Hard Seltzer from Whey?

A professor of food science at Cornell University has launched a unique food product: a hard seltzer made from yogurt byproduct.

The seltzer, Norwhey, started as part of an academic research project by food scientist Sam Alcaine, who works in the Fermentation Lab at Cornell’s College of Agriculture and Science. It all began in 2016 when the New York Department of Environmental Conservation asked Cornell to solve a problem. The state, the largest producer of yogurt in the country, was concerned with the large amount of waste (whey) being thrown away. For every one cup of yogurt made, three cups of byproduct are produced.

That amounts to a huge amount of waste, with up to a billion pounds of whey produced each year just in the state of New York, Alcaine told Good Beer Hunting. The article notes that Greek yogurt producer Chobani alone generates 50 truckloads of whey per day.

“There is a lot of lactose floating out there, and I wanted to find out how we could ferment that in new and novel ways,” Alcaine said.

Historically, whey has been considered worthless since it contains no protein. But It does still have the vitamins found in milk — calcium, potassium, zinc, magnesium and vitamin B5— which spurred Alcaine to research how why could be made into something of value.

“In the brewing world, we’ve always looked for developing better-for-you products,” said Alcaine, who co-founded Denver’s Doc Luces Brewery and worked in new product development at Miller Brewing Company. “It’s been kind of a hard space to play in, with alcohol. So this is an opportunity. We just have to make it taste good.”

“There are actually some old stories around that, in Iceland, they would take the whey from skyr [a cultured dairy product similar to curd cheese] and they would put it into these barrels,” Alcaine said in a Cornell press release on Norwhey. “It would age and it would become alcohol. But it hadn’t been done in my lifetime.”

Norwhey is made by adding the enzyme lactase to whey, which breaks lactose into glucose and galactose. These sugars are then fermented traditionally.

Alcaine partnered with Trystan Sandvoss, founder of First Light Creamery and then Marketing Director at Old Chatham Creamery, to create Norwhey. The pair entered a food and agriculture competition, Grow-NY, in 2020, and made it to the final round. That same year, they secured $50,000 in funding from the FuzeHub Commercialization Competition, and used the prize money to test batches and can and label products at New York-based Meier’s Creek Brewing.

Norwhey was first available at retail in April at New York-based Wegmans grocery stores. The hard seltzer is currently offered inthree flavors: Glacial Ginger, Solar Citrus and Mountain Berry, all with an ABV of 4%. There are plans to open a taproom and to experiment with new flavors this summer.

Cornell notes Norwhey is a “triple threat.” The alcoholic drink has a better nutritional profile than beer, it recycles waste material and “it could eventually act as a model for dairy farmers looking for additional revenue.”

For his part, Alcaine says he does not want to quit his day job and become a business owner. He wants to remain a professor and a researcher. But he’s hoping people will copy his idea, building “a whey-based economy in New York” and a more sustainable yogurt industry globally.

Alt Protein Hype Missing Bigger Food Industry Solution

Will alternative proteins save the planet? A report by the International Panel of Experts on Sustainable Food Systems (IPES-Food) says alt proteins – or what they call “lab meat” – aren’t the answer. In a new report, these experts say major reforms need to be put in place to increase biodiversity of food, improve access to better nutrition and limit Big Food’s control over the food system.

Companies, governments and investors are turning to alternative proteins as a way to feed a rapidly growing population but, the panel notes, they don’t address the world hunger crisis.

“In reality they lead us back to the same problems of our industrial food system: giant agribusiness firms, standardized diets and industrial supply chains that harm people and the planet,” announces a video created by IPES-Food. “We need to change the system, not the product.”

Adds Phil Howard, lead author of the report: “It’s easy to see why people would be drawn to the marketing and hype, but meat techno-fixes will not save the planet. In many cases, they will make the problems with our industrial food system worse — fossil fuel dependence, industrial monocultures, pollution, poor work conditions, unhealthy diets, and control by massive corporations. Just as electric cars are not a silver bullet to fix climate change, these solutions are not going to fix our damaging industrial food system..”

