The Many Sides of Kefir

When Julie Smolyansky began working at her family’s Lifeway Foods business, her father advised her: “Don’t talk about the bacteria. People in America freak out about the bacteria on their food.” So when Lifeway became the first company in the U.S. to put “probiotic” on a label in 2003, it wasn’t a big surprise when customers began calling, asking for the company’s non-probiotic version of kefir.

Americans have come a long way. Consumers today search for the “live, cultured” label on fermented dairy, and gut health is a critical component of the modern diet. Smolyansky and Raquel Guajardo, author/educator, shared their thoughts on kefir during the TFA webinar The Many Sides of Kefir.

“Fermented foods were not part of the American diet, and the way that kefir and fermented foods in general were used in other parts of the world from Asian to Eastern Europe to even India and Mexico, these cultures all have fermented foods as one of their pillars as their foods sources and their health and wellness cultures,” Smolyansky says. “It wasn’t until immigration from all these other countries that we started talking about kimchi or kefir or lassi or you name your cultured kind of special food.”

In the U.S., the average person consumes 9-10 cups of fermented dairy a year. Contrast that statistic with Europe, where the average consumption is 28 cups a month.

“When you’re born consuming it and you’ve developed that taste palette, then it’s very easy to play in the space and have a diet that’s very rich in probiotics and kefir and all sorts of other fermented foods,” Smolyansky says, adding that the situation is changing in the U.S. Now, “people are hungry for it, they want it, once they learn about it, once they taste it, they fall in love with it, they’re hooked.”

Lifeway’s kefir’s sales have soared. The company was valued at $12 million when Smolyansky took over in 2002 — now it’s valued into the hundreds of millions. And even more customers have found kefir during the COVID-19 pandemic, as they adopt healthier lifestyles.

Guajardo has seen her online classes increase during COVID. The Mexico-based educator co-authored the book “Kombucha, Kefir, and Beyond” with Alex Lewin, TFA advisory board member, who moderated the webinar.

“People say ‘You’re crazy, why do you teach what to do at home what you can buy in the supermarket?’ But my business has been growing that way,” she says, adding that health benefits are the main selling point for her classes. “Why would people buy sauerkraut or kefir if you’re not explaining the benefits?”

Dairy Kefir vs. Water Kefir

Guajardo, who makes both dairy kefir and water kefir (also known as tibicos) stresses that the grains used to make each are “totally different.” Kefir grains are living bacteria and yeast microorganisms clumped together with milk proteins and sugars. They are gelatinous and white, almost like cottage cheese. Water kefir grains are also made from living bacteria and yeast microorganisms, but they’re clumped together with sugar and have a translucent, crystal-like appearance.

“Water kefir” is not the appropriate term, Guajardo and Smolyansky agree, instead calling it by its traditional Mexican name, tibicos. And they feel that using kefir or tibicos grains in coconut or almond milk and calling it kefir is also inappropriate. Smolyansky favors using a description like cultured coconut milk or beverage, but not kefir.

The National Dairy Council and Codex Alimentarius, the international food code, both state kefir is a fermented dairy product made from the milk of a lactating mammal. Smolyansky points to the many peer-reviewed studies on kefir, verifying it is full of probiotics and nutrients. Water kefir and non-dairy kefir have not been studied, and can’t guarantee the same health benefits.

“Just by throwing the name onto anything and just bastardizing the definition, we completely dilute any of the research that’s ever been done [on kefir], it would dilute the history, the folklore. So we are very passionate about protecting the name,” Smolyansky says. “My ancestors made sure that kefir survived for 2,000 years, and it’s critical that we don’t dilute it now that it’s having a moment, now that it’s popular.”

Smolyansky’s family emigrated to the United States from the then Soviet Union in the late ‘70s. Her father, Michael, began Lifeway Foods in Chicago in 1986.

“We have to respect the standards and what these definitions mean or it will be the Wild West and people won’t know what they’re buying,” she adds. She shares the labelling of ice cream as an example — ice cream is considered dairy while non-dairy products have other names, like sorbet, gelato or non-dairy frozen dessert.

Can Kefir Grow Like Yogurt?

Yogurt has paved the way for kefir to expand its consumer base in the U.S. Both are fermented dairy products with tangy tastes. But for kefir to achieve widespread, mainstream adoption like yogurt, significant education is needed. Thousands of peer-reviewed studies prove kefir contains a higher concentration of probiotics than yogurt — and a wider range of beneficial bacteria. For kefir to grow, this message needs to reach consumers.

“It’s a different set of microbes,” Lewin says. “Kefir is fermented with yeast and yogurt isn’t. Kefir has a larger family of microbes.”

