“Our Customers Do Not Even Know What is a Fermented Item”

Fermentation is cloaked in mystery for many — it’s bubbly, slimy, stinky and not always Instagram-ready. In The Fermentation Association’s recent member survey, this lack of

understanding of fermentation and its flavor and health attributes among consumers was cited by 70% of producers as a major obstacle to increased sales and acceptance of fermented products.

“We get so many questions from our readers about fermentation. People are very interested, but have very, very little knowledge about it,” says Anahad O’Connor, reporter for The New York Times. O’Connor has written about fermented foods multiple times in the last few months, and those articles were among The Times’ most emailed pieces of 2021. “I think there’s a huge opportunity to educate consumers about fermented foods, their impact on the gut and health in general.”

O’Connor spoke on consumer education as part of a panel of experts during TFA’s conference, FERMENTATION 2021. Panelists — who included a producer, retailer, scientist, educator and journalist — agreed consumer education is lacking. But the methods of how to fill that gap are contested.

How to Tell Consumers “What is a Fermented Food?”

There are differences between what is a fermented product and what is not — a salt brine vs. vinegar brine pickle, or a kombucha made with a SCOBY or one from a juice concentrate, for example.

“I can tell you that the majority of our customers do not even know [what is a] fermented item,” says Emilio Mignucci, vice president of Philadelphia gourmet store Di Bruno Bros., which specializes in cheese and charcuterie. When customers sample products at the store, they can easily taste the differences between a fermented and a non-fermented product, Mignucci says. But he feels the health benefits behind that fermented product are not the retailer’s responsibility to communicate. “I need you guys [producers] to help me deliver the message.”

“Retailers like myself, buyers, we want to learn more to be able to champion [fermented foods] because, let’s face it, fermented foods is a category that’s getting better and better for us as retailers and we want to speak like subject matter experts and help our guests understand.”

Now — when fermentation tops food lists and gut health is mainstream — is the time for education.

“This microbiome world that we’re in right now is sort of a really opportune moment to really help the public understand what fermented foods are beyond health,” says Maria Marco, PhD, professor of food science at the University of California, Davis (and a TFA Advisory Board Member).

Kombucha Brewers International (KBI) created a Code of Practice to address confusion over what is or is not a kombucha. KBI is taking the approach that all kombucha is good, pasteurized or not, because it’s moving consumers away from sugar- and additive-filled sodas and energy drinks.

“That said, consumers deserve the right to know why is this kombucha at room temperature and this kombucha is in the fridge and why does this kombucha have a weird, gooey SCOBY in it and this one is completely clear,” says Hannah Crum, president of KBI. “They start to get confused when everything just says the word ‘kombucha’ on it.”

KBI encourages brewers to be transparent with consumers. Put on the label how the kombucha is made, then let consumers decide what brand they want to buy.

Should Fermented Products Make Health Claims?

Drew Anderson, co-founder and CEO of producer Cleveland Kitchen (and also on TFA’s Advisory Board), says when they were first designing their packaging in 2013, they were advised against using the term “crafted fermentation” on their label because it would remind consumers of beer or wine. But nowadays, data shows 50% of consumers associate the term fermentation with health.

“In the last five to six years, it’s changed dramatically and people are associating fermentation as being good for them, which is good for my products,” he says.

Cleveland Kitchen, though, does not make health claims on their fermented sauerkraut, kimchi and dressings. Anderson says, as a small startup, they don’t have the resources to fund their own research. They instead attract customers with bold taste and striking packaging.

“We’re extremely cautious on what we say on the package because we don’t have an army of lawyers like Kevita (Pepsi’s Kombucha brand), we don’t have the Pepsi legal team backing us here,” Anderson says. Cleveland Kitchen submits new packaging designs in advance to regulators, to make sure they’re legally acceptable before rolling them out.

O’Connor says taste is the No. 1 driver for consumers. This is why healthful but sticky and stinky natto (fermented soybeans) is not a popular dish in America, but widely consumed in Japan.

“Many American consumers, unfortunately, aren’t going to gravitate toward that, despite the health benefits,” he says.

Crum disagrees. “Health comes first,” she says. As more and more kombucha brands emphasize lifestyle, and don’t even advertise their health benefits, she feels they are doing a disservice to the consumer. “Why pay that much money for kombucha if you don’t know it’s good for you too?”

