Yogurt Alters Gut Microbiome

It’s widely appreciated that consuming high-quality yogurt can aid a healthy diet. Now new research shows eating yogurt changes the composition of the human gut microbiome.

In a new human study published in BMC Microbiology, researchers studied the microbiome of European twins. Results found those regularly eating yogurt had less visceral fat mass, reduced insulin levels and an increase of bacterial species in the gut. Strains S. thermophilus, B. animalis subsp. lactis., S. thermophilus and B. animalis subsp. lactis were all present in yogurt eaters.

The study also found the yogurt bacteria are “transient members of the gut microbiome and do not durably engraft within the gut lumen.”

Read more (BMC Microbiology)

The Rise of Fermented Foods and -Biotics

Microbes on our bodies outnumber our human cells. Can we improve our health using microbes?

“(Humans) are minuscule compared to the genetic content of our microbiomes,” says Maria Marco, PhD, professor of food science at the University of California, Davis (and a TFA Advisory Board Member). “We now have a much better handle that microbes are good for us.”

Marco was a featured speaker at an Institute for the Advancement of Food and Nutrition Sciences (IAFNS) webinar, “What’s What?! Probiotics, Postbiotics, Prebiotics, Synbiotics and Fermented Foods.” Also speaking was Karen Scott, PhD, professor at University of Aberdeen, Scotland, and co-director of the university’s Centre for Bacteria in Health and Disease.

While probiotic-containing foods and supplements have been around for decades – or, in the case of fermented foods, tens of thousands of years – they have become more common recently . But “as the terms relevant to this space proliferate, so does confusion,” states IAFNS.

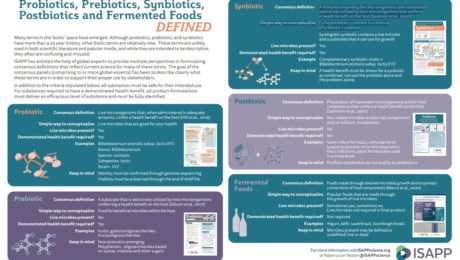

Using definitions created by the International Scientific Association for Postbiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP), Marco and Scott presented the attributes of fermented foods, probiotics, prebiotics, synbiotics and postbiotics.

The majority of microbes in the human body are in the digestive tract, Marco notes: “We have frankly very few ways we can direct them towards what we need for sustaining our health and well being.” Humans can’t control age or genetics and have little impact over environmental factors.

What we can control, though, are the kinds of foods, beverages and supplements we consume.

Fermented Foods

It’s estimated that one third of the human diet globally is made up of fermented foods. But this is a diverse category that shares one common element: “Fermented foods are made by microbes,” Marco adds. “You can’t have a fermented food without a microbe.”

This distinction separates true fermented foods from those that look fermented but don’t have microbes involved. Quick pickles or cucumbers soaked in a vinegar brine, for example, are not fermented. And there are fermented foods that originally contained live microbes, but where those microbes are killed during production — in sourdough bread, shelf-stable pickles and veggies, sausage, soy sauce, vinegar, wine, most beers, coffee and chocolate. Fermented foods that contain live, viable microbes include yogurt, kefir, most cheeses, natto, tempeh, kimchi, dry fermented sausages, most kombuchas and some beers.

“There’s confusion among scientists and the public about what is a fermented food,” Marco says.

Fermented foods provide health benefits by transforming food ingredients, synthesizing nutrients and providing live microbes.There is some evidence they aid digestive health (kefir, sourdough), improve mood and behavior (wine, beer, coffee), reduce inflammatory bowel syndrome (sauerkraut, sourdough), aid weight loss and fight obesity (yogurt, kimchi), and enhance immunity (kimchi, yogurt), bone health (yogurt, kefir, natto) and the cardiovascular system (yogurt, cheese, coffee, wine, beer, vinegar). But there are only a few studies on humans that have examined these topics. More studies of fermented foods are needed to document and prove these benefits.

Probiotics

Probiotics, on the other hand, have clinical evidence documenting their health benefits. “We know probiotics improve human health,” Marco says.

The concept of probiotics dates back to the early 20th century, but the word “probiotic” has now become a household term. Most scientific studies involving probiotics look at their benefit to the digestive tract, but new research is examining their impact on the respiratory system and in aiding vaginal health.

Probiotics are different from fermented foods because they are defined at the strain level and their genomic sequence is known, Marco adds. Probiotics should be alive at the time of consumption in order to provide a health benefit.