Smolyansky is passionate that kefir cannot be compared to the products of the major. yogurt companies.

“The yogurt produced in the United States is so over-produced and so over-pasteurized that there’s practically nothing living in it after it’s been processed,” she says. “It’s one of the biggest problems with yogurt in the U.S.”

Lifeway regularly sends their products to be tested for probiotics, measuring Colony Forming Units (CFUs), the active microorganisms in a food product. Smolyansky says eating probiotics is critical in a germ-phobic, antibody-heavy society, where we’re over-sanitizing due to the coronavirus pandemic.

“If our bodies aren’t fighting an outside kind of pathogen, it starts to fight itself,” she says. “One of the ways to counteract this disruption in our microflora is by the use and the introduction of consistently replenishing microflora including diversity of bacteria, a variety of food sources that offer bacteria, the diversity and kind [of bacteria] is always the king. It makes for great food environments in the gut.”

- Published in Business, Food & Flavor

“One Grain to Bind Them All”

A new study on kefir found that the individual dominant species of Lactobacillus bacteria in kefir grains cannot survive in milk on their own. The bacteria need one another to create the fermented dairy drink, “feeding on each other’s metabolites in the kefir culture.”

The research, conducted by EMBL (Europe’s laboratory for life and sciences) and Cambridge University’s Patil group and published in Nature Microbiology, illustrates a dynamic of microbes that had eluded scientists. Though scientists knew microorganisms live in communities and depend on each other to survive, “mechanistic knowledge of this phenomenon has been quite limited,” according to a press release on the research.

“Cooperation allows them to do something they couldn’t do alone,” says Kiran Patil, group leader and author of the paper. “It is particularly fascinating how L. kefiranofaciens, which dominates the kefir community, uses kefir grains to bind together all other microbes that it needs to survive — much like the ruling ring of the Lord of the Rings. One grain to bind them all.”

To make kefir, it takes a team. A team of microbes.

The group studied 15 samples of kefir, one of the world’s oldest fermented food products. Below are highlights from a press release on the published results.

A Model of Microbial Interaction

Kefir first became popular centuries ago in Eastern Europe, Israel, and areas in and around Russia. It is composed of ‘grains’ that look like small pieces of cauliflower and have fermented in milk to produce a probiotic drink composed of bacteria and yeasts.

“People were storing milk in sheepskins and noticed these grains that emerged kept their milk from spoiling, so they could store it longer,” says Sonja Blasche, a postdoc in the Patil group and an author of the paper. “Because milk spoils fairly easily, finding a way to store it longer was of huge value.”

To make kefir, you need kefir grains, which must come from another batch of kefir. They cannot be made artificially. The grains are added to milk, to ferment and grow. Approximately 24 to 48 hours later (or, in the case of this research, 90 hours later), the kefir grains have consumed the available nutrients. The grains have grown in size and number, and are removed and added to fresh milk — to begin the process anew.

For scientists, kefir is more than just a healthy beverage: it’s an easy-to-culture model microbial community for studying metabolic interactions. And while kefir is quite similar to yogurt in many ways – both are fermented or cultured dairy products full of ‘probiotics’ – kefir’s microbial community is far larger, including not just bacterial cultures but also yeast.

A “Goldilocks Zone”

While scientists know that microorganisms often live in communities and depend on their fellow community members for survival, mechanistic knowledge of this phenomenon has been quite limited. Laboratory models historically have been limited to two or three microbial species, so kefir offers – as Patil describes – a ‘Goldilocks zone’ of complexity that is not too small (around 40 species), yet not too unwieldy to study in detail.

Blasche started this research by gathering kefir samples from several sources. Though most were obtained in Germany, they may have originated elsewhere, grown from kefir grains passed down through the years..

“Our first step was to look at how the samples grow. Kefir microbial communities have many member species with individual growth patterns that adapt to their current environment. This means fast- and slow-growing species and some that alter their speed according to nutrient availability,” Blasche says. “This is not unique to the kefir community. However, the kefir community had a lot of lead time for coevolution to bring it to perfection, as they have stuck together for a long time already.”

Cooperation is key

Finding out the extent and nature of cooperation among kefir microbes was far from straightforward. Researchers combined a variety of state-of-the-art methods, such as metabolomics (studying metabolites’ chemical processes), transcriptomics (studying the genome-produced RNA transcripts) and mathematical modelling. These processes revealed not only key molecular interaction agents like amino acids, but also the contrasting species dynamics between grains and milk.

“The kefir grain acts as a base camp for the kefir community, from which community members colonise the milk in a complex yet organised and cooperative manner,” Patil says. “We see this phenomenon in kefir, and then we see it’s not limited to kefir. If you look at the whole world of microbiomes, cooperation is also a key to their structure and function.”

