The Rise of Fermented Foods and -Biotics

Microbes on our bodies outnumber our human cells. Can we improve our health using microbes?

“(Humans) are minuscule compared to the genetic content of our microbiomes,” says Maria Marco, PhD, professor of food science at the University of California, Davis (and a TFA Advisory Board Member). “We now have a much better handle that microbes are good for us.”

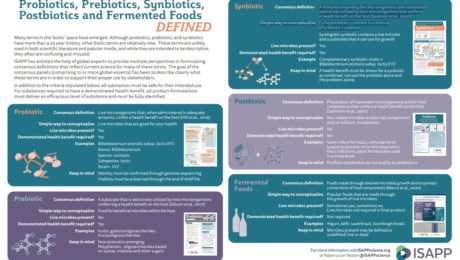

Marco was a featured speaker at an Institute for the Advancement of Food and Nutrition Sciences (IAFNS) webinar, “What’s What?! Probiotics, Postbiotics, Prebiotics, Synbiotics and Fermented Foods.” Also speaking was Karen Scott, PhD, professor at University of Aberdeen, Scotland, and co-director of the university’s Centre for Bacteria in Health and Disease.

While probiotic-containing foods and supplements have been around for decades – or, in the case of fermented foods, tens of thousands of years – they have become more common recently . But “as the terms relevant to this space proliferate, so does confusion,” states IAFNS.

Using definitions created by the International Scientific Association for Postbiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP), Marco and Scott presented the attributes of fermented foods, probiotics, prebiotics, synbiotics and postbiotics.

The majority of microbes in the human body are in the digestive tract, Marco notes: “We have frankly very few ways we can direct them towards what we need for sustaining our health and well being.” Humans can’t control age or genetics and have little impact over environmental factors.

What we can control, though, are the kinds of foods, beverages and supplements we consume.

Fermented Foods

It’s estimated that one third of the human diet globally is made up of fermented foods. But this is a diverse category that shares one common element: “Fermented foods are made by microbes,” Marco adds. “You can’t have a fermented food without a microbe.”

This distinction separates true fermented foods from those that look fermented but don’t have microbes involved. Quick pickles or cucumbers soaked in a vinegar brine, for example, are not fermented. And there are fermented foods that originally contained live microbes, but where those microbes are killed during production — in sourdough bread, shelf-stable pickles and veggies, sausage, soy sauce, vinegar, wine, most beers, coffee and chocolate. Fermented foods that contain live, viable microbes include yogurt, kefir, most cheeses, natto, tempeh, kimchi, dry fermented sausages, most kombuchas and some beers.

“There’s confusion among scientists and the public about what is a fermented food,” Marco says.

Fermented foods provide health benefits by transforming food ingredients, synthesizing nutrients and providing live microbes.There is some evidence they aid digestive health (kefir, sourdough), improve mood and behavior (wine, beer, coffee), reduce inflammatory bowel syndrome (sauerkraut, sourdough), aid weight loss and fight obesity (yogurt, kimchi), and enhance immunity (kimchi, yogurt), bone health (yogurt, kefir, natto) and the cardiovascular system (yogurt, cheese, coffee, wine, beer, vinegar). But there are only a few studies on humans that have examined these topics. More studies of fermented foods are needed to document and prove these benefits.

Probiotics

Probiotics, on the other hand, have clinical evidence documenting their health benefits. “We know probiotics improve human health,” Marco says.

The concept of probiotics dates back to the early 20th century, but the word “probiotic” has now become a household term. Most scientific studies involving probiotics look at their benefit to the digestive tract, but new research is examining their impact on the respiratory system and in aiding vaginal health.

Probiotics are different from fermented foods because they are defined at the strain level and their genomic sequence is known, Marco adds. Probiotics should be alive at the time of consumption in order to provide a health benefit.

Postbiotics

Postbiotics are dead microorganisms. It is a relatively new term — also referred to as parabiotics, non-viable probiotics, heat-killed probiotics and tyndallized probiotics — and there’s emerging research around the health benefits of consuming these inanimate cells.

“I think we’ll be seeing a lot more attention to this concept as we begin to understand how probiotics work and gut microbiomes work and the specific compounds needed to modulate our health,” according to Marco.

Prebiotics

Prebiotics are, according to ISAPP, “A substrate selectively utilized by host microorganisms conferring a health benefit on the host.”

“It basically means a food source for microorganisms that live in or on a source,” Scott says. “But any candidate for a prebiotic must confer a health benefit.”

Prebiotics are not processed in the small intestine. They reach the large intestine undigested, where they serve as nutrients for beneficial microorganisms in our gut microbiome.

Synbiotics

Synbiotics are mixtures of probiotics and prebiotics and stimulate a host’s resident bacteria. They are composed of live microorganisms and substrates that demonstrate a health benefit when combined.

Scott notes that, in human trials with probiotics, none of the currently recognized probiotic species (like lactobacilli and bifidobacteria) appear in fecal samples existing probiotics.

