Development of Pickling Technologies & Products

There’s a void in scientific knowledge of fermented and pickled vegetables, and scientists are just starting to scratch the surface.

“We have a wealth of chemical compositions that we still don’t fully understand,” says Dr. Ilenyz Pérez-Díaz, PhD, a microbiologist with the USDA-ARS. Perez-Diaz presented on “Development of Pickling Technologies & Products” during a webinar hosted by TFA. “I honestly think there is still a lot to do in regards to the richness of the biological functions that are present in these systems. Every vegetable is different. … It will be fantastic to be able to comprehensively understand what’s really there and how we can use it for the benefit of not only processing but also for the benefit of human health.”

The purpose of the USDA-ARS is to find solutions for agricultural challenges, domestically and globally. In 2019, the 8,000 employees of the USDA-ARS researched 660 agricultural projects, filed 85 new patents, issued 65 new patents, received 51 new licenses and wrote 3,816 peer-reviewed journal articles.

Pérez-Díaz is assigned to the food science and market quality and handling research unit. There the team develops state-of-the-art, science-backed methods that improve the post-harvest processes, food preservation, food quality and safety and, ultimately, introducing nutritious products into the food system.

“What I love about the research that she’s doing is that pickling and fermentation are these ancient, traditional technologies that people have been using for hundreds and hundreds of years, and she’s really thinking about ways that we can advance those technologies using all the amazing sequencing and all the microbiology we have today,” says Ben Wolfe, PhD, associate professor of biology at Tufts University, and the TFA Advisory Board member who moderated the webinar.

Pérez-Díaz shared the USDA’s latest technologies to reduce food waste, lessen environmental impacts, improve water/energy demand and add more health value to preserved vegetables. Here are highlights from the research presented, focused on addressing two key problems:

Eliminate Salt in Cucumber Fermentation

PROBLEM: Sodium chloride is essential to fermentation, but the salt-rich (and sometimes preservative-filled) brine shipped from overseas producers can get into local freshwater supplies. There are no growers of small cucumbers (gherkins) in the U.S., so food projects that require small cucumbers must use overseas produce. But, in order for the cucumbers to be transported, they must be fermented or pickled. High amounts of salt, acid and sometimes preservatives are added, and these potentially can damage the water supply.

SOLUTION: USDA-ARS tested fermenting pickles using three popular spices: dill, cinnamon and mustard seed. But, though salt was reduced or eliminated, “the indigenious microbiota is always there,” Pérez-Díaz explains. “The salt is modulating the activity within this population. It tends to favor the lactic acid bacteria. But what I’ve learned is it is not the main factor modulating that microbiota. The ph and the production of that lactic acid and or acetic acid is really the factor in excluding the non desirable microorganisms and favoring the fermentative microbiota.”

Reduce Food Waste by Creating Foods

PROBLEM: In the U.S., between 30-70% of fresh vegetable produce is wasted. “Those are alarming numbers,” says Pérez-Díaz. “Even though they are estimates, it is necessary to look at ways to resolve the impact of such waste.”

SOLUTION: The USDA developed small-scale fermentation systems for use in restaurants, farmer’s markets and grocery stores. These vessels make fermenting excess food more manageable by allowing easy fermentation of smaller batches.

“We can convert what was waste or surplus or defective vegetables into a value-added product,” Pérez-Díaz says. “It will be a probiotic product, it will be fermented vegetables auxiliaries that can be used as sources of flavor, colors, ingredients in a number of recipes or even dehydrated for different applications.” [This project was near completion before the pandemic and is expected to pick-up soon.]

Fermentation, she emphasized, is needed to sustain a modern food system.

“These fermentations, if applied properly, they are very powerful eliminating the organisms that are not desirable or the organisms that are not of health significance,” Pérez-Díaz says. “I think fermentation will truly be an important component as we move forward to that new era.”

- Published in Science

Science Behind Fermented Vegetable Safety

Just because vegetables were fermented does not make them immune to harmful bacteria like E. coli. Though fermentation improves food safety, the quality of the raw vegetable before it’s fermented is extremely important.

