microbiological problem.

Today’s modern food industry manufactures on a large-scale in high throughput factories withmany automated processes. Food safety is a priority and highly regulated. And, thanks to developments in gene sequencing, many fermented products are made with starter cultures selected for their individual traits.

“But I would say that there’s been kind of a merging between these traditional and modern approaches to manufacturing fermented foods, where we’re all concerned about time sensitivity, excluding contaminants, making sure that we have consistent quality, safety is a vital concern and extensive culture knowledge,” Hutkins says.

Defining & Demystifying

Fermentation — “the original shelf-life foods” — is experiencing a major moment. “Fermented foods in 2021 check all the topics” of popular food genres: artisanal, local, organic, natural, healthy, flavorful, sustainable, entrepreneurial, innovative, hip and holistic. “They continue to be one of the most popular food categories,” Hutkins continues.

Interest in fermentation is reaching beyond scientists, to nutritionists and clinicians. But Hutkins says he’s still surprised to learn how many professionals don’t understand fermentation. To address the confusion, a panel of interdisciplinary scientists created a global definition of fermented foods in March 2021.

“Fermentation was defined with these kind of geeky terms that I don’t know that they mean very much to anybody,” he says.

The textbook biochemical definition of fermentation that a microbiologist learns in Biochemistry 101 doesn’t work for a nutritionist or clinician focusing on fermentation’s health benefits. The panel, which spent a year coming to a consensus, wanted a definition that would simply illustrate “raw food being converted by microbes into a fermented food.” The new definition, published in the the journal Nature and released in conjunction with the International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP), reads: “Foods made through desired microbial growth and enzymatic conversions of food components.”

Fermentation in 2022

Hutkins predicts 2022 will see more studies addressing whether there are clinical health benefits from eating fermented foods. The groundbreaking study on fermented foods at Stanford was important. It found that a diet high in fermented foods increases microbiome diversity, lowers inflammation, and improves immune response. But research like this is expensive, so randomized control trials are few.

Fermented foods could also make their way into dietary guidelines.

“Fermented foods, including those that contain live microbes, should be included as part of a healthy diet,” Hutkins says.

- Published in Food & Flavor, Science

Fermentation in Anthropology

Fermented foods have had an impact on human evolution, and they continue to affect social dynamics, according to a new collection of 16 studies in the journal Current Anthropology. This research explores how “microbes are the unseen and often overlooked figures that have profoundly shaped human culture and influenced the course of human history.”

The journal’s special edition, Cultures of Fermentation, features work from multiple disciplines: microbiology, cultural anthropology, archaeology and biological anthropology. Researchers were based all over the globe.

“Humans have a deep and complex relationship with microbes, but until recently this history has remained largely inaccessible and mostly ignored within anthropology,” reads the introduction, Cultures of Fermentation: Living with Microbes. “Fermentation is at the core of food traditions around the world, and the study of fermentation crosscuts the social and natural sciences.”

The impetus for the articles was a 2019 symposium organized by the non-profit Wenner-Gren Foundation. This organization aims to bring together scholars to debate and discuss topics in anthropology.

“Fermentation is at the core of food traditions around the world, and the study of fermentation crosscuts the social and natural sciences,” the introduction continues. The aim of the symposium and corresponding research was to “foster interdisciplinary conversations integral to understanding human-microbial cultures. By bridging the fields of archaeology, cultural anthropology, biological anthropology, microbiology, and ecology, this symposium will cultivate an anthropology of fermentation.”

Here is a listing the included studies:

- Predigestion as an Evolutionary Impetus for Human Use of Fermented Food (Katherine R. Amato,Elizabeth K. Mallott, Paula D’Almeida Maia, and Maria Luisa Savo Sardaro). Using research on nonhuman primates, researchers conclude that “fermentation played a central role in enabling our earliest ancestors to survive in the forested grasslands in Africa where key anatomical features of our species emerged. Fermentation occurs spontaneously in nature. Most nonhuman primates cannot metabolize fermented products, but humans evolved the capacity to use them as fuel. …By breaking down tough and toxic plant species, fermentation helped humans meet the caloric requirements associated with their growing brains and shrinking guts. These anatomical changes both stemmed from and fueled the emergence of collective forms of know-how — microbial and human cultures fed on one another, in this view of the human past.”

- Toward a Global Ecology of Fermented Foods (Robert R. Dunn, John Wilson, Lauren M. Nichols, and Michael C. Gavin). This ecological view of fermentation maps the “emergence and divergence of the world’s many varieties of fermented foods.”

