Managing Fermented Food Microbes to Control Quality

Fermented foods are produced through controlled microbial growth — but how do industry professionals manage those complex microorganisms? Three panelists, each with experience in a different field and at a different scale — restaurant chef, artisanal cheesemaker and commercial food producer — shared their insights during a TFA webinar, Managing Fermented Food Microbes to Control Quality.

“Producers of fermented foods rely on microbial communities or what we often call microbiomes, these collections of bacteria yeasts and sometimes even molds to make these delicious products that we all enjoy,” says Ben Wolfe, PhD, associate professor at Tufts University, who moderator the webinar along with Maria Marco, PhD, professor at University of California, Davis (both are TFA Advisory Board members).

Wolfe continued: “Fermenters use these microbial communities every day right, they’re working with them in crocks of kimchi and sauerkraut, they’re working with them in a vat of milk as it’s gone from milk to cheese, but yet most of these microbial communities are invisible. We’re relying on these communities that we rarely can actually see or know in great detail, and so it’s this really interesting challenge of how do you manage these invisible microbial communities to consistently make delicious fermented foods.”

Three panelists joined Wolfe and Marco: Cortney Burns (chef, author and current consultant at Blue Hill at Stone Barns in New York, a farmstead restaurant), Mateo Kehler (founder and cheesemaker at Jasper Hill in Vermont, a dairy farm and creamery) and Olivia Slaugh (quality assurance manager at wildbrine | wildcreamery in California, producers of fermented vegetables and plant-based dairy).

Fermentation mishaps are not the same for producers because “each kitchen is different, each processing facility, each packaging facility, you really have to tune in to what is happening and understand the nuance within a site,” Marco notes. “Informed trial and error” is important.

The three agreed that part of the joy of working in the culinary world is creating, and mistakes are part of that process.

“We have learned a lot over the years and never by doing anything right, we’ve learned everything we know by making mistakes,” says Kehler.

One season at Jasper Hill, aspergillus molds colonized on the rinds of hard cheeses, spoiling them. The cheesemakers discovered that there had been a problem early on as the rind developed. They corrected this issue by washing the cheese more aggressively and putting it immediately into the cellar.

“For the record, I’ve had so many things go wrong,” Burns says. A koji that failed because a heating sensor moved, ferments that turned soft because the air conditioning shut off or a water kefir that became too thick when the ferment time was off. “[Microbes are] alive, so it’s a constant conversation, it’s a relationship really that we’re having with each and every one on a different level, and some of these relationships fall to the wayside or we forget about them or they don’t get the attention they need.”

Burns continues: “All these little safeguards need to be put in place in order for us to have continual success with what we’re doing, but we always learn from it. We move the sensor, we drop the temperature, we leave things for a little bit longer. That’s how we end up manipulating them, it’s just creating an environment that we know they’re going to thrive in.”

Slaugh distinguishes between what she calls “intended microbiology” — the microbes that will benefit the food you’re creating — and “unintended microbiology” — packaging defects, spoilage organisms or a contamination event.

Slaugh says one of the benefits of working with ferments at a large scale at wildbrine is the cost of routine microbiological analysis is lower. But a mistake is stressful. She recounted a time when thousands of pounds of food needed to be thrown out because of a contaminant in packaging from an ice supplier.

“Despite the fact that the manufacturer was sending us a food-grade or in some cases a medical-grade ingredient, the container does not have the same level of sanitation, so you can’t really take these things for granted,” Slaugh says.

Her recommendations include supplier oversight, a quality assurance person that can track defects and sample the product throughout fermentation and a detailed process flow diagram. That document, Slaugh advises, should go far beyond what producers use to comply with government food regulations. It should include minutiae like what scissors are used to cut open ingredient bags and the process for employees to change their gloves.

“I think this is just an incredible time to be in fermented foods,” Kehler adds. “There’s this moment now where you have the arrival of technology. The way I described being a cheesemaker when I started making cheese almost 20 years ago was it was like being a god, except you’re blind and dumb. You’re unleashing these universes of life and then wiping them out and you couldn’t see them, you could see the impacts of your actions, but you may or may not have control. What’s happened since we started making cheese is now the technology has enabled us to actually see what’s happening. I think it’s this groundbreaking moment, we have the acceleration of knowledge. We’re living in this moment where we can start to understand the things that previously could only be intuited.”

- Published in Food & Flavor, Science

Fermentation vs. Fiber — Both Help, but Fermentation Shines

A diet high in fermented foods increases microbiome diversity, lowers inflammation, and improves immune response, according to researchers at Stanford University’s School of Medicine.The groundbreaking results were published in the journal Cell.