“The issue of fermentation safety is one that comes up a lot. People are getting excited about the fermentation world these days, fermentation is increasing in popularity…(but) the wheels can fall off if you’re not careful,” says Fred Breidt, PhD, a USDA microbiologist. Breidt spoke during a recent webinar hosted by The Fermentation Association, “The Science Behind the Safety of Fermented Vegetables.” “The moral of the story: if the vegetables were safe to eat before you ferment them, they’re going to be safe to eat after you ferment them. If they’re not, you’ve got to ferment them for a long time to make sure they’re safe.”

An outbreak of dangerous bacteria in fermented vegetables, “it’s going to be pretty rare that that happens,” Breidt stresses. But, without proper sanitation protocol and vegetable quality control, pathogenic “bad guys” can flourish, like E. coli, salmonella and listeria. E. coli is more common in vegetables because it’s extremely acid resistant, and can survive for long periods of time at low pH levels and cold temperatures.

“Just washing the surface (of the vegetable) isn’t always going to do the trick,” Breidt says. “You don’t have to eat very much to get sick.”

An E. coli outbreak in kimchi made 230 Korean school children sick in 2013. The children, from seven different schools, all ate fermented kimchi made by the same manufacturer.

“If the folks had eaten the cabbage that this kimchi was made out of, they would have gotten sick as well,” Breidt says. “Was the cabbage improved in the sense of maybe it had fewer E. coli on it because of fermentation? Yes. But there was still enough when this was eaten to make a lot of people sick.”

“You can’t rely on salt for safety is the point,” he adds. “It does encourage the lactic acid bacteria and it helps them grow and it will increase overall the safety of your fermentation.”

David Ehreth, president and founder of Alexander Valley Gourmet, parent company of Sonoma Brinery, moderated the webinar. Ehreth first met Breidt when Sonoma Brinery made a few tons of sauerkraut that became infected with yeast. Ehreth says “I called Ghostbusters, and that’s Fred Breidt.” Though yeast is different from a pathogen like E. coli, Ehreth said Sonoma Brinery has managed to control yeast over the years by careful management of production techniques and improved sanitation methods.

- Published in Science

Study Links Low COVID Mortality to Fermented Veggies

A new study links lower COVID-19 deaths to countries where the diet is rich in fermented vegetables. Researchers in Europe found in countries where the national consumption of fermented vegetables is high, the mortality risk for COVID-19 decreased by 35.4%. Results are currently preliminary and undergoing peer review. But, if the hypothesis is confirmed, “COVID-19 will be the first infectious disease epidemic to involve biological mechanisms that are associated with a loss of ‘nature,'” reads an article in News Medical. “Significant changes in the microbiome caused by modern life and less fermented food consumption may have increased the spread or severity of the disease, (researchers) say.”

The study was led by Dr. Jean Bousquet, a professor of pulmonary medicine at Montpellier University in France. After researching that diet may play a big role in determining how well people can fight the coronavirus, Bousquet says he now eats fermented foods multiple times a week.

Read more (News Medical Life Sciences)

Q&A with Author and Fermentation Expert

How to make fermentation practical for modern people? That’s a culinary goal Alex Lewin is passionate about reaching. Lewin is the author of “Real Food Fermentation” and “Kombucha, Kefir, and Beyond” (and member of TFA’s Advisory Board). His mission is “lowering barriers to fermentation.”

“Most of the ways we control the environment is lowering the barrier of fermentation for the microbes, like adding salt to the cabbage or keeping yogurt at the right temperature,” Lewin says. “But a lot of what I’m doing is lowering the barrier of fermentation for the humans.”

Lewin began fermenting as a hobby, and it turned into a passionate side career. Lewin works in the tech industry for his day job, then spends his spare time immersed in fermentation projects. His schedule parallels his interests. Lewin studied math at Harvard University, then studied cooking at the Cambridge School of Culinary Arts. He’s often tinkering with a microbe-rich condiment in the kitchen after office hours, and attending new fermentation conferences during his vacation time.

“Fermentation gives me direction in my life, but there’s also something about tech that nourishes me. And I don’t have to choose,” Lewin says. “The fermentation world, it is a huge amount of community. The community of fermenters really reflects the community of microbes. There’s some very interesting, very open-minded people who are outside of the mainstream in the fermentation world. And a lot of them feel they have a calling, that they were called to do this.”