Postbiotics

Postbiotics are dead microorganisms. It is a relatively new term — also referred to as parabiotics, non-viable probiotics, heat-killed probiotics and tyndallized probiotics — and there’s emerging research around the health benefits of consuming these inanimate cells.

“I think we’ll be seeing a lot more attention to this concept as we begin to understand how probiotics work and gut microbiomes work and the specific compounds needed to modulate our health,” according to Marco.

Prebiotics

Prebiotics are, according to ISAPP, “A substrate selectively utilized by host microorganisms conferring a health benefit on the host.”

“It basically means a food source for microorganisms that live in or on a source,” Scott says. “But any candidate for a prebiotic must confer a health benefit.”

Prebiotics are not processed in the small intestine. They reach the large intestine undigested, where they serve as nutrients for beneficial microorganisms in our gut microbiome.

Synbiotics

Synbiotics are mixtures of probiotics and prebiotics and stimulate a host’s resident bacteria. They are composed of live microorganisms and substrates that demonstrate a health benefit when combined.

Scott notes that, in human trials with probiotics, none of the currently recognized probiotic species (like lactobacilli and bifidobacteria) appear in fecal samples existing probiotics.

“There must be something missing in what we’re doing in this field,” she says. “We need new probiotics. I’m not saying existing probiotics don’t work or we shouldn’t use them. But I think that now that we have the potential to develop new probiotics, they might be even better than what we have now.”

She sees great potential in this new class of -biotics.

Both Scott and Marco encouraged nutritionists to work with clients on first improving their diets before adding supplements. The -biotics stimulate what’s in the gut, so a diverse diet is the best starting point.

Glenn Gibson Early Career Researcher Prize

Applications are being accepted for the 2022 Glenn Gibson Early Career Researcher Prize, sponsored by the International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP). The winner will receive $1,500 U.S. cash and an invitation to present at the 2022 ISAPP annual meeting. Click here for application details, due Nov. 19.

In 2021, ISAPP launched the Early Career Researcher Prize. As this initiative was spearheaded by ISAPP co-founder and longtime board member Prof. Glenn Gibson, this award was renamed to honor him: “Glenn Gibson Early Career Researcher Prize”. The intent of this award is to recognize excellence in research in early career researchers in the fields of probiotics, prebiotics, synbiotics, postbiotics or fermented foods.

- Published in Science

Dairy Alternative from Fermented Pea & Rice

Researchers have discovered a milk alternative: fermenting pea and rice with probiotic strains. This dairy-free mixture is highly digestible and has the same animal protein as found in milk, casein.

Fermentation was critical to the results. Plant-based proteins are poorly digested because they are often insoluble in water, explains Professor Monique Lacroix of Institut National de la Recherche Scientifique (INRS). Animal proteins, in contrast, “usually take the form of elongated fibers that are easily processed by digestive enzymes.” But lactic acid bacteria in the fermented pea and rice drink predigested the proteins, improving digestibility.

“Fermentation allowed for the production of peptides (protein fragments) resulting from the breakdown of proteins during fermentation, facilitating their absorption during digestion,” notes an article on the research in Nutrition Insight.

INRS partnered with probiotics company Bio-K+ on the research. Their findings were published in the Journal of Food Science.

Read more (Nutrition Insight)

- Published in Science

Can Gut Microbes Fight Viruses?

An estimated 40 trillion microbes make up our gut microbiome. Researchers are now studying how these microbes protect our immune system, fighting off viruses like Covid-19.

“Imagine microbes that block a virus from entering a cell or communicate with the cell and make it a less desirable place for the virus to set up residence,” says Mark Kaplan, chair of the department of microbiology and immunology at the Indiana University School of Medicine. “Manipulating those lines of communication might give us an arsenal to help your body fight the virus more effectively.”

These microbes, according to an article in National Geographic, may fight viruses in one of three ways: “building a wall that blocks invaders, deploying advanced weaponry and providing support to the immune system.” Kaplan calls intestinal bacteria “the gatekeepers between what we eat and our body.”

The article details the new, innovative measures medical professionals are taking to repair a patient’s damaged gut microbiome — transplanting fecal matter, administering a bacteria-targeting virus and pills that release antiviral interferons. But the most compelling way may be consuming a diet rich in fermented foods — the article notes a consensus among medical and science professionals that fermented foods can promote a healthy microbiome.

Read more (National Geographic)

Fermentation vs. Fiber — Both Help, but Fermentation Shines

A diet high in fermented foods increases microbiome diversity, lowers inflammation, and improves immune response, according to researchers at Stanford University’s School of Medicine.The groundbreaking results were published in the journal Cell.