- Prehistoric Fermentation, Delayed-Return Economies, and the Adoption of Pottery Technology (Oliver E. Craig). Craig explores the central role of pottery in “people’s ability to amass the kinds of surpluses that allowed human communities to lay down roots.” Pots were ideal as the storage vessels that made it possible to domesticate microbes.

- Seeking Prehistoric Fermented Food in Japan and Korea (Shinya Shoda). This study focuses on fermentation’s rise in prehistoric Japan and Korea along with each country’s respective cultural achievements.

- Cultured Milk: Fermented Dairy Foods along the Southwest Asian–European Neolithic Trajectory (Eva Rosenstock, Julia Ebert, and Alisa Scheibner). Using archaeological evidence of fermentation, researchers track the “emergence of lactase persistence in sites where dairying made an early appearance. It appears that people ate cheese and yoghurt well before they drank milk: only a small subsection of the human population retains the enzymes needed to digest lactose into adulthood.”

- Missing Microbes and Other Gendered Microbiopolitics in Bovine Fermentation (Megan Tracy). Industrial dairy farms are finding “missing microbes” in cows, Tracy highlights in her study. Newborn calves are separated from their mothers in industrialized dairy farms, and thereby lose the critical gut connections that would have been made by drinking breast milk.

- Living Machines Go Wild: Policing the Imaginative Horizons of Synthetic Biology (Eben Kirksey). Kirksey profiles the International Genetically Engineered Machine competition in Boston, where living creatures made through genetic engineering tools are regarded as machines. “…life is being remade in novel and surprising ways as iGEM students use increasingly fast and cheap genetic engineering tools.”

- From Immunity to Collaboration: Microbes, Waste, and Antitoxic Politics (Amy Zhang). Research details “urban waste activists in China who are practicing a quiet form of resistance to the policies of the authoritarian state by using the fermentation of eco-enzymes to heal sickened rivers, bodies, and soils.”

- The Nectar of Life: Fermentation, Soil Health, and Bionativism in Indian Natural Farming (Daniel Münster). Münster delves into agricultural politics in India. He concludes that “fermentation’s effects are unpredictable: there is always more than one story to tell.”

- Microbial Antagonism in the Trentino Alps: Negotiating Spacetimes and Ownership through the Production of Raw Milk Cheese in Alpine High Mountain Summer Pastures (Roberta Raffaetà). Raffaetà investigates cheesemaking in the Italian alps, contrasting three different approaches — farmers who don’t use contemporary cheesemaking methods and only use microbes found in their terroir, , industrialized cheese producers,; and high-mountain farmers who mix cheesemaking elements from different times, such as using a standardized starter with local cultures.

- Protecting Perishable Values: Timescapes of Moving Fermented Foods across Oceans and International Borders (Heather Paxson). Raw milk cheese, cured meats and assorted ferments get their flavor from microbes. Paxson documents how transportation and distribution can erode the microbial content of these products, especially international imports. She concludes supply chains (especially international) should be further explored to make transporting products with live microbes viable.

- Enduring Cycles: Documenting Dairying in Mongolia and the Alps (Björn Reichhardt, Zoljargal Enkh-Amgalan,Christina Warinner, and Matthäus Rest). This research details the Dairy Cultures Ethnographic Database, an open resource featuring photos and videos of dairy production, landscapes and livestock in the Alps. Interviews, oral histories and folk songs are also included.

- Preserving the Microbial Commons: Intersections of Ancient DNA, Cheese Making, and Bioprospecting (Matthäus Rest). Rest traces the history and spread of dairying in Mongolia, Europe and the Near East. She concludes by calling on scientists and local producers to protect the “microbial commons” from “patenting and commodification.”

- Taste-Shaping-Natures: Making Novel Miso with Charismatic Microbes and New Nordic Fermenters in Copenhagen (Joshua Evans and Jamie Lorimer). This research for this paper took place at Noma in Copenhagen, and studied how fermentation allows the restaurant to tread a fine line “between ecologically responsible localism and the nativism associated with the rise of Denmark’s anti-immigrant right. Noma’s chefs have hit upon kōji, Japan’s “national fungus,” which they turn loose on Danish ingredients.”

- Bamboo Shoot in Our Blood: Fermenting Flavors and Identities in Northeast India (Dolly Kikon). Kikon explores fermented bamboo, a delicacy in India, and how it’s part of the local the community.

- Fermentation in Post-antibiotic Worlds: Tuning In to Sourdough Workshops in Finland (Salla Sariola). Sariola describes fermentation “as a politically progressive form of performance art.” She documents activities in China, where fermentation is used to “challenge the modernist regimes of purification that have turned microbes into the enemy. To learn to live better with microbes is to learn to live better with other kinds of difference — those associated with ethnicity, race, national origins, sexual orientation, ability, and age.”

