The Flavor Whisperer on Fermentation

Flavor is much more complex than just taste. Flavor can be collected, extracted, infused, created and transformed. And, in a billion-dollar flavor industry devoted to putting flavors into processed foods, fermentation is the oldest and most natural flavor creator, developing new flavors at a molecular level.

“Fermentation as a flavor creation process in collaboration with microbes, there’s almost no limit to how you can apply it and use the ingredients around you and have a more flavorful palette to work from,” says Arielle Johnson, PhD, a flavor scientist, gastronomy and innovation researcher and co-founder of the Noma Fermentation Lab.

A food chemist dubbed the flavor whisperer, she works with restaurants on innovating dishes and cocktails. She researches how flavor is perceived and is writing a book on her studies, Flavorama. Her work comes together in “all things science and cuisine have to say to each other.”

This week Johnson shared her insights into flavor and fermentation as a guest lecturer at Harvard University’s Science & Cooking series.

Taste & Smell Receptors

Flavor can be quite complex – Johnson calls it a black box.

There are five primary tastes: sweet, sour, salty, umami and bitter. Each taste evolved to ensure humans get basic nutrition. We use sweet foods for the energy in sugar, sour ones for vitamin C from fruit and fermented foods. Salty foods provide the essential mineral sodium. We seek umami foods for the taste of glutamine, an amino acid in proteins and fermented foods.

But bitter, Johnson points out, doesn’t sense one thing. It senses multiple molecules that are potential toxins for us. This is why bitter is called an acquired taste.

Smell is Johnson’s favorite part of the flavor profile. In order to taste, we must smell, too. Molecules land in the olfactory receptors in the nasal cavity and help activate taste. This is why food is tasteless if you plug your nose while eating. But the back of the throat is also connected to the nasal cavity, so the throat becomes “the secret backdoor” for sensing flavor.

While there are five major tastes and four receptor areas on the tongue, there are 40 billion smellable molecules and 400 receptors for smell.

Supertasters vs. Nontasters

Taste and smell, she detailed, help us understand how fermentation works.

The population can be divided into supertasters or nontasters. During her presentation, Johnson had the audience put a strip of filter paper on their tongue. The paper included a harmless bitter molecule phenylthiourea (PTC), but only roughly half the class could taste it. This group are supertasters – the group who could not taste the PTC are nontasters.

She explained everyone has different density of their taste buds. Supertasters have more taste buds, so more taste receptors signals are sent to their brains. This has culinary implications. Because their sense of taste is more sensitive, flavors are intense and supertasters have a less adventurous palette. Meanwhile nontasters have dulled senses, so it takes a lot of flavor to activate taste.

“The good news for supertasters is that fermentation is usually salty and sour and often umami – all of which counteract bitterness,” Johnson says. “Fermentation is a way to create new flavors but also transform ingredients.”

Fermentation as Flavor

Though “microbes are opportunistic” and pop up in foods whether planned or not, fermentation can’t be forced, Johnson says. When making a sauerkraut, for example, microbes don’t need to be added. Fermentation works with what’s on the surface of the cabbage and on the producer’s hands.

Salt is key in fermentation as a flavor additive, a preservation element and a safety measure. Salt filters out bad molds and avoids letting a ferment spoil. Other factors “dial in the flavors in this molecular flavor creation process,” she says, like the correct ingredients, temperature control and humidity.

“We’re really excited about microbes and fermentation,” Johnson says. “In this process of this exponential growth that microbes do, they’re eating things, they’re getting energy, but they’re also running their regulator metabolism. So there’s all these waste products that are not very significant to the microbes, but that can create a lot of interesting flavor complexity.”