Below, excerpts from a Q&A with Lewin from his home in California’s Bay Area:

The Fermentation Association: What got you first interested in fermentation?

Alex Lewin: I’d always been interested in food and started cooking a little in college. My dad had heart disease and later diabetes and he was on these diets and pills, but things didn’t seem to be getting him any better. When I got interested in health and nutrition during this time, I partly did it out of fear for my own life.

I started reading books about health, nutrition, diet, food. What struck me was they all said different things. I had studied math, physics, and generally the experts agree more or less on the obvious stuff. There’s discussion on the origin of the universe, yes, but no disagreement about what happens when you drop something and it hits the floor. I was surprised at the difference. One cookbook would say what would really matter in your health is your blood type — another would say the ratio from carbs to fat to protein that you eat, you have to eat them at a certain ratio at every meal. Then another book says don’t eat protein and carbs together, have space between them. I would read and was intrigued and frustrated. I had this idea that it should make sense and it didn’t make sense.

I was in a bookstore one day and I saw the book “The Revolution Will Not Be Microwaved” and thought it was such a fantastic title. It was about food politics and underground food movements and food subcultures. It was written by Sandor Katz and he writes with so much heart, very intelligently. He writes about radical food politics and has this way of keeping it very balanced and measured. Some books about radical politics can be shrill, but there’s nothing shrill or strident about anything Sandor does.

I wanted to read what else Sandor had written and found “Wild Fermentation,” and made my first jar of sauerkraut. In the meantime, there’s another book that affected me a lot, “Nourishing Traditions” by Sally Fallon. And that book similarly blew my mind. That book took all these diverse threads of diet, health and nutrition and pulled them all together in a way no other book has or has since. I felt like I finally understood what to eat, where before it was a free-for-all.

One of the things I learned to think about when you’re eating are foods with enzymes, microbes and live foods that weren’t processed with modern processing techniques. That really set me on my path.

TFA: After that, you spent the next decade diving into fermentation. You went to cooking school, started teaching fermentation classes, got involved with the Boston Public Market Association. How did your book “Real Food Fermentation” come about?

Lewin: A friend of mine who had a chocolate business recommended me to a book publisher. That was for “Real Food Fermentation,” my first book, in which I made it as easy as possible for people to ferment things. I knew from my class, making sauerkraut is not very complicated, and once people see it and how easy it is, they’re likely to keep doing it. So in my book, there are lots of pictures. There are lots of people with kitchen anxiety who are more comfortable if they see pictures of everything — pictures of me slicing the cabbage and putting it in the jar. I’m not a visual learner, I want to see words and measurements and numbers. So the book has both.

As time went on, I ended up meeting Raquel Guajardo (co-author for Lewin’s book “Kombucha, Kefir, and Beyond), and we decided to write a book about fermented drinks. I think it’s a great book because we both got a chance to share our ideas about food and health and what is happening in the world. Then we got to share recipes from my experience and her experience as a fermented drink producer in Mexico, where some of the pre-Hispanic traditions are very much alive.

Fermented drinks I think are also easier. They’re a little less weird to people than sauerkraut and kimchi, they’re less intimidating. We all drink things that are fizzy, sweet and sour. But like kimchi, it is so far outside of the usual experience of eating. Most people know they shouldn’t drink five Coca-Colas a day, so fermented drinks are the answer.

TFA: Tell me more about your goal to lower the barrier into fermentation.

Lewin: What is it about kombucha that is familiar? It’s fizzy, sweet and sour. What is soda? It’s fizzy, sweet and sour. I’m certainly not the first to observe that, but I’m connecting the dots on how we can integrate these ancient foods into our modern lives.

For me, I always considered myself an atheist. Then when I started fermenting, I started letting go and thinking there are things outside of our control and we just need to accept them. There are things we will never understand completely, there are forces we don’t even know about. I came to faith and spirituality through the practice of fermentation.

A lot of the problems that we face today have been created by application of high technology to the food system, then we try to solve them by using more food technology — like growing fake meat. The problems caused by high tech are not going to be solved by high tech, they’ll be solved by low tech. And fermentation is one of my favorite low tech technologies. You pretty much just need a knife.

