Highlights from TFA’s Member Survey

The Fermentation Association recently surveyed our community to better understand who has engaged with us, how their businesses are doing and to gauge the impact of the pandemic. We want to share the very interesting results.

A few qualifying comments first, however. This survey should not be interpreted as producing a profile of the fermented industry — it reached only those with whom we have connected since TFA was launched in 2017. This group is heavily weighted to Food and Beverage Producers and those in the Science, Health and Research fields. And, even as we note surprisingly high response rates below, the quantities of responses to certain questions were small and would not meet standard analytical thresholds of statistical significance. So please treat the comments and conclusions that follow as directional rather than definitive.

We received 450 full or partial responses — nearly twice the number we had expected and what we would have considered “good.” Not surprisingly, the bulk of these were from Food and Beverage Producers — just under half — with a strong representation of the Science, Health and Research community, a little less than one-fifth. The balance of the respondents were classified as Supplier or Service Provider (9%); Chef/Writer/Educator (8%); Retailer/Distributor/Broker (3%); Food Service/Hospitality (3%); or fell into a miscellaneous Other category (12%).

We will be presenting further analyses and follow-up discussions in the coming weeks. This article focuses on the two largest segments: first, Food & Beverage Producers; then, Science, Health, and Research.

FOOD & BEVERAGE PRODUCERS

- We found that over 80% of our Producers are small businesses with 25 or fewer employees, and 65% had 2020 sales of less than $500,000. That said, over 11% of the companies represented are toward the other end of the spectrum, with 100 or more on staff, and 13% with revenue of over $10 million.

- We reach a lot of Owners/Founders/Senior Executives, over 70% of respondents. The next most well-represented functional areas are Operations and Product Development.

- These businesses are spread across the developmental timeline — a little over 40% are selling at the local level, or earlier in their growth cycle (selling at farmers market or still in testing/pre-launch mode). Yet 45% are selling regionally, nationally or internationally.

- Retail is still the largest (45%) channel of sale for these producers, but Direct-to-Consumer (DTC) is just slightly behind at 40%, with the remaining 15% through Food Service/Hospitality.

- Sauerkraut/Kimchi, Pickles, Condiments/Sauces and Kombucha were the most frequently-listed product categories, each mentioned by more than 20% of the producers. Kefir, Vinegar/Shrubs, Wine and Miso also were mentioned often. Of the 25 product categories listed, we had respondents involved in every one — except poor, slimy, and unrepresented natto.

- Nearly half of producers selling at retail and/or DTC had sales gains in 2020 and another third maintained their revenues. Not surprisingly, nearly 40% of producers selling into food service saw sales take a hit — only 15% reported gains.

- The Covid-19 pandemic caused a host of issues for producers, though their prevalence seemed to vary depending on the size of the company. Among larger producers, over 90% had issues meeting demand, with the primary problems being shortages of raw materials, packaging and staff, as well as distribution delays. Fewer of the small producers reported issues, but their problems fell into the same categories. Financial difficulties were cited more often among small producers.

- Nearly 30% of producers took advantage of the government’s Payroll Protection Plan.

- This year appears to continue or build on the sales levels achieved in 2020 for most producers. Nearly 40% report first quarter 2021 sales at the same level as last year, and nearly 50% reported further increases. And producers are optimistic about continuing these trends, with a mere 5% anticipating sales declines.

- Most (nearly two-thirds) of responding producers did not participate in tradeshows and conferences, and therefore felt no business impact from show cancellations in 2020.

- The producers that did participate in events favored the Natural Products Expos, Fancy Food Shows and IFT Show. While some felt that they lost short-terms sales and their future growth was hurt by the shows being cancelled, nearly 30% noted that they saved money and time by not attending. Some of those savings were reinvested in increased marketing, DTC sales and virtual events.

- Interestingly, half of the producers plan to continue their involvement as events resume at the same level as before the pandemic, and fully one-third plan to increase activity.

- Looking ahead, producers see numerous challenges on the horizon, led by a need for expanded distribution. They expect many of the recent shortages to continue to challenge, compounded by production, facility and financial constraints. While Covid protocols and food safety concerns persist, they are joined by the need for product development, e-commerce skills, and consumer marketing

- The clearly-articulated top priority for producers is a better-educated consumer. When asked what would foster increased consumption of fermented foods and beverages, the top item for nearly 70% is consumer education as to the nature and benefits of fermentation. The next highest priorities all support this same goal — more research into health impact (+40%), greater familiarity with flavors of fermentation (+40%) and more exposure at retail (+30%).