“There must be something missing in what we’re doing in this field,” she says. “We need new probiotics. I’m not saying existing probiotics don’t work or we shouldn’t use them. But I think that now that we have the potential to develop new probiotics, they might be even better than what we have now.”

She sees great potential in this new class of -biotics.

Both Scott and Marco encouraged nutritionists to work with clients on first improving their diets before adding supplements. The -biotics stimulate what’s in the gut, so a diverse diet is the best starting point.

Natural & Health Labels Can be Regulatory Nightmare

Brands need to be extra vigilant over the health claims they put on their labels. A simple phrase like “Supports immunity,” “Aids respiratory health” or “Full of natural flavors” could result in a lawsuit from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), Federal Trade Commission (FTC) or a state attorney general.

“The FDA is able to set very broad and very narrow regulations in terms of what our labels can look like, what can be included in the products, what kind of claims we can make for the products, who the products can be distributed too, how they can be imported and exported and the like,” says Claudia Lewis, partner at Venable LLP, a Washington D.C.-based law firm.

Complying with these sometimes archaic laws can be challenging. The FDA, which ensures food safety, has a large jurisdictional footprint, regulating about 30 cents of every dollar Americans spend. The FTC is the authority on advertising and marketing claims for food, beverage and supplement products, and it may challenge a food brand if its marketing is deemed false, deceptive and/or misleading.

“Typically, if you’re in an FTC investigation, you’re going to have at least $300,000 in legal fees by the time you’re finished, if not over half a million dollars,” says Todd Harrison, partner at Venable. “The FTC is a very expensive regulatory agency to deal with. They can make your life pretty miserable.”

Harrison and Lewis specialize in representing functional food brands at their law firm and spoke at Expo East on the topic of Legal and Regulatory State of the Natural Products Industry. [The Fermentation Association’s virtual conference, FERMENTATION 2021 will also cover this and related topics — please check our Agenda for the latest sessions and speakers.]

Harrison and Lewis reviewed two main areas where improper labeling can get a food brand into trouble with regulators.

Using Covid-19 as a Marketing Tool

Shortly after the Covid-19 pandemic started, the FDA offered a unique relaxation of their rules and regulations for food products. Brands were challenged with supply chain disruptions and ingredient shortages. The FDA allowed temporary ingredient and formulation changes without a label overhaul, as long as the new ingredient was non-allergenic, 2% or less of the weight of the finished product, not a main or characterizing ingredient and not affecting health claims.

Though the temporary rule allows for flexibility, Harrison advises it still leaves room for litigation. Plaintiff attorneys can still sue for changes in a product’s flavor.

“Minor changes are fine from an FDA perspective, but not necessarily good from a plaintiff perspective,” he adds.

Covid-19 has also spurred a gray area in food marketing claims. Labels claiming the product prevents, treats or mitigates Covid-19 are illegal and being “aggressively pursued.”

“Anytime you mention the word coronavirus or Covid, the FDA is not going to agree with what you say because everyone will think you’re somehow implying something,” Harrison says.

Context is critical, as the agency is cracking down on any brands making health claims implying their product could prevent Covid. Brands using the phrases “immunity support” or “immune boosting” on their labels — or even on their social media pages — could be targeted by the FDA.

“The FDA has historically not liked (brands to use the term) immunity, but it was always low risk (pre-pandemic), you’d likely get a warning letter,” Harrison says. “However, in the world we live in today, the word immunity is persona non grata to the agency. Especially if you add the word respiratory on it. If you put the words ‘immunity’ and ‘respiratory’ on a label, the agency is saying ‘It’s Covid.’”

Harrison also cautions against connecting science-backed supplements and vitamins to treating a Covid infection. He uses the example of vitamin D — plentiful scientific research proves vitamin D boosts immunity, but a food brand cannot legally make that association, and doing so can set it up for litigation. Though vitamin D “is a cheap way of helping reduce your risk of (Covid-19) severity, it’s not going to keep you from getting Covid,” Harrison explains. “The way the paradigm is set up, even if you have really good science in your favor, you can’t make the claim unless you have approval by the FDA.”

“Natural” and “Health Food” Still Debatable Terms

Because there is no FDA or FTC definition of “natural,” lawsuits against brands claiming their product is natural or similar claims are prevalent. (The FDA requested public comments on the term “natural” in 2016, but no rule was issued on the policy.)

And these lawsuits don’t always come from the federal agencies. Class action lawsuits are “still alive and well,” Lewis adds. A formal definition would help protect brands because plaintiffs are filling in the holes and filing costly lawsuits. She uses the example of Welch’s Fruit Snacks, which was sued for being “more candy than fruit.”

“The plaintiffs bar has seized on that and taken these companies to task,” she says. “This wording about ‘healthy’ and this wording of ‘natural’ is also taking on a different dynamic because of consumer perception. How consumers perceive these words and how consumers’ expectations are not keeping with FDA regulations, but the plaintiff bar is using that as an opening and getting pretty good settlements in connection with consumer perception.”

Making a health inference is a slippery slope. The FDA deems a healthy food as one that suggests the product can help maintain “healthy dietary practices.” Health foods are required to be low in fat, saturated fat, cholesterol and sodium.One or more qualifying nutrients must also make up at least 10% of their weight..