The report suggests that, to feed a growing population, the food industry should focus on sustainable food systems, not a transition to alternative proteins. A healthy food system should be regional, nutritious and focused on how real food is produced.

Read more (IPES-FOOD)

- Published in Business

Zero Waste with Fermentation Techniques

Paste Magazine highlights the fermentation philosophy of Chef David Porras, who operates the Oak Hill Café and Farm. The hyper-local site, a 2020 James Beard semi-finalist for Best New Restaurant, operates in Greenville, South Carolina, on a 2.4-acre farm.

Porras’ kitchen, according to the magazine, “looks like an alchemist’s workroom, jars and tubs of experimental pickling, emulsions and infusions dotting the counter.”

“I was always interested in learning about fermentation. Fermentation is a flavor — you can use it for cooking just like lime or lemon juice,” he said.

The restaurant’s menu reflects a true farm-to-table approach. They use permaculture (sustainable agriculture planning to mimic nature) to keep the farm at peak fertility to grow healthy produce. By fermenting instead of trashing unused food, they’ve reduced 50% of their food waste.

“We try to be zero waste by applying fermentation techniques as well as drying, infusion, teas, powders and compost tea,” he said.

Read more (Paste Magazine)

- Published in Food & Flavor

Mastering Indoor Mushroom Farming

After four decades of research, brothers from Copenhagen have developed a method to reliably cultivate morel mushrooms indoors, year-round, in a climate-controlled environment. Morels typically grow for only a few months in the spring in finicky, woodland locations. They also sell for a high price.

Jacob and Karsten Kirk, 64-year-old twins, yielded 20 pounds per square yard of morels in last year’s crop. Karsten said: “the cost per square meter for producing a morel will be roughly the same as producing a white button mushroom.” They call their efforts the Danish Morel Project and they’re still figuring out how to commercialize it.

Kenneth Toft-Hansen, a Danish chef and winner of the 2019 Bocuse d’Or, notes if the Kirk brothers are able to master sourcing morels widely and affordably, “it will be a game changer for the food industry.”

Read more (The New York Times)

- Published in Food & Flavor

Tastier Non-Alcoholic Beer

Though non-alcoholic drinks are growing in popularity, alcohol-free beer has been a laggard. These brews lack the flavorful aroma of hops, with the resulting beverage flat and watery.

Mimicking beer’s flavor profile has been challenging for brewers hoping to appeal to dry drinkers. Some producers add aroma hops in the final stages of brewing, but it’s expensive and wasteful.

“When you remove the alcohol from the beer, for example by heating it up, you also kill the aroma that comes from hops. Other methods for making alcohol-free beer by minimizing fermentation also lead to poor aroma because alcohol is needed for hops to pass their unique flavor to the beer,” says Sotirios Kampranis, a professor in University of Copenhagen’s department of plant and environmental sciences who led the research.

Now researchers from the university have found a possible solution. Their innovation uses baker’s yeast that’s grown in fermenters and releases an aroma of hops. Results of their study were published in the journal Nature.

“After years of research, we have found a way to produce a group of small molecules called monoterpenoids, which provide the hoppy-flavor, and then add them to the beer at the end of the brewing process to give it back its lost flavor. No one has been able to do this before, so it’s a game changer for non-alcoholic beer,” Kamprani says. “When the hop aroma molecules are released from yeast, we collect them and put them into the beer, giving back the taste of regular beer that so many of us know and love. It actually makes the use of aroma hops in brewing redundant, because we only need the molecules passing on the scent and flavor and not the actual hops,” explains Kampranis.

Sustainable Solution

Their discovery represents a potential breakthrough for the overall beer industry because, researchers point out, it could improve beer’s sustainability.

Aroma hops require an enormous amount of water. Over 713 gallons are needed to grow one kilogram of hops. And sourcing fresh hops involves a carbon-heavy supply chain. Hops are farmed mainly on the U.S. West Coast, so trucks and refrigeration units are needed for transportation .

By using baker’s yeast, researchers can create a hoppy flavor without wasting gallons of water and creating carbon emissions.