- Published in Science

Katz on Fermentation, Ancient & Modern

When Sandor Katz was asked to teach his first fermentation workshops in the early ‘90s, he figured it would have only niche appeal. Instead, people filled his workshops, begging for more information and calling on him to host similar events all over the U.S. “People [were] hungry for more information on fermentation,” he says.

“Humans didn’t invent fermentation. Fermentation is a natural phenomenon that existed before we did,” Katz says, speaking from in front of a wall of ferments and spices in his home kitchen in Tennessee. “Fermentation is an essential part of how people everywhere make effective use of whatever food resources are available to them. Food fermentation is not precious; fermentation is practical.”

Katz was a keynote speaker at the FERMENTATION 2021 conference. He shared his personal journey into the subject as well as his thoughts on fermentation as a natural phenomenon.

Fermentation as Trend

Katz says people are excited about fermentation for different reasons — some have memories of fermenting with their grandparents and want to try it at home, others are immigrants wanting to recreate dishes from their native countries, some are farmers hoping to preserve a surplus of produce, others are interested in the health benefits and some are foodies chasing the delicious flavor.

He hates equating fermentation with trends, preferring the term “fermentation revitalization” — the demographics of people currently making fermentation “trendy” again hasn’t really changed in the last 30 years.

“Fermentation has been so important to food traditions everywhere, and yet because of factory food production, one-stop shopping convenience foods, fewer and fewer people were practicing fermentation,” Katz said, recalling his workshops in the early days. “It was becoming more mysterious to people. Now there’s no denying that fermentation is trending. There’s a heightened awareness of fermentation, but people don’t realize the products of fermentation have been so integral to how everybody, everywhere eats. Without even thinking about fermentation, people have always been eating products of fermentation.”

The “War on Bacteria”

But there has long been fear around fermentation from some consumers. Katz says many people “project their anxiety about bacteria onto the idea of fermentation.”

“For people of my generation and older, we never heard anybody say anything positive about bacteria. The degree that bacteria were talked about at all, it was about how dangerous they are and how much they need to be avoided. I grew up in a period that could be described as the war on bacteria, this idea that bacteria are pathogenic, bacteria are dangerous to us, bacteria must be avoided and you know we have an arsenal of chemicals that we can use to kill bacteria as needed to keep us safe.”

The U.S Department of Agriculture has never had a case of foodborne illness from fermented food or beverages, Katz notes. “Statistically speaking, fermented vegetables are safer than raw vegetables.”

Facing people’s questions and fears motivated Katz to write his first book, The Art of Fermentation. This month, he released his 6th title, Fermentation Journeys: Recipes, Techniques, and Traditions from Around the World.

Fermenting the Future

Katz is an advocate for decentralizing food production, replacing a global supply chain with local, farm-fresh sources. Though this will raise the cost of food, it will put fermentation as a key means of preserving a surplus of seasonal crops, Katz notes.

Even as more and more chefs and producers apply different processes to different substrates and play with flavor, Katz says the fundamental processes remain the same. Nothing new has been invented in fermentation, which dates back 10,000 years.

“Fermentation of the future grows out of the techniques and traditions of the past,” he says. “Anything you can possibly eat can be fermented, so I’m never surprised when something is fermented.”

Katz shared his story of fermenting a goat on the rural Tennessee farm he lived on in the ‘90s. After the animal was butchered, he took the leftover pieces and fermented them for a few weeks in a mix of miso, yogurt and sauerkraut juice. When cooked, the meat released a strong aroma, a scent that became legendary on the farm. But, Katz says, “It was delicious. Like many things, it had a stronger aroma than flavor.”

Health Benefits Come with Warning Labels

When asked about the curative health benefits of fermented foods, Katz does not mince words. He wrote in Wild Fermentation that fermented foods were an important part of his healing when he was diagnosed with HIV in 1991. Since then, numerous media outlets have twisted his story, writing that Katz cured himself from HIV with fermented foods.

“I have become much more cautious about how I talk about this,” he says. “There’s a lot of highly speculative information out there…and I’ve never seen data that would suggest that.”

Katz says he’s careful to rely on reputable scientific studies for data on fermentation’s health benefits. He says he’s read articles claiming kombucha will prevent hair from going gray. Pointing to his full head of gray hair, Katz smiles and says “When I started teaching about fermentation, my hair didn’t look like this. Time marches on.”

“Food has profound implications for our health and well-being and for how we feel, but singular foods are very rarely the cure to specific diseases. …There are many benefits to fermentation, whether it is simply from pre-digestion of nutrients that makes nutrients more bioavailable and accessible to us or whether it’s from the probiotics or whether it’s from metabolic byproducts which can be extraordinarily beneficial to us.”