In fact, in another paper from Patil’s group (in collaboration with EMBL’s Bork group) in Nature Ecology and Evolution, scientists combined data from thousands of microbial communities across the globe – from in soil to in the human gut – to understand similar cooperative relationships. In this second paper, the researchers used advanced metabolic modelling to show that the co-occurring groups of bacteria, groups that are frequently found together in different habitats, are either highly competitive or highly cooperative. This stark polarization hadn’t been observed before, and sheds light on evolutionary processes that shape microbial ecosystems. While both competitive and cooperative communities are prevalent, the cooperators seem to be more successful in terms of higher abundance and occupying diverse habitats — stronger together!

The World of Fermented Foods

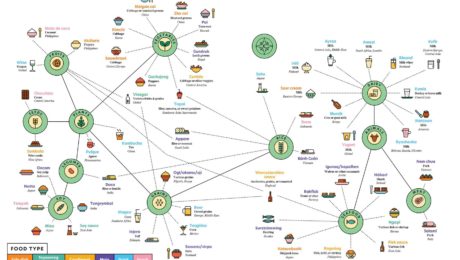

In the latest issue of Popular Science, a creative infographic illustrates “the wonderful world of fermented foods on one delicious chart.” It represents “a sampling of the treats our species brines, brews, cures, and cultures around the world,” and is particularly interesting as it shows mainstream media catching on to fermentation’s renaissance. Fermentation fit with the issue’s theme of transformation in the wake of the pandemic.

Read more (Popular Science)

- Published in Food & Flavor

Though Dairy Industry Sales Continue to Decline, Specialty Cheese Market Grows

Cheese making is a craft steeped in tradition. But as industry-altering trends emerge — like innovative ingredients, plant-based dairy, sustainable operations — how can cheese creameries compete?

At the Winter Fancy Food Show, heads of two specialty cheese companies in Northern California shared their insight about innovations and trends in specialty cheese.

Consumers are shunning processed cheese for specialty, small-scale, fermented, farmstead brands. Research from Winsight Grocery Business shows that specialty cheese sales are growing. Though sales of dairy-based cheese dipped in 2019, specialty cheese sales are up 2%.

Using Innovative Ingredients

“In cheese, the great thing is that tradition is always up-to-date,” says Manon Servouse, brand manager for Marin French Cheese. Founded in 1865, Marin French Cheese still uses the traditional art of French cheese making, but “we add innovation with inspiration from our local area” in Marin County, California, where Marin’s operations are located.

Marin’s new ingredients include adding jalapeno, truffle and ash coating.

Laura Chenel cheese, meanwhile, is also experimenting with new flavors. The goat cheese brand based in Sonoma County, California adds bacterial cultures to their goat milk, a fermentation process that produces a distinct flavor. Laura Chenel’s newest cheese won a Good Food Award this year. The aged goat cheese, called Crottin, develops a specific rind on the cheese, which aids the cheese’s flavor.

Competing with Plant-Based Cheese

Eric Barthome, CEO of Laura Chenel, says though plant-based cheese is becoming a force in the food industry, plant-based is not their audience.

“The real cheese lovers like cheese made with milk,” Barthome says. “And that’s what we want to do. We’ve been working on the quality of the milk for so long that, yes, there’s room for new products and new cheese made with plant-based products. However, our credo is really to continue to make the best milk to make the best…real goat cheese we can make.”

Plant-based foods are becoming mainstream. U.S. retail sales of plant-based foods grew 11% the past year, according to research by the the Plant Based Food Association and Good Food Institute. Sales of the total plant-based market was $4.5 billion. That figure goes beyond cheese, and includes plant-based milks, cheese, yogurt, ice cream and meat. Plant-based meats are the leading sales driver for plant-based products.

Though plant-based cheese sales are growing, milk-based cheese topped $18 billion in sales in 2019, with specialty cheese sales growing the fastest.

Manon says people are turning to plant-based products because they’re concerned about animal welfare. She noted, at Marin French Cheese, they work with two small creameries to get their milk to monitor the health of the animals. They run small-scale to produce high-quality milk.

Importance of Sustainability

Running an environmentally sustainable creamery is key to successfully operating a modern cheese creamery.

Laura Chenel was sold to the French Triballat family in 2006, and the new leaders decided to build a new creamery in Sonoma County. The new facility reduced the use of natural resources by using water more efficiently, utilizing solar energy, implementing natural lighting and retooling waste management. The new creamery is the only LEED gold certified cheese creamery in the world.

“Very important to us is respect for the environment, respect for tradition and respect for the animals,” Barthome says.