SCIENCE, HEALTH & RESEARCH

- The bulk — nearly 75% — of these respondents work in an academic environment, with very small clusters in government and medical/health organizations. It’s a well-educated group, with over half holding doctorates, plus another quarter with Master’s degrees. Roles are split quite evenly into thirds — professors, science/technical support and students/postdocs.

- Over 60% of these respondents are looking into connections between fermentation and health; roughly half are specifically focused on gut health and the human microbiome. Overall, three-quarters are currently researching fermentation and fermented products. Their activities, though, span the full spectrum of product categories. All the key categories among our producers — Sauerkraut/Kimchi, Pickles, Condiments/Sauces, Kombucha and Kefir — were well-represented in research. But they were joined by meaningful work across the board — Yogurt, Beer, Cheese, Alternative Proteins, Koji, Wine, Sourdough, Tempeh, Tea — even Natto!

- Slightly more than a third of this group is involved with fermented alternative proteins – an important, emerging category.

- Funding for research showed more declines (30% of respondents) than gains (under 15%) over the last year. But half of our sample expects funding to increase in the coming 12-18 month.

- Our Science, Health & Research respondents were split in how they viewed the interest in fermentation research — 60% felt the focus was increasing, but the topic was not yet a top priority. Yet a third saw fermentation as a hot topic, with more emphasis and activity than ever.

- Respondents in this group shared the views of producers that the key activities that would drive increased consumption of fermented products are:

- Consumer education about fermentation

- More research into health benefits

- Greater consumer familiarity with fermented flavors

- Published in Business, Food & Flavor, Health, Science

Does New FDA Yogurt Standard Fall Short?

Forty years after the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) released its first legal definition of yogurt, the government agency has now updated that standard of identity. But, according to the International Dairy Foods Association (IDFA), this new final rule is so outdated and out-of-touch with yogurt makers that popular products could be removed from grocery store shelves. The IDFA, which represents the nation’s dairy manufacturing industry, submitted an 87-page formal objection to the FDA.

“The result is a yogurt standard that is woefully behind the times and doesn’t match the reality of today’s food processing environment or the expectations of consumers,” says Dr. Joseph Scimeca, senior vice president of IDFA’s Regulatory and Scientific Affairs.

The IDFA is particularly concerned that the FDA crafted its final rule using comments made when the agency first pitched the guideline 12 years ago. Scimeca continues: “the final rule is already out of date before it takes effect…as if technology has not progressed or as if the yogurt making process itself has been trapped in amber like a prehistoric fossil.”

The revised standard does not include IDFA’s recommended revisions.

Read more (IDFA)

- Published in Business

Redzepi: We Need Restaurants to “Feel Alive”

Restaurants have been under tremendous economic pressure, suffering from business losses during the Covid-19 pandemic. And there’s now a staffing shortage, as long hours and low pay have driven many away from the industry.

Bloomberg columnist Bobby Ghosh explored how restaurant dining may change in an Instagram live interview with Rene Redzepi, owner and co-owner of Noma, Copenhagen’s two-Michelin star restaurant world-renowned for its experimental fermentation lab. Pandemic restrictions shut down Noma twice, forcing Redzepi to create additional revenue streams outside the traditional dining room.

In the summer of 2020, Noma opened an outdoor, walk-in burger and wine bar. Earlier this month, they announced Noma Projects, a direct-to-consumer line that will initially sell garums.

Below are highlights from Ghosh’s interview with Redzepi.

Ghosh: What did you learn about how people were feeling about returning to restaurants?

Redzepi: Restaurants, you don’t need them to stay alive but you need them to feel alive. That was very, very clear, that people were ready to go out. You know they say it’s the catch-up effect, and that definitely happened here in Copenhagen. People were everywhere, they were in piles to get a bite to sit down, have a glass of wine and meet other people.

Ghosh: When you began to think about reopening the proper dining space and planning your menu for the reopening, did you have any particular thoughts or concerns about whether people’s habits in restaurant dining might have changed in the course of the year that they were all locked up?