In the clinical trial, healthy individuals were fed for 10 weeks, a diet either high in fermented foods and beverages or high in fiber. The fermented diet — which included yogurt, kefir, cottage cheese, kimchi, kombucha, fermented veggies and fermented veggie broth — led to an increase in overall microbial diversity, with stronger effects from larger servings.

“This is a stunning finding,” says Justin Sonnenburg, PhD, an associate professor of microbiology and immunology at Stanford. “It provides one of the first examples of how a simple change in diet can reproducibly remodel the microbiota across a cohort of healthy adults.”

Researchers were particularly pleased to see participants in the fermented foods diet showed less activation in four types of immune cells. There was a decrease in the levels of 19 inflammatory proteins, including interleukin 6, which is linked to rheumatoid arthritis, Type 2 diabetes and chronic stress.

“Microbiota-targeted diets can change immune status, providing a promising avenue for decreasing inflammation in healthy adults,” says Christopher Gardner, PhD, the Rehnborg Farquhar Professor and director of nutrition studies at the Stanford Prevention Research Center. “This finding was consistent across all participants in the study who were assigned to the higher fermented food group.”

Microbiota Stability vs. Diversity

Continues a press release from Stanford Medicine News Center: By contrast, none of the 19 inflammatory proteins decreased in participants assigned to a high-fiber diet rich in legumes, seeds, whole grains, nuts, vegetables and fruits. On average, the diversity of their gut microbes also remained stable.

“We expected high fiber to have a more universally beneficial effect and increase microbiota diversity,” said Erica Sonnenburg, PhD, a senior research scientist at Stanford in basic life sciences, microbiology and immunology. “The data suggest that increased fiber intake alone over a short time period is insufficient to increase microbiota diversity.”

Justin and Erica Sonnenburg and Christopher Gardner are co-authors of the study. The lead authors are Hannah Wastyk, a PhD student in bioengineering, and former postdoctoral scholar Gabriela Fragiadakis, PhD, now an assistant professor of medicine at UC-San Francisco.

A wide body of evidence has demonstrated that diet shapes the gut microbiome which, in turn, can affect the immune system and overall health. According to Gardner, low microbiome diversity has been linked to obesity and diabetes.

“We wanted to conduct a proof-of-concept study that could test whether microbiota-targeted food could be an avenue for combatting the overwhelming rise in chronic inflammatory diseases,” Gardner said.

The researchers focused on fiber and fermented foods due to previous reports of their potential health benefits. High-fiber diets have been associated with lower rates of mortality. Fermented foods are thought to help with weight maintenance and may decrease the risk of diabetes, cancer and cardiovascular disease.

The researchers analyzed blood and stool samples collected during a three-week pre-trial period, the 10 weeks of the diet, and a four-week period after the diet when the participants ate as they chose.

The findings paint a nuanced picture of the influence of diet on gut microbes and immune status. Those who increased their consumption of fermented foods showed effects consistent with prior research showing that short-term changes in diet can rapidly alter the gut microbiome. The limited changes in the microbiome for the high-fiber group dovetailed with previous reports of the resilience of the human microbiome over short time periods.

Designing a suite of dietary and microbial strategies

The results also showed that greater fiber intake led to more carbohydrates in stool samples, pointing to incomplete fiber degradation by gut microbes. These findings are consistent with research suggesting that the microbiome of a person living in the industrialized world is depleted of fiber-degrading microbes.

“It is possible that a longer intervention would have allowed for the microbiota to adequately adapt to the increase in fiber consumption,” Erica Sonnenburg said. “Alternatively, the deliberate introduction of fiber-consuming microbes may be required to increase the microbiota’s capacity to break down the carbohydrates.”

In addition to exploring these possibilities, the researchers plan to conduct studies in mice to investigate the molecular mechanisms by which diets alter the microbiome and reduce inflammatory proteins. They also aim to test whether high-fiber and fermented foods synergize to influence the microbiome and immune system of humans. Another goal is to examine whether the consumption of fermented foods decreases inflammation or improves other health markers in patients with immunological and metabolic diseases, in pregnant women, or in older individuals.

“There are many more ways to target the microbiome with food and supplements, and we hope to continue to investigate how different diets, probiotics and prebiotics impact the microbiome and health in different groups,” Justin Sonnenburg said.

Other Stanford co-authors are Dalia Perelman, health educator; former graduate students Dylan Dahan, PhD, and Carlos Gonzalez, PhD; graduate student Bryan Merrill; former research assistant Madeline Topf; postdoctoral scholars William Van Treuren, PhD, and Shuo Han, PhD; Jennifer Robinson, PhD, administrative director of the Community Health and Prevention Research Master’s Program and program manager of the Nutrition Studies Group; and Joshua Elias, PhD.

Researchers from the nonprofit research center Chan-Zuckerberg Biohub also contributed to the study. Here’s the complete press release from Stanford Medicine News Center.

Which Are Healthier — Fermented or Acidified Pickles?

