Natural & Health Labels Can be Regulatory Nightmare

Brands need to be extra vigilant over the health claims they put on their labels. A simple phrase like “Supports immunity,” “Aids respiratory health” or “Full of natural flavors” could result in a lawsuit from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), Federal Trade Commission (FTC) or a state attorney general.

“The FDA is able to set very broad and very narrow regulations in terms of what our labels can look like, what can be included in the products, what kind of claims we can make for the products, who the products can be distributed too, how they can be imported and exported and the like,” says Claudia Lewis, partner at Venable LLP, a Washington D.C.-based law firm.

Complying with these sometimes archaic laws can be challenging. The FDA, which ensures food safety, has a large jurisdictional footprint, regulating about 30 cents of every dollar Americans spend. The FTC is the authority on advertising and marketing claims for food, beverage and supplement products, and it may challenge a food brand if its marketing is deemed false, deceptive and/or misleading.

“Typically, if you’re in an FTC investigation, you’re going to have at least $300,000 in legal fees by the time you’re finished, if not over half a million dollars,” says Todd Harrison, partner at Venable. “The FTC is a very expensive regulatory agency to deal with. They can make your life pretty miserable.”

Harrison and Lewis specialize in representing functional food brands at their law firm and spoke at Expo East on the topic of Legal and Regulatory State of the Natural Products Industry. [The Fermentation Association’s virtual conference, FERMENTATION 2021 will also cover this and related topics — please check our Agenda for the latest sessions and speakers.]

Harrison and Lewis reviewed two main areas where improper labeling can get a food brand into trouble with regulators.

Using Covid-19 as a Marketing Tool

Shortly after the Covid-19 pandemic started, the FDA offered a unique relaxation of their rules and regulations for food products. Brands were challenged with supply chain disruptions and ingredient shortages. The FDA allowed temporary ingredient and formulation changes without a label overhaul, as long as the new ingredient was non-allergenic, 2% or less of the weight of the finished product, not a main or characterizing ingredient and not affecting health claims.

Though the temporary rule allows for flexibility, Harrison advises it still leaves room for litigation. Plaintiff attorneys can still sue for changes in a product’s flavor.

“Minor changes are fine from an FDA perspective, but not necessarily good from a plaintiff perspective,” he adds.

Covid-19 has also spurred a gray area in food marketing claims. Labels claiming the product prevents, treats or mitigates Covid-19 are illegal and being “aggressively pursued.”

“Anytime you mention the word coronavirus or Covid, the FDA is not going to agree with what you say because everyone will think you’re somehow implying something,” Harrison says.

Context is critical, as the agency is cracking down on any brands making health claims implying their product could prevent Covid. Brands using the phrases “immunity support” or “immune boosting” on their labels — or even on their social media pages — could be targeted by the FDA.

“The FDA has historically not liked (brands to use the term) immunity, but it was always low risk (pre-pandemic), you’d likely get a warning letter,” Harrison says. “However, in the world we live in today, the word immunity is persona non grata to the agency. Especially if you add the word respiratory on it. If you put the words ‘immunity’ and ‘respiratory’ on a label, the agency is saying ‘It’s Covid.’”

Harrison also cautions against connecting science-backed supplements and vitamins to treating a Covid infection. He uses the example of vitamin D — plentiful scientific research proves vitamin D boosts immunity, but a food brand cannot legally make that association, and doing so can set it up for litigation. Though vitamin D “is a cheap way of helping reduce your risk of (Covid-19) severity, it’s not going to keep you from getting Covid,” Harrison explains. “The way the paradigm is set up, even if you have really good science in your favor, you can’t make the claim unless you have approval by the FDA.”

“Natural” and “Health Food” Still Debatable Terms

Because there is no FDA or FTC definition of “natural,” lawsuits against brands claiming their product is natural or similar claims are prevalent. (The FDA requested public comments on the term “natural” in 2016, but no rule was issued on the policy.)