Redzepi: Yeah, so we went through the first lockdown, opened up, we were open for about five months and then it all came back and we had to close (again during the second lockdown). On the second lockdown, we were shut for six months and, in that time, we were very worried about everything, I mean we still are, but I guess we’re a little less worried now than before because we’re finally open again. We did think “Would people even sit for hours in a restaurant? What is it that everyone wants?” Besides that, people in Denmark, they started really cooking at home again. Takeaway offerings had become quite common, even from some of the best restaurants, something that would be considered completely impossible five years ago. If you had takeaway as a fine dining establishment, you sort of sold out in a way and that was starting to happen.

But I decided with myself, and that was a personal decision, is that in my life I need this creativity, I need to have guests, I need to work on a menu on a daily basis, so during the lockdown I went to work every day in the kitchen as if we were going to open the following day. We actually made two full menus and one of them will never be served because we ended up being closed throughout it. And then we said “OK, let’s just open up and see what happens, will people still want to come out?” and we opened up our reservations knowing that we would cater only to 100% local crowd and it’s gone really well, really really well.

Ghosh: The thrill of being in a nice restaurant and being able to talk to people and enjoy a meal is incomparable um and I do appreciate the value of fun after the year and a half that we’ve all had. Can you give us an example of a dish that you have in your menu now that reflects this attitude of fun, the surprise.

Redzepi: Swedish saffron believe it or not, it’s really, really strong and tastes amazing. We make this fudge with it and we found out that you can actually use the sort of the cutting of walnut as a wig for candles because the oil content in the walnut makes it flammable. And so we basically shaped or molded this little toffee into a candle. It sounds complicated but it’s quite easy to do when it’s hot and then we put this walnut light into it and it comes to the table when they’re drinking coffee and people think it’s you know for coziness and then as it burns out people are then instructed to eat it that’s a that’s a moment where that’s fun you know it’s creativity, it’s delicious it surprises people and it just really makes it makes a difference to people you can feel that they’ve been needing something like that.

Ghosh: What have you learned that you didn’t already know about restaurant economics over the past year that now factors in your thinking about what Noma is and what Noma needs to be in the future.

Redzepi: Oh man, you’re hitting something that we’ve been talking about for the past two years because, particularly in the last year-and-a-half, restaurant economics, they’re terrible. We’ve had 18 years of operation and we’ve had an average profit of 3%. It’s just enough to keep us running and keep painting the house, so during this pandemic we did think to ourselves “Are we going to continue like this for another 18 years, where we don’t have any money to change anything, even if we want it?” You know we’re going to have to find different ways of operating so that we can have a different economics in it. We have to figure out a way if we want to be here for another 18 years because you know it won’t continue like this. So we have definitely thought of many many things and recently we launched this thing that we call Noma Projects. Noma Projects is a sort of a platform to launch a myriad of things, it’s a for-profit company, but we only want to attack projects that also connect to some sort of a worldly issue, and the first project one is is a vegan and a vegetarian garum sauce that you use as a flavoring to add umami to your vegetarian and vegan cooking. It’s a way to help people eat more vegetarian so that’s project one, that’s something that we worked on almost almost since the first lockdown that happened to us we were like we need to step into this.

Ghosh: About six months ago, I did a piece about restaurant economics and the pandemic. I talked to your friend David Chang of Momofuku. We’re saying that we have to figure out more ways to find revenues outside of the dining room. You know, can we get 50% of the revenue from outside of the dining room where the margins are larger to sustain, to underwrite the amazing creativity that goes on in your kitchens? Is that possible? Have consumer tastes or consumer behaviors now changed in a way that will allow that kind of thing?

Redzepi: I think what happened during the pandemic is that it’s been considered more OK for restaurants of say Momofuku caliber or Noma to actually think of ways to put better economics into the system. That has opened a new door and for us, we’re grabbing that opportunity, we need to, definitely. Our industry needs to, in general. It’s an industry that’s under copious amounts of pressure, we deal with poor profit margins, low incomes, people are overworked, they’re underpaid, there’s bad management and a lot of it is a result of there’s simply no money in the industry, people can’t afford to do maneuver any new way they want, and we don’t have any business training either. It’s very interesting what’s going on. I think a lot of creativity is going to come out of restaurants in the next couple of years.