- Published in Food & Flavor, Science

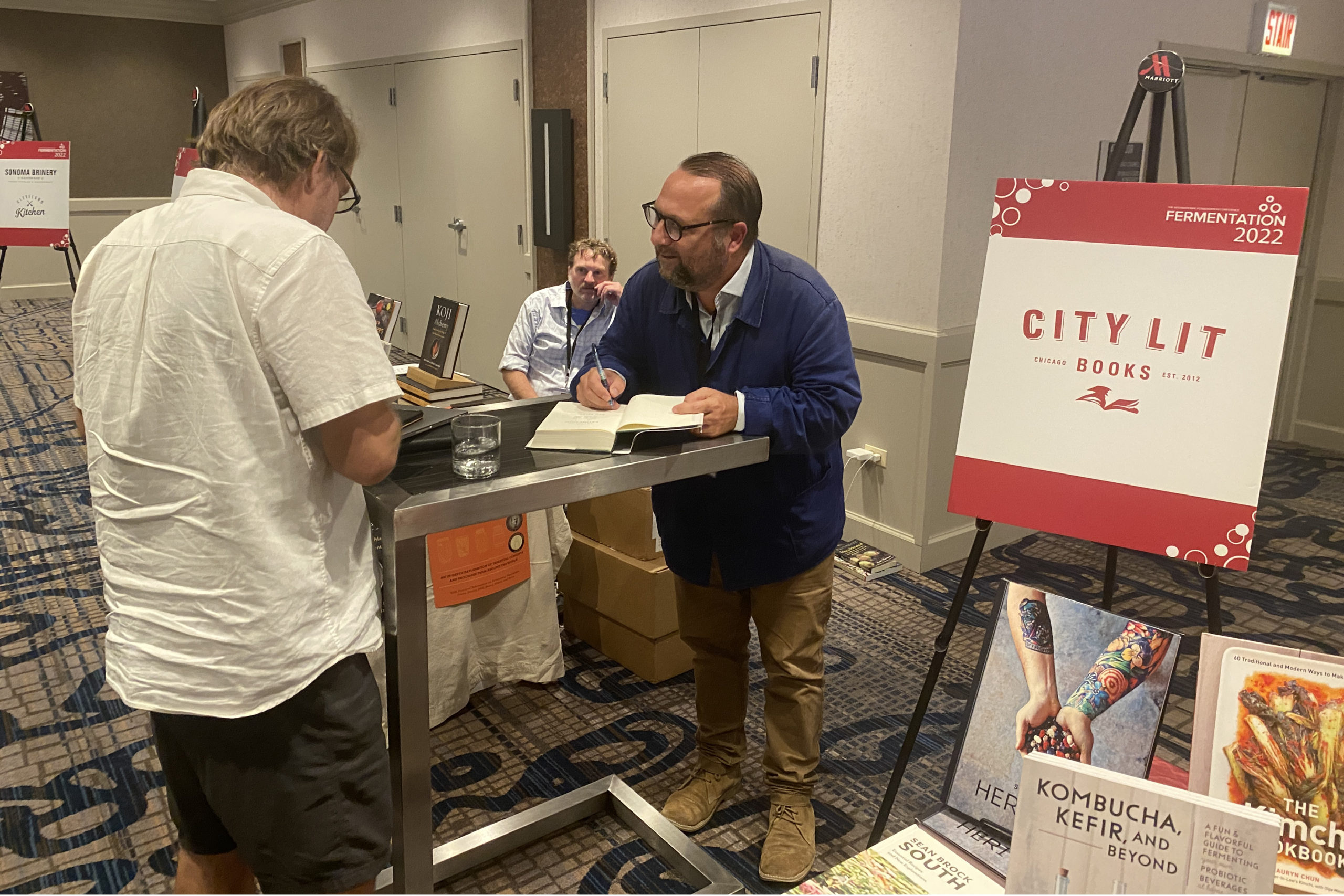

Cultured in Chicago: Highlights of FERMENTATION 2022

Science met the culinary arts in Chicago, at the first in-person conference of The Fermentation Association (TFA), FERMENTATION 2022. Over 200 food and beverage professionals from 15 countries Participated in four days of programming.

“There’s no denying that fermentation is having a moment – and that’s a wonderful thing that more and more people are aware of fermentation and interested in fermentation – but it’s really important to keep saying fermentation is not a fad, fermentation is a fact,” said Sandor Katz, fermentation author and educator.

Katz was the opening keynote speaker at FERMENTATION 2022. The nearly 50 experts and thought leaders who presented included Dan Saladino (BBC journalist and author of Eating to Extinction), Kirsten Shockey (author, educator and co-founder of The Fermentation School), Bob Hutkins (food microbiology professor at University of Nebraska and founder of Synbiotic Health), Sharon Flynn (founder of The Fermentary in Melbourne, Australia), Bruce Friedrich (co-founder and executive director of The Good Food Institute), Maria Marco (food science professor at University of California, Davis) and Sean Brock (chef and owner of Nashville’s Audrey Restaurant).

The conference comes as sales of fermented foods and beverages continue to rise. Fermented products grew 7.1% in the last year, according to SPINS LLC, a data provider for natural, organic and specialty products that also presented at FERMENTATION 2022.

Though Katz taught his first fermentation workshop in 1998, he’s seen “a building interest in fermentation” in the last decade. Each year since 2011, “someone says the food trend of the year is fermentation.”

“Usually I end up being a cheerleader for fermentation, encouraging people who somehow think that fermentation is an alien process, that there’s something scary about it,” he said. “I mostly reassure people that they’ve been eating products of fermentation almost every day for their entire lives, that these are processes that their safety has been proven by their endurance over time. But you all don’t need to hear that. I am speaking to the converted here.”

Where Science Meets Industry

TFA aims to fill a niche in the world of fermentation. There are plenty of DIY fermentation festivals, food and beverage industry conferences and trade shows. But TFA connects science and industry.