“With our method, we skip aroma hops altogether and thereby also the water and the transportation. This means that one kilogram of hops aroma can be produced with more than 10.000 times less water and more than 100 times less CO2,” Kampranis says. “Long term, we hope to change the brewing industry with our method – also the production of regular beer, where the use of aroma hops is also very wasteful.”

Kampranis and colleague Simon Dusséaux plan to have the process ready for the brewing industry by this October. The two have founded the biotech company EvodiaBio.

- Published in Food & Flavor, Science

The Trending Nordic Diet

For nearly two decades, the Mediterranean diet has been the food choice recommended by dietitians and the USDA.. This approach to eating has been proven to improve health and reduce risk of chronic disease.

But there’s a new contender: the Nordic diet.

This plan focuses on eating fermented foods and beverages, with less meat and more legumes than in the Mediterranean diet. Both approaches are plant-based and full of lean proteins, complex carbs and healthy fats.

“The nordic diet really does promote a lifelong approach to healthy eating,” says Valerie Agyeman, RDN (pictured). “It also really really focuses on seasonal, local, organic and sustainably sourced whole foods that are traditionally eaten in the Nordic region.”

Agyeman, founder of Flourish Heights, shared her research during a Today’s Dietitian webinar “Breaking Down the Nordic Diet: Why is it Gaining So Much Popularity?” The presentation was designed to help registered dietitians better counsel clients on healthy eating habits.

What is Nordic Eating?

The diet embraces traditional Nordic cuisine, with a focus on ingredients that are fresh and local. The core of the fare is from Sweden, Norway, Denmark, Finland and Iceland.

“Fresh, pure and earthly are the words used to describe this food movement that was born out of the landscape and culture,” Agyeman says. “The Nordic movement is all about using what is available.”

The goal is not to invent a new cuisine, but to get back to its roots. Seafood is central, but meat – scarce during the long Nordic winters – is treated as a side dish Fresh vegetables and berries – the most common Nordic fruit – are prevalent during the summer. Fermented foods were born out of the necessity to preserve food from the warmer months to eat during winter. The indigenous Nordic people traditionally fermented vegetables, fish and dairy.

“It really takes the focus off calories and puts it on healthy food,” Agyeman adds. “This way of eating is pretty nutrient-dense.”

Nordic foods, she continues, are served in their natural state with minimal processing. They’re high in antioxidants, prebiotics, probiotics, fiber, minerals and vitamins; low in saturated fats, trans fats, added sugars and added salts.

“The Nordic diet is really not that straightforward,” Agyeman says. “When you think of other cuisines, like Italian cuisine, they have signature flavors and various culinary techniques that make up Italian cuisine. When it comes to Nordic cooking, it’s very diverse.”

Sustainability

Key, too, is sustainability. Foods from the Nordic countries have a lower environmental impact because they’re sourced locally and eaten in season.

Sustainability is also partly why Nordic cuisine has become a staple at many restaurants. The farm-to-table style continues to expand in restaurant dining, along with fermentation. Restaurants around the world are following the lead of Copenhagen’s Noma and building their own labs to explore the flavors and textures fermentation adds to dishes.

“Today [fermentation] is not something that’s needed,” like it was before a global food scene made it simpler to eat fresh food year round, Agyeman says. “But culinary wise, fermentation has evolved. It’s become a big part of these new creations.”

Fermented foods and beverages add to the “epicurean experience,” adds Dr. Luiza Petre, a cardiologist and nutrition expert based in New York.

“Savory flavors and fermented food with spices make it a culinary experience,” she says.

Health Benefits

Studies show eating the Nordic diet prevents obesity and reduces the risk of cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, high blood pressure and high cholesterol.

The health effects of the Nordic diet were always assumed to be solely due to weight loss. But results of the most recent study of the diet, published in the journal Clinical Nutrition in February, found the positive health effects are “irrespective of weight loss.”

“It’s surprising because most people believe that positive effects on blood sugar and cholesterol are solely due to weight loss. Here, we have found this not to be the case. Other mechanisms are also at play,” said Lars Ove Dragsted, of the University of Copenhagen’s Department of Nutrition, Exercise and Sports in a statement on the study.