- Published in Business

Miyoko’s Sues California Ag Department Over Fermented Vegan Butter

Miyoko’s has filed a lawsuit against the California Department of Food and Agriculture, after the state agency sent a letter demanding the plant-based creamery stop using the word “butter” on the Miyoko’s butter, a cashew cream that is fermented with live cultures. The agriculture department says the term butter is restricted to products containing at least 80% milk fat. The department also told Miyoko’s to drop the terms “lactose-free,” “hormone-free” and “cruelty-free” from their packaging because “the product is not a dairy product.” In addition, the department also wants Miyoko’s to remove an image on their website of a woman hugging a cow because “dairy images or associating the product with such activities cannot be used on the advertising of products which resemble milk products.”

In response, Miyoko’s points out that the front of their butter label uses the terms “Made from plants,” “Vegan” and “Cashew Cream,” so consumers are not confused whether or not the butter is made from cow’s milk. A change would cost the company $1 million. Miyoko’s added: “The Milk and Dairy Food Safety Branch may be tasked with supporting the State’s agricultural industries, but it is prohibited by the First Amendment from taking sides in a contentious national debate on the role of plant-based foods and leveraging its power to censor one emerging industry’s speech in order to protect a more powerful and entrenched industry.”

Read more (Food Navigator)

- Published in Business, Food & Flavor

New Food Laws Taking Effect in 2020

Thousands of new state laws were passed across America this year, and dozens affect fermentation businesses — small and large — as well as home fermenters.

Government agencies are loosening some strict health code and alcohol regulations, laws that made running an artisanal business difficult. There are also new opportunities being created that allow craft breweries to expand their operations, such as entertainment districts where beer can be sold and enjoyed legally.

Read on for the breakdown of 2019 food laws passed in each state

Alaska

SB16 — Expands state alcohol licenses to include recreational areas. After the Alaska Alcoholic Beverage Control Board began cracking down on alcohol licenses in 2017, several recreational sites were denied licenses to sell alcohol. The bill, known as “Save the Alaska State Fair Act,” now expands license types to the state fair, ski areas, bowling alleys and tourist operations.

Arizona

HB2178 — Removes red tape for small ice cream stores and other milk product businesses to manufacture and sell dairy products. The bill, called the “Ice Cream Freedom Act,” allows smaller mom and pop businesses to make milk-based products without complying with state regulations designed for large dairy manufacturers.

Arkansas

HB1407 — Prohibits false labeling on agricultural products edible by humans. That includes misleading labels, like labeling agricultural products as a different kind of food or omitting required label information.

HB1556 — Ends the “undisclosed and ongoing investigations” of the Alcoholic Beverage Control Board, the Alcoholic Beverage Control Division, and the Alcoholic Beverage Enforcement Division.

HB1590 — Limits the number off-premise sales of wine and liquor in the state to one permit for every 7,500 residents in the county or subdivision. Small farm wines are the exception to the new law.

HB1852 — Allows a microbrewery to operate in a dry county as a private club, without approval from the local governing body.

HB1853 — Amends the Local Food, Farms, and Jobs Acts to increase the amount of local farm and food products purchased by government agencies (like state parks and schools).

SB348 — Establishes a Hard Cider Manufacturing Permit. Cider brewers can apply for the annual $250 permit, authorizing the sale of hard cider. Producers may not sell more than 15,000 barrels of hard cider a year.

SB492 — Establishes temporary or permanent entertainment areas in wet counties where alcohol can be carried and consumed on the public streets and sidewalks.

California

AB205 — Revises the definition of beer to mean that beer may be produced using “honey, fruit, fruit juice, fruit concentrate, herbs, spices, and other food materials, and adjuncts in fermentation.”

AB377 — A follow-up to the state’s landmark California Homemade Food Act in 2018, the new bill would clarify the implementation process of last year’s bill. The California Home Food Act made it legal for home cooks to operate home-based food production facilities. The law, though, was only enacted if a county’s board of supervisors voted to opt-in to offer the permits. Only one county in California has opted in (Riverside). County health officials are avoiding singing on the bill because of potential food safety risks.

AB619 — Permits temporary food vendors at events to serve customers in reusable containers rather than disposable servingware. The “Bring Your Own Bill” also clarifies existing health code, allowing customers to bring their own reusable containers to restaurants for take-out.

AB792 — Establishes a minimum level of recycled content (50%) in plastic beverage bottles by 2035. The world’s strongest recycling requirement, the law would help reduce litter and boost demand for manufacturers to use recycled plastic materials.

AB1532 — Adds instructions on the elements of major food allergens and safe handling food practices to all food handler training courses.

Connecticut

HB5004 — Raises minimum wage to $15 by 2023.