- Published in Food & Flavor

Analyzing Mexico’s Traditional Fermented Beverages

A research team has made the first comprehensive analysis of Mexico’s traditional ferments. Utilizing the country’s native cacti, agaves and maize, these diverse beverages are unique to their region. But they are poorly studied, and some are endangered as they fall out of style with younger generations.

“Many of Mexico’s finest microbiologists and ethnobotanists are giving ever-greater attention to this fascinating but once-forgotten foodscape, but even they are willing to admit that we’re just beginning to scratch below the surface of understanding all the biodiversity in these bottles of blessed ferment,” says Gary Paul Nabhan, research scientist at the Southwest Center of the University of Arizona (U of A).

Researchers in various disciplines (microbiology, ethnoecology and genetics) from five different schools (U of A and four universities in Mexico) took part in the study. The results, Traditional Fermented Beverages of Mexico: A Biocultural Unseen Foodscape, are published in the international journal Foods.

Sixteen traditional Mexican fermented beverages were identified: tepache, pulque, hobo, Mexican wines, colonche, nawait, pozol, sidra, tejuino, tesgüino, taberna, cocoyol, tuba, Mexican palm wine, balché and xtabentún. Those 16 drinks were made from 143 plant species and include 102 genre of microorganisms.

In each region, “a distinctive set of plant roots, leaves, fruits and stems were added as fermentation catalysts, flavorants, colorants and stabilizers,” reads the U of A press release. “A large number of bacterial strains and yeasts — in addition to common brewer’s yeasts and water kefir grains — enabled the nutritional transformation of these raw materials into a wide array of unique nutritionally rich, probiotic beverages.” The team mapped the regional variations and ecological niches of the fermented drinks.

Sustainable Future

The study notes this level of analysis is “indispensable” to promote fair trade and sustainable food production. Industrial mezcal, for example, has created a monoculture of blue agave, and farm labor often works in exploitative conditions.

“These products have been embedded as part of the daily lives of many people, including those currently marginalized rural or Indigenous groups,” the study reads. “The diversity of fermented products is an outstanding reservoir of genetic resources that has high potential to obtain secondary products such as extracts, enzymes, dyes, and others compound that can be involved in global markets and could help to solve problems such as hunger and poverty and may play a key role to reinforce cultural identity..”

Traditional Mexican fermented beverages also provide important nutrients for consumers as the globe battles a changing climate.“The naturally-occurring yeasts and kefir-like tibico grains found in association with prickly pear cacti, saguaro fruit, century plants and desert spoons (sotols) likely tolerate much higher ambient temperatures than those from the semi-arid highlands and wet tropical forests,” Nabhan explains.

Extinct Drinks

Some healthier artisanal drinks “have fallen out of fashion and face local or broad extinction,” the press release notes. In some areas of the country, these “forgotten ferments” are still used in the home, but not commercialized.

“Now that the days of Prohibition are over and there is a great need for arid-adapted crops with highly-efficient water use, some of these traditional agave and cactus varieties should be revived for the local production of healthful beverages,” Nabhan suggests. “In fact, traditional beverages such as tepache, tesguino and colonche have made a comeback in the Tucson, Arizona, region since it received recognition as a UNESCO City of Gastronomy. These traditional beverages are also being employed by mixologists in novel cocktails now being featured in nearly every state of Mexico.

- Published in Food & Flavor, Science

Chocolate Without the Cacao

Cacao is one of the most environmentally harmful and ethically dubious commodities produced on the planet. It plays a huge role in deforestation, uses an alarming amount of water and more than 2 million children work in cacao farms. Yet cacao hasn’t been reimagined the way other foods with similarly harmful footprints have.

“There’s a lot of ethical quandaries around the production of chocolate,” says Johnny Drain, PhD, co-founder of WNWN Food Labs. “Cacao is a huge contributor to climate change, and child labor and slave labor are hardwired into the supply chain.”

Drain’s nickname is the “Walter White of fermentation” because of his work helping pioneering restaurants and bars around the world incorporate fermentation into their food and drink. Now Drain can add “Willy Wonka of chocolate” to his resume. He is co-launching a cacao-free chocolate, next in the wave of alternative products designed to replicate flavor and texture without a harmful production cycle.

A Chocolate-Potato Connection?

WNWN (Waste Not, Want Not, pronounced “Win-Win”) happened by chance. About five years ago, Drain was boiling old, green potatoes, and leaned his head into the steam. He was surprised it smelled like chocolate.