- Published in Business, Food & Flavor, Health, Science

Fermentation Tourism

The state of Pennsylvania has created a unique tourist experience, Pickled: A Fermented Trail. The self-guided, culinary tour showcases fermented food and drink from around the state.

The fermented trail is broken into five regional itineraries, and includes historic businesses, artisanal food makers and large producers. Stops range from an Amish gift shop that ferments root beer to a master chocolatier, from a kombucha taproom to a fermentation-focused restaurant, and from a fourth-generation cheesemaker to a convenience store that makes its own pickles, sauerkraut and vinegar. Mary Miller, cultural historian and professor, spent two years designing the trail.

“Cultured foods have been part of PA’s culinary culture since the beginning,” reads the Visit Pennsylvania Pickled: A Fermented Trail website. “Many groups that have migrated to Pennsylvania throughout history were fond of fermented foods for both health and flavor, as well as for preserving food through the winter.”

The website also features a history of fermented food and drink, both regionally and globally. It shares a brief overview of root beer, which was created in Pennsylvania as a sassafras-based, yeast-fermented root tea. And it notes that, while Germans brought sauerkraut to the state, the Chinese are believed to have been the first to ferment cabbage.

The fermented trail is one of Pennsylvania’s four new culinary road trips, along with those highlighting charcuterie, apples and grains. These paths aim to showcase the state’s culinary history, and preserve its foodways.

This unique culinary adventure — the first we have seen at TFA — could be a model for tourism in other states and countries.

Read more (Food & Wine)

- Published in Business

Pandemic Closes 75-Year-Old Sauerkraut Producer

Beloved Canadian sauerkraut brand Tancook is shutting down after 75 years. The iconic Nova Scotia traditional sauerkraut, which is packaged in a milk carton, was even the subject of Philip Moskovitz’s book Adventures in Bubble and Brine: What I Learned from Nova Scotia’s Masters of Fermented Foods, Craft Beer, Cider, Cheese, Sauerkraut, and More.

Owners Hatt and Son Ltd. announced the closure on social media, posting “due to financial implications of the Covid-19 pandemic, we have made the difficult decision to end production.” Owner Cory Hatt said “difficult decisions” had to be made and he did not want to discuss it further with media outlets.

Tancook’s history is rich in Canada. German immigrants found that cabbage thrived on Nova Scotia’s Big Tancook Island, where they fertilized it annually with seaweed. Tancook sauerkraut became a popular condiment for seafaring ships, who would pick up barrels of it to combat scurvy in sailors and provide them nutrition during long, maritime winters.

Tancook Brand Sauerkraut was later produced commercially in Lunenburg County in Nova Scotia, using the same recipe brought from the island by the great-grandfather of Hatt. It remained a traditionally fermented product.

A social media campaign has already launched, aiming to find a buyer for the brand.

Read more (CBC)

- Published in Business

The Rise of Fermented Foods and -Biotics

Microbes on our bodies outnumber our human cells. Can we improve our health using microbes?

“(Humans) are minuscule compared to the genetic content of our microbiomes,” says Maria Marco, PhD, professor of food science at the University of California, Davis (and a TFA Advisory Board Member). “We now have a much better handle that microbes are good for us.”

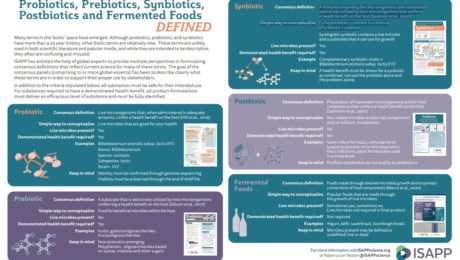

Marco was a featured speaker at an Institute for the Advancement of Food and Nutrition Sciences (IAFNS) webinar, “What’s What?! Probiotics, Postbiotics, Prebiotics, Synbiotics and Fermented Foods.” Also speaking was Karen Scott, PhD, professor at University of Aberdeen, Scotland, and co-director of the university’s Centre for Bacteria in Health and Disease.

While probiotic-containing foods and supplements have been around for decades – or, in the case of fermented foods, tens of thousands of years – they have become more common recently . But “as the terms relevant to this space proliferate, so does confusion,” states IAFNS.

