Local Flavors Drive Singapore’s Growing Craft Cocktail Scene

Fifteen years ago, Singapore’s craft cocktail scene was nonexistent. The few existing cocktail bars served beer and whisky. Today, Singapore is filled with world-class venues serving unique drinks that highlight the regional ingredients and culture of the southeast Asian metropolis.

The National Geographic explores “the city-state’s roster of award-winning drinking dens includes stellar hotel bars, sleek speakeasies and reimagined Chinatown shophouses.”

Creative drinks include those served by Nutmeg & Clove. Its Singapore-inspired cocktail list features a changing bar menu, like the current cocktail Can Bubble Gum?, a mezcal-based drink topped with candy-flavored foam. The drink is a tongue-in-cheek jab at Singapore’s ban on chewing gum. Another unique cocktail, the Oyster Omelette, is served at bar Native. The yellow, umami-packed drink is made with a base of distillate of oysters harvested off a nearby island, Pulau Ubin. The drink is served, appropriately, in a cup made of oyster shells.

“When we opened eight years ago, there were a few cocktail bars in Singapore, but they were mainly quite international,” says Colin Chia, owner of Nutmeg & Clove. “I wanted to set up something that we could proudly call a Singaporean cocktail bar.”

While sourcing can be a challenge in Singapore – an island off southern Malaysia – bars get creative. Menus are seasonal, ingredients are local and often cured, pickled or fermented to extend shelf life. Pictured, Yugnes Susela, the owner and bartender of The Elephant Room, that focuses the establishment on the colorful markets of Singapore enclave Little India. The drink is the Peranakan cocktail at Native Bar.

Read more (National Geographic)

- Published in Food & Flavor

The Flavor Whisperer on Fermentation

Flavor is much more complex than just taste. Flavor can be collected, extracted, infused, created and transformed. And, in a billion-dollar flavor industry devoted to putting flavors into processed foods, fermentation is the oldest and most natural flavor creator, developing new flavors at a molecular level.

“Fermentation as a flavor creation process in collaboration with microbes, there’s almost no limit to how you can apply it and use the ingredients around you and have a more flavorful palette to work from,” says Arielle Johnson, PhD, a flavor scientist, gastronomy and innovation researcher and co-founder of the Noma Fermentation Lab.

A food chemist dubbed the flavor whisperer, she works with restaurants on innovating dishes and cocktails. She researches how flavor is perceived and is writing a book on her studies, Flavorama. Her work comes together in “all things science and cuisine have to say to each other.”

This week Johnson shared her insights into flavor and fermentation as a guest lecturer at Harvard University’s Science & Cooking series.

Taste & Smell Receptors

Flavor can be quite complex – Johnson calls it a black box.

There are five primary tastes: sweet, sour, salty, umami and bitter. Each taste evolved to ensure humans get basic nutrition. We use sweet foods for the energy in sugar, sour ones for vitamin C from fruit and fermented foods. Salty foods provide the essential mineral sodium. We seek umami foods for the taste of glutamine, an amino acid in proteins and fermented foods.

But bitter, Johnson points out, doesn’t sense one thing. It senses multiple molecules that are potential toxins for us. This is why bitter is called an acquired taste.

Smell is Johnson’s favorite part of the flavor profile. In order to taste, we must smell, too. Molecules land in the olfactory receptors in the nasal cavity and help activate taste. This is why food is tasteless if you plug your nose while eating. But the back of the throat is also connected to the nasal cavity, so the throat becomes “the secret backdoor” for sensing flavor.

While there are five major tastes and four receptor areas on the tongue, there are 40 billion smellable molecules and 400 receptors for smell.

Supertasters vs. Nontasters

Taste and smell, she detailed, help us understand how fermentation works.

The population can be divided into supertasters or nontasters. During her presentation, Johnson had the audience put a strip of filter paper on their tongue. The paper included a harmless bitter molecule phenylthiourea (PTC), but only roughly half the class could taste it. This group are supertasters – the group who could not taste the PTC are nontasters.

She explained everyone has different density of their taste buds. Supertasters have more taste buds, so more taste receptors signals are sent to their brains. This has culinary implications. Because their sense of taste is more sensitive, flavors are intense and supertasters have a less adventurous palette. Meanwhile nontasters have dulled senses, so it takes a lot of flavor to activate taste.

“The good news for supertasters is that fermentation is usually salty and sour and often umami – all of which counteract bitterness,” Johnson says. “Fermentation is a way to create new flavors but also transform ingredients.”

Fermentation as Flavor

Though “microbes are opportunistic” and pop up in foods whether planned or not, fermentation can’t be forced, Johnson says. When making a sauerkraut, for example, microbes don’t need to be added. Fermentation works with what’s on the surface of the cabbage and on the producer’s hands.

Salt is key in fermentation as a flavor additive, a preservation element and a safety measure. Salt filters out bad molds and avoids letting a ferment spoil. Other factors “dial in the flavors in this molecular flavor creation process,” she says, like the correct ingredients, temperature control and humidity.