“I had this light bulb moment where I thought ‘There must be some compounds within the skins that are also found in cacao and chocolate.’ I wondered — ‘Could I make chocolate from potatoes? What other weird and wonderful things could make chocolate?’” Drain says.

WNWN plans to release a small-run batch of their chocolate next month. Drain and co-founder Ahrum Pak, a former investment banker and fellow fermenter-turned-food-activist, are calling the product category choc.

WNWN’s choc ingredients are proprietary until its formal release but, as with traditional chocolate, they are plant-based and fermented. Drain describes them as familiar, whole ingredients that are common in an average person’s diet.

“It’s not a Frankenstein, lab-created product, mixing this potion with that potion. We take whole ingredients, we ferment them just as we would chocolate, then we end up with this delicious chocolatey paste that goes into a quite conventional chocolate-making procedure,” Drain adds.

WNWN also replaces cocoa butter — made from cacao pods — with plant-based oils. Cocoa butter is what gives traditional chocolate a silky, creamy texture as it melts in your mouth.

Fermented Flavors

At the heart of choc’s flavor, though, is fermentation.

“Cacao is fermented to make chocolate in the same way our product is fermented. We use similar, friendly microbes to create complexity,” he says. “We’re recreating that flavour profile of chocolate that we all know and love using the same fundamental techniques that are used to make chocolate.”

High-quality chocolate contains roughly 600 different flavor and aroma molecules. Cacao fermentation involves lactic acid and acetic acid bacteria, along with various yeasts, to create its flavor.

“If you didn’t have that cocktail of microbes, you would end up with something that only tastes vaguely like the chocolate we know and love,” he adds. “At the heart of this is fermentation. The product that we have, if we produced it without the fermentation processes, it wouldn’t taste anything like chocolate, just like if you eat a raw cocoa bean or even a roasted, unfermented cocoa bean, it doesn’t really taste like chocolate. You have to have that very complex cascade of chemical reactions, made possible by the fermentation, to get the final chocolate flavour.”

The Next Big Alt Movement?

Drain is quick to point out WNWN is not the only company trying to create what he and Pak have coined “alt-chocolate.” Three companies — QOA, Voyage Foods and Cali-Cultured — all officially launched in the past three months.

Some of these companies have been operating in stealth mode for a number of years but made official launches once word of competitors began to circulate. QOA and Voyage appear to be using approaches similar to that of WNWN. CaliCultured is using a syn-bio precision fermentation route to modify yeast cells to produce lab-grown cacao cells that are genetically identical to those found in the wild.

Drain says he’s encouraged by the other companies.

“It’s exciting that there’s multiple people working in this space,” he says. “Look at the plant milk space or alternative protein space — there’s definitely plenty of room in this marketplace too, and collectively we are all doing this because we care about the ethical and environmental damage being wrought by the current cacao supply chain.”

European and American consumers historically dominate chocolate sales, but chocolate sales all over the world are increasing.

Drain and Pak feel that a shake-up in the industry at the top is needed. Huge international producers are responsible for the vast majority of global chocolate. Mars, Nestle and Hershey promised over 20 years ago to stop using child laborers, but reports say the problem continues.Similarly, these companies pledged a decade ago to source more sustainable chocolate, but negative environmental problems from cacao continue to increase.

“The way in which we consume food has to change. It’s unrealistic that millions of tons of mass-produced cacao is somehow ethically- and sustainably-produced,” Pak says.

Drain adds; “So, really, we’re not anti-chocolate, we’re anti-big-chocolate produced in unethical, unsustainable ways.”

Recreating Food

Chocolate is merely the first challenge that WNWN wants to address. Coffee and vanilla are next, foods with similar human rights and sustainability concerns. The company is building a software system that can ideate fermentation pathways for creating sustainable, flavour-identical analogs to delicious – but unsustainable – products.

“When you really start looking at how most of the world’s food is produced and consumed, there are so so many cases where it’s produced in a really terrible and damaging way,” Drain says. But “the market wouldn’t have been ready for a product like this five years ago. People are becoming much more aware of where their food comes from. People are thinking about ‘How do I make my purchasing habits, my diet better for the planet in a way that I don’t have to sacrifice the flavors and taste that I love?’ There will be work to do. But people are more receptive now that fermentation is more of a household name than it was five years ago. I think the fact that more people want to remedy these challenges is brillant.”

Drain will be speaking FERMENTATION 2021 on “The Alt-Universe”

- Published in Business, Food & Flavor

How Important is Consumer Education?

This is the second in a series of articles that TFA will be releasing over the next few months, analyzing trends from our Member Survey.

Fermentation is cloaked in mystery for many consumers — it’s bubbly, slimy, stinky and not always Instagram ready.