Using definitions created by the International Scientific Association for Postbiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP), Marco and Scott presented the attributes of fermented foods, probiotics, prebiotics, synbiotics and postbiotics.

The majority of microbes in the human body are in the digestive tract, Marco notes: “We have frankly very few ways we can direct them towards what we need for sustaining our health and well being.” Humans can’t control age or genetics and have little impact over environmental factors.

What we can control, though, are the kinds of foods, beverages and supplements we consume.

Fermented Foods

It’s estimated that one third of the human diet globally is made up of fermented foods. But this is a diverse category that shares one common element: “Fermented foods are made by microbes,” Marco adds. “You can’t have a fermented food without a microbe.”

This distinction separates true fermented foods from those that look fermented but don’t have microbes involved. Quick pickles or cucumbers soaked in a vinegar brine, for example, are not fermented. And there are fermented foods that originally contained live microbes, but where those microbes are killed during production — in sourdough bread, shelf-stable pickles and veggies, sausage, soy sauce, vinegar, wine, most beers, coffee and chocolate. Fermented foods that contain live, viable microbes include yogurt, kefir, most cheeses, natto, tempeh, kimchi, dry fermented sausages, most kombuchas and some beers.

“There’s confusion among scientists and the public about what is a fermented food,” Marco says.

Fermented foods provide health benefits by transforming food ingredients, synthesizing nutrients and providing live microbes.There is some evidence they aid digestive health (kefir, sourdough), improve mood and behavior (wine, beer, coffee), reduce inflammatory bowel syndrome (sauerkraut, sourdough), aid weight loss and fight obesity (yogurt, kimchi), and enhance immunity (kimchi, yogurt), bone health (yogurt, kefir, natto) and the cardiovascular system (yogurt, cheese, coffee, wine, beer, vinegar). But there are only a few studies on humans that have examined these topics. More studies of fermented foods are needed to document and prove these benefits.

Probiotics

Probiotics, on the other hand, have clinical evidence documenting their health benefits. “We know probiotics improve human health,” Marco says.

The concept of probiotics dates back to the early 20th century, but the word “probiotic” has now become a household term. Most scientific studies involving probiotics look at their benefit to the digestive tract, but new research is examining their impact on the respiratory system and in aiding vaginal health.

Probiotics are different from fermented foods because they are defined at the strain level and their genomic sequence is known, Marco adds. Probiotics should be alive at the time of consumption in order to provide a health benefit.

Postbiotics

Postbiotics are dead microorganisms. It is a relatively new term — also referred to as parabiotics, non-viable probiotics, heat-killed probiotics and tyndallized probiotics — and there’s emerging research around the health benefits of consuming these inanimate cells.

“I think we’ll be seeing a lot more attention to this concept as we begin to understand how probiotics work and gut microbiomes work and the specific compounds needed to modulate our health,” according to Marco.

Prebiotics

Prebiotics are, according to ISAPP, “A substrate selectively utilized by host microorganisms conferring a health benefit on the host.”

“It basically means a food source for microorganisms that live in or on a source,” Scott says. “But any candidate for a prebiotic must confer a health benefit.”

Prebiotics are not processed in the small intestine. They reach the large intestine undigested, where they serve as nutrients for beneficial microorganisms in our gut microbiome.

Synbiotics

Synbiotics are mixtures of probiotics and prebiotics and stimulate a host’s resident bacteria. They are composed of live microorganisms and substrates that demonstrate a health benefit when combined.

Scott notes that, in human trials with probiotics, none of the currently recognized probiotic species (like lactobacilli and bifidobacteria) appear in fecal samples existing probiotics.

“There must be something missing in what we’re doing in this field,” she says. “We need new probiotics. I’m not saying existing probiotics don’t work or we shouldn’t use them. But I think that now that we have the potential to develop new probiotics, they might be even better than what we have now.”

She sees great potential in this new class of -biotics.

Both Scott and Marco encouraged nutritionists to work with clients on first improving their diets before adding supplements. The -biotics stimulate what’s in the gut, so a diverse diet is the best starting point.

