Managing Fermented Food Microbes to Control Quality

Fermented foods are produced through controlled microbial growth — but how do industry professionals manage those complex microorganisms? Three panelists, each with experience in a different field and at a different scale — restaurant chef, artisanal cheesemaker and commercial food producer — shared their insights during a TFA webinar, Managing Fermented Food Microbes to Control Quality.

“Producers of fermented foods rely on microbial communities or what we often call microbiomes, these collections of bacteria yeasts and sometimes even molds to make these delicious products that we all enjoy,” says Ben Wolfe, PhD, associate professor at Tufts University, who moderator the webinar along with Maria Marco, PhD, professor at University of California, Davis (both are TFA Advisory Board members).

Wolfe continued: “Fermenters use these microbial communities every day right, they’re working with them in crocks of kimchi and sauerkraut, they’re working with them in a vat of milk as it’s gone from milk to cheese, but yet most of these microbial communities are invisible. We’re relying on these communities that we rarely can actually see or know in great detail, and so it’s this really interesting challenge of how do you manage these invisible microbial communities to consistently make delicious fermented foods.”

Three panelists joined Wolfe and Marco: Cortney Burns (chef, author and current consultant at Blue Hill at Stone Barns in New York, a farmstead restaurant), Mateo Kehler (founder and cheesemaker at Jasper Hill in Vermont, a dairy farm and creamery) and Olivia Slaugh (quality assurance manager at wildbrine | wildcreamery in California, producers of fermented vegetables and plant-based dairy).

Fermentation mishaps are not the same for producers because “each kitchen is different, each processing facility, each packaging facility, you really have to tune in to what is happening and understand the nuance within a site,” Marco notes. “Informed trial and error” is important.

The three agreed that part of the joy of working in the culinary world is creating, and mistakes are part of that process.

“We have learned a lot over the years and never by doing anything right, we’ve learned everything we know by making mistakes,” says Kehler.

One season at Jasper Hill, aspergillus molds colonized on the rinds of hard cheeses, spoiling them. The cheesemakers discovered that there had been a problem early on as the rind developed. They corrected this issue by washing the cheese more aggressively and putting it immediately into the cellar.

“For the record, I’ve had so many things go wrong,” Burns says. A koji that failed because a heating sensor moved, ferments that turned soft because the air conditioning shut off or a water kefir that became too thick when the ferment time was off. “[Microbes are] alive, so it’s a constant conversation, it’s a relationship really that we’re having with each and every one on a different level, and some of these relationships fall to the wayside or we forget about them or they don’t get the attention they need.”

Burns continues: “All these little safeguards need to be put in place in order for us to have continual success with what we’re doing, but we always learn from it. We move the sensor, we drop the temperature, we leave things for a little bit longer. That’s how we end up manipulating them, it’s just creating an environment that we know they’re going to thrive in.”

Slaugh distinguishes between what she calls “intended microbiology” — the microbes that will benefit the food you’re creating — and “unintended microbiology” — packaging defects, spoilage organisms or a contamination event.

Slaugh says one of the benefits of working with ferments at a large scale at wildbrine is the cost of routine microbiological analysis is lower. But a mistake is stressful. She recounted a time when thousands of pounds of food needed to be thrown out because of a contaminant in packaging from an ice supplier.

“Despite the fact that the manufacturer was sending us a food-grade or in some cases a medical-grade ingredient, the container does not have the same level of sanitation, so you can’t really take these things for granted,” Slaugh says.

Her recommendations include supplier oversight, a quality assurance person that can track defects and sample the product throughout fermentation and a detailed process flow diagram. That document, Slaugh advises, should go far beyond what producers use to comply with government food regulations. It should include minutiae like what scissors are used to cut open ingredient bags and the process for employees to change their gloves.

“I think this is just an incredible time to be in fermented foods,” Kehler adds. “There’s this moment now where you have the arrival of technology. The way I described being a cheesemaker when I started making cheese almost 20 years ago was it was like being a god, except you’re blind and dumb. You’re unleashing these universes of life and then wiping them out and you couldn’t see them, you could see the impacts of your actions, but you may or may not have control. What’s happened since we started making cheese is now the technology has enabled us to actually see what’s happening. I think it’s this groundbreaking moment, we have the acceleration of knowledge. We’re living in this moment where we can start to understand the things that previously could only be intuited.”