Attendees at the event included an array of professionals involved in fermentation – producers, retailers, chefs, scientists, researchers, authors, suppliers, educators and regulators. The conference revolved around three tracks: food, flavor and culture; science and health; and business, legal and regulatory. The group of passionate fermenters in attendance uniformly expressed their excitement and delight to learn from experts in different disciplines.

“This unique conference had the most diverse attendees as it included chefs, scientists and more,” said Glory Bui, a graduate student researcher at the University of California, Davis. “It was nice to network with those who were and were not in academia to hear different perspectives in the fermentation industry.” [Bui won the student poster competition with her research on how fermented dairy products can affect gastrointestinal health.]

Producers made up over 40% of attendees and ran the gamut from small to large scale. Sash Sunday, founder and fermentationist behind OlyKraut in Olympia, Wash., said she’s been searching for such a fermentation conference since starting her brand in 2008.

“I really appreciate getting to spend time getting to know other fermenters, hearing about people’s creative processes and experiences in the field,” Sunday said. “I really loved all the tastings and spending time with people who really think about the flavors in fermented foods.”

Niccolo Fraschetti, owner of Alive Ferments, said networking was one of his favorite parts of the conference.

“There were people there that were superstars of fermentation to people making kimchi in the bathtub,” Fraschetti said. “It was such a cool merging of fermentation.”

Fraschetti officially launched Alive Ferments in March and said he never expected the brand to grow so fast, so quickly. Alive Ferments currently is sold in 25 stores in the San Diego area. At FERMENTATION 2022, he brainstormed ideas with attendees and speakers.

“Usually I feel like in these situations, everyone is tight-lipped and doesn’t want to share (business secrets),” he said. “But everyone was a really embracing community and willing to share their knowledge. There was no competition between the peers that were at the conference.”

Connecting with others in the industry was a highlight, too, for Suzette Smith, founder of Garden Goddess Ferments and Pick up the Beet in Arizona.

“I loved that like minds were able to come together sharing similar passions,” Smith said. (I also loved “learning what’s new in the promotion of fermented foods.”

Gregory Smith, an independent chef based in Pittsburgh, said he “drove back from Chicago with my mind racing about all the things I learned.” He said the various chefs who spoke at the conference – like Flynn, Brock, Ismail Samad of Wake Robin Foods, Jessica Alonzo of Native Ferments, Misti Norris of Petra and the Beast and Jeremy Kean of Brassica Kitchen – inspired him to dive into upcycling.

“I’m excited about the way they made me look at food waste in the kitchen space and how to help utilize waste and taking excess product and converting it into something tasty,” said Smith, who runs his independent culinary service Thyme, Love & Culture with friend Romeo Kihumbu.

Karen Wang Diggs, founder of the ChouAmi fermentation device, spoke at the event in a session on fermenting with medicinal plants. She said it was “an honor” to speak at FERMENTATION 2022.

“I got to hang out with a bunch of really cool, ‘cultured,’ fermenting people – and the presentations were fabulous,” she said.

Added Neal Vitale, executive director of The Fermentation Association: “It was a privilege to have a stellar lineup of speakers. It was great to get to get together at last and explore so many aspects of fermentation.”

Focus on Food

Other events at the conference included: a dinner with a fermentation-focused menu prepared by Rick Bayless, chef and restaurateur; a mezcal tasting with Lou Bank, founder of SACRED and the Agave Road Trip podcast; a craft beer and chocolate pairing with Long Beach Beer, Bread and Spirits Lab; a flavor analysis workshop with Sensory Spectrum Inc.; a screening of Ed Lee’s film Fermented (complete with buttered popcorn!); and multiple book signings.

Bayless, the James Beard Award winner who runs multiple Chicago restaurants, mingled with conference attendees during the dinner. He said he and his staff enjoyed the challenge of putting something fermented in every course.

“This is the first time we’ve done a meal that is so heavily fermented,” he said, “and we had a lot of fun doing it.”

Courses included a fermented corn masa tamal, beed with a fermented black bean sauce made with black bean miso and Oaxacan pasilla chile, smoked yellowfin tuna in a broth of tejuino (fermented corn drink), and chocolate from Tabasco, Mexico, with tepache (fermented pineapple) sorbet .

“I was at a conference with Sandor Katz years ago and I talked to him about making black bean miso, and now I get to serve it to him,” Bayless said.

The Fermentation Association was started in 2017 as the brainchild ofJohn Gray, then the owner of Bubbies Pickles. His goal was simple – to bring together everyone in the world of fermentation. Today, TFA circulates its biweekly newsletter to nearly 14,000, is followed by over 11,000 on Instagram and will next develop its presence on LinkedIn. The Association is run by a small staff and a 22-member Advisory Board, including six Science Advisors.

FERMENTATION 2022 was originally planned to be a May 2020 event, but obviously postponed due to Covid-19. A virtual FERMENTATION 2021 was held in November 2021. TFA will announce plans for 2023 and beyond in the coming months.