The researchers from Denmark, Finland, Norway, Sweden and Iceland studied 200 people over 50 years of age with elevated BMI. All were at an increased risk of diabetes and cardiovascular disease. For six months, the group ate the Nordic diet while a control group ate their regular meals.

“The group that had been on the Nordic diet for six months became significantly healthier, with lower cholesterol levels, lower overall levels of both saturated and unsaturated fat in the blood, and better regulation of glucose, compared to the control group,” Dragsted said. “We kept the group on the Nordic diet weight stable, meaning that we asked them to eat more if they lost weight. Even without weight loss, we could see an improvement in their health.”

- Published in Health

Upcycling Olive Oil, Wine & Beer Byproducts

The olive oil, wine and beer industries each create an enormous amount of waste. Producers, vintners, and brewers dispose of millions of tons of pomace and spent grains every year, often at a big cost.

To a crowd of food industry professionals at Natural Products Expo West, professors at University of California, Davis, shared their research into how these byproducts can be upcycled.

“There’s a lot of waste that can be generated doing agriculture and food processing,” said Selina Wang, PhD, Cooperative Extension Specialist in the Food, Science and Technology department. Globally, good waste is estimated at 140 billion tons a year. “That is a lot, but also a lot of opportunities for us to explore.”

Olive Oil Waste

Wang, who researches small-scale fruit and vegetable processing, says olive oil needs a byproduct solution. Oil is only 20% of an olive’s weight – the other 80% is discarded in olive oil production. Globally, the industry generates 20-30 million tons of olive pomace a year.

What industry, Wang questions, would operate using only 20% of their commodity?

“This is an industry that has been made to use the minor product. But we know there’s a lot of values in the byproduct,” Wang says. Olive pomace has numerous active health compounds which, when consumed, are proven to prevent disease like cancer, Type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease. But disposing of this byproduct creates a large carbon footprint. “Can we have a solution to climate change while at the same time improving our health?”

Many producers use the waste as animal feed, giving it away to ranchers. But often, the cost of transportation is too high to justify the benefits. And using olive pomace for compost is not ideal, as it has a negative effect on soil microbes.

In a recent UC Davis study, olive pomace was added to pasta, bread and granola bars, which were then tested for consumer acceptance. Tastes were strong and the grains turned purple when the pomace was added, so the amount of pomace added was low (7% in the pasta and 5% in the bread and granola bars). Consumers didn’t hate the products – they liked them slightly less than the unfortified versions – but the majority said they wouldn’t pay more for the items made with olive pomace.

“I would challenge us to think outside the status quo,” Wang says. “Olive oil was an industry developed with tradition, love and passion. But does it make sense to have an industry where we’re using only 20% of raw material? Or do we actually have an industry focusing on the 80% and the 20% is a wonderful gift we give to family and friends?”

Grape Waste

Further UC Davis studies are also looking at wine byproducts The global wine industry produces 10-13 million tons of grape pomace annually.

That waste is rich in flavonoids and oligosaccharides. UC Davis and Iowa State are currently studying the flavonoids as natural antioxidants and the oligosaccharides as prebiotics, and if they would have a synergetic effect on gut health.

“It basically shows there’s a second life to winemaking and the wine byproduct that’s generated,” she said.

Researchers at UC Davis who have studied feeding cows seaweed to reduce greenhouse gas emissions have proposed to the California Research Dairy Foundation that they use grape pomace instead. It’s cheaper than seaweed and cows burp less after consuming grapes.

Other industries, such as cosmetics, pet food and construction, could also use the byproducts. For example, a new study shows how construction companies could use olive pomace in asphalt paving and building materials.

Brewing Waste

Waste streams are an even bigger problem for the brewing industry, says Glen Fox, PhD, the Anheuser-Busch endowed professor of Malting and Brewing Science at UC Davis. Brewers globally produce over 49 million tons of spent grain a year.

That waste is high in water content (about 80%), but most brewers don’t have the ability to store wet grain. Similar to olive and grape pomace, it’s cheap feed for animals. But the cost of transporting spent grain outweighs the benefits for most breweries.

“At the moment, they’re giving it away,” he says. “They would like to get something back for it.”

