French Animal-Free Cheese

A sign that animal free, alternative proteins are gaining more traction – Even Parisians are using microbial fermentation to make dairy-less cheese. Two French startups have raised a combined $14 million to make cheese without cows.

“French cheeses are regarded as some of the best in the world,” reads an article in VegNews. “Two French startups just raised a combined total of $14 million to prove that delicious, complex, melty vegan French cheese can be made in a new way, one that removes cows from the production cycle, improving animal welfare and environmental impact while preserving all of the things people love about cheese.”

Paris-based startup Standing Ovation closed on $12 million this month. The company, founded in 2020, uses microbial fermentation to produce casein proteins that can then be added to vegetable or mineral bases to create replicas of classic French cheeses. Female-led Nutropy raised $2 million in funding for its animal-free casein that can be used in a variety of applications.

“As cheese lovers, we know the importance of cheese in our gastronomic culture and want to offer consumers a wide range of cheeses free of lactose and dietary cholesterol that are produced in an environmentally friendly and sustainable manner,” said Nathalie Rollan, Nutropy CEO.

Read more (VegNews)

- Published in Business

Cultured in Chicago: Highlights of FERMENTATION 2022

Science met the culinary arts in Chicago, at the first in-person conference of The Fermentation Association (TFA), FERMENTATION 2022. Over 200 food and beverage professionals from 15 countries Participated in four days of programming.

“There’s no denying that fermentation is having a moment – and that’s a wonderful thing that more and more people are aware of fermentation and interested in fermentation – but it’s really important to keep saying fermentation is not a fad, fermentation is a fact,” said Sandor Katz, fermentation author and educator.

Katz was the opening keynote speaker at FERMENTATION 2022. The nearly 50 experts and thought leaders who presented included Dan Saladino (BBC journalist and author of Eating to Extinction), Kirsten Shockey (author, educator and co-founder of The Fermentation School), Bob Hutkins (food microbiology professor at University of Nebraska and founder of Synbiotic Health), Sharon Flynn (founder of The Fermentary in Melbourne, Australia), Bruce Friedrich (co-founder and executive director of The Good Food Institute), Maria Marco (food science professor at University of California, Davis) and Sean Brock (chef and owner of Nashville’s Audrey Restaurant).

The conference comes as sales of fermented foods and beverages continue to rise. Fermented products grew 7.1% in the last year, according to SPINS LLC, a data provider for natural, organic and specialty products that also presented at FERMENTATION 2022.

Though Katz taught his first fermentation workshop in 1998, he’s seen “a building interest in fermentation” in the last decade. Each year since 2011, “someone says the food trend of the year is fermentation.”

“Usually I end up being a cheerleader for fermentation, encouraging people who somehow think that fermentation is an alien process, that there’s something scary about it,” he said. “I mostly reassure people that they’ve been eating products of fermentation almost every day for their entire lives, that these are processes that their safety has been proven by their endurance over time. But you all don’t need to hear that. I am speaking to the converted here.”

Where Science Meets Industry

TFA aims to fill a niche in the world of fermentation. There are plenty of DIY fermentation festivals, food and beverage industry conferences and trade shows. But TFA connects science and industry.

Attendees at the event included an array of professionals involved in fermentation – producers, retailers, chefs, scientists, researchers, authors, suppliers, educators and regulators. The conference revolved around three tracks: food, flavor and culture; science and health; and business, legal and regulatory. The group of passionate fermenters in attendance uniformly expressed their excitement and delight to learn from experts in different disciplines.

“This unique conference had the most diverse attendees as it included chefs, scientists and more,” said Glory Bui, a graduate student researcher at the University of California, Davis. “It was nice to network with those who were and were not in academia to hear different perspectives in the fermentation industry.” [Bui won the student poster competition with her research on how fermented dairy products can affect gastrointestinal health.]

Producers made up over 40% of attendees and ran the gamut from small to large scale. Sash Sunday, founder and fermentationist behind OlyKraut in Olympia, Wash., said she’s been searching for such a fermentation conference since starting her brand in 2008.

“I really appreciate getting to spend time getting to know other fermenters, hearing about people’s creative processes and experiences in the field,” Sunday said. “I really loved all the tastings and spending time with people who really think about the flavors in fermented foods.”

Niccolo Fraschetti, owner of Alive Ferments, said networking was one of his favorite parts of the conference.

