Solving Illnesses with Fermentation?

Scientists in Russia and Egypt have developed a functional drink that’s been proven to combat anemia and malnutrition. The juice is made from beet extract, milk and probiotic bacterial strains. The scientists developed a quinoa bread, too. The goal is to keep the beverage and bread affordably priced and get them offered at grocery stores internationally.

“One should bear in mind that we are not creating a medicine, but a natural, functional food product,” said Sobhi Ahmed Azab Al-Suhaimi, professor in the Department of Technology at South Ural State University (SUSU) in Russia. “However, this juice can make up for the lack of iron, zinc, manganese and calcium in the body. One serving of the drink will contain the whole rate [sic] of minerals. Its carbohydrate content is low. Fermented juice will help to overcome anemia and to improve digestion due to probiotics.”

Scientists at SUSU worked with scientists at the University of Alexandria in Egypt. Their findings were published in the Journal of Food Processing and Preservation and Plants.

Read more (Phys.org)

Cautionary Notes about Probiotics

Do probiotic supplements deliver the same benefits as fermented foods? Dr. Gail Cresci says to be leery of prebiotic and probiotic pills.

“There are challenges to keeping microbes viable in encapsulated tablets,” says Cresci, director of Nutrition Research for the Cleveland Clinic’s Department of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition. “It’s also very, very important to know that each strain of bacteria is not the same as the next. For example, lactobacillus has hundreds of different strains, and each one may behave differently. People like to use supplements because they like to think one size fits all, but it doesn’t.”

“Take in prebiotics and probiotics through food sources. Yogurt with added probiotic bacterial strains is much better to consume than supplements also because as it’s been waiting for you to eat it, it’s been producing more beneficial metabolites. When you eat it, you get all that.”

Read more (American Heart Association/U.S. News & World Report)

The New Definition of Fermented Food

After Dr. Bob Hutkins finished a presentation on fermented foods during a respected nutrition conference, the first audience question was from someone with a PhD in nutrition: “What are fermented foods?”

“I thought ‘Doesn’t everyone know what fermentation is?’ I realized, we do need a definition. Those of us that work in this field know what we’re talking about when we say fermented foods, but even people trained in foods do not understand this concept,” says Hutkins, a professor of food science at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. He presented The New Definition of Fermented Foods during a webinar with TFA.

Hutkins was part of a 13-member interdisciplinary panel of scientists that released a consensus definition on fermented foods. Their research, published this month in Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology, defines fermented foods as: “foods made through desired microbial growth and enzymatic conversions of food components.”

“We needed a definition that conveyed this simple message of a raw food turning into a fermented food via microorganisms,” Hutkins says. “It brings some clarity to many of these issues that, frankly, people are confused about.”

David Ehreth, president and founder of Alexander Valley Gourmet, parent company of Sonoma Brinery (and a TFA Advisory Board member), agreed that an expert definition was necessary.

“As a producer, and having started this effort to put live culture products on the standard grocery shelf, I started doing it as a result of unique flavors that I could achieve through fermentation that weren’t present in acidified products,” Ehreth says. “Since many of us put this on our labels, we should be paying close attention to what these folks are doing, since they are the scientific backbone of our industry.”

Hutkins calls fermented foods “the original shelf-stable foods.” They’ve been used by humankind for over thousands of years, but have mushroomed in popularity in the last 15. Fermented foods check many boxes for hot food trends: artisanal, local, organic, natural, healthy, flavorful, sustainable, innovative, hip, funky, chic, cool and Instagram-worthy.

Nutrition, Hutkins hypothesizes, is a big driver of the public’s interest in fermentation. He noted that Today’s Dietitian has voted fermented foods a top superfood for the past four years.

Evidence to make bold claims about the health benefits of fermentation, though, is lacking. Hutkins says there is observational and epidemiological evidence. But randomized, human clinical trials — “the highest evidence one can rely on” — are few and small-scale for fermented foods.

Hutkins shared some research results. One study found that Korean elders who regularly consume kimchi harbor lactic acid bacteria (LAB) in their GI tract, providing compelling evidence that LAB survives digestion and reaches the gut. Another study of cultured dairy products, cheese, fermented vegetables, Asian fermented products and fermented drinks found that most contain over 10 million LAB per gram.

Still, the lack of credible studies is “a barrier we have to get past,” Hutkins says. There are confirmed health benefits with yogurt and kefir, but this research was funded by the dairy industry, a large trade group with significant resources.

“I think there’s enough evidence — most of it through these associated studies — to warrant this statement: fermented foods, including those that contain live microorganisms, should be included as part of a healthy diet.”

Are Fermented Foods Probiotics?