- Published in Business, Food & Flavor, Health, Science

Endangered Fermented Foods

Through selective breeding and domestication of plants and livestock, the world’s food system has lost diversity to an alarming degree. Crops are monocultures and animals are single species. Journalist and author Dan Saladino argues it’s vital to the health of humanity and our planet to save these traditional foods.

“There’s an incredible amount of homogenization taking place in the last century, which has resulted in a huge amount of concentration of power in the food system but also a decline in the amount of biodiversity,” says Saladino, author of Eating to Extinction. “That agricultural and biological diversity is disappearing and it’s taken us thousands, millions of years for plant, animal evolution to get to this point.”

Saladino was a keynote speaker at The Fermentation Association’s conference FERMENTATION 2022, his first in-person talk in the United States since his book was released in February. A journalist with the BBC, Saladino was also an active participant in the event, attending multiple days’ worth of educational sessions. He called the conference “mind expanding.”

“I thought I knew about fermentation, when in fact I know very little,” Saladino said to the crowd in his keynote. “We’ve been bemused by the media reports that fermentation is a fad or fashion. What we know is that the modern food system in the last 150 years is the fad. It’s barely a blip in the context of our evolution as species, and it’s the way we’ve survived as a species over thousands of years.”

Eating to Extinction includes 40 stories of endangered foods and beverages, just touching on a fraction of what is happening around the world. To date, over 5,000 endangered items from 130 different countries have been cataloged by the Slow Food Foundation’s project the Ark of Taste.

During FERMENTATION 2022, Saladino centered his remarks around the endangered fermented foods he chronicled in his book – Salers cheese, skerpikjøt, oca, O-Higu soybeans, lambic beer, pu’erh tea, qvevri wine, perry and wild forest coffee. Here are some of the highlights of his presentation.

Salers cheese (Augergne, Central France)

Fermentation was a survival strategy for many early humans, a fact especially evident in the origins of cheesemaking. In areas like Salers in central France, villagers live in inhospitable mountain areas where it’s difficult to access food. In the spring each year, cheesemakers travel up the mountains with their cattle and live like nomads for months.

“It’s extremely laborious, hard work,” Saladino says, noting there’s only a handful of Salers cheese producers left in France. He marvels at “the ingenuity of taking animals up and out to pasture in places where the energy from the sun and from the soil is creating pastures with grasses with wildflowers and herbs and so on.”

Unlike with modern cheese, no starter cultures are used to make Salers cheese. The microbial activity is provided by the environment – the pasture, the animals and even the leftover lactic acid bacteria in the milk barrels. Because of diversity, the taste is rarely consistent, ranging season to season from mild to aggressive.

“The idea of cheesemaking is a way humans expand and explore these new territories assisted by the crucial characters in this: the microbes,” he adds. “It can be argued that cheese is one of most beautiful ways to capture the landscape of food – the microbial activity in grasses, the interaction of breeds of animals that are adapted to the landscape. It’s creating something unique to that place.”

Skerpikjøt (Faroe Islands)

Skerpikjøt “is a powerful illustration to our relationship with animals, with meat eating,” Saladino says. It is fermented mutton and unique to Denmark’s Faroe Islands. Today’s farmers selectively breed their sheep for ideal wool production, then slaughter the lambs for meat. In the Faroes, “the idea of eating lamb was a relatively new concept.” Sheep are considered vital to the farm as long as they’re still producing wool and milk.

Once a sheep dies or is killed, the mutton carcass is air-dried and fermented in a shed for 9-18 months. The resulting product is “said to be anything between Parmesan and death. It certainly has got a challenging, funky fragrance,” Saldino says.

But it contrasts traditional and modern food practices. Skerpikjøt is meant to be consumed in small quantities, delicate slivers of animal proteins used as a garnish. Contemporary meat is served in large portions and meant to be consumed quickly.

Oca (Andes, Bolivia),

In the Andes – “one of the highest, coldest and toughest places on Earth to live” – humans have relied on wild plants like oca, a tuber. After oca is harvested, it’s taken to the Pelechuco River. Holes are dug on the riverbank, then filled with water, hay and muna (Andean mint). Sacks of oca are placed in the holes, weighted down by stones, and left to ferment for a month. This process is vital as it leaches out acid.

“Through processing, this becomes an amazing food,” Saladino says.

But cities are demanding certain types of potatoes, encouraging remote villagers to plant monocultures of potatoes which are prone to diseases. The farmers end up in debt, buying fertilizers and pesticides to grow potatoes.

“For thousands of years, oca and this fermentation technique and the process to make these hockey pucks of carbohydrates and energy kept them alive in that area,” Saladino says. “It’s a diversity that is fast disappearing from the Andes.”

O-Higu soybeans (Okinawa, Japan)

The modern food industry is threatening the O-Higu soybean, too. It was an ideal soybean species – fast-growing, so it can be harvested before the rainy season and the arrival of insects.

