Kefir Brands Respond

The kefir brands recently tested for their probiotic claims are challenging the results.

In May, a study found 66% of commercial kefir products overstated probiotic counts and “contained species not included on the label.” The Journal of Dairy Science Communications published the peer-reviewed work by researchers at the University of Illinois and Ohio State University.

“Based on the results…there should be more regulatory oversight on label accuracy for commercial kefir products to reduce the number of claims that can be misleading to consumers,” reads the study. “Classification as a ‘cultured milk product’ by the FDA requires disclosure of added microorganisms, yet regulation of ingredient quality and viability need to be better scrutinized. All 5 kefir products guaranteed specific bacterial species used in fermentation, yet no product matched its labeling completely.”

Researchers tested two bottles of each of five major kefir brands: Maple Hill Plain Kefir, Siggi’s Plain Filmjölk, Redwood Hill Farm Plain Goat Milk Kefir, CoYo Kefir and Lifeway Original Kefir. Bottles were measured for microbial count and taxonomy to validate label claims.

The Fermentation Association reached out to the five brands involved and asked for their responses to the results. Redwood Hill and Lifeway both submitted detailed statements. Maple Hill, Siggi’s and CoYo did not return multiple requests for comment.

Probiotic Count

Probiotics in fermented products are listed in colony-forming units (CFUs), and the study found kefir from both Lifeway and Redwood Hill contained fewer CFUs than what was claimed on the label. But these brands — who send their products to third-party labs for testing — said the results are not accurate.

Lifeway refutes the assertion that their Original Kefir did not meet the claimed probiotic count. Lifeway references U.S. Food and Drug Administration food labeling laws, which dictate that a product “must provide all nutrient and food component quantities in relation to a serving size.” Lifeway’s label on their 32-ounce bottle says that the serving size of kefir is 1 cup, making the claim of 25-30 billion CFUs per serving size accurate.

The study results, Lifeway notes in their statement, were “premised upon an erroneous assumption that Lifeway claims it has 25-30 billion CFUs per gram” rather than per serving size.

“The authors’ flawed assumption is perhaps a result of their lack of familiarity with FDA labeling requirements or a result of merely overlooking the details in order to support their intended conclusions going into the testing,” reads a statement from Lifeway.

In fact, Lifeway points out, the study’s “erroneous conclusion premised upon the flawed assumption…actually proves the accuracy of Lifeway’s claim of 25-30 billion CFUs per (8 ounce) serving.”

Redwood Hill Farm, too, refutes the study’s conclusion. Their Goat Milk Kefir currently includes the phrase “millions of probiotics per sip” on its label. The label referenced in the study was an old version that claimed “hundreds of billions” of probiotics, which was discontinued last year. According to Redwood Hill Farm, that old label was based on third-party testing that confirmed hundreds of billions of CFUs per 8-ounce serving. But careful review of the kefir’s probiotic counts in 2019-2020 found some CFUs in the hundreds of billions and others in the tens of billions. Redwood Hill changed their label to millions rather than billions “to be absolutely sure that we could meet our target claim on a consistent basis.”

Variation in CFU counts is common in traditional plating testing techniques. Redwood Hill referenced a study published in Nutritional Outlook that found that plating results can vary 30-50%.

“Given the challenges around probiotic CFU enumeration, we were not too surprised to see a discrepancy between the number of CFUs in our Goat Milk Kefir found in the study and our past analyses,” reads the statement from Redwood Hill Farm. “Like all living organisms, probiotics are challenging to control and measure. A particular microorganism’s ability to reproduce is impacted by a variety of factors, including temperature, oxygen level, variations in the nutrient composition of the milk, and pH level. Our kefir has a sixty-day shelf life and during that time the different types of bacteria in the product will peak and die-off in relation to the conditions those particular bacteria like. For example, fermented dairy products naturally become more acidic (lower pH) as they age and while some bacteria thrive in acidic environments, others’ reproduction is stunted. This makes the exact CFU count rather volatile not only from bottle to bottle, but also throughout the timespan between when that bottle leaves our facility and when it expires.”

Redwood Hill Farm’s most recent testing measured 400 million CFUs per gram or 96 billion per serving (1 cup). These figures compare with what the study found — 193 million CFUs per gram or 46 billion per serving.

“Although the University of Illinois study found only half the probiotic cells that our study did, this is actually not that wide of a variation in bacteria reproduction based on all of the conditional factors outlined above,” their statement reads.

Species Count

The study’s test results found all kefir brands contained species not on the label. Lifeway notes their culture claims are based on the time of manufacture, not on expiration date. “Moreover, the authors validate that all of the claimed culture species except for the bifidos, Leuconostoc and L. reuteri, (which could be at a low concentration due to time of shelf-life), were identified in their testing,” reads Lifeway’s statement.

Redwood Hill Farm says that, based on the study results (that “2 Lactobacillus delbrueckii subspecies or 3 Lc. lactis subspecies could not be identified” in their kefir), they are pursuing further analysis. They’ve contacted their culture supplier for further insight, and are sending new samples to a third-party lab.

“These cultures are at the heart of the product and are what transforms the goat milk into a yogurt drink with its characteristic thick and creamy texture and tart flavor,” reads the Redwood Hill Farm statement. “It’s difficult to understand how these core active agents in the kefir could not be present in the product at any stage in its lifecycle.”

DNA vs. Plating Methodology

The study utilized both DNA sequencing and traditional plating methodologies, even though plating testing alone is considered the industry standard for kefir. Plating testing for kefir is done in a microbiology laboratory where it’s incubated to determine bacteria colony growth.

The study itself notes: “Limitation of DNA-based sequencing methods could explain why taxa stated on labels were not detected and why unclaimed viable species were identified.”