“We’re really excited about microbes and fermentation,” Johnson says. “In this process of this exponential growth that microbes do, they’re eating things, they’re getting energy, but they’re also running their regulator metabolism. So there’s all these waste products that are not very significant to the microbes, but that can create a lot of interesting flavor complexity.”

- Published in Food & Flavor, Science

Fermented Flavor Development in Restaurants

In the last decade, fermentation has taken center stage at fine dining restaurants. How do owners and chefs develop and maintain a fermentation program for their kitchen?

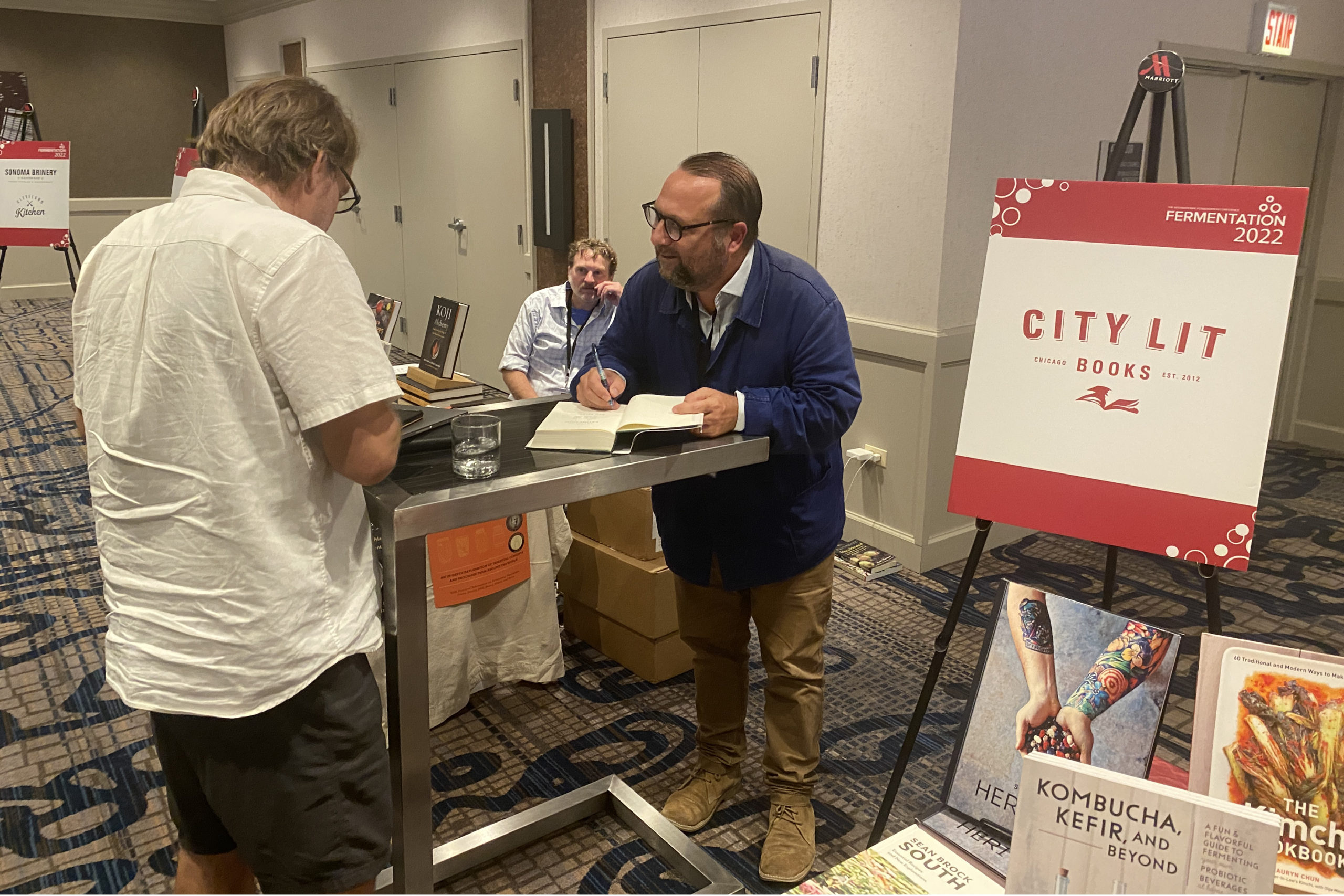

An all-star team of U.S. chef-owners at FERMENTATION 2022 shared their successes and failures in developing fermentation-focused kitchens. Speakers included: Sean Brock of Audrey Restaurant in Nashville, Jeremy Kean of Brassica Kitchen in Boston and Misti Norris of Petra & the Beast in Dallas. Jori Jayne Emde, chef, educator and owner of Corner Office in Taos, New Mexico, moderated the discussion.