Researchers with the USDA have found that fermented cucumber pickles contain more of the naturally-occurring gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) than do their acidified counterparts. Results of this study of commercially-available pickles were recently published in the Journal of Food Composition and Analysis.

GABA works as a neurotransmitter in the brain. It has been scientifically proven that GABA, when consumed in foods or supplements, reduces blood pressure, improves decision making, reduces anxiety and boosts immunity.

Fermented cucumber pickles undergo a lactic acid fermentation, whereas acidified cucumber pickles are submerged in an acidic brine. The fermented pickles with the most GABA were made in a low-salt fermentation, and the products were prepared for direct consumption. GABA content also was found to remain stable during storage for fermented cucumbers.

“Worldwide, people are interested in consuming fermented foods as part of a healthy lifestyle. Most often, we associate the healthfulness of fermented foods with probiotic microbes. But many fermented foods contain few to no microbes when consumed,” said Jennifer Fideler Moore, North Carolina State University graduate research assistant and one of the study co-authors, in a USDA-ARS press release. “Our research shows that the health-promoting potential of lactic acid fermented cucumbers reaches far beyond the world of probiotics. This opens the door to more research into health-promoting compounds made during fermentation of fruits and vegetables.”

Adds Suzanne Johanningsmeier, study co-author and USDA Agricultural Research Service (USDA-ARS) Research Food Technologist: “Fruits and vegetables are made up of thousands of unique molecules. These molecules rule the flavor, texture, and nutritional value, but it is difficult to study them in such complex systems. To tackle this problem, we use advanced analytical chemistry techniques like mass spectrometry to study food molecules and figure out the best food processing methods for improved quality of fruit and vegetable products.”

[Johanningsmeier presented further details of the study during a TFA webinar.]Korea’s Controversial Kimchi Book

As China and Korea continue to clash over where kimchi originated, the Korean government has published a book laying their claim.

“Kimchi in the Eyes of the World” contains history, recipes, stories from writers who love to eat kimchi, and how traditional Korean kimchi is different from China’s pao cai, a pickled vegetable dish.

The 148-page book was published by the Korean Culture and Information Service and the Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs. They plan to distribute it in Korean- and English-language versions through overseas Korean Culture Centers and via the foreign embassies in Korea.

Read more (The Korea Herald)

- Published in Business, Food & Flavor

Study: Can Fermented Veggies Impact Health?

Is there a connection between a happy gut and a healthy heart? The University of North Florida Department of Nutrition and Dietetics is conducting a study to determine what impact a diet rich in fermented vegetables has on cardiovascular disease and markers of inflammation.

Participants will be placed in two groups — the first consumes their regular diet for eight weeks, then receives fermented vegetables at the end of the study. The second will eat a half cup of fermented vegetables every day for eight weeks.

“These studies are the only way nutritionists can determine if certain foods can help with prevention and/or treatment of common health problems faced by our community, such as cardiovascular disease,” says Dr. Andrea Arikawa, associate professor at the university.

Read more (University of North Florida)

“Strategic Rotting”

Fermentation saved the human diet, argues Krish Ashok, author of Masala Lab: The Science of Indian Cooking. He calls fermentation strategic rotting. The discovery of fire was key to the human’s survival as they learned to cook meat, but fermentation allowed civilization to create bread and alcohol, turn milk into yogurt and preserve a harvest through the winter.

“Fast forward a few millennia, and we have mastered fermentation to the point where we can pick and choose microbes with precision and generate complex flavours in the bargain,” Ashok writes. Pictured, his charming drawings illustrate microbes used in fermentation.

Read more (Mint Lounge)

- Published in Food & Flavor

The Safety of Fermented Food

Thanks to lactic acid — which kills harmful bacteria during fermentation — fermented foods are arguably among the safest foods that humans eat. But if critical errors are made, there is the risk of food safety hazards.

“When we talk about fruit and vegetable ferments, there is a very long history of microbial safety with traditionally fermented fruits and vegetables,” says Erin DiCaprio, extension specialist at University of California, Davis, Department of Food Science and Technology. “While outbreaks associated with fermented fruits and vegetables are rare, vegetable and fruit fermentation is not without risk.”

DiCaprio, a food safety expert, detailed proper food safety protocols during a webinar for EATLAC, a UC Davis project putting scientific knowledge and research behind fermentation. DiCaprio shared two documented instances of fermented foods causing a foodborne illness, both from small-scale batches of kimchi. But she emphasized that, when all food safety concerns are mitigated, fermented foods do not pose a risk.

“From the food microbiology standpoint, bacteria really are the most important group of microorganisms because bacteria, certain types of bacteria, are a food safety concern,” she adds. “There are many different types of bacteria that contribute to food spoilage and, of course, there are specific types of bacteria that are used beneficially for fermentation.”