Probiotics and fermented foods are not equivalent, says Mary Ellen Sanders, PhD and executive science officer of the International Scientific Association of Probiotics & Prebiotics (ISAPP). She advises fermented food producers that don’t meet the criteria of a probiotic to use descriptors such as “live active cultures” or “fermented food with live microbes” on their labels rather than “probiotic.”

“There are quite a few differences between probiotics and many fermented foods. You cannot assume a fermented food is a probiotic food even if it has live cultures present,” says Sanders. She highlighted her 30 years worth of insight into the field during a TFA webinar, Are Fermented Foods Probiotics?

Some fermented foods do meet these criteria, such as some yogurts and cultured milks that are well-studied. But many traditional fermented foods do not.

Using multiple peer-reviewed scientific studies and conclusion from expert panels in the fields of probiotics and fermented foods, Sanders shared the ways in which fermented foods and probiotics differ:

- Health benefits

By definition, a probiotic must have a documented health benefit. Many fermented foods have not been tested for a health benefit.

“If you are interested in recommending health benefits from a fermented food in an evidence-based manner, many traditional fermented foods fall short. They don’t have the controlled randomized trials that will provide a causal link between the food and the health benefit,” she says. “A food may be nutritious, but probiotic benefits must stem from the live microbe, not the nutritional composition of the food. Otherwise you just have a nutritious food that happens to have live microorganisms in it. You don’t have a probiotic food.”

- Quality studies

In her presentation, Sanders shared multiple randomized clinical trials on human subjects with supported health evidence for probiotics. But there are few randomized, controlled studies on fermented foods. Most are cohort studies, which inherently have a higher risk of bias and cannot provide a causal link between consuming fermented foods and a health benefit.

“A strong hypothesis is not the same as proof,” Sanders says. “Evidence for probiotics must meet a higher standard than small associative studies, many of which are tracking biomarkers and not health endpoints.”

She noted, though, there are some studies on fermented milk and yogurt that show a conferred health benefit.

- Strain designation

Though many fermented foods do have live microbes, a probiotic is required to be identified to the strain level. The genus and species should also be properly named according to current nomenclature. Many fermented foods contain undefined microbial composition. Without that strain designation, one can’t tie the scientific evidence on that strain to the probiotic product.

- Microbe quantity

Another key differentiator is that probiotics must be delivered at a known quantity that matches the amount that results in a health benefit. Probiotics are typically quantified in colony forming units (or CFUs).

“A probiotic has a known effective dose. But fermented foods often contain unknown levels of microbes, especially at time of consumption,” Sanders says.

What Can Brands Do?

If food brands keep using the word probiotics as a catch-all to describe a fermented product, the term will lose its utility. Using “probiotics” on food with unsubstantiated proof of probiotics is a misuse of the term.

“When I see a fermented food that says probiotics on it, I very often think what they’re trying to communicate on that label [is that it] contains live microbes,” Sanders says, “because I’m doubting, at least some of the products I see, that they have any evidence of a health benefit. And so they’re just looking for a catchy, single word that will communicate to people that this has live microbes in it. ‘Live active cultures’ is something that resonates with people as well. So why not use that?”

Sanders encourages fermented brands to standardize the terms “live active cultures,” “live microbes,” “live microorganisms” or “fermented food with live microbes.” For products pasteurized after fermentation, there’s a term for them too: “Made with live cultures.”

Controlled human studies on fermented foods can be challenging, Sanders admits. Such studies can be difficult to properly blind, since placebos for foods are hard to design. The fermentation process affects the product taste so that study subjects may know what they are consuming. But the health benefits of fermented foods could be studied, though. She also advises producers to focus on the nutritional value of their food.

“That’s one thing that really has me excited about this concept of core benefits,” says Maria Marco, PhD, professor of food science and technology at University of California, Davis (and a member of TFA’s Advisory Board) and moderator of the webinar. “I think it kind of opens the doors to the possibility of fermented fruits and vegetables where there’s certain organisms, microorganisms that we’d expect to be there but again we need to know really if those microorganisms are needed to make those foods healthy.”

New Fermented Coffee & Tea Drinks

Researchers from the National University of Singapore (NUS) have created new fermented coffee and tea drinks. These drinks, invented by a professor and two doctoral students, are being labeled as “probiotic coffee and tea drinks that are packed with gut-friendly live probiotics.” They claim that the drinks can be stored for three months without altering the probiotics.