“But by the 20th century, the soy culture pretty much disappeared,” Saladino says.

With World War II came one of America’s biggest military bases to Japan. U.S. leaders dictated what food could be planted on the island. Okinawa was self-sufficient in local soy until American soy was introduced.

Lambic Beer (Belgium)

Saldino explained that, after a spring/summer harvest, Belgian farmers became brewers. They used their leftover wheat to create brews unique to the region.

But by the 1950s and 1960s, larger brewers began buying up the smaller ones. Anheuser-Busch InBev now produces one in four beers drunk around the world.

“There [is] story after story of these distinctive, unique, small breweries disappearing as they are bought up or absorbed into this growing, expanding empire of brewing,” Saladino says. “It’s probably one of the most striking cases of corporate consolidation of a drink and food product.”

Saladino stressed not all is lost. He shared stories of scientists, researchers and local people trying to save endangered foods, collecting seeds, restoring crops and combining traditional and modern-day practices to preserve the world’s rare foods.

“There have been so many fascinating stories of science and research discussed over the last few days at this conference, and I think the existence of The Fermentation Association is exciting because it is bringing together tradition, culture, science, culinary skills, all of these things we know food is,” Saladino added. “Food is economics, politics, geography, anthropology, nutrition. What I’m arguing is that these clues or glimpses into the past for these endangered foods, they’re not just some kind of a food museum or an online catalog. They are the solutions that can help us resolve some of the biggest food challenges we have.”

- Published in Food & Flavor

Why did Americans Turn to Drinking ACV?

A deep dive on Epicurious explores how apple cider vinegar (ACV) became America’s favorite. It is popular today as a detox tonic, but has a deep history in the U.S., “intertwined with the global spread of apples and with the transformations of fermentation.”

Today, vinegar is considered an industrialized condiment but, until the 19th Century, it was homemade. Kirsten Shockey, author of Homebrewed Vinegar (and a TFA Advisory Board member) notes the key to making vinegar is nurturing the natural fermentation process. “Vinegar happens whether you want it to or not,” she says. “As soon as fruit is picked, it’s a race against time,” she adds. As the fruit ripens, wild yeasts ferment their sugars into alcohol. Microbes feast on that alcohol, converting it to acetic acid.

Paul C. Bragg, namesake of the Bragg vinegar brand, helped popularize commercial vinegar. Theirs is still a raw, unpasteurized ACV. Paul preached the benefits of vinegar as far back as in the 1970s. This support coincided with “the rise of a countercultural natural food movement, which embraced the brown, gritty and ‘all-natural’ in its refusal of the refined, bleached and heavily processed products of the industrial food system.” (Pop star Katy Perry invested in Bragg in 2019).

The article also highlights artisanal vinegar brands, like American Vinegar Works in Massachusetts and two Pennsylvania producers, Supreme and Keepwell.

Isaiah Billington cofounder of Keepwell says that making vinegar “helps us interact closely with the total landscape of local agriculture.” Vinegar also uses produce that can’t be sold because it’s too ripe, or because the apple is “very ugly.” “We work at the margins of the harvest.”

Read more (Epicurious)

- Published in Food & Flavor

Brewing Boom in Chicago

Dubbed the craft beer capital of America, Chicago has a brewery scene that is innovative and diverse. Numerous breweries have opened over the last decade, with now about 160 breweries across the city and surrounding suburbs. Ferment Magazine says Chicago’s craft brew industry is “one of the most expressive and most exciting experiences anywhere in the world, let alone in the U.S.”

“We have a very strong culinary scene in Chicago and a lot of consumers that have an open mind. There’s a lot we could throw at the market and people are very accepting of the different brewing styles, both old world and new world,” says Tyler Davis, founder and director of fermentation at Duneyrr Artisan Fermenta Project. “Of all the [different beer styles] we could produce, there are brewers in Chicagoland that specialize in that.”

Chicago’s Brewers

Duneyrr (pictured) focuses on co-fermentation. Using craft beer as a base, Davis makes fermented drinks with ingredients from wine, cider and mead.

“It all came from me reaching the end of my creativity in a brewery. I got tired of creating the same format,” says Davis, who worked in Chicago as head brewer at Lagunitas and at Revolution Brewing. He began experimenting with co-fermentation and found “how you ferment wine is shockingly similar to beer. There are nuances of both, but I enjoy blurring the lines.”

The Nordic-inspired drinks he produces include his favorite, Freya Franc,(a sour hybrid with passion fruit and Sauvignon Blanc grape must. Duneyrr also has a Moderne Dune line, a sister brand that specializes in modern ingredients and techniques.

Davis studied at the Chicago-based Siebel Institute of Technology, the oldest brewing school in the U.S. and alma mater to many area brewers. One alum is Dave Bleitner, who founded Off Color Brewing with his Siebel classmate, John Laffler. The two focus on funky fermentation.

