The State of the Art in Coffee Fermentation

More specialty coffee producers are developing unique approaches to their coffee bean fermentation, isolating native microorganisms to create a flavorful cup or working closely with rural farmers to utilize fermentation control techniques on small-scale operations.

“Practically all the coffee we drink has been fermented in one way or another. But there is huge room for improvement, innovation and development in the realm of coffee fermentation,” says Mario Fernández, PhD, Technical Officer with the Specialty Coffee Association (SCA). The SCA partnered with The Fermentation Association for the webinar The State of the Art in Coffee Fermentation.

Fernández continues: “Coffee is produced by millions of small coffee producers around the tropics that have very little capital to invest in fermentation equipment. Oftentimes, the price is too low for them to add fermentation controls as part of the cost equation. Therefore, for perhaps 99.9% of coffee in the world, it undergoes wild fermentation, in which the microbes grow on the mass of mucilage in a wild fashion and the coffee producer only controls certain parameters, such as the length of the fermentation.”

Two industry experts on the forefront of coffee fermentation technique and technology joined Fernández — Felipe Ospina, CEO of Colors of Nature Group (multinational specialty coffee trader) and Rubén Sorto, CEO of BioFortune Group (a coffee, upcycled and food ingredient manufacturer based in Honduras).

Post Harvest Processing Technology

Sorto is adapting fermentation technology to coffee, mapping the microbiota of the bacteria and yeasts that are present at Biofortune Group’s farms.

“We realized that fermentation was one of the key aspects of the coffee production that hadn’t been addressed,” Sorto said, noting fermentation is controlled in industries like dairy, wine, beer and bread but not in coffee. “We learned that our soil, our water, our coffee trees, our leaves, our [coffee] cherries, had a large compendium of bacteria and yeast that were involved in the posterior fermentation process…some of the yeasts and bacteria were definitely beneficial and were urgently needed during the fermentation but some of them were not.”

To maximize flavor, they focus on that complex array of bacteria and yeasts, preferably indigenous to the countries of origin. These microorganisms thrive in their local environment, reflecting altitude and temperature. To control the fermentation of those bacteria and yeasts, Biofortune reduces the variables, including monitoring pH levels, alcohol content and container contaminants.

“If you are able to control the fermentation, you are also able to offer a higher-quality product, a consistent quality product…and that’s what the market is looking for, consistent quality in a cup,” Sorto says.

Educating Coffee Farmers

Ospina, meanwhile, is researching fermentation techniques accessible to small-holder coffee producers and training them. The goal is for them to understand the role of each microorganism, discover how to use it in fermentation, then scale that knowledge to small-scale operations, so they can produce incredible coffees.

At La Cereza Research Center, the Colors of Nature facility in southern Colombia, they are experimenting with fermentation processes. Some alcoholic fermentations result in coffees that produce coffees that taste of whiskey, cognac, champagne, sangria or even beer. Lactic fermentations might produce coffees with flavors of banana, mango, papaya, grapefruit or even cacao. “This is showing us the potential is humongous,” Ospina says.

“Wild fermentation is the ultimate expression of the terroir and it’s very important for us because the terroir produces unique coffees,” Ospina says. “The thing is, we don’t understand wild fermentation yet, but I’m very against demonizing wild fermentation. Why? Because we have seen hundreds and hundreds of outstanding, amazing coffees from all over the world that have been produced with wild fermentation.”

There are challenges. Food safety is a big concern. Ospina teaches the use of disposable gloves at the farm level to prevent contaminants, and to put a new plastic bag in the bioreactor for each batch of beans to avoid cross-contamination.

The cost of implementing fermentation technology can be high. Sorto recommends to start by buying each farmer a pocket pH meter and a refractometer to closely monitor the fermentation.

“Translating science and technology to small farmers with very little investment will help them increase the possibility of a higher income because if you are not able to control fermentation, you are risking the effort of a one year harvest,” Sorto advises.

- Published in Business, Food & Flavor

Beyond Kombucha: Pu’erh, Jun and Dark Tea

Tea consumption globally is increasing. But consumers don’t want a cheap, poor quality tea bag. They’re buying premium teas — and increasingly, dark, fermented teas.

“What’s trending right now seems to be authentic tea, tea that has great flavor, more closely married to the terroir. People are beginning to understand that it’s just fine to have tea. You don’t have to have coloring in it, you don’t have to have a lot of bits and pieces of fruit and flowers, there’s a genuine benefit to just understanding the terroir and keeping it simple,” says Dan Bolton, the founder, editor and publisher of Tea Journey. Bolton and two tea experts discussed two lesser-known fermented tea varieties in the TFA webinar Beyond Kombucha: Pu’erh, Jun and Dark Tea. “Tea just isn’t as good as it could be, without fermentation.”

A new study on tea demonstrates how important fermentation is to tea quality, Bolton says. Researchers from the Anhui Agricultural University in China recently studied the effect of surface microbiomes on the quality of black tea. The results found microbial fermentation in non-sterilized control tea samples produced complex compounds and more flavorful teas than with sterilized tea leaves. The results were published in the Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry.

“It’s a remarkable finding because, certainly for the last century or so, there’s been a lot of discussion about whether fermentation plays a role in the production and processing of tea,” Bolton says. The study proves “black tea is actually a result of both fermentation and oxidation.”

Pu’erh Tea

Jeff Fuchs — author, Himalayan explorer and co-founder of Jalam Teas — shared details of pu’erh tea. Pu’erh is a tea style from a strain of camellia leaf cultivated and produced in the Yunnan province. Fuchs spent over a decade living in there and is the only Westerner to have traveled the Tea Horse Road through Sichuan, Yunnan and Tibet.

“Pu’erh is a tea that certainly I think it’s been deliberately mystified to some degree,” Fuchs says. “It’s interesting that you have this very simple, raw material green tea that is now arguably one of the great boutique commodities.”