“Coffee and tea are two of the most popular drinks around the world, and are both plant-based infusions. As such, they act as a perfect vehicle for carrying and delivering probiotics to consumers. Most commercially available probiotic coffee and tea drinks are unfermented. Our team has created a new range of these beverages using the fermentation process as it produces healthy compounds that improve nutrient digestibility while retaining the health benefits associated with coffee and tea,” explained NUS Associate Professor Liu Shao Quan.

Read more (Science Daily)

Pandemic Spurs Fermented Beverages

The coronavirus continues to drive sales of fermented drinks. Lifeway’s kefir, Farmhouse Culture’s kraut juice, Probitat’s fermented planted-based smoothies, Flying Ember’s hard kombucha and Buoy Hydration’s fermented drinks all report increased sales as consumers take a bigger interest in the immune-enhancing benefits of fermented beverages.

“As demand ramps up for immune-enhancing products, manufacturers have an opportunity to innovate with immune-supporting ingredients and flavors,” says Becca Henrickson, marketing managed of Wixon, a flavor and seasoning company. “When flavoring beverages with immune support ingredients, selecting flavors that increase or complement a product’s health perception is optimal.”

Read more (Food Business News)

New Strains Drive Probiotic Market

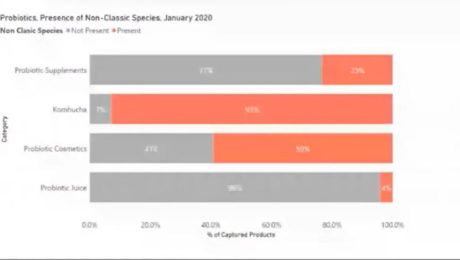

Kombucha and cosmetics are driving growth in the probiotic and prebiotic markets by making products that use non-classic strains of bacteria.

The e-commerce market for probiotic supplements was estimated at $973 million across 20 countries in 2020. America accounts for almost half of those sales. Ewa Hudson, director of insights for Lumina Intelligence, shared this info at the Probiota Americas 2020 Conference. (Lumina and Probiota Americas are parts of William Reed Business Media, the parent company for FoodNavigator.com.) The session, New Horizons for Prebiotics & Probiotics, included Lumina’s insight into non-classic bacteria strains and a panel discussion with leaders in the probiotics field.

In 2020, 32% of all probiotics in America — and 41% of the best-selling ones — contained non-classic species. Hudson said this species classification is a messy space, especially from a consumer’s perspective, because there are so many species. Kombucha includes the most non-classic probiotic species — of those products with probiotics, 93% include non-classic bacteria .

Most products with probiotics include one of the four common bacteria species: lactobacilli, bifidobacterium, bacillus and saccharomyces. Lumina excluded these four from their research to focus on the growth of the non-classic probiotic strains. These include: streptococcus thermophilus, kombucha culture, lactococcus lactis, bifida ferment lysate, enterococcus faecium, streptococcus salivarius, clostridium butyricum and streptococcus faecalis.

Though probiotics are often used in supplements, more fermented food and beverage manufacturers are using probiotic strains in their products, especially in the growing alternative protein market.

Synbiotics are also becoming more widely used; the study found synbiotics were the most prevalent formulate in probiotics. Synbiotics are a combination of both prebiotics and postbiotics. A synbiotic ensures that probiotics will have a food source in the gut.

(Probiotics are live microorganisms, friendly bacteria that provide health benefits. Probiotics can be found in fermented food and taken as supplements. Prebiotics are dietary fibers that feed the probiotics. Postbiotics are an emerging concept in the “biotics” space — postbiotics are the waste byproduct of probiotics.)

“With probiotics, we are really only starting to scratch the surface with the development of synbiotics,” says Jens Walter, PhD, professor of ecology, food and the microbiome at APC Microbiome Ireland.

The new generation of probiotics will depend on strains that are “efficacious in the gut,” Walter noted.

“If you look into the probiotic market, most of the lactobacillus species — and also species like bifidobacterium lactis — are not inherent organisms of the human gut. We’re using a lot of organisms that I would argue have an ecological disadvantage in the gut,” Walter says. “If you’re talking about next generation probiotics, I think what will become is we are looking for the key players in the gut, specifically key players that are underrepresented or linked to certain benefits, and then we are trying to put them back in the ecosystem.”

It’s challenging to find a prebiotic or postbiotic that is precise, he continues.

“Every human has a distinct microbiome. So it’s likely a synbiotic designed for one human may not be as functional in another human,” Walter says. “The opportunities here are tremendous.”

Daniel Ramon Vidal, vice president of research and development and health and wellness at the American food processing company Archer-Daniels-Midland (ADM), also spoke. He noted that the human body is made up of trillions of microbial cells, but we know little about these microbial worlds.