So how can fermentation producers appeal to potential consumers? What’s the best way to share fermentation’s flavor and health attributes?

In The Fermentation Association’s membership survey on industry trends, a better-educated consumer was identified as a priority. When asked what would foster increased consumption of fermented foods and beverages, the top item for nearly 70% of producers was greater consumer understanding of fermentation and familiarity with the flavors associated with fermentation.

“More than wanting to sell a product, I want people to know the information,” says Sebastian Vargo of Vargo Brothers Ferments (who is speaking at FERMENTATION 2021). The Chicago-based brand sells ferments like pickles, sauces and kombucha. “I believe preventative health starts with fermentation. I’m explaining the difference between a pickle you see on the shelf versus a pickle you see in the refrigerator. But I’m also teaching people to power up their pantry, sauce up their life with condiments.”

Health vs. Flavor

Producers say they struggle sharing fermentation’s benefits with consumers. There are not enough peer-reviewed scientific studies on many fermented products to be the basis for health claims.

“We feel a responsibility as a fermented food company to entice customers into trying these hugely beneficial and delicious products,” says Savita Moynihan, who owns SavvyKraut in Brighton, UK, with her husband Stevo. But, “with sauerkraut, it is generally understood that raw and unpasteurised kraut is good for you but once you try to elaborate on live culture vs probiotics it gets complicated, more than it needs to be.”

Can a brand claim to include probiotics? Producers feel that guidance is not clear.

“There is confusion here that we feel needs to be ironed out in order to loosen the reins so fermenters can promote their products and their benefits with much more confidence,” she adds.

Moynihan says that, when SavvyKraut sells at farmers markets and local shops, they try to communicate two main things to consumers. First, the health benefits, like enhanced vitamin and nutrient contents, increased fiber and an aid to a diverse gut and digestive system. Second, the delicious flavor.

“The process of fermentation really enhances the flavours and creates an entirely new type of flavour which can elevate any meal,” Moynihan adds.

Lack of Tastings Hurting Efforts

One of the best ways to familiarize consumers with fermentation is for them to taste a product — flavor is a great marketing tool. But COVID-19 has hurt these efforts. Producers are unable to stage in-store demonstrations, offer samples at farmer’s markets or host in-person events. This has been especially hard for kombucha brewers, says Hannah Crum(who is also speaking at FERMENTATION 2021), president of Kombucha Brewers International (KBI).

“We still have such a big part of the population who don’t drink kombucha or don’t even know about [it]; we still have a lot of work in education,” Crum says.

Joshua Rood, CEO of Dr Hops Hard Kombucha, confirms, adding: “It continues to be very difficult to grow our brand and the whole category without live events.”

“The inability to do live tastings in 2020 had a significant diminishing impact on our sales during the pandemic,” he continues. “One of our main distinctions as a brand is superior taste. Consumers, however, do not believe claims about that unless they experience it for themselves. Even now we are significantly hampered by the lack of large beer festivals and street fairs. An artisanal craft brand like Dr Hops needs those live interactions!”

The Knowledge Gap

Despite the lack of in-store tastings, experts at New Hope Network (producers of the Natural Products Expos) say brands have a great opportunity — now, more than ever, during the COVID-19 pandemic — to connect with their consumers.

New Hope’s 2021 Changing Consumer Survey found U.S. consumers are not satisfied with their current health. Only 8% say they’re “extremely satisfied” with their health today, compared with 20% in 2017. Nearly 80% of consumers understand that diet greatly influences their health (79%). But achieving good health is both a goal and a struggle for consumers — and this is where brands can step in.

“There’s a gap to be bridged,” says Eric Pierce, vice president of business development for New Hope Network, during a session “Understanding Your Consumers” at the most recent Expo East. “I see it as our opportunity and our responsibility to help consumers translate healthy intentions into healthy behavior, either in how we’re educating them in our stores, the products that we’re innovating or the ways we’re communicating. Getting better at communicating can help them with solutions.”

A consistent, transparent, well-communicated message — from product label to social media page to website — is important. Pierce says consumers quickly see past “shallow marketing claims.”

“Leave a trail of breadcrumbs people can find,” Pierce advises. “You don’t have to communicate everything all at once, but allow people to follow a trail to the deeper story. When consumers want to find that trail, if it’s not there, they’ll quickly write you off as shallow with unbacked claims.”

Amanda Hartt, market research manager at New Hope, suggests putting a QR code on a product label that links to the science backing the benefits of your ingredients. Or partnering with a registered dietitian on social media to highlight how to use your product as part of a healthy diet.

