Fermented Foods Face Patchwork of Global Regulation & Standards

Should there be global standards for fermented foods? A new study argues “to preserve consumer confidence in fermented foods,” uniform regulations are needed.

Current guidelines “are not mature enough to adequately regulate the significant diversity of fermented foods that are increasingly available in the market,” reads the study, published in the peer-reviewed journal Frontiers in Nutrition. While fermented foods are experiencing a major resurgence in popularity, standards and regulations differ by country and – in some instances – region and state. Fermentation regulations are few and, in the case of some foods, nonexistent.

Scientists at Teagasc, Ireland (the agriculture and food authority in Ireland) studied regulations in North America, South America, Asia, Africa, Europe and Australia/New Zealand. Their research – supported by the Institute for the Advancement of Food and Nutrition Sciences (IAFNS) – is thorough. They found legislative efforts to regulate or standardize fermented foods “have been largely reactive, rather than being proactive, in nature.”

A harmonized blueprint, the study continues, would include specifics for each fermented food, not just the category. Uniform standards would include:

- Microbial and chemical composition

- Safety protocols

- Standards on storage, transportation and distribution

- Communication guidelines

- Regulatory clarity

- Government expert committee oversight

“Ultimately, addressing the challenges outlined here, would contribute to the ease of doing business, encourage consumer and investor confidence, leading to growth and innovation in this category, which in turn will catalyse overall economic progress,” the study reads.

There is also a need for a uniform regulatory framework because there is “…a visible lack of consideration of insights gained from the large corpus of microbiome studies on FFs and their microbial composition in corresponding global Food Standards or Codes.”

There is currently a Codex Alimentarius or “Food Code” by the Codex Alimentarius Commission, part of the Food Standards Programme for the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and the World Health Organization (WHO). But fermented foods are not extensively represented. Regional standards have also been established by FAO and WHO, but these are generally for traditional fermented foods and beverages consumed only in certain regions, not widely used elsewhere.

The study points to South Korea and India as examples. Both countries have consolidated standards and specifications on fermented foods into legislation.

Can the Grocery Industry Adapt?

Three years ago, industry experts predicted a mass retail apocalypse. Consumers were expected to order everything online, abandoning physical stores for websites. The stress of Covid-19 accelerated the trend, shuttering many retailers for good. But one retail category unexpectedly thrived in the pandemic: grocery stores.

“In this environment that should have killed the grocery store in many cases, not only did it not kill it, it strengthened it,” says Ethan Chernofsky, vice president of marketing at Placer.ai, a tech company that tracks and analyzes foot traffic for retailers. “People love grocery shopping and they very often prefer the visit to the store.”

“There’s a love affair with grocery stores,” says Christine LaFave Grace, executive editor of Winsight Grocery Business, a trade publication for the grocery industry..

In the midst of another wave of Covid cases, the war in Ukraine and rising costs due to inflation, “there’s a really continued, sustainable opportunity for the grocery space,” Chernofsky says. Though consumers’ dollar spend at grocery stores has far exceeded industry estimates, the industry needs to adapt to a changing customer.

Chernofsky and Grace shared their views on the marketplace in Winsight’s webinar “2022 Grocery Deep Dive: What’s Changed and Who’s Thriving.”

Regional Shifts

During the pandemic, many consumers – especially young families – left city centers for the suburbs.The suburban grocery shopping experience is new and different for former city dwellers – stores are bigger, selection is greater and the shopper’s pantry space at home is typically much larger.

“A lot of these changes really demand that grocers on a regional and a location-based level to say: ‘What’s changed in our specific area? Where does it provide us with opportunity? Where does it provide us with risks?’” he adds. These are not huge overhauls like moving stores, but minor adapting moves “to better align myself with where the opportunities are.”

For example, coffee shops are one of the strongest performing sectors within the food industry. Grocery stores with on-site coffee bars and an in-house bakery create a similar experience for their shoppers. Selecting merchandise tailored for a local audience also creates a differentiated shopping experience.

“Grocery stores are hitting a whole other level of potential that wasn’t possible a few years ago,” Chernofsky says. “It’s a fundamental shift in what we expect from these areas.”