Fuchs stresses consumers need to research tea sourcing. Where is the tea coming from? How was it stored? Who stored it? Older tea cakes are being sold for large amounts of money, but can have questionable provenance.

“Young teas I think are making a big assertion in the tea world right now because they represent a closer line to the terroir, a closer line to the origin point,” he says, adding dark teas are becoming more popular in North America. He sees more bartenders experimenting with dark teas, playing with flavor compounds. “I think dark teas will come into the sway more and they’ll remain.”

Jun Tea

Jun is another tea style making waves in the fermented beverage market. It is a type of kombucha, but the base is green tea and honey instead of black tea and sugar. Brendan McGill shared his experience making jun — he is a chef and James Beard nominee; he owns the Hitchcock Restaurant Group in Seattle and the newly-launched Junbug Kombucha.

“Jun is a very special style of kombucha,” McGill says. “It’s shrouded in mystery, where these cultures originated. What we do know is how they’ve been developed and manipulated in fairly recent history. One of the joys I’ve had with this is just being extremely creative because i found that while the fermentation isn’t necessarily a delicate process, it has allowed us to modify and use a lot of different inputs that it’s actually a pretty robust fermentation process.”

McGill began making kombucha over a decade ago, as a replacement for beer and wine. He liked jun for its similar flavor to alcohol, the additional bioactive compounds that create a more nutritious drink and it’s made with honey instead of added sugar.

Junbug Kombucha uses filtered water, organic green tea, wild honey and, of course, a SCOBY. In the secondary fermentation, fresh herbs, berries and even mushrooms are added. Junbug flavors include Chaga Root Beer, Chili Raspberry and Maui Mana.

- Published in Business, Food & Flavor

Q&A with Jessica Alonzo of Native Ferments TX & Petra and the Beast

Cheffing is a second career for Jessica Alonzo. Originally a hospital administrator in Dallas, she liked the stability and the benefits, but wasn’t happy. She longed for the days around the kitchen table with her mom, cooking for large family gatherings — “I have such fond memories of food.” Hospital pay got her through culinary school, and then she joined the acclaimed Dallas restaurant FT33 as a line cook. It was there that she got introduced to fermentation.

“With fermentation, the transformation of ingredients is just insane,” Alonzo says. “Fermentation is not new, it’s something that we’ve been doing for thousands of years. It’s a lost art and now it’s starting to make a resurgence.”

Fermentation and whole food utilization are Alonzo’s specialty. Whole food utilization, the cooking technique of using the entire animal or produce, marries perfectly with fermentation. Instead of discarding food scraps, skilled chefs are using the byproducts in brines, condiments and sauces.

“I preserve with a purpose,” says Alonzo, a Texas native. “I’ve worked with farmers long enough to understand what works with their produce throughout the year and what doesn’t. I’ve harvested with them, I’ve worked on their land. It plays a big role in fermentation to know how to properly preserve what farmers are harvesting.”

Alonzo is the sous chef at Dallas-based Petra and the Beast, a James Beard Award semifinalist known for its seasonal tasting menu. She stepped back to part-time status this year and launched her own business, Native Ferments TX, a larder shop that sells local ferments and offers virtual fermentation classes. Below are highlights from TFA’s interview with Alonzo.

The Fermentation Association: Tell me where the idea for Native Ferments came from.

Jessica Alonzo: Misti (Norris, chef/owner at Petra and the Beast) and my husband really pushed me to do it. They were like “You have the drive, you have the knowledge — why not share that talent with others?” People are always messaging me on Instagram asking me about different fermentation methods, and now I can teach them through classes. I love fermentation, I’m just fascinated with it, and it’s just continuous learning for me. You feel like you never really learn everything with fermentation, there’s so many different types of cuisines and techniques.

TFA: Why is it so important to you to support local farmers through fermentation?

JA: With both Native Ferments and Petra and the Beast, I get to work with farmers and support them, which is really what I love doing. Noma is helping make fermentation popular again, opening people’s eyes to the fact that fermentation has been happening forever. Fermentation is not new, there’s a tradition to respect. It was done back in the day because of necessity, people had to figure out how to save their harvest, and fermentation made it so they’d have the nutrients from their harvest throughout the rest of the year.

During the pandemic, restaurant sales for farmers dropped off drastically. At Petra, we had one of our farmers come to us with like a hundred pounds of mushrooms they couldn’t sell and they were going to go bad. I preserved them and made mushroom conservas and dried and did all these things with it, and then we ended up selling some of the mushroom pickles and conservas. I don’t know if any other restaurant did that in Dallas. It forced us to be really creative with food.

On my website for Native Ferments, I have profiles of the main farmers I use. When I sell at farmers markets, I have a big board with their Instagram handles. It’s their livelihood, I don’t want any of their produce to go to waste or to compost, I want the community to enjoy it. The magic of fermentation is transforming these simple ingredients with the natural microbes around you. I’ve worked with many of these farmers long enough to know what type of technique works well to pickle or ferment. I want to help educate people and get them excited and spread the word about the farmers’ hard work.

TFA: Tell me more about whole food utilization.

JA: At Petra, Misti was more the meat charcuterie person. She knows how to utilize every part of a pig or an animal. My mind goes more to vegetables, which I think is why we make such a good team. It makes sense that whole food utilization and fermentation go hand-in-hand. It’s part of preserving. We may be prepping something for tasting and then we have like carrot scraps or like some sort of vegetable or fruit scraps and we’ll automatically turn that into a vinegar. Or we dehydrate our char and dehydrate skins and turn that into part of a seasoning for another dish. Or I’ve done like roots from spring onions, I’ll brine those or I’ve chopped them up and parts in a condiment. We try to be as low waste of a kitchen as possible.