The chefs all focus on whole food utilization, aiming to eliminate food waste in flavor-packed dishes. Fermentation is key. Food scraps that would otherwise be thrown out – stems from produce, coffee grounds or animal bits – are fermented and reinvented in flavorful, unique dishes.

“By reusing the product in different manipulations over and over again, this type of program can really develop branding potential over time,” Emde says. “The process of bringing several lives to one product puts one’s fingerprint on the cuisine, so the restaurant expresses its own terroir.”

In-House Fermentation

Core to developing a restaurant fermentation program is assigning someone to oversee the process. Who will track the start dates, monitor pH levels and control filtration?

Emde, who formerly ran Fish & Game in New York’s Hudson Valley, quickly learned at the restaurant “you can’t just have a multitude of chefs handling it…ferments are alive and require being nurtured and cared for.”

Brock agrees, noting some restaurants have their chef de cuisine or sous-chef head up fermentation efforts. “But the reality is they have so much to do already.”

“It’s critical to have someone dedicated to the program,” Brock says. “When you’re having to build such a renegade operation, the biggest challenges are keeping up with inventory and monitoring each ferment.”

Audrey hired a fermentation specialist in 2014, Elliot Silber. He has a chemistry degree and “understands fermentation at a completely different level,” Brock says.

“I still can’t believe we have someone in charge of fermentation,” he adds. “Now, we put fewer things on the plate with a bigger impact. I get to finally produce food I would consider minimalist.”

Brassica Kitchen takes a different approach to their fermentation program – a food map.

“We’ve been running fermentation forward cuisine for about 10 years and, in that 10 years, we’ve gone through a lot failure and chaos and really kind of developing things as we go, to changing the menu everyday to coming in long before service to staying long after to doing inventory and plug and play with them. We hit a wall,” Kean says. “We’ve found ourselves looking at over 100 misos and going ‘What the fuck do we do with this?’”

The kitchen’s food map is a shared document where the chefs outline how to utilize every byproduct. It’s been Brassica’s most effective menu-planning solution. “This food map has solved a lot of the problems and created a box of creativity we can really thrive in,” Kean says.

Health Department Woes

When Brock launched his first fermentation program at Charleston’s Husk restaurant in 2010, “ironically our biggest challenge was the health department,” Brock said. “They would make us throw food away.”

Health department officials – many who had no idea what fermentation was or its inherent safety – would immediately issue violations for any food sitting on a counter at room temperature, a normal process for fermenting foods or beverages. Husk maintained a makeshift lab on the roof of the restaurant hidden from officials, and staff had a code word for when the health department would come to the restaurant.

Norris recalled instances where inspectors would pour bleach on their fermented food products or throw their meat in the trash.

“It’s hard because we’ve taken the time to learn and be knowledgeable about how to keep these foods safe. And then someone comes in who is supposed to be keeping people safe but has no knowledge of food and we’re trying to make food healthier and keep it more dynamic and sustainable,” Norris says. “It’s frustrating when you put so much of yourself and your philogosphy into the food.”

Audience Acceptance

Today – as fermentation is featured regularly in food, health and science news – diners are eager to eat unique, fermented dishes. This hasn’t always been the case. Even today,diners need to trust a restaurant before they will buy dishes experimenting with fermentation. Norris notes, when Petra and the Beast first opened, fermentation was not a food trend in Texas. Residents had not grown up with a food culture of eating and preserving wild food.

“It definitely did not happen overnight,” she says. “It took a lot of educating and reassuring people that these things are delicious and they are a little uncommon, a little different. It’s something that took time and effort to understand what we were doing with full utilization and sustainability.”

Kean, too, said it took time at Brassica.

“We’d be using all these (fermented) products and I wouldn’t even mention it on the menus,” he said. “The trust was built over all these years and until we could really start speaking on it.”

Eliminating food waste was mentioned as fermentation’s gateway of acceptance for diners.

Food Waste into Food

Brock says the goal at Audrey is to find 10 uses for every seasonal, region-specific ingredient. For example, last year they received candy roaster squash from a local farm and served it in different forms in dishes throughout the fall season. But they also fermented it and will be serving it again this year.

“We don’t create dishes and then get the ingredients,” Brock says, “the ingredient fuels the dish.”

The kitchen at Audrey is full of glass-encased ferments, each organized by parts of the tongue.

Brassica has found success in utilizing food waste by creating delicious dishes that are “black holes for the extra stuff” Kean says. For example, they serve a fried rice dish using sticky rice from the day before with fermented vegetables. The dish is popular, low cost and “encourages little things that can be vehicles in a dish.”

“It’s been inspiring over the years to find a use for the byproducts, then the byproducts become so important that you have to then buy the byproduct,” he says. “It’s happened to us over and over again.”

Petra and the Beast focuses on whole animal utilization. By being sustainable and “hyper-seasonal,” Norris says, Petra is “creating food with the most depth, creating food that’s not just one note.”