And these lawsuits don’t always come from the federal agencies. Class action lawsuits are “still alive and well,” Lewis adds. A formal definition would help protect brands because plaintiffs are filling in the holes and filing costly lawsuits. She uses the example of Welch’s Fruit Snacks, which was sued for being “more candy than fruit.”

“The plaintiffs bar has seized on that and taken these companies to task,” she says. “This wording about ‘healthy’ and this wording of ‘natural’ is also taking on a different dynamic because of consumer perception. How consumers perceive these words and how consumers’ expectations are not keeping with FDA regulations, but the plaintiff bar is using that as an opening and getting pretty good settlements in connection with consumer perception.”

Making a health inference is a slippery slope. The FDA deems a healthy food as one that suggests the product can help maintain “healthy dietary practices.” Health foods are required to be low in fat, saturated fat, cholesterol and sodium.One or more qualifying nutrients must also make up at least 10% of their weight..

For example, IZZE, makers of sparkling juices, was sued for misleading marketing because, though the drink advertised “no sugar added,” it failed to disclose it was not low in calories — a requirement under FDA regulations. Harrison takes issue with the FDA defining healthy in these confusing terms.

“I’d say it’s unconstitutional and I think I’d win that case because healthy is now low fat, low saturated food and a certain amount of macronutrients. It’s a much more complex question than that. But yet this is what plaintiff attorneys seize on,” Harrison says.

Though a new food product may be utilizing health ingredients on the cutting edge of scientific research, Harrison warns the FDA is “notoriously behind nutrition science” and brands need to be careful. He says don’t trust the government agency to keep up.

“Nutrition has evolved and continues to evolve,” he says, noting the FDA regulation to put “low fat” as a nutrient content claim just stripped fat out of food (including beneficial fat) and replaced it with simple carbohydrates. Most members of Congress “don’t know a damn thing” about health food. “We know what’s good for us. We’re not stupid people.”

How Can Brands Educate Consumers on Alt Protein?

Alternative protein companies need to stop advertising their brand as the most ethical choice and instead appeal to consumer’s taste buds.

“Sometimes plant-based food companies don’t really market themselves as food,” says Thomas Rossmeissl, head of global marketing for Eat Just, Inc., which develops plant-based “eggs” and cell-cultivated meat. “There’s this inclination to talk about mission. We say ‘We’re good for the planet,’ ‘It’s good for you,’ ‘It’s good for animals’ and obviously that’s all true and it’s admirable and it’s what drives me in our company. But it can come off like we’re sort of apologizing, that we’re negotiating with consumers, that a consumer is sacrificing something delicious to get something ethical or healthy.”

“People not buying (traditional)meat and cheese because an animal was killed or tortured. They buy because it tastes great.”

Irina Gerry concurs. Gerry is the chief marketing officer for Change Foods, an animal-free dairy brand that will launch their product in 2023. Alternative protein brands need to “flip the script from plant-based, rationalizing the food choices.” Brands need to help consumers feel that purchasing an alternative protein is a “natural choice rather than a sacrifice.”

The two spoke on a panel Insights on Consumer Perceptions of Alternative Proteins at the virtual Good Food Conference. The conference is put on by the Good Food Institute, an international nonprofit that promotes plant- and cell-based meat.

Wide Consumer Base Wanting Animal-Free

Animal-free is the main driver for customers to buy alternative products. The alternative protein industry is not just marketing to vegans, they’re also selling to flexitarians and omnivores concerned about welfare. Ninety-four percent of Eat Just consumers consume some type of animal protein.

“Sustainability is skyrocketing and potentially could cross over health as the main motivator, especially in the younger population,” Gerry says.

The modern American household family fridge is divided. There may be three types of eggs in there — conventional, cage-free and plant-based — and three types of milk — dairy milk, almond and oat. Consumers as young as 12 are the ones educating themselves on alternative proteins.

“We’re going to see this younger generation drive families to plant-based solutions,” Rossmeissl says.

Staying Honest, Maintaining Trust

Transparency will be central to public adoption. Laura Reiley, a reporter for The Washington Post who moderated the panel, noted “there hasn’t been tremendous transparency” with the alt protein market. She’s written about the market since its beginning and notes, because there’s intellectual property and so much research and development dollars, most companies have kept their food shrouded in mystery.