For example, IZZE, makers of sparkling juices, was sued for misleading marketing because, though the drink advertised “no sugar added,” it failed to disclose it was not low in calories — a requirement under FDA regulations. Harrison takes issue with the FDA defining healthy in these confusing terms.

“I’d say it’s unconstitutional and I think I’d win that case because healthy is now low fat, low saturated food and a certain amount of macronutrients. It’s a much more complex question than that. But yet this is what plaintiff attorneys seize on,” Harrison says.

Though a new food product may be utilizing health ingredients on the cutting edge of scientific research, Harrison warns the FDA is “notoriously behind nutrition science” and brands need to be careful. He says don’t trust the government agency to keep up.

“Nutrition has evolved and continues to evolve,” he says, noting the FDA regulation to put “low fat” as a nutrient content claim just stripped fat out of food (including beneficial fat) and replaced it with simple carbohydrates. Most members of Congress “don’t know a damn thing” about health food. “We know what’s good for us. We’re not stupid people.”

Natural & Organic Sales Growing but Slowing

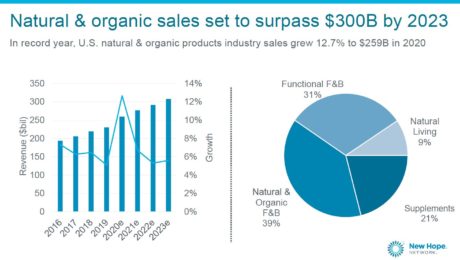

Sales of natural and organic products grew nearly 13% to $259 billion in 2020 , “despite the pandemic and, in some ways, because of the pandemic.”

“It’s very strong and, in many ways, it’s never been stronger,” says Carlotta Mast, senior vice president of the New Hope Network (producers of the event). Between pandemic-driven pantry loading, new brand exploration and the drive to purchase healthier, natural products, “people tried those new brands and, in many cases, they stuck with them, especially across the food and beverage categories.”

Mast shared these stats during the State of the Natural & Organic presentation at Natural Products Expo East. But forecasts show sales growing at a slower pace this year, to $271 billion. By 2023, sales are projected to surpass $300 billion.

Natural foods and beverages (including most fermented products) account for 70% of all natural product sales (the rest includes items like supplements and home and pet care products). Natural products are growing three times as fast as their mainstream counterparts.

“Not only were we growing quickly, we were outpacing the rest of the store…not only did our sales accelerate, they drove the whole (food) industry forward,” says Kathryn Peters, executive vice president at SPINS (a data provider for natural, organic and specialty products). “We’re finding consumers are coming and staying and continuing to buy more.”

Expo East Returns In-Person

Expo East is the first major food trade show to meet in-person since the Covid-19 pandemic shuttered events in March 2020. New Hope Network used a hybrid virtual and in-person model to produce the show, live-streaming the conference portion to virtual attendees.

“It was really exciting and satisfying to be back on a live show floor, interacting with people again. There was a real buzz,” says Chris Nemchek, TFA’s buyer relations director. “On day 1, you could tell there was a lot of pent-up demand.”

Health precautions were increased. Attendees had to show a Covid-19 vaccination card or a negative Covid-19 test administered within 72 hours. Masks were mandatory. Badges were no longer distributed to all attendees, only being printed upon request.

Food sampling, too, was much different than at a typical pre-pandemic trade show. Samples were only given by a gloved brand representative at an exhibitor’s booth. Food was stored behind sneeze guards, and surfaces were wiped down frequently.

“Exhibitors gave away less product, but the product they did give away was for more productive reasons — the people who took the sample really wanted it,” Nemchek notes.

“It was a good step back towards normal, but it wasn’t normal,” he adds. The size of the crowd at the show was not close to pre-pandemic levels (attendance numbers have not been released). But Nemchek notes that New Hope should still be pleased. “There’s now more confidence in the industry in putting on a food show again.”

Immune Health Driving Purchases

The natural and organic industry’s most popular products continue to be ones supporting immunity, health and wellness. Those attributes were consumer’s top purchase priorities in 2020, and remain strong in 2021.

Paleo (+25%), grain-free (+17%) and plant-based (+13%) foods and beverages registered the strongest sales growth. Plant-based products have seen especially strong sales over the past two years.

“Covid was a major driver for this boost in sales growth,” Mast says. Now “it’s our opportunity to keep those consumers.”

Consumers are exploring how they can use their diet as the first line of defense against illness, Peters adds. Immunity-related ingredients traditionally found on the supplement aisle, like cider vinegar, collagen, elderberry, moringa and ashwagandha,are now in grocery and refrigerated products.

“It’s revolutionizing the aisles in the store,” Peters says.

Changing Grocery Store Shelves

The U.S. is diversifying faster than predicted as well, and those demographic changes are influencing what’s selling. International foods are outperforming in grocery sales, growing at a 21% rate (compared with U.S. food at 16%).