Fox sees big opportunities for food producers to use brewing grains, which are packed with nutrients. Compounds can be extracted, such as dietary fiber for supplements, hydrocinnamic acid for makeup and even cellulose pulp for toilet paper. Fox is working on a patent for a process that would allow grains to be applied directly to soil.

The craft brewing industry is “the most viral business in America,” Fox said. There are breweries everywhere – some 9,000 craft brewers in the U.S., with over 1,000 in California alone. But there are not nearly as many food production facilities that can collect the spent grains.

“This industry is in an advantageous position because it has that waste stream every day,” Fox says. “If you want to potentially use this in your business, you don’t have to look far for your supplier.”

When Will the Food Industry Innovate?

“We have to start rethinking our food systems – farm to mouth,” Fox said. “It’s a big challenge.”

There’s no shortage of high-quality research on options for olive oil, wine and beer byproducts, Wang points out. The food industry needs to innovate profitable, desirable products made from upcycled ingredients. At one point whey – a byproduct of cheese production – was dumped down the drain, Wang said. Now it’s a popular protein supplement, in powders and bars.

Two brands are making inroads. Vine to Bar uses grape pomace to make chocolate. ReGrained uses spent beer grains to make pastas, bars and puffs.

“The key is we need to go from a linear economy – which is just made to waste – to a circular economy where we can avoid generating these wastes by upcycling every waste or every byproduct that we generate,” Wang said.

Q&A with Local Culture

In a food industry where greenwashing is common, Local Culture Live Ferments doesn’t pad their sales sheets with faux environmental fluff. Sustainability is core to their business practices.

“I never want to stray away from the connections with our farmers. I never want to stray away from the quality of our ferments,” says Chris Frost-McKee, director of operations for the Northern California-based vegetable fermenter. Sauerkraut is their top seller. “We take a lot of pride from the fact that we don’t ferment in plastic. We are doing our part to be as plastic-free as possible and leave the smallest footprint that we can.”

The company began as a passion project of Chris’ sister, Sarah. She recruited her brother, a home fermenter since his early 20s, and they envisioned creating two Local Culture fermentation hubs on the west coast — one where Sarah lives, in Bend, Ore., and a second in Grass Valley, Calif., Chris’ home. True to their name, they wanted to ferment with local produce. But, with the colder climate in Central Oregon cutting Bend’s growing season short, this proved impossible.

“In Grass Valley, we’re able to source cabbage eight miles from our facility, eight months out of the year. We’ve created partnerships where every year the farm is planting more and more acreage for us, rotating their cover crops. It’s a beautiful thing, it’s real regenerative farming,” Chris says. And Sarah is now creating a separate project, fermented salad dressings, under the Super Belly Ferments brand.

Local Culture started as a farmers market side hustle, but Chris and his business partners (wife Cristina and friend Elissa Wolf Blank, pictured with Chris) dove into scaling the business in 2020. They’re now in over 100 grocers in the west, including Whole Foods. Though sales boomed during the pandemic, 2022 is shaping to be their biggest year. At the recent Expo West, Local Culture was one of 40 brands selected by food distributor KeHe for the exclusive “Golden Ticket” at their TrendFinder Event This designation fast-tracks small businesses into KeHe’s product portfolio, giving them exposure to over 30,000 retail locations.

Below is a Q&A with Chris Frost-McKee, who spoke with The Fermentation Association on the Expo West show floor.

TFA: Congrats on the KeHe “Golden Ticket” win! What are you going to have to change about scaling?

Chris Frost-McKee: The tricky thing with scaling the way that we do, our fermenters are stainless steel, variable capacity fermenters. We currently have 66 of them. We’ll need to get more as we scale, but they’re only sold once a year during wine making season. They ship them over from Italy. So that presents difficulties for sure. Producing in the same size fermenters, that’s part of the integrity we’re going to keep, that’s very important to me. We ferment for a minimum of 4-6 weeks in a very regulated, temperature-controlled environment. That really helps with the consistency of our product.

We are also keeping the values the same with our farmers, making sure they can scale while staying sustainable. We’re scaling up our acreage with our main farmer next year. They rotate three successions of a summer variety of cabbage for us and then one succession of winter storage. And with those four successions, we can work about eight months directly with them, never going into cold storage.