I do that with my ferments here with Native Ferments, too. In my fennel kimchi, I use the entire part of the fennel in that fennel kimchi, the fronds, the stems, everything, and then if my ratios were a little different so I did have some fronds left over, I dehydrate those and make that into a powder and now i’m utilizing that powder into a cure that I’m using on carrots for vegetable charcuterie. Understanding flavor profiles, too, helps when you’re cross utilizing your larder.

TFA: So tell me what have been some of your favorite fermentation creations you’ve been working on lately.

JA: Vegetable charcuterie is pretty cool, I’ve gotten some local produce in different root vegetables and I’m working on different charcuteries with more whole utilization in the curing. So like using the fennel from powder for part of the cure with carrots. I’m doing some shiro shoyu for another chef here in town and gluten-free shoyu for myself. I just smoked some beets and I’m pickling them in a shio koji that I made with a half sour brine and some spring onions. I’m hoping it takes on a meaty, smoky-like brisket, I was really craving barbecue when I did it.

TFA: Why do you think fermentation has become such a bigger interest among chefs?

JA: I think chefs are understanding the importance of the different complexity that you get when you build with fermented food in your cuisine. When Misti and I create dishes at Petra, we always in every dish that we create have some sort of pickle or ferment. Whether it’s an actual fermented vegetable or it could be an amino sauce that I’ve made or a shoyu or using shio koji or something, you don’t get that same transformation just by sauteing vegetables. You see the transformation by marianating them in shio koji first or using a brine in your pasta sauce rather than using a lemon juice. That’s how you build on these complex flavors. Some chefs are really trying to understand that. Utilizing fermented foods in their cuisine, being more creative with their flavor profiles, that’s what we do.

TFA: What do you think is the future of fermentation?

JA: With the resurgence of fermentation, I think it’s going to be more accepted in every household. I would hope that it would be something that every household would have. My parents grew up in the ‘60s, when everything was in a can. We had our traditional Mexican food, but we also had those times where it was Americanized, like everything in a canned food. Fermentation, this really should be the norm. Consumers need to be more aware of how beneficial it is

- Published in Food & Flavor

Managing Fermented Food Microbes to Control Quality

Fermented foods are produced through controlled microbial growth — but how do industry professionals manage those complex microorganisms? Three panelists, each with experience in a different field and at a different scale — restaurant chef, artisanal cheesemaker and commercial food producer — shared their insights during a TFA webinar, Managing Fermented Food Microbes to Control Quality.

“Producers of fermented foods rely on microbial communities or what we often call microbiomes, these collections of bacteria yeasts and sometimes even molds to make these delicious products that we all enjoy,” says Ben Wolfe, PhD, associate professor at Tufts University, who moderator the webinar along with Maria Marco, PhD, professor at University of California, Davis (both are TFA Advisory Board members).

Wolfe continued: “Fermenters use these microbial communities every day right, they’re working with them in crocks of kimchi and sauerkraut, they’re working with them in a vat of milk as it’s gone from milk to cheese, but yet most of these microbial communities are invisible. We’re relying on these communities that we rarely can actually see or know in great detail, and so it’s this really interesting challenge of how do you manage these invisible microbial communities to consistently make delicious fermented foods.”

Three panelists joined Wolfe and Marco: Cortney Burns (chef, author and current consultant at Blue Hill at Stone Barns in New York, a farmstead restaurant), Mateo Kehler (founder and cheesemaker at Jasper Hill in Vermont, a dairy farm and creamery) and Olivia Slaugh (quality assurance manager at wildbrine | wildcreamery in California, producers of fermented vegetables and plant-based dairy).

Fermentation mishaps are not the same for producers because “each kitchen is different, each processing facility, each packaging facility, you really have to tune in to what is happening and understand the nuance within a site,” Marco notes. “Informed trial and error” is important.

The three agreed that part of the joy of working in the culinary world is creating, and mistakes are part of that process.

“We have learned a lot over the years and never by doing anything right, we’ve learned everything we know by making mistakes,” says Kehler.

One season at Jasper Hill, aspergillus molds colonized on the rinds of hard cheeses, spoiling them. The cheesemakers discovered that there had been a problem early on as the rind developed. They corrected this issue by washing the cheese more aggressively and putting it immediately into the cellar.

“For the record, I’ve had so many things go wrong,” Burns says. A koji that failed because a heating sensor moved, ferments that turned soft because the air conditioning shut off or a water kefir that became too thick when the ferment time was off. “[Microbes are] alive, so it’s a constant conversation, it’s a relationship really that we’re having with each and every one on a different level, and some of these relationships fall to the wayside or we forget about them or they don’t get the attention they need.”

Burns continues: “All these little safeguards need to be put in place in order for us to have continual success with what we’re doing, but we always learn from it. We move the sensor, we drop the temperature, we leave things for a little bit longer. That’s how we end up manipulating them, it’s just creating an environment that we know they’re going to thrive in.”

Slaugh distinguishes between what she calls “intended microbiology” — the microbes that will benefit the food you’re creating — and “unintended microbiology” — packaging defects, spoilage organisms or a contamination event.

Slaugh says one of the benefits of working with ferments at a large scale at wildbrine is the cost of routine microbiological analysis is lower. But a mistake is stressful. She recounted a time when thousands of pounds of food needed to be thrown out because of a contaminant in packaging from an ice supplier.

“Despite the fact that the manufacturer was sending us a food-grade or in some cases a medical-grade ingredient, the container does not have the same level of sanitation, so you can’t really take these things for granted,” Slaugh says.

Her recommendations include supplier oversight, a quality assurance person that can track defects and sample the product throughout fermentation and a detailed process flow diagram. That document, Slaugh advises, should go far beyond what producers use to comply with government food regulations. It should include minutiae like what scissors are used to cut open ingredient bags and the process for employees to change their gloves.