HB6249 — Charges 10 cents for single-use plastic bags by 2021.

HB7424 — Raises sales tax from 6.35% to 7.35% for restaurant meals and prepared foods sold elsewhere, like in a grocery store. Also repeals the $250 biennial business entity tax.

Delaware

HB130 — Bans single-use plastic bags by 2021.

SB105 — Raises minimum wage to $15 by 2024.

HB125 — Facilitates growth and expansion of craft alcoholic beverage companies, raising amount of manufactured beer to 6 million barrels.

Florida

SB82 — Prohibits a municipality from regulating vegetable gardens on residential properties.

Idaho

HB134 — Regulates where beer and wine can be served, now including public plazas.

HB151 — Charges licensing fees for temporary food establishments based on the number of days open. Fees will gradually increase through 2022.

Illinois

HB3018 — Amends Food Handling Regulation Enforcement Act, requiring a restaurant prominently display signage indicating a guest’s food allergies must be communicated to the restaurant.

HB3440 — Allows customers to provide their own take-home containers when purchasing bulk items from grocery stores and other retailers.

HB2675 — An update to state liquor laws, the bill removes hurdles for craft distilleries to operate. Craft distilleries would be allowed to more widely distribute their products themselves, rather than distributing under the state’s three-tier liquor distribution system that separates producers, distributors and retailers.

SB1240 — Imposes a 7 cent tax on each plastic bag at checkout, with 2 cents staying with the retailers. The remaining 5 cents per bag would fix a statewide budget deficit.

Indiana

HB1518 — Creates a special alcohol permit for the Bottleworks District. The $300 million, 12-acre urban mixed-use development in the Coca-Cola building will serve as a culinary and entertainment hub in downtown Indianapolis.

Iowa

SF618 — Increases the limit on alcohol in beer from 5% to 6.25%.

SF323 — Canned cocktail and premixed drinks served in a metal can, up to 14% alcohol by volume, will now be regulated like beer.

Kentucky

HB311 — Requires proper labeling of cell-cultured meat products that are lab produced.

HB468 — Expands defined items permitted for sale by home-based processors.

Louisiana

HR251 — Designates week of September 23-29 as Louisiana Craft Brewer Week.

SB152 — Establishes definition for agriculture products. Prohibits anyone from mislabeling a meat edible to humans.

SR20 — Designates week of September 3-9th as Louisiana Craft Spirits Week.

Maine

LD289 — Prohibits stores from selling or distributing any disposable food containers that are made entirely or partially of polystyrene foam (Styrofoam).

LD454 — Provides funding and staffing needed to give local students and nutrition directors the resources needed to purchase and serve locally grown foods.

LD1433 — Bans two toxic, industrial chemicals (phthalates and PFAS) from food packaging. Maine becomes first state in the nation to ban the two chemicals.

LD1532 — Bans all single-use plastic bags in the state. Law will be enacted by April 2020, at which time shoppers can pay 5 cents for a plastic bag. Maine is the fourth state to pass a ban, joining California, New York and Hawaii.

LD1761 — Increases amount of barrels craft beer and hard cider manufacturers can produce in a year. The cap increased from 50,000 gallons to 930,000 gallons (approximately 30,000) barrels. The law also makes it easier for a small brewery to get out of a contract with a large distributor.

Maryland

SB596 — Defined mead as a beer for tax purposes.

HB1010 — Updates state beer laws by increasing taproom sales, production capabilities, self-distribution limits and hours of operation. Known as the Brewery Modernization Act, the law is aimed to create jobs and increase economic impact.

HB1080 — No restrictive franchise law provisions for brewers that produce 20,000 barrels a year or less.

HB1301 — Sales tax will be collected on Maryland buyers from online sellers, helping small businesses compete with online retailers.

Massachusetts

HB4111 — Raises minimum wage by 75 cents a year until it reaches $15 in 2023.

Michigan

HB4959 — Gives state Liquor Control Commission the power to seize beer, wine, mixed spirit and mixed wine drinks, in order to inspect for compliance with the state’s extraordinarily detailed and complex “liquor control” regulatory and license regime. Bill also repeals a one-year residency requirement imposed on applicants for a liquor wholesaler license, after the U.S. Supreme Court invalidated a similar Tennessee law as a violation of the U.S. Constitution’s commerce clause.

HB4961 — Prohibit licensed liquor manufacturers from requiring licensed wholesalers to give the manufacturer records related to the distribution of different brands, employee compensation or business operations that are not directly related to the distribution of the maker’s brands.

SB0320 — Eliminates mandate that businesses with a liquor license must post a regulatory compliance bond with the state.