Lifeway points out: “This concession as to testing limitations is critical to note as it is but one explanation of many as to why various species may have not been detected. First and foremost, the authors fail to validate the DNA extraction method to establish that it delivers all the available DNA in the type of dairy product analyzed; for example, they do not appear to have broken down the calcium bonds. Further, they appear to not have undertaken the required extra enzymatic treatments. Moreover, for their microanalysis, they are using MRS [a method for cultivation of lactobacilli] but only incubating for 48 hours. As most kefir products would contain a significant amount of Lactococci, there is a high chance of not detecting this species unless you go to 72 hours of incubation. Another unknown important factor in the testing is the time period within the cycle of the shelf-life of the product that was tested. This is critical as the longer the product sits on a shelf, the fewer number of live and active bacteria will be present.”

Meanwhile, Redwood Hill Farm says “our team will continue to educate ourselves on the application of DNA sequencing technology to fermented food product probiotic count analysis and what opportunities and limitations this methodology may offer versus traditional plating techniques.”

- Published in Science

Advances in Yeast

We’re in the midst of a yeast revolution, as genome sequencing creates opportunity for cutting-edge advances in fermented foods and drinks. Yeast will be at the forefront of innovation in fermentation, for new flavors, better quality and more sustainability.

“Understanding and respecting tradition is a key part of this. These practices have been tested for hundreds and thousands of years and they cannot be dismissed. There’s a lot the science can learn from tradition,” says Richard Preiss of Escarpment Laboratories. Priess was joined by Ben Wolfe, PhD, associate professor at Tufts University (and TFA Advisory Board member), during a TFA webinar, Advances in Yeast.

Preiss continues: “There’s still a place for innovation, despite such a long history of tradition with fermentation. A lot of the key advances in science are literally a result of people trying to make fermentation better.”

Wolfe, who uses fermented foods and other microbial communities to study microbiomes in his lab at Tufts, said “there’s this tradition versus technology conflict that can emerge.”

“I tell my students when I teach microbiology that much of the history of microbiology is food microbiology, it is actually food microbes, and they really drove the innovation of the field so it really all comes back to food and fermentation,” Wolfe says.

The technology relating to the yeasts used in fermentation has expanded enormously over the last decade, due heavily to advances in genome sequencing. Studying genetics allows labs like the ones Priess and Wolfe run to find the genetic blueprint of an organism and apply it to yeast. Drilling down further, they can tie genotype to phenotype to determine characteristics of a yeast strain. This rapidly expanding technology will disrupt and advance fermentation.

Priess predicted three areas of development for yeast fermentation in the coming years:

- Novelty Strains

Consumers have accelerated their acceptance of e-commerce during the Covid-19 pandemic and they’ll do the same for biotechnology, Priess says.

“Our industry does thrive on novelty,” he adds, noting there are beer brands already creating drinks with GMO yeast. “Craft beer is going to be the first food space where the use of GMOs is widespread — we’re seeing that play out a lot faster than I ever thought it would be with some of these products already on the market. Novelty does have value.”

Wolfe noted many consumers shudder at the idea of a GMO food or beverage, but microbes in beer are dead. Consumers are not drinking a living GMO in beer.

Yeasts also already pick up new genetic material naturally, through a process called gene transfer.

“It’s part of the evolutionary process that all microbes go through,” Wolfe says. “From my own lab and from other labs, cheese and sauerkraut and all these other fermented foods are showing so much genetic exchange that’s already happening.”

- Climate Change

The food industry must address growing concerns about climate change. Priess predicts breeding plants — like barley, hops and grapes — that are more drought-tolerant, or even using yeast technologies to increase yields or the rate of fermentation.

“Craft beer is massively wasteful,” Priess says. It takes between three to seven barrels of water to make one barrel of beer. “It is something we’re going to have to reckon with the next 10 years.”

Yogurt and cheese, too, produce large amounts of waste products.

- Ease of Genomics

The cost and time of genome sequencing has reduced significantly. It used to cost thousands of dollars and take many weeks to document a yeast genome. Now, it can be done for $200 in only a few days.

“The tools to deal with the data and get some meaning from it have never been more accessible. It’s incredibly powerful,” Priess says. “We’re developing solutions for products without millions of dollars.”

Priess does not agree with companies patenting yeasts, “it’s murky territory.” He believes fermentation and science should be about collaboration, not ownership and protection.

“Working with brewers and other fermentation enthusiasts, it’s this incredibly open and collaborative space compared to a lot of the industries,” he says. “I think that’s like our secret weapon or our secret value is that fermentation is so open in terms of access to knowledge as well as in terms of people being willing to experiment and try new things. That’s how it’s able to develop so quickly.”

- Published in Food & Flavor, Science

State of the Natural & Organic Industry

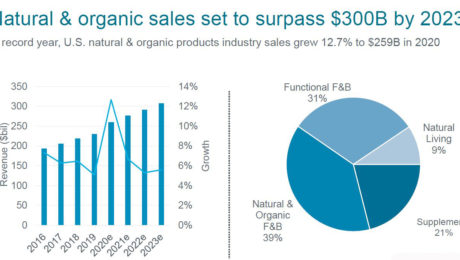

The Covid-19 pandemic powered strong food and beverage sales last year. But natural and organic brands grew even faster than conventional ones, with sales growing 12.7% to $259 billion.

“Natural products throughout the last year have really been outpacing all product growth. Natural and clean products are now about $1 out of every $10 spent, which is really significant,” says Kathryn Peters, executive vice president of SPINS, a retail data provider. Peters presented sales trends at the virtual Natural Products Expo West.

Data from SPINS and Nutrition Business Journal documents that there was a “dramatic shift” in consumer behavior during the pandemic, as more people cooked at home and bought healthier foods.

“2020 was a record year for the U.S. natural and organic product industry,” says Carlotta Mast, senior vice president and market leader for New Hope Network, producers of the Natural Products Expos. “The industry has so much to celebrate, despite the very challenging time we’ve been through the past 14 months.”

Natural and organic sales are expected to pass the $300 billion mark by 2023.

Food as Medicine

Functional food and beverage sales grew 9.4% to $78 billion in 2020, a surprisingly high figure since grab-n-go offerings — the category in which many functional products are tracked — were reduced significantly during the pandemic.