“We don’t want to sort of follow the example of the conventional industry. We can do better than that,” Rossmeissl says. “On the cultivated side, we have a huge responsibility to get this right. Not just as a company but as an industry, we can’t screw this up.”

Perceived unnaturalness by consumers of alt protein is a challenge. Using the term lab-grown “is disparaging to us as an industry” he continues, “but I think the best way we can address that is by being really honest and what’s in it and how it’s made.”

Gerry notes 90% of dairy cheese sold globally is made with non-animal remnants through precision fermentation — and that’s been the predominant way traditional cheese is made for over 20 years. It’s the same technology Change Food’s animal-free cheese uses.

“(These traditional cheeses) made through precision fermentation, they’re labeled under natural and oftentimes organic cheese products and nobody’s grown a third leg and nobody’s freaked out, right?” Gerry continues. “But now we’ve added one more element of that cheese — removing the cow from the cheese — and everybody seems to be greatly concerned.”

Global Kimchi Boom

South Korea’s exports of kimchi are at a record high — they have increased nearly 14% year-over-year in 2021 through August.Exports were highest to Japan ($57.2 million), U.S. ($18.9 million) and Hong Kong ($5.4 million). South Korea is expected to have a trade surplus in kimchi for the first time in 12 years.

Korea Customs Service and food industry experts attribute the rise to a few factors. First, growing consumer desire for healthier food. Second, kimchi is regularly highlighted by the media during the Covid-19 outbreak as a food that can boost immunity (note that this has not been scientifically proven). And third, “foreigners’ greater interest in Korean foods thanks to the popularity of Korean pop culture abroad.”

Read more (Korea Business Wire)

- Published in Business

The Forefront of Alt-Proteins in Africa

Price and regulation are big roadblocks for alternative proteins, an industry that is expanding rapidly, as more consumers turn to animal-free products out of concern for their health, the environment and animal welfare.

“People love meat but, at the end of the day, they’re not really attached to how it got to their plates,” says Brett Thompson, co-founder and CEO of Mzansi Meat, a cultivated meat company in South Africa. Thompson spoke at the TFA webinar The Forefront of Alt-Proteins in Africa with another leader in the South African alternative protein industry, Leah Bessa, PhD, co-founder and CSO of De Novo Dairy.

Alt-protein companies all over the world are bringing cultivated meat and dairy to consumers, but Africa as a continent has lagged.. Thompson founded Mzansi Meat Co. in 2020 and hopes to bring cell-cultured beef, chicken and braai sausages (traditional South African BBQ-style sausages) to retail shelves next year. De Novo Dairy, formed in 2021, is using precision fermentation to create milk proteins for animal-free dairy products, but without cows.

This novel biotechnology is new in South Africa, but it’s a critical element in addressing food security problems in Africa. Africans don’t consume enough food, especially protein, and as drought continues to plague the continent, raising animals for traditional meat products is becoming less and less sustainable.

“It’s a very different conversation to the rest of the world,” Thompson adds. “It’s about getting more protein into more people’s stomachs and plates.”

Big Production Costs in New Alt-Protein Space

Interest is high from investors, but scaling from pilot stage to large-scale production is challenging. Equipment is costly and labor is difficult to recruit to a new industry.

In a survey conducted by Mzansi, 50% of South Africans were willing to purchase alternative protein products — and they’d pay a higher price than for traditional meat.

“But we just got to make it available,” Thompson says. “That’s going to be the biggest hurdle for us, getting it into retail and getting it in front of people so that they can make that decision.”

Bessa says that, critical to the adoption of animal-free dairy, the consumer must receive “nature identical” products. These must replicate the taste, texture and nutrition level of traditional dairy — and precision fermentation is a “powerful tool” to helping achieve that goal.