“I think this is just an incredible time to be in fermented foods,” Kehler adds. “There’s this moment now where you have the arrival of technology. The way I described being a cheesemaker when I started making cheese almost 20 years ago was it was like being a god, except you’re blind and dumb. You’re unleashing these universes of life and then wiping them out and you couldn’t see them, you could see the impacts of your actions, but you may or may not have control. What’s happened since we started making cheese is now the technology has enabled us to actually see what’s happening. I think it’s this groundbreaking moment, we have the acceleration of knowledge. We’re living in this moment where we can start to understand the things that previously could only be intuited.”

- Published in Food & Flavor, Science

Redzepi: We Need Restaurants to “Feel Alive”

Restaurants have been under tremendous economic pressure, suffering from business losses during the Covid-19 pandemic. And there’s now a staffing shortage, as long hours and low pay have driven many away from the industry.

Bloomberg columnist Bobby Ghosh explored how restaurant dining may change in an Instagram live interview with Rene Redzepi, owner and co-owner of Noma, Copenhagen’s two-Michelin star restaurant world-renowned for its experimental fermentation lab. Pandemic restrictions shut down Noma twice, forcing Redzepi to create additional revenue streams outside the traditional dining room.

In the summer of 2020, Noma opened an outdoor, walk-in burger and wine bar. Earlier this month, they announced Noma Projects, a direct-to-consumer line that will initially sell garums.

Below are highlights from Ghosh’s interview with Redzepi.

Ghosh: What did you learn about how people were feeling about returning to restaurants?

Redzepi: Restaurants, you don’t need them to stay alive but you need them to feel alive. That was very, very clear, that people were ready to go out. You know they say it’s the catch-up effect, and that definitely happened here in Copenhagen. People were everywhere, they were in piles to get a bite to sit down, have a glass of wine and meet other people.

Ghosh: When you began to think about reopening the proper dining space and planning your menu for the reopening, did you have any particular thoughts or concerns about whether people’s habits in restaurant dining might have changed in the course of the year that they were all locked up?

Redzepi: Yeah, so we went through the first lockdown, opened up, we were open for about five months and then it all came back and we had to close (again during the second lockdown). On the second lockdown, we were shut for six months and, in that time, we were very worried about everything, I mean we still are, but I guess we’re a little less worried now than before because we’re finally open again. We did think “Would people even sit for hours in a restaurant? What is it that everyone wants?” Besides that, people in Denmark, they started really cooking at home again. Takeaway offerings had become quite common, even from some of the best restaurants, something that would be considered completely impossible five years ago. If you had takeaway as a fine dining establishment, you sort of sold out in a way and that was starting to happen.

But I decided with myself, and that was a personal decision, is that in my life I need this creativity, I need to have guests, I need to work on a menu on a daily basis, so during the lockdown I went to work every day in the kitchen as if we were going to open the following day. We actually made two full menus and one of them will never be served because we ended up being closed throughout it. And then we said “OK, let’s just open up and see what happens, will people still want to come out?” and we opened up our reservations knowing that we would cater only to 100% local crowd and it’s gone really well, really really well.

Ghosh: The thrill of being in a nice restaurant and being able to talk to people and enjoy a meal is incomparable um and I do appreciate the value of fun after the year and a half that we’ve all had. Can you give us an example of a dish that you have in your menu now that reflects this attitude of fun, the surprise.

Redzepi: Swedish saffron believe it or not, it’s really, really strong and tastes amazing. We make this fudge with it and we found out that you can actually use the sort of the cutting of walnut as a wig for candles because the oil content in the walnut makes it flammable. And so we basically shaped or molded this little toffee into a candle. It sounds complicated but it’s quite easy to do when it’s hot and then we put this walnut light into it and it comes to the table when they’re drinking coffee and people think it’s you know for coziness and then as it burns out people are then instructed to eat it that’s a that’s a moment where that’s fun you know it’s creativity, it’s delicious it surprises people and it just really makes it makes a difference to people you can feel that they’ve been needing something like that.

Ghosh: What have you learned that you didn’t already know about restaurant economics over the past year that now factors in your thinking about what Noma is and what Noma needs to be in the future.

Redzepi: Oh man, you’re hitting something that we’ve been talking about for the past two years because, particularly in the last year-and-a-half, restaurant economics, they’re terrible. We’ve had 18 years of operation and we’ve had an average profit of 3%. It’s just enough to keep us running and keep painting the house, so during this pandemic we did think to ourselves “Are we going to continue like this for another 18 years, where we don’t have any money to change anything, even if we want it?” You know we’re going to have to find different ways of operating so that we can have a different economics in it. We have to figure out a way if we want to be here for another 18 years because you know it won’t continue like this. So we have definitely thought of many many things and recently we launched this thing that we call Noma Projects. Noma Projects is a sort of a platform to launch a myriad of things, it’s a for-profit company, but we only want to attack projects that also connect to some sort of a worldly issue, and the first project one is is a vegan and a vegetarian garum sauce that you use as a flavoring to add umami to your vegetarian and vegan cooking. It’s a way to help people eat more vegetarian so that’s project one, that’s something that we worked on almost almost since the first lockdown that happened to us we were like we need to step into this.

Ghosh: About six months ago, I did a piece about restaurant economics and the pandemic. I talked to your friend David Chang of Momofuku. We’re saying that we have to figure out more ways to find revenues outside of the dining room. You know, can we get 50% of the revenue from outside of the dining room where the margins are larger to sustain, to underwrite the amazing creativity that goes on in your kitchens? Is that possible? Have consumer tastes or consumer behaviors now changed in a way that will allow that kind of thing?