“And yet that strong growth, nearly 10% experienced in that category, demonstrates that people continue to embrace the food as medicine trend,” Mast says.

Products that claim to offer immune-boosting, functional ingredients are selling well. Consumers are “shifting from reactive to preventative and from cold and flu season to year-round protection.” Ingredients and supplements like elderberry, vitamins C and D, antioxidants, collagen and cider vinegar are increasing in sales.

Sales of animal welfare-positioned products grew 17% in 2020, and sales of grass-fed and free-range products increased more than 13%. Other key wellness attributes that appeared to drive significant dollar growth included paleo (up 32%), plant-based (21%) and grain-free (18%).

“Consumers are expecting more from the products they buy,” Peters said. “Whether it’s because of a limited budget or health and wellness considerations to build a stronger body, people are seeking nutritional benefits.”

Mission-Driven

Consumers are seeking to buy from brands with a purpose. These are products that, for example, want to save the environment, create a sustainable food system, champion a social justice cause or support a minority group.

Nick McCoy, co-founder and managing director at Whipstitch Capital, a food-focused investment bank, calls these brands “better for people and the planet” and says they are “doing good while making money at the same time.” The amount of ESG (Environmental Social Governance) investment funds has increased tenfold over the past two years.

Brands that are mission- and community-minded are experiencing the strongest sales growth.

“This demonstrates that our industry is home to brands that do a lot more than just sell a product — they’re a force for better, better health and better outcomes for humans, animals and the environment,” Mast says. “Our industry shoppers expect more than a transaction from the brands they do business with.”

In a SPINS survey, consumers said they want to support brands that are LGBTQ owned (19%), BIPOC owned (28%) and/or woman owned (18%).

Vegetarian and vegan products are also increasing in sales. Plant-based and meat alternatives grew 21% last year, at a rate of two-times their mainstream counterparts.

“In many cases, plant-based is bringing more nutrient density than the original animal-based analog,” Peters says . “Plant-based support is growing beyond just health benefits to earth-based benefits like lower greenhouse gas emissions, water conservation and biodiversity.”

E-Commerce

Not surprisingly, e-commerce sales fast-tracked during the pandemic, accounting for 58% of natural and organic sales last year. E-commerce also became the main channel where new brands were launched. Though sales in brick-and-mortar stores are not predicted to return to pre-pandemic levels, physical retail locations are still expected to account for 30% of all natural and organic products sales in 2023.

Speakers at the event advised brands to take an omnichannel approach, tackling marketing through brick-and-mortar stores as well as e-commerce channels. Sashee Chandran, founder and CEO of Tea Drops (a producer of organic tea pressed and preserved in different shapes), spoke at the conference about her experience following this marketing approach.

“Even though things are opening up, consumers still want that flexibility to be able to shop online but also in store,” she says.

- Published in Business

Artisanal Agave Spirits

Agave spirits are quickly becoming sought-after alcoholic beverages. Hearty desert plants, agaves spend years or even decades developing indigestible carbohydrates that can be hydrolyzed for fermentation, resulting in spirits like mezcal.

“We’re at a golden age of agave spirits right now,” says Lou Bank, cohost of the Agave Road Trip podcast. Bank and cohost Chava Periban shared the centuries-old fermentation processes used to create mezcal in the TFA webinar Artisanal Agave Spirits.

Adds Periban: “The beautiful thing about mezcal is we want diversity and you can use any agave under the sun to be able to make mezcal, which makes this category probably the most intensively diverse category in the spirits world.”

Tequila vs. Mezcal

Tequila and mezcal are both spirits distilled from fermented agave. But tequila can be made only from the blue Weber variety of agave and is made by steaming the agave’s heart (pina) in above-ground ovens. Mezcal can be from any of 30 types of agave and is made by cooking the agave in underground pits lined with lava rocks.

As the market for tequila grew, the term “tequila” was declared intellectual property of the Mexican government in 1974. Extensive regulations were established that, among other things, required tequila — formerly considered a regional type of mezcal — to come from only a specified area of Mexico.

Regulations for mezcal weren’t established until 1994, when it received its own Denomination of Origin. Similar to how champagne can only be made in a specific part of France, mezcal can only be made in nine of Mexico’s 32 states.

Periban and Bank point out a major issue with this certification process for mezcal. It ostracizes rural mezcaleros who may not have the money for certification or may not reside within the geographical boundaries.

“A lot of the communities and the traditions that nourish this nostalgia and this beauty of mezcal, they cannot use this word anymore to name their own spirits, the same spirits that they have been producing for centuries in their communities,” Periban says.

Adds Bank: “We love the flavors, but we are very much about preserving the process and in preserving the process, the number one ingredient in the process are the men and women who make the spirits.”

Bank runs a non-profit, SACRED (Saving Agave for Culture, Recreation, Education and Development), that helps improve lives in the rural Mexican communities where heirloom agave spirits are made.

Wild Fermentation of Agave Spirits

Tequila is made similarly to most alcohol — the producer pitches in a yeast to eat the sugar, picking a specific yeast for the desired flavor.

On the other hand, agave spirits such as mezcal and pulque are made in open air fermentation vats. Wild yeasts off nearby fruit trees change the flavor.

Bank estimates only 1 out of every 100 different commercial tequilas is made using pre-industrial, heritage processes. Mezcal, meanwhile, is just the opposite, with 1 in 100 bottles made using commercialized techniques.

“As the world gets more interested (in mezcal), you’re going to see more industrialization and you’re going to see less and less of this beautiful handmade stuff.”

Mezcal’s flavor palate varies by region, the agave type and the processing. Most mezcal is made and sold locally, to neighbors for weddings and religious festivities.

“If you’re making mezcal, you’re not just selling the product. You’re selling the drink that’s going to be part of their most important days of their lives,” Periban says.

Artisanal drinks with natural ingredients are on the rise, especially in America. Mark McTavish, president of 101 Cider House and co-founder & CEO of Pulp Culture (and TFA Advisory Board member), doesn’t see this trend slowing.