“Even with our first flagship gose, Troublesome, we have always been fermentation-focused. Even when we are dumping in a bunch of rooibos tea and pumpkin pie spices into a beer, we believe beer needs a proper fermentation to work,” Bleitner says. “Maximizing flavor from yeast is always going to result in a superior beer. But beyond our focus on fermentation, we are not afraid to dump a bunch of rooibos tea and pumpkin pie spices into a beer. So the dual concepts of focusing on the basics of fermentation while teetering on the border of innovative and insane is something no one else should or can replicate.”

When Off Color launched in 2013, Bleitner and Laffler didn’t want to go the mainstream craft beer route. “We had some crazy idea that craft beer consumers wanted variety from their beer,” Bleitner said. They didn’t follow the usual craft beer formula of launching with an IPA. They started with lesser-known styles like gose and kottbusser. He notes “we really hit our stride with Apex Predator Farmhouse Ale.”

At 15 years old, Half Acre Beer is one of Chicago’s pioneers of the craft beer scene. The brewery is the third-largest independent brewer in Illinois and now distributes their beer all over the country. They run a brewery and taproom in Chicago. Their best seller is Daisy Cutter pale ale, but they also sell seasonal and monthly varieties.

“These days we’re kind of the older, bigger brewery among the smaller, newer breweries. We focus on hop-forward and traditional beers,” said Gabriel Magliaro, president of Half Acre. He echoed the sentiment expressed by Duneyyr and Off Color – Chicago brewers are a supportive community. “Today I think we can call Chicago a beer town and, no matter how you choose to define that, we show up well.”

The Next Beer Buzz

Craft beer brewers see increasing competition from the better-for-you, healthier fermented drinks, like kombucha, seltzer and low- or non-alcoholic beverages.

Duneyrr is starting to specialize in lower-alcohol fermented brews. Off Color, too, has added a lower-alcohol beer, a 2.5% ABV Belgian-style they call Beer for Lightweights.

Lagers are making a comeback as well. “A lot of old world brewing styles, there’s become a renaissance,” Davis says. He sees “candy beers” – filled with artificial flavors – going away. Bleitner, too, is not a fan – he calls hard seltzers “fermented pixie sticks”. But he’s found that consumers like flavor in their brews. When sales of Off Color’s Troublesome gose began to decline, adding lime juice revived the drink. They called it Beer for Tacos and “it took off almost immediately.”

In an era fraught with pandemic shutdowns, retail inflation and supply chain issues, brewers foresee challenges ahead.

“Obviously the pandemic has been a factor, one that is still playing out,” Magliaro says. “The on-premise was rocked and I don’t think anyone knows how that will look in five years.”

Climate change is affecting grain crops, “things we knew to be stable are now being highly influenced by the weather patterns,” Davis says. The hot weather is changing the nutrient level of grains, leading to grains higher in protein. “It’s pretty scary,” he says.

But beer will always find a way to thrive.

“We make something embedded in human culture,” Magliaro says. “Beer is a gathering liquid that has place almost anywhere for almost any occasion with so much heritage to its being. The industry, consumer landscape and world can do what it needs, but beer will live on.”

- Published in Business, Food & Flavor

The State of Fermentation Education

The Covid-19 lockdown spurred aspiring home chefs around the world to try fermenting for the first time. DIY classes moved virtual and countertops filled with bubbling crocks of kimchi, sauerkraut, kombucha and sourdough. Fermentation was one of the top pandemic hobbies.

For professional fermentation educators, this trend brought new, eager faces to classes. But now, as lockdown restrictions have eased, are people still wanting to experiment making their own microbe-rich food?

We asked three experts to share their thoughts on the current state of fermentation education — author and educator Kirsten Shockey (of The Fermentation School and Ferment Works), writer and educator Soirée-Leone (who can be found via her website) and chef, food scientist and fermentation educator Jori Jayne Emde (of Lady Jayne’s Alchemy and The Fermentation School). [Shockey and Soirée-Leone are both members of TFA’s Advisory Board.]

The question: What is the current state of fermentation education?

Kirsten Shockey, author and educator

Fermentation education is exploding. The time has never been better. The interest in fermentation — both as a topic and in hands-on engagement — keeps gaining momentum. People are both more curious and more confused than I have seen in the past. I think part of that is because with the boom of interest a lot of people are coming forward as experts sharing content without the prerequisites to inform accurately. For example, we see misinformation about the subtle differences in fermentation vs. culturing vs. pickling that end up leaving people who are just dipping their toes in the process a little less unsure. When these folx do engage with true experts they are enthusiastic students who enjoy soaking up all that they can and we see their anxieties dissipate. I speak from the experience of working with solid experts and their students through The Fermentation School. It has been beyond gratifying to work with an amazing group of really talented fermentation educators to grow quality online education and a dedicated “help” community through The Fermentation School. In my other educator hat, as an author, it is less clear to me how that media is working for education, but that is a bigger issue in that the publishing world itself is in a lot of flux.