[To learn more about this topic, register for FERMENTATION 2021 to hear one of the keynote panels “Educating Consumers About Fermentation.”]- Published in Business, Food & Flavor, Science

Q&A: Melinda Williamson, Morning Light Kombucha

Melinda Williamson has always been fascinated by plants — she grew up watching her mother make baby food with produce from the garden, later studied medicinal plants in college and dedicated her career as an ecologist to researching microbial communities in soil.

So, when Williamson became extremely sick with an autoimmune disease eleven years ago, it was not surprising that she turned to plants. She began making green smoothies daily and, after a student shared a bottle of it with her, drinking kombucha.

“I became really conscious about what I was putting in my body, really focusing on where my food was coming from,” says Williamson, founder of Morning Light Kombucha in Hoyt, Kansas. “I started researching my illness, and found that a lot of stuff stems from the gut. It brought me into this world of ferments.”

The health-scare-turned-health-revival changed the course of her life. Mother of a then-young child, Williamson moved back to Kansas to raise her daughter closer to family. She took a language program job on the Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation reservation in her hometown, then spent her hours off work fulfilling a dream of running her own business. She perfected a home-brewed kombucha and began selling it at local farmers markets, gas stations and yoga studios.

The pandemic easily could have shuttered a small brewery like Morning Light which, prior to 2020, Williamson ran on her own. But she designed a website, opened an online store, started curbside delivery and launched a canned line — and sales grew by 25%. By the end of 2021, Morning Light Kombucha will start shipping nationally and, by the end of next year, they plan to break ground on a 4,000-square-foot facility on the reservation.

“What I really want to do is get my product into more native communities, so they can find healing just like I found healing,” says Williamson, head of the only Native American kombucha brand. “That’s more important to me than seeing my product on the shelf of Wal-Mart or Target. I’m not in it to be rich. I still plan on living in my little house here on the reservation close to my family. I just want to do something that has meaning and an impact.”

Below is an edited Q&A between Williamson and The Fermentation Association.

TFA: Where do you get your ingredients? You forage some of the ingredients yourself on the reservation.

MW: We go out and harvest wild blackberries, wild raspberries, chokecherries and pawpaws mostly on the reservation. There’s edible plants everywhere, it’s surprising the places you can find them. We just went to Overland Park, which is the city near us, to forage for pawpaws.

Some of the ingredients like gooseberries, those we find in small quantities. If we go out and we only get four cups of berries, we may not make any kombucha with it. But sometimes I’ll make a little five gallon batch.

Most of our ingredients, we partner with local farms in Northeast Kansas. It comes down to the importance of knowing where our food comes from. My goal was to always work with local farmers and source ingredients locally, I knew I wanted that as part of my business foundational value.

As much as possible, we keep sustainability at the forefront of everything that we do, being really conscious about our footprint. It’s really nice because, being in Northeast Kansas, people aren’t thinking about stuff like that. They’re more and more thinking about where their food comes from, but it’s been really nice to have those conversations with the community and get people really thinking about supporting the local farming economy, supporting local business.

A big part of it really comes down to what we’re showing our kids. Before my daughter was born, I had her when I was 23, I was eating a lot of fast food. I was like “I’m free! I’ve got a job! I can buy and eat whatever I want!” I was eating so much junk food. And then I got pregnant and wanted to feed her properly. I grew my own garden and started making my own baby food, just like my mom modeled for me. Food is so important, it’s a constant conversation in my life and in my business.

TFA: Do you make seasonal flavors then?

MW: We launched our canned kombucha line in February. Prior to that, we were doing about 100 flavors a year, so now that we’ve launched our canned kombucha line, we’ve had to whittle that down because we have to have four flavors constantly. Our rotations have diminished a little, but we’re still putting out about 60 flavors a year.

Our berry flavors are our most popular — blackberry lemongrass and strawberry. Seasonally, our smaller batches that people love are mulberry, that is a top seller. People also love the ginger and chokecherry flavors.

TFA: How do you sell your small batches? Are you selling them retail or filling kegs on site?

MW: We sell direct-to-consumer, like at the farmers markets and events. We don’t have a brewery that’s open to the public. We do curbside pickup, that was something that was developed in response to the pandemic. We could no longer sell directly to the consumer, so we just started doing doorstep delivery, then the curbside pickup. Basically, people just have their empty bottles in their trunk and call us and we come out and grab their bottles, and swap them for new, filled bottles. It’s contactless, but we still got to see our customer and wave. We’ll probably continue to do that, we’re still in this pandemic, and the most important thing is to keep our community safe and our elders up here safe. We will continue taking all precautions to protect people around us until we hit a safe spot.

TFA: A portion of your sales goes back to the native communities. Tell me about that.