“I ask myself and the team ‘Well, what should we do with it? Is there a better use for it? Is there a sour brine or can we make a salt out of it and use it on that same vegetable next season?’” Norris says. “If you really truly understand why a flavor profile is developing in a certain way, you look at everything else differently.”

- Published in Food & Flavor

Chefs Turn to Fish Sauce for Flavor Punch

Fish sauce has been used for centuries as a umami “flavor bomb” for dishes. An article in British Post Magazine highlights how chefs throughout the world use regional variations of fish sauce – from Vietnamese nuoc mam, Malaysian belacan, Filipino bagoong and Italian colatura.

“Fermentation has been an integral part of many traditional food cultures to develop flavourful foodstuffs,” says Ana San Gabriel, who specializes in umami taste receptors and physiology at food and biotech company Ajinomoto.

San Gabriel details that fish sauce is made from the proteins (myosin, troponin and titin) from the flesh of fish that are broken into umami compounds (peptides and free glutamate) through salting and fermentation.

Belacan is a staple of Malaysia’s coastal cuisine. It’s a shrimp paste used in curries and sambals.

“Belacan has a deep history and heritage in Malaysia, and for many locals it evokes fond memories of family gathered together to make it from scratch,” says Jasper Chow, the executive sous chef at One&Only Desaru Coast, a luxury beachfront resort in Malaysia. “Making belacan is a delicate process that reminds us of the simple yet sophisticated methods of cooking that survive even until today.”

In Vietnam, nuoc mam is made in the southern island of Phu Quoc. It can be made from fish, shrimp or crab.

“As a dip, it highlights the sweetness and clears the greasiness of meat and deep-fried bites. It gives an exciting flavor to, yet never buries, the beautiful natural taste of fresh rolls,” says Pham Van Nhuong, the sous chef in the kitchen at Vietnam’s Tempus Fugit. “As a seasoning, unlike salt, it adds to braises, stews and even stir-fries a vigorous flavor and a signature scent.”

Bagoong in the Philippines is made from fish or krill.

“Bagoong is one of the building blocks of umami, or linamnam, in Philippine cuisine. Sometimes it’s used as a condiment or flavor for an existing dish, sometimes it will be the actual component or basic building block of a dish – like the dish binagoongan, which literally means ‘you used bagoong’,” says chef Jordy Navarra, chef at Toyo in Manila.

Colatura di alici is Italy’s modern version of garum, made from salted and fermented anchovies along Italy’s Amalfi Coast.

“We use colatura as a subtle addition to many dishes and in doing so have nearly completely removed the use of sea salt for sauces and purées,” says Antimo Maria Merone (pictured), chef at Neapolitan restaurant Estro in Hong Kong. “This allows us to precisely reach the level of sapidity by adding a certain percentage of fish sauce to the preparations that lack natural umami.”

Read more (Post Magazine)

- Published in Food & Flavor

Mexican Hard Cider

An Oregon cidery is taking an interesting approach to hard cider, ciders inspired by aguas frescas.

La Familia Cider Company founder José Gonzales is a first-generation Mexican-American. He runs La Familia Cider Company with his wife, Shani, and their kids Jay Jay and Jezzelle. José and Shani grew up drinking aguas frescas, but couldn’t find those drinks in Oregon.

“As my wife and I were enjoying Oregon craft beer and cider, she said, ‘Too bad there aren’t any of the flavors we grew up with,” José said. So they developed their own brand with flavors reflecting their heritage.

Their ciders are from freshly-picked, northwest-grown apples, but the flavors reflect the family’s Mexican heritage. Mainstay flavors include Manzana, Tamarindo and Hibiscus.

“With our ciders we wanted to do something a little bit different,” explained Jay Jay. “Change up the game a little bit.”

Today, the Salem, Ore.-based brand is in more than 50 stores in Oregon and Washington.

Read more (KGW8)

- Published in Business, Food & Flavor

The New Funk

Have you tasted furu yet? More Asian American chefs are using the fermented tofu.

Common in Chinese and Taiwanese cuisine, furu is made by soaking soybean curbs in a brine of rice wine, water, salt and spices. The flavor has a “specific tang, mild sweetness and intense umami,” according to a New York Times article.

“Furu adds a ton of funk that you can’t get from anything else,” says Calvin Eng, owner of the Cantonese American restaurant Bonnie’s in Brooklyn, New York. The restaurant’s dish furu cacio e pepe mein is noodles in the fermented bean curd.

Read more (The New York Times)

- Published in Food & Flavor

Cultured in Chicago: Highlights of FERMENTATION 2022

Science met the culinary arts in Chicago, at the first in-person conference of The Fermentation Association (TFA), FERMENTATION 2022. Over 200 food and beverage professionals from 15 countries Participated in four days of programming.

“There’s no denying that fermentation is having a moment – and that’s a wonderful thing that more and more people are aware of fermentation and interested in fermentation – but it’s really important to keep saying fermentation is not a fad, fermentation is a fact,” said Sandor Katz, fermentation author and educator.