Recession-Proof

Grocery stores have shown their staying power during economic downturns, since they sell essential products. As America braces for another recession – 68% of CEOs in a recent survey feel one is imminent – buying patterns in groceries are likely to change but not decrease.

“Difficult economic environments [do] not mean everything comes to standstill,” Chernofsky says. People may not have as much money to spend at the grocery store, but they’re still spending.

For example, if restaurant spending drops – as it typically does in a recession – grocery stores can offer consumers the eating-out experience by selling DIY meal kits and grab-and-go meals.

“Everything we’re seeing to this point is showing us demand has been incredibly resilient,” Chernofsky says. “The retailer has to continue to evolve and push to innovate.”

- Published in Business

Marketing Gut Health

Consumers want foods that aid gut health, but brands face a major challenge. How can they educate buyers about microbiome health benefits without getting into trouble with regulators?

“It’s no longer enough to just say ‘healthy,’” says Alon Chen, CEO and co-founder of Tastewise, an “AI platform for food brands.” “We are absolutely more critical of health claims in general. We want to know how, we want to know why and we want it backed by science.”

The term “healthy” is no longer resonating with consumers. Over 30% are looking for products with multifunctional benefits, according to research by Tastewise. They want more detail, on topics such as gut health, sleep improvement, brain function, anti-bloating and energy.

“Food is no longer just about nutrition, nor is it about general health,” says Flora Southey, editor at Food Navigator. “Consumers want more from the food they consume – and they want to be specific about it.”

What are the challenges and opportunities for brands trying to deliver gut health? A panel of food and nutrition experts tackled the issue during a Food Navigator webinar: “From Fermentation to Fortification: How is Industry Supporting Gut Health and Immunity?” Here are highlights.

Regulation Woes

There are trillions of microbes in our gut, but science has only scratched the surface of their power. Gut health is an ambiguous – and often confusing – subject for consumers.

Regulations on gut health claims are evolving. A year ago, the European Food Standard Authority asked food producers to help evaluate microbiome-based product claims.

“In order for us to assert ourselves in the industry, we have to be able to defend and support these claims,” says Anthony Finbow, CEO of Eagle Genomics, a software company incorporating microbiome research into their data analysis.

It’s “the dawn of a new age,” according to Finbow. Major food companies are now valued for delivering nutrition in addition to caloric content. “There is greater consumer understanding that food is a mechanism for better health.”

Southey feels brands need to do more for consumer education “I’m not convinced [the message is] getting to the consumer as well as it should be.”

Nutrition drink brand MOJU is attempting to tackle the regulatory stumbling block of health benefits on a label. Strict rules requiring detailed substantiation have resulted in few gut health claims“We’ve got a long way to go from an education point of view,” says Ross Austen, research and nutrition lead at MOJU.

MOJU can’t use the term “gut health,” but they can say a drink contains vitamin C or D, which have been proven to boost the immune system. They can’t say their drink is anti-inflammatory, but they can say it contains turmeric, known for its anti-inflammatory properties.

Marketing -Biotics

More consumers want the presumed gut health benefits of probiotics, prebiotics and postbiotics to power their microbiome. Probiotics “have largely stolen the headlines over the past few years,” Austen says, but prebiotics are appearing in more and more products. MOJU puts prebiotic fiber in their drinks because probiotics are a challenge for packaged food products. Because probiotics contain live and active cultures, they must be refrigerated and their efficacy tested.

Ashok Dubey, Phd, senior scientist and lead for nutrition sciences at TATA Chemicals (a supplier of chemical ingredients to food and drink producers), agrees. Dubey feels that the benefits of probiotics have been diminished in the minds of consumers. He notes that when probiotics first began appearing in foods 20 years ago, they were claimed to be able to solve any and all health ailments.

“There’s a greater understanding that our gut microbiota is so complex, if the food we eat is so complex, then the solution we should provide should be a combination of all of this,” he says. Dubey is seeing more patents combining probiotics and prebiotics, a complex solution that he says looks at whole health.

But, he notes, any claim with -biotics must be validated by scientific research.

Traditional Foods vs. Clinical Trials

Hannah Crum, president of Kombucha Brewers International (KBI), takes issue with the need to validate every health claim with scientific research. “We shouldn’t displace a huge body of traditional knowledge in favor of pharmaceuticals,” she says.

