Farming with Beer Waste

In a study published in Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, researchers detail how they have created an eco-friendly pesticide using beer bagasse (spent beer grains), rapeseed cake (byproduct of oil extraction from seeds) and fresh cow manure.

Chemical pesticides have been proven harmful to the environment, damaging soil and water. Pesticides are also easily consumed, and many studies link their use to multiple diseases and birth defects. Researchers from the Neiker Basque Institute for Agricultural Research and Development in Spain hope that farmers will use these organic byproducts from beer production to kill parasites, preserve healthy soil and increase crop yields.

Read more (Frontiers Science News)

- Published in Science

Best Practices for Cash Flow Management

Running a food or drink business is challenging in today’s market — there’s increasing competition, fast-paced trends and challenging access to retailers. If you run a fermentation-based business with a long production cycle, those market forces are compounded.

“A lot of businesses in this sector are in it because of the passion, they love what they’re doing, and sometimes the finances can feel very mysterious, there’s an aversion to dealing with it, and they aren’t taking the time to really look and understand the numbers,” says Maria Pearman, a principal with Perkins & Co., Portland, OR-based professionals in food and beverage finance and accounting. She shared her expertise during a TFA webinar, Best Practices for Cash Flow Management.

“Cash flow forecasting, it’s not rocket science. It’s not hard stuff. It is just very foreign to a lot of people and they avoid it,” Pearman says.

Matt Hately, a TFA Advisory Board member who moderated the webinar, agreed. Hately is an investor and advisor in fermented food and beverage brands.

“Managing cash…I would argue that it’s even more of a challenge for fermentation companies where your production cycles aren’t instant, they might take a week or three weeks or six weeks and, when you’re starting, your suppliers are probably demanding to be paid up front, your customers want 30-day terms,” he says .

Fermented Financials

Pearman, author of the book Small Brewery Finance, shared an overview on cash management. Fermentation businesses need to closely manage their cash conversion cycle as production cycles lengthen. The cash flow conversion cycle is the period between when money is spent to purchase ingredients to when payment is received from the sale of the final product.

Fermented products — which can take anywhere from a few weeks to even years to ferment — have a long cycle.

Pearman shared the example of a whisky distiller. After fermentation, whisky ages in barrels for years. All the while — before the product is ever sold — there are ongoing overhead costs for the distillery, like rent, utilities and staff.

“The rhythm of your cash flow is not going to match the rhythm of your income, and cash flow management is about bridging that gap,” Pearman says.

Cash Flow Forecasting

There are three primary financial reports that make up a business’ financial statements:

- Balance sheet (snapshot of the status of a company at a moment in time)

- Income statement (performance over a period of time)

- Statements of cash flows (sources and uses of cash over a period of time)

Often overlooked is cash flow forecasting, the expected inflow and outflow of cash over future periods.

The cash flow forecast, Pearman notes, is not standard in business financial records. It is usually kept outside of an accounting system as it’s information management generally uses. It’s important because a business can’t rely on just their income statement or bank balance to manage cash flow — labor, overhead and cost of inventory must be part of the expenses. She compared managing cash without a cash flow forecast to “building a house without a hammer.”

“One of the biggest pitfalls that I see with businesses is chasing profitability instead of cash flow,” Pearman says. “It is completely understandable because we’re all hardwired to try to do things as efficiently as we can, get the best deal, but truly in the early stages of a company, it’s way more important to manage cash flow than profitability.”

“It’s a high cost for bringing a new product to market. Cash flow issues are going to be prevalent regardless of where you are in your life cycle, and the best way to guard against cash issues is to have a cash flow forecast.”

During the webinar, Pearman shared a detailed look at a sample business’ financial workbook. She noted that it seems arduous to manage that level of detail but, without it, “you’re really flying blind.”

“It will force you to be highly in tune with the rhythms of your business,” she continues. “It will force you to learn it at such a level that it starts to become innate knowledge, you know it like the back of your hand and there’s no shortcut to that.”

View Pearman’s video presentation, companion presentation and companion spreadsheet.

- Published in Business

A Yeast Primer

Brewers, winemakers and cidermakers are continually on the hunt for the ideal flavor profiles for their fermented beverages. And the key to manipulating those flavors is yeast.

“With beer, you’re taking this kind of gross, bitter soup of sweet barley and hops, and the yeast makes it taste good. Depending on the yeast that gets put in it, it can make it taste like 400 different things, so there’s so much potential there. I think that’s really exciting,” says Richard Preiss of Escarpment Laboratories. Priess was joined by Doug Checknita from Blind Enthusiasm Brewing and Patrick Rue from Erosion Wine Co. to discuss the world of yeast in TFA webinar, A Yeast Primer.

“If you’re invested in vegetable fermentation, yeast might be sort of clouded in mystery and something that is unwanted,” says Matt Hately, TFA advisory board member who moderated the webinar. “It’s what you live by in beverage fermentation in wine and beer and it’s the key to unlocking flavors to make that magic happen.”