Katz was the opening keynote speaker at FERMENTATION 2022. The nearly 50 experts and thought leaders who presented included Dan Saladino (BBC journalist and author of Eating to Extinction), Kirsten Shockey (author, educator and co-founder of The Fermentation School), Bob Hutkins (food microbiology professor at University of Nebraska and founder of Synbiotic Health), Sharon Flynn (founder of The Fermentary in Melbourne, Australia), Bruce Friedrich (co-founder and executive director of The Good Food Institute), Maria Marco (food science professor at University of California, Davis) and Sean Brock (chef and owner of Nashville’s Audrey Restaurant).

The conference comes as sales of fermented foods and beverages continue to rise. Fermented products grew 7.1% in the last year, according to SPINS LLC, a data provider for natural, organic and specialty products that also presented at FERMENTATION 2022.

Though Katz taught his first fermentation workshop in 1998, he’s seen “a building interest in fermentation” in the last decade. Each year since 2011, “someone says the food trend of the year is fermentation.”

“Usually I end up being a cheerleader for fermentation, encouraging people who somehow think that fermentation is an alien process, that there’s something scary about it,” he said. “I mostly reassure people that they’ve been eating products of fermentation almost every day for their entire lives, that these are processes that their safety has been proven by their endurance over time. But you all don’t need to hear that. I am speaking to the converted here.”

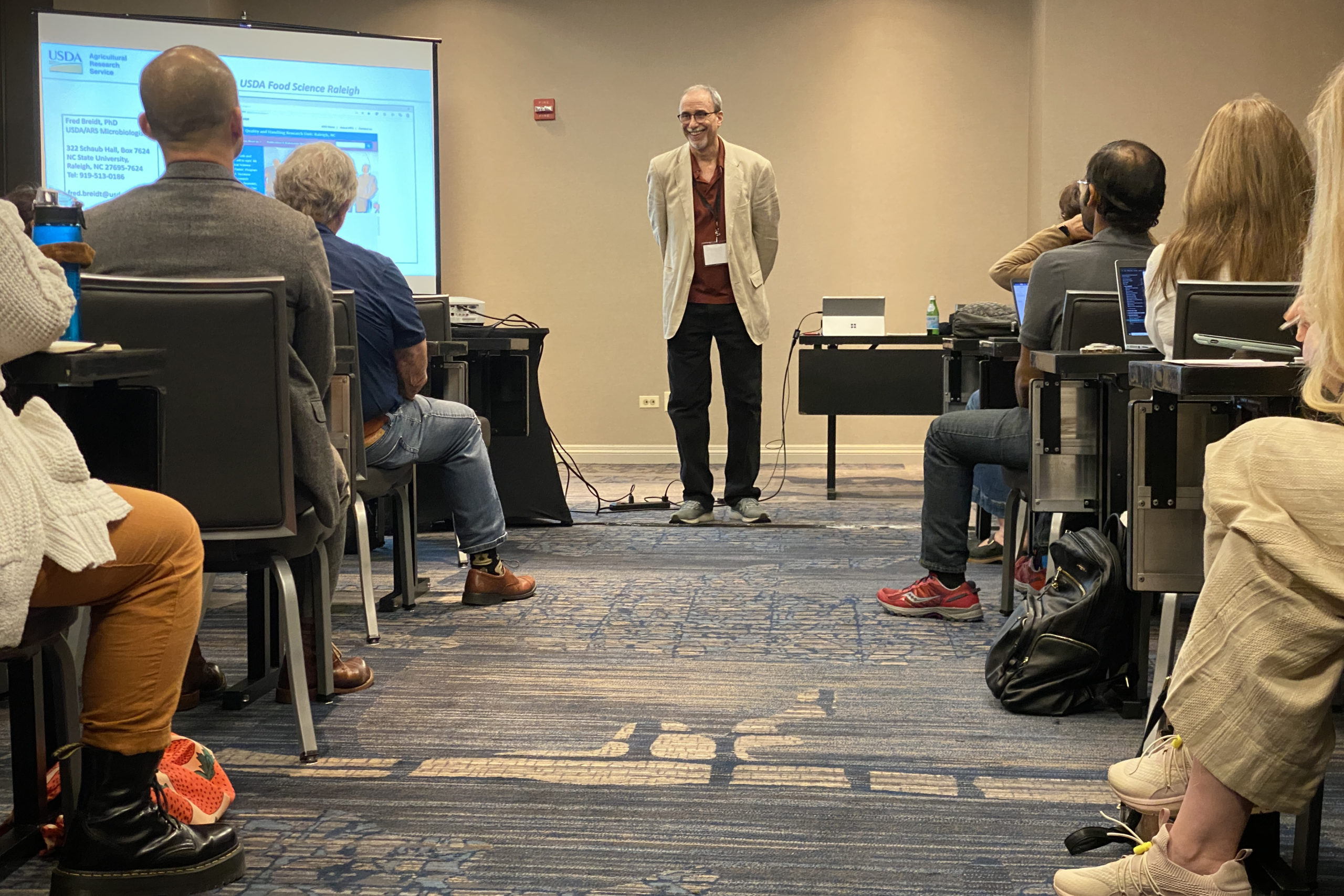

Where Science Meets Industry

TFA aims to fill a niche in the world of fermentation. There are plenty of DIY fermentation festivals, food and beverage industry conferences and trade shows. But TFA connects science and industry.