“There were people there that were superstars of fermentation to people making kimchi in the bathtub,” Fraschetti said. “It was such a cool merging of fermentation.”

Fraschetti officially launched Alive Ferments in March and said he never expected the brand to grow so fast, so quickly. Alive Ferments currently is sold in 25 stores in the San Diego area. At FERMENTATION 2022, he brainstormed ideas with attendees and speakers.

“Usually I feel like in these situations, everyone is tight-lipped and doesn’t want to share (business secrets),” he said. “But everyone was a really embracing community and willing to share their knowledge. There was no competition between the peers that were at the conference.”

Connecting with others in the industry was a highlight, too, for Suzette Smith, founder of Garden Goddess Ferments and Pick up the Beet in Arizona.

“I loved that like minds were able to come together sharing similar passions,” Smith said. (I also loved “learning what’s new in the promotion of fermented foods.”

Gregory Smith, an independent chef based in Pittsburgh, said he “drove back from Chicago with my mind racing about all the things I learned.” He said the various chefs who spoke at the conference – like Flynn, Brock, Ismail Samad of Wake Robin Foods, Jessica Alonzo of Native Ferments, Misti Norris of Petra and the Beast and Jeremy Kean of Brassica Kitchen – inspired him to dive into upcycling.

“I’m excited about the way they made me look at food waste in the kitchen space and how to help utilize waste and taking excess product and converting it into something tasty,” said Smith, who runs his independent culinary service Thyme, Love & Culture with friend Romeo Kihumbu.

Karen Wang Diggs, founder of the ChouAmi fermentation device, spoke at the event in a session on fermenting with medicinal plants. She said it was “an honor” to speak at FERMENTATION 2022.

“I got to hang out with a bunch of really cool, ‘cultured,’ fermenting people – and the presentations were fabulous,” she said.

Added Neal Vitale, executive director of The Fermentation Association: “It was a privilege to have a stellar lineup of speakers. It was great to get to get together at last and explore so many aspects of fermentation.”

