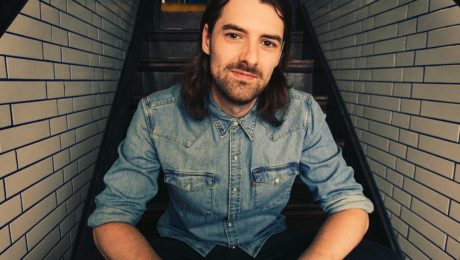

A Venn Diagram of Food, Biology & Chemistry: A Conversation with Johnny Drain

Johnny Drain is the guru for helping chefs around the world innovate flavorful dishes. A chemist with a PhD from Oxford and a passion for cooking, Drain found fermentation was the optimal intersection of food and science.

“Fermentation was this focus of this venn diagram that incorporated food with some necessity to understand biology but also chemistry,” Drain says. “Fermentation was this sweet spot where I could apply my background in science with this passion and knowledge and aptitude for cooking, flavor and taste. I realized if I wanted to apply this rich educational history that I was fortunate to have access to, fermentation was this ideal sphere where I could do that.”

This cross-section is where Drain finds his diverse career — as an in-demand food research and development consultant. He’s currently advising chefs in renowned restaurants all over the globe and serving as co-editor of MOLD magazine.

The Fermentation Association spoke with Drain, who is based in London. Below is the first of our two-part Q&A with Drain. Part 1 focuses on his interest in fermentation, and how he sees fermentation transforming the culinary world. Part 2 features some of Drain’s recent fermentation consulting projects and his drive to use fermentation to create a sustainable global food system.

The Fermentation Association (TFA): What got you first interested in fermentation.

Johnny Drain (JD): I am a scientist by background. I did chemistry as an undergraduate, then I worked for a company in finance, which I don’t really talk about. It was on the cusp of the financial crash, 2006-2008, so it was quite an interesting time to be working in that sector. During my lunch breaks, I was reading recipe books and reading restaurant reviews and looking at the world of science. I was thinking about doing a PhD, and I ended up quitting finance because I realized this was not how I wanted to spend my life, for 12 hours every day. I went back and did a PhD in something called material science, which is a cross between chemistry and physics. Still nothing actually to do with food, I was looking at how atoms interact in types of steel, and building computer models of how to understand that and how to apply that to making car chassis. So still, it was very far away from the world of making food, but always I had this dream of becoming a chef or maybe having a restaurant at one point in my life.

At the end of my PhD, I was fortunate to study in Oxford in this very beautiful place in the heart of England in this very rich academic history surrounded by all these very clever people and beautiful buildings. I realized, instead of becoming an Oxford don with maybe a tweed suit and patches on my elbows, I would sack that all in, having climbed up a few rungs of that ladder, and basically start staging (unpaid restaurant internship) and working in kitchens for free. I even worked as a pot washer in one kitchen in London. I really jumped back in at the deep end and pursued this dream of becoming a cook or a chef.

I did that for a little while and realized first, becoming a chef is a young person’s game. And second, I’m 6’2’’ and have a bad back and, as a chef, you’re standing on your feet all day and that was not going to be a physically viable way for me to make a living. I had to combine my scientific nouse (intellect) with my passion for food.

For me, the interesting thing is I never see these things as mutual exclusive, they’re all related and interconnected. I ended up doing what I do now, which is helping restaurants and bars and food brands, consulting and teaching restaurants and chefs how to understand these things. As I see it, I’m unlocking their artistry and storytelling ability through this understanding of science. All of these things are interconnected. And fermentation is this particularly excellent example. It has to do with flavor and food, but it also has to do with people and tradition and culture, it has to do with artistry and storytelling, you can’t really do one without the other. Science, that biology and chemistry, is really integral to unlocking the creative, artsy-fartsy elements to these types of food.

TFA: When you partner with these different chefs and kitchens, what expertise are they looking for from you?

JD: Especially these days, it’s different from five years ago when I first started doing this type of work. Five years ago when you’d go into a kitchen, people really wouldn’t know what fermentation was. And often they wouldn’t be interested in it, or they wouldn’t understand why might a scientist be able to help me make better, tastier food or drink. But now, most people I work with, they know that and they’ve already dibbled and dabbled a little bit with some of these ferments. Let’s say they’ve made some kimchi or sauerkraut or some kombucha. Really what they want now, especially the high end places, they’ve dibbled and dabbled and they want to make sure that, A, what they’re doing is safe and isn’t going to kill anyone, which is very sensible. But secondly, they want that kind of X factor, they want the ability to unlock that real deep magic. That’s when I go in.