Redzepi: I think what happened during the pandemic is that it’s been considered more OK for restaurants of say Momofuku caliber or Noma to actually think of ways to put better economics into the system. That has opened a new door and for us, we’re grabbing that opportunity, we need to, definitely. Our industry needs to, in general. It’s an industry that’s under copious amounts of pressure, we deal with poor profit margins, low incomes, people are overworked, they’re underpaid, there’s bad management and a lot of it is a result of there’s simply no money in the industry, people can’t afford to do maneuver any new way they want, and we don’t have any business training either. It’s very interesting what’s going on. I think a lot of creativity is going to come out of restaurants in the next couple of years.

Ghosh: Now in addition to being a chef, you’re a thinker in your line of work. Through MAD Academy, which used to be anyway your annual gathering of of great chefs from around the world, you’ve spent a lot of time thinking about your industry and the future of your industry. I imagine that during the course of the past year, year-and-a-half you’ve had many conversations with the kinds of people who would previously have come to that conference. What are some of the common themes, the common challenges for fine dining establishments?

Redzepi: I think in food in general, the most common problem, and I think it’s going to continue for a while, is that there’s a gigantic staff shortage right now. I think in the pandemic, a lot of people have had an opportunity to rethink their life and say “OK, am I in this industry for the next 20 years or is this a moment for me now to start studying or become a farmer or something else.” That is really the biggest issue that we have right now, there’s no question in my mind. This is something that at MAD we’ve been discussing for almost a decade. If we’re not able to help transform (and this includes myself by the way I’ve spoken about this many times) this gigantic lack of leadership that we face as an industry where we have a poor ability to actually just manage ourselves, manage our restaurants and be supportive of people, that will be the first step that needs to happen which is slowly happening. But then providing better pay and better work hours, that are related to economics. I see our industry being far from that, unless we figure out a way to either charge more that there’s more value towards foods and people that work in the industry or we find other revenue streams. Those are the big, big questions that we are dealing with at MAD. At Noma, I deal with this as a employer myself, how to actually be an inspiration, but how to also provide for staff that are having children, and how can we have everyone stay here for 40 years in this industry? That’s really hard questions.

- Published in Business

Noma Goes DTC

Noma is coming into the home kitchen.

The fermentation-focused restaurant, lauded as one of the top restaurants in the world, is selling its first line of packaged products. Two garums — vegan Smoked Mushroom and vegetarian Sweet Rice and Egg — will soon be available to ship internationally through the brand’s website, Noma Projects.

“It’s a space for us to channel our knowledge, our craft and experimentation into a new endeavor,” says René Redzepi, chef and co-owner of the Copenhagen-based restaurant.

Redzepi shared details of the launch in a video on the site. Noma Projects will include pantry products and community-based initiatives, “a way for us to address issues we care about through the lens of food.”

Noma’s Pantry Staples

The garums are Noma’s “take on a 1,000-year-old recipe that we’ve been developing over the past two decades.” Redzepi says the “potent, umami-based sauces” have been the “key to our success at Noma in our vegetarian and vegan menus.

He hopes the garums will help more people cook plant-based meals, announcing in the video: “We want to help you bring more vegetables into your everyday cooking.” The garums provide the flavor of meat and fish without the animal. The website description notes: “Shifting towards a more plant-based diet is the easiest way for an individual to help the environment. We hope these garums will do the same for you that they’ve done for us, help inspire and create more delicious plant-based meals when you cook at home.”

These products were developed in Noma’s Fermentation Lab, where dozens of pantry staples were tested before landing on the garums. A garum is the “concentrated essence of its main ingredient” with a strong umami flavor, and Redzepi describes it to the WSJ. Magazine (the luxury magazine published by Wall Street Journal): “It has the potency of a soy sauce, except it tastes of what it is.” Both are brewed with koji rice, what Redzepi calls the “mother fungus.”

The garums are currently fermenting and will be ready for shipping in the fall or winter. The expected price point is $20-$35 for a bottle.

And more garums are in the works. Noma Fermentation Lab director, Jason Ignacio White, says a roasted chicken wing garum is next.

“It tastes like super chicken stock with umami,” White tells WSJ. Magazine, ”so it’s a familiar flavor, but there’s something about it that you can’t really put your finger on, that makes your tongue dance.”

Improving Profitability

Despite Noma’s expensive tabs — the 20-course tasting menu costs 2,800 Danish kroner (or around $447), and the wine pairing is another 1,800 Danish kroner (or around $287) — in the 18 years since it opened, the restaurant has hovered at only a 3% profit margin. Redzepi hopes Noma Projects will make more money. While it is “a family-run garage project,” its goal is to reach a million customers.

Like many restaurants around the world, Noma shut down during the pandemic. They reopened as a burger and wine bar in June 2020, and the walk-up, outdoor dining experience was such a success that it became a permanent restaurant, POPL.

Noma resumed regular operations on June 1, 2021. The pandemic closure allowed Redzepi and his team to finally tackle the retail brand, something he said they had debated for years.

- Published in Business, Food & Flavor

Best Practices for Cash Flow Management

Running a food or drink business is challenging in today’s market — there’s increasing competition, fast-paced trends and challenging access to retailers. If you run a fermentation-based business with a long production cycle, those market forces are compounded.

“A lot of businesses in this sector are in it because of the passion, they love what they’re doing, and sometimes the finances can feel very mysterious, there’s an aversion to dealing with it, and they aren’t taking the time to really look and understand the numbers,” says Maria Pearman, a principal with Perkins & Co., Portland, OR-based professionals in food and beverage finance and accounting. She shared her expertise during a TFA webinar, Best Practices for Cash Flow Management.

“Cash flow forecasting, it’s not rocket science. It’s not hard stuff. It is just very foreign to a lot of people and they avoid it,” Pearman says.

Matt Hately, a TFA Advisory Board member who moderated the webinar, agreed. Hately is an investor and advisor in fermented food and beverage brands.

“Managing cash…I would argue that it’s even more of a challenge for fermentation companies where your production cycles aren’t instant, they might take a week or three weeks or six weeks and, when you’re starting, your suppliers are probably demanding to be paid up front, your customers want 30-day terms,” he says .