Ghosh: Now in addition to being a chef, you’re a thinker in your line of work. Through MAD Academy, which used to be anyway your annual gathering of of great chefs from around the world, you’ve spent a lot of time thinking about your industry and the future of your industry. I imagine that during the course of the past year, year-and-a-half you’ve had many conversations with the kinds of people who would previously have come to that conference. What are some of the common themes, the common challenges for fine dining establishments?

Redzepi: I think in food in general, the most common problem, and I think it’s going to continue for a while, is that there’s a gigantic staff shortage right now. I think in the pandemic, a lot of people have had an opportunity to rethink their life and say “OK, am I in this industry for the next 20 years or is this a moment for me now to start studying or become a farmer or something else.” That is really the biggest issue that we have right now, there’s no question in my mind. This is something that at MAD we’ve been discussing for almost a decade. If we’re not able to help transform (and this includes myself by the way I’ve spoken about this many times) this gigantic lack of leadership that we face as an industry where we have a poor ability to actually just manage ourselves, manage our restaurants and be supportive of people, that will be the first step that needs to happen which is slowly happening. But then providing better pay and better work hours, that are related to economics. I see our industry being far from that, unless we figure out a way to either charge more that there’s more value towards foods and people that work in the industry or we find other revenue streams. Those are the big, big questions that we are dealing with at MAD. At Noma, I deal with this as a employer myself, how to actually be an inspiration, but how to also provide for staff that are having children, and how can we have everyone stay here for 40 years in this industry? That’s really hard questions.

- Published in Business

Noma Goes DTC

Noma is coming into the home kitchen.

The fermentation-focused restaurant, lauded as one of the top restaurants in the world, is selling its first line of packaged products. Two garums — vegan Smoked Mushroom and vegetarian Sweet Rice and Egg — will soon be available to ship internationally through the brand’s website, Noma Projects.

“It’s a space for us to channel our knowledge, our craft and experimentation into a new endeavor,” says René Redzepi, chef and co-owner of the Copenhagen-based restaurant.

Redzepi shared details of the launch in a video on the site. Noma Projects will include pantry products and community-based initiatives, “a way for us to address issues we care about through the lens of food.”

Noma’s Pantry Staples

The garums are Noma’s “take on a 1,000-year-old recipe that we’ve been developing over the past two decades.” Redzepi says the “potent, umami-based sauces” have been the “key to our success at Noma in our vegetarian and vegan menus.

He hopes the garums will help more people cook plant-based meals, announcing in the video: “We want to help you bring more vegetables into your everyday cooking.” The garums provide the flavor of meat and fish without the animal. The website description notes: “Shifting towards a more plant-based diet is the easiest way for an individual to help the environment. We hope these garums will do the same for you that they’ve done for us, help inspire and create more delicious plant-based meals when you cook at home.”

These products were developed in Noma’s Fermentation Lab, where dozens of pantry staples were tested before landing on the garums. A garum is the “concentrated essence of its main ingredient” with a strong umami flavor, and Redzepi describes it to the WSJ. Magazine (the luxury magazine published by Wall Street Journal): “It has the potency of a soy sauce, except it tastes of what it is.” Both are brewed with koji rice, what Redzepi calls the “mother fungus.”

The garums are currently fermenting and will be ready for shipping in the fall or winter. The expected price point is $20-$35 for a bottle.

And more garums are in the works. Noma Fermentation Lab director, Jason Ignacio White, says a roasted chicken wing garum is next.

“It tastes like super chicken stock with umami,” White tells WSJ. Magazine, ”so it’s a familiar flavor, but there’s something about it that you can’t really put your finger on, that makes your tongue dance.”

Improving Profitability

Despite Noma’s expensive tabs — the 20-course tasting menu costs 2,800 Danish kroner (or around $447), and the wine pairing is another 1,800 Danish kroner (or around $287) — in the 18 years since it opened, the restaurant has hovered at only a 3% profit margin. Redzepi hopes Noma Projects will make more money. While it is “a family-run garage project,” its goal is to reach a million customers.

Like many restaurants around the world, Noma shut down during the pandemic. They reopened as a burger and wine bar in June 2020, and the walk-up, outdoor dining experience was such a success that it became a permanent restaurant, POPL.