Making health claims around -biotics has been challenging for the kombucha industry. “It doesn’t honor what food does for us nutritionally,” she adds. Today’s food industry is so heavily regulated that foods traditionally consumed by humans for centuries – like kombucha – can’t put a health claim on a label without proving benefits in a human clincal trial.

“It’s frustrating,” Crum says. ““In fact, because there is no definition of the word probiotic from a legal perspective, it leaves our brands vulnerable to be attacked by parasitic lawyers who just want to extract value from large corporations because they can.”

“In my opinion, we need to honor the fact that all traditionally fermented foods are probiotic by nature instead of saying ‘Well you need the research to prove it,’” she says.

State of Fermentation for Alt Proteins

The world of fermentation-enabled alternative proteins is growing rapidly. Investments in these producers tripled in 2021 to $1.69 billion, and the number of companies increased by 20%.

“It’s really cemented fermentation’s position within alternative proteins and their investment landscape,” says Sharyn Murray, senior investor engagement specialist for the Good Food Institute (GFI). Over $5 billion was invested in alternative proteins last year. “It really demonstrates the central place that alt proteins hold for investors when they consider the future of food.”

Murray and other GFI leaders shared these and other dimensions of the alternative protein space during their annual State of the Industry virtual report. Below are highlights.

Scaling Challenges

Infrastructure is the biggest stumbling block for fermented alternative protein companies.

“The elephant in the room, perhaps the greatest hurdle that alternative protein fermentation effects and the alt protein industry as a whole will face over the next decade, is the looming shortage of available fermentation manufacturing capacity,” says Ryan Dowdy, GFI’s science and technology analysis manager.

Roughly 95% of the existing precision fermentation facilities are outdated and not configured for food production – many were made for pharmaceutical or ethanol production. More precision fermentation capacity was lost in 2021 than added, GFI reports.

Pressing is the need to meet global demand for protein by 2030. That goal, Dowdy notes, will require three times the fermentation capacity that is available today. Companies are building their own facilities – like The Better Meat Co. in Sacramento, Nature’s Fynd in Chicago (pictured Nature’s Fynd CEO Thomas Jonas in their new facility) and Mycorena in Göteborg, Sweden.

Hybrid Products Growing

Alternative food products have typically been categorized in three ways: plant-based, fermented and cultivated. GFI still divides their annual report along those three groupings.

But Audrey Gure, GFI’s startup innovation specialist, says, in the future, “we won’t see alternative protein production platforms as distinct industry segments but really rather one large industry where we produce animal product alternatives across the spectrum utilizing ingredients from one or more technologies to achieve the desired sensory and functional properties. Fermentation will play a critical role in these hybrid products.”

Hybrid examples include alt beef derived from cultivated cow cells that have been grown using fermentation techniques, and plant-based collagen made with fermentation-derived ingredients.

“Fermentation also holds disruptive power for other products made from animals beyond meat, eggs, dairy and seafood,” Gure continues, like “infant nutrition, pet food, honey collagen and gelatin are additional product categories that are seeing fermentation innovations.”

What’s in a Name

Nomenclature and labeling continue to be hotly debated.

“In terms of names used, companies are not completely aligned,” notes Madeline Cohen, GFI’s regulatory attorney.

Though companies have come to a consensus on using the term “animal free,” other descriptors used in the fermented alternative protein spaces are contested. For example, biomass fermentation is called Fermotein by The Protein Brewery and Fy by Nature’s Fynd. Brave Robot, Graeter’s and Starbucks all use Perfect Day’s alternative dairy proteins, but the ice cream producers call it “animal-free dairy” while Starbucks says“animal-free milk.”

In Europe, traditional dairy terms like “milk” and “yogurt” are legally prohibited for use by alternative dairy companies. But the European Parliament in 2020 rejected a similar bill for meat producers. If passed, alt meat companies would not have been able to use traditional meat terms like sausage or burgers for products not derived from an animal carcass. GFI notes several companies in the industry are working together to establish verbiage.

- Published in Business

The “Periodic Table” of Fermented Foods

A pioneering “periodic table” of fermented foods was released this month, the first attempt to represent the breadth and range of fermented foods and beverages in graphic form.