“This is a huge shift for our country,” Mast says. “We’re seeing that, across our industry, more consumers are looking for that multicultural food.”

Mast notes, though, that leadership of the natural and organic products industry does not reflect the U.S. population.More BIPOC representation is needed on i company boards and leadership teams.

Shopping with Values

Consumers’ social and environmental values are also driving purchasing behavior. A survey by Nutrition Business Journal and SPINS found 76% of natural shoppers pay more for high-quality ingredients, 57% avoid buying food grown on industrial feedlots or chemical-intensive farms and 53% will pay more to support businesses that are socially- or environmentally-responsible. Consumers want companies to take social and political stances that reflect their own values.

“Our industry, because of our size, our scale and our influence, we could truly help create solutions to these problems and be part of building that new future,” Mast adds. “Think about the changes that we could help create for people, animal, planet — but it’s if we chose to do so.”

- Published in Business, Food & Flavor

Supplements vs. Fermented Foods

Two UCLA professors of medicine encourage people “rather than thinking in terms of supplements, add some fermented foods to your diet.” In a Q&A, the doctors say the popularity of probiotics, postbiotics and the gut microbiome has blurred their value, despite the plethora of reputable scientific research. Product manufacturers — as has happened before, with terms like “gluten-free” — have begun labelling everything as containing -biotics or benefitting the gut microbiome.

“The word probiotics refers to the beneficial microbes found in certain fermented foods and beverages, as well [as] in specially formulated nutritional supplements,” write UCLA doctors Eve Glazier and Elizabeth Ko. “That means that any fermented food that contains or was made by live bacteria contains postbiotics. … Initial findings suggest that postbiotics may play a role in maintaining a balanced and robust immune system, support digestive health and help to manage the health of the gut microbiome.”

Read more (Journal Review)

- Published in Science

What’s the Actual Probiotic Count of Commercial Kefir?

A new peer-reviewed study from researchers at the University of Illinois and Ohio State University found 66% of commercial kefir products overstated probiotic count and “contained species not included on the label.”

Kefir, widely consumed in Europe and the Middle East, is growing in popularity in the U.S. Researchers examined the bacterial content of five kefir brands. Their results, published in the Journal of Dairy Science, challenge the “probiotic punch” the labels claim.

“Our study shows better quality control of kefir products is required to demonstrate and understand their potential health benefits,” says Kelly Swanson, professor in human nutrition in the Department of Animal Sciences and the Division of Nutritional Sciences at the University of Illinois. “It is important for consumers to know the accurate contents of the fermented foods they consume.”

Probiotics in fermented products are listed in colony-forming units (CFUs). The more probiotics, the greater the health benefit.

According to a news release from the University of Illinois: “Most companies guarantee minimum counts of at least a billion bacteria per gram, with many claiming up to 10 or 100 billion. Because food-fermenting microorganisms have a long history of use, are non-pathogenic, and do not produce harmful substances, they are considered ‘Generally Recognized As Safe’ (GRAS) by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and require no further approvals for use. That means companies are free to make claims about bacteria count with little regulation or oversight.”

To perform the study, the researchers bought two bottles of each of five major kefir brands. Bottles were brought to the lab where bacterial cells were counted and bacterial species identified. Only one of the brands studied had the amount of probiotics listed on its label.

“Just like probiotics, the health benefits of kefirs and other fermented foods will largely be dependent on the type and density of microorganisms present,” Swanson says. “With trillions of bacteria already inhabiting the gut, billions are usually necessary for health promotion. These product shortcomings in regard to bacterial counts will most certainly reduce their likelihood of providing benefits.”

The news release continues:

When the research team compared the bacteria in their samples against the ones listed on the label, there were distinct discrepancies. Some species were missing altogether, while others were present but unlisted. All five products contained, but didn’t list, Streptococcus salivarius. And four out of five contained Lactobacillus paracasei.

Both species are common starter strains in the production of yogurts and other fermented foods. Because those bacteria are relatively safe and may contribute to the health benefits of fermented foods, Swanson says it’s not clear why they aren’t listed on the labels.

Although the study only tested five products, Swanson suggests the results are emblematic of a larger issue in the fermented foods market.

“Even though fermented foods and beverages have been important components of the human food supply for thousands of years, few well-designed studies on their composition and health benefits have been conducted outside of yogurt. Our results underscore just how important it is to study these products,” he says. “And given the absence of regulatory scrutiny, consumers should be wary and demand better-quality commercial fermented foods.”

The New Definition of Fermented Food

After Dr. Bob Hutkins finished a presentation on fermented foods during a respected nutrition conference, the first audience question was from someone with a PhD in nutrition: “What are fermented foods?”

“I thought ‘Doesn’t everyone know what fermentation is?’ I realized, we do need a definition. Those of us that work in this field know what we’re talking about when we say fermented foods, but even people trained in foods do not understand this concept,” says Hutkins, a professor of food science at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. He presented The New Definition of Fermented Foods during a webinar with TFA.