I was just in Lithuania last week working with this really great restaurant called 1918. Michelin doesn’t cover Lithuania, give it two years I expect, and they’ll get at least 1 star, possibly 2. It’s really high end, great quality food. And they’re trying to play around with egg yolks and koji, which is basically this aspergillus, this war horse of Japanese food culture that’s also present in Chinese and Korean cultures as well. They want to be able to have that scientific rigor and have someone to come in “Pick that lock,” as I describe it, and be able to unleash their creativity so they can put this into action in their dishes. They’re wanting to tell these stories about Lithatian food culture and use this food they’re growing on this farm about 50 minutes outside the capital.

TFA: That sounds very rewarding, to help different restaurants create new dishes.

JD: It is. My role is this enabler, picking that lock, unleashing people’s creativity and helping these chefs. Really, fermentation is just a tool. In many ways, the way we see knife or a chopping board, it’s a tool. If you try and cook without those tools, you’re doing yourself a great disservice. You’re limiting what you can do, you’re limiting your creativity. Fermentation really is just another example of a type of tool. In five or 20 years, people will just see some of these fermentation techniques just as the way they see a knife. It’s just this tool. And by empowering these chefs with these tools, I’m helping to unleash that creativity. When you unleash people’s creativity they get very excited and very passionate.

TFA: Why do you think fermentation has become such a bigger interest among chefs?

JD: The funny thing about fermentation is we all eat fermented products, but we don’t realize it. You could read off a list that lasts five minutes. Bread, all booze, chocolate, coffee, vinegar, etc. It’s just that most of those products, we’ve become so used to them because there are these staples of everyday life that we don’t realize they’re fermented. Also partially because the way the food systems now work, that work of creating our own bread or beer or cider, it’s now been outsourced for most people in much of the world to some other party. So we’re not making these products at home where our grandmothers, our grandfathers, would have been. My grandmother would have understood that bread, wine, cider was a fermented product because she was making those or her grandmother was making those. Whereas I grew up in a household where we bought all of those things and somebody else made it. All those steps had already been performed.

First, there’s this awakening of realizing much of the food we know and love is fermented. And second, from a chef, foodie world, there’s been a renaissance in fermented food because they offer this exciting flavor profile that chefs always want. Chefs are looking for the new. Especially in the last 20 years, with that modernist cuisine movement, people reached science to kind of process foods. That’s where the novelness came. In the sort of last 10-15 years, we saw this move towards what new ingredients do we have on our doorsteps, foraging, this local-vore movement of people rediscovering what incredible food products are on their doorstep. Now people are asking “Where can we discover new flavors that are on our doorstep that are new, now that everyone has foraged everything. Where is the newness? Where can I reach out to access this incredible, novel flavor profile?” Fermentation is this toolkit that gives you access to these incredible new flavors. It’s the other frontier.

When you talk about what’s on our doorstep, we get into this idea of microbial territory.

What microbes are unique to Britain or unique to France or unique to Argentina? Actually, the microbes are as unique and defining of place and of the food culture in a place as the grapes that grow or the cheeses that we make or the strains of wheat varietals that might grow in a place. Microbes are sort of this hidden category of food that have shaped the food that we eat in the place that human beings live as much as any other kind of meat or dairy or fruit or vegetable.

TFA: What do you think is the future of fermentation in the culinary world?

JD: So the focus now is very much on people within the food industry looking for what produce they have in their backyard or in their country or their culture and how do they ferment those? I think, currently, the sort of toolkit of fermentation is dominated by a couple of prevailing techniques or cultures, microbiological cultures.

I think there is so much to learn from slightly undiscovered fermentation food cultures in the world. Ones that really haven’t had a bright light shone on them — like the Japanese, fermentation has had quite a bright light shone on them. And that’s amazing because Japanese fermentation culture is amazing and incredibly rich, so lots of people around the world have learned a lot from it. I think the next frontier for me is going to be people looking at fermentation in Sub-Saharan Africa, fermentation in the Indian sub continents. And those fermentation cultures are currently not that well understood, certainly by people outside those cultures, and they’re not documented in clear and concise ways in much of the way now that that Japanese food culture and Western European fermentation food culture has been documented. I think people are realizing there’s all these incredible, beautiful, rich ferments that we just don’t know about and don’t understand in Sub-Saharan African and the Indian subcontinents. I’m currently working on projects with people who are from those countries and cooking the food of those cultures. There’s just so much for us to learn.