In the clinical trial, healthy individuals were fed for 10 weeks, a diet either high in fermented foods and beverages or high in fiber. The fermented diet — which included yogurt, kefir, cottage cheese, kimchi, kombucha, fermented veggies and fermented veggie broth — led to an increase in overall microbial diversity, with stronger effects from larger servings.

“This is a stunning finding,” says Justin Sonnenburg, PhD, an associate professor of microbiology and immunology at Stanford. “It provides one of the first examples of how a simple change in diet can reproducibly remodel the microbiota across a cohort of healthy adults.”

Researchers were particularly pleased to see participants in the fermented foods diet showed less activation in four types of immune cells. There was a decrease in the levels of 19 inflammatory proteins, including interleukin 6, which is linked to rheumatoid arthritis, Type 2 diabetes and chronic stress.

“Microbiota-targeted diets can change immune status, providing a promising avenue for decreasing inflammation in healthy adults,” says Christopher Gardner, PhD, the Rehnborg Farquhar Professor and director of nutrition studies at the Stanford Prevention Research Center. “This finding was consistent across all participants in the study who were assigned to the higher fermented food group.”

Microbiota Stability vs. Diversity

Continues a press release from Stanford Medicine News Center: By contrast, none of the 19 inflammatory proteins decreased in participants assigned to a high-fiber diet rich in legumes, seeds, whole grains, nuts, vegetables and fruits. On average, the diversity of their gut microbes also remained stable.

“We expected high fiber to have a more universally beneficial effect and increase microbiota diversity,” said Erica Sonnenburg, PhD, a senior research scientist at Stanford in basic life sciences, microbiology and immunology. “The data suggest that increased fiber intake alone over a short time period is insufficient to increase microbiota diversity.”

Justin and Erica Sonnenburg and Christopher Gardner are co-authors of the study. The lead authors are Hannah Wastyk, a PhD student in bioengineering, and former postdoctoral scholar Gabriela Fragiadakis, PhD, now an assistant professor of medicine at UC-San Francisco.

A wide body of evidence has demonstrated that diet shapes the gut microbiome which, in turn, can affect the immune system and overall health. According to Gardner, low microbiome diversity has been linked to obesity and diabetes.

“We wanted to conduct a proof-of-concept study that could test whether microbiota-targeted food could be an avenue for combatting the overwhelming rise in chronic inflammatory diseases,” Gardner said.

The researchers focused on fiber and fermented foods due to previous reports of their potential health benefits. High-fiber diets have been associated with lower rates of mortality. Fermented foods are thought to help with weight maintenance and may decrease the risk of diabetes, cancer and cardiovascular disease.

The researchers analyzed blood and stool samples collected during a three-week pre-trial period, the 10 weeks of the diet, and a four-week period after the diet when the participants ate as they chose.

The findings paint a nuanced picture of the influence of diet on gut microbes and immune status. Those who increased their consumption of fermented foods showed effects consistent with prior research showing that short-term changes in diet can rapidly alter the gut microbiome. The limited changes in the microbiome for the high-fiber group dovetailed with previous reports of the resilience of the human microbiome over short time periods.

Designing a suite of dietary and microbial strategies

The results also showed that greater fiber intake led to more carbohydrates in stool samples, pointing to incomplete fiber degradation by gut microbes. These findings are consistent with research suggesting that the microbiome of a person living in the industrialized world is depleted of fiber-degrading microbes.

“It is possible that a longer intervention would have allowed for the microbiota to adequately adapt to the increase in fiber consumption,” Erica Sonnenburg said. “Alternatively, the deliberate introduction of fiber-consuming microbes may be required to increase the microbiota’s capacity to break down the carbohydrates.”

In addition to exploring these possibilities, the researchers plan to conduct studies in mice to investigate the molecular mechanisms by which diets alter the microbiome and reduce inflammatory proteins. They also aim to test whether high-fiber and fermented foods synergize to influence the microbiome and immune system of humans. Another goal is to examine whether the consumption of fermented foods decreases inflammation or improves other health markers in patients with immunological and metabolic diseases, in pregnant women, or in older individuals.

“There are many more ways to target the microbiome with food and supplements, and we hope to continue to investigate how different diets, probiotics and prebiotics impact the microbiome and health in different groups,” Justin Sonnenburg said.