Hutkins was part of a 13-member interdisciplinary panel of scientists that released a consensus definition on fermented foods. Their research, published this month in Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology, defines fermented foods as: “foods made through desired microbial growth and enzymatic conversions of food components.”

“We needed a definition that conveyed this simple message of a raw food turning into a fermented food via microorganisms,” Hutkins says. “It brings some clarity to many of these issues that, frankly, people are confused about.”

David Ehreth, president and founder of Alexander Valley Gourmet, parent company of Sonoma Brinery (and a TFA Advisory Board member), agreed that an expert definition was necessary.

“As a producer, and having started this effort to put live culture products on the standard grocery shelf, I started doing it as a result of unique flavors that I could achieve through fermentation that weren’t present in acidified products,” Ehreth says. “Since many of us put this on our labels, we should be paying close attention to what these folks are doing, since they are the scientific backbone of our industry.”

Hutkins calls fermented foods “the original shelf-stable foods.” They’ve been used by humankind for over thousands of years, but have mushroomed in popularity in the last 15. Fermented foods check many boxes for hot food trends: artisanal, local, organic, natural, healthy, flavorful, sustainable, innovative, hip, funky, chic, cool and Instagram-worthy.

Nutrition, Hutkins hypothesizes, is a big driver of the public’s interest in fermentation. He noted that Today’s Dietitian has voted fermented foods a top superfood for the past four years.

Evidence to make bold claims about the health benefits of fermentation, though, is lacking. Hutkins says there is observational and epidemiological evidence. But randomized, human clinical trials — “the highest evidence one can rely on” — are few and small-scale for fermented foods.

Hutkins shared some research results. One study found that Korean elders who regularly consume kimchi harbor lactic acid bacteria (LAB) in their GI tract, providing compelling evidence that LAB survives digestion and reaches the gut. Another study of cultured dairy products, cheese, fermented vegetables, Asian fermented products and fermented drinks found that most contain over 10 million LAB per gram.

Still, the lack of credible studies is “a barrier we have to get past,” Hutkins says. There are confirmed health benefits with yogurt and kefir, but this research was funded by the dairy industry, a large trade group with significant resources.

“I think there’s enough evidence — most of it through these associated studies — to warrant this statement: fermented foods, including those that contain live microorganisms, should be included as part of a healthy diet.”

Are Fermented Foods Probiotics?

Probiotics and fermented foods are not equivalent, says Mary Ellen Sanders, PhD and executive science officer of the International Scientific Association of Probiotics & Prebiotics (ISAPP). She advises fermented food producers that don’t meet the criteria of a probiotic to use descriptors such as “live active cultures” or “fermented food with live microbes” on their labels rather than “probiotic.”

“There are quite a few differences between probiotics and many fermented foods. You cannot assume a fermented food is a probiotic food even if it has live cultures present,” says Sanders. She highlighted her 30 years worth of insight into the field during a TFA webinar, Are Fermented Foods Probiotics?

Some fermented foods do meet these criteria, such as some yogurts and cultured milks that are well-studied. But many traditional fermented foods do not.

Using multiple peer-reviewed scientific studies and conclusion from expert panels in the fields of probiotics and fermented foods, Sanders shared the ways in which fermented foods and probiotics differ:

- Health benefits

By definition, a probiotic must have a documented health benefit. Many fermented foods have not been tested for a health benefit.

“If you are interested in recommending health benefits from a fermented food in an evidence-based manner, many traditional fermented foods fall short. They don’t have the controlled randomized trials that will provide a causal link between the food and the health benefit,” she says. “A food may be nutritious, but probiotic benefits must stem from the live microbe, not the nutritional composition of the food. Otherwise you just have a nutritious food that happens to have live microorganisms in it. You don’t have a probiotic food.”

- Quality studies

In her presentation, Sanders shared multiple randomized clinical trials on human subjects with supported health evidence for probiotics. But there are few randomized, controlled studies on fermented foods. Most are cohort studies, which inherently have a higher risk of bias and cannot provide a causal link between consuming fermented foods and a health benefit.

“A strong hypothesis is not the same as proof,” Sanders says. “Evidence for probiotics must meet a higher standard than small associative studies, many of which are tracking biomarkers and not health endpoints.”

She noted, though, there are some studies on fermented milk and yogurt that show a conferred health benefit.

- Strain designation

Though many fermented foods do have live microbes, a probiotic is required to be identified to the strain level. The genus and species should also be properly named according to current nomenclature. Many fermented foods contain undefined microbial composition. Without that strain designation, one can’t tie the scientific evidence on that strain to the probiotic product.

- Microbe quantity

Another key differentiator is that probiotics must be delivered at a known quantity that matches the amount that results in a health benefit. Probiotics are typically quantified in colony forming units (or CFUs).

“A probiotic has a known effective dose. But fermented foods often contain unknown levels of microbes, especially at time of consumption,” Sanders says.

What Can Brands Do?

If food brands keep using the word probiotics as a catch-all to describe a fermented product, the term will lose its utility. Using “probiotics” on food with unsubstantiated proof of probiotics is a misuse of the term.