“It’s going to be a very easy sell,” Bessa adds. “What’s really great about precision fermentation is, as a technology, it’s not limited to just one or two proteins. You can really explore other functional elements and other functional proteins across the food industry. So we’re really looking beyond just dairy, but we want to solve a big problem in the dairy industry because it’s very unsustainable.”

The Good, the Bad & the Ugly — of Government Regulation

Bessa notes regulation is a bigger challenge than technology for De Novo. Three governmental bodies in Africa oversee food production — the departments of trade, health and agriculture. Mzansi is exploring launching in food service, as an alternative to the long, arduous process of securing government approval to sell a product at retail.

“Consumers want something that’s familiar but, now with regulatory hurdles, if you have to classify and label them differently, then how familiar would that label be to consumers?” says Josephine Wee, assistant professor of food science at Penn State University (and a TFA Advisory Board member). Wee moderated the discussion with Thompson and Bessa. “I think it’s an important conversation as well because it might be confusing if it tastes just like milk but is labeled completely different.”

Transparency is a priority for both Mzansi and De Novo. Thompson says companies preaching sustainability can’t be “cagey…or you send out messages that are convoluted.” Bessa agrees, noting a young company may never recover from bad publicity over transparency issues.

“Working with new technologies, especially in food, which is such a personal thing for people, you almost want to get ahead of assumptions, you want to be the one putting out the information and the correct information,” Bessa says. “That’s why it’s so important because you’re working with a novel technology, you’re feeding people with this novel technology, and so it’s important to be transparent so that they feel comfortable and they can relate to what they’re consuming.”

- Published in Business, Food & Flavor

Natural & Organic Sales Growing but Slowing

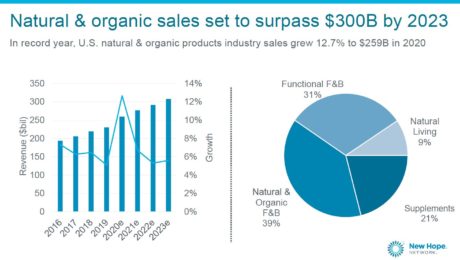

Sales of natural and organic products grew nearly 13% to $259 billion in 2020 , “despite the pandemic and, in some ways, because of the pandemic.”

“It’s very strong and, in many ways, it’s never been stronger,” says Carlotta Mast, senior vice president of the New Hope Network (producers of the event). Between pandemic-driven pantry loading, new brand exploration and the drive to purchase healthier, natural products, “people tried those new brands and, in many cases, they stuck with them, especially across the food and beverage categories.”

Mast shared these stats during the State of the Natural & Organic presentation at Natural Products Expo East. But forecasts show sales growing at a slower pace this year, to $271 billion. By 2023, sales are projected to surpass $300 billion.

Natural foods and beverages (including most fermented products) account for 70% of all natural product sales (the rest includes items like supplements and home and pet care products). Natural products are growing three times as fast as their mainstream counterparts.

“Not only were we growing quickly, we were outpacing the rest of the store…not only did our sales accelerate, they drove the whole (food) industry forward,” says Kathryn Peters, executive vice president at SPINS (a data provider for natural, organic and specialty products). “We’re finding consumers are coming and staying and continuing to buy more.”

Expo East Returns In-Person

Expo East is the first major food trade show to meet in-person since the Covid-19 pandemic shuttered events in March 2020. New Hope Network used a hybrid virtual and in-person model to produce the show, live-streaming the conference portion to virtual attendees.

“It was really exciting and satisfying to be back on a live show floor, interacting with people again. There was a real buzz,” says Chris Nemchek, TFA’s buyer relations director. “On day 1, you could tell there was a lot of pent-up demand.”

Health precautions were increased. Attendees had to show a Covid-19 vaccination card or a negative Covid-19 test administered within 72 hours. Masks were mandatory. Badges were no longer distributed to all attendees, only being printed upon request.

Food sampling, too, was much different than at a typical pre-pandemic trade show. Samples were only given by a gloved brand representative at an exhibitor’s booth. Food was stored behind sneeze guards, and surfaces were wiped down frequently.