Noma resumed regular operations on June 1, 2021. The pandemic closure allowed Redzepi and his team to finally tackle the retail brand, something he said they had debated for years.

- Published in Business, Food & Flavor

Picturing Traditional Sake

Hoping to spur interest in traditional sake, a Japanese producer has published a picture book What is Sake? that takes readers on a tour of their sake facility. Suigei Brewing Co., based in the western city of Kochi, uses the book to detail how sake is made. The bilingual book includes English translations.

The president of Suigei Brewing Co., Hirokuni Okura, notes Japan’s sake culture is gradually being forgotten. He said he desires to “have both adults and children view sake, an element of Japanese food culture, as something close to them.”

The book’s illustrator, Misae Nagai, featured all 53 employees of Suigei in her charming illustrations.

Read more (The Mainichi)

- Published in Business, Food & Flavor

Best Practices for Cash Flow Management

Running a food or drink business is challenging in today’s market — there’s increasing competition, fast-paced trends and challenging access to retailers. If you run a fermentation-based business with a long production cycle, those market forces are compounded.

“A lot of businesses in this sector are in it because of the passion, they love what they’re doing, and sometimes the finances can feel very mysterious, there’s an aversion to dealing with it, and they aren’t taking the time to really look and understand the numbers,” says Maria Pearman, a principal with Perkins & Co., Portland, OR-based professionals in food and beverage finance and accounting. She shared her expertise during a TFA webinar, Best Practices for Cash Flow Management.

“Cash flow forecasting, it’s not rocket science. It’s not hard stuff. It is just very foreign to a lot of people and they avoid it,” Pearman says.

Matt Hately, a TFA Advisory Board member who moderated the webinar, agreed. Hately is an investor and advisor in fermented food and beverage brands.

“Managing cash…I would argue that it’s even more of a challenge for fermentation companies where your production cycles aren’t instant, they might take a week or three weeks or six weeks and, when you’re starting, your suppliers are probably demanding to be paid up front, your customers want 30-day terms,” he says .

Fermented Financials

Pearman, author of the book Small Brewery Finance, shared an overview on cash management. Fermentation businesses need to closely manage their cash conversion cycle as production cycles lengthen. The cash flow conversion cycle is the period between when money is spent to purchase ingredients to when payment is received from the sale of the final product.

Fermented products — which can take anywhere from a few weeks to even years to ferment — have a long cycle.

Pearman shared the example of a whisky distiller. After fermentation, whisky ages in barrels for years. All the while — before the product is ever sold — there are ongoing overhead costs for the distillery, like rent, utilities and staff.

“The rhythm of your cash flow is not going to match the rhythm of your income, and cash flow management is about bridging that gap,” Pearman says.

Cash Flow Forecasting

There are three primary financial reports that make up a business’ financial statements:

- Balance sheet (snapshot of the status of a company at a moment in time)

- Income statement (performance over a period of time)

- Statements of cash flows (sources and uses of cash over a period of time)

Often overlooked is cash flow forecasting, the expected inflow and outflow of cash over future periods.

The cash flow forecast, Pearman notes, is not standard in business financial records. It is usually kept outside of an accounting system as it’s information management generally uses. It’s important because a business can’t rely on just their income statement or bank balance to manage cash flow — labor, overhead and cost of inventory must be part of the expenses. She compared managing cash without a cash flow forecast to “building a house without a hammer.”

“One of the biggest pitfalls that I see with businesses is chasing profitability instead of cash flow,” Pearman says. “It is completely understandable because we’re all hardwired to try to do things as efficiently as we can, get the best deal, but truly in the early stages of a company, it’s way more important to manage cash flow than profitability.”

“It’s a high cost for bringing a new product to market. Cash flow issues are going to be prevalent regardless of where you are in your life cycle, and the best way to guard against cash issues is to have a cash flow forecast.”

During the webinar, Pearman shared a detailed look at a sample business’ financial workbook. She noted that it seems arduous to manage that level of detail but, without it, “you’re really flying blind.”

“It will force you to be highly in tune with the rhythms of your business,” she continues. “It will force you to learn it at such a level that it starts to become innate knowledge, you know it like the back of your hand and there’s no shortcut to that.”

View Pearman’s video presentation, companion presentation and companion spreadsheet.