- Published in Food & Flavor, Science

Noma Goes DTC

Noma is coming into the home kitchen.

The fermentation-focused restaurant, lauded as one of the top restaurants in the world, is selling its first line of packaged products. Two garums — vegan Smoked Mushroom and vegetarian Sweet Rice and Egg — will soon be available to ship internationally through the brand’s website, Noma Projects.

“It’s a space for us to channel our knowledge, our craft and experimentation into a new endeavor,” says René Redzepi, chef and co-owner of the Copenhagen-based restaurant.

Redzepi shared details of the launch in a video on the site. Noma Projects will include pantry products and community-based initiatives, “a way for us to address issues we care about through the lens of food.”

Noma’s Pantry Staples

The garums are Noma’s “take on a 1,000-year-old recipe that we’ve been developing over the past two decades.” Redzepi says the “potent, umami-based sauces” have been the “key to our success at Noma in our vegetarian and vegan menus.

He hopes the garums will help more people cook plant-based meals, announcing in the video: “We want to help you bring more vegetables into your everyday cooking.” The garums provide the flavor of meat and fish without the animal. The website description notes: “Shifting towards a more plant-based diet is the easiest way for an individual to help the environment. We hope these garums will do the same for you that they’ve done for us, help inspire and create more delicious plant-based meals when you cook at home.”

These products were developed in Noma’s Fermentation Lab, where dozens of pantry staples were tested before landing on the garums. A garum is the “concentrated essence of its main ingredient” with a strong umami flavor, and Redzepi describes it to the WSJ. Magazine (the luxury magazine published by Wall Street Journal): “It has the potency of a soy sauce, except it tastes of what it is.” Both are brewed with koji rice, what Redzepi calls the “mother fungus.”

The garums are currently fermenting and will be ready for shipping in the fall or winter. The expected price point is $20-$35 for a bottle.

And more garums are in the works. Noma Fermentation Lab director, Jason Ignacio White, says a roasted chicken wing garum is next.

“It tastes like super chicken stock with umami,” White tells WSJ. Magazine, ”so it’s a familiar flavor, but there’s something about it that you can’t really put your finger on, that makes your tongue dance.”

Improving Profitability

Despite Noma’s expensive tabs — the 20-course tasting menu costs 2,800 Danish kroner (or around $447), and the wine pairing is another 1,800 Danish kroner (or around $287) — in the 18 years since it opened, the restaurant has hovered at only a 3% profit margin. Redzepi hopes Noma Projects will make more money. While it is “a family-run garage project,” its goal is to reach a million customers.

Like many restaurants around the world, Noma shut down during the pandemic. They reopened as a burger and wine bar in June 2020, and the walk-up, outdoor dining experience was such a success that it became a permanent restaurant, POPL.

Noma resumed regular operations on June 1, 2021. The pandemic closure allowed Redzepi and his team to finally tackle the retail brand, something he said they had debated for years.

- Published in Business, Food & Flavor

A New Breed of Animal-Free Milk

Can you imagine dairy-free milk without a nut or oat? An Israeli start-up is using precision fermentation to create animal-free milk “indistinguishable from the real thing.”

Imagindairy’s technology recreates the whey and casein proteins found in a mammal’s milk. The fermentation time is quick at 3-5 days, and the final product mimics the taste and texture of traditional dairy milk, without cholesterol or GMOs. The product is expected to be in stores in the next two years.

“Many food products are produced in fermentation, including enzymes, probiotics and proteins,” says Eyal Afergan, co-founder and CEO of Imagindairy. He emphasized how safe the product is. “In fact, on the contrary, fermentation process produces a cleaner product which is antibiotic free and reduces the exposure to a potential milk borne pathogens.”