“Exhibitors gave away less product, but the product they did give away was for more productive reasons — the people who took the sample really wanted it,” Nemchek notes.

“It was a good step back towards normal, but it wasn’t normal,” he adds. The size of the crowd at the show was not close to pre-pandemic levels (attendance numbers have not been released). But Nemchek notes that New Hope should still be pleased. “There’s now more confidence in the industry in putting on a food show again.”

Immune Health Driving Purchases

The natural and organic industry’s most popular products continue to be ones supporting immunity, health and wellness. Those attributes were consumer’s top purchase priorities in 2020, and remain strong in 2021.

Paleo (+25%), grain-free (+17%) and plant-based (+13%) foods and beverages registered the strongest sales growth. Plant-based products have seen especially strong sales over the past two years.

“Covid was a major driver for this boost in sales growth,” Mast says. Now “it’s our opportunity to keep those consumers.”

Consumers are exploring how they can use their diet as the first line of defense against illness, Peters adds. Immunity-related ingredients traditionally found on the supplement aisle, like cider vinegar, collagen, elderberry, moringa and ashwagandha,are now in grocery and refrigerated products.

“It’s revolutionizing the aisles in the store,” Peters says.

Changing Grocery Store Shelves

The U.S. is diversifying faster than predicted as well, and those demographic changes are influencing what’s selling. International foods are outperforming in grocery sales, growing at a 21% rate (compared with U.S. food at 16%).

“This is a huge shift for our country,” Mast says. “We’re seeing that, across our industry, more consumers are looking for that multicultural food.”

Mast notes, though, that leadership of the natural and organic products industry does not reflect the U.S. population.More BIPOC representation is needed on i company boards and leadership teams.

Shopping with Values

Consumers’ social and environmental values are also driving purchasing behavior. A survey by Nutrition Business Journal and SPINS found 76% of natural shoppers pay more for high-quality ingredients, 57% avoid buying food grown on industrial feedlots or chemical-intensive farms and 53% will pay more to support businesses that are socially- or environmentally-responsible. Consumers want companies to take social and political stances that reflect their own values.

“Our industry, because of our size, our scale and our influence, we could truly help create solutions to these problems and be part of building that new future,” Mast adds. “Think about the changes that we could help create for people, animal, planet — but it’s if we chose to do so.”

- Published in Business, Food & Flavor

Ireland’s Fermented Drinks Under Scrutiny

After a study found 91% of plant-based, fermented drinks in Ireland make unauthorized health claims, the Food Safety Authority of Ireland (FSAI) has published a guide on how to produce such beverages safely and label them accurately.

The FSAI examined 32 unpasteurized drinks currently sold on the Irish market – including kombucha, kefir and ginger soda – and found that most did not comply with EU and Irish food labelling and health regulations. The study found 13% had alcohol levels above labelling thresholds, and 75% lacked required label information, like the address of the producer and “best-before” date.

“The methods used in producing unpasteurized fermented plant-based products can be difficult to manage,” notes Dr. Pamela Byrne, FSAI chief executive. “The guidance will help producers to achieve consistent production methods, safe storage, safe handling and safe transportation of fermented beverages.”

Read more (Agriland)

Wood Alternative from Kombucha Waste

A new wood alternative made from a byproduct of kombucha brewing waste won this year’s James Dyson Award, which celebrates problem-solving design. The material, called Pyrus, was invented by sustainable-design student Gabe Tavas. Tavas’ company, Symmetry, makes small items from Pyrus that replicate exotic woods like mahogany or purpleheart (two wood types found in the rainforest and endangered by aggressive deforestation).

Tavas was inspired to create Pyrus after seeing designers use kombucha bacterial cellulose (the film that grows on top of the beverage during brewing) in various projects. Tavas was struck by the fact that trees are made from cellulose, and he began experimenting in his dorm room with the waste from his own kombucha brewing. He eventually partnered with local Chicago producer, KombuchAde, which supplies Tavas with 250 pounds of cellulose a day.

Pyrus is made by pouring cellulose into a mold, adding agar (an algae-based binding gel), and then dehydrating and compressing it. The synthetic wood can be sanded and cut, but will decompose in contact with water.