“When I see a fermented food that says probiotics on it, I very often think what they’re trying to communicate on that label [is that it] contains live microbes,” Sanders says, “because I’m doubting, at least some of the products I see, that they have any evidence of a health benefit. And so they’re just looking for a catchy, single word that will communicate to people that this has live microbes in it. ‘Live active cultures’ is something that resonates with people as well. So why not use that?”

Sanders encourages fermented brands to standardize the terms “live active cultures,” “live microbes,” “live microorganisms” or “fermented food with live microbes.” For products pasteurized after fermentation, there’s a term for them too: “Made with live cultures.”

Controlled human studies on fermented foods can be challenging, Sanders admits. Such studies can be difficult to properly blind, since placebos for foods are hard to design. The fermentation process affects the product taste so that study subjects may know what they are consuming. But the health benefits of fermented foods could be studied, though. She also advises producers to focus on the nutritional value of their food.

“That’s one thing that really has me excited about this concept of core benefits,” says Maria Marco, PhD, professor of food science and technology at University of California, Davis (and a member of TFA’s Advisory Board) and moderator of the webinar. “I think it kind of opens the doors to the possibility of fermented fruits and vegetables where there’s certain organisms, microorganisms that we’d expect to be there but again we need to know really if those microorganisms are needed to make those foods healthy.”

New FDA Requirements for Fermented Food

By August, any manufacturer labeling their fermented or hydrolyzed foods or ingredients “gluten-free” must prove that they contain no gluten, have never been through a process to remove gluten, all gluten cross-contact has been eliminated and there are measures in place to prevent gluten contamination in production.

The FDA list includes these foods: cheese, yogurt, vinegar, sauerkraut, pickles, green olives, beers, wine and hydrolyzed plant proteins. This category would also include food derived from fermented or hydrolyzed ingredients, such as chocolate made from fermented cocoa beans or a snack using olives.

Read more (JD Supra Legal News)

Food and Beverage Laws Passed in 2020

Every year, the nation’s 50 state legislatures pass dozens of new laws that have an impact on fermenters. For example, some states amended alcohol laws to allow drink sampling for craft wineries, while others repealed outdated cottage food laws to help small producers operate and more loosened take-out restrictions to help small restaurants survive the pandemic.

Indicative of this year’s focus on the pandemic, laws were introduced but never debated as lawmakers focused on more pressing issues surrounding the coronavirus. The most common new laws passed in 2020 revolved around helping businesses survive — states called special sessions to aid restaurants, stop price gouging of high-demand products and provide emergency grants to small businesses.

Read on for key food, beverage and food service laws passed this year, most taking effect in 2021.

California

AB82 — Prohibits an establishment with an alcohol license from employing an alcohol server without a valid alcohol server certification.

AB3139 — Establishments with alcoholic beverages licenses who had premises destroyed by fire or “any act of God or other force beyond the control of the licensee” can still carry on business at a location within 1,000 feet of the destroyed premise for up to 180 days.

Delaware

HB 237 — Eliminates old requirements that movie theaters selling alcohol must have video cameras in each theater, and that an employee must pass through each theater during a movie showing.

HB275 — Permits beer gardens to allow leashed dogs on licensed outdoor patios.

HB349 — Permits any restaurant, brewpub, tavern or taproom with a valid on-premise license to sell alcoholic beverages for take-out or drive through food service, so long as the cost for the alcohol did not exceed 40% of the establishment’s total sales transactions.

Hawaii

SR84 — Creates a Restaurant Reopening Task Force to help restaurants in Hawaii safely reopen that were closed during the COVID-19 pandemic.

SR94 — Urges restaurants to adopt recommended best practices and safety guidelines developed by the United States Food and Drug Administration and National Restaurant Association in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Idaho

HB343 — Amends existing law to require licensing to store and handle wine as a wine warehouse.

HB575 — Allows sampling of alcohol products at liquor stores, which was formerly forbidden under law.

SB1223 — Eliminates obsolete restrictions on food products, to match federal standards. It repeals requiring extra labels on some imported food products, and repeals using enriched flour in bread baking.

Illinois

HB2682 — Amends Liquor Control Act of 1934. Allows a cocktail or mixed drink placed in a sealed container at the retail location to be sold for off-premises consumption if specified requirements are met. Prohibits third-party delivery services from delivering cocktails or mixed drinks.

HB4623 — Amends Food Handling Regulation Enforcement Act, regulating that public health departments provide a certificate for cottage food operations, which must be displayed at all events where the licensee’s food is being sold.

Iowa

HB2238 — Amends code regarding food stands operated by a minor. Bans a municipality from enforcing a license permit or fee for a minor under the age of 18 to sell or distribute food at a food stand.

Kentucky

HB420 — Implements Food Safety Modernization Act, authorizing a department representative to enter a covered farm or farm eligible for inspection.

SB99 — Amends alcohol laws for state’s distillers, brewers and small wineries. Eliminates the sunset on local precinct elections to grant distilleries, and allows distillers to sell other distiller’s products.

Louisiana

HR17 — Allows third-party delivery services to deliver alcohol.