Read more (Food Navigator)

Fermentation for Alternative Proteins

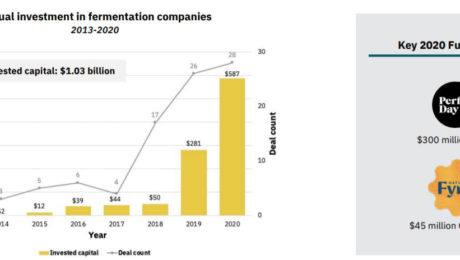

Investments in alternative protein hit their highest level in 2020: $3.1 billion, double the amount invested from 2010-2019. Over $1 billion of that was in fermentation-powered protein alternatives.

It’s a time of huge growth for the industry — the alternative protein market is projected to reach $290 billion by 2035 — but it represents only a tiny segment of the larger meat and dairy industries.

Approximately 350 million metric tons of meat are produced globally every year. For reference, that’s about 1 million Volkswagen Beetles of meat a day. Meat consumption is expected to increase to 500 million metric tons by 2050 — but alternative proteins are expected to account for just 1 million.

“The world has a very large demand for meat and that meat demand is expected to go up,” says Zak Weston, foodservice and supply chain manager for the Good Food Institute (GFI). Weston shared details on fermented alternative proteins during the GFI presentation The State of the Industry: Fermentation for Alternative Proteins. “We think the solution lies in creating alternatives that are competitive with animal-based meat and dairy.”

Why is Alternative Protein Growing?

Animal meat is environmentally inefficient. It requires significant resources, from the amount of agricultural land needed to raise animals, to the fertilizers, pesticides and hormones used for feed, to the carbon emissions from the animals.

Globally, 83% of agricultural land is used to produce animal-based meat, dairy or eggs. Two-thirds of the global supply of protein comes from traditional animal protein.

The caloric conversion ratios — the calories it takes to grow an animal versus the calories that the animal provides when consumed — is extremely unbalanced. It takes 8 calories in to get 1 calorie out of a chicken, 11 calories to get 1 calorie out of a pig and 34 calories to get 1 calorie out of a cow. Alternative protein sources, on the other hand, have an average of a 1:1 calorie conversion. It takes years to grow animals but only hours to grow microbes.

“This is the underlying weakness in the animal protein system that leads to a lot of the negative externalities that we focus on and really need to be solved as part of our protein system,” Weston says. “We have to ameliorate these effects, we have to find ways to mitigate these risks and avoid some of these negative externalities associated with the way in which we currently produce industrialized animal proteins.”

What are Fermented Alternative Proteins?

Alternative proteins are either plant-based and fermented using microbes or cultivated directly from animal cells. Fermented proteins are made using one of three production types: traditional fermentation, biomass fermentation or precision fermentation.

“Fermentation is something familiar to most of us, it’s been used for thousands and thousands of years across a wide variety of cultures for a wide variety of foods,” Weston says, citing foods like cheese, bread, beer, wine and kimchi. “That indeed is one of the benefits for this technology, it’s relatively familiar and well known to a lot of different consumers globally.”

- Traditional fermentation refers to the ancient practice of using microbes in food. To make protein alternatives, this process uses “live microorganisms to modulate and process plant-derived ingredients.” Examples are fermenting soybeans for tempeh or Miyoko’s Creamery using lactic acid bacteria to make cheese.

- Biomass fermentation involves growing naturally occurring, protein-dense, fast-growing organisms. Microorganisms like algae or fungi are often used. For example, Nature’s Fynd and Quorn …mycelium-based steak.

- Precision fermentation uses microbial hosts as “cell factories” to produce specific ingredients. It is a type of biology that allows DNA sequences from a mammal to create alternative proteins. Examples are the heme protein in an Impossible Foods’ burger or the whey protein in Perfect Day’s vegan dairy products.

Despite fermentation’s roots in ancient food processing traditions, using it to create alternative proteins is a relatively new activity. About 80% of the new companies in the fermented alternative protein space have formed since 2015. New startups have focused on precision fermentation (45%) and biomass fermentation (41%). Traditional fermentation accounts for a smaller piece of the category (14%). There were more than 260 investors in the category in 2020 alone.