You just returned from a planning meeting with the local farm that supplies your cabbage. Tell me more about the farmers you work with.

CFM: We’re trying to only work farmer direct. One of our closest connections is the farm Super Tuber. They are Nevada City-based. They focus on regenerative farming practices and they focus on staple root crops and cabbage. So from the very beginning, as we first started with these smaller products, we started buying cabbage from them. Twice a year we sit down with them with the planting planning: What do you think it’s going to look like this year? How many plugs on your side can you plant for us?

Super Tuber is really into this idea and I love it — they harvest in reusable bins in the field, then bring them straight to us in reusable bins. When you work with farms, produce comes in paraffin or wax boxes. Those go straight in the landfill. We are trying to have as little waste as possible. We’d love to never receive anything in wax boxes, and we’re there about 95% of the time. We compost everything that comes out of the kitchen.

Another thing, the cabbage isn’t wrapped in plastic packaging. We peel off the outer cabbage leaves as we prep in the kitchen. Those outer leaves are what I like to layer on top to seal everything. It weighs the ferment batch down and provides a nice layer if there’s ever an impurity — which really doesn’t happen — so if we ever discard anything, it’s those top leaves that would normally get composted.

What was the biggest turning point for your brand to go from selling at farmer markets to getting in stores?

CFM: Honestly, as corporate as Whole Foods is, they have a wonderful way of supporting small brands. The west coast is filled with small ferment companies trying so hard and not succeeding at getting in. Whole Foods saw potential in us. That was really the turning point for our company. And they’ve continued to be loyal to us. Not all chains are pleasant to work with, but we made big moves through Whole Foods. It opened up this door to the Bay Area independents, like the Good Food Mercantile and the Good Food Awards. The Bay Area independents are so cutting edge in a way that I think a lot of these big chains strive to be as far as the products that they bring in and the diversity they really search for in craft products. At this point, we’re almost everywhere in the greater Bay Area that we’ve set out to be in — and I do think that started with getting in Whole Foods in 2020.

TFA: How were you distributing before that?

CFM: We were driving all over Northern California. We would drive five hours round trip to drop off like 10 cases of kraut. It did not make sense long term. Now we work with Tony’s Fine Foods to distribute to the pacific region. Tony’s has been supportive from the beginning.

We still self distribute locally, but only whatever we can do in a 20 minutes drive. The local support that we have, that started with our stands at the farmers market and then our storefront, that support has been amazing. Like we honestly sell more in our local co-op then we do in 40 stores in the Pacific Northwest. That kind of local support will always be there.

TFA: That’s great that you have a big local fan base.

CFM: When we decided to get going in Grass Valley, we opened up a store front for a year-and-a-half and had this really great interface with our community. We were really experimental in those years. That was the year I was coming up with a lot of small batches. When we were invited to be in the Whole Foods, we had to move to a distributor and palletize. Things were not so small batch anymore. Right as the pandemic hit, we started being received really well in the west coast. We streamlined the products that people really wanted. We’ve got our favorite line of krauts, our different kimchis. We still do a lot of hot sauces and brine tonics.

TFA: What is your favorite flavor?

CFM: Turmeric Ginger Jalapeno is my go-to, everyday. My body craves it. Our Beet Fennel though outsells anything we carry. People love it.

TFA: You’ve gone from fermenting in your home kitchen to distributing regionally. What do you think has been your biggest lesson in all of this?

CFM: Not giving up. Listening to the ferments — it sounds really weird, but I literally have studied patterns in the life within the fermenters. For example, we have these variable capacity lids that have an airlock on the top where the brine can spit out. In certain ebbs and flows, I think it’s astrological, all the fermenters will come to life, no matter how old they are. Or in a certain cycle of the moon, all of them will compact and leave an air pocket that I have to reset. It is crazy, witnessing the nature and patterns.

Through all the trial and error and discouragement, it’s the life of the microbiology itself that is really the inspiring thing. I could never get it right, it’s always going to be different no matter what. But I’m getting a lot better at creating that perfect environment for consistency. If you ask me — I’m living and breathing it because I digest this all the time.