TFA: What’s been the wackiest or funkiest food thing you’ve ever fermented?

JD: On the menu at one point at Cub (restaurant in London where Drain worked in research and development), we had a pest season where the head chef was trying to base the menu around things that are perceived as pests or invasive species.

In the UK we have this animal called the Reeves’s muntjac. It came originally from India. This guy called Reeves visited India as this colonizing force and came back and had, as a rich guy, a bunch of these species of flora and fauna as pets and novelties, one of which was this Reeves’s muntjac. It’s a very small, muscular deer. It’s bigger than a bulldog, but as muscular, then with a head of a deer and these horns. You see them driving along British country lanes at night and they look very scary, they basically look like devil dogs. They look like the harbingers of the apocalypse, sort of like something very bad is going to happen as you’re driving down the fog down this dark, British country lane. They’re very weird, scary and other worldly. They’re a pest and they outcompete the native species. So they are hunted to control their numbers.

So we made a muntjac garum. Using this technique of garum, which is a Roman word for fish sauce, we created this umami-rich, meaty garum. And that got used to dress these various, wonderful, meaty dishes. We did deer faggots. A faggot in the culinary sense of a word is the the offal of meat wrapped in the coals, part of the intestines, and basically pan fried. It’s a very traditional British dish. We made these deer faggots and dressed it in this muntjac garum.

That was quite a weird but delicious example of that whole 360 idea of sustainability in not just the techniques that we use but the produce we’re using. How do we use invasive species?

The conversation with Johnny Drain continues in our September 16 newsletter. To find out more information about Drain, visit his personal Instagram and the Instagram of MOLD magazine.

- Published in Food & Flavor

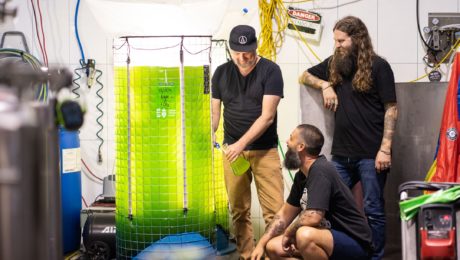

Recycling Brewery Carbon Dioxide Emissions

A brewery in Sydney, Australia is getting creative with the carbon dioxide emissions produced by yeast during fermentation. Young Henrys, with the help of a local university, is feeding those fermentation gases into tanks of native river algae that turn that CO2 back into oxygen. This process neutralizes the emissions. The CO2 produced to make one six pack of beer would take a tree two days to absorb.

“You have this really amazing yin and yang scenario,” said Oscar McMahon, Young Henrys co-founder. “One tank of algae is capable of creating the equivalent amount of oxygen as one hectare of Australian bush. It takes a long time to grow that, whereas we can grow a tank of algae within weeks.”

Read more (Bloomberg)

- Published in Business

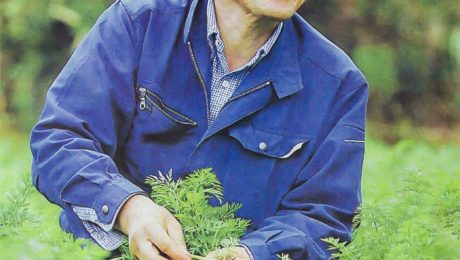

Farmer, Nutrition Activist Uses Fermentation Methods to Create Healthier School Lunches

An organic farmer and nutrition activist is teaching schools and daycare centers in Japan to grow their own vegetable garden using fermented compost from recycled food waste, then incorporate into school lunches those fresh vegetables with traditional Japanese fermented foods (like miso and pickles). Two years after the program’s launch, absences due to illness have dropped from an average of 5.4 days to 0.6 days per year.

Farmer Yoshida Toshimichi “is a devout believer in the power of microbes.” Using centuries of Japanese folks wisdom that is supported by modern science, Toshimichi explains that fermentation bacteria in the compost yields hardy, insect-resistance vegetables. He says the key to a healthy immune system is maintaining a diverse and balanced gut microbiota. “Lactobacilli and other friendly microbes found in naturally fermented foods can help maintain a healthy environment in the gut, just as they do in the soil,” continues the article. Microorganisms in fermented foods like miso and soy sauce will help balance gut flora. “Organic vegetables, meanwhile, provide the micronutrients and fiber on which those friendly bacteria thrive. In addition, phytochemicals found in vegetables—especially, fresh organic vegetables in season—are thought to guard against inflammation, which is associated with cancer and various chronic diseases,” the article reads.