“It’s really coming onto the radar for a lot of folks in the food and beverage industry and within the alternative protein industry in a very big way, particularly over the past couple of years,” Weston says. “This is an area that the industry is paying attention too. They’re starting to modify working some of its products that have traditionally maybe been focused on dairy animal-based dairy substrates to work with plant protein substrates.”

Can Alternative Protein Help the Food System?

Fermentation has been so appealing, he adds, because “it’s a mature technology that’s been proven at different scales. It’s maybe different microbes or different processes, but there’s a proof of concept that gives us a reason to think that that there’s a lot of hope for this to be a viable technology that makes economic sense.”

GFI predicts more companies will experiment with a hybrid approach to fermented alternative proteins, using different production methods.

Though plant-based is still the more popular alternative protein source, plant-based meat has some barriers that fermentation resolves. Plant-based meat products can be dry, lacking the juiciness of meat; the flavor can be bean-like and leave an unpleasant aftertaste; and the texture can be off, either too compact or too mushy.

Fermented alternative proteins, though, have been more successful at mimicking a meat-like texture and imparting a robust flavor profile. Weston says taste, price, accessibility and convenience all drive consumer behavior — and fermented alternative proteins deliver in these regards.

And, compared to animal meat, alternative proteins are customizable and easily controlled from start to finish. Though the category is still in its early days, Weston sees improvements coming quickly in nutritional profiles, sensory attributes, shelf life, food safety and price points coming quickly.

“What excites us about the category is that we’ve seen a very strong consumer response, in spite of the fact that this is a very novel category for a lot of consumers,” Weston says. “We are fundamentally reassembling meat and dairy products from the ground up.”

- Published in Business, Food & Flavor, Health, Science

Advances in Yeast

We’re in the midst of a yeast revolution, as genome sequencing creates opportunity for cutting-edge advances in fermented foods and drinks. Yeast will be at the forefront of innovation in fermentation, for new flavors, better quality and more sustainability.

“Understanding and respecting tradition is a key part of this. These practices have been tested for hundreds and thousands of years and they cannot be dismissed. There’s a lot the science can learn from tradition,” says Richard Preiss of Escarpment Laboratories. Priess was joined by Ben Wolfe, PhD, associate professor at Tufts University (and TFA Advisory Board member), during a TFA webinar, Advances in Yeast.

Preiss continues: “There’s still a place for innovation, despite such a long history of tradition with fermentation. A lot of the key advances in science are literally a result of people trying to make fermentation better.”

Wolfe, who uses fermented foods and other microbial communities to study microbiomes in his lab at Tufts, said “there’s this tradition versus technology conflict that can emerge.”

“I tell my students when I teach microbiology that much of the history of microbiology is food microbiology, it is actually food microbes, and they really drove the innovation of the field so it really all comes back to food and fermentation,” Wolfe says.

The technology relating to the yeasts used in fermentation has expanded enormously over the last decade, due heavily to advances in genome sequencing. Studying genetics allows labs like the ones Priess and Wolfe run to find the genetic blueprint of an organism and apply it to yeast. Drilling down further, they can tie genotype to phenotype to determine characteristics of a yeast strain. This rapidly expanding technology will disrupt and advance fermentation.

Priess predicted three areas of development for yeast fermentation in the coming years:

- Novelty Strains

Consumers have accelerated their acceptance of e-commerce during the Covid-19 pandemic and they’ll do the same for biotechnology, Priess says.

“Our industry does thrive on novelty,” he adds, noting there are beer brands already creating drinks with GMO yeast. “Craft beer is going to be the first food space where the use of GMOs is widespread — we’re seeing that play out a lot faster than I ever thought it would be with some of these products already on the market. Novelty does have value.”

Wolfe noted many consumers shudder at the idea of a GMO food or beverage, but microbes in beer are dead. Consumers are not drinking a living GMO in beer.

Yeasts also already pick up new genetic material naturally, through a process called gene transfer.