Fermentation also gets away from the western, scientific, medical paradigm that’s so reductionist, where we’re looking for some small isolated problem in the body and then trying to counter it. Looking for some metabolic issue and trying to neutralize the symptoms. “Your blood pressure is high, let’s lower it with a pill.” If the underlying causes of all these things are eating bad food, trying to attack the symptoms one at a time is not the easiest way to make progress. We have to move away from this reductionist mindset where we’re playing whack-a-mole with our symptoms. We’re healthier looking for the underlying problems and addressing them.

Gut health is a big one. All sorts of other problems caused by high-tech, processed foods. Eastern medicine has more of an idea of holistic health, what’s going on in the system. I think that’s the future. I think a lot of the health problems will be solved through system-type thinking. This balance of energy. There’s a dynamic of equilibrium in our gut.

TFA: You mentioned Sandor Katz’ book “Wild Fermentation” introducing you to fermentation. What about his book appealed to you?

Lewin: There’s something rebellious about making food and leaving it out on the counter. I hadn’t been to cooking school yet at that point when I read it. But you read about food safety and there are rules, you can only leave food on the counter for so long at this temperature. There are all these things you’re not supposed to do with food. But in order to ferment, you have to violate these rules to grow the microbes. There’s something rebellious about fermentation.

Another part of it is the utterly low tech aspect to it. All the trouble we go to to process our food in high tech ways today, turns out we can do it better without preservatives, without heat packing things, without the refrigerator.

When you ferment something, every time it’s a little different. And you can keep doing it again and it doesn’t matter if it wasn’t perfect. And a lot of times you can do something interesting with it. I made pickles the other day, they turned out soft, so I’m going to make them into relish. Too much sourdough starter? Turn it into a porridge. Your kombucha got too sour? Turn it into vinegar. Sometimes something can be ruined, but often you can turn it into something else. Being able to make kombucha that’s better than most of the store-bought kombucha is pretty cool — I discovered that ability.

TFA: Why do you encourage people to incorporate fermented foods in their modern diet?

Lewin: One of them is just coming back to the kitchen. During the coronavirus pandemic, people are coming back to their kitchens. That’s an unqualifiedly good thing, it means that much less processed food and that much less fast food. Fermentation also brings people back into the kitchen. And fermentation is in the limelight during the pandemic. Especially sourdough right now. Fermented projects are great things to do with families, kids. When you talk to the older generation about making sourdough, pickles, bread, they have these stories. My mom never made pickles, but her father did. It’s not too late to get these stories. Food is one of the things that connects generations of people, that reminds us of our roots and grounds us, literally.

Making anything with your hands, it’s a cure for all sorts of things. Not even getting into physical, digestive health. Just making something and liking it is psychologically healthy. You feel empowered in the face of so many disempowering things. If you can turn cabbage into sauerkraut, you have power.

And then there are all the concrete, physical health benefits of eating fermented foods. You get more enzymes, more vitamins, more microbes, you get more of the good microbes and fewer of the bad microbes. You get probably less processed food, less sugar, you get all these trace substances that you really don’t get from processed food. Like nattokinase, which is this enzyme you only find in natto and might protect against heart disease and cancer. Depending on the ingredients you use when fermenting, if you use the right salt and right sweeteners, you can get minerals. Fermenting in some cases creates vitamins. You can straighten out a lot of digestive problems in my experience by introducing fermented foods, gradually.

TFA: You’ve watched Americans’ diets adapt (or not adapt) over the past few decades to changing health standards. How have Americans’ perception of fermented food and drink changed in that time?

Lewin: Americans are absolutely more accepting of it. The story of kombucha is a good one. You can follow annual kombucha sales. You used to say “kombucha” and people would say “Ew” or “What’s that?” or “My crazy aunt makes that.” Now, it’s a billion dollar business. You can get it in mainstream supermarkets in most of the country, it’s not a fringe thing anymore. Fermentation is coming to the mainstream. Kimchi is not a fringe thing. I think the rise of food culture, with food reality TV shows, has really helped fermented things like kimchi. When food trucks in LA started having kimchi and Korean BBQ tacos, for me I felt like something had turned the corner. The rise of microbreweries and the interest in natural wines and the movement away from like super-oaky chardonnays and ginormous reds to more natural wines. I think people are a lot more sophisticated about food than they were 20 years ago, and a lot of that is leading to increased interest in fermented foods.