Toshimichi has authored books on his farming and nutrition practices and is featured in the two-part documentary film “Itadakimasu,” which translates to “nourishment for the Japanese soul.”

Read more (Nippon)

- Published in Food & Flavor, Health, Science

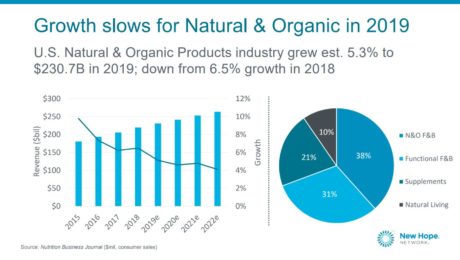

New Hope’s Report: 5 Trends for Fermentation Industry

Though the March Natural Products Expo West conference and trade show were cancelled this year because of the coronavirus pandemic, New Hope Network (producers of the event) hosted a virtual webinar this month to share their annual report on industry trends. Leaders from New Hope Network, SPINS and Whipstitch Capital shared insights on natural product sales trends.

“We definitely believe that this unfortunate health crisis is going to bring the bright spot of making health and wellness more mainstream,” says Kathryn Peters, executive vice president of business development at SPINS (who also are scheduled to present at TFA’s FERMENTATION 2021 conference next May).

The report typically encompasses sales numbers for the previous year, but SPINS included insights from short- and mid-term consumer behaviors during the COVID-19 crisis.

Read on for five takeaways for the fermentation industry from the data.

1. Thanks to Mass Market Saturation, Natural Sales Slow in 2019

Sales of the natural and organic industry in the United States slowed in 2019, growing 5.3% to $230.7 billion in sales.

The slowing growth signals an optimistic takeaway: mass market saturation. There are more natural products on retailer’s shelves than ever before.

“Despite the slower growth, the mass market channel – which includes big box retailers, large grocers like Walmart – that channel added 6.5 billion in new sales last year, which is very significant,” says Carlotta Mast, senior vice president for New Hope Network.

Sales data over the last decade shows the natural industry has grown from being a small player in the consumer products industry with only 11% of sales to a larger player with 20% of sales.

“We’re not a little kid anymore – we’ve kind of grown up,” says Nick McCoy, the managing director and co-founder of Whipstitch Capital.

Natural brands are getting larger, McCoy notes, experiencing an average of 10% growth two years after their start date. Growth of smaller brands is outpacing growth of larger brands. Brands in the 1,000-2,000 sales spots grew at a rate of 6.1% in 2019, while the top 1,000 selling brands grew at a rate of 5.2% in 2019.

2. Americans Want Functional, Science-Backed Products

Despite slower industry growth, the natural, functional food and beverage industry grew two times faster than conventional food and beverages in 2019. Functional products improve overall health by providing additional nutrients. Fermented food and drink fall into the functional category.

Functional food and beverage sales grew 5.3% in 2019, hitting $71.4 billion in sales.

Consumers are purchasing products with ancient wisdom, a trend defining the nutrient-dense, time-honored food that is made of simple, clean ingredients.

“This has been an underlying driver of the industry for many years,” Mast says. Consumers are “seeking science-backed health and wellness offerings positioned to address modern conditions.”

Consumers want optimized products that address eye health, stress support and, especially in today’s health climate, immunity.

The natural industry experts expect functional foods to continue to grow, fueled this year by the COVID-19 pandemic.

3. Coronavirus Outbreak Causing Big Boost in Sales

During the week America went into quarantine during the coronavirus outbreak, 15 million additional buyers bought natural products.

“At the end of the day, virtually everything sold,” Peters says. A key trend: “Natural products were still in demand; they did outsell all products.”

Peters notes some of the natural products may have sold because they were the last available product on the shelf. Time is the best indicator if these shoppers will convert to regulars. But those products are now on consumer’s shelves – and a lot product trial is happening across the country, trial that is an expensive element of product development. “It’s a huge opportunity for this industry,” Peters says.