Domesticated vs. Wild Yeasts

Just as dogs and cats were domesticated by humans, yeasts have been as well, says Priess, whose company makes and banks yeasts. They are microscopic organisms that adapt, “so if someone’s making beer for over the span of hundreds or thousands of years then the yeast is going to change to kind of get better at fermenting that beer and maybe it’s not going to be so good at surviving out in the wild, just like our toy poodle versus our wolf.”

Other fermented drinks, like wine, sake and cider, use different yeasts with their own specific sets of traits. This is why a wine yeast can’t be used in a beer and vice versa, “though there are some opportunities to experiment.”

Fermenting with wild yeasts has become increasingly in vogue with beer brewers. Aspirational brewers are finding yeasts on the skin of fruit or the bark of trees.

The panelists on the webinar praise experimentation, but note there is risk. Priess says yeasts designed to survive in the wild can be challenging to use in a beer. Checknita points out the safety factor in using yeasts directly from nature as well, “you can get stuff that’s harmful to human health so you have to be careful with your pH levels and what controls there are.”

Traditional winemakers, on the other hand, have long used the wild yeast on grapes to ferment. Rue notes that 10 years ago winemakers began to deviate from this tradition to use pure cultures instead. This process is how many large-scale, industrial producers operate today. But smaller winemakers, who often want to emphasize the specific traits of their terroir, generally use native yeasts and traditional winemaking techniques.

“It’s amazing how wine is how God intended wine to be made because you let nature happen and you’ll probably have a pretty good result with natural fermentation,” Rue continues, “where beer, it’s very touch-and-go, you have to have the perfect conditions and I’ve been able to do spontaneous fermentation with those yeasts.”

The Yeast Family Tree

There’s a large and continually-growing family tree of yeasts, with branches forming for genetic diversity and specialization.

Priess sees three new trends emerging in yeasts: traditional yeasts (like Norwegian kveik) being rediscovered, yeast hybridization (similar to cross-breeding a tomato) and genetic engineering to enhance certain traits of yeast.

“That’s the exciting part of what we’re doing is no one really knows the best approaches to using beer yeast yet, but there’s a lot more new science that’s happening, a lot more brewers that are experimenting, and together we’re collaborating to understand how to work with yeast better and kind of unlock new flavors and new possibilities,” Priess says.

Checknita agrees. He says new yeasts are forming new family trees through spontaneous fermentation, which is taking the base of a beer and experimenting to “push and change those yeasts to do what we want and get that clean flavor that’ll make a beer that tastes good to the human palate.”

- Published in Food & Flavor

Egypt’s 5,000-year-old Brewery

Archaeologists from NYU and Princeton have uncovered the world’s oldest industrial-sized brewery. Located in southern Egypt near the Abydos ruins, the facility dates from 3000 B.C. Many of Egypt’s early kings were born in Abydos, so it’s assumed the brewery made ceremonial beer for ritual offerings and royal funerals.

“The fundamental significance of the Abydos brewery is its scale relative to anything else in early Egypt,” project co-leader Dr. Matthew Adams said. The brewery likely produced about 22,400 liters with each batch (possibly weekly.) “That is a huge amount of beer by any standard, even in modern terms. It’s absolutely unique.”

Read more (Wine Spectator)

- Published in Science

Wild Yeasts & Sour Beer

As sour beer becomes more popular, more producers are foregoing traditional kettle-sourcing processes to inoculate their brews with wild yeasts, often found in unusual places. Pennsylvania-based Levante Brewing Co. has developed a yeast called Philly Sour, which was found on the bark of a dogwood tree in a local cemetery and is now sold worldwide.

“I don’t know if the enthusiasm for hops will ever really wane, but with so many beer options available, there is definitely the space for some breweries to focus more on other ingredients,” said Gerard Olson, owner of Forest & Main Brewing Co. in Ambler, PA. That brewery every spring forages for yeasts from flowers on the property and uses them for that season’s saisons.

The Philadelphia Inquirer calls Philly Sour (and Norwegian yeast called kveik) “beer’s mostly unsung heroes.” The professor who isolated the Philly Sour yeast, “sends students into the neighborhood with Ziploc bags to collect samples, leaves, scrapings from bark, and other materials that might have yeast on them. Those materials are tested for fermentation.”

Read more (The Philadelphia Inquirer)

- Published in Food & Flavor

Chocolate’s Beer Roots

Chocolate beer sounds like a faddish flavor, but its roots run deep. Pre-Columbian Mesoamericans fermented cacao fruit to make a beer-like drink called chicha.

“Chicha is usually made from corn, but there are regional variations made from other new-world plants like potatoes, peanuts and cacao beans,” reads an article from The Seattle Times. Chicha was studied by archaeology professors at Cornell and Berkeley who found “The roots of the modern chocolate industry can be traced back to this primitive fermented drink.”

Read more (The Seattle Times)

New FDA Requirements for Fermented Food

By August, any manufacturer labeling their fermented or hydrolyzed foods or ingredients “gluten-free” must prove that they contain no gluten, have never been through a process to remove gluten, all gluten cross-contact has been eliminated and there are measures in place to prevent gluten contamination in production.