Soirée-Leone, writer and educator

Folks are connecting with familial, cultural, and traditional roots through fermentation. They are building online communities to share knowledge, taking workshops, participating in residencies, checking books out from libraries, and attending fermentation festivals that are popping up all over the world.

While there is an abundance of information available through books and websites, some folks seek to connect in person through workshops. I find that it’s especially dynamic to teach and learn in collaborative environments to share skills and experiences. There are so many traditions, techniques, and riffs. It is exciting to learn about folks’ travels, study, and experiments — we each have a different fermentation journey and something to teach and learn.

Today is a far cry from when I first started cheesemaking in 1991 with one slim book that sang the praises of junket rennet. Now there are books sharing natural cheesemaking techniques, bloggers happy to answer questions, travelers bringing information home and sharing online, and workshops to attend.

Fermentation is accessible with rudimentary kitchen equipment and improvised incubators and cheese caves. Fermentation is empowering and engaging of all our senses—and learning new things about fermentation is a never-ending journey.

Jori Jayne Emde, chef, food scientist, fermentation educator

My perspective on this is it’s booming! There was a huge burst of interest for online learning during the pandemic, and I have not seen that slow down much. Fermentation is a trendy topic and word with, unfortunately, a tremendous amount of misinformation floating around out there. It’s an important time as an educator to really remain engaged with students, as well as capturing fermentation aspirants, guiding them towards proper and well informed education taught by experts in the field of fermentation and health.

- Published in Food & Flavor

Zilber: Fermentation’s Endless Potential

David Zilber says the potential for fermented food is endless. “There isn’t any sort of food that doesn’t benefit from some aspect of fermentation,” he said. “There’s really no limitation to its application.”

Zilber, the former head of the Noma fermentation lab, co-authored “The Noma Guide to Fermentation” with Noma founder Rene Redzepi. In the fall of 2020, Zilber surprised the food world when he left his job at Noma to join Chr. Hansen, a global supplier of bioscience ingredients.

He shared his insight on fermentation on The Food Institute Podcast. An Oxford study found over 30% of the world’s food has been touched by microbes. Zilber, a microbe champion, says one of the best parts of fermenting with plant-based ingredients is the microbes don’t need to change.

“We do need to find ways to adapt them to new sources, but there will always be a place within the pie chart of what humans are eating on earth for fermentation,” he says.

Part of Zilber’s work at Chr. Hansen is in the plant-based protein alternative segment, fermenting plant ingredients to “bring this other set of characteristics” to a new food item. He advises fermenters using plant-based ingredients to make their ingredient list concise and pronounceable to consumers.

“I am a huge proponent for formulating recipes from whole ingredients,” Zilber says. “Keeping the ingredient list short and concise and using natural processes to achieve flavor or textual properties … because it is the healthiest way to eat.”

Across the spectrum of fermentation, he feels fermented beverages is the category where he sees the greatest opportunity.

Read more (The Food Institute)

- Published in Food & Flavor

Redzepi on the Changing Fine Dining Industry

Expect more changes to fine dining as the restaurant industry grapples with Covid-19 changes, casual eateries adapt more fine dining techniques and the war in Ukraine continues to affect the world economy.

“Everyday restaurants have become so amazing. It’s not like it used to be, you used to go to the best restaurant to get the most tender piece of meat and the perfect ice cream,” says Rene Redzepi. He is the founder of Noma, the Michelin three-star restaurant in Copenhagen lauded as one of the top in the world. “You can find typical luxury ingredients like caviar and wagyu in airports. The quality of cooking now is so high.”

Redzepi spoke at Madrid Fusión, one of the largest and oldest international gastronomy conventions. Andoni Luis Aduriz, chef and owner of the renowned Spanish restaurant Mugaritz, spoke with Redzepi.

Redzepi says there’s been a “flavor spread” or “quality spread” of gastronomy techniques. He points to espumas, the Spanish term for culinary foaming. – now used on every continent, in every level of restaurant. A gourmet dish may come from the neighborhood brasserie, a tapas bar or even a food truck. It’s “dramatically changed” the restaurant industry, he notes.

“That’s because people don’t understand the influence and the philosophies that [are] now completely naturalized in every corner of gastronomy,” he says. Techniques once used only in premier establishments have become part of cooking DNA. “I hope fermentation will be that because I genuinely believe in the power of that.”

When Noma opened in November 2003, Redzepi promised Nordic cuisine made with local produce. But it was winter and freezing, making sourcing food a challenge, “so I stepped into the wilderness to find flavors.”

He also realized Noma needed to conserve summer produce for the long winter.

“We started to use pickling, fermentation, drying, smoking. Twenty years later, we have this bank of knowledge,” he said. “Before, we used to try 20,000 different fermentation techniques, now we are trying one at a time, with the whole team, like we are doing with lacto-fermentation.”