What happens during fermentation that makes food safe? Lactic acid bacteria are created, which convert sugars into lactic acid, acetic acid and CO2. Those antimicrobial compounds help fight off pathogens, competing with other microbes for nutrition sources.

Biological hazards — bacteria, viruses and parasites that can cause foodborne illnesses — are the biggest concerns. Botulism, E. coli and salmonella are the main hazards for fermented foods. Botulism can form in oxygen-free conditions if a fermentation is not successful and acid levels are too low. E. coli and salmonella form when sanitation practices are not followed.

“Commercially, when someone is developing a valid fermentation process, they are typically going to be looking to see that sufficient acid is produced during fermentation, to inactivate some of these acid tolerant (bacteria),” DiCaprio says. “Our traditional vegetable fermentations — things like fermented cucumber, sauerkraut, kimchi — they’ve all been shown to produce sufficient acid to inactivate the sugar toxin producing e-coli, so from a safety standpoint, sufficient acid production is the critical control point for ensuring the safety of a fermented fruit or vegetable. “

There are seven critical factors to keep a ferment safe:

- High-quality, raw ingredients. “If there are a high number of spoilage microorganisms to start with, it will be really difficult for the lactic acid bacteria to dominate the fermentation,” DiCaprio says.

- Research-based recipe. Following a tested recipe ensures the proper balance of ingredients to keep the food safe.

- Proper sanitation. Cleaning of all utensils and surfaces ensures no pathogens will contaminate the food. This mitigates cross-contamination risk, too.

- Preparation of ingredients. Food particles should be uniform in size, either cut in small slices or shredded. Smaller pieces release more water and nutrients, promoting the growth of lactic acid bacteria.

- Salt concentration. Lactic acid bacteria thrive in a salt brine. The key amount: anywhere from 1-15% salt brine by weight of the ferment.

- Appropriate temperature. A temperature between 65-75 degrees fahrenheit is ideal to keep spoilage microorganisms at bay.

- Adequate time. “It takes a while for significant acid to be produced, so be patient and follow the directions in the recipe,” DiCaprio advises. Most fruit and vegetable ferments take 3-6 weeks to be completed.

Ugly Delicious

A unique business practice has been developed in Montana by Farmented Foods — the company ferments discarded produce from local growers to fill their jars with the likes of radish kimchi, dill sauerkraut and spicy carrot chips. The co-owners (Vanessa Walsten and Vanessa Williamson) met in 2016 at a Farm to Market class at Montana State University. They are currently getting ready to renovate a former cafe into a fermentation kitchen, thanks to a grant from the Montana Agriculture Development Council.

“Every year, so much produce is wasted because we don’t deem it perfect enough,” says Williamson, adding that the company “was founded initially to help farmers eliminate unnecessary food loss on their farms in the form of ugly and excess crops.”

They estimate they’ve saved over 6,000 pounds of imperfect produce.

Read more (Daily Inter Lake)

- Published in Business

Solving Illnesses with Fermentation?

Scientists in Russia and Egypt have developed a functional drink that’s been proven to combat anemia and malnutrition. The juice is made from beet extract, milk and probiotic bacterial strains. The scientists developed a quinoa bread, too. The goal is to keep the beverage and bread affordably priced and get them offered at grocery stores internationally.

“One should bear in mind that we are not creating a medicine, but a natural, functional food product,” said Sobhi Ahmed Azab Al-Suhaimi, professor in the Department of Technology at South Ural State University (SUSU) in Russia. “However, this juice can make up for the lack of iron, zinc, manganese and calcium in the body. One serving of the drink will contain the whole rate [sic] of minerals. Its carbohydrate content is low. Fermented juice will help to overcome anemia and to improve digestion due to probiotics.”

Scientists at SUSU worked with scientists at the University of Alexandria in Egypt. Their findings were published in the Journal of Food Processing and Preservation and Plants.

Read more (Phys.org)

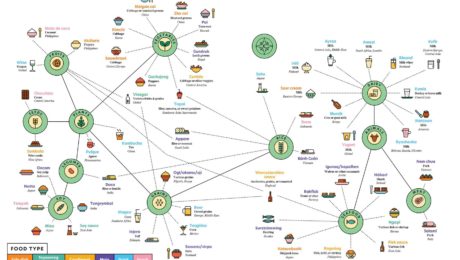

The World of Fermented Foods

In the latest issue of Popular Science, a creative infographic illustrates “the wonderful world of fermented foods on one delicious chart.” It represents “a sampling of the treats our species brines, brews, cures, and cultures around the world,” and is particularly interesting as it shows mainstream media catching on to fermentation’s renaissance. Fermentation fit with the issue’s theme of transformation in the wake of the pandemic.

Read more (Popular Science)

- Published in Food & Flavor