Katz on Fermentation, Ancient & Modern

When Sandor Katz was asked to teach his first fermentation workshops in the early ‘90s, he figured it would have only niche appeal. Instead, people filled his workshops, begging for more information and calling on him to host similar events all over the U.S. “People [were] hungry for more information on fermentation,” he says.

“Humans didn’t invent fermentation. Fermentation is a natural phenomenon that existed before we did,” Katz says, speaking from in front of a wall of ferments and spices in his home kitchen in Tennessee. “Fermentation is an essential part of how people everywhere make effective use of whatever food resources are available to them. Food fermentation is not precious; fermentation is practical.”

Katz was a keynote speaker at the FERMENTATION 2021 conference. He shared his personal journey into the subject as well as his thoughts on fermentation as a natural phenomenon.

Fermentation as Trend

Katz says people are excited about fermentation for different reasons — some have memories of fermenting with their grandparents and want to try it at home, others are immigrants wanting to recreate dishes from their native countries, some are farmers hoping to preserve a surplus of produce, others are interested in the health benefits and some are foodies chasing the delicious flavor.

He hates equating fermentation with trends, preferring the term “fermentation revitalization” — the demographics of people currently making fermentation “trendy” again hasn’t really changed in the last 30 years.

“Fermentation has been so important to food traditions everywhere, and yet because of factory food production, one-stop shopping convenience foods, fewer and fewer people were practicing fermentation,” Katz said, recalling his workshops in the early days. “It was becoming more mysterious to people. Now there’s no denying that fermentation is trending. There’s a heightened awareness of fermentation, but people don’t realize the products of fermentation have been so integral to how everybody, everywhere eats. Without even thinking about fermentation, people have always been eating products of fermentation.”

The “War on Bacteria”

But there has long been fear around fermentation from some consumers. Katz says many people “project their anxiety about bacteria onto the idea of fermentation.”

“For people of my generation and older, we never heard anybody say anything positive about bacteria. The degree that bacteria were talked about at all, it was about how dangerous they are and how much they need to be avoided. I grew up in a period that could be described as the war on bacteria, this idea that bacteria are pathogenic, bacteria are dangerous to us, bacteria must be avoided and you know we have an arsenal of chemicals that we can use to kill bacteria as needed to keep us safe.”

The U.S Department of Agriculture has never had a case of foodborne illness from fermented food or beverages, Katz notes. “Statistically speaking, fermented vegetables are safer than raw vegetables.”

Facing people’s questions and fears motivated Katz to write his first book, The Art of Fermentation. This month, he released his 6th title, Fermentation Journeys: Recipes, Techniques, and Traditions from Around the World.

Fermenting the Future

Katz is an advocate for decentralizing food production, replacing a global supply chain with local, farm-fresh sources. Though this will raise the cost of food, it will put fermentation as a key means of preserving a surplus of seasonal crops, Katz notes.

Even as more and more chefs and producers apply different processes to different substrates and play with flavor, Katz says the fundamental processes remain the same. Nothing new has been invented in fermentation, which dates back 10,000 years.

“Fermentation of the future grows out of the techniques and traditions of the past,” he says. “Anything you can possibly eat can be fermented, so I’m never surprised when something is fermented.”

Katz shared his story of fermenting a goat on the rural Tennessee farm he lived on in the ‘90s. After the animal was butchered, he took the leftover pieces and fermented them for a few weeks in a mix of miso, yogurt and sauerkraut juice. When cooked, the meat released a strong aroma, a scent that became legendary on the farm. But, Katz says, “It was delicious. Like many things, it had a stronger aroma than flavor.”

Health Benefits Come with Warning Labels

When asked about the curative health benefits of fermented foods, Katz does not mince words. He wrote in Wild Fermentation that fermented foods were an important part of his healing when he was diagnosed with HIV in 1991. Since then, numerous media outlets have twisted his story, writing that Katz cured himself from HIV with fermented foods.

“I have become much more cautious about how I talk about this,” he says. “There’s a lot of highly speculative information out there…and I’ve never seen data that would suggest that.”

Katz says he’s careful to rely on reputable scientific studies for data on fermentation’s health benefits. He says he’s read articles claiming kombucha will prevent hair from going gray. Pointing to his full head of gray hair, Katz smiles and says “When I started teaching about fermentation, my hair didn’t look like this. Time marches on.”