Focus on Food

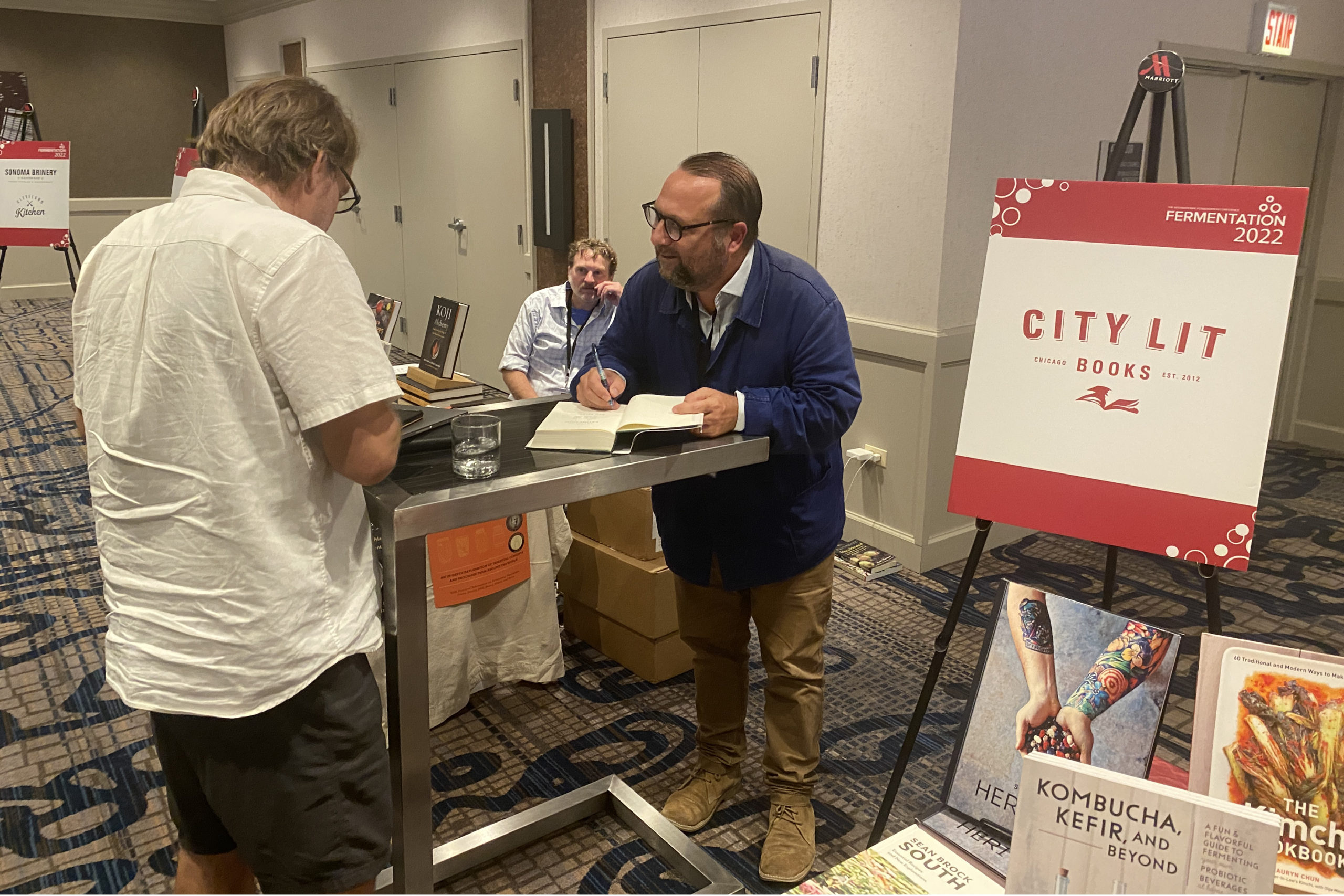

Other events at the conference included: a dinner with a fermentation-focused menu prepared by Rick Bayless, chef and restaurateur; a mezcal tasting with Lou Bank, founder of SACRED and the Agave Road Trip podcast; a craft beer and chocolate pairing with Long Beach Beer, Bread and Spirits Lab; a flavor analysis workshop with Sensory Spectrum Inc.; a screening of Ed Lee’s film Fermented (complete with buttered popcorn!); and multiple book signings.

Bayless, the James Beard Award winner who runs multiple Chicago restaurants, mingled with conference attendees during the dinner. He said he and his staff enjoyed the challenge of putting something fermented in every course.

“This is the first time we’ve done a meal that is so heavily fermented,” he said, “and we had a lot of fun doing it.”

Courses included a fermented corn masa tamal, beed with a fermented black bean sauce made with black bean miso and Oaxacan pasilla chile, smoked yellowfin tuna in a broth of tejuino (fermented corn drink), and chocolate from Tabasco, Mexico, with tepache (fermented pineapple) sorbet .

“I was at a conference with Sandor Katz years ago and I talked to him about making black bean miso, and now I get to serve it to him,” Bayless said.

The Fermentation Association was started in 2017 as the brainchild ofJohn Gray, then the owner of Bubbies Pickles. His goal was simple – to bring together everyone in the world of fermentation. Today, TFA circulates its biweekly newsletter to nearly 14,000, is followed by over 11,000 on Instagram and will next develop its presence on LinkedIn. The Association is run by a small staff and a 22-member Advisory Board, including six Science Advisors.

FERMENTATION 2022 was originally planned to be a May 2020 event, but obviously postponed due to Covid-19. A virtual FERMENTATION 2021 was held in November 2021. TFA will announce plans for 2023 and beyond in the coming months.

- Published in Business, Food & Flavor, Health, Science

Jason White Leaves Noma Amidst Its “Biggest Transformation”

Jason White has resigned as director of fermentation for Noma. He will be CEO and co-founder of a yet-to-be-announced biotechnology company in the United States. White tells The Fermentation Association that he will share details of his new project in the coming weeks.

Regarded as one of the best restaurants in the world, Noma earned their third Michelin star last year.

This summer, Noma owner Rene Redzepi announced that 2023 – the 20th anniversary of Noma – will be “our final year with Noma as we know it.”

“We have a plan, and I can’t wait to share more with you later this year, but for now, know that big changes are happening,” Redzepi wrote on Instagram, adding it’s “our biggest transformation so far…We’ve been laying some new foundational stones so we can continue to grow as an organization for the next 20 years.”

The staff had planned to take off this fall to travel to an undisclosed (but rumored to be in Mérida, Mexico) international location to learn some new cooking techniques and open a pop-up restaurant. But both the travel and pop-up have been postponed until spring 2023 due to ongoing travel restrictions related to the Covid-19 pandemic.