Mezcal, he says, will aid growth in the category, as it’s an alcoholic beverage that, instead of chugging, you sip to taste the complexity of the flavors.

“I really love fermentation and what it gives to a beverage, and I think it’s way more than just alcohol,” McTavish says. “There’s just such a richness there to the connection to a sense of place and a people behind it…that’s why fermentation is so beautiful.”

- Published in Food & Flavor

Defining Postbiotics

As postbiotics continue to trend among consumers, the International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) released a consensus definition on the category, published in Nature Reviews: Gastroenterology & Hepatology.

The panel of international experts that created the definition made it clear that postbiotics and probiotics are fundamentally different. Probiotics are live microorganisms; postbiotics are non-living microorganisms. The published definition states that postbiotics are a: “preparation of inanimate microorganisms and/or their components that confers a health benefit on the host.”

Inactive Microorganisms

A postbiotic could be whole microbial cells or components of cells, “as long as they have somehow been deliberately inactivated,” according to the news release by ISAPP. And a postbiotic does not need to be derived from a probiotic.

“With this definition of postbiotics, we wanted to acknowledge that different live microorganisms respond to different methods of inactivation,” says Seppo Salminen, professor at the University of Turku and the lead author of the definition. “Furthermore, we used the word ‘inanimate’ in favor of words such as ‘killed’ or ‘inert’ because the latter could suggest the products had no biological activity.”

The definition has been in the works for almost two years by authors from various disciplines in the probiotics and postbiotics fields. These include: gastroenterology, pediatrics, metabolomics, functional genomics, cellular physiology and immunology.

“This was a challenging definition to settle,” says Mary Ellen Sanders, ISAPP’s Executive Science Officer. “There are some who think that any purified component from microbial growth should be considered to be a postbiotic, but the panel clearly felt that purified, microbe-derived substances, for example, butyrate or any antibiotic, should just be called by their chemical names. We are confident we captured the essential elements of the postbiotic concept, allowing for many innovative products in this category in the years ahead.”

Growing Scientific Interest

Sanders continues: “The definition will be a touchstone for scientists, both in academia and industry, as they work to develop products that benefit host health in new ways. We hope this clarified definition will be embraced by all stakeholders, so that when the term ‘postbiotics’ is used on a product, consumers will know what to expect.”

Postbiotics have been on the market in Japan for years, and fermented infant formulas with added postbiotics are sold commercially in South America, the Middle East and in some European countries. ISAPP, in a release, notes: “Given the scientific groundswell, postbiotic applications are likely to expand quickly.”

The definition is the latest in a series of international consensus definitions by ISAPP. These include: probiotics, prebiotics, synbiotics and fermented foods.

- Probiotics: Live microorganisms that, when administered in adequate amounts, confer a health benefit on the host.

- Prebiotics: A substrate that is selectively utilized by host microorganisms conferring a health benefit.

- Synbiotics: A mixture comprising live microorganisms and substrate(s) selectively utilized by host microorganisms that confers a health benefit on the host.

- Fermented foods: Foods made through desired microbial growth and enzymatic conversions of food components.

- Published in Science

The Safety of Fermented Food

Thanks to lactic acid — which kills harmful bacteria during fermentation — fermented foods are arguably among the safest foods that humans eat. But if critical errors are made, there is the risk of food safety hazards.

“When we talk about fruit and vegetable ferments, there is a very long history of microbial safety with traditionally fermented fruits and vegetables,” says Erin DiCaprio, extension specialist at University of California, Davis, Department of Food Science and Technology. “While outbreaks associated with fermented fruits and vegetables are rare, vegetable and fruit fermentation is not without risk.”

DiCaprio, a food safety expert, detailed proper food safety protocols during a webinar for EATLAC, a UC Davis project putting scientific knowledge and research behind fermentation. DiCaprio shared two documented instances of fermented foods causing a foodborne illness, both from small-scale batches of kimchi. But she emphasized that, when all food safety concerns are mitigated, fermented foods do not pose a risk.

“From the food microbiology standpoint, bacteria really are the most important group of microorganisms because bacteria, certain types of bacteria, are a food safety concern,” she adds. “There are many different types of bacteria that contribute to food spoilage and, of course, there are specific types of bacteria that are used beneficially for fermentation.”

What happens during fermentation that makes food safe? Lactic acid bacteria are created, which convert sugars into lactic acid, acetic acid and CO2. Those antimicrobial compounds help fight off pathogens, competing with other microbes for nutrition sources.

Biological hazards — bacteria, viruses and parasites that can cause foodborne illnesses — are the biggest concerns. Botulism, E. coli and salmonella are the main hazards for fermented foods. Botulism can form in oxygen-free conditions if a fermentation is not successful and acid levels are too low. E. coli and salmonella form when sanitation practices are not followed.

“Commercially, when someone is developing a valid fermentation process, they are typically going to be looking to see that sufficient acid is produced during fermentation, to inactivate some of these acid tolerant (bacteria),” DiCaprio says. “Our traditional vegetable fermentations — things like fermented cucumber, sauerkraut, kimchi — they’ve all been shown to produce sufficient acid to inactivate the sugar toxin producing e-coli, so from a safety standpoint, sufficient acid production is the critical control point for ensuring the safety of a fermented fruit or vegetable. “

There are seven critical factors to keep a ferment safe:

- High-quality, raw ingredients. “If there are a high number of spoilage microorganisms to start with, it will be really difficult for the lactic acid bacteria to dominate the fermentation,” DiCaprio says.

- Research-based recipe. Following a tested recipe ensures the proper balance of ingredients to keep the food safe.

- Proper sanitation. Cleaning of all utensils and surfaces ensures no pathogens will contaminate the food. This mitigates cross-contamination risk, too.

- Preparation of ingredients. Food particles should be uniform in size, either cut in small slices or shredded. Smaller pieces release more water and nutrients, promoting the growth of lactic acid bacteria.

- Salt concentration. Lactic acid bacteria thrive in a salt brine. The key amount: anywhere from 1-15% salt brine by weight of the ferment.