This creation is the brainchild of Michael Gänzle, PhD, professor and Canada Research Chair in Food Microbiology and Probiotics at the University of Alberta. Gänzle is regarded as an expert in fermented foods and lactic acid bacteria. His recent research includes identifying a new taxonomy for the lactobacillus genus, a topic Gänzle spoke about in a TFA webinar.

“Non-traditional fermented foods are a big trend both in industrial food production and in culinary arts,” Gänzle said in an interview with TFA. “The periodic table may be the most concise overview on what is possible if all of the diversity of our benign and beneficial microbial helpers is recruited.”

The impetus for the table dates to 2014, when Gänzle and a colleague used a periodic table of beer styles in their food fermentation class. They wondered if it would be feasible to create a similar version for fermented foods.

Gänzle’s final version, along with his well-documented analysis of the table, was published in the journal Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. The table includes 118 entries of fermented foods, each coded for product category, country of origin, fermentation organism (like LAB, acetic acid bacteria or yeasts), fermentation substrate, metabolites and fermentation time.

Gänzle suggests the table is “quite useful for a number of things that may impact the development of fermented foods.” He says fermentation has “reemerged as a method to provide high-quality food.” A chef or producer can use the table to compare “differences and similarities in the assembly of microbial communities in different fermentations, differences in the global preferences for food fermentation, the link between microbial diversity, fermentation time and product properties, and opportunities of using traditional food fermentations as templates for development of new products.”

Because of its straightforward graphical layout, the table can quickly answer questions. A scan of it shows “which foods contain live fermentation microbes, which regions of the world have which preferences for substrates and fermented foods, which fermented foods are back-slopped and are fermented with host-adapted fermentation organisms.”

He stresses, though, that the table has its limitations, as it doesn’t cover every fermented food.

“The more I read the more likely I am to quote Plato’s rendition of Socrates’ statement that ‘I neither know nor think I know,’” Gänzle says. “Fermented foods are about as diverse as humankind.”

Gänzle plans to continue to revise the table on his personal website. Currently, he and two doctoral students are researching fermented soy and legumes, so look for the next updates to be in those categories.

- Published in Science

The State of Fermentation Education

The Covid-19 lockdown spurred aspiring home chefs around the world to try fermenting for the first time. DIY classes moved virtual and countertops filled with bubbling crocks of kimchi, sauerkraut, kombucha and sourdough. Fermentation was one of the top pandemic hobbies.

For professional fermentation educators, this trend brought new, eager faces to classes. But now, as lockdown restrictions have eased, are people still wanting to experiment making their own microbe-rich food?

We asked three experts to share their thoughts on the current state of fermentation education — author and educator Kirsten Shockey (of The Fermentation School and Ferment Works), writer and educator Soirée-Leone (who can be found via her website) and chef, food scientist and fermentation educator Jori Jayne Emde (of Lady Jayne’s Alchemy and The Fermentation School). [Shockey and Soirée-Leone are both members of TFA’s Advisory Board.]

The question: What is the current state of fermentation education?

Kirsten Shockey, author and educator

Fermentation education is exploding. The time has never been better. The interest in fermentation — both as a topic and in hands-on engagement — keeps gaining momentum. People are both more curious and more confused than I have seen in the past. I think part of that is because with the boom of interest a lot of people are coming forward as experts sharing content without the prerequisites to inform accurately. For example, we see misinformation about the subtle differences in fermentation vs. culturing vs. pickling that end up leaving people who are just dipping their toes in the process a little less unsure. When these folx do engage with true experts they are enthusiastic students who enjoy soaking up all that they can and we see their anxieties dissipate. I speak from the experience of working with solid experts and their students through The Fermentation School. It has been beyond gratifying to work with an amazing group of really talented fermentation educators to grow quality online education and a dedicated “help” community through The Fermentation School. In my other educator hat, as an author, it is less clear to me how that media is working for education, but that is a bigger issue in that the publishing world itself is in a lot of flux.

Soirée-Leone, writer and educator

Folks are connecting with familial, cultural, and traditional roots through fermentation. They are building online communities to share knowledge, taking workshops, participating in residencies, checking books out from libraries, and attending fermentation festivals that are popping up all over the world.