Last year Noma launched Noma Projects, a direct-to-consumer product line aimed at generating more revenue for the restaurant. In June, Bloomberg reported the restaurant was unprofitable in 2021 – the first time in four years – losing 1.69 million krone (~$225,000) after recording a small profit the prior year. Noma also received 10.9 million krone (~$1.45 million) from the Danish government in Covid-19 relief.

Noma’s previous head of the fermentation lab, David Zilber, also left the restaurant for a job in the biotech industry. He is a food scientist at Chr. Hansen.

White, who spoke at the 2nd international Food Innovation Conference this summer (produced by the Gottlieb Duttweiler Institute (GDI)), said fermentation is motivating scientists to listen to gastronomers.

“There’s going to be a huge exchange in this two-way road that we’re living in. Innovation in flavor coming from gastronomy and innovation coming from a high-level biotechnology, they are going to be harmonious,” White said. “We’re going to be able to create this infrastructure and community of people who have the same goal, and the same goal is going to be the wellness of our planet.”

- Published in Business

Chicago: A Fermentation Hub

If you still think of hot dogs and deep dish pizza as the icons of Chicago’s culinary scene, you need to think again. The so-called Capital of the Midwest is a hub of innovation in the food industry. Chicago has the largest food and beverage production in the U.S., with an annual output of $9.4 billion. Food startup companies in the region raised $723 million in venture capital last year.

“Chicago is one of the most diverse cities for eating,” says Anna Desai, Chicago-based influencer of Would You Like Something to Eat on Instagram. ”Our culinary scene is constantly elevating and evolving. We are always just a neighborhood or tollway away from experiencing a new culture and cuisine. I’m most excited when I find an under-the-radar spot or discover a maker who can pair flavors and ingredients that get you curious and wanting more.”

Desai started her blog in part because she wanted to champion the Asian American and Pacific Islanders (AAPI) community in the Chicago food and beverage scene. “Food has long served as a cultural crossroad,” she adds, and Chicago’s multicultural cuisine exemplifies that sentiment.

Chicago is home to some of the most creative minds in fermentation, from celebrity chefs, zero waste ventures, alternative protein corporations and the world’s largest commercial kefir producer. There are dozens of regional and artisanal producers lacto-fermenting vegetables, brewing kombucha and experimenting with microbes in food and drink.

“Chicago is a great food city in its own right, so naturally there is a ton of talent in the fermentation space,” says Sam Smithson, chef and culinary director of CultureBox, a Chicago-based fermentation subscription box. “The pandemic’s effect on restaurants has also spawned a new wave of fermenters (ourselves included) that are looking for a path outside the grueling and uncertain restaurant structure to display our creative efforts. This new wave is undoubtedly community-motivated and concerned more with mutual aid than competition. There is a general feeling that we are all working towards the same goal so cooperation and collaboration is soaring and we are seeing incredible food come from that.”

Flavor is King

Flavor development is still the prime motivation for chefs to experiment with fermentation. A good example is at Heritage Restaurant and Caviar Bar in Chicago’s Humboldt Park neighborhood.

“Fermentation has been a cornerstone of the restaurant since its inception,” says Tiffany Meikle, co-owner of Heritage with her husband, Guy. “With the diverse cuisines we pull from, both from Eastern and Central Europe and East Asia, we researched fermentation methodologies and histories, and started to ‘connect the dots’ of each culture’s fermentation and pickling backgrounds.”

Menus have included sourdough dark Russian rye bread, toasted caraway sauerkraut, kimchi made from apples, Korean pears and beets and a kimchi using pickled ramps (wild onions). Heritage has also expanded their fermentation program to the bar, where they’ve created homemade kombucha, roasted pineapple tepache, sweet pickled fruits for cocktail garnishes, and kimchi-infused bloody mary mix.

“It’s fascinating to me that there are so many ingredients you can use in a fermented product,” says Claire Ridge, co-founder of Luna Bay Booch, a Chicago-based alcoholic kombucha producer. “People are really experimenting with interesting ingredients in kombucha…I have seen brewers do some of the wildest recipes and some recipes that are very basic.”

Innovating Food

Chicago-based Lifeway Kefir is indicative of the innovation taking place in the city. Last year the company expanded into a new space: oat-based fermentation, launching a dairy-free, cultured oat milk with live and active probiotics.

“We’ve spent so many years laying the groundwork in fermented dairy,” says Julie Smolyansky, CEO. “Now we’re experimenting and expanding to see what’s over the next horizon, though we’ll always have kefir as our first love.”