“It’s part of the evolutionary process that all microbes go through,” Wolfe says. “From my own lab and from other labs, cheese and sauerkraut and all these other fermented foods are showing so much genetic exchange that’s already happening.”

- Climate Change

The food industry must address growing concerns about climate change. Priess predicts breeding plants — like barley, hops and grapes — that are more drought-tolerant, or even using yeast technologies to increase yields or the rate of fermentation.

“Craft beer is massively wasteful,” Priess says. It takes between three to seven barrels of water to make one barrel of beer. “It is something we’re going to have to reckon with the next 10 years.”

Yogurt and cheese, too, produce large amounts of waste products.

- Ease of Genomics

The cost and time of genome sequencing has reduced significantly. It used to cost thousands of dollars and take many weeks to document a yeast genome. Now, it can be done for $200 in only a few days.

“The tools to deal with the data and get some meaning from it have never been more accessible. It’s incredibly powerful,” Priess says. “We’re developing solutions for products without millions of dollars.”

Priess does not agree with companies patenting yeasts, “it’s murky territory.” He believes fermentation and science should be about collaboration, not ownership and protection.

“Working with brewers and other fermentation enthusiasts, it’s this incredibly open and collaborative space compared to a lot of the industries,” he says. “I think that’s like our secret weapon or our secret value is that fermentation is so open in terms of access to knowledge as well as in terms of people being willing to experiment and try new things. That’s how it’s able to develop so quickly.”

- Published in Food & Flavor, Science

State of the Natural & Organic Industry

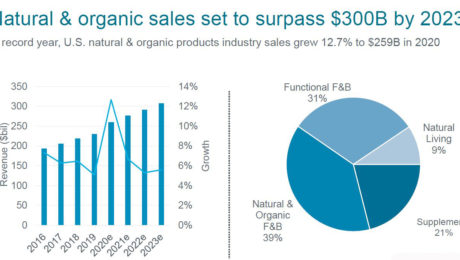

The Covid-19 pandemic powered strong food and beverage sales last year. But natural and organic brands grew even faster than conventional ones, with sales growing 12.7% to $259 billion.

“Natural products throughout the last year have really been outpacing all product growth. Natural and clean products are now about $1 out of every $10 spent, which is really significant,” says Kathryn Peters, executive vice president of SPINS, a retail data provider. Peters presented sales trends at the virtual Natural Products Expo West.

Data from SPINS and Nutrition Business Journal documents that there was a “dramatic shift” in consumer behavior during the pandemic, as more people cooked at home and bought healthier foods.

“2020 was a record year for the U.S. natural and organic product industry,” says Carlotta Mast, senior vice president and market leader for New Hope Network, producers of the Natural Products Expos. “The industry has so much to celebrate, despite the very challenging time we’ve been through the past 14 months.”

Natural and organic sales are expected to pass the $300 billion mark by 2023.

Food as Medicine

Functional food and beverage sales grew 9.4% to $78 billion in 2020, a surprisingly high figure since grab-n-go offerings — the category in which many functional products are tracked — were reduced significantly during the pandemic.

“And yet that strong growth, nearly 10% experienced in that category, demonstrates that people continue to embrace the food as medicine trend,” Mast says.

Products that claim to offer immune-boosting, functional ingredients are selling well. Consumers are “shifting from reactive to preventative and from cold and flu season to year-round protection.” Ingredients and supplements like elderberry, vitamins C and D, antioxidants, collagen and cider vinegar are increasing in sales.

Sales of animal welfare-positioned products grew 17% in 2020, and sales of grass-fed and free-range products increased more than 13%. Other key wellness attributes that appeared to drive significant dollar growth included paleo (up 32%), plant-based (21%) and grain-free (18%).

“Consumers are expecting more from the products they buy,” Peters said. “Whether it’s because of a limited budget or health and wellness considerations to build a stronger body, people are seeking nutritional benefits.”

Mission-Driven

Consumers are seeking to buy from brands with a purpose. These are products that, for example, want to save the environment, create a sustainable food system, champion a social justice cause or support a minority group.