While there is an abundance of information available through books and websites, some folks seek to connect in person through workshops. I find that it’s especially dynamic to teach and learn in collaborative environments to share skills and experiences. There are so many traditions, techniques, and riffs. It is exciting to learn about folks’ travels, study, and experiments — we each have a different fermentation journey and something to teach and learn.

Today is a far cry from when I first started cheesemaking in 1991 with one slim book that sang the praises of junket rennet. Now there are books sharing natural cheesemaking techniques, bloggers happy to answer questions, travelers bringing information home and sharing online, and workshops to attend.

Fermentation is accessible with rudimentary kitchen equipment and improvised incubators and cheese caves. Fermentation is empowering and engaging of all our senses—and learning new things about fermentation is a never-ending journey.

Jori Jayne Emde, chef, food scientist, fermentation educator

My perspective on this is it’s booming! There was a huge burst of interest for online learning during the pandemic, and I have not seen that slow down much. Fermentation is a trendy topic and word with, unfortunately, a tremendous amount of misinformation floating around out there. It’s an important time as an educator to really remain engaged with students, as well as capturing fermentation aspirants, guiding them towards proper and well informed education taught by experts in the field of fermentation and health.

- Published in Food & Flavor

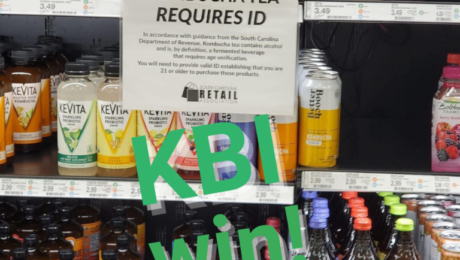

Kombucha Regulations Corrected in South Carolina

A win for kombucha brewers — after a confusing month for those trying to sell their products in South Carolina, they can now sell kombucha as a non-alcoholic beverage in the state.

South Carolina’s Department of Revenue (DOR) had categorized all kombuchas as alcoholic beverages. The state.’s regulations set a maximum alcohol content for beverages but no minimum, so any fermented beverage with any alcohol content would be considered alcoholic. Since kombucha fermentation produces a trace amount of alcohol, a brewer

would need to apply for a state alcohol license, and kombucha could not be sold to anyone under the age of 21.

S.C.’s law contradicts the U.S. legal definition of an alcoholic beverage, which is any product with 0.5% or more alcohol by volume (ABV).

After kombucha industry leaders contacted the state’s DOR and the South Carolina Retail Association (SCRA) to share advice and resources, the regulation was amended to exempt kombucha. Kombucha Brewers International’s leadership and legal counsel, along with producers Buchi Kombucha, GT’s Synergy Kombucha, Health Ade, Humm and Brew Dr., were involved.

“Every time we are called to support commercial producers to advocate on their behalf with government agencies, we validate the category,” said Zane Adams, chair of KBI’s board and co-CEO of Buchi Kombucha and FedUp Foods. “Our very existence means that kombucha is not a fad rather it is a necessary beverage segment that will only continue to grow. We appreciate every opportunity to interface with regulators to help them better understand our product and processes.”

“Crisis creates community,” adds Hannah Crum, KBI president. “Our mission is to advocate and protect kombucha and that’s exactly what we were able to do here thanks to the cooperation of several KBI member and non-member brands. We also appreciate that we were able to create new relationships with the SCRA and the S.C. DOR as we worked together to create a harmonious resolution.”

Most retail stores sell kombucha in the refrigerated juice section. In a press release, KBI shared three points for food regulators who may be unsure in what beverage category kombucha fits:

- Kombucha is not beer. Tax codes that lump kombucha with malt beverages are incorrect.

- Kombucha is an acetic acid ferment. Its fermentation process is similar to that for vinegar. Trace amounts of ethanol will be left in the final ferment, and they act as a natural preservative.

- Hard kombucha is an exception to non-alcoholic kombucha. Hard kombucha is intentionally made with a higher alcohol content, with the purpose to be sold and consumed as an alcoholic beverage.

KBI is currently lobbying for legislation that would exempt kombucha from excise taxes intended for alcoholic beverages. The KOMBUCHA Act, currently in Congress, proposes to raise the ABV threshold for kombucha taxation from its current level of 0.5% to 1.25%. KBI is encouraging the public to sign a petition in support of the act.

While KBI notes it would be ideal to create a new beverage category, “the process is long and arduous and requires a lot of financing for education and lobbying.”