Chicago is home for two inventive fermented alternative protein startups: Nature’s Fynd and Hyfé Foods. Both companies were born out of the desire to create alt foods without damaging the environmental.

“Conscious consumerism is a trend that’s driving many people to try alternative proteins, and it’s not hard to understand why,” says Debbie Yaver, chief scientific officer at Nature’s Fynd. The company uses fermentation technology to grow Fy, a nutritional fungi protein. “Fungi as a source of protein offer a shortcut through the food chain because they don’t require the acres of land or water needed to support plant growth or animal grazing, making fungi-based protein more efficient to produce than other options.”

Alternative foods outlasting the typical trend cycle is a challenge for companies like Nature’s Fynd. When grown at scale, Fy uses 99% less land, 99% less water and emits 94% fewer greenhouse gasses than raising beef. But, to make an impact, “we need more than just vegans and vegetarians to make changes in their diets,” Yaver adds.

Waste Not

Numerous companies are using fermentation as a means to eliminate waste. Hyfé Foods, another player in the alternative protein space, repurposes sugar water from food production to create a low-carb, protein-rich flour. Fermentation turns a waste product into mycelium flour, mycelium being the root network – or hyphae (hence the company name) — of mushrooms.

“[We’re] diverting input to the landfill and reducing greenhouse gas emissions at scale,” says Michelle Ruiz, founder. “Hyfé operates at the intersection of climate and health, enabling regional production of low cost, alternative protein that reduces carbon emissions and is decoupled from agriculture.”

Symmetry Wood is another Chicago upcycler. They convert SCOBY from kombucha into a material, Pyrus, that resembles exotic wood. Founder Gabe Tavas says Pyrus has been used to produce guitar picks, jewelry and veneers. Symmetry uses the discarded SCOBY from local kombucha brand Kombuchade.

Many area restaurants and culinary brands also use fermentation to preserve food for the long Chicago winters, when local produce isn’t available. Pop-up restaurant Andare, for example, incorporates fermentation into classic Italian dishes.

“Finding ways to utilize what would otherwise be waste products inspired our initial dive into fermentation. The goal is not just to use what’s leftover, but to make it into something delicious and unique,” says Mo Scariano, Andare’s CEO. “One of our first dishes employing koji fermentation was a summer squash stuffed cappellacci served with a butter sauce made from carrot juice fermented with arborio rice koji. Living in a place with a short grow season, preservation through fermentation allowed us access throughout the year to ingredients we only have fresh for a few weeks during the summer.”

Industry Challenges

Despite growing interest and increasing sales, fermenters face some significant hurdles.

Smithson at CultureBox says he sees that consumers are open to unorthodox, less traditional ferments. Though favorites like kombucha and sauerkraut dominate the market, “their share is being encroached on by increasingly more varied and niche ferments.” But getting these products to market can be a challenge. Small-scale, culinary producers are challenged by the regulatory hoops they need to jump through to legally sell ferments – especially unusual ones a food inspector doesn’t recognize.

“The added layer of city regulations on top of state requirements, sluggish health department responses, and inflexible policy chill the potential of small producers,” Smithson says. But he highlights the recently-passed Home-to-Market Act of Illinois as positive legislation helping startup fermenters.

Consumer awareness and education are also vital. “Many longstanding and harmful misconceptions on the safety and value of fermented products still exist,” Smithson says.

Matt Lancor, founder and CEO of Kombuchade makes consumer education a core part of marketing, to align kombucha as a recovery drink.

“Most mainstream kombuchas are marketed towards the yoga/crystal/candle crowd, and I saw a major opportunity to create and market a product for the mainstream athletic community,” he says. “We’re on a mission to educate athletes and the general public about these newly discovered organs [the gut] – our second brain – and fuel the next generation of American athletes with thirst quenching, probiotic rich beverages.”

Product packaging provides much of a consumer’s education. Jack Joseph, founder and CEO of Komunity Kombucha, says simplicity is key.

“People are more conscious of their health now, more than ever before,” he says. “So now it comes down to the education of the product and creating something that is transparent and easy for the consumer to digest.”

Sebastian Vargo of Chicago-based Vargo Brother Ferments agrees.

“Oftentimes food is considered ‘safe’ due to lack of microbes and how sterile it is,” he says. “Fermentation eschews the traditional sense of what makes food ‘safe’. We need to create a set standardized guide for fermented food to follow, and change our view of living foods in general. One of the brightest spots to me is the fact that fermentation is really hitting its stride and finding its place in the modern world, and I don’t see it going anywhere but up in the near future.”