Attendees at the event included an array of professionals involved in fermentation – producers, retailers, chefs, scientists, researchers, authors, suppliers, educators and regulators. The conference revolved around three tracks: food, flavor and culture; science and health; and business, legal and regulatory. The group of passionate fermenters in attendance uniformly expressed their excitement and delight to learn from experts in different disciplines.

“This unique conference had the most diverse attendees as it included chefs, scientists and more,” said Glory Bui, a graduate student researcher at the University of California, Davis. “It was nice to network with those who were and were not in academia to hear different perspectives in the fermentation industry.” [Bui won the student poster competition with her research on how fermented dairy products can affect gastrointestinal health.]

Producers made up over 40% of attendees and ran the gamut from small to large scale. Sash Sunday, founder and fermentationist behind OlyKraut in Olympia, Wash., said she’s been searching for such a fermentation conference since starting her brand in 2008.

“I really appreciate getting to spend time getting to know other fermenters, hearing about people’s creative processes and experiences in the field,” Sunday said. “I really loved all the tastings and spending time with people who really think about the flavors in fermented foods.”

Niccolo Fraschetti, owner of Alive Ferments, said networking was one of his favorite parts of the conference.

“There were people there that were superstars of fermentation to people making kimchi in the bathtub,” Fraschetti said. “It was such a cool merging of fermentation.”

Fraschetti officially launched Alive Ferments in March and said he never expected the brand to grow so fast, so quickly. Alive Ferments currently is sold in 25 stores in the San Diego area. At FERMENTATION 2022, he brainstormed ideas with attendees and speakers.

“Usually I feel like in these situations, everyone is tight-lipped and doesn’t want to share (business secrets),” he said. “But everyone was a really embracing community and willing to share their knowledge. There was no competition between the peers that were at the conference.”

Connecting with others in the industry was a highlight, too, for Suzette Smith, founder of Garden Goddess Ferments and Pick up the Beet in Arizona.

“I loved that like minds were able to come together sharing similar passions,” Smith said. (I also loved “learning what’s new in the promotion of fermented foods.”

Gregory Smith, an independent chef based in Pittsburgh, said he “drove back from Chicago with my mind racing about all the things I learned.” He said the various chefs who spoke at the conference – like Flynn, Brock, Ismail Samad of Wake Robin Foods, Jessica Alonzo of Native Ferments, Misti Norris of Petra and the Beast and Jeremy Kean of Brassica Kitchen – inspired him to dive into upcycling.

“I’m excited about the way they made me look at food waste in the kitchen space and how to help utilize waste and taking excess product and converting it into something tasty,” said Smith, who runs his independent culinary service Thyme, Love & Culture with friend Romeo Kihumbu.

Karen Wang Diggs, founder of the ChouAmi fermentation device, spoke at the event in a session on fermenting with medicinal plants. She said it was “an honor” to speak at FERMENTATION 2022.

“I got to hang out with a bunch of really cool, ‘cultured,’ fermenting people – and the presentations were fabulous,” she said.

Added Neal Vitale, executive director of The Fermentation Association: “It was a privilege to have a stellar lineup of speakers. It was great to get to get together at last and explore so many aspects of fermentation.”

Focus on Food

Other events at the conference included: a dinner with a fermentation-focused menu prepared by Rick Bayless, chef and restaurateur; a mezcal tasting with Lou Bank, founder of SACRED and the Agave Road Trip podcast; a craft beer and chocolate pairing with Long Beach Beer, Bread and Spirits Lab; a flavor analysis workshop with Sensory Spectrum Inc.; a screening of Ed Lee’s film Fermented (complete with buttered popcorn!); and multiple book signings.

Bayless, the James Beard Award winner who runs multiple Chicago restaurants, mingled with conference attendees during the dinner. He said he and his staff enjoyed the challenge of putting something fermented in every course.

“This is the first time we’ve done a meal that is so heavily fermented,” he said, “and we had a lot of fun doing it.”

Courses included a fermented corn masa tamal, beed with a fermented black bean sauce made with black bean miso and Oaxacan pasilla chile, smoked yellowfin tuna in a broth of tejuino (fermented corn drink), and chocolate from Tabasco, Mexico, with tepache (fermented pineapple) sorbet .

“I was at a conference with Sandor Katz years ago and I talked to him about making black bean miso, and now I get to serve it to him,” Bayless said.