- Published in Business

Dunkin’ Kombucha

Move over, Dunkin’ Coffee. The chain known for its coffee and donuts is branding itself into new territory — kombucha. Dunkin’ is the first chain restaurant (to TFA’s knowledge) to make their own kombucha. They are testing their new Dunkin’ Kombucha — made in two flavors, Fuji Apple Berry and Blueberry Lemon — in select restaurants in the Albany, N.Y., and Charlotte, N.C., markets.

According to their release, “Dunkin’ continues to democratize delicious by testing kombucha for the first time.” In any case, this test is further evidence of the fermented tea’s increased popularity as an alternative to soda.

Read more (Dunkin’)

- Published in Business

Sake Brewers Suffer in Japan

As Covid-19 restrictions are lifted, American sake breweries are opening their doors to customers again. But across the world in Japan, where sake originated, many izakaya or sake pubs remain closed. Japanese brewers expect sales to slump for a second year in a row because of the pandemic.

“This right now might be the most challenging time for the industry,” says Yuichiro Tanaka, president of Rihaku Sake Brewing. “There’s nothing much we can do about that. In our company, we’re trying to become more efficient and streamline our processes so that once the world economy returns to what it formerly was, we’ll be able to much more efficiently fill orders.”

Tanaka, Miho Imada (president and head brewer of Imada Sake Brewing) and Brian Polen (co-founder and president of Brooklyn Kura) spoke in an online panel discussion Brewers Share Their Insider Stories, part of the Japan Society’s annual sake event. John Gauntner, a sake expert and educator, moderated the discussion and translated for Tanaka and Imada, who both gave their remarks in Japanese. (Pictured from left to right: Gautner, Tanaka, Imada and Polen.)

Recovery Struggles

Japan — which has been slow to vaccinate (only 9% of the population has been fully vaccinated, compared to 47% in the United States) — is currently in a third state of emergency. In the country’s large cities, no alcohol can be served in restaurants. “This is just devastating to the industry,” says Gaunter.

Though sake pubs in smaller metropolitan areas and countryside regions are allowed to be open, few people are out drinking. Many pubs have closed, and others refuse entry to anyone from outside of their prefecture.

“Sales of sake are very seriously affected,” says Imada, one of few female tôji or master brewers. “Rice farmers that grow sake rice are seriously affected as well. If brewers can’t sell sake, they have no empty tanks in which to make sake, so they don’t order any rice and the effects are transmitted down to rice farmers.”

Sake rice is more challenging to grow than table rice because the rice grains must be longer. The amount of sake rice planted in Hiroshima — where Imada Sake Brewing is based — is down 30-40%. Farmers may give up growing sake rice and switch to table rice for good.

The effects of Covid-19 on Japan’s sake brewers will linger into the fall when the next brewing season starts again.

“We cannot really expect a recovery in the amount of sake produced next season, and so therefore production will drop for two years in a row,” she says.

Premium sake brewers with rich generational historys — like Imada Sake Brewing and Rihaku Sake Brewing — are struggling to sell their high-end products.. Department store in-store tastings — a boon to premium sake brewers — have disappeared.

Adapting to Covid

In New York, as pandemic recovery efforts continue, Polen has seen the pent-up demand from consumers. Brooklyn Kura’s retail, on-premise and taproom sales are increasing. After scaling back production and their team in 2020, Brooklyn Kura is now hiring again.

“More importantly, and I think the silver lining out of this, we really needed to redouble our efforts to create a direct line of communication with our best customers,” Polen says.

During the pandemic, Brooklyn Kura launched both a direct-to-consumer business and a subscription service featuring limited-run sakes. “That’s helped us on our road to recovery.”

Imada Sake, too, found ways to improve business. They’re selling bottles and hosting tasting events through their website.

“One of the principles of the Hiroshima Tôji Guild [guild of master sake brewers], the expression is ‘Try 100 things and try them 1,000 times.’ Or in other words the point is keep trying new things and see what contributes towards improvement,” Imada says. “These words convey the spirit of using skill and technique or technology to get beyond difficulties.”

Imada Sake exports 20% of its production; as more countries recover, exports continue to grow. Direct-to-consumer sales, she says, vary and are only constant around Christmas.

Rihaku Sake sells much of their sake to distributors and is seeing international exports increase. They also began direct-to-consumer internet sales, but that channel “didn’t grow as much as I was hoping.”