HB136 — Makes adulterating a food product by intentional contamination a crime.

SB455 — Increases the size of containers of high-alcoholic beverages.

SB508 — Gives restaurants protection from lawsuits involving COVID-19. The public will be unable to sue restaurants for COVID-19-related deaths or injuries, as long as the restaurant complies with state, federal and local regulations about the virus.

Maine

LD1167 — Encourages state institutions to serve Maine food and Maine food products, increasing the visibility of the state’s local food producers.

LD1884 — Amends current laws regarding businesses that hold dual liquor licenses, which authorized retailers to sell wine for consumption both on- and off-premise. Retailers with the dual license can now sell with just one employee at least 21 years of age present, and adds that wine can be sold for take-out if food is part of the transaction.

Maryland

HB1017 — Allows cottage food businesses to put their phone number and business ID on their food label, rather than their address as currently required by the Maryland Department of Health.

SB118 — Expands definition of “alcohol production” and “agricultural alcohol production.” The new definitions aim to give Maryland farmers and producers the ability to sell beer, wine and spirits to increase agritourism.

Massachusetts

SB2812 — Expands alcohol take-out and delivery options during COVID-19 pandemic. Allows restaurants to sell mixed drinks in sealed containers alongside other take-out and delivery food orders.

Michigan

HB5343 — Revises regulations on brewpubs and microbreweries, increasing the quantity of beer a microbrewer is permitted to deliver to a retailer during a year from 1,000 barrels to 2,000 barrels.

HB5345 — Amends the Michigan Liquor Control Code to delete the Michigan Liquor Control Commission (MLCC) $6.30 tax levied on each barrel of beer manufactured and sold in Michigan.

HB5354 — Amends the Michigan Liquor Control Code to delete the requirement that a brewpub cannot sell beer in Michigan unless it provides for each brand or type of beer sold a label that truthfully describes the content of each container.

SB711 — Establishes new limited production brewer license for microbreweries at cost of $1,000 for license.

HB5356 — Amends the Michigan Liquor Control Code to ban the required $13.50 cent-per-liter tax on all wine containing 16% or less of alcohol by volume sold in Michigan.

Minnesota

HB5 — Authorizes emergency, small-business grants and loan funding for businesses affected by COVID-19.

HB4599 — Extends period of mediation for Minnesota farmers suffering economic difficulties to keep their farm.

Mississippi

HB326 — Amends outdated code to increase the maximum annual gross sales for a cottage food operation (from $20,000 to $35,000) before the producer would need to pay food establishment permit fees. Authorizes a cottage food operation to advertise products over the internet.

New Jersey

AB2371 — Requires large generators of food waste (like restaurants and supermarkets) to recycle food garbage rather than send it to incinerators or landfills.

AB3865 — Limits return of food from retail food stores during a public emergency.

SB864 — Prohibits sale of single-use plastic carryout bags, single-use paper carryout bags and polystyrene foam food service products, and limits single-use plastic straws.

SB1591 — Allows alcoholic beverages to be consumed from open containers in the Atlantic City Tourism District.

SB2437 — Limits service fees charged to restaurants by third-party food takeout and delivery applications during COVID-19 pandemic.

New Mexico

SB3 — Enacts the Small Business Recovery Act of 2020, which provides loans for small businesses suffering during the coronavirus pandemic.

New York

SB8225 — Authorizes issuing a retail license for on-premise consumption of food and beverage within 200 feet of a church, synagogue or other place of worship.

AB8956 — Allows a licensed brewery or farm brewery to provide no more than four beer samples not exceeding four fluid ounces each.

SB1472 — Requires hospitals to offer plant-based food options to patients upon request.

SB7013 — Authorizes the manufacture and sale of ice cream or other frozen desserts made with liquor.

North Carolina

SB290 — The Alcoholic Beverage Control Regulatory Reform Bills, it allows distilleries the same serving privileges as wineries and craft breweries and reduces regulation on out-of-state sales.

Ohio

HB160 — Aid for the restaurant industry to recover from COVID-19 pandemic, the bill doubles the maximum number of Designated Outdoor Refreshment Areas (DORAs) that can be created in a municipality or township. Also allows Ohio’s small wineries to sell prepackaged food without regulation from the Ohio Department of Agriculture, creates bottle limits for micro-distilleries and permits license holders to sell alcoholic ice cream.

South Carolina

HB4963 — Amends state alcohol code, allows licensed retailers to give wine samples in excess of 16% alcohol, cordials or distilled spirits, as long as they don’t exceed a total of three liters a year.

SB993 — Amends state alcohol code to allow a permitted winery to be eligible for a special permit to sell wine at off-premise events. Also increases the amount of beer a brewery can sell to an individual per day for off-premise consumption.

South Dakota

HB1073 — Authorize special event alcohol licenses for full-service restaurant licensees.

HB1081 — Allows colleges to teach brewing beer and wine classes on South Dakota campuses to students age 21 or older. Brewing must be held off campus as the education institution is not deemed a licensed manufacturer. Any distilled spirits, malt beverage, or wine produced under this section may only be consumed for classroom instruction or research and may not be donated or sold.