“What we’re finding as a real highlight for the industry is the consumer values that built and grew the natural and organic industry for years and years are holding strong in the face of COVID-19,” Mast says. “One hypothesis of what the world may look like in a post-COVID era is that consumers will increasingly prioritize health and wellness…A number of long term macro forces and trends that have driven growth of the natural and organic products industry up until now position us well for a world in which consumers increasingly prioritize health and wellness.”

As unemployment soars and consumers cut back on expenses, Peters does not expect economic pressures will slow down natural product sales.

“Our bodies are our best line of defense, and consumers are realizing this,” she adds. “While comfort food is important in this phase, we are still seeing a strong influence of health and nutrient-dense food.”

A survey of consumers during the week of April 13, 2020 found that 77% say personal health is most important to them today than it was in 2019. In addition, 43% say eating healthy food is more important today than it was in 2019.

Sales of kombucha, for example, plateaued in 2019, after years of positive growth. But during the peak coronavirus grocery stock up period, refrigerated kombucha sales were up 28%, refrigerated pickle and marinated vegetables were up 58% and refrigerated yogurt sales were up 39%.

The coronavirus is increasing challenges for the industry, too. Supply chains are disrupted, there is a lack of new product development and a dearth of investment capital.

“That is slowing the flow of innovation, which we can expect to affect the flow of offerings to the market later this year and into 2021,” Mast says.

4. E-Commerce Sales Growing Fast, Driven by Natural Shoppers

In 2019, e-commerce sales accounted for only 4% of total natural product sales. In 2020 so far, e-commerce has generated almost $10 billion in sales. Estimates put total e-commerce sales at 17% in 2020.

“E-commerce is the big story for 2020 with COVID-19 and the rapid increase of consumers buying online,” Mast says.

Interestingly, natural shoppers were using e-commerce channels at a higher rate than regular shoppers.

5. Sustainability is of Greater Importance

Early consumer research indicates an aspirational trend: COVID-19 may change consumer’s viewpoints to become more sustainability focused.

During the week of April 13, 2020, a survey of consumers found that 67% said environmental health is more important to them today than it was in 2019. Purchasing behaviors that support environmental causes are also on the rise. Of more importance to consumers in 2020 verses 2019: food waste (36%), buying plant-based foods (29%), buying responsibly sourced meat, seafood and dairy (26%), buying organic (22%), and buying products with environmentally-based packaging (18%).

Sustainable packaging “which is really the Achilles heel to the natural and CPG industry,” Mast says, is becoming of greater important to consumers as single-use packaging is demonized. Brands are also looking for ways to keep their waste out of landfills, upcycle ingredients and putting byproducts back into circulation.

- Published in Business

Fermentation Grows Sustainable Alternative for Protein

The new wave of protein is not plant-based — it’s fermented.

“Fermentation is really cultivating microbes,” says Thomas Jonas, CEO and co-founder of Sustainable Bioproducts. “And it’s incredibly efficient. Microbes duplicate very fast. So when you think about the double time for a cow or a pig, you’re talking about years. When you talk about microbes, you’re talking about hours. … This is nature’s technology. Nature is really the No. 1 biotech engineer in the world.”

The current agriculture system is incredibly inefficient. Livestock continues to be the world’s largest user of land resources. Pasture land consumes 80% of total agricultural land. Fermented organisms are emerging as new sources of proteins and ingredients.

Leaders in the biotech industry shared how science is looking beyond plants to create food at a panel sponsored by The Good Food Institute.

Is Microbe Fermentation the New Era of Farming?

Sustainable Bioproducts creates a 50% protein based food ingredient from a microbe cultivated in the volcanic springs at Yellowstone National Park. Jonas explains that these fungal strains, called extremophiles, naturally produce a complete protein when grown in a controlled environment. Sustainable Bioproducts will soon move to a 36,000-square foot facility in Chicago’s former meatpacking district for production. The facility will take up just 0.7 acres. Compare the amount of food Sustainable Bioproducts produces to the equivalent of cow meat and 7,000 acres of grazing land would be needed for the cows.

“It’s the next generation of very efficient farming. I think what we want to get through farming are the nutrients that we need for our food. And microbes can do this tremendously efficiently,” Jonas said.

By fermenting proteins in bioreactors versus deriving the protein from plants or raising it and slaughtering it on a feedlot, food scientists can do a lot with the health profiles.