- Appropriate temperature. A temperature between 65-75 degrees fahrenheit is ideal to keep spoilage microorganisms at bay.

- Adequate time. “It takes a while for significant acid to be produced, so be patient and follow the directions in the recipe,” DiCaprio advises. Most fruit and vegetable ferments take 3-6 weeks to be completed.

Q&A: Sophie Burov, Secret Lands Farm

When Sophie and Alexander Burov moved to Toronto, Canada, from Moscow, Russia, in 2007, farming wasn’t on their radar. Both entrepreneurs — she in fashion, he in mining — they were accustomed to life in one of the biggest cities in the world, not to rural farming. And their knowledge of fermented dairy was limited to taste — Alexander loved the tangy kefir he’d been drinking since childhood; Sophie devoured cheese and yogurt.

Sophie was a sheep’s milk aficionado, having tried it years earlier, She had fallen in love with its flavor, but soon learned how hard it was to find fresh sheep’s milk, especially in her native Russia. So when she met a producer at a farmer’s market in Canada, Sophie felt inspired to make her own sheep’s milk products.

“At that moment, I couldn’t even imagine running a farm,” Sophie says. She volunteered at a local dairy and sheep farm, quickly learning that: “Business is business and farming is business too, but it’s love as well. Farming is a lot of love.”

Today, Sophie, Alexander and their son Roman run the 150-acre Secret Lands Farms, south of Owen Sound in Ontario, Canada. Utilizing old-world European farming traditions, they produce a range of artisanal sheep’s milk dairy products at their on-site creamery: kefir, two varieties of yogurt, and 25 cheeses. Their kefir — made from centuries-old Tibetian grains — is also the base for their cheeses. Secret Lands is the only producer in Canada (and one of few in North America) using kefir grains as a culture for cheese.

“Seeing is believing — but tasting is falling in love,” Sophie says. “When you taste our product, you can feel the love.”

Sophie recently spoke with TFA; below are highlights from the interview.

The Fermentation Association: You purchased the farm seven years ago. Farming is hard work! Tell me what made you decide to purchase a farm?

Sophie Burov: Yes, we purchased it in 2013. The idea came about eight years ago. You know sometimes when you reach a point when you need to reconsider the purpose of your life and what you’re doing, why you’re doing it, what’s the purpose of your existing?

The agricultural sector is huge in Canada but not dairy sheep farming , so I started thinking about it as a hobby farm and we’d still live in the city, but it turned in a different direction because if you want just a hobby, it will only be your hobby. If you want something serious, your life and dedication is different when it’s your life. I believe it’s from guidance from God, I was praying a lot.

Looking back, this is the hardest job me and my husband have ever done. But it’s rewarding mentally. I believe in the spirit of the land and the animals and what you’re doing through the product you give to people, you become a bridge connection between the land and the people. Through the product, you can tell much more than through words.

If you want to go farming for money and there’s no love between you and the animals, forget it. There has to be love between you and the animals. Everyday they are teaching us how to be better human beings because sheep are very social. They are also very appreciative animals. They give back their love. If they’re struggling, you’re struggling with them.

We were very, very lucky, because we found the first sheep dairy farmers and breeders in North America — Axel Meister and his wife, Chris Buschbeck [owner of WoolDrift Farm in Markdale, Grey County, Ontario]. They brought this flock from Germany in the middle of the ‘80s and they started developing this flock in the middle of North America. When we decided to do this farm, we met Axel and started going to his farm and volunteering and he was guiding us, telling us what books to read and what to pay attention to with the sheep. His wife Chris is a vet for sheep and she helps us with our sheep.

TFA: How long did it take you to become experts at sheep farming?

SB: We are still learning. The first three years were extremely, extremely difficult. It was a hard time because, working as a volunteer at these different farms, it was very different compared to doing it yourself because all the ups, they’re yours, and all the downs, they’re yours.

TFA: Where do you sell your products?

SB: We sell at the farmers market on Saturday and home delivery twice a week. I believe home delivery is another bridge between the customers and us. If they have questions, we’re always here to answer. It’s not the easiest way to do it, but I believe that for small farmers and small producers, it’s the best way to connect with your customers and make money. We tried to work with retail stores, but retail chains, they are squeezing you. There’s no money for small farms. You can increase your flock, your production, to make more money, but we do not wish to become huge. For now it’s an ideal model for us to sell through online sales to all of the Canadanian provinces

TFA: What is a typical day like at the farm?

SB: Everyday is different. From the beginning, we were working like slaves. It was very unhealthy, all of us were sleeping just an hour, working at the farm then driving to the farmers market. Sometimes our working time was 22 hours a day, it was killing us. But now it’s easier because we have people who can help us in production and my husband Alex has people helping him on the farm, so it’s a little easier. [Secret Lands has anywhere from 8-10 employees, depending on the season].

The most difficult period of the year is lambing season. My husband and son are not sleeping at all. They have naps, but then they’re back to the barn. We do lambing once a year for a few months in spring. We do not do artificial insemination, we do it the way nature intended. The sheep are pasture-raised, grass-fed and no hormones.

TFA: You are Russian natives, where kefir originates from. Did you have kefir before starting the farm?

SB: Yes, kefir started in Russia, it began end of the 19th Century. It came from the Caucasus Mountains. But to be honest, when I started thinking about farming and a sheep dairy farm, I didnt even think about kefir, I was thinking about just yogurt because at that moment I was a yogurt and cheese person. I have hated kefir since I was a kid. My husband has been loving it since he was born.

But when we met our sheep breeder, at that moment he gave me a glass of kefir at his farm. He was just producing kefir for himself, I tried it and thought this was interesting. He gave me a handful of kefir grains, and I made kefir and brought it to our church community for people to try and share with people our idea of what we would be doing on the farm. One lady started asking me so many questions about kefir. And I realized my knowledge about kefir is null. I went back home and started my research and I was just shocked. It was so amazing, it was my ah-ha moment. Kefir is incomparable with yogurt in nutrition. Then my amazement was doubled, tripled, because sheep’s milk kefir, the product is different, the amount of calcium is much higher than cow’s or goat’s milk. In the kefir variation, our body will assimilate twice the calcium and protein.