Tennessee

SB2423 — Allows alcohol sales at the Memphis Zoo.

SB1123 — Encourages farmers who produce raw milk to complete a safe milk-handling course.

Utah

HB134 — Legalizes the sale of raw butter and raw cream in Utah;

HB232 — An agri-tourism bill that allows farms and ranches to host events that include food that would not need to be prepared in a commercial kitchen. Farmers must apply for a food establishment permit to use their private home kitchen.

HB399 — Changes to the Alcohol Beverage Control Act, prohibits advertising that promotes the intoxicating effects of alcohol or emphasizes the high alcohol content of an alcoholic product.

HB5010 — The COVID-19 Cultural Assistance Grant Program, which appropriates $62 million for struggling arts, cultural and recreational organizations and businesses across the state.

HB6006 — In response to the coronavirus pandemic, the bill amends the Alcohol Beverage Control Act, delaying the expiration date of the retail licenses set to expire in 2020 for places selling alcohol. Also permits alcoholic beverage licensees at international airports to change locations if needed.

Vermont

SB351 — A coronavirus relief bill which authorizes $36 million for agriculture and forestry sectors.

Washington

HB2217 — An update to Cottage Food Law eliminates the requirement that a home address must be put on a food label.

HB2412 — Increases amount of additional retail licenses for a domestic brewery or microbrewery from two to four, and directs health department to adopt rules allowing brewery owners to allow dogs on brewery premise

SB5006 — Allows sale of wine by microbrewery license holders.

SB5323 — A bill eliminating single-use, plastic carry-out bags

SB5549 — Modernizing resident distillery marketing and sales restrictions. Allows distilleries to sell products off-premise, similar to breweries and wineries.

SB6091 — Continues work on the Washington Food Policy Forum, including support for small farms and increasing the availability of food grown in the state.

West Virginia

HB4388 — Removes outdated restrictions on alcohol advertising, limiting the Alcohol Beverage Control Commissioner’s authority to restrict advertising in certain advertising mediums, such as at sporting events and highway billboards.

HB4524 — Making the entire state “wet,” permitting the off-premises sale of alcoholic liquors in every county and municipality in the state.

HB4560 — Permits licensed wine specialty shops to sell wine with a gift basket by telephonic, electronic, mobile or web-based wine ordering. Establishes requirements for lawful delivery.

HB 4697 — Removes restriction that a mini-distillery use raw agricultural products originating on the same premises

HB4882 — Allows unlicensed wineries not currently licensed or located in West Virginia to provide limited sampling and temporary, limited sales for off-premise consumption at fairs, festivals and one-day nonprofit events “in hopes that such wineries would eventually obtain a permanent winery or farm winery license in West Virginia.”

Wisconsin

HB1038 — Bans customers from returning food items during a health pandemic or emergency, dissuading people from stocking up on too many supplies.

SB83 — Increases sales volume of alcohol by retail stores from four liters per transaction to any quantity.

SB170 — Allows minors to operate temporary food stands without a permit or license.

Wyoming

HB82 — Authorizes a microbrewery to operate at more than one location. The local licensing authority may require the payment of an additional permit fee not to exceed $100.00.

HB84 — Authorizes the sale of certain homemade food items that do not require time or temperature control. These include but are not limited to:

but is not limited to, jams, uncut fruits and vegetables, pickled vegetables, hard candies, fudge, nut mixes, granola, dry soup mixes excluding meat based soup mixes, coffee beans, popcorn and baked goods that do not include dairy or meat frosting or filling or other potentially hazardous frosting or filling;

“non-potentially hazardous” (no dairy, quiches, pizzas, frozen doughs, foods that require refrigeration and cooked meat, cooked vegetables and cooked beans). Allows someone other than the producer to sell the food, as long as food is not sold in a retail location or grocery store where similar food items are displayed or sold. Food must be labeled with “food was made in a home kitchen, is not regulated or inspected and may contain allergens.”

HB158 — Allows microbreweries to make malt beverages at multiple locations rather than one as deemed in current law.

Butter or Not?

A ruling has been issued on a lawsuit against the California Department of Food & Agriculture. It will be a landmark in the vegan (and fermented) food industry. A California judge said vegan dairy company Miyoko’s Kitchen can continue using the terms “butter,” “lactose-free” and “cruelty-free” on its packaging. The state’s food and agriculture department told Miyoko’s earlier this year that those terms could not be used on the vegan butter packaging because it was confusing to consumers. They said the term butter is restricted to products containing at least 80% milk fat. But Miyoko’s butter is a cashew cream fermented with live cultures. Miyoko’s also creates the natural flavor in their products by fermenting rosemary, plum and oregano.

“The state’s showing of broad marketplace confusion around plant-based dairy alternatives is empirically underwhelming,” wrote U.S. District Judge Richard Seeborg. Miyoko’s Kitchen, he wrote, is entitled to label its products as “butter” under the protection of the First Amendment. The case has still not been dismissed.

Read more (Food Dive)

- Published in Business