Michele Fite, chief commercial officer for Motif FoodWorks, said they work with microbes to adjust sensory attributes, like taste, smell, flavor and texture. “We can help so we don’t have to compromise taste or nutrition when consumers are looking to access plant based foods,” she said.

Adds Anja Schwenzfeier, business development manager for Novozymes: “You want to produce specific proteins that might already exist, but you want to do that more efficiently and more sustainably. You deal with molecules you’re already familiar with.”

“It’s not so much about creating a completely new protein. Right now we’re looking into how we can improve ingredients we already work with through fermentation.”

Fermentation as a Marketing Advantage

Panel moderator Jeff Bercovici, a writer for the Los Angeles Times, asked how biotech companies are meeting consumers in the development of fermented meat alternatives.

“(There is an) evolution of consumer attitude towards their food, which in some ways are really driving them very quickly to embrace meat alternatives, but in some ways there are some counter currents in terms of people wanting to eat whole foods, natural foods, foods with shorter ingredient lists,” Bercovici said.

The panel noted fermentation has long been a stable in the history of food, from beer to yogurt to cheese. As fermentation is making a comeback, it’s a “marketing advantage,” Bercovici notes, “now it’s a net positive, it generates consumer excitement.”

Fite at Motif FoodWorks said they’ve conducted research on meat alternative users. These consumers are currently buying meat alternatives because they believe it’s healthier than red meat and even chicken. “They want to be in this space,” she said. Consumers voice that meat alternatives are more sustainable, better for the environment, better for animal welfare and equally nutritious.

“They’re open to technology helping to solve that issue for them,” she said. “These consumers are more open to technical solutions than consumers that are a lot older have been in the past…there’s a gateway for these consumers to technical advancements, because they believe it aligns with their values.”

Adds Mark Matlock, senior vice president of food research at Archer Daniels Midland Company: “To me, it’s really refreshing to have some consumers who are embracing technology to this degree, to the extent that they may lead the mainstream their direction.”

Battling Land Use Challenges

As the global population grows, the great challenge to the environment over the next decade will be making more food with less space.

The average American consumes 215 pounds of meat a year. Raising that meat uses 32 million acres of land, and produces 82 million metric tons of greenhouse emissions.

“The real challenge for the planet is not going to be ‘Are we going to have enough oil or carbohydrates?’ it’s ‘Are we going to have enough protein?’” Matlock said. “We create protein the way a cow creates protein. … we have to think: where are our rare resources going to be put?”

A third of the corn crop grown in America feeds livestock.

- Published in Food & Flavor, Science

Sustainability Sells, Shoppers will Spend $150 Billion on Sustainable Goods by 2021

Sustainability sells. Shoppers will spend up to $150 billion on sustainable CPG goods by 2021, representing an increase of between $14 billion-$22 billion. – Nielsen Data

- Published in Business

Consumers: Brands We Buy Must Help the Environment

Sustainability isn’t just a buzzword, it’s a movement. Consumers care about the environment, and they want the brands they buy to care, too.

A recent Nielsen ratings report found that 81 percent of people around the world feel strongly that companies should help improve the environment. For proof consumers are pledging their support for companies that are Mother Nature’s advocates, look at their wallets. Nielson ratings found product sales grew twice as fast for companies with specific environmental impact claims.

“No matter what, sustainability is no longer a niche play: your bottom-line and brand growth depend on it,” the report reads.

Driving Growth

Nielson looked at three products sustainability efforts, two which are fermented: chocolate, coffee and bath products. Chocolate was the main focus of the report.

Cocoa is grown in difficult circumstances. Of the world’s cocoa supply, 90 percent of it is grown on small family farms by about 6 million farmers. Cocoa farmers work in rough circumstances. Cocoa is a fragile crop that grows in hot, rainy, tropical environments and the trees don’t yield cocoa pods until its fifth year. Farmers work hard and profit is low.

Research drilled down to specific consumer sentiments about chocolate, from environmental claims (like ethically sourced, made with renewable energy or carbon neutral), to the absence of artificial ingredients and fair trade.