Consumer Education

France and Italy export billions of dollars of wine a year. Polen argues that sake could be an equally profitable export for Japan. Education and exposure, he says, are the challenge.

“In craft beer and fine wine, a lot of those initial encounters with those products come in places like the tap room in Brooklyn or the wineries in California or the local craft brewery, so creating more of those connection points and initial introduction points in a market like the U.S., having a better facility to distribute sake across the U.S., will help to expand the market, not just to domestic producers but also for the storied producers of Japan as well,” Polen says.

Sake is the national beverage of Japan, and strict brewing laws strive to keep it pure. Japanese sake can only be made with koji and steamed rice. Add hops to it and the drink cannot be called sake legally anymore.

Many sake tôji in Japan are running a multi-generational family brewery.“These craftsmen, who have been brewing sake since they were young, have decades of experience to develop what we call keiken to chokkan or experience and intuition,” Tanaka says, adding that Japan is the only place to buy certain industrial-sized sake making machines such as steamers and pressers. “There’s a lot of advantages that breweries in Japan have. If brewers overseas get too good, this might actually cause problems for brewers in Japan. However, more important than that, I think it’s important for all of us to continue to study how to make better and better sake so everyone around the world can enjoy it.”

Rihaku tries to make their sake recognizable to local consumers who are unfamiliar with the rice wine. Their Junmai Ginjo sake has the nickname “Wandering Poet,” a reference to the famous poet Li Po. Legend says Li Po drank a bottle of sake then wrote 1,000 poems.

“We think a lot about how to get more people that are non-Japanese and outside of the Japanese context excited about sake making and excited about the sake we make,” Polen says. “That includes those folks that are passionate fermenters, like the beer community, that really want to know and learn about things like spontaneous fermentation. So (sake) styles, like yamahai and kimoto, are very easy transition points, very easy talking points for us with that community of brewers and consumers that are really excited to drill deeper into fermentation, especially natural fermentation.”

- Published in Business

Fermentation for Alternative Proteins

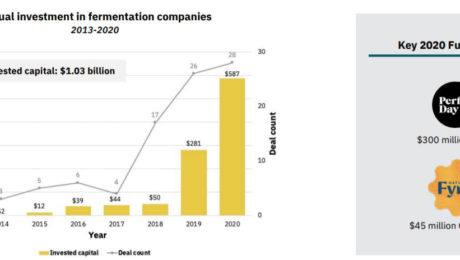

Investments in alternative protein hit their highest level in 2020: $3.1 billion, double the amount invested from 2010-2019. Over $1 billion of that was in fermentation-powered protein alternatives.

It’s a time of huge growth for the industry — the alternative protein market is projected to reach $290 billion by 2035 — but it represents only a tiny segment of the larger meat and dairy industries.

Approximately 350 million metric tons of meat are produced globally every year. For reference, that’s about 1 million Volkswagen Beetles of meat a day. Meat consumption is expected to increase to 500 million metric tons by 2050 — but alternative proteins are expected to account for just 1 million.

“The world has a very large demand for meat and that meat demand is expected to go up,” says Zak Weston, foodservice and supply chain manager for the Good Food Institute (GFI). Weston shared details on fermented alternative proteins during the GFI presentation The State of the Industry: Fermentation for Alternative Proteins. “We think the solution lies in creating alternatives that are competitive with animal-based meat and dairy.”

Why is Alternative Protein Growing?

Animal meat is environmentally inefficient. It requires significant resources, from the amount of agricultural land needed to raise animals, to the fertilizers, pesticides and hormones used for feed, to the carbon emissions from the animals.

Globally, 83% of agricultural land is used to produce animal-based meat, dairy or eggs. Two-thirds of the global supply of protein comes from traditional animal protein.

The caloric conversion ratios — the calories it takes to grow an animal versus the calories that the animal provides when consumed — is extremely unbalanced. It takes 8 calories in to get 1 calorie out of a chicken, 11 calories to get 1 calorie out of a pig and 34 calories to get 1 calorie out of a cow. Alternative protein sources, on the other hand, have an average of a 1:1 calorie conversion. It takes years to grow animals but only hours to grow microbes.

“This is the underlying weakness in the animal protein system that leads to a lot of the negative externalities that we focus on and really need to be solved as part of our protein system,” Weston says. “We have to ameliorate these effects, we have to find ways to mitigate these risks and avoid some of these negative externalities associated with the way in which we currently produce industrialized animal proteins.”

What are Fermented Alternative Proteins?

Alternative proteins are either plant-based and fermented using microbes or cultivated directly from animal cells. Fermented proteins are made using one of three production types: traditional fermentation, biomass fermentation or precision fermentation.

“Fermentation is something familiar to most of us, it’s been used for thousands and thousands of years across a wide variety of cultures for a wide variety of foods,” Weston says, citing foods like cheese, bread, beer, wine and kimchi. “That indeed is one of the benefits for this technology, it’s relatively familiar and well known to a lot of different consumers globally.”

- Traditional fermentation refers to the ancient practice of using microbes in food. To make protein alternatives, this process uses “live microorganisms to modulate and process plant-derived ingredients.” Examples are fermenting soybeans for tempeh or Miyoko’s Creamery using lactic acid bacteria to make cheese.

- Biomass fermentation involves growing naturally occurring, protein-dense, fast-growing organisms. Microorganisms like algae or fungi are often used. For example, Nature’s Fynd and Quorn …mycelium-based steak.

- Precision fermentation uses microbial hosts as “cell factories” to produce specific ingredients. It is a type of biology that allows DNA sequences from a mammal to create alternative proteins. Examples are the heme protein in an Impossible Foods’ burger or the whey protein in Perfect Day’s vegan dairy products.

Despite fermentation’s roots in ancient food processing traditions, using it to create alternative proteins is a relatively new activity. About 80% of the new companies in the fermented alternative protein space have formed since 2015. New startups have focused on precision fermentation (45%) and biomass fermentation (41%). Traditional fermentation accounts for a smaller piece of the category (14%). There were more than 260 investors in the category in 2020 alone.

“It’s really coming onto the radar for a lot of folks in the food and beverage industry and within the alternative protein industry in a very big way, particularly over the past couple of years,” Weston says. “This is an area that the industry is paying attention too. They’re starting to modify working some of its products that have traditionally maybe been focused on dairy animal-based dairy substrates to work with plant protein substrates.”

Can Alternative Protein Help the Food System?

Fermentation has been so appealing, he adds, because “it’s a mature technology that’s been proven at different scales. It’s maybe different microbes or different processes, but there’s a proof of concept that gives us a reason to think that that there’s a lot of hope for this to be a viable technology that makes economic sense.”

GFI predicts more companies will experiment with a hybrid approach to fermented alternative proteins, using different production methods.

Though plant-based is still the more popular alternative protein source, plant-based meat has some barriers that fermentation resolves. Plant-based meat products can be dry, lacking the juiciness of meat; the flavor can be bean-like and leave an unpleasant aftertaste; and the texture can be off, either too compact or too mushy.

Fermented alternative proteins, though, have been more successful at mimicking a meat-like texture and imparting a robust flavor profile. Weston says taste, price, accessibility and convenience all drive consumer behavior — and fermented alternative proteins deliver in these regards.

And, compared to animal meat, alternative proteins are customizable and easily controlled from start to finish. Though the category is still in its early days, Weston sees improvements coming quickly in nutritional profiles, sensory attributes, shelf life, food safety and price points coming quickly.

“What excites us about the category is that we’ve seen a very strong consumer response, in spite of the fact that this is a very novel category for a lot of consumers,” Weston says. “We are fundamentally reassembling meat and dairy products from the ground up.”

- Published in Business, Food & Flavor, Health, Science

Fermented Skincare?

Is the future of skincare products fermented? A Finnish company is tapping into consumer trends they believe “will become the norm in five to ten years.” Brand Circulove is natural, sustainable, holistic — and made with fermented ingredients. Ingredients are fermented for 3-5 weeks, then food-grade oils are added.

“It’s an old tradition built in[to] this new technology,” says Paivi Paltola, Circulove CEO and co-founder. “It’s also this kind of more holistic way of thinking because fermentation helps your skin renew itself.”

Paltola says consumers are familiar with fermented ingredients in foods and beverages, but more education is needed to help them understand their role in beauty and skincare products.

Read more (Cosmetics Design)

- Published in Business