Fermented Financials

Pearman, author of the book Small Brewery Finance, shared an overview on cash management. Fermentation businesses need to closely manage their cash conversion cycle as production cycles lengthen. The cash flow conversion cycle is the period between when money is spent to purchase ingredients to when payment is received from the sale of the final product.

Fermented products — which can take anywhere from a few weeks to even years to ferment — have a long cycle.

Pearman shared the example of a whisky distiller. After fermentation, whisky ages in barrels for years. All the while — before the product is ever sold — there are ongoing overhead costs for the distillery, like rent, utilities and staff.

“The rhythm of your cash flow is not going to match the rhythm of your income, and cash flow management is about bridging that gap,” Pearman says.

Cash Flow Forecasting

There are three primary financial reports that make up a business’ financial statements:

- Balance sheet (snapshot of the status of a company at a moment in time)

- Income statement (performance over a period of time)

- Statements of cash flows (sources and uses of cash over a period of time)

Often overlooked is cash flow forecasting, the expected inflow and outflow of cash over future periods.

The cash flow forecast, Pearman notes, is not standard in business financial records. It is usually kept outside of an accounting system as it’s information management generally uses. It’s important because a business can’t rely on just their income statement or bank balance to manage cash flow — labor, overhead and cost of inventory must be part of the expenses. She compared managing cash without a cash flow forecast to “building a house without a hammer.”

“One of the biggest pitfalls that I see with businesses is chasing profitability instead of cash flow,” Pearman says. “It is completely understandable because we’re all hardwired to try to do things as efficiently as we can, get the best deal, but truly in the early stages of a company, it’s way more important to manage cash flow than profitability.”

“It’s a high cost for bringing a new product to market. Cash flow issues are going to be prevalent regardless of where you are in your life cycle, and the best way to guard against cash issues is to have a cash flow forecast.”

During the webinar, Pearman shared a detailed look at a sample business’ financial workbook. She noted that it seems arduous to manage that level of detail but, without it, “you’re really flying blind.”

“It will force you to be highly in tune with the rhythms of your business,” she continues. “It will force you to learn it at such a level that it starts to become innate knowledge, you know it like the back of your hand and there’s no shortcut to that.”

View Pearman’s video presentation, companion presentation and companion spreadsheet.

- Published in Business

Sake Brewers Suffer in Japan

As Covid-19 restrictions are lifted, American sake breweries are opening their doors to customers again. But across the world in Japan, where sake originated, many izakaya or sake pubs remain closed. Japanese brewers expect sales to slump for a second year in a row because of the pandemic.

“This right now might be the most challenging time for the industry,” says Yuichiro Tanaka, president of Rihaku Sake Brewing. “There’s nothing much we can do about that. In our company, we’re trying to become more efficient and streamline our processes so that once the world economy returns to what it formerly was, we’ll be able to much more efficiently fill orders.”

Tanaka, Miho Imada (president and head brewer of Imada Sake Brewing) and Brian Polen (co-founder and president of Brooklyn Kura) spoke in an online panel discussion Brewers Share Their Insider Stories, part of the Japan Society’s annual sake event. John Gauntner, a sake expert and educator, moderated the discussion and translated for Tanaka and Imada, who both gave their remarks in Japanese. (Pictured from left to right: Gautner, Tanaka, Imada and Polen.)

Recovery Struggles

Japan — which has been slow to vaccinate (only 9% of the population has been fully vaccinated, compared to 47% in the United States) — is currently in a third state of emergency. In the country’s large cities, no alcohol can be served in restaurants. “This is just devastating to the industry,” says Gaunter.

Though sake pubs in smaller metropolitan areas and countryside regions are allowed to be open, few people are out drinking. Many pubs have closed, and others refuse entry to anyone from outside of their prefecture.

“Sales of sake are very seriously affected,” says Imada, one of few female tôji or master brewers. “Rice farmers that grow sake rice are seriously affected as well. If brewers can’t sell sake, they have no empty tanks in which to make sake, so they don’t order any rice and the effects are transmitted down to rice farmers.”

Sake rice is more challenging to grow than table rice because the rice grains must be longer. The amount of sake rice planted in Hiroshima — where Imada Sake Brewing is based — is down 30-40%. Farmers may give up growing sake rice and switch to table rice for good.

The effects of Covid-19 on Japan’s sake brewers will linger into the fall when the next brewing season starts again.

“We cannot really expect a recovery in the amount of sake produced next season, and so therefore production will drop for two years in a row,” she says.

Premium sake brewers with rich generational historys — like Imada Sake Brewing and Rihaku Sake Brewing — are struggling to sell their high-end products.. Department store in-store tastings — a boon to premium sake brewers — have disappeared.

Adapting to Covid

In New York, as pandemic recovery efforts continue, Polen has seen the pent-up demand from consumers. Brooklyn Kura’s retail, on-premise and taproom sales are increasing. After scaling back production and their team in 2020, Brooklyn Kura is now hiring again.

“More importantly, and I think the silver lining out of this, we really needed to redouble our efforts to create a direct line of communication with our best customers,” Polen says.

During the pandemic, Brooklyn Kura launched both a direct-to-consumer business and a subscription service featuring limited-run sakes. “That’s helped us on our road to recovery.”

Imada Sake, too, found ways to improve business. They’re selling bottles and hosting tasting events through their website.

“One of the principles of the Hiroshima Tôji Guild [guild of master sake brewers], the expression is ‘Try 100 things and try them 1,000 times.’ Or in other words the point is keep trying new things and see what contributes towards improvement,” Imada says. “These words convey the spirit of using skill and technique or technology to get beyond difficulties.”

Imada Sake exports 20% of its production; as more countries recover, exports continue to grow. Direct-to-consumer sales, she says, vary and are only constant around Christmas.