- Published in Business, Food & Flavor

Brewing Boom in Chicago

Dubbed the craft beer capital of America, Chicago has a brewery scene that is innovative and diverse. Numerous breweries have opened over the last decade, with now about 160 breweries across the city and surrounding suburbs. Ferment Magazine says Chicago’s craft brew industry is “one of the most expressive and most exciting experiences anywhere in the world, let alone in the U.S.”

“We have a very strong culinary scene in Chicago and a lot of consumers that have an open mind. There’s a lot we could throw at the market and people are very accepting of the different brewing styles, both old world and new world,” says Tyler Davis, founder and director of fermentation at Duneyrr Artisan Fermenta Project. “Of all the [different beer styles] we could produce, there are brewers in Chicagoland that specialize in that.”

Chicago’s Brewers

Duneyrr (pictured) focuses on co-fermentation. Using craft beer as a base, Davis makes fermented drinks with ingredients from wine, cider and mead.

“It all came from me reaching the end of my creativity in a brewery. I got tired of creating the same format,” says Davis, who worked in Chicago as head brewer at Lagunitas and at Revolution Brewing. He began experimenting with co-fermentation and found “how you ferment wine is shockingly similar to beer. There are nuances of both, but I enjoy blurring the lines.”

The Nordic-inspired drinks he produces include his favorite, Freya Franc,(a sour hybrid with passion fruit and Sauvignon Blanc grape must. Duneyrr also has a Moderne Dune line, a sister brand that specializes in modern ingredients and techniques.

Davis studied at the Chicago-based Siebel Institute of Technology, the oldest brewing school in the U.S. and alma mater to many area brewers. One alum is Dave Bleitner, who founded Off Color Brewing with his Siebel classmate, John Laffler. The two focus on funky fermentation.

“Even with our first flagship gose, Troublesome, we have always been fermentation-focused. Even when we are dumping in a bunch of rooibos tea and pumpkin pie spices into a beer, we believe beer needs a proper fermentation to work,” Bleitner says. “Maximizing flavor from yeast is always going to result in a superior beer. But beyond our focus on fermentation, we are not afraid to dump a bunch of rooibos tea and pumpkin pie spices into a beer. So the dual concepts of focusing on the basics of fermentation while teetering on the border of innovative and insane is something no one else should or can replicate.”

When Off Color launched in 2013, Bleitner and Laffler didn’t want to go the mainstream craft beer route. “We had some crazy idea that craft beer consumers wanted variety from their beer,” Bleitner said. They didn’t follow the usual craft beer formula of launching with an IPA. They started with lesser-known styles like gose and kottbusser. He notes “we really hit our stride with Apex Predator Farmhouse Ale.”

At 15 years old, Half Acre Beer is one of Chicago’s pioneers of the craft beer scene. The brewery is the third-largest independent brewer in Illinois and now distributes their beer all over the country. They run a brewery and taproom in Chicago. Their best seller is Daisy Cutter pale ale, but they also sell seasonal and monthly varieties.

“These days we’re kind of the older, bigger brewery among the smaller, newer breweries. We focus on hop-forward and traditional beers,” said Gabriel Magliaro, president of Half Acre. He echoed the sentiment expressed by Duneyyr and Off Color – Chicago brewers are a supportive community. “Today I think we can call Chicago a beer town and, no matter how you choose to define that, we show up well.”

The Next Beer Buzz

Craft beer brewers see increasing competition from the better-for-you, healthier fermented drinks, like kombucha, seltzer and low- or non-alcoholic beverages.

Duneyrr is starting to specialize in lower-alcohol fermented brews. Off Color, too, has added a lower-alcohol beer, a 2.5% ABV Belgian-style they call Beer for Lightweights.

Lagers are making a comeback as well. “A lot of old world brewing styles, there’s become a renaissance,” Davis says. He sees “candy beers” – filled with artificial flavors – going away. Bleitner, too, is not a fan – he calls hard seltzers “fermented pixie sticks”. But he’s found that consumers like flavor in their brews. When sales of Off Color’s Troublesome gose began to decline, adding lime juice revived the drink. They called it Beer for Tacos and “it took off almost immediately.”

In an era fraught with pandemic shutdowns, retail inflation and supply chain issues, brewers foresee challenges ahead.