Environmental Claims

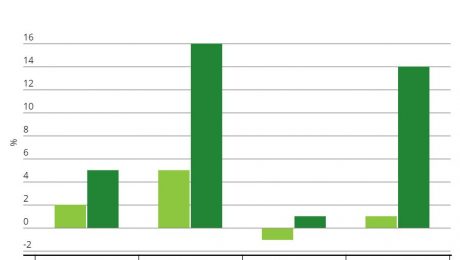

Chocolate with environmental claims account for an extremely small percent of the chocolate category, only 0.2 percent. But it grew four times the rate of sales, from 22 percent from March 2017 to March 2018. Unit growth is also huge. Chocolate with environmental claims is “flying off the shelves at a rate five times faster than the overall market.” Environmental chocolate had a 15 percent unit sales growth compared to the competition with just 3 percent sales growth.

Fair trade

Fair trade chocolate is performing well, too. Fair trade chocolate only makes up 0.1 percent of the total chocolate market, but dollar sales growth for fair trade chocolate doubles the rest of the category (10 percent versus 5 percent). Unit sales are five times higher for fair trade chocolate (15 percent versus 3 percent).

No artificial ingredients

Unit sales of chocolate made without artificial ingredients are growing at the same 3 percent rate as the rest of the chocolate category. But dollar sales of clean chocolate are triple the market (16 percent versus 5 percent). The report infers that, because clean chocolate is priced higher than chocolate made with artificial ingredients, consumers will pay more for a sustainable choice.

The report reads: “In many ways this space is evolving; however, what we do know is that sustainability presents an opportunity to be creative about innovative growth. Embedding consumer demand for sustainability into your company strategy and product pipeline requires data specific to your brand footprint and consumer profile.

Sustainability: “Life and Death Matter”

Consumers are empowered by evidence that “sustainability has become a life and death matter.” The World Health Organization estimates 12.6 million people die every year from environmental health risks. Air pollution and water quality are listed as top concerns for people around the world, the survey found. Increasing cases of asthma and typhoid are linked to deteriorating air and water quality.

“In light of these concerns, consumers around the world are making adjustments in their shopping habits,” the report reads. “While still juggling convenience, price and awareness along with their need to better the world, they’re looking for companies to step up as partners in their quest to do good.”

Another finding of note: though protecting Mother Earth is an important issue for survey respondents globally, consumers in developing countries are more concerned. The percentage of European and North American respondents who said they were “extremely” or “very concerned” about environmental issues was lower than respondents in third-world countries, like Latin America, Asia-Pacitic and Africa/Middle East.

Other interesting finds: environmentally advocacy is typically attributed to Millennials. Millennials are the generation most vocal advocating for corporate social responsibility. But the ratings found every generation and every gender cares deeply about the health of the planet. While 85 percent of Millenials (age 21-34) ranked a company’s environmental responsibility as “extremely” or “very” important, other generations weren’t far behind. Generation Z (15-20) was at 80 percent, Generation X (age 35-49) was at 79 percent, Baby Boomers (age 50-64) were at 72 percent and the Silent Generation (age 65+) was at 65 percent.

Environmental Champions

Forbes shares a detailed list of how companies can “champion” climate change. Their tips relevant to food producers include:

- Measure your carbon footprint annually through a third party audit.

- Develop an action plan, from reducing supply chain emissions to improving energy efficiency to cutting unnecessary transportation environmental hazards, like shipping by sea freight instead of air or using regional warehouses.

- Set emission reduction goals, then monitor your progress.

- Support environmental change politics by using lobbying influence for policymakers who are working to improve the health of the planet.

- Published in Science

What You Need to Know About the Changing “Use By” Dates

When in doubt, throw it out? Smell check? Taste test? Eyeball it? Food date labels have become so confusing that many consumers use their own sensory check to decode food expiration dates.

The food industry noticed. “Use By” dates are becoming uniform, with nine in 10 grocery store products now printing consumer-friendly labels. By 2020, all products will carry a simplified date. The 10 date-label categories will pair down to two – “Best if Used By” and “Use By.”

From Farm to Trash

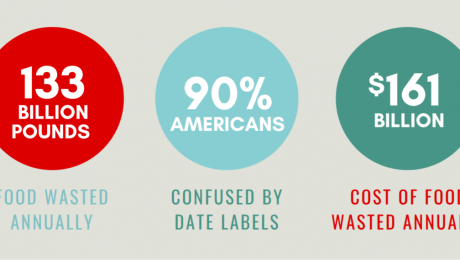

Critical to food product relabeling is curbing massive amounts of food waste. A study by Harvard Law School’s Food Law and Policy Clinic and the Natural Resources Defense Council found more than 90 percent of Americans are throwing away food before it goes bad because they misinterpret the food label.