Minnesota

HF1733 — Updates the state’s omnibus agriculture policy law, including: create a custom-exempt food handlers license for those handling products not for sale; extend the state’s Organic Advisory Task Force by five years; allow the agriculture department to waive farm milk storage limits is the case of hardship, emergency, or natural disaster, and modify milk/dairy labelling requirements; modify labelling for cheese made with unpasteurized milk; expand the agriculture department’s power to restrict food movement after an emergency declaration; modify eligibility and educational requirements for beginning farmer loans and tax credits.

Mississippi

SB2922 — Prohibits labeling non-meat products as meat, like animal cultures, plants and insects.

Montana

HB84 — Changes tax on wine to 27 cents per liter, and a tax on hard cider at 3.7 cents per liter.

SB358 — Raises alcohol license fee for resorts from $20,000 to $100,000 each.

Nebraska

LR13 — Establish and enforce definitions for plant-based milk and dairy. Proper product labeling would be enforced for milk and dairy food products that are “truthful, not misleading, and sufficient to different non-dairy derived beverages and food products.”

Nevada

SB345 — Authorizing pubs and certain wineries to transfer certain malt beverages and wine in bulk to an estate distillery; authorizing a wholesale dealer of liquor to make such a transfer; authorizing an estate distillery to receive malt beverages and wine in bulk for the purpose of distillation and blending; revising when certain spirits that are received or transferred in bulk are subject to taxation.

New Hampshire

HB598 — Establish a commission to study beer, wine, and liquor tourism in New Hampshire. The commission will specifically develop a plan for tourism, including establishing tourist liquor trails with signage along the highway, suggest changes to liquor laws that would enhance tourist experiences at state wineries, breweries and liquor manufacturers and suggest how to allow a “farm to table” dinner featuring New Hampshire produced food items and local alcoholic beverages.

HB642 — Defining ciders with alcohol content greater than 6% (but no more than 12%) as specialty beers.

New Jersey

A15 — Raises the state minimum wage to $15 an hour by 2024, raising in $1 increments every year.

SB1057 — Establishes a loan program for capital expenses for vineyards and wineries in New Jersey.

New Mexico

SB149 — Change name of Alcohol and Gaming commission to Alcoholic Beverage Control Division.

SB413 — Allows breweries to: sell beer at 11 a.m. on Sundays; have private celebration permits for events like weddings and graduation parties; no minimum standards (50 barrels a year or 50 percent of all sales coming from beer brewed on site) for businesses to hold a small brewer license; eliminate excise tax, with breweries paying $.08 per gallon on the first 30,000 barrels produced.

New York

AB6019 — Encourage expansion of fresh fruits and vegetables in community gardens.

AB 8419 — Enacts the farm laborers fair labor practices act, granting collective bargaining rights, workers’ compensation and unemployment benefits to farm laborers

SB578 — New option for any brewer or distiller to file their taxes electronically.

SB1263 — Allows mead (honey-based wine) and braggot brewers to apply for a state farm meadery license. Similar to a farm winery, brewery, distillery and hard cider license, the law recognizes the boom in the craft beverage industry in the state. As a licensed meadery, mead-makers who use 100% New York honey will quality for additional benefits: offer onsite tastings, sell products by glass in their tasting rooms, sell takeout packages, offer other New York farm-produced beer, wine, cider and spirits.

SB3281 — Amends current Alcoholic Beverage Control law, authorizing the sale of cider, mead, braggot and wine at games of chance.

SB4812 — Amend current Alcoholic Beverage Control law, permitting New York State Fair concessionaires to issue a temporary State Liquor license to sell alcoholic beverages on the state fairgrounds.

SB5675 — Amend current Alcoholic Beverage Control law, authorizing issue of liquor license to a business located within 200 feet of a religious institution in multiple counties.

North Carolina

HB363 — Adds a third tier to the craft beer system — mid-level brewers. Now brewers can self-distribute 50,000 barrels of product. Called North Carolina’s Craft Beer Distribution & Modernization Act, the law also expands liquor licensing to college-level NCAA events, where drinking is currently unregulated. Currently, the law only applies to beer and wine.

North Dakota

HB1190 — Amend code to allow a winery to be issued a license without the previous requirements for how much wine is allowed to be produced in a year.

HB2079 — Amends code regarding pasteurized milk, authorizing a state milk sanitation rating and sampling surveillance officer for the rating and certification of milk and dairy products.

SB2343 — Adds microbrew pub as an official brewer licensee under city code. A microbrew pub may manufacture on the licensed premises, store, transport, sell to wholesale malt beverage licensees, and export no more than 10,000 barrels of malt beverages annually; sell malt beverages manufactured on the licensed premises; and sell alcoholic beverages regardless of source to consumers for consumption on the microbrew pub’s licensed premises. A microbrew pub may not engage in any wholesaling activities.