Nick McCoy, co-founder and managing director at Whipstitch Capital, a food-focused investment bank, calls these brands “better for people and the planet” and says they are “doing good while making money at the same time.” The amount of ESG (Environmental Social Governance) investment funds has increased tenfold over the past two years.

Brands that are mission- and community-minded are experiencing the strongest sales growth.

“This demonstrates that our industry is home to brands that do a lot more than just sell a product — they’re a force for better, better health and better outcomes for humans, animals and the environment,” Mast says. “Our industry shoppers expect more than a transaction from the brands they do business with.”

In a SPINS survey, consumers said they want to support brands that are LGBTQ owned (19%), BIPOC owned (28%) and/or woman owned (18%).

Vegetarian and vegan products are also increasing in sales. Plant-based and meat alternatives grew 21% last year, at a rate of two-times their mainstream counterparts.

“In many cases, plant-based is bringing more nutrient density than the original animal-based analog,” Peters says . “Plant-based support is growing beyond just health benefits to earth-based benefits like lower greenhouse gas emissions, water conservation and biodiversity.”

E-Commerce

Not surprisingly, e-commerce sales fast-tracked during the pandemic, accounting for 58% of natural and organic sales last year. E-commerce also became the main channel where new brands were launched. Though sales in brick-and-mortar stores are not predicted to return to pre-pandemic levels, physical retail locations are still expected to account for 30% of all natural and organic products sales in 2023.

Speakers at the event advised brands to take an omnichannel approach, tackling marketing through brick-and-mortar stores as well as e-commerce channels. Sashee Chandran, founder and CEO of Tea Drops (a producer of organic tea pressed and preserved in different shapes), spoke at the conference about her experience following this marketing approach.

“Even though things are opening up, consumers still want that flexibility to be able to shop online but also in store,” she says.

- Published in Business

Dairy-Free “Vegurt”

Chr. Hansen, a global bioscience supplier of ingredients, has developed Vega Culture Kits, a new line of probiotic starter cultures that can be used to create plant-based yogurt. “Vegurt,” a shortening of vegan or vegetarian yogurt, is the name being used for this non-dairy product. This term was created in reaction to the European Parliament’s current debate over whether plant-based products can use dairy-related terms like yogurt and milk.

“Vegurt seemed a catchy and suitable category name compared to having to sprain our tongues calling them ‘fermented plant-based alternatives to dairy yogurt,’” said Dr. Ross Critenden, senior director for commercial development at Chr. Hansen.

The Vega Culture Kits are designed to “robustly ferment” any dairy-free plant base, like nuts, cereals, legumes or seeds. The Vega Culture will appear as “culture” on ingredient lists, in the same way that dairy yogurts include “culture” when cultures or probiotic strains are added.

Read more (Food Navigator)

- Published in Science

Building a Fermented Brand

Behind every fermented food or beverage is intriguing science that creates a pleasantly tangy taste. Customers want to know all about that chemical process, right?

No. Stop geeking out and appeal to the foodie instead.

“This is about the joy of eating, and so when you over-science me and you over-gut me, I forget the joy of eating. Remind yourself that your most important message is how pleasant, how tasty, how engaging, that’s the pleasure of eating, and then you can tell me how you make that pleasure,” says Sasha Strauss, managing director at Innovation Protocol (a marketing consulting & design agency). Strauss shared his brand strategy tips in the TFA webinar Building a Fermented Brand. He stressed fermented brands need to avoid getting stuck in the “scientific nuance of how you make your products. I’m not saying delete the science, just don’t make it the marquee.”

Alex Corsini, founder of frozen pizza company Alex’s Awesome Sourdough (and TFA Advisory Board member) agrees. Corsini, who moderated the webinar, says he began his brand with a heavy emphasis on the science of fermenting sourdough.

“Our customer didn’t really respond to that. And that’s something I see in fermentation all too often, is people aren’t selling the actual benefit. They want to understand the benefit, so that’s what you lead with,” Corsini advises.

If you’re selling kombucha, for example, share that it’s a feel-good product that will make you feel better than a soda, Corsini says. Don’t make your selling pitch the SCOBY’s technical specifications.