The real kefir — made from kefir grains — it’s very limited on the market because it’s difficult to make. Seven years ago I had a handful of kefir grains, but now I can produce nine pails of 15 liters each of kefir at the same time. It’s not a huge amount actually if we compare it to someone who does it commercially. It’s impossible to make money with that amount of product. When people ask why our product is high priced, I tell them because it’s the real stuff.

TFA: Tell me some of the benefits of sheep’s milk kefir.

SB: It’s a natural probiotic, it’s the most natural probiotic in the whole world. Some scientists are saying it has 50 different variations of probiotics.

If you are taking pills or taking kefir from commercial cultures, you are not digesting the good bacteria. But if you take the real kefir, it’s becoming you and it works. People ask “Why am I supposed to drink it all the time? What’s the reason?” I tell them even the best troops in the whole world can do a lot, but if you are not feeding them, they become weak. These troops are fighting the bacteria in your body and they’re fighting nonstop, invisibly fighting bad bacteria in your body. People need to understand there’s no miracle. You can’t drink a glass or a liter and that’s all. You need to do it constantly and it will give you the health benefits from the nutrients and vitamins. I drink half a glass for my breakfast and and half a glass at night.

In kefir, your body assimilates the nutrients and vitamins. Sheep’s milk is easier to digest because it’s closest to mother’s milk, more than goat or cow milk — it’s a superior milk. You can even freeze this milk, we freeze it for the winter time and when you defrost it, it doesnt change the structure. The globule of the fat in sheeps milk is four times smaller than cow’s milk. It’s easiest to digest for people, especially with lactose issues. Same with our cheese made from kefir, it has the same benefits.

TFA: What about your other fermented products? Tell me about the baked milk yogurt.

SB: The baked milk yogurt can be confusing to people because they say “Doesn’t it kill all the probiotics in your yogurt?” No, we are slow cooking it, and then we add cultures. It is Russian and Ukrainian, this process of making yogurt. It goes back to history when people in villages were baking bread in a wooden oven. It was always pre-heated, they would put milk in a cast iron pot or clay pot. It would stay there overnight, and the water is evaporating and the milk sugar is caramelizing. We call it the healthiest creme brulee. It has the taste of caramel, but no sugar or caramel added because of the process of the caramelization of the lactose.

TFA: You make traditional yogurt, too?

SB: Yes, we are working with cultures from Italy. I tried to work with what’s available here, but it gave me a really sour, tart taste. It was too genetically modified, and that genetically modified culture is not allowed in Europe. We’re bringing all our cultures for our yogurt from Europe.

TFA: Tell me more about your cheeses.

SB: We do different varieties of cheeses called kefir cheese, we use zero commercial cultures. We are using only kefir. It takes more time, it changes a little bit of the taste for the cheese, but it’s the same culture. We’re able to produce fresh cheese to a few-years-old Pecorino. But it’s the same culture.

David Archer, he wrote The Art of the Natural Cheesemaker, I met him just before we started making kefir cheese. At that moment, his book had just released and people introduced us at the farmers market. He came to our farm and we spent a month together in our small-size commercial kitchen and creamery and he helped convert everything to kefir cheeses.

I’m always asking people just think about the history of the cheesemaking, cheesemakers they didn’t use the cultures from the lab, it was a natural fermentation. It was the same farm with the same bacteria, they’ve been doing different varieties of cheese, but it depends on your region because the environment is different. Sometimes, you don’t know what’s involved because the weather is different, the humidity is different and even our mood is different. If you’re not in a good mood, it comes out in the cheese.

Same with kefir cheese, we’re using the same kefir as a culture for our milk, and it gives us different results. Even with our soft-ripened cheeses, Camembert and Brie, the rind we are growing, it does not have any artificial bacteria that people put on top of the cheese to grow a rind. Kefir gives this ability to grow the rind naturally. But you need to be thoughtful and it involves a lot of labor because you need to keep your eye on the cheese everyday to see what’s growing on top. And you need to develop the right bacteria for the rind of the cheese.

TFA: Is the process to make a kefir cheese different from a traditional cheese?

SB: A little bit, but now much. The process to make it takes more time than traditional cheesemaking because you need to add kefir and wait. But it’s worth it because it’s a superior food that brings you all the good protein. It’s easier to digest compared to even meat because it’s naturally fermented.

TFA: How long did it take you to perfect these recipes?

SB: It’s an ongoing process. From the beginning I didn’t plan to do 25 cheeses. But I was surprised, people started asking me at the farmers market if I would make hard cheese. Now Pecorino is our top seller and our main product, it’s a sheep’s milk cheese made of full-fat, whole sheep’s milk.

Sometimes people are suspicious — “Oh a Russian, doing Pecorino in Canada?” But when they taste it, they love it.

Even as small producers, we are like big producers, because we are doing a big range of products. We have four more cheeses planned for the future. The sheep’s milk gouda is in the aging room now.

TFA: How does the taste of a fermented sheep’s milk product taste compared to fermented goat or cow dairy?

SB: Sheep’s milk is very sweet and high in fat, but good fat. It’s very smooth and creamy. My first impression when I tried a glass of sheep’s milk, it was like I was drinking the best cow’s cream of my life. It’s rich, but not heavy because the globule of the fat is very small. It gives richness, but at the same time, lightness. It’s so full of the different nodes of the taste. It’s sweet but not overly sweet, it’s balanced. The quality of the milk affects all the range of the products that we do.

Sheep milk is a very good balance between rich and light.This taste goes through the product. It’s totally different from goat milk, it doesn’t have a strong taste. Many people don’t like the taste of goat milk, the smell and taste. Sheep doesn’t have that strong taste at all.

TFA: I love that you are very invested in the welfare of your animals.