“Food has profound implications for our health and well-being and for how we feel, but singular foods are very rarely the cure to specific diseases. …There are many benefits to fermentation, whether it is simply from pre-digestion of nutrients that makes nutrients more bioavailable and accessible to us or whether it’s from the probiotics or whether it’s from metabolic byproducts which can be extraordinarily beneficial to us.”

- Published in Food & Flavor

How Important is Consumer Education?

This is the second in a series of articles that TFA will be releasing over the next few months, analyzing trends from our Member Survey.

Fermentation is cloaked in mystery for many consumers — it’s bubbly, slimy, stinky and not always Instagram ready.

So how can fermentation producers appeal to potential consumers? What’s the best way to share fermentation’s flavor and health attributes?

In The Fermentation Association’s membership survey on industry trends, a better-educated consumer was identified as a priority. When asked what would foster increased consumption of fermented foods and beverages, the top item for nearly 70% of producers was greater consumer understanding of fermentation and familiarity with the flavors associated with fermentation.

“More than wanting to sell a product, I want people to know the information,” says Sebastian Vargo of Vargo Brothers Ferments (who is speaking at FERMENTATION 2021). The Chicago-based brand sells ferments like pickles, sauces and kombucha. “I believe preventative health starts with fermentation. I’m explaining the difference between a pickle you see on the shelf versus a pickle you see in the refrigerator. But I’m also teaching people to power up their pantry, sauce up their life with condiments.”

Health vs. Flavor

Producers say they struggle sharing fermentation’s benefits with consumers. There are not enough peer-reviewed scientific studies on many fermented products to be the basis for health claims.

“We feel a responsibility as a fermented food company to entice customers into trying these hugely beneficial and delicious products,” says Savita Moynihan, who owns SavvyKraut in Brighton, UK, with her husband Stevo. But, “with sauerkraut, it is generally understood that raw and unpasteurised kraut is good for you but once you try to elaborate on live culture vs probiotics it gets complicated, more than it needs to be.”

Can a brand claim to include probiotics? Producers feel that guidance is not clear.

“There is confusion here that we feel needs to be ironed out in order to loosen the reins so fermenters can promote their products and their benefits with much more confidence,” she adds.

Moynihan says that, when SavvyKraut sells at farmers markets and local shops, they try to communicate two main things to consumers. First, the health benefits, like enhanced vitamin and nutrient contents, increased fiber and an aid to a diverse gut and digestive system. Second, the delicious flavor.

“The process of fermentation really enhances the flavours and creates an entirely new type of flavour which can elevate any meal,” Moynihan adds.

Lack of Tastings Hurting Efforts

One of the best ways to familiarize consumers with fermentation is for them to taste a product — flavor is a great marketing tool. But COVID-19 has hurt these efforts. Producers are unable to stage in-store demonstrations, offer samples at farmer’s markets or host in-person events. This has been especially hard for kombucha brewers, says Hannah Crum(who is also speaking at FERMENTATION 2021), president of Kombucha Brewers International (KBI).

“We still have such a big part of the population who don’t drink kombucha or don’t even know about [it]; we still have a lot of work in education,” Crum says.

Joshua Rood, CEO of Dr Hops Hard Kombucha, confirms, adding: “It continues to be very difficult to grow our brand and the whole category without live events.”

“The inability to do live tastings in 2020 had a significant diminishing impact on our sales during the pandemic,” he continues. “One of our main distinctions as a brand is superior taste. Consumers, however, do not believe claims about that unless they experience it for themselves. Even now we are significantly hampered by the lack of large beer festivals and street fairs. An artisanal craft brand like Dr Hops needs those live interactions!”

The Knowledge Gap

Despite the lack of in-store tastings, experts at New Hope Network (producers of the Natural Products Expos) say brands have a great opportunity — now, more than ever, during the COVID-19 pandemic — to connect with their consumers.

New Hope’s 2021 Changing Consumer Survey found U.S. consumers are not satisfied with their current health. Only 8% say they’re “extremely satisfied” with their health today, compared with 20% in 2017. Nearly 80% of consumers understand that diet greatly influences their health (79%). But achieving good health is both a goal and a struggle for consumers — and this is where brands can step in.