Rihaku Sake sells much of their sake to distributors and is seeing international exports increase. They also began direct-to-consumer internet sales, but that channel “didn’t grow as much as I was hoping.”

Consumer Education

France and Italy export billions of dollars of wine a year. Polen argues that sake could be an equally profitable export for Japan. Education and exposure, he says, are the challenge.

“In craft beer and fine wine, a lot of those initial encounters with those products come in places like the tap room in Brooklyn or the wineries in California or the local craft brewery, so creating more of those connection points and initial introduction points in a market like the U.S., having a better facility to distribute sake across the U.S., will help to expand the market, not just to domestic producers but also for the storied producers of Japan as well,” Polen says.

Sake is the national beverage of Japan, and strict brewing laws strive to keep it pure. Japanese sake can only be made with koji and steamed rice. Add hops to it and the drink cannot be called sake legally anymore.

Many sake tôji in Japan are running a multi-generational family brewery.“These craftsmen, who have been brewing sake since they were young, have decades of experience to develop what we call keiken to chokkan or experience and intuition,” Tanaka says, adding that Japan is the only place to buy certain industrial-sized sake making machines such as steamers and pressers. “There’s a lot of advantages that breweries in Japan have. If brewers overseas get too good, this might actually cause problems for brewers in Japan. However, more important than that, I think it’s important for all of us to continue to study how to make better and better sake so everyone around the world can enjoy it.”

Rihaku tries to make their sake recognizable to local consumers who are unfamiliar with the rice wine. Their Junmai Ginjo sake has the nickname “Wandering Poet,” a reference to the famous poet Li Po. Legend says Li Po drank a bottle of sake then wrote 1,000 poems.

“We think a lot about how to get more people that are non-Japanese and outside of the Japanese context excited about sake making and excited about the sake we make,” Polen says. “That includes those folks that are passionate fermenters, like the beer community, that really want to know and learn about things like spontaneous fermentation. So (sake) styles, like yamahai and kimoto, are very easy transition points, very easy talking points for us with that community of brewers and consumers that are really excited to drill deeper into fermentation, especially natural fermentation.”

- Published in Business

Fermentation for Alternative Proteins

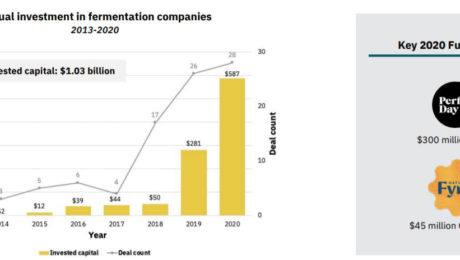

Investments in alternative protein hit their highest level in 2020: $3.1 billion, double the amount invested from 2010-2019. Over $1 billion of that was in fermentation-powered protein alternatives.

It’s a time of huge growth for the industry — the alternative protein market is projected to reach $290 billion by 2035 — but it represents only a tiny segment of the larger meat and dairy industries.

Approximately 350 million metric tons of meat are produced globally every year. For reference, that’s about 1 million Volkswagen Beetles of meat a day. Meat consumption is expected to increase to 500 million metric tons by 2050 — but alternative proteins are expected to account for just 1 million.

“The world has a very large demand for meat and that meat demand is expected to go up,” says Zak Weston, foodservice and supply chain manager for the Good Food Institute (GFI). Weston shared details on fermented alternative proteins during the GFI presentation The State of the Industry: Fermentation for Alternative Proteins. “We think the solution lies in creating alternatives that are competitive with animal-based meat and dairy.”

Why is Alternative Protein Growing?

Animal meat is environmentally inefficient. It requires significant resources, from the amount of agricultural land needed to raise animals, to the fertilizers, pesticides and hormones used for feed, to the carbon emissions from the animals.

Globally, 83% of agricultural land is used to produce animal-based meat, dairy or eggs. Two-thirds of the global supply of protein comes from traditional animal protein.

The caloric conversion ratios — the calories it takes to grow an animal versus the calories that the animal provides when consumed — is extremely unbalanced. It takes 8 calories in to get 1 calorie out of a chicken, 11 calories to get 1 calorie out of a pig and 34 calories to get 1 calorie out of a cow. Alternative protein sources, on the other hand, have an average of a 1:1 calorie conversion. It takes years to grow animals but only hours to grow microbes.

“This is the underlying weakness in the animal protein system that leads to a lot of the negative externalities that we focus on and really need to be solved as part of our protein system,” Weston says. “We have to ameliorate these effects, we have to find ways to mitigate these risks and avoid some of these negative externalities associated with the way in which we currently produce industrialized animal proteins.”

What are Fermented Alternative Proteins?

Alternative proteins are either plant-based and fermented using microbes or cultivated directly from animal cells. Fermented proteins are made using one of three production types: traditional fermentation, biomass fermentation or precision fermentation.

“Fermentation is something familiar to most of us, it’s been used for thousands and thousands of years across a wide variety of cultures for a wide variety of foods,” Weston says, citing foods like cheese, bread, beer, wine and kimchi. “That indeed is one of the benefits for this technology, it’s relatively familiar and well known to a lot of different consumers globally.”

- Traditional fermentation refers to the ancient practice of using microbes in food. To make protein alternatives, this process uses “live microorganisms to modulate and process plant-derived ingredients.” Examples are fermenting soybeans for tempeh or Miyoko’s Creamery using lactic acid bacteria to make cheese.

- Biomass fermentation involves growing naturally occurring, protein-dense, fast-growing organisms. Microorganisms like algae or fungi are often used. For example, Nature’s Fynd and Quorn …mycelium-based steak.

- Precision fermentation uses microbial hosts as “cell factories” to produce specific ingredients. It is a type of biology that allows DNA sequences from a mammal to create alternative proteins. Examples are the heme protein in an Impossible Foods’ burger or the whey protein in Perfect Day’s vegan dairy products.