Read more (Fast Company)

Q&A: Sebastian Vargo, Vargo Brother Ferments

Sebastian Vargo was an up-and-coming chef on the Chicago food scene when the Covid-19 pandemic hit and shuttered restaurants. Laid off from his job as head chef at Merchant Restaurant, Vargo experimented with different gigs — yoga teacher, realtor, even t-shirt graphic designer — but kept coming back to his passion: creating food.

So Vargo and his fiancée, Taylor Hanna, launched Vargo Brother Ferments. They produce a creative line-up of fermented condiments, sauces and beverages, including items like a pickled garlic sauce, chipotle beet sauerkraut, Mighty Vine tomato vinegar, Concord grape kombucha and a Bulgarian yogurt with fermented strawberry jam and miso peanut butter.

“Ultimately, I’m a flavor chaser,” Vargo says. “Fermentation is not really an obligation, it’s a necessity to really unlock certain flavors.”

Most of what they make is seasonal, created from fresh ingredients sourced locally from Chicago community gardens or out of Vargo’s backyard garden. Flavors heralding back to Vargo’s childhood are also featured. Collard greens kimchi is one example, featuring the leafy vegetable frequently served at Vargo’s family dinner table as he grew up in Detroit.

“You can’t help but find a little bit of nostalgia in what you make. Flavors are so connected to memories,” Vargo says. He recalls his mother’s buttery cornbread, her pinto beans flavored with a smoked ham hock and his grandmother’s braised short ribs with sauerkraut. “We were this African-American family in the Midwest in the ‘90s with Southern heritage, so some of my food preserves some of that history. With fermentation, there’s an intersection of both physical preservation and historical preservation. My fermented vegetables are an homage to the past, presenting certain vegetables in interesting and complex ways.”

Vargo and Hanna currently run their business from their home kitchen, selling over Instagram, at farmers markets and through collaborations with local restaurants around the Chicago area. They’re nearing the end of a Go Fund Me campaign to help move Vargo Brother Ferments into a commercial kitchen and, eventually, a storefront. .

Below is an edited Q&A between Vargo and The Fermentation Association.

The Fermentation Association: How did you first get into cooking?

Sebastian Vargo: My origin is with my grandmother. My mom worked really hard, she worked nights and then she was going to school as well. My grandmother was in our household a lot, she taught me and my brothers [the namesake behind Vargo Brother Ferments] a lot of life skills, how to box, how to play basketball, how to cook. I have fond memories of eating sauerkraut as a child out of a coffee mug with a fork. She was my earliest inspiration, I have fond memories of my grandma in the kitchen.

TFA: And how did you get into fermentation?

SV: My grandma introduced me to sauerkraut. It was such an exciting flavor, I hadn’t experienced the brininess of lactic fermentation, the way it feels on my tongue and cheeks. My mom loved to take us to local delis and we loved Reuben sandwiches. We’d go to a lot of Jewish delis in southeast Michigan, and they had salt brine pickles. That was a real fermented pickle, that flavor is something, too, that really kind of jump started my interest in fermentation.

And then, just working with cool chefs. A new part of my mind was unlocked at every restaurant. Great chefs helped cultivate my love of fermentation. Being in the industry in Chicago is so cool. Every last one of us, we’re all trying to experiment and see what we can do with flavors. When I worked for Stephanie Izard at Girl & the Goat, we were doing kimchi for certain dishes. At Schwa with Brian Fisher and later Wilson Bauer, we made our own yogurt and fermented our leeks, our apricots. And then when I worked for Tony Quartaro at Dixie, he was really pushing the envelope with this Southern-style restaurant where we took inspiration from around the world in a way and applied it to this Southern technique. We had some peaches come in that were underripe, we couldn’t use them for the actual dish, so instead he mixed it with some rum and taught me how to make a vinegar out of it.

TFA: What took you from Detroit to cheffing in Chicago?