Oklahoma

SB544 — Requires limits on licensing fees for businesses who only sell at farmers markets.

SB608 — Requires manufacturers of the top 25 wine and spirit brands to sell their products to any state-licensed wholesaler. The law requires equal sales of the top brands, potentially creating a competitive market. The matter is currently being heard by the Supreme Court, as some businesses believe this eliminates a free market.

Oregon

HB3239 — Removes the limit of how many on-premises sales licenses that a distillery can have.

SB247 — Adds containers for kombucha and hard seltzer to the types of beverage containers covered by Oregon’s Bottle Bill. The Bottle Bill establishes laws that require stores and distributors to accept certain empty beverage containers and pay a 10-cent refund value for each container.

Pennsylvania

HB947 — Amends the Liquor Code established in 1951, to provide further definitions for licenses and regulations for liquor, alcohol and malt and brewed beverages.

Rhode Island

SB620 — Increases the amount of malt beverages that could be sold on premises at a craft brewery.

South Dakota

SB68 — Prohibits labeling cell-cultured protein as meat.

SB124 — Allows a retailer, carrying their own merchandise purchased from a wholesaler, to transport alcoholic beverages to the retailer’s licensed business.

Tennessee

SB358 — Requiring unpasteurized butter sold to the public must bear a warning on the package label. The warning was approved by the legislature and added to state code.

SB 1082 — Allows premises authorized to serve wine to also serve high alcohol content beer. Requires training for applicants for server permits, consisting of no less than 3.5 hours of alcohol awareness training. Clarifies premises authorized to sell alcoholic beverages to include tables and chairs outside the front wall of the licensee’s building.

Texas

HB1545 — Allows craft breweries to sell beer to-go in Texas. Though wineries have been able to sell to customers for years, breweries have been unable because of alcohol beverage code written in 1935.

HB4542 — Adds brewpub to local tax code for businesses involved in manufacturing and distribution of alcoholic beverages.

SB572 — Expands state cottage food law to include opportunities for people to make low-risk products in home kitchens and sell them to consumers. Cottage food products now include fermented products, pickled vegetables, acidified canned goods and frozen fruits and vegetables.

Utah

HB33 — Defines the term “produce” as a food that is: fruit, vegetable, mix of intact fruits and vegetables, mushroom, sprout from any seed source, peanut tree nut, or herb and a raw agricultural commodity. Known as the Utah Wholesome Food Act, the law also expands the definition of “food establishment” to include farms.

HB453 — Defines specific business that can have a recreational beer license, specifically banning karaoke bars and ax-throwing businesses from getting a license.

SB132 — Drops 3.2% beer in favor of 4% brew, allowing the stronger beers to be sold in grocery and convenience stores. Stronger beers would still be sold in liquor stores operated by the Utah Department of Alcoholic Beverage Control.

Vermont

SB113 — Bans single-use plastic bags on July 1, 2020 and requires a fee of at least 10 cents for paper bags. Bans polystyrene foam contains, plastic stirrers and plastic straws.

Virginia

HB1960 — Allows distillers to product and market low alcohol volume products.

HB2634 — Makes every “dry” county in the state a “wet” county. Allows sale of mixed beverages by licensed restaurants (and the Board of Directors of the Virginia Alcoholic Beverage Control Authority) by any municipality. If the county, town or district holds a referendum and the majority vote prohibits alcohol sales, then alcohol sales are banned in that jurisdiction.

- Published in Business

Preventing Chronic Health Conditions with Fermented Dairy

Health and wellness professionals are recommending food and drink to aid chronic health conditions with a centuries-old cooking legacy – fermented dairy.

“Fermentation is back. In fact, we have over 10,000 years of fermentation history and we aren’t done because, right now, it is a hot culinary and nutrition topic,” said Andrew Dole, chef, dietitian and owner of BodyFuelSPN. “Today, fermented foods have found a resurging popularity. The combination is based in the unique taste profile, the artisan aura, and the health benefits that have secured fermented foods in the top spots with trend spotters.”

Dole spoke at the “Get Cultured on Fermented Dairy Foods” webinar with National Dairy Council representatives Sally Cummins and Chris Cifelli. Using independent, clinical studies, the trio highlighted how fermented dairy – especially dairy with the “nutrition powerhouse” of milk – can boost gut health, decrease inflammation and reduce the risk of Type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease.

Fermented Food Just as Important as Fiber

Fiber is the shining star of the health world to aid the complex gut microbiome, but fermented food and drink are equally as important said Cifelli, PhD, vice president of Nutrition Research for the National Dairy Council.