“Obviously the pandemic has been a factor, one that is still playing out,” Magliaro says. “The on-premise was rocked and I don’t think anyone knows how that will look in five years.”

Climate change is affecting grain crops, “things we knew to be stable are now being highly influenced by the weather patterns,” Davis says. The hot weather is changing the nutrient level of grains, leading to grains higher in protein. “It’s pretty scary,” he says.

But beer will always find a way to thrive.

“We make something embedded in human culture,” Magliaro says. “Beer is a gathering liquid that has place almost anywhere for almost any occasion with so much heritage to its being. The industry, consumer landscape and world can do what it needs, but beer will live on.”

- Published in Business, Food & Flavor

Washington Brewers Sue Oregon

Three Washington breweries are suing the state of Oregon, arguing a law puts out-of-state brewers at an unfair disadvantage.

Oregon allows in-state brewers to sell their beer to licensed retail businesses. Out-of-state breweries that want to do the same must obtain a federal wholesaler’s permit, then use a licensed Oregon distributor. It’s expensive, especially for small- and mid-sized breweries.

Fortside Brewing Co. co-founder Michael DiFabio (pictured on the left with co-founder Mark Doleski) went through the arduous process four years ago, and founded a separate Oregon company (Fortis) just to distribute beer in the state. The process of getting their Washington beer to Oregon customers costs their brewery thousands of dollars a year. Fortside is one of the breweries involved in the lawsuit.

A Seattle Times article points out there is precedent for the case. A 2005 U.S. Supreme Court ruling “established the principle that states could not favor their own alcohol beverage industries.”

The breweries involved – which also include Mirage and Garden Path Fermentation – want Oregon to treat out-of-state breweries the same as they do for in-state ones. Oregon brewers submit a statement each month detailing how much beer they sold. The state calculates the tax due and the breweries pay, with no additional permits or distributor fees.

“We’re just trying to level the playing field,” DiFabio says.

Read more (Seattle Times)

- Published in Business

‘Ferming’ the Future of Food

The New York Times latest food article deep-dives into the precision fermentation that produces alternative foods, biotechnology that could turn the agriculture industry “from farming to ‘ferming.’”

The American food system is unsustainable, according to the article, with factories and feedlots producing one-third of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions. But scientists have an answer for producing protein-rich, sustainable, cheap food: precision fermentation. Using this biotech method, components of animal products (such as beef or eggs) are isolated, and then their cells are multiplied in large vats. But scaling is proving problematic.

“Precision fermentation is the most important environmental technology humanity has ever developed,” says George Monbiot, an ecologist and journalist. “We would be idiots to turn our back on it.”

Startups are lacking infrastructure and even knowledgeable employees “in a food industry trained to support animal farming.” Dr. Liz Specht, vice president of science and technology at the Good Food Institute, says we’re living in a “critical moment for governments to invest,” similar to what’s been done in the renewable energy sector in recent years. Regulations and intellectual property are also concerns.

Read more (The New York Times)

Hard Seltzer from Whey?

A professor of food science at Cornell University has launched a unique food product: a hard seltzer made from yogurt byproduct.

The seltzer, Norwhey, started as part of an academic research project by food scientist Sam Alcaine, who works in the Fermentation Lab at Cornell’s College of Agriculture and Science. It all began in 2016 when the New York Department of Environmental Conservation asked Cornell to solve a problem. The state, the largest producer of yogurt in the country, was concerned with the large amount of waste (whey) being thrown away. For every one cup of yogurt made, three cups of byproduct are produced.

That amounts to a huge amount of waste, with up to a billion pounds of whey produced each year just in the state of New York, Alcaine told Good Beer Hunting. The article notes that Greek yogurt producer Chobani alone generates 50 truckloads of whey per day.

“There is a lot of lactose floating out there, and I wanted to find out how we could ferment that in new and novel ways,” Alcaine said.

Historically, whey has been considered worthless since it contains no protein. But It does still have the vitamins found in milk — calcium, potassium, zinc, magnesium and vitamin B5— which spurred Alcaine to research how why could be made into something of value.

“In the brewing world, we’ve always looked for developing better-for-you products,” said Alcaine, who co-founded Denver’s Doc Luces Brewery and worked in new product development at Miller Brewing Company. “It’s been kind of a hard space to play in, with alcohol. So this is an opportunity. We just have to make it taste good.”