- Published in Business

A Nutrition Pro’s Fermentation Guide

Nutrition professionals need to share the details when recommending fermented products to clients. What are the health benefits of the specific food or beverage ? Does the product contain probiotics? Live microbes?

“There are a vast array of fermented foods. This is important because it means there can be tasty, culturally appropriate options for everyone,” says Hannah Holscher, PhD and registered dietitian (RD). But, she adds, remember that these are complex products.

Holscher spoke at a webinar produced by the International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) and Today’s Dietitian. Joined by Jennifer Burton, RD and licensed dietitian/nutritionist (LDN), the two addressed the topic Fermented Foods and Health — Does Today’s Science Support Yesterday’s Tradition? Hosted by Mary Ellen Sanders, executive director of ISAPP, the presentation touched on the foundational elements of fermented foods, their differences from probiotics, the role of microbes in fermentation, current scientific evidence supporting health claims and how to help clients incorporate fermented foods in their diets.

Sanders called fermented foods “one of today’s hottest food categories.” Today’s Dietitian surveys show they are a top interest to dietitians, as the general public often turns to them with questions about fermented foods and digestive health.

Here are three factors highlighted in the webinar that dietitians should consider before recommending fermented foods and beverages.

Does It Contain Live Microbes?

Fermentation is a metabolic process – microorganisms convert food components into other substances.

In the past decade, scientists have applied genomic sequencing to the microbial communities in fermented foods. They’ve found there’s not just one microbe involved in fermentation, Holscher explained, there may be many. The most common microbes in fermented foods are streptococcus, lactobacillaceae, lactococcus and saccharomyces.

But deciphering which fermented food or beverages contains live microbes can be difficult.

Live microorganisms are present in foods like yogurt, miso, fermented vegetables and many kombuchas. But they are absent in foods that were fermented then heat-treated through baking and pasteurization (like bread, soy sauce, most vinegars and some kombucha). They’re also absent in fermented products that are filtered (most wine and beers) or roasted (coffee and cacao). And there are foods that are mistakenly considered fermented but are not, like chemically-leavened bread, vegetables pickled in vinegar and non-fermented cured meats and fish.

“The main take-home message is that it’s not always easy to tell if a food is a fermented food or not. So you may need to do more digging, either by reading the label more carefully or potentially contacting the food manufacturer,” Holscher said. “When we just think of if live microbes are present or not, a good rule of thumb is if that food is on the shelf at your grocery store, it’s very likely that it does not contain live microbes.”

Does It Contain Probiotics?

The dietitians stressed: probiotics are not the same as fermented foods.

“Probiotics are researched as to the strains and the dosages to be able to connect consumption of a probiotic to a health outcome,” Holscher said. “These strains are taxonomically defined, they’ve been sequenced, we know what these microorganisms can do. They also have to be provided in doses of adequate amounts of the live microbes so foods and supplements are sources of probiotics.”

Though fermented foods can be a source of probiotics, Holscher notes: “In most fermented foods, we don’t know the strain level designation.”

“For most of the microbes in fermented foods, we’ve just really been doing the genomic sequencing of those over the last 10 years and so we may only know them to the genus level right,” she said. For example, we know lactic acid bacteria are present in kimchi and sauerkraut.

Holscher suggests, if a client has a specific health need, a probiotic strain should be recommended based on its evidence-based benefits. For example, the probiotic strain saccharomyces boulardii is known to help prevent travel-related diarrhea, and so would be good for a patient to take before a trip.

“If you’re looking to support health and just in general, fermented foods are a great way to go,” Holscher says.

The speakers recommended looking for probiotic foods in the Functional Food Section of the U.S. Probiotic Guide.

Does Research Support Health Claims?

Fermentation contributes to the functional and nutritional characteristics of foods and beverages. Fermented foods can: inhibit pathogens and food spoilage microbes, improve digestibility, increase vitamins and bioactives in food, remove or reduce toxic substances or anti-nutrients in food and have health benefits.

But research into fermented foods has been minimal, mostly limited to fermented dairy. Dietitians should be careful making strong recommendations based on health claims unless those claims are supported by research. And food labels should always be scrutinized.