“When we think about food, we think about fiber and we know the benefits of fiber in terms of helping our microbiota, but we also don’t think about getting those live and active cultures the same way and we really should,” he said.

The microorganisms that come from fermented foods are just as critical as fiber. He pointed out the Live & Active Culture seal as an important indicator of how to find dairy products with good bacteria. That seal – a voluntary seal by the National Yogurt Association – identifies a yogurt product that contains at least 10 million cultures per gram at the time of manufacturing. Some yogurt brands are heat treated after fermentation, killing any good bacteria. The seal is “the industry validation of the presence and activity of significant levels of live cultures,” according to the National Yogurt Association.

Fermented Dairy as Preventative Food

The human digestive tract contains 100 trillion bacterial cells. But modern practices like sanitation, antibiotics, processed food, c-section births and baby formula use have altered microbiota composition. Cifelli said scientists still don’t understand whether disease is a cause or consequence of an imbalance of good and bad bacteria (known as dysbiosis).

Fermented dairy foods, though, are linked to numerous positive health benefits. As plant-based milk products become increasingly popular, Cifelli noted the research all studied dairy milk products. He called milk “a foundational ingredient in all fermented dairy.” The essential nutrients in milk give it a unique health profile, the reason the Dietary Guidelines for Americans recommend three daily servings of dairy food.

Diabetes and cardiovascular disease – two of the major disease plaguing Americans today – both have beneficial health outcomes when a patient consumes fermented dairy products.

Diabetes:

- American Journal of Clinical Nutrition: Consuming more dairy products reduces risk for Type 2 Diabetes by 7%. Eating 80 grams of yogurt daily compared to 0 grams of yogurt daily reduces risk for Type 2 Diabetes by 14%.

- PLOS One (Public Library of Science): Eating 30 grams of cheese daily and 50 grams of yogurt daily reduces risk of Type 2 Diabetes by 6%.

- BMC Medicine: One serving of yogurt a day is associated with a 17% reduced risk for Type 2 Diabetes.

Cardiovascular disease:

- American Journal of Clinical Nutrition: A high daily intake of regular-fat cheese for 12 weeks did not alter LDL cholesterol levels of metabolic syndrome, both risk marks of cardiovascular disease risk.

- European Journal of Clinical Nutrition: Cheese consumption reduces the risk of: cardiovascular disease by 10%, coronary heart disease by 14% and stroke by 10%.

- Journal of Hypertension: Higher total dairy intake (3-6 servings a day), especially in the form of yogurt (at least 5 servings a week), associated with a lower risk of incidence of high blood pressure in middle-aged and older adult men and women.

- American Journal of Hypertension: Hypertensive men and women who consumed 2 servings per week of yogurt, especially while eating a healthy diet, were at a lower risk for developing cardiovascular disease.

Cifelli called the studies “significant. He added: “there’s been a huge body of evidence looking at dairy guidelines and (diabetes and cardiovascular disease) risk. … We’re really scratching the surface of what (fermented foods) means for health in the long run.”

Incorporating Fermented Foods

Dole, a chef, said you’re “bringing science to the table when it comes to fermented dairy foods.” Fermented foods enhance food by providing an increased concentration of vitamins, adding delicious flavor and increased texture. He shared multiple recipes using yogurt. Yogurt can be used for dip, spread, sauces, dressings, soups and marinade.

“Yogurt is a culinary powerhouse, from a chef’s perspective. We’re always looking for what has the most bang for its buck in versatility, and yogurt is ready-made everything,” he said.

“The (yogurt) fermentation process from a culinary perspective that creates that lactic acid, it works to tenderize meat. Indians have used it in their tandoor for a really long time. Another reason, the sugar caramelizes…and it completely changes the flavor profile and the color. And we get the unique taste of that yogurt tang, it imparts a different balance and depth, which is something home cooks can struggle to get.”

- Published in Health

NYT: Does Kombucha Health Claims Live Up to Hype?

The New York Times asks: are there benefits to drinking kombucha? The article explores hard kombucha and the health claims of drinking the fermented tea. “But for those interested in integrating a variety of microbes into their diet, Dr. Emeran Mayer, author of ‘The Mind-Gut Connection,’ recommends doing so naturally. ‘I personally drink it occasionally,’ he said. Instead of using pills or supplements, he said, alternate different fermented foods, including sauerkraut, kimchi, cultured milk products, and, yes, kombucha.

Read more (New York Times)

- Published in Food & Flavor, Health

New Supplier in Raw, Clean Pet Food Category: Fermented Pet Food

Raw, clean ingredient pet food is the fastest growing part of the pