Wineries Pivot Without Tasting Rooms

When Black Fire Winery in Michigan began struggling through the pandemic, owner Michael Wells (pictured) had to pivot from a tasting room. “I’ve had to rethink the way I have been doing things. My original business model was to sell out of the tasting room, but now I’m looking to make a huge presence online and outside the tasting room.”

Wells, the first Black owner of a commercial winery in Michigan (and believed to be the only Black commercial winemaker in the state), now sells online in 38 states and is looking to can his beer and hard cider (currently only available in his tasting room). Winemaking is a second career for Wells. He began as a home winemaker, experimenting after coming home from his job with the local fire department. After he retired, he opened Black Fire Winery and now tends to 11 acres of wine grapes.

Read more (Detroit News)

- Published in Business

Wildfires Cost California Wineries Billions

Devastating recent wildfires need to spur the California wine industry to invest in researching ways to mitigate the effects of fire and smoke damage. The California Wine Institute partnered with firm BW166 to calculate the cost of the 2020 wildfires to wineries; a $3.7 billion estimate includes loss of property, wine inventory, grapes and future sales.

“At a time of year when vintners would typically be throwing harvest parties and stomping grapes, they were instead faced with mounting uncertainty about the viability of their crop. Many of them decided not to make some or all of the wine that they’d planned to bottle because of the smoke damage. Months later, wineries are still deliberating over those decisions,” writes the San Francisco Chronicle.

Read more (San Francisco Chronicle)

- Published in Business

7 Takeaways for Cideries in 2021

Despite a year when cideries around the world were forced to close down taprooms and cancel restaurant sales due to the pandemic, cider sales grew 9% in 2020.

“I know some of you are barely hanging on — but you are hanging on,” said Michelle McGrath, executive director of the American Cider Association (ACA). “We did not waver, we held our shares and we kept growing.”

McGrath presented industry statistics at CiderCon 2021, the ACA’s annual global cider conference. Because of the ongoing coronavirus pandemic, the conference was virtual this year. Nearly 800 people from 18 countries and 41 states attended the three-day conference.

Smaller, local cider brands sparked consumer interest in 2020. Sales of regional cider brands grew 33%, while national brands declined 6%.

The impact of the pandemic, though, has been severe on certain sectors of the industry. On-premise cider sales (in restaurants, breweries and taprooms) declined nearly 70% from 2019.

“We’re resilient, we’re tough, we’re savvy. You couldn’t have predicted how your business would have stood up to a once-in-a-lifetime pandemic,” said Anna Nadasdy, director of customer success at Fintech, a data company for the alcohol industry.

Nadasdy’s keynote on expected consumer trends in 2021 cited the key drivers influencing consumer behavior — the economy, politics and natural disasters. Here are seven of her takeaways for cideries:

- Consumers Buying all Alcohol Types

Though consumers have long been loyal to one type of alcohol — beer, wine or spirits — the “beer guy or wine gal” label is disappearing. Over one-third of consumers are purchasing from all three major categories.

Hard seltzer is the third largest beer segment (16% of dollar share, behind domestic premium and imported beers), but it’s the fastest growing. This is exciting for cider makers, Nadasdy notes — hard seltzer in 2018 was the size of the cider market today.

- Fruit-Flavored Cider is Growing

Though apple cider still dominates the cider market with 52% of sales, fruit-flavored cider grew three points in the past year to 12% of sales. The top three fruit-flavored products are: Ace Pineapple Craft Cider, Incline Scout Hopped Marionberry Cider and 2 Towns Ciderhouse Pacific Pineapple Cider.

(Other products in the cider category include: mixed flavors, dry cider, seasonal cider/perry, herb/spice cider.)

- Cider is Making Waves in Craft Beer

Cider — tracked as part of the overall craft beer category — is proving a worthy participant.Cider has 11% of the dollar share, second only to the category leader, India Pale Ale (41% of the market).

“That’s really impressive for such a small base,” Nadasdy says. “Even though you guys are a smaller segment, you still have a lot to contribute to the overall beer category. And I think it’s important when you’re having these conversations with retailers that you are able to point out these wins.”

- Hard Kombucha is Gaining Ground

Cideries are competing with hard kombucha. Though hard kombucha is a fermented tea and not a cider, retailers consider hard kombucha and cider comparable drinks. And hard kombucha sales are growing quickly.

“Although small now, keep an eye on (hard) kombucha,” Nadasdy said.

- Prepare for Changed On-Premise Sales

Once wide-spread vaccination is in place and on-premise dining returns, expect fundamental changes such as more online ordering, healthier menu choices and a rise in food tech like tablet menus. The National Restaurant Association listed other significant changes that will impact cideries:

- Streamlined menus. There will be fewer menu items, with 63% of fine dining operators and half of casual and family dining operators saying they will reduce their offerings.

- Alcohol-to-go. Seven in 10 full-service restaurants added alcohol-to-go during the pandemic. Thirty-five percent of customers say they are more likely to choose a restaurant that offers alcoholic beverages to-go.

- Rosé-Flavored Cider is Out

Every brand of rosé-flavored cider is losing sales. The top three brands showing the most significant losses in this category are: Angry Orchard, Bold Rock and Virtue.

- Cans Are King

Cans are leading the dollar share of the market, growing at 1.5 times the rate of bottles. Six-pack (11-13 ounce) cans are now the top share item with 29% of total cider sales. This is followed by six-pack (11-13 ounce) bottles and 4-pack (18-ounce) cans. (These figures do remove shares of Angry Orchard, which sells in bottles. Because Angry Orchard dominates 40% of the cider market, they skew the data.)

- Published in Business, Food & Flavor

Launching a Fermented Brand

One of the biggest hurdles in the food and beverage industry is getting a product to market — an even bigger challenge for fermented food and drink brands featuring live bacteria.

“Fermented foods in general are still relatively new in the commercial marketplace. When we started, most beer distributors knew nothing about it. And that’s still a big challenge, how to communicate what you have. What is a fermented food? Why should people care about it?” says Joshua Rood, co-founder and CEO of Dr Hops Real Hard Kombucha. Rood shared his advice during a TFA webinar, Launching a Fermented Brand.

Rood officially began Dr Hops in 2015 with co-founder Tommy Weaver. They met in a yoga class, and turned their passion for health and great hops into a kombucha beer they started brewing in Rood’s kitchen.

At the time, there was a lot of variety and craft beer and kombucha, but hard kombucha was unheard of. “You don’t have a lot of focus on health in alcohol,” Rood says.

Rood went to investors with a pitch deck that outlined why traditional alcohol products don’t appeal to a health-conscious consumer — craft beer is made with gluten, cider is high in sugar and hard alcohol is too strong for regular use. Dr Hops, meanwhile, is gluten-free, low in sugar, unfiltered, made with organic ingredients and full of active probiotics.

“We have a passion for creating more delightful, health-conscious alcohol, and really pushing the envelope with that,” Rood says. “One of our biggest challenges is still how to communicate that into a very tiny amount of time to consumers, retailers and distributors.”

Starting in a category that didn’t yet exist, figuring out licensing took years. Dr Hops began with $13,000 raised from a Kickstarter campaign, then crowdsourced another $10,000 the following year. By 2017 — with labelling, alcohol licensing and product stability figured out — investors pledged $115,000, enough to start small-scale commercial production. Dr Hops officially went to market in 2018, self-distributing and selling at street fairs and beer festivals.

“Part of the key to selling stuff without a huge marketing budget is focus,” says Alex Lewin, webinar moderator, Dr Hops advisor and TFA Advisory Board member. “Dr Hops started in the Bay Area, and won over relationships we had with some retailers — we had some real advocates. Don’t do a national launch if you have no budget.”

Rood stresses education is a key piece of marketing for the fermentation category.

“How much is the whole community speaking about and educating the world about and celebrating the value of live fermented foods? The more we’re all doing that, the more it works to sell these products,” he adds.

Test audiences, consumer feedback and word-of-mouth marketing have been key to Dr Hops success.

“The fact that we were able to grow our business almost three times in 2020 even in the pandemic with no marketing is one of the best things we have to say about what we have. People want this,” Rood says.

Highlighting strengths helps Dr Hops distinguish itself in a newly-competitive field of hard kombucha brands. Dr Hops’ product line includes flavors that compare to well-known alcohol beverages. Their Kombucha Rose flavor is a substitute for wine, Ginger Lime for a cocktail, Kombucha IPA for beer and Strawberry Lemon for a mimosa.

“While people might not understand hard kombucha, they pretty much already have a preference between beer, wine, cocktail and champagne or spritzers,” Rood says.

Health is core to Dr Hops, but higher-alcohol drinks are also higher in calories. Seltzer has been a key competitor to hard kombucha because seltzer’s calories are low.

“But it’s not interesting,” Rood says. “If you really love alcohol or food or beverage in general, you want something more interesting than that. At this point, we’re willing to gamble on enough people who care about transparency and authenticity that if we put the nutrition label on there and list all the ingredients, even if it doesn’t compare very well on a calorie level, there’s enough else to it that people are going to try it.”

- Published in Business

Reinventing 144-year-old Miso Company

Yoko Nagatomo Shiomi, president of the fourth-generation Kanena Miso & Soy Sauce Brewery, is one of few female toji (head brewers) in the miso industry. Japanese traditions delegate that businesses are passed onto male heirs. But when Shiomi’s father suffered a debilitating stroke, she was the only heir left.

Shiomi’s great-grandparents started the miso and soy sauce brewery in 1877. Shiomi never expected to inherit the company. “I had no expertise or information, and knew it was uncommon for girls to do this type of work, however I needed to strive,” she says. Before officially taking over, Shiomi and her mother spent three years with the company’s brewers learning the intricacies of the business. Like the most effective ways to combine soybeans and barley with koji spores.

Though miso and soy sauce have long been staples in Japanese dining, Shiomi told the Japan Times she was shocked to learn how much miso consumption had declined in the average household. “Miso is a really nutrition fermented seasoning and really authentic to our tradition,” she said. She began volunteering to teach kids how to cook with miso. It also inspired her to create a new miso product easier to use for the modern shopper: dried miso packets, make-your-own miso kits, and miso-marinated cuts of pork.

Read more (Japan Times)

- Published in Business, Food & Flavor

Keeping Traditional Fermentation Alive

Britt’s Fermented Foods is one of the only pickle companies in America still using oak barrel fermentation — how pickles were first fermented in ancient Egypt. But this method is often difficult and time-consuming, and many producers abandoned it in the 1970s when food regulation laws changed.

“The oak barrel has that ability to act as an agent in the fermentation,” says owner Britt Eustis. He explained to The Seattle Times that “the tannins in the oak barrels suppress the enzyme that naturally occurs and makes pickles turn soft,” keeping Britt’s pickles crisp.

Britt’s, with a warehouse on Whidbey Island in Washington, nearly shut down in 2019 due to mounting debt and production challenges. But a blueberry farm on the island offered to partner with the company, offering financial backing and helping to diversify income streams. Britt’s now sells kimchi and sauerkraut, also fermented in oak.

Read more (Seattle Times)

- Published in Business, Food & Flavor

New Fermented Alternative Proteins

“2020 was a banner year for fermentation,” says Emma Ignaszewski at the Good Food Institute (GFI). “Fermentation is poised to solve so many challenges in the alternative protein space,” she adds. It’s scalable, low-cost and “it can produce proteins that match the taste, texture, and nutritional qualities of animal-based proteins. In some sense, it’s quite possibly the dark horse of the protein world.”

Biotech companies are using yeast engineering and fermentation technologies to cultivate new strains. GFI invested a record $435 million in fermented protein in 2020. Clara Foods makes egg white protein using fermentation. Nature’s Fynd makes a fermented protein “Fy” made from fungi in an acidic Yellowstone hot spring. Perfect Day makes plant-based, lactose-free proteins for ice cream using fermentation. Prime Roots uses koji as a protein alternative.

Ignaszewski says that meat is a category “ripe for disruption” by fermented protein.

Read more (LiveKindly)

Yogurt Sales Flat Past Two Years

The refrigerated yogurt market — $8 million at retail in 2020 — is virtually flat over the past two years. Greek yogurt — 40% of the category — is down 3%, while the small plant-based yogurt segment has grown by more than 63% over the same timeframe. – SPINS

- Published in Business, Food & Flavor

Pandemic Spurs Fermented Beverages

The coronavirus continues to drive sales of fermented drinks. Lifeway’s kefir, Farmhouse Culture’s kraut juice, Probitat’s fermented planted-based smoothies, Flying Ember’s hard kombucha and Buoy Hydration’s fermented drinks all report increased sales as consumers take a bigger interest in the immune-enhancing benefits of fermented beverages.

“As demand ramps up for immune-enhancing products, manufacturers have an opportunity to innovate with immune-supporting ingredients and flavors,” says Becca Henrickson, marketing managed of Wixon, a flavor and seasoning company. “When flavoring beverages with immune support ingredients, selecting flavors that increase or complement a product’s health perception is optimal.”

Read more (Food Business News)

New Strains Drive Probiotic Market

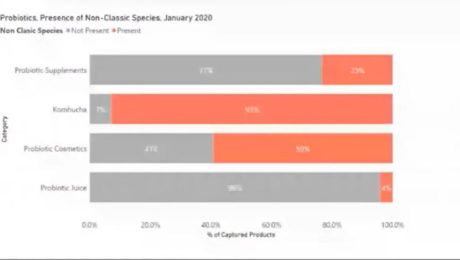

Kombucha and cosmetics are driving growth in the probiotic and prebiotic markets by making products that use non-classic strains of bacteria.

The e-commerce market for probiotic supplements was estimated at $973 million across 20 countries in 2020. America accounts for almost half of those sales. Ewa Hudson, director of insights for Lumina Intelligence, shared this info at the Probiota Americas 2020 Conference. (Lumina and Probiota Americas are parts of William Reed Business Media, the parent company for FoodNavigator.com.) The session, New Horizons for Prebiotics & Probiotics, included Lumina’s insight into non-classic bacteria strains and a panel discussion with leaders in the probiotics field.

In 2020, 32% of all probiotics in America — and 41% of the best-selling ones — contained non-classic species. Hudson said this species classification is a messy space, especially from a consumer’s perspective, because there are so many species. Kombucha includes the most non-classic probiotic species — of those products with probiotics, 93% include non-classic bacteria .

Most products with probiotics include one of the four common bacteria species: lactobacilli, bifidobacterium, bacillus and saccharomyces. Lumina excluded these four from their research to focus on the growth of the non-classic probiotic strains. These include: streptococcus thermophilus, kombucha culture, lactococcus lactis, bifida ferment lysate, enterococcus faecium, streptococcus salivarius, clostridium butyricum and streptococcus faecalis.

Though probiotics are often used in supplements, more fermented food and beverage manufacturers are using probiotic strains in their products, especially in the growing alternative protein market.

Synbiotics are also becoming more widely used; the study found synbiotics were the most prevalent formulate in probiotics. Synbiotics are a combination of both prebiotics and postbiotics. A synbiotic ensures that probiotics will have a food source in the gut.

(Probiotics are live microorganisms, friendly bacteria that provide health benefits. Probiotics can be found in fermented food and taken as supplements. Prebiotics are dietary fibers that feed the probiotics. Postbiotics are an emerging concept in the “biotics” space — postbiotics are the waste byproduct of probiotics.)

“With probiotics, we are really only starting to scratch the surface with the development of synbiotics,” says Jens Walter, PhD, professor of ecology, food and the microbiome at APC Microbiome Ireland.

The new generation of probiotics will depend on strains that are “efficacious in the gut,” Walter noted.

“If you look into the probiotic market, most of the lactobacillus species — and also species like bifidobacterium lactis — are not inherent organisms of the human gut. We’re using a lot of organisms that I would argue have an ecological disadvantage in the gut,” Walter says. “If you’re talking about next generation probiotics, I think what will become is we are looking for the key players in the gut, specifically key players that are underrepresented or linked to certain benefits, and then we are trying to put them back in the ecosystem.”

It’s challenging to find a prebiotic or postbiotic that is precise, he continues.

“Every human has a distinct microbiome. So it’s likely a synbiotic designed for one human may not be as functional in another human,” Walter says. “The opportunities here are tremendous.”

Daniel Ramon Vidal, vice president of research and development and health and wellness at the American food processing company Archer-Daniels-Midland (ADM), also spoke. He noted that the human body is made up of trillions of microbial cells, but we know little about these microbial worlds.

“There is an enormous amount of possibilities to isolate new strains that are living in our body,” Daniels says. “We need as much science as possible, that’s my message”

The panel agreed that postbiotics has become one of the next great concepts that scientists, manufacturers and gastroenterologists have latched onto. But consumers are not as familiar with postbiotics as they are with probiotics and prebiotics , notes Justin Green, PhD, director of scientific affairs for EpiCor, a postbiotic ingredient produced by Cargill.

“This causes more confusion, so I think that’s going to be another interesting aspect of postbiotics — both the identity of what postbiotics are and how it confers its benefits and (how that will be) communicated to the consumer,” Green says.