Fermented foods are no longer fringe. We’ve come a long way in 20 years. Kombucha and kimchi are two of the flag bearers of fermentation. I think fermentation is on the rise. People will say “I think it’s just a fad,” and I’ll say “It’s absolutely not a fad.” People were fermenting 10,000 years ago. It never left. Every drop of alcohol you’re drinking, that’s fermented. It never went away, it was under the surface and now it’s on the surface again. People are just realizing it’s important.

TFA: Where do you see the future of the industry for fermented products?

Lewin: I think the more people ferment at home, the more people are going to want to buy fermented things. The more people ferment at home, the more they’ll appreciate fermented products and seek them out. It’s not like there’s a competition between home fermenting and commercial producers. If anything, there’s a symbiosis. I’ll make kimchi sometimes, but I’ll buy it sometimes, too, because it’s messy and there are people that make very good kimchi. Same with kombucha or high alcohol kombucha. I could make it if I wanted to, but it requires time and patience. Miso is another example, I don’t have the patience to wait six months to make miso.

- Published in Food & Flavor

Why are Sauerkraut and Kimchi Sales Up During the Pandemic?

People are turning to acidic dishes like sauerkraut and kimchi to protect themselves from the COVID-19 virus. Though there is no scientific evidence that foods like kimchi and sauerkraut will prevent spread of the virus, sales are booming. Health experts say it’s because cabbage is a superfood filled with antioxidants and vitamin C, and the fermented condiments are filled with probiotics that support the gut microbiome. Consumers are hypothesizing that coronavirus death rates in Germany and South Korea because sauerkraut and kimchi are traditional food staples in the two countries. In January, South Korea’s national health ministry issued a press release stressing that kimchi offers no protection against the virus. That hasn’t stopped Americans from buying it – sauerkraut sales surged 960% in March, while kimchi sales jumped 952% in February.

Doctors emphasize that the best way to prevent coronavirus infection is to avoid becoming exposed. Hand washing, social distancing and mask wearing are encouraged.

Read more (New York Post)

Burma Superstar’s Signature Fermented Tea Leaf Salad

One of the signature dishes at the Burma Superstar Restaurant group in San Francisco is the fermented tea leaf salad, also known as “laphet thoke.” The fermented tea leaves come straight from Burma (Myanmar), a legacy important to Desmond Tan, founder and owner of the restaurant group. He worked for years to source organic, uncontaminated leaves, a major change to Burma’s tea leaf industry. Leaves were formerly notoriously tainted with clothing dyes and plagued with horrible trade practices. The tea leaves take 2-6 months to ferment, resulting in a uniquely sour leaf. Burma Superstar had made a natural tea leaf dressing to enhance the flavors of the tea leaf.

Read more (Forbes)

- Published in Food & Flavor

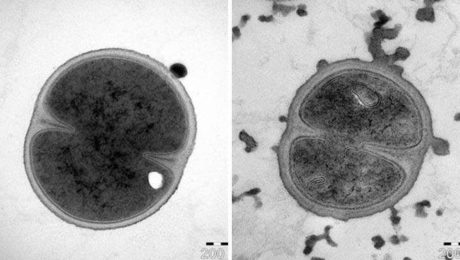

Peptide Found on Fermented Veggies Aids Antibiotics Research

Microbiologists in Sweden discovered a major breakthrough in antibiotics. Their research found an antibacterial peptide, plantarcin, can be combined with antibiotics to kill the staphylococcus bacteria (MRSA). Staph is a major problem in healthcare, which causes difficult wound infections and, in severe cases, sepsis. This plantarcin peptide comes from good bacteria — it’s found on fermented vegetables, which serve as a natural preservative for the food. The results of the study were published in the journal Scientific Reports. “Administering lower doses of antibiotics when treating infections in turn reduces the risk of further development of antibiotic resistance, which today is a major global threat to public health,” says Torbjörn Bengtsson, professor in medical cell biology at Örebro University.