“There’s a lot of voices out there that are trying to answer this question [Are fermented foods good for us?],” says Burton. “Many food manufacturers have published health claims on their labels talking about these benefits and, while those claims are regulated, they’re not always enforced. Just because it has a food health claim on it, that claim may not be evidence-based. There’s a lot of anecdotal accounts of benefits coming from eating fermented foods and the research is suggesting some exciting potential mechanisms. But overall we know as dietitians we have an ethical responsibility to practice on the basis of sound evidence and to not make strong recommendations if those are not yet supported by research.”

Reputable health claims are documented in randomized control trials. But only “possible benefits” can be linked to nonrandomized controlled trials. And non-controlled trials are the least conclusive studies of all.

For example, Burton puts miso in the “possible benefits” category because, with its high sodium content, there’s not enough research indicating it’s safe for patients with heart disease. Similarly, she does not recommend kombucha because of its extremely limited clinical research and evidence.

“We have to use caution in making these recommendations,” Burton says.

This is why Burton advises dietitians to be as specific as possible. Don’t just tell patients “eat fermented foods” — list the type of fermented food and its brand name. She also says to give patients the “why” — what is the benefit of this fermented food? Does it increase fiber or boost bioavailability of nutrients?

“Are fermented foods good for us? It’s safe to say yes,” Burton says. “There’s a lot that we don’t know, but the body of evidence suggests that fermentation can improve the beneficial properties of a food.”

Redzepi on the Changing Fine Dining Industry

Expect more changes to fine dining as the restaurant industry grapples with Covid-19 changes, casual eateries adapt more fine dining techniques and the war in Ukraine continues to affect the world economy.

“Everyday restaurants have become so amazing. It’s not like it used to be, you used to go to the best restaurant to get the most tender piece of meat and the perfect ice cream,” says Rene Redzepi. He is the founder of Noma, the Michelin three-star restaurant in Copenhagen lauded as one of the top in the world. “You can find typical luxury ingredients like caviar and wagyu in airports. The quality of cooking now is so high.”

Redzepi spoke at Madrid Fusión, one of the largest and oldest international gastronomy conventions. Andoni Luis Aduriz, chef and owner of the renowned Spanish restaurant Mugaritz, spoke with Redzepi.

Redzepi says there’s been a “flavor spread” or “quality spread” of gastronomy techniques. He points to espumas, the Spanish term for culinary foaming. – now used on every continent, in every level of restaurant. A gourmet dish may come from the neighborhood brasserie, a tapas bar or even a food truck. It’s “dramatically changed” the restaurant industry, he notes.

“That’s because people don’t understand the influence and the philosophies that [are] now completely naturalized in every corner of gastronomy,” he says. Techniques once used only in premier establishments have become part of cooking DNA. “I hope fermentation will be that because I genuinely believe in the power of that.”

When Noma opened in November 2003, Redzepi promised Nordic cuisine made with local produce. But it was winter and freezing, making sourcing food a challenge, “so I stepped into the wilderness to find flavors.”

He also realized Noma needed to conserve summer produce for the long winter.

“We started to use pickling, fermentation, drying, smoking. Twenty years later, we have this bank of knowledge,” he said. “Before, we used to try 20,000 different fermentation techniques, now we are trying one at a time, with the whole team, like we are doing with lacto-fermentation.”

Fermentation drives an enormous amount of innovation at Noma. Redzepi told the Madrid Fusion audience that the restaurant industry is one of the most difficult to work in, so innovation and experience are what drive profitability.

“That’s what makes it special, putting together a team, while constantly looking for the ‘next big thing,’” he says. “That’s where the challenge is; pushing yourself outside of your comfort zone, until you have no clue what you’re doing, but as a group, you draw on your experiences, you trust each other, and you dare to move onwards.”

Redzepi praised the current state of Spain’s cuisine, saying “the Spanish influence is a natural part of any fine dining kitchen in the Western world.”When he was starting out in the 90s, French food was the only focus for chefs. “You were going to cook French food in Denmark, that’s what I always thought to myself.” But when he took a job cooking in Spain for a season, “it was like everything that you had been taught before, all your rules that you knew, were sort of thrown away and you could build and dream in a different way. “[Spanish cuisine] has given me the very seed of everything that’s become Noma.”

- Published in Food & Flavor