“There is an enormous amount of possibilities to isolate new strains that are living in our body,” Daniels says. “We need as much science as possible, that’s my message”

The panel agreed that postbiotics has become one of the next great concepts that scientists, manufacturers and gastroenterologists have latched onto. But consumers are not as familiar with postbiotics as they are with probiotics and prebiotics , notes Justin Green, PhD, director of scientific affairs for EpiCor, a postbiotic ingredient produced by Cargill.

“This causes more confusion, so I think that’s going to be another interesting aspect of postbiotics — both the identity of what postbiotics are and how it confers its benefits and (how that will be) communicated to the consumer,” Green says.

New Global Definition for Fermented Foods

A major scientific announcement was made this week, creating a global definition for fermented foods. A team of 13 interdisciplinary scientists (including TFA Advisory Board members Maria Marco and Ben Wolfe) spent over a year discussing the issue in order to reach a consensus. An official definition has long been debated, especially in recent years as fermentation has experienced a renaissance in the modern diet. This definition, the first of its kind, hopes to provide clarity to scientists, producers and consumers.

Below is a press release from the International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) on the definition. The full research paper was published in Nature. Marco also wrote a blog on the ISAPP website, further detailing the work that led to the definition.

Humans have consumed different types of fermented foods — from kimchi to yogurt — for thousands of years. Yet only recently, with the availability of new scientific techniques for analyzing their nutritional properties and microbiological composition, have scientists begun to understand exactly how the unique flavors and textures are created and how these foods benefit human health.

Now, 13 interdisciplinary scientists from the fields of microbiology, food science and technology, family medicine, ecology, immunology, and microbial genetics have come together to create the first international consensus definition of fermented foods. Their paper, published in Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology, defines fermented foods as: “foods made through desired microbial growth and enzymatic conversions of food components”.

The authors take care to note the difference between probiotics and the live microbes associated with fermented foods. The word ‘probiotic’, they say, only applies in special cases where the fermented food retains live microorganisms at the time of consumption, and only when the microorganisms are defined and shown to provide a health benefit, as demonstrated in a scientific study.

“Many people think fermented foods are good for health — and that may be true, but the scientific studies required to prove it are limited and have mainly focused on certain fermented food types,” says first author Maria Marco, Professor in the Department of Food Science and Technology at the University of California, Davis.

Co-author Bob Hutkins, Professor in the Department of Food Science and Technology at University of Nebraska, Lincoln — who has authored a well-known academic textbook on fermented foods — says, “We created this definition to cover the thousands of different types of fermented foods from all over the world, as a starting point for further investigations into how these foods and their associated microbes affect human health.”

The consensus panel discussion was organized in 2019 by the International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP), a non-profit organization responsible for the published scientific consensus definitions of both probiotics (in 2014) and prebiotics (in 2017).

Mary Ellen Sanders, Executive Science Officer of ISAPP, says, “To date, different people have had different ideas of what constitutes a fermented food. The new definition provides a clear concept that can be understood by the general public, industry members and regulators.”

Currently, evidence for the positive health effects of fermented foods has relied more on epidemiological and population-based studies and less on randomized controlled trials. The authors expect that, in the years ahead, scientists will undertake more hypothesis-driven research on how different fermented foods from around the globe — derived from dairy products, fruit, vegetables, grains, and even meats — affect human physiology and enhance human health.

Probiotics Top Trending Ingredient Category

Probiotics are still a top trending ingredient. In the U.S., 62% of consumers say they would be “extremely or very open” to using products with probiotics.

– BuzzBack Innovation Insight

- Published in Business, Food & Flavor

What Fermenters Need to Know About Probiotics Regulations

Probiotics are the third most popular health product ingredient, with 62% of American consumers buying or wanting to buy them. However, only one-third of consumers say they understand probiotics. That confusion is evident in the courts, where consumer class action lawsuits are continually filed against probiotic food and beverages.

Meanwhile, the probiotics industry is pushing to update 25-year-old dietary supplement laws, there’s a new head of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the lactobacillus taxonomy has been overhauled.

What does all this mean for fermented food and beverage brands? Ivan Wasserman, an attorney with expertise in foods and dietary supplements, says now is the time to plan for legal roadblocks, whether a new product or an existing brand. Wasserman shared his legal expertise during a Natural Products Insider webinar on probiotics regulations and class-action lawsuits.

How Does the FDA Define Probiotics?

It wasn’t until 1994 that probiotics were allowed to be sold as an FDA-approved dietary supplement. But the Dietary Supplement and Health Education Act (DSHEA) of 1994 does not directly define probiotics in their definition of supplements.

“You’ll notice there’s nothing in there about live microorganisms,” Wasserman says.

A line interpreted as a “catch-all” provision covers probiotics. It says a dietary substance can be anything “to supplement the diet by increasing the total dietary intake.” The FDA reviewed DSHEA in 2019, but new draft guidelines don’t provide additional clarification. The draft states: “Bacteria that have never been consumed as food are unlikely to be dietary ingredients.”

Wasserman says that’s not a correct assessment of probiotics. During the review, he noted government leaders who were around during DSHEA’s first passing said dietary supplement should not “be limited to things that are already in the food supply. That would really kill innovation, new strains of probiotics for example that were never in the food supply. It didn’t make sense to them that that would be the intent of congress. It would stifle innovation.”

As the FDA’s time is overwhelming focused on coronavirus, there has been no resolution to the definition of probiotics.

What are the Challenges in Labeling Probiotics?

Current regulations call for labeling probiotics in terms of weight. There is no special provision for live microorganisms; probiotics must be labelled like a vitamin or mineral.

“Unlike milligrams of calcium or vitamin C, we all know weight really isn’t that relevant (for probiotics) because dead bugs have weight, the size of the bug really doesn’t affect its efficacy,” Wasserman says. “It’s really how many live microorganisms you’re getting taking as part of a dietary supplement. That’s how all research is published, that’s how the government refers to it. So CFUs, or colony forming units, has become sort of a defacto way consumers and companies will recognize how much of a live microorganism a probiotic is in a live, dietary supplement.”

The International Probiotics Association petitioned the FDA on this measurement rule, asking for probiotics to be listed in terms of CFUs, not milligrams. The FDA said yes, CFUs would be allowed, but milligrams must also be included.

“It’s just confusing and silly,” Wasserman says.

False Advertising Claims Can Cost Brands Millions

In the past decade, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) has actively sent warnings to brands making unverified probiotic health claims. The FTC’s first charge for probiotic advertising was filed in 2010 against Nestle BOOST Kid Essentials. Nestle did not have the scientific evidence to back up their health labelling. The FTC said Nestle used “deceptive advertising claims about the health benefits of the children’s drink,” like claiming it would reduce the risk of colds, flu and other respiratory tract infections, claims unproven by the FDA. Nestle also claimed BOOST would reduce children’s sick-day absences and decrease the duration of diarrhea, claims unverified “by at least two well-designed human clinical studies,” the FTC said.

“You have to be extremely careful not to imply or state disease prevention,” Wasserman says. “Probiotics certainly give a boost to the immune system, but…to the FTC, that was too strong of a claim, that this product can literally prevent children from getting sick. You can get in trouble for both imagery and claims. Be very careful.”

Other deceptive advertising cases include:

- In 2010, the largest truth in advertising lawsuit was settled against Dannon yogurt. Dannon claimed their Activia and DanActive yogurt products were “clinically” and “scientifically proven” to regulate digestion and boost the immune system. However, Dannon never proved their claims. Dannon had to pay $45 million in damages, and remove the words “clinically” and “scientifically proven” from their labels.

- In 2018, a class-action lawsuit was filed against Tropicana for marketing the added health benefits in their Essentials Probiotics fruit juices. The drink, though, included nearly the same amount of sugar as soda, and Tropicana did not have adequate scientific evident to support the nutritional claims.

- In 2019, a lawsuit was filed against Brew Dr Kombucha, alleging the kombucha was “falsely advertised and labeled as having a significantly higher amount of probiotic bacteria than the products sold actually contained.” Brew Dr’s kombucha bottle advertised billions of bacteria per bottle, but the plaintiff’s research found only 50,000 CFU’s of probiotic bacteria per bottle. The case is still pending.

- In May 2020, the National Advertising Division (NAD) recommended Benefiber remove the claims “100% natural,” “clinically proven to curb cravings” and “helps you feel full longer” from the Benefiber fiber supplements. Metamucil challenged Benefiber’s claims. Though Benefiber had tested their products and could provide scientific evidence, the NAD said the studies were not relevant to the consumer population. Benefiber’s studies were conducted on factory workers in China who live in a controlled living environment at the warehouse 24/7.

In the last few years, the FTC has been relatively quiet filing warnings against probiotic products. Wasserman theorizes it’s because the benefits of probiotics to digestive health have become well-accepted to the general public. Class-action lawsuits filed against probiotic products have also slowed down.

“That’s not to say they’re not being filed,” Wasserman adds. “We’re not seeing a letdown of those types of letters. Our little law firm is dealing with them on a daily basis for a wide variety of clients in a wide variety of industries. The good news is, because the benefits are so well known of probiotics, we haven’t seen a lot of cases actually being filed against probiotics.”

- Published in Science