The Fermentation Association was started in 2017 as the brainchild ofJohn Gray, then the owner of Bubbies Pickles. His goal was simple – to bring together everyone in the world of fermentation. Today, TFA circulates its biweekly newsletter to nearly 14,000, is followed by over 11,000 on Instagram and will next develop its presence on LinkedIn. The Association is run by a small staff and a 22-member Advisory Board, including six Science Advisors.

FERMENTATION 2022 was originally planned to be a May 2020 event, but obviously postponed due to Covid-19. A virtual FERMENTATION 2021 was held in November 2021. TFA will announce plans for 2023 and beyond in the coming months.

- Published in Business, Food & Flavor, Health, Science

Endangered Fermented Foods

Through selective breeding and domestication of plants and livestock, the world’s food system has lost diversity to an alarming degree. Crops are monocultures and animals are single species. Journalist and author Dan Saladino argues it’s vital to the health of humanity and our planet to save these traditional foods.

“There’s an incredible amount of homogenization taking place in the last century, which has resulted in a huge amount of concentration of power in the food system but also a decline in the amount of biodiversity,” says Saladino, author of Eating to Extinction. “That agricultural and biological diversity is disappearing and it’s taken us thousands, millions of years for plant, animal evolution to get to this point.”

Saladino was a keynote speaker at The Fermentation Association’s conference FERMENTATION 2022, his first in-person talk in the United States since his book was released in February. A journalist with the BBC, Saladino was also an active participant in the event, attending multiple days’ worth of educational sessions. He called the conference “mind expanding.”

“I thought I knew about fermentation, when in fact I know very little,” Saladino said to the crowd in his keynote. “We’ve been bemused by the media reports that fermentation is a fad or fashion. What we know is that the modern food system in the last 150 years is the fad. It’s barely a blip in the context of our evolution as species, and it’s the way we’ve survived as a species over thousands of years.”

Eating to Extinction includes 40 stories of endangered foods and beverages, just touching on a fraction of what is happening around the world. To date, over 5,000 endangered items from 130 different countries have been cataloged by the Slow Food Foundation’s project the Ark of Taste.

During FERMENTATION 2022, Saladino centered his remarks around the endangered fermented foods he chronicled in his book – Salers cheese, skerpikjøt, oca, O-Higu soybeans, lambic beer, pu’erh tea, qvevri wine, perry and wild forest coffee. Here are some of the highlights of his presentation.

Salers cheese (Augergne, Central France)

Fermentation was a survival strategy for many early humans, a fact especially evident in the origins of cheesemaking. In areas like Salers in central France, villagers live in inhospitable mountain areas where it’s difficult to access food. In the spring each year, cheesemakers travel up the mountains with their cattle and live like nomads for months.

“It’s extremely laborious, hard work,” Saladino says, noting there’s only a handful of Salers cheese producers left in France. He marvels at “the ingenuity of taking animals up and out to pasture in places where the energy from the sun and from the soil is creating pastures with grasses with wildflowers and herbs and so on.”

Unlike with modern cheese, no starter cultures are used to make Salers cheese. The microbial activity is provided by the environment – the pasture, the animals and even the leftover lactic acid bacteria in the milk barrels. Because of diversity, the taste is rarely consistent, ranging season to season from mild to aggressive.

“The idea of cheesemaking is a way humans expand and explore these new territories assisted by the crucial characters in this: the microbes,” he adds. “It can be argued that cheese is one of most beautiful ways to capture the landscape of food – the microbial activity in grasses, the interaction of breeds of animals that are adapted to the landscape. It’s creating something unique to that place.”

Skerpikjøt (Faroe Islands)

Skerpikjøt “is a powerful illustration to our relationship with animals, with meat eating,” Saladino says. It is fermented mutton and unique to Denmark’s Faroe Islands. Today’s farmers selectively breed their sheep for ideal wool production, then slaughter the lambs for meat. In the Faroes, “the idea of eating lamb was a relatively new concept.” Sheep are considered vital to the farm as long as they’re still producing wool and milk.

Once a sheep dies or is killed, the mutton carcass is air-dried and fermented in a shed for 9-18 months. The resulting product is “said to be anything between Parmesan and death. It certainly has got a challenging, funky fragrance,” Saldino says.

But it contrasts traditional and modern food practices. Skerpikjøt is meant to be consumed in small quantities, delicate slivers of animal proteins used as a garnish. Contemporary meat is served in large portions and meant to be consumed quickly.

Oca (Andes, Bolivia),

In the Andes – “one of the highest, coldest and toughest places on Earth to live” – humans have relied on wild plants like oca, a tuber. After oca is harvested, it’s taken to the Pelechuco River. Holes are dug on the riverbank, then filled with water, hay and muna (Andean mint). Sacks of oca are placed in the holes, weighted down by stones, and left to ferment for a month. This process is vital as it leaches out acid.

“Through processing, this becomes an amazing food,” Saladino says.

But cities are demanding certain types of potatoes, encouraging remote villagers to plant monocultures of potatoes which are prone to diseases. The farmers end up in debt, buying fertilizers and pesticides to grow potatoes.