The FDA list includes these foods: cheese, yogurt, vinegar, sauerkraut, pickles, green olives, beers, wine and hydrolyzed plant proteins. This category would also include food derived from fermented or hydrolyzed ingredients, such as chocolate made from fermented cocoa beans or a snack using olives.

Read more (JD Supra Legal News)

New Trend: Performance Beer

Inspired by the beer tents popular at the finish line of high-endurance events like marathons and triathlons, creative breweries are adding electrolytes to beer. They are turning alcohol into a hydrating drink, but still giving drinkers a buzz.

The market is small, constituting just 1% of the craft beer market (and craft is just 13% of the total beer market). But performance beer is selling well with consumers wanting alcohol with fewer calories.

Read more (Bloomberg)

- Published in Food & Flavor

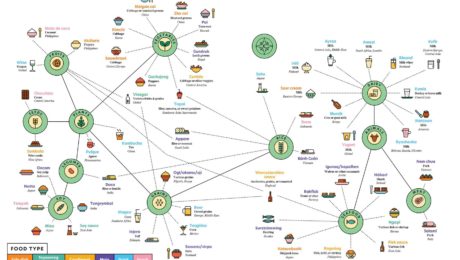

The World of Fermented Foods

In the latest issue of Popular Science, a creative infographic illustrates “the wonderful world of fermented foods on one delicious chart.” It represents “a sampling of the treats our species brines, brews, cures, and cultures around the world,” and is particularly interesting as it shows mainstream media catching on to fermentation’s renaissance. Fermentation fit with the issue’s theme of transformation in the wake of the pandemic.

Read more (Popular Science)

- Published in Food & Flavor

Launching a Fermented Brand

One of the biggest hurdles in the food and beverage industry is getting a product to market — an even bigger challenge for fermented food and drink brands featuring live bacteria.

“Fermented foods in general are still relatively new in the commercial marketplace. When we started, most beer distributors knew nothing about it. And that’s still a big challenge, how to communicate what you have. What is a fermented food? Why should people care about it?” says Joshua Rood, co-founder and CEO of Dr Hops Real Hard Kombucha. Rood shared his advice during a TFA webinar, Launching a Fermented Brand.

Rood officially began Dr Hops in 2015 with co-founder Tommy Weaver. They met in a yoga class, and turned their passion for health and great hops into a kombucha beer they started brewing in Rood’s kitchen.

At the time, there was a lot of variety and craft beer and kombucha, but hard kombucha was unheard of. “You don’t have a lot of focus on health in alcohol,” Rood says.

Rood went to investors with a pitch deck that outlined why traditional alcohol products don’t appeal to a health-conscious consumer — craft beer is made with gluten, cider is high in sugar and hard alcohol is too strong for regular use. Dr Hops, meanwhile, is gluten-free, low in sugar, unfiltered, made with organic ingredients and full of active probiotics.

“We have a passion for creating more delightful, health-conscious alcohol, and really pushing the envelope with that,” Rood says. “One of our biggest challenges is still how to communicate that into a very tiny amount of time to consumers, retailers and distributors.”

Starting in a category that didn’t yet exist, figuring out licensing took years. Dr Hops began with $13,000 raised from a Kickstarter campaign, then crowdsourced another $10,000 the following year. By 2017 — with labelling, alcohol licensing and product stability figured out — investors pledged $115,000, enough to start small-scale commercial production. Dr Hops officially went to market in 2018, self-distributing and selling at street fairs and beer festivals.

“Part of the key to selling stuff without a huge marketing budget is focus,” says Alex Lewin, webinar moderator, Dr Hops advisor and TFA Advisory Board member. “Dr Hops started in the Bay Area, and won over relationships we had with some retailers — we had some real advocates. Don’t do a national launch if you have no budget.”

Rood stresses education is a key piece of marketing for the fermentation category.

“How much is the whole community speaking about and educating the world about and celebrating the value of live fermented foods? The more we’re all doing that, the more it works to sell these products,” he adds.

Test audiences, consumer feedback and word-of-mouth marketing have been key to Dr Hops success.

“The fact that we were able to grow our business almost three times in 2020 even in the pandemic with no marketing is one of the best things we have to say about what we have. People want this,” Rood says.

Highlighting strengths helps Dr Hops distinguish itself in a newly-competitive field of hard kombucha brands. Dr Hops’ product line includes flavors that compare to well-known alcohol beverages. Their Kombucha Rose flavor is a substitute for wine, Ginger Lime for a cocktail, Kombucha IPA for beer and Strawberry Lemon for a mimosa.

“While people might not understand hard kombucha, they pretty much already have a preference between beer, wine, cocktail and champagne or spritzers,” Rood says.

Health is core to Dr Hops, but higher-alcohol drinks are also higher in calories. Seltzer has been a key competitor to hard kombucha because seltzer’s calories are low.

“But it’s not interesting,” Rood says. “If you really love alcohol or food or beverage in general, you want something more interesting than that. At this point, we’re willing to gamble on enough people who care about transparency and authenticity that if we put the nutrition label on there and list all the ingredients, even if it doesn’t compare very well on a calorie level, there’s enough else to it that people are going to try it.”

- Published in Business