Other Stanford co-authors are Dalia Perelman, health educator; former graduate students Dylan Dahan, PhD, and Carlos Gonzalez, PhD; graduate student Bryan Merrill; former research assistant Madeline Topf; postdoctoral scholars William Van Treuren, PhD, and Shuo Han, PhD; Jennifer Robinson, PhD, administrative director of the Community Health and Prevention Research Master’s Program and program manager of the Nutrition Studies Group; and Joshua Elias, PhD.

Researchers from the nonprofit research center Chan-Zuckerberg Biohub also contributed to the study. Here’s the complete press release from Stanford Medicine News Center.

Supplements vs. Fermented Foods

Two UCLA professors of medicine encourage people “rather than thinking in terms of supplements, add some fermented foods to your diet.” In a Q&A, the doctors say the popularity of probiotics, postbiotics and the gut microbiome has blurred their value, despite the plethora of reputable scientific research. Product manufacturers — as has happened before, with terms like “gluten-free” — have begun labelling everything as containing -biotics or benefitting the gut microbiome.

“The word probiotics refers to the beneficial microbes found in certain fermented foods and beverages, as well [as] in specially formulated nutritional supplements,” write UCLA doctors Eve Glazier and Elizabeth Ko. “That means that any fermented food that contains or was made by live bacteria contains postbiotics. … Initial findings suggest that postbiotics may play a role in maintaining a balanced and robust immune system, support digestive health and help to manage the health of the gut microbiome.”

Read more (Journal Review)

- Published in Science

Kefir Brands Respond

The kefir brands recently tested for their probiotic claims are challenging the results.

In May, a study found 66% of commercial kefir products overstated probiotic counts and “contained species not included on the label.” The Journal of Dairy Science Communications published the peer-reviewed work by researchers at the University of Illinois and Ohio State University.

“Based on the results…there should be more regulatory oversight on label accuracy for commercial kefir products to reduce the number of claims that can be misleading to consumers,” reads the study. “Classification as a ‘cultured milk product’ by the FDA requires disclosure of added microorganisms, yet regulation of ingredient quality and viability need to be better scrutinized. All 5 kefir products guaranteed specific bacterial species used in fermentation, yet no product matched its labeling completely.”

Researchers tested two bottles of each of five major kefir brands: Maple Hill Plain Kefir, Siggi’s Plain Filmjölk, Redwood Hill Farm Plain Goat Milk Kefir, CoYo Kefir and Lifeway Original Kefir. Bottles were measured for microbial count and taxonomy to validate label claims.

The Fermentation Association reached out to the five brands involved and asked for their responses to the results. Redwood Hill and Lifeway both submitted detailed statements. Maple Hill, Siggi’s and CoYo did not return multiple requests for comment.

Probiotic Count

Probiotics in fermented products are listed in colony-forming units (CFUs), and the study found kefir from both Lifeway and Redwood Hill contained fewer CFUs than what was claimed on the label. But these brands — who send their products to third-party labs for testing — said the results are not accurate.

Lifeway refutes the assertion that their Original Kefir did not meet the claimed probiotic count. Lifeway references U.S. Food and Drug Administration food labeling laws, which dictate that a product “must provide all nutrient and food component quantities in relation to a serving size.” Lifeway’s label on their 32-ounce bottle says that the serving size of kefir is 1 cup, making the claim of 25-30 billion CFUs per serving size accurate.

The study results, Lifeway notes in their statement, were “premised upon an erroneous assumption that Lifeway claims it has 25-30 billion CFUs per gram” rather than per serving size.

“The authors’ flawed assumption is perhaps a result of their lack of familiarity with FDA labeling requirements or a result of merely overlooking the details in order to support their intended conclusions going into the testing,” reads a statement from Lifeway.

In fact, Lifeway points out, the study’s “erroneous conclusion premised upon the flawed assumption…actually proves the accuracy of Lifeway’s claim of 25-30 billion CFUs per (8 ounce) serving.”

Redwood Hill Farm, too, refutes the study’s conclusion. Their Goat Milk Kefir currently includes the phrase “millions of probiotics per sip” on its label. The label referenced in the study was an old version that claimed “hundreds of billions” of probiotics, which was discontinued last year. According to Redwood Hill Farm, that old label was based on third-party testing that confirmed hundreds of billions of CFUs per 8-ounce serving. But careful review of the kefir’s probiotic counts in 2019-2020 found some CFUs in the hundreds of billions and others in the tens of billions. Redwood Hill changed their label to millions rather than billions “to be absolutely sure that we could meet our target claim on a consistent basis.”