TFA: Where do you see the future of fermentation?

CFM: I see it growing. It is beyond all the trends, it’s something that’s been around for ages, for centuries, and there’s a reason why it’s always been incorporated in our diets. There’s this sense of awakening that so many people in the mainstream are feeling — if it’s kombucha, if it’s sauerkraut, if it’s kefir, if it’s yogurt — people are really feeling the benefits. The pandemic has had a huge influence on that, too. I think everyone in grocery would agree fermentation is a big thing right now and it deserves to be a big thing.

- Published in Business, Food & Flavor

Microbial Farmers

An article in Modern Farmer highlights “the new generation of microbial farmers,” scientists using microbes to replace chemical additives in food.

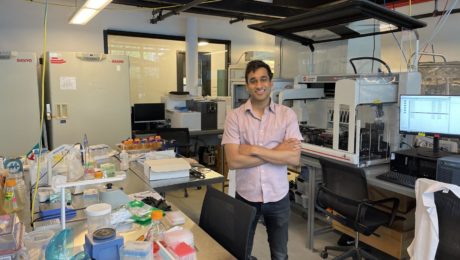

At Kingdom Supercultures, co-founders Ravi Sheth (pictured) and Kendall Dabaghi have developed natural microbial strains that mimic additives “instead of having a library of artificial chemicals.” Scientists at the company use machine learning to explore millions of “uncharacterized microbes that live inside fermented food. They extract microbial strains, merge them with other isolates and design what they call ‘supercultures.’”

The end results are healthier compounds with flavors, textures and functional properties similar to their artificial – and less healthy – counterparts. Since the company launched in 2020, they’ve made additives for plant-based cheese and yogurt, vegan personal care products and a vegan butter exclusive to Eleven Madison Park restaurant in New York.

Read more (Modern Farmer)

- Published in Business

Expo West Returns

In March 2020, Natural Products Expo West became one of the first casualties in the U.S. events world, shut down by the outbreak of Covid-19 even as booths were being set up in Anaheim. Now, two years later, Expo West returns to Orange County with natural food exhibitors from around the world. TFA staff and advisory board members will also be in attendance.

In 2019, the enormous spring trade show attracted around 88,000 registrations; this year, that number is estimated at 55,000-60,000. Show producer New Hope Network (part of London-based Informa PLC) is also including a virtual option for attendees still unable or unwilling to travel.

The trends at this year’s event are being driven by Millennial and Gen Z consumers. New Hope put a spotlight on six top themes in a recent webinar:

No. 1: Functional Ingredients. “Health and wellness products make up a quarter of the volume of the industry but represent two-thirds of all growth,” said SPINS Data Analyst Scott Dicker. “We’re seeing consumers pushing for individual pursuit of wellness across channels.”

No. 2: Organic & Regenerative. Food that focuses on performance nutrition, food made with ashwagandha or food with paleo ingredients are driving growth for organic and regenerative products. Sodas and carbonated beverages are also helping organic products grow, “one of the last ‘junk food’ categories penetrated by natural and organic,” Dicker said. Gut health sodas, especially.

No. 3: Climate and Sustainability. Media headlines are declaring carbon as the new calorie. Consumer surveys speak to that — 70% will pay more for “premium, sustainable, climate-friendly products” and 80% want brands to educate them on their roles in climate issues. Companies are changing ingredient sources and product packaging to be more environmentally-friendly.

No. 4: Diversity. “Over the past couple years, we’ve seen tremendous growth in women, minority, NGLCC (National LGBT Chamber of Commerce) certified and veteran-owned businesses and you’re going to see it all over the show floor,” Dicker said.

No. 5: Plant-Based Innovation. Plant-based eating has skyrocketed over the last five years. “But plant-based alone isn’t enough anymore. What are plant-based brands doing to keep up with innovation?” Dicker said.

No. 6: Sustainable Meat & Dairy. Though the sustainable meat and dairy category is down 2.1%, pockets of it are growing, specifically grass-fed, fair trade and animal welfare and sustainability claims. Innovations are coming from small and local farms.

Read more (New Hope Network)

- Published in Business, Food & Flavor