SV: It was one Le Cordon Bleu commercial. I was young, I was in a bit of a crossroads and I made the decision to go to the Le Cordon Bleu culinary school in Chicago. I was working at the Salvation Army at the time and I got on the Megabus with my little thrift bags and maybe $800. I had no plans, I found out $800 will not get you an apartment in Chicago, so I stayed in hostels. Before I got enough money for culinary school, I worked as a canvasser to make money.

TFA: March 2020. You are the head chef at Logan Square’s Merchant and your fiancée was cooking at the Ace Hotel. Then Covid-19 lockdowns happen. Tell me how your lives changed.

SV: Merchant was the first restaurant where I was head chef, it was fun. We made our own hot sauces, we fermented pickles. But once I had the call that we were closing for Covid, I was ready to figure something out. I was a little bit burnt out from the industry at the time. I was ready to leave, it’d been a lot of pressure and a lot of stress for a while. So, like a lot of Americans, we took the unemployment. I had never been on unemployment. Being unemployed gave me a chance to finally reset. I was working up to 120 hours a week cheffing around. Now I could see what else is out there.

The whole time I was looking outside of the industry, me and Taylor were still doing a lot of experiments in the kitchen. We were making a lot of bagels, making pickles. I have a friend Joe Morski who runs a one-man sandwich operation called Have a Good Sandwich. It’s like a rotating sandwich club in Chicago. Meanwhile, I was trying to start a pickle club, and I asked him if he wanted to serve my pickles in the lunch pack for his sandwiches. That was my first foray into getting my pickles out there. From there, we just started peddling our jars.

TFA: What was the transition to your own business?

SV: To this day, there’s so few fermented, unpasteurized pickles on the market. It wasn’t even a search for a niche, it was something I love to do and I was excited to share my flavor palette with the public. Fermentation is a fun way to be creative, to use it as a platform for new dishes, to play aground with colors. It’s definitely been a great medium to pursue my love of food, of art. Feeding people is my love language. And fermentation is definitely something that’s going to live on forever. It’s wellness, it’s never going to go out of style.

TFA: Tell me about your G-Dilla pickle. That’s a customer favorite. What makes it so special?

SV: The G-Dilla pickle is a flagship that’s always in season. The name G-Dilla, we have blank labels and I didn’t want to write “Garlic Dill” each time. So I started G-Dilla as an homage to J-Dilla, a great producer [and rapper from Detroit].

The taste is akin to a Jewish deli, a garlic dill pickle, the one that would accompany a Reuben sandwich. I just take it kind of a step further with the herbs and the garlic. We use black tea in our pickle brine, it is a fun way to add tannins to the mix which provides that nice, crunchy skin. We really enforce the flavors through fresh herbs, fresh dill from our backyard, parsley, grape leaves, fresh bay leaf and we add lots of garlic and toasted block peppercorn and mustard seed. Maybe a little gochujang, some turmeric. You bite into one and you’re getting that loud crunch and you’re just getting that lactic acid zing that’s electrifying the flavor. It makes you stop what you’re doing, you can’t talk through it, you have to finish chewing and enjoy the whole experience. It’s been a journey — I think back to the first pickle I made to now and it’s something I’ve kept at, I’m a student of the game, always striving to learn more techniques and refine what I’m doing.

TFA: Why do you think more and more chefs are exploring fermentation?

SV: I think so many chefs are seeing the flavor benefits alone. Food fermentation offers a more nuanced flavor that you just can’t achieve the same way. Fermentation is in everything that we do, everything that we eat. There is really an endless source of inspiration and flavor for chefs. We’ve seen the interest pick up in fermentation, but it’s not a fad in the food world. Fermentation is something that is here to stay, with the recent explosion and interest in it, fermentation will find a nice settling place in food.

TFA: What do you think is the future of fermentation?

SV: I would like to see a future in which fermentation is no longer just a trending topic, something that everyone acknowledges for its real health benefits. So people aren’t just taking a probiotic gummy, they know they can get probiotics easily through so many foods. Society is at a place where we are not quite as healthy as we should be. Maybe we can make fermentation convenient, maybe we can show people that it’s not hard, we can show folks that there’s food you can have that has enhanced flavors and there’s something in fermentation for everyone.