Teach, Don’t Sell

“I don’t understand fermentation. I don’t understand the health benefits. I don’t understand its cultural origins. I don’t understand what section to buy it in. I don’t understand what to eat it with or who to serve it too. Your first duty as a brand is to help me make sense of this, help me understand it,” Strauss says. “It’s not your job to be the sexiest, raciest, the most innovative, it’s your job to help me understand. And where understanding sits in the consumer’s mind is where buying behaviors originate. So the first and most important duty of your brand is to simply help me not feel alone, help me not feel confused, help me not feel overwhelmed.”

By educating the consumer, by inspiring them to learn about fermentation, “they will be indelibly connected to you,” Strauss continues. “They will prefer you. They won’t wonder if your price is a penny cheaper, they’ll prefer you because you’re who they learned from. We buy who we learn from.”

There’s not enough room on a label to detail all the health benefits or the scientific details of a product. But this information can go on a brand’s website, social media page or table-top display at a trade show or farmer’s market.

“I hope that your audience doesn’t hear from you just once,” Strauss says. They should find a video of your product on Instagram, find recipes on your website and see an ad in the local paper. Brands need to create multiple opportunities to engage, “don’t try to cram all of your value in a single channel.”

A New Economy

The COVID-19 pandemic has permanently changed the economy. Consumer lifestyles have changed, too, and these new behaviors create opportunities, especially for fermented products that are healthy and flavorful.

“Historically, if you were trying to build a consumer packaged goods brand, it was really about your resume, your long list of accomplishments , your heritage in farming, your understanding of the chemistry and that was what marked the person, the business, the brand,” Strauss says. “But actually now, it’s really about how you resonate, how I connect with you, how you inspire me, and that doesn’t require a long history, that requires a contemporary participation.”

“In a world where the audience is starting and ending their search digitally, each of the things that you share, post, write about, blog about, video dialogue about, those things are little breadcrumbs that will never go away,” Sasha says. “They’re little trails that lead to your brand, lead to your resources, lead to your understanding and this is powerful.”

Consumers rejected traditional brand loyalties this past year. They’re increasingly open to new brands, curious about new cultural flavors and want healthy food. Critically, Strauss points out, they want to purchase from socially responsible brands. “In a post-covid era, we want a brant to also do good,” he says.

Producers must make conscious choices about the farmers they use — how are they improving soil health? What is the environmental impact of their distribution line?

“Understand you have to make an impact, somehow do good for the world while building business,” Strauss says.

- Published in Business

The “New Normal”for CPG Companies

Don’t expect people immediately to dump their sourdough starters and crowd restaurants when the Covid-19 pandemic is over. In a U.S. consumer trends survey, 42% of people said they plan to cook more at home post-pandemic. This news is great for Consumer Packaged Goods (CPG) brands.

From record sales to supply shortages to new safety regulations, the retail grocery business was changed dramatically by the pandemic in 2020. But CPG companies experienced phenomenal growth: sales rose over 10% — more growth in one year than in the four-year period from 2016 to 2019. Though pandemic stockpiling (fingers crossed) likely will not recur in 2021 , CPG sales show no signs of slowing down. A mere 7% of Americans said they’d cook less after the pandemic than before. Consumers are buying CPGs more than ever. And they’re not staying loyal to their favorite brands — over 50% of respondents said that they are willing to try different products, and 66% of them stuck with those new brands.

Fermented CPG brands are in a great spot to take advantage of these trends. Healthy foods gained significant share in the food market in 2020. The pandemic propelled fermented food and beverage into the spotlight. More Americans began experimenting with healthier eating during the pandemic, and now they’ve adopted it as a habit.

What does this mean for the future of CPG brands? Here are four ways they must adapt to the “new normal”:

- Sales via Multiple Channels

Consumers won’t be shopping for your products only in brick-and-mortar stores. More consumers than ever are buying through ecommerce. Digital grocery sales were a niche category before the pandemic — now, CPG food and beverage sales are estimated to top $100 billion in 2021.