“For thousands of years, oca and this fermentation technique and the process to make these hockey pucks of carbohydrates and energy kept them alive in that area,” Saladino says. “It’s a diversity that is fast disappearing from the Andes.”

O-Higu soybeans (Okinawa, Japan)

The modern food industry is threatening the O-Higu soybean, too. It was an ideal soybean species – fast-growing, so it can be harvested before the rainy season and the arrival of insects.

“But by the 20th century, the soy culture pretty much disappeared,” Saladino says.

With World War II came one of America’s biggest military bases to Japan. U.S. leaders dictated what food could be planted on the island. Okinawa was self-sufficient in local soy until American soy was introduced.

Lambic Beer (Belgium)

Saldino explained that, after a spring/summer harvest, Belgian farmers became brewers. They used their leftover wheat to create brews unique to the region.

But by the 1950s and 1960s, larger brewers began buying up the smaller ones. Anheuser-Busch InBev now produces one in four beers drunk around the world.

“There [is] story after story of these distinctive, unique, small breweries disappearing as they are bought up or absorbed into this growing, expanding empire of brewing,” Saladino says. “It’s probably one of the most striking cases of corporate consolidation of a drink and food product.”

Saladino stressed not all is lost. He shared stories of scientists, researchers and local people trying to save endangered foods, collecting seeds, restoring crops and combining traditional and modern-day practices to preserve the world’s rare foods.

“There have been so many fascinating stories of science and research discussed over the last few days at this conference, and I think the existence of The Fermentation Association is exciting because it is bringing together tradition, culture, science, culinary skills, all of these things we know food is,” Saladino added. “Food is economics, politics, geography, anthropology, nutrition. What I’m arguing is that these clues or glimpses into the past for these endangered foods, they’re not just some kind of a food museum or an online catalog. They are the solutions that can help us resolve some of the biggest food challenges we have.”

- Published in Food & Flavor

Why did Americans Turn to Drinking ACV?

A deep dive on Epicurious explores how apple cider vinegar (ACV) became America’s favorite. It is popular today as a detox tonic, but has a deep history in the U.S., “intertwined with the global spread of apples and with the transformations of fermentation.”

Today, vinegar is considered an industrialized condiment but, until the 19th Century, it was homemade. Kirsten Shockey, author of Homebrewed Vinegar (and a TFA Advisory Board member) notes the key to making vinegar is nurturing the natural fermentation process. “Vinegar happens whether you want it to or not,” she says. “As soon as fruit is picked, it’s a race against time,” she adds. As the fruit ripens, wild yeasts ferment their sugars into alcohol. Microbes feast on that alcohol, converting it to acetic acid.

Paul C. Bragg, namesake of the Bragg vinegar brand, helped popularize commercial vinegar. Theirs is still a raw, unpasteurized ACV. Paul preached the benefits of vinegar as far back as in the 1970s. This support coincided with “the rise of a countercultural natural food movement, which embraced the brown, gritty and ‘all-natural’ in its refusal of the refined, bleached and heavily processed products of the industrial food system.” (Pop star Katy Perry invested in Bragg in 2019).

The article also highlights artisanal vinegar brands, like American Vinegar Works in Massachusetts and two Pennsylvania producers, Supreme and Keepwell.

Isaiah Billington cofounder of Keepwell says that making vinegar “helps us interact closely with the total landscape of local agriculture.” Vinegar also uses produce that can’t be sold because it’s too ripe, or because the apple is “very ugly.” “We work at the margins of the harvest.”

Read more (Epicurious)

- Published in Food & Flavor

Kimjang, the Act of Preparing Kimchi

As Koreans enter the autumnal kimjang season – the time of year when kimchi is prepared with fresh, seasonal vegetables – The New York Times highlights how cooks outside of Korea are preparing the dish.

“For many communities in South Korea, a kimjang (also spelled gimjang) remains a grand act. But these days, Korean cooks outside of the motherland are adapting to their individual environments accordingly, scaling down their kimjangs to fit their lives or even hosting them virtually,” writes NYT food journalist Eric Kim, author of the book Korean American: Food That Tastes Like Home. “In a world where most people buy their kimchi at the store, preserving the act of preservation has become a priority for Koreans who wish to carry on the tradition of kimjang.”

Many American Koreans have memories of making kimchi with their parents and grandparents. Two women interviewed in the article have made kimchi-making their livelihood. Lauryn Chun, founder of Mother-in-Law’s Kimchi, says “If you can make a salad, you can make kimchi.” Ji Hye Kim, chef of Miss Kim in Michigan, describes kimchi as being like a zombie – “Not quite alive, but not quite dead.”

Kimjang has been recognized as a cultural heritage and “set of living knowledge” by UNESCO since 2013. The pickled flavor and gamchil mat (meaning “savory taste” in Korean) are defining elements of kimchi.

Read more (The New York Times)

- Published in Food & Flavor