- Published in Business, Food & Flavor

Noma Finally Earns 3rd Michelin Star

Fourteen years after earning two stars from the Michelin Guide, Noma was finally awarded the illustrious third star.

“After so many years of working together, to finally achieve something like this is extremely special,” says René Redzepi, chef and co-owner of the Copenhagen-based restaurant, during Michelin’s ceremony for Nordic countries earlier this month. Redzepi said the announcement left him surprised and flabbergasted. “I’m completely blown away, it’s a new feeling for me. This opportunity happens once in your lifetime.”

Long lauded as one of the top restaurants in the world, Noma has an innovative fermentation lab and test kitchen that creates wildly imaginative and ingenious dishes. Their summer menu featured an edible candle made with cardamom, saffron and a wick of silvered walnut; a salad made with reindeer penis; and a cold-pressed beetroot juice served in a flower pot adorned with a ladybug made from raspberry and black garlic .

The reactions from food industry professionals echoed the same sentiment — the third star was overdue.

James Spreadsbury, restaurant manager at Noma, said during the ceremony that the staff at the restaurant has been patient. “At some point, we kept on and didn’t expect anything would change. But we were still so proud of what we did and believed in what we did. After so many years of working together, to finally achieve something like this is extremely special.”

Redzepi was also honored by Michelin. The Chef Mentor award, given annually to a chef sharing their knowledge to help others, was presented to him by Peyman Sabet, the vice president of business development for Michelin.

“It’s really about innovation and making the path for a new generation of chefs,” Sabet said.

Redzepi said he was humbled to receive the award. He noted that, when Noma opened 18 years ago, “I was a terrible leader…when you are in the industry, you find yourself becoming a head chef and you don’t have the tools to actually figure out how are you doing to do this, how are you doing to lead and inspire a team.”

He said years ago he “promised himself this is not who I wanted to be.”

“One of the most enjoyable things I have in my professional career is to see someone that’s been a part of your own success, but when they leave they have their own success. That’s really really enjoyable.”

Noma is proud of their alumni and highlights them on their website. Reads the webpage: “Our chef René was himself a stagiaire [a cook who works briefly, for free, in another chef’s kitchen] around the world before opening Noma. It is a part of sharing ideas and knowledge that is quite special in our trade. We wouldn’t want to be without stagiaires and we believe that everyone that has been through Noma shares in part of our success.”

Former Noma chefs include: David Zilber (nowat bioscience company Chr. Hansen), Thomas Frebel (head chef at INUA in Tokyo), Dan Giusti (founder of chef training company Brigaid), Matt Orlando (head chef at Amass Restaurant in Copenhagen), Søren Ledet (owner and restaurant manager at Geranium in Copenhagen) andMads Refslund (head chef of ACME in New York City)

- Published in Business, Food & Flavor

Native American Brewery with Traditional Flavors

Bow & Arrow Brewing in New Mexico is part of two small but growing groups in the U.S. — it is both female- and Native American-owned.

Bow & Arrow locally sources their traditional Native American ingredients (blue corn, Navajo tea, three-leaf sumac) for their seasonal sour beers. The hops they use — subspecies neomexicanus — were used for their antiviral properties by the Navajo people in the Southwest,who put them in teas and salves. The brewery owners — Missy Begay and Shyla Sheppard — forage for hops in the mountains near Albuquerque. They also give their spent brewing grains to a local Native American family for use as feed for their livestock.

Begay, pictured left (who is Diné [Navajo]) and Sheppard, pictured right (a member of the Three Affiliated Tribes [Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara]) met at Stanford University in 2000. They took different career paths, but both fell in love with craft beer and homebrewing. They opened Bow & Arrow Brewing Co. in 2016.

“There is a sweetness to the land here, and all of this is sacred. We hope, as Native American women brewery owners, that people understand the story we have to tell,” Begay says.

Read more (Outside)

- Published in Business, Food & Flavor