Despite fermentation’s roots in ancient food processing traditions, using it to create alternative proteins is a relatively new activity. About 80% of the new companies in the fermented alternative protein space have formed since 2015. New startups have focused on precision fermentation (45%) and biomass fermentation (41%). Traditional fermentation accounts for a smaller piece of the category (14%). There were more than 260 investors in the category in 2020 alone.

“It’s really coming onto the radar for a lot of folks in the food and beverage industry and within the alternative protein industry in a very big way, particularly over the past couple of years,” Weston says. “This is an area that the industry is paying attention too. They’re starting to modify working some of its products that have traditionally maybe been focused on dairy animal-based dairy substrates to work with plant protein substrates.”

Can Alternative Protein Help the Food System?

Fermentation has been so appealing, he adds, because “it’s a mature technology that’s been proven at different scales. It’s maybe different microbes or different processes, but there’s a proof of concept that gives us a reason to think that that there’s a lot of hope for this to be a viable technology that makes economic sense.”

GFI predicts more companies will experiment with a hybrid approach to fermented alternative proteins, using different production methods.

Though plant-based is still the more popular alternative protein source, plant-based meat has some barriers that fermentation resolves. Plant-based meat products can be dry, lacking the juiciness of meat; the flavor can be bean-like and leave an unpleasant aftertaste; and the texture can be off, either too compact or too mushy.

Fermented alternative proteins, though, have been more successful at mimicking a meat-like texture and imparting a robust flavor profile. Weston says taste, price, accessibility and convenience all drive consumer behavior — and fermented alternative proteins deliver in these regards.

And, compared to animal meat, alternative proteins are customizable and easily controlled from start to finish. Though the category is still in its early days, Weston sees improvements coming quickly in nutritional profiles, sensory attributes, shelf life, food safety and price points coming quickly.

“What excites us about the category is that we’ve seen a very strong consumer response, in spite of the fact that this is a very novel category for a lot of consumers,” Weston says. “We are fundamentally reassembling meat and dairy products from the ground up.”

- Published in Business, Food & Flavor, Health, Science

Measuring and Monitoring Fermented Food Microbiomes

Analyzing the microbiome of a fermented food will help manage product quality and identify the microbes that make up the microscopic life. Though diagnostic techniques are still developing, they’re getting cheaper and faster.

“Why should we measure the microbial composition of fermented foods? If you can make a great batch of kimchi or make awesome sourdough bread, who cares what microbes are there,” says Ben Wolfe, PhD, associate professor at Tufts University. “But when things go bad, which they do sometimes when you’re making a fermented food, having that microbial knowledge is essential so you can figure out if a microbe is the cause.”

Wolfe and Maria Marco, PhD, professor at University of California, Davis, presented on Measuring and Monitoring Fermented Food Microbiomes during a TFA webinar. Both are members of the TFA Advisory Board. During the joint presentation, the two gave an overview on microbiome analysis techniques, such as culture-dependent and culture-independent approaches.

Measuring Microbial Composition

Wolfe says there are three reasons to measure the microbial composition of fermented foods: baseline knowledge, quality control and labelling details.

“Just telling you what is in that microbial black box that’s in your fermented food that can maybe be really useful for thinking about how you could potentially manipulate that system in the future,” he says.

What can you measure in a fermented food? First there’s structure, which can determine the number of species, abundance of microbes and the different types. And second is function, which can suggest how the food will taste, gauge how quickly it will acidify and help identify known quality issues.

Studying these microorganisms — unseen by the naked eye — is done most successfully through plating in petri dishes. This technique was developed in the late 1800s

“This allowed us to study microorganisms at a single cell level to grow them in the laboratory and to really begin to understand them in depth,” Marco says. “This culture-based method, it remains the gold standard in microbiology today.”

However, there’s been a “plating bias since the development of the petri dish,” she says. Science has focused on only a select few microbes, “giving us a very narrow view of microbial life.” Fewer than 1% of all microbes on earth are known.

The microbes in fermented foods and pathogens have been studied extensively.“Over these 150 years we have now a much better understanding of the processes needed to make fermented foods, not just which microbes are these but what is their metabolism and how does that metabolism change the food to give the specific sensory safety health properties of the final product,” she says

Marco and Wolfe both shared applications of these testing techniques from research at their respective universities.

Application: Olives

At UC Davis, Marco and her colleagues studied fermented olives. Using culture-based methods, they found that the microbial populations in the olives change over time. When the fruits are first submerged for fermentation, there’s a low number of lactic acid bacteria on them — but within 15 days, these microbes bloom to 10-100 million cells per gram.

Marco was called back to the same olive plant in 2008 because of a massive spoilage event. The olives smelled and tasted the same, but had lost their firmness.

Using a culture-independent method to further study what microbes were on the defective olives, she discovered a different microbiota than on normal ones, with more bacteria and yeast.

The culprit was a yeast.“Fermented food spoilage caused by yeast is difficult to prevent,” Marco says. “New approaches are needed.”

Application: Sourdough

At Tufts, Wolfe was one of the leaders on a team of scientists from four different universities that studied 500 sourdough starters with an aim to determine microbial diversity. Starters from four continents were examined in the first sourdough study encompassing a large geographic region.

The research team identified a large diversity among the starters, attributed to acetic acid bacteria. They also found geography doesn’t influence sourdough flavor.

“Everyone talks about how San Francisco sourdough is the best, which it is really great, but in our study we found no evidence that that’s driven by some special community of microbes in San Francisco,” Wolfe said. “You can find the exact same sourdough biodiversity based on our microbiome sequencing in San Francisco that you can find here in Boston or you could find in France or in any part of the world, really.”

Wolfe and Marco will return for another TFA webinar on July 14, Managing Microbiomes to Control Quality.

- Published in Science