Food and beverage sales became the largest CPG online segment in 2020.

Direct-to-consumer (DTC) sales also shifted into high gear. Consumers turned to DTC during the pandemic to get their favorite products straight from the manufacturer. Good examples are kombucha producers selling bottles directly from the brewery and a sauerkraut maker shipping to consumers from their kitchen. An analysis by Retail Dive found direct-to-consumer businesses during the pandemic fared better than did traditional brick-and-mortar retailers.

But this doesn’t mean CPG brands should abandon selling in grocery stores.

According to Deloitte’s 2021 Consumer Product Industry Outlook, four out of five companies say “resetting their go-to-market strategy is critical to meeting their objectives; however, only half rated the current maturity of their related capabilities as high.” A majority of CPG companies surveyed say a bigger online and omnichannel presence will be a means of reaching consumers in 2021.

- Conscious Consumption

Consumers want to buy from brands that care about social and environmental issues. Societal inequality and environmental impact are big concerns to many consumers, and they are spending their dollars on ethical brands willing to put their money where their mouth is.

Deloitte found nine in 10 consumers say the pandemic is “an opportunity for large companies to hit ‘reset’ and focus on doing right by their workers, consumers, communities and the environment.” The CPG companies surveyed agree — three in four say establishing such initiatives in 2021 are a “strategy to place purpose alongside profit, express corporate values, and address heightened consumer attention to sustainability, social justice, equality, and environmental consciousness.”

Authenticity is key for proper brand activism. CPG companies need to be transparent with their consumers, integrating their social and environmental purposes into all parts of their business and organization. A brand that acts inconsistently will quickly lose trust with a consumer.

- Preference for Small Producers

CPG sales during the pandemic showed an interesting dichotomy: large companies had the highest dollar growth, but small companies – taken as a whole – gained meaningful share of market. A report by business consulting firm McKinsey & Company found market share of small companies during the pandemic increased from 18.2% in 2019 to 19.2% in 2020, while midsize businesses were flat and large companies fell from 51.2% to 50.5%.

More consumers did switch to new brands during the pandemic, but their primary reason was availability. This area is one where large brands have an advantage, as their greater resources should help them keep products on grocery store shelves.

- Supply Chain Improvements

Whether implementing new safety rules, finding sources with available products or switching packaging materials, every CPG brand had to adjust their supply chain in 2020. They are acting quickly to fix weaknesses exposed by the pandemic, and nine in 10 say they’re making significant progress.

CPG companies used to be praised for holding minimal inventories, but 2020 tested their resilience. Deloitte’s report explains: “Resilience is how companies keep their supply chains from breaking and restore them quickly when they do. It is also how they can gain the nimbleness and scalability to power new go-to-market approaches and innovative business models.”

Barb Renner, Deloitte’s vice chairman and U.S. leader of consumer products, says one of the biggest problems identified in their survey was an over-reliance on a small number of vendors. Most companies didn’t have backup plans. “If they were getting their product from a handful of vendors and one of those vendors had to close down, did they try to find an alternative source?” she asked.

CPG executives indicated supply chain resilience is important or very important for the company in 2021, with nine in 10 saying they are investing in improvements. Beyond creating reliable supply chains that can support their production, CPG companies need to be able to respond to demand and shift supply to new locations.

- Published in Business

Ugly Delicious

A unique business practice has been developed in Montana by Farmented Foods — the company ferments discarded produce from local growers to fill their jars with the likes of radish kimchi, dill sauerkraut and spicy carrot chips. The co-owners (Vanessa Walsten and Vanessa Williamson) met in 2016 at a Farm to Market class at Montana State University. They are currently getting ready to renovate a former cafe into a fermentation kitchen, thanks to a grant from the Montana Agriculture Development Council.

“Every year, so much produce is wasted because we don’t deem it perfect enough,” says Williamson, adding that the company “was founded initially to help farmers eliminate unnecessary food loss on their farms in the form of ugly and excess crops.”

They estimate they’ve saved over 6,000 pounds of imperfect produce.

Read more (Daily Inter Lake)

- Published in Business