SB: For me the most important, I care how people are treating the animals. If the animals are healthy, free-range, pasture-raised, people are taking good care of them, they’re not giving them chemical-produced silo. We’re giving our animals fermented hay because it’s easier to digest. Year-round, our animals are grass-fed. We are not just farmstead producers, we are much more. Our main concern is the health of our soil. The quality of the product, the health of the product, it starts from the health of our lamb. Only good soil can guarantee good health for your animals.

TFA: Where do you see the future of fermented products?

SB: I believe in the future of fermentation. However, it’s not easy. For example, back in Russia, back in Europe, my family we’ve been doing sauerkraut since I can remember. Even here in Canada, living in downtown Toronto, even when we were in a condo, I was making sauerkraut. And kombucha.

But people are losing that connection to their food. They need the right guidance to reconsider their eating habits. I believe it will take some time to change, but we are optimistic.

- Published in Business, Food & Flavor

A Yeast Primer

Brewers, winemakers and cidermakers are continually on the hunt for the ideal flavor profiles for their fermented beverages. And the key to manipulating those flavors is yeast.

“With beer, you’re taking this kind of gross, bitter soup of sweet barley and hops, and the yeast makes it taste good. Depending on the yeast that gets put in it, it can make it taste like 400 different things, so there’s so much potential there. I think that’s really exciting,” says Richard Preiss of Escarpment Laboratories. Priess was joined by Doug Checknita from Blind Enthusiasm Brewing and Patrick Rue from Erosion Wine Co. to discuss the world of yeast in TFA webinar, A Yeast Primer.

“If you’re invested in vegetable fermentation, yeast might be sort of clouded in mystery and something that is unwanted,” says Matt Hately, TFA advisory board member who moderated the webinar. “It’s what you live by in beverage fermentation in wine and beer and it’s the key to unlocking flavors to make that magic happen.”

Domesticated vs. Wild Yeasts

Just as dogs and cats were domesticated by humans, yeasts have been as well, says Priess, whose company makes and banks yeasts. They are microscopic organisms that adapt, “so if someone’s making beer for over the span of hundreds or thousands of years then the yeast is going to change to kind of get better at fermenting that beer and maybe it’s not going to be so good at surviving out in the wild, just like our toy poodle versus our wolf.”

Other fermented drinks, like wine, sake and cider, use different yeasts with their own specific sets of traits. This is why a wine yeast can’t be used in a beer and vice versa, “though there are some opportunities to experiment.”

Fermenting with wild yeasts has become increasingly in vogue with beer brewers. Aspirational brewers are finding yeasts on the skin of fruit or the bark of trees.

The panelists on the webinar praise experimentation, but note there is risk. Priess says yeasts designed to survive in the wild can be challenging to use in a beer. Checknita points out the safety factor in using yeasts directly from nature as well, “you can get stuff that’s harmful to human health so you have to be careful with your pH levels and what controls there are.”

Traditional winemakers, on the other hand, have long used the wild yeast on grapes to ferment. Rue notes that 10 years ago winemakers began to deviate from this tradition to use pure cultures instead. This process is how many large-scale, industrial producers operate today. But smaller winemakers, who often want to emphasize the specific traits of their terroir, generally use native yeasts and traditional winemaking techniques.

“It’s amazing how wine is how God intended wine to be made because you let nature happen and you’ll probably have a pretty good result with natural fermentation,” Rue continues, “where beer, it’s very touch-and-go, you have to have the perfect conditions and I’ve been able to do spontaneous fermentation with those yeasts.”

The Yeast Family Tree

There’s a large and continually-growing family tree of yeasts, with branches forming for genetic diversity and specialization.

Priess sees three new trends emerging in yeasts: traditional yeasts (like Norwegian kveik) being rediscovered, yeast hybridization (similar to cross-breeding a tomato) and genetic engineering to enhance certain traits of yeast.

“That’s the exciting part of what we’re doing is no one really knows the best approaches to using beer yeast yet, but there’s a lot more new science that’s happening, a lot more brewers that are experimenting, and together we’re collaborating to understand how to work with yeast better and kind of unlock new flavors and new possibilities,” Priess says.

Checknita agrees. He says new yeasts are forming new family trees through spontaneous fermentation, which is taking the base of a beer and experimenting to “push and change those yeasts to do what we want and get that clean flavor that’ll make a beer that tastes good to the human palate.”

- Published in Food & Flavor

Bubbling Over: Why Kimchi Is the Fastest-Growing Fermented Veggie in America

Sales are soaring. Although kimchi only makes up 7% of the pickles and fermented vegetables category, its sales are increasing at an explosive 90% rate, according to SPINS.

We asked three kimchi experts their thoughts on the uptick in sales: Minnie Luong, founder and CHI-EO of Chi Kitchen, JinJoo Lee, chef and Korean Food Blogger at KimchiMari and Kheedim Oh, founder and Chief Minister of Kimchi for Mama O’s (and member of TFA’s Advisory Board).

We asked them: Why do you think kimchi sales are increasing so rapidly?

Minnie Luong: Originating in Korea around 4,000 years ago, kimchi is an iconic food symbolic of hope, trust, and survival that is the perfect food for our current times. One of the world’s most special foods, it elicits delight, storytelling and sharing. In fact, UNESCO has designated kimjang — the traditional way of making and sharing kimchi — a designated intangible cultural heritage of humanity.

Low in calories, high in fiber and big on flavor that’s great for your digestion and gut health, kimchi is uniquely poised to cross over from being a specialty food to a must-have pantry staple for health and wellness enthusiasts, home cooks and those seeking out a satisfying flavor adventure. Its spicy, tangy, umami flavor is convenient and easy to use across a wide range of dishes along with a long shelf life when refrigerated. Just open a jar and it’s ready to go! While kimchi is often seen as a condiment, it should really be considered a vegetable, but one that packs a delicious, probiotic punch. Let’s face it, we could all use more veggies and flavor in our lives!

JinJoo Lee: I think the sales of kimchi are increasing because more and more people are aware of the health benefits of kimchi (loaded with probiotics like many fermented foods) and also are being introduced to the wonderful flavors of it now through many restaurant foods and magazine recipes.