Variation in CFU counts is common in traditional plating testing techniques. Redwood Hill referenced a study published in Nutritional Outlook that found that plating results can vary 30-50%.

“Given the challenges around probiotic CFU enumeration, we were not too surprised to see a discrepancy between the number of CFUs in our Goat Milk Kefir found in the study and our past analyses,” reads the statement from Redwood Hill Farm. “Like all living organisms, probiotics are challenging to control and measure. A particular microorganism’s ability to reproduce is impacted by a variety of factors, including temperature, oxygen level, variations in the nutrient composition of the milk, and pH level. Our kefir has a sixty-day shelf life and during that time the different types of bacteria in the product will peak and die-off in relation to the conditions those particular bacteria like. For example, fermented dairy products naturally become more acidic (lower pH) as they age and while some bacteria thrive in acidic environments, others’ reproduction is stunted. This makes the exact CFU count rather volatile not only from bottle to bottle, but also throughout the timespan between when that bottle leaves our facility and when it expires.”

Redwood Hill Farm’s most recent testing measured 400 million CFUs per gram or 96 billion per serving (1 cup). These figures compare with what the study found — 193 million CFUs per gram or 46 billion per serving.

“Although the University of Illinois study found only half the probiotic cells that our study did, this is actually not that wide of a variation in bacteria reproduction based on all of the conditional factors outlined above,” their statement reads.

Species Count

The study’s test results found all kefir brands contained species not on the label. Lifeway notes their culture claims are based on the time of manufacture, not on expiration date. “Moreover, the authors validate that all of the claimed culture species except for the bifidos, Leuconostoc and L. reuteri, (which could be at a low concentration due to time of shelf-life), were identified in their testing,” reads Lifeway’s statement.

Redwood Hill Farm says that, based on the study results (that “2 Lactobacillus delbrueckii subspecies or 3 Lc. lactis subspecies could not be identified” in their kefir), they are pursuing further analysis. They’ve contacted their culture supplier for further insight, and are sending new samples to a third-party lab.

“These cultures are at the heart of the product and are what transforms the goat milk into a yogurt drink with its characteristic thick and creamy texture and tart flavor,” reads the Redwood Hill Farm statement. “It’s difficult to understand how these core active agents in the kefir could not be present in the product at any stage in its lifecycle.”

DNA vs. Plating Methodology

The study utilized both DNA sequencing and traditional plating methodologies, even though plating testing alone is considered the industry standard for kefir. Plating testing for kefir is done in a microbiology laboratory where it’s incubated to determine bacteria colony growth.

The study itself notes: “Limitation of DNA-based sequencing methods could explain why taxa stated on labels were not detected and why unclaimed viable species were identified.”

Lifeway points out: “This concession as to testing limitations is critical to note as it is but one explanation of many as to why various species may have not been detected. First and foremost, the authors fail to validate the DNA extraction method to establish that it delivers all the available DNA in the type of dairy product analyzed; for example, they do not appear to have broken down the calcium bonds. Further, they appear to not have undertaken the required extra enzymatic treatments. Moreover, for their microanalysis, they are using MRS [a method for cultivation of lactobacilli] but only incubating for 48 hours. As most kefir products would contain a significant amount of Lactococci, there is a high chance of not detecting this species unless you go to 72 hours of incubation. Another unknown important factor in the testing is the time period within the cycle of the shelf-life of the product that was tested. This is critical as the longer the product sits on a shelf, the fewer number of live and active bacteria will be present.”

Meanwhile, Redwood Hill Farm says “our team will continue to educate ourselves on the application of DNA sequencing technology to fermented food product probiotic count analysis and what opportunities and limitations this methodology may offer versus traditional plating techniques.”

- Published in Science

What’s the Actual Probiotic Count of Commercial Kefir?

A new peer-reviewed study from researchers at the University of Illinois and Ohio State University found 66% of commercial kefir products overstated probiotic count and “contained species not included on the label.”

Kefir, widely consumed in Europe and the Middle East, is growing in popularity in the U.S. Researchers examined the bacterial content of five kefir brands. Their results, published in the Journal of Dairy Science, challenge the “probiotic punch” the labels claim.

“Our study shows better quality control of kefir products is required to demonstrate and understand their potential health benefits,” says Kelly Swanson, professor in human nutrition in the Department of Animal Sciences and the Division of Nutritional Sciences at the University of Illinois. “It is important for consumers to know the accurate contents of the fermented foods they consume.”

Probiotics in fermented products are listed in colony-forming units (CFUs). The more probiotics, the greater the health benefit.