Read more (Phys.org)

Fermenting Techniques of Three Northern California Sauerkraut Makers Highlighted

Who is enjoying some sauerkraut at their July 4th BBQs? Pacific Sun magazine featured three Northern California sauerkraut makers — Sonoma Brinery, Wildbrine and Wild West Ferments. The article highlights the different fermenting techniques of the three brands and features this fascinating insight from David Ehreth, president and managing partner at Sonoma Brinery:

“If I can go nerd on you for a moment,” Ehreth warns, before diving into a synopsis about the lactobacillus bacteria that exist on the surface of all fresh vegetables. “You can’t remove them by washing.” What’s more, they immediately begin to feed and reproduce — but not in a bad way, unless they’re a bad actor, he insists.

“Those bacteria will really stake out their turf,” says Ehreth. “They’re very territorial. They go to war with each other.” The incredible part of it is that the four horsemen of the food industry — listeria, E. Coli, botulinum, and salmonella—are on lactobacilli’s hit list. None survive. Five bacteria enter — one bacterium leaves.

Quoting the Food and Drug Administration, Ehreth states, “There has been no documented transmission of pathogens by fermented vegetables.”

Read more (Pacific Sun)

- Published in Science

Sandor Katz on the Fermentation Phenomenon

It’s absurd to call fermentation a new food trend, says Sandor Ellix Katz, author of “The Art of Fermentation” and “Wild Fermentation.” Fermenting practices date back to early man. But, after decades of active pasteurization and a war on bacteria, fermentation is experiencing an awareness as a food phenomenon, Katz says.

Katz – who calls himself Sandorkraut, the fermentation revivalist – spoke at a TEDx Talk in Sao Paulo on wild fermentation and the power of bacteria. Coffee, bread, cheese, beer, wine – Katz points to these as examples of “the greatest delicacies that people around the world enjoy, products of fermentation that have never gone out of style and have not recently just come into style.”

No one needs to master biology or study microorganisms to practice fermentation, Katz stresses. Before microbiology became a field, fermentation historically was viewed as mysterious or mythical because no one understood the mechanisms of it. He adds: “I cannot find one single example of a culinary tradition anywhere the does not incorporate fermentation.”

Microbiology has illuminated and harmed fermentation. For decades, the information surrounding bacteria and microorganisms was negative. People were taught the dangers of bacteria and disease – and grew to fear fermentation. But discoveries in microbiology also found that everything we eat, plant and animal, is populated by microorganisms. All life is descended and created from bacteria.

“In a way, we’re bacteria super structures,” Katz said. “For the first time, from the scientific analysis, we began to understand that fermentation is the transformative action of microorganisms.”

Fermentation often gets a bad reputation because people consider fermenting the process rotten or spoiled food. But fermentation is manipulating environmental conditions to encourage the growth of good organisms and discourage the growth of bad organisms, Katz explains.

“Fermentation is making food that is more stable than the raw product of agriculture that we began with,” Katz says. “We’re creating something that is more delicious, we’re creating something that is more easily digestible, we’re creating something where some toxic compound in the food and the otherwise dangerous food is made safe.”

For the first time in history, science is revealing the benefit of eating the live bacteria in fermented foods. The prevalence of antibiotic drugs, antibacterial cleaning products and chlorinated water now kill all bacteria in food. This war on bacteria narrows the diversity of bacteria in our intestines, Katz points out.

“If they were to kill all those microorganisms, we couldn’t possibly exist because we rely on those microorganisms for our digestion, for our immune system, our ability to withstand disease our brain chemistry,” he says. “Yet this chemical exposure…narrows biodiversity that we have inside of us.”

Katz focuses his work on public education of fermentation, helping shed light on its safety and effectiveness. More people today are seeking fermented foods because of the growing recognition of the benefits fermentation, Katz says. He teaches that the greatest benefit of fermented products are the bacteria themselves. Eating fermented foods – foods that haven’t been cooked or heat processed, since that kills the bacteria – restores the biodiversity in our intestines.

“In addition to being this important mode of transformation of food and beverages which enables people to make effective use of the food resources that are available to them, fermentation is also an engine of social change. And all of us are the starter cultures,” Katz said.

- Published in Food & Flavor, Science

Use of Pickled Onions Increases 191% in U.S. Restaurants

The use of pickled onions in U.S. restaurants and diners has grown 191% in the last four years. – Datassential.

The Fermentation Association (TFA), getting more people to enjoy fermented products. Join us at fermentationassociation.org .

- Published in Business, Food & Flavor