More restaurants have started to use kimchi in their menu because I think chefs have realized kimchi works great in non-Korean dishes such as on hamburgers, pasta, cheese quesadillas and even with Brussels sprouts!

Kimchi has a very deep and complex flavor with an amazing zing that fermented foods have but it also is a perfect balance of sour, spicy, salty, umami and slightly sweet that works well with so many different foods, especially meats and seafood.

Most Americans may know only the spicy napa cabbage kimchi (Baechu Kimchi) but did you know there are over 100 different kimchis? kimchi can be made using all sorts of different vegetables such as cucumber, eggplant, radish, mustard greens, green onions, chives and more.

If made and stored properly, kimchi can last for weeks, months and years and it can be enjoyed throughout all the different stages of fermentation – from the very beginning as fresh tasting to fully ripe to overly ripe and sour then even when it’s aged for years! So kimchi is the perfect fermented food that’s tasty, healthy, versatile and even long-lasting.

Kheedim Oh: With everyone in the world simultaneously experiencing sensations of uncertainty mixed with mortal fears of peer contact, people are drawn to the near mythic powers of kimchi. One of the top 5 healthiest foods in the world (according to Health Magazine). A true superfood. People are attracted to the promises of probiotics. The comfort of supporting their immune systems with each bite. The flavor of fermentation. The addictive nature of how eating good kimchi makes you feel.

The word kimchi has reached a tipping point where it’s no longer just the stinky rotting cabbage from Korea (or wherever) to the acidic/tart vegetable dish that “I had as part of a dish at the insert [trendy fusion restaurant] that I went to and I heard it’s really good for you.” It’s losing its Korean-ness and quickly being subsumed into White American food culture the way that kombucha has already completely become. There are a lot of “kimchis” that are only kimchi through very loose interpretations or are just not real kimchi by any definition, only by name. The culprits being many of the before-mentioned fusion restaurants.

On the other hand, there is the whole DIY home fermentation movement that has been growing year over year. Educating themselves on how to achieve food sovereignty, they tend to be a more culturally sensitive crowd. Regardless of the hype surrounding the word, we hope that kimchi can maintain its popularity in America while maintaining its unique UNESCO World Heritage recognized cultural identity as a Korean food.

- Published in Business, Food & Flavor

Building a Fermented Brand

Behind every fermented food or beverage is intriguing science that creates a pleasantly tangy taste. Customers want to know all about that chemical process, right?

No. Stop geeking out and appeal to the foodie instead.

“This is about the joy of eating, and so when you over-science me and you over-gut me, I forget the joy of eating. Remind yourself that your most important message is how pleasant, how tasty, how engaging, that’s the pleasure of eating, and then you can tell me how you make that pleasure,” says Sasha Strauss, managing director at Innovation Protocol (a marketing consulting & design agency). Strauss shared his brand strategy tips in the TFA webinar Building a Fermented Brand. He stressed fermented brands need to avoid getting stuck in the “scientific nuance of how you make your products. I’m not saying delete the science, just don’t make it the marquee.”

Alex Corsini, founder of frozen pizza company Alex’s Awesome Sourdough (and TFA Advisory Board member) agrees. Corsini, who moderated the webinar, says he began his brand with a heavy emphasis on the science of fermenting sourdough.

“Our customer didn’t really respond to that. And that’s something I see in fermentation all too often, is people aren’t selling the actual benefit. They want to understand the benefit, so that’s what you lead with,” Corsini advises.

If you’re selling kombucha, for example, share that it’s a feel-good product that will make you feel better than a soda, Corsini says. Don’t make your selling pitch the SCOBY’s technical specifications.

Teach, Don’t Sell

“I don’t understand fermentation. I don’t understand the health benefits. I don’t understand its cultural origins. I don’t understand what section to buy it in. I don’t understand what to eat it with or who to serve it too. Your first duty as a brand is to help me make sense of this, help me understand it,” Strauss says. “It’s not your job to be the sexiest, raciest, the most innovative, it’s your job to help me understand. And where understanding sits in the consumer’s mind is where buying behaviors originate. So the first and most important duty of your brand is to simply help me not feel alone, help me not feel confused, help me not feel overwhelmed.”

By educating the consumer, by inspiring them to learn about fermentation, “they will be indelibly connected to you,” Strauss continues. “They will prefer you. They won’t wonder if your price is a penny cheaper, they’ll prefer you because you’re who they learned from. We buy who we learn from.”

There’s not enough room on a label to detail all the health benefits or the scientific details of a product. But this information can go on a brand’s website, social media page or table-top display at a trade show or farmer’s market.

“I hope that your audience doesn’t hear from you just once,” Strauss says. They should find a video of your product on Instagram, find recipes on your website and see an ad in the local paper. Brands need to create multiple opportunities to engage, “don’t try to cram all of your value in a single channel.”

A New Economy

The COVID-19 pandemic has permanently changed the economy. Consumer lifestyles have changed, too, and these new behaviors create opportunities, especially for fermented products that are healthy and flavorful.

“Historically, if you were trying to build a consumer packaged goods brand, it was really about your resume, your long list of accomplishments , your heritage in farming, your understanding of the chemistry and that was what marked the person, the business, the brand,” Strauss says. “But actually now, it’s really about how you resonate, how I connect with you, how you inspire me, and that doesn’t require a long history, that requires a contemporary participation.”

“In a world where the audience is starting and ending their search digitally, each of the things that you share, post, write about, blog about, video dialogue about, those things are little breadcrumbs that will never go away,” Sasha says. “They’re little trails that lead to your brand, lead to your resources, lead to your understanding and this is powerful.”

Consumers rejected traditional brand loyalties this past year. They’re increasingly open to new brands, curious about new cultural flavors and want healthy food. Critically, Strauss points out, they want to purchase from socially responsible brands. “In a post-covid era, we want a brant to also do good,” he says.

Producers must make conscious choices about the farmers they use — how are they improving soil health? What is the environmental impact of their distribution line?

“Understand you have to make an impact, somehow do good for the world while building business,” Strauss says.

- Published in Business