“Expiration dates are in need of some serious myth-busting because they’re leading us to waste money and throw out perfectly good food, along with all of the resources that went into growing it,” said Dana Gunders, NRDC staff scientist. “Phrases like ‘sell by,’ ‘use by,’ and ‘best before’ are poorly regulated, misinterpreted and leading to a false confidence in food safety. It is time for a well-intended but wildly ineffective food date labeling system to get a makeover.”

Over 40 percent of the American food supply doesn’t even make it to a plate. That amounts to $165 billion worth of food that’s thrown away annually. Food waste has become the single largest contributor of solid waste in U.S. landfills. The USDA and EPA set the first national food waste reduction goal in 2015: 50 percent less food waste by 2030.

Industry Move

The product labeling initiative was launched in 2017 by the two largest grocery trade groups – the Grocery Manufacturers Association and the Food Marketing Institute. Geoff Freeman, GMA president and CEO, called it a “proactive solution to give American families the confidence and trust they deserve in the goods they buy.”

The standardized labels are not mandatory. They are voluntary.

The USDA Food Inspection and Safety Service made the recommendation in 2016 for food manufacturers to to apply “Best if Used By” to product label. But the industrywide label standardization is not government mandated.

“Virtually every discussion included concerns regarding waste generated as a result of consumer confusion about the various date labels on foods and what they mean,” said Mike Conaway, R-Texas, the House Agriculture Committee Chairman. “I am pleased to see the grocery manufacturing and retail industries tackling this issue head on. Not every issue warrants a legislative fix, and I think this industry-led, voluntary approach to standardizing date labels is a prime example.”

Dozens of consumer packaged goods brands and retail companies voted unanimously to change expiration dates exclusively to “Use By” by January 2020. Major brands like Walmart, Campbell, Kellogg and Nestle all spearheaded the change.

The 2020 date was set to give companies time to change dates on their packaging. It also coincides with the release of the new FDA nutrition facts panel.

Simplified Labels

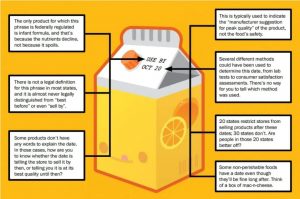

The old labels – which included options like “Sell By” and “Display Until” – left consumers in a guessing game. Most products don’t include an explanation of the date, like whether it’s a descriptive feature for the store or the consumer. Even grocery store workers were confused. Employees were polled and reported they, too, cannot distinguish dates on food labels.

The new labels mean:

- “Best If Used By” – quality designation. This is the date the food manufacturer thinks the product should be consumed for peak flavor.

- “Use By” – safety designation. Perishable food is no longer food after this date.

Legal Change on Horizon

Is a government mandate likely?

Currently, the only product federally regulated for expiration dates is infant formula. There is no legal definition for food expiration dates in most states. And state food labeling standards vary widely – 20 states restrict stores from selling products after the expiration date, while 30 states don’t enforce such a rule.

The Food Date Labeling Act was introduced to Congress in 2016, but no further action has happened. The act would legally require food date standardization, and require the USDA and Department of Health and Human Services to educate consumers on date label meanings.

Interesting, the proposal also questions the subjective nature of expiration dates. It states no one could “prohibit the sale, donation or use of a product after the quality date for the product has passed.”

- Published in Business

Student Creates Scoby Food Packaging; Fermentation Growth Just Two Weeks

Today’s food is packaged in so much plastic that humans now regularly consume plastic molecules in their food. A Polish design student created Scoby packaging, an edible and recyclable packaging that farmers can grow to wrap products. The zero waste biological tissue is a similar texture to animal tissue used to encapsulate sausage or salami, but Scoby is vegetarian and can be grown with a simple chemical process student Roza Janusz of the School of Form in Poznan, Poland invented. The process is similar to making kombucha, and the fermentation growth time per sheet is two weeks.

Read more (Fast Company)

- Published in Science

More Businesses in Chocolate Industry Implementing Sustainability Practices

The notoriously unsustainable chocolate industry is reevaluating business practices, according to a new study. As global demand increases, more companies are looking at sustainable cocoa sources. Jack fruit seeds are one growing alternative – once fermented and roasted, the flavor is similar to chocolate. Many confectionery companies are setting socially responsible policies and pledges, like Mars who is aiming for 100 percent sustainability by 2020.

Read more (Gourmet News)

- Published in Business