Fermentation drives an enormous amount of innovation at Noma. Redzepi told the Madrid Fusion audience that the restaurant industry is one of the most difficult to work in, so innovation and experience are what drive profitability.

“That’s what makes it special, putting together a team, while constantly looking for the ‘next big thing,’” he says. “That’s where the challenge is; pushing yourself outside of your comfort zone, until you have no clue what you’re doing, but as a group, you draw on your experiences, you trust each other, and you dare to move onwards.”

Redzepi praised the current state of Spain’s cuisine, saying “the Spanish influence is a natural part of any fine dining kitchen in the Western world.”When he was starting out in the 90s, French food was the only focus for chefs. “You were going to cook French food in Denmark, that’s what I always thought to myself.” But when he took a job cooking in Spain for a season, “it was like everything that you had been taught before, all your rules that you knew, were sort of thrown away and you could build and dream in a different way. “[Spanish cuisine] has given me the very seed of everything that’s become Noma.”

- Published in Food & Flavor

Color of Food Culture

The United States is becoming more diverse, with 4 of every 10 Americans identifying as non-white. But grocery stores have been a poor reflection of that mix of cultures. Now, a group of BIPOC food entrepreneurs are encouraging buyers and retailers to expand the range of products featured on store shelves.

“It has to start with leadership at the top saying, ‘We have to champion emerging brands because it’s good business,’” says Clara Paye, founder of UNiTE Foods, a maker of protein bars with international flavors. “Let’s face it. Your customers are diverse. They’re looking for diverse products. Create the incentive structures for buyers out there to have those placements and do it confidently.”

Paye was part of a panel at Natural Products Expo West discussing the challenges and opportunities for founders of color. The U.S. food system, the panelists lamented, is far from equitable. For example, though foods like kimchi and miso are staples in Asian countries, shoppers are hard-pressed to find a broad and deep array of multicultural food products at a typical American grocery.

“There wasn’t an avenue if you weren’t born and raised in America,” Paye explains.

Reclaiming Food Culture

The panel stressed that they could never find the traditional foods they ate growing up when they went to American grocery stores. First- and second-generation immigrants have never been the focus of major retail food brands. Underserved in this way, these BIPOC founders say they started their companies to reconnect with the flavors of their cultures.

“We felt it was a travesty that the second largest continent in the world [Africa] didn’t have any reflection in mainstream grocery,” says Perteet Spencer, founder of Ayo Foods, which sells West African frozen dishes and jarred sauces. (Spencer — a former employee of SPINS, a retail sales data provider for natural products — spoke at a TFA webinar in 2021).

But she notes the food system is changing: “It’s clear that the market has shifted over the last several years and is embracing global flavors.”

Expanding the flavor of Mexican cuisine is the goal of Miguel Leal, co-founder and CEO of Somos, maker of Mexican meal kits.

“There’s stereotypically this (belief) that ethnic food has to be cheap,” he says. “It can be beautiful or clean or premium.”

Vanessa Pham agrees, adding there’s a narrative that authentic ethnic food should only be served in hole-in-the-wall restaurants. Pham is co-founder of Omsom, which makes chef-created Asian dishes. “Authentic” is a complicated term, she says.

“Authenticity sometimes pegs and limits food founders and chefs to a nostalgic idea, ‘How my grandma made it’ or ‘The traditional way,’” she explains. “We believe BIPOC chefs should be able to innovate. Cultural integrity is much more about doing your research, involving the right people and compensating ethically.”

Ethnic Aisle: Integrate or Celebrate?

The ethnic aisle in groceries is a debated topic among BIPOC food leaders. Some say it’s an easy way for shoppers to find international products; others argue it’s an antiquated and offensive placement.

“I like the ethnic aisle, I just don’t like the way it’s showing us today,” Leal says. “It’s a little bit of a caricature.”

A recent survey by Adobe found 66% of African Americans and 53% of Latinos feel their ethnicity is portrayed stereotypically in food advertisements.

Pham views a future where the hodgepodge of products in the ethnic aisle disappears, and rice noodles are sold next to spaghetti. Paye agrees. “I think it will be a thing of the past, a funny thing where we put candles and beans and matzo balls.”.

- Published in Business, Food & Flavor

Ukraine Cidery Destroyed by Russia

Berryland, an award-winning Ukranian cider and mead producer, was destroyed by a bomb in a Russian air raid. The employees escaped and were uninjured.

Owner and oenologist Vitalli Karvyha built his facility six years ago in the Makariv District of Kyiv. Karvyha makes his ciders and meads from local fruits and berries, and raised bees on site for the honey for his mead. His fermented beverages have earned him awards at Vintage Cider World in Germany and the Mazer Cup in Colorado.

Karvyha says he plans to rebuild, updating his status through Berryland Cidery’s Facebook page.

Read more (Broken Palate)

- Published in Business