MW: We donate where we feel like the money would be used best, things that we’re passionate about and things where we see we can make a difference. For example, we just recently donated to one of the residential school survivor nonprofits. We’ve taken clothes to Standing Rock Sioux Tribe where they were protesting the Dakota Access Pipeline, we’ve donated to our Boys and Girls Club here on the reservation, we’ve donated to our youth soccer teams, we’ve donated to First Nations programs in Canada.

TFA: Morning Light Kombucha is a trademark American Indian Food product. What does that mean?

MW: So that trademark American Indian Food falls under the Inter-Tribal Agricultural Council, which is a subset under the USDA. The program really highlights American Indian food producers. You apply and then the program supports you in different ways. We’re able to network with other American Indian food producers, brainstorm together and talk about what we’re experiencing and try to make movements when it comes to distribution. The program is really big with international exporting, so all the American Indian food producers have the opportunity to attend large trade shows internationally, they’ll fly us there, ship our products and give us the opportunity to have a booth and get our product in front of people who are interested in American Indian food products. I’m not ready for something that big, I am so small, but I’ve gone to a domestic show through the program. I went to a food show in Chicago and got in front of a lot of people who are interested in my kombucha. We have really big plans in 2022 to expand our facilities, and hopefully expand domestically.

TFA: What are Morning Light Kombucha’s plans for 2022?

MW: I just bought 10 acres here on our reservation. My plan is to break ground and build a production facility. It will be three times the size of what we’re in now, which will be really, really nice. There’s a pond on the side, we’ve got a creek, timber, a lot of foraging areas. The plan is to build an off-the-grid brewery, too, so it will help us provide more jobs in our community and it will allow us to do some of the things that we haven’t been able to do.

I mentioned sustainability is a big part of what we do. We compost 100% of our brewery waste, but I have to truck it to my house to my compost pile because, where we’re at now, we just can’t compost large quantities at our site. The waste water from our water filtration system, it’s totally usable water, but we don’t have any place to store it currently. Our waste water is not like gray water, it’s clean water that’s just wasted during the filtration process, it’s usable. For every one gallon that’s filtered, there’s three gallons that’s wasted. It’s so insane, it killed me when I found that out. Once we are in our new facility we can begin to recycle it on property. We have this dry pond. Our plan is to see if we can get it lined, divert the waste water in there and start filling the pond.

TFA: Scaling will be big for you in 2022.

MW: I know, I just hired three employees recently because it’s just been me for the past few years. I work part-time for our language department, and my kombucha business has been my side hustle. In the past year, I’ve realized the potential. People really like my brand and they’re noticing it and requesting it. So I thought “Maybe I could grow this brand into something bigger.”

TFA: I am beyond impressed — you have been building a kombucha brand by yourself?!

MW: Family is always there for me. My boyfriend is at the market, my nephews help with anything I need, it’s a family affair even though I never really had anybody on my payroll until recently. Now I’m getting to a point where I need help all the time. I hired my sister as my brewery manager, she keeps a tight ship. It’s allowed for me to really work on expansion while she’s running operations at the brewery.

TFA: Yours is still the only Native American-owned kombucha brand.

MW: With my business, I like to think that I’m also giving a voice to native issues. I would never want to be an authority on native issues, but there’s a lot of things going on in Indian country that people don’t see in the mainstream media and mainstream social media. If I can build a brand that can also bring awareness to these things, that’s really important to me.

TFA: You have a background in academia. What got you interested in ecology before switching to kombucha?

MW: I’ve always loved science, I’ve always loved the outdoors, I’ve always been super eco-friendly, I’ve always been conscious about our impact on the earth. I love animals, I love nature. I was taking some of my general ed classes at Haskell (Indian Nations University) and took an ethnobiology class. I just fell in love. I ended up transferring to Kansas State and got my degree in environmental biology (then a masters degree in rangeland ecology and management from Oklahoma State University.) I went with my boss from K State to Oklahoma State and ran the grassland ecology lab for years.

TFA: Where do you see the future of fermentation?

MW: There’s an explosion. I see it continuing to grow and expand and people are coming out with really innovative ways to bring fermentation to the table. Like Wild Alive Ferments out of Lawrence, Kansas. We’re a part of a local CSA with them. The owners just came out with an apple kraut flavor, an autumn harvest with spices that is so amazing.

In the U.S. especially, we have a lot of people who are sick with illnesses or cancers and autoimmune issues and I think we’re starting to see more people look at what they’re putting in their bodies. They’re realizing the importance of gut health, the importance of ferments, and that it affects so much more than just your gut. It’s a movement — and I’m really excited about it.

- Published in Business, Food & Flavor, Health