“There are actually some old stories around that, in Iceland, they would take the whey from skyr [a cultured dairy product similar to curd cheese] and they would put it into these barrels,” Alcaine said in a Cornell press release on Norwhey. “It would age and it would become alcohol. But it hadn’t been done in my lifetime.”

Norwhey is made by adding the enzyme lactase to whey, which breaks lactose into glucose and galactose. These sugars are then fermented traditionally.

Alcaine partnered with Trystan Sandvoss, founder of First Light Creamery and then Marketing Director at Old Chatham Creamery, to create Norwhey. The pair entered a food and agriculture competition, Grow-NY, in 2020, and made it to the final round. That same year, they secured $50,000 in funding from the FuzeHub Commercialization Competition, and used the prize money to test batches and can and label products at New York-based Meier’s Creek Brewing.

Norwhey was first available at retail in April at New York-based Wegmans grocery stores. The hard seltzer is currently offered inthree flavors: Glacial Ginger, Solar Citrus and Mountain Berry, all with an ABV of 4%. There are plans to open a taproom and to experiment with new flavors this summer.

Cornell notes Norwhey is a “triple threat.” The alcoholic drink has a better nutritional profile than beer, it recycles waste material and “it could eventually act as a model for dairy farmers looking for additional revenue.”

For his part, Alcaine says he does not want to quit his day job and become a business owner. He wants to remain a professor and a researcher. But he’s hoping people will copy his idea, building “a whey-based economy in New York” and a more sustainable yogurt industry globally.

Naked Wine

Olfactory properties are central to the wine drinking experience. But a chemical reaction known as light strike can ruin the rich aroma. When wine is exposed to ultraviolet or high frequency visible light, its smell can resemble marmalade. Sauerkraut or even wet dog.

This is why wine is stored and aged in dark bottles – the color glass is crucial to producing a great wine.

“Every technician knows about it,” says Fulvio Mattivi, a food chemist at the Edmund Mach Foundation in Italy. “But then the final decision as to what goes on the market is up to the head of marketing.”

Mattivi and collaborators recently published a paper in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences detailing how bottle color affects light strike in wine on grocery store shelves.

Clear bottles made of a refractive material called flint glass are often used to sell white wine and rosé, to show off the fermented beverage’s color. The new research shows that just a week on supermarket shelves in clear bottles can produce smelly compounds. “With exposure, you can have a very bad wine,” Mattivi said. This chemical origin of light strike, including the speed and conditions, has been unknown until Mattivi’s study. In his team’s research, more than 1,000 wine bottles in different grocery store conditions were studied.

Despite consumer preferences for clear bottles, Mattivi gives a hard “no.” He compares it to the folk tale, “The Emperor’s New Clothes.” In the Hans Christian Andersen story, the emperor is conned by swindlers into believing the new clothes they bring him are beautiful – but, in reality, there are no clothes and the emperor is naked.

Mattivi said: “Wine in clear bottles is naked.”

Read more (New York Times)

Scamming Restaurants

A new scam is threatening restaurants’ reputations: leaving one-star reviews.

In recent days, small, large and even Michelin-starred restaurants across the U.S. have received a barrage of poor reviews on Google. These have no descriptions nor photos, simply the infamous one-star rankings. And, as restaurants try to recover from the coronavirus pandemic, owners report that, days later, they receive an email from someone claiming they posted the review and, if the restaurant wants it removed, they must pay up. If they don’t, the bad reviews will increase.

“You’re just kind of defenseless,” said Julianna Yang, the general manager of Sons & Daughters in San Francisco, who has taken on much of her restaurant’s response to the messages. “It seems like we’re just sitting ducks, and it’s out of luck that these reviews might stop.”

Law enforcement is encouraging restaurant owners to contact Google, and to report these cybercrimes to their local police department, the F.B.I. and the Federal Trade Commission. Removing the reviews – and tracking down the anonymous posters – is an almost hopeless task. Google has an automated system to monitor reviews for abuses. But it’s challenging for restaurants to reach someone at Google, with many reviews never being removed.

“We don’t have a lot of money to fund this kind of crazy thing from happening to us,” said an owner of Sochi Saigonese Kitchen in Chicago. Her one-star reviews were removed after customers came to her defense on social media.

“This is another nightmare for us to handle,” said William Talbot, manager at EL Ideas Restaurant in Chicago. “I’m losing my mind. I don’t know how to get us out of this.”

Read more (The New York Times)

- Published in Business