“There’s a gap to be bridged,” says Eric Pierce, vice president of business development for New Hope Network, during a session “Understanding Your Consumers” at the most recent Expo East. “I see it as our opportunity and our responsibility to help consumers translate healthy intentions into healthy behavior, either in how we’re educating them in our stores, the products that we’re innovating or the ways we’re communicating. Getting better at communicating can help them with solutions.”

A consistent, transparent, well-communicated message — from product label to social media page to website — is important. Pierce says consumers quickly see past “shallow marketing claims.”

“Leave a trail of breadcrumbs people can find,” Pierce advises. “You don’t have to communicate everything all at once, but allow people to follow a trail to the deeper story. When consumers want to find that trail, if it’s not there, they’ll quickly write you off as shallow with unbacked claims.”

Amanda Hartt, market research manager at New Hope, suggests putting a QR code on a product label that links to the science backing the benefits of your ingredients. Or partnering with a registered dietitian on social media to highlight how to use your product as part of a healthy diet.

[To learn more about this topic, register for FERMENTATION 2021 to hear one of the keynote panels “Educating Consumers About Fermentation.”]- Published in Business, Food & Flavor, Science

“A modern-day Johnny Appleseed”

GQ interviews “The Godfather of the Fermentation Revival,” Sandor Katz. In the Q&A, Katz shares how a cabbage surplus in his first garden turned into an obsession with fermentation. Katz teaches fermentation workshops and gives fermentation talks around the world (he will be speaking at FERMENTATION 2021). He’s also now the author of six books on fermentation, including the recently-published Fermentation Journeys.

The article says Katz “has become a globe-trotting mascot for the power of bacteria and yeast to create delicious food, a kind of modern-day Johnny Appleseed of tangy, savory flavors.”

Katz shares how he’s interested in learning more about the Chinese techniques for fermenting vegetables; he believes China is where fermenting vegetables in salt first originated. He also addresses his misquoted healing. Katz has lived with H.I.V for more than 30 years, but he says eating fermented foods does not cure AIDS. Katz does believe he’s never been sick from the antiretroviral drugs he takes to manage the disease because he eats fermented foods regularly.

Read more (GQ)

- Published in Food & Flavor

Decreasing Food Waste Through Fermentation

Will fermentation be key to the future of the food industry? A third of food produced globally is thrown out, but an article in Forbes explores a promising solution — more companies are using fermentation as a way to decrease food waste.

A new Danish startup, Resauce, gives companies the resources to turn their food waste into fermented products. Their success stories include a farmer who made fermented onion paste and sauerkraut from excess onions and cabbages, and a vineyard owner who converted grapes into a honey-fermented grape syrup. Each producer then sold their product under their own brand.

Resauce founder Philip Bindesbøll said: “Now we can give companies an innovative product, financial benefits, as well as a positive sustainable story.”

Read more (Forbes)

- Published in Food & Flavor

Ugly Delicious

A unique business practice has been developed in Montana by Farmented Foods — the company ferments discarded produce from local growers to fill their jars with the likes of radish kimchi, dill sauerkraut and spicy carrot chips. The co-owners (Vanessa Walsten and Vanessa Williamson) met in 2016 at a Farm to Market class at Montana State University. They are currently getting ready to renovate a former cafe into a fermentation kitchen, thanks to a grant from the Montana Agriculture Development Council.

“Every year, so much produce is wasted because we don’t deem it perfect enough,” says Williamson, adding that the company “was founded initially to help farmers eliminate unnecessary food loss on their farms in the form of ugly and excess crops.”

They estimate they’ve saved over 6,000 pounds of imperfect produce.

Read more (Daily Inter Lake)

- Published in Business

Fermented Foods Fighting Food Insecurity

Fermenti Foods has teamed up with a local salt producer to help food insecurity in their local county of Madison County, North Carolina.

Meg Chamberlain (pictured) donates jars of her fermented kraut and carrots to the Beacon of Hope Food Bank. She’s also helped the food bank preserve fresh food donations. And now she’s adding recipes for sauerkraut and tutorials on YouTube. Chamberlain says fermentation is a useful tool for home preservation.

“In addition to the fact that more people are growing, they need to know what to do with what they’re growing in their gardens,” she said.

Read more (Citizen Times)