According to a news release from the University of Illinois: “Most companies guarantee minimum counts of at least a billion bacteria per gram, with many claiming up to 10 or 100 billion. Because food-fermenting microorganisms have a long history of use, are non-pathogenic, and do not produce harmful substances, they are considered ‘Generally Recognized As Safe’ (GRAS) by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and require no further approvals for use. That means companies are free to make claims about bacteria count with little regulation or oversight.”

To perform the study, the researchers bought two bottles of each of five major kefir brands. Bottles were brought to the lab where bacterial cells were counted and bacterial species identified. Only one of the brands studied had the amount of probiotics listed on its label.

“Just like probiotics, the health benefits of kefirs and other fermented foods will largely be dependent on the type and density of microorganisms present,” Swanson says. “With trillions of bacteria already inhabiting the gut, billions are usually necessary for health promotion. These product shortcomings in regard to bacterial counts will most certainly reduce their likelihood of providing benefits.”

The news release continues:

When the research team compared the bacteria in their samples against the ones listed on the label, there were distinct discrepancies. Some species were missing altogether, while others were present but unlisted. All five products contained, but didn’t list, Streptococcus salivarius. And four out of five contained Lactobacillus paracasei.

Both species are common starter strains in the production of yogurts and other fermented foods. Because those bacteria are relatively safe and may contribute to the health benefits of fermented foods, Swanson says it’s not clear why they aren’t listed on the labels.

Although the study only tested five products, Swanson suggests the results are emblematic of a larger issue in the fermented foods market.

“Even though fermented foods and beverages have been important components of the human food supply for thousands of years, few well-designed studies on their composition and health benefits have been conducted outside of yogurt. Our results underscore just how important it is to study these products,” he says. “And given the absence of regulatory scrutiny, consumers should be wary and demand better-quality commercial fermented foods.”

Defining Postbiotics

As postbiotics continue to trend among consumers, the International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) released a consensus definition on the category, published in Nature Reviews: Gastroenterology & Hepatology.

The panel of international experts that created the definition made it clear that postbiotics and probiotics are fundamentally different. Probiotics are live microorganisms; postbiotics are non-living microorganisms. The published definition states that postbiotics are a: “preparation of inanimate microorganisms and/or their components that confers a health benefit on the host.”

Inactive Microorganisms

A postbiotic could be whole microbial cells or components of cells, “as long as they have somehow been deliberately inactivated,” according to the news release by ISAPP. And a postbiotic does not need to be derived from a probiotic.

“With this definition of postbiotics, we wanted to acknowledge that different live microorganisms respond to different methods of inactivation,” says Seppo Salminen, professor at the University of Turku and the lead author of the definition. “Furthermore, we used the word ‘inanimate’ in favor of words such as ‘killed’ or ‘inert’ because the latter could suggest the products had no biological activity.”

The definition has been in the works for almost two years by authors from various disciplines in the probiotics and postbiotics fields. These include: gastroenterology, pediatrics, metabolomics, functional genomics, cellular physiology and immunology.

“This was a challenging definition to settle,” says Mary Ellen Sanders, ISAPP’s Executive Science Officer. “There are some who think that any purified component from microbial growth should be considered to be a postbiotic, but the panel clearly felt that purified, microbe-derived substances, for example, butyrate or any antibiotic, should just be called by their chemical names. We are confident we captured the essential elements of the postbiotic concept, allowing for many innovative products in this category in the years ahead.”

Growing Scientific Interest

Sanders continues: “The definition will be a touchstone for scientists, both in academia and industry, as they work to develop products that benefit host health in new ways. We hope this clarified definition will be embraced by all stakeholders, so that when the term ‘postbiotics’ is used on a product, consumers will know what to expect.”

Postbiotics have been on the market in Japan for years, and fermented infant formulas with added postbiotics are sold commercially in South America, the Middle East and in some European countries. ISAPP, in a release, notes: “Given the scientific groundswell, postbiotic applications are likely to expand quickly.”

The definition is the latest in a series of international consensus definitions by ISAPP. These include: probiotics, prebiotics, synbiotics and fermented foods.

- Probiotics: Live microorganisms that, when administered in adequate amounts, confer a health benefit on the host.

- Prebiotics: A substrate that is selectively utilized by host microorganisms conferring a health benefit.

- Synbiotics: A mixture comprising live microorganisms and substrate(s) selectively utilized by host microorganisms that confers a health benefit on the host.

- Fermented foods: Foods made through desired microbial growth and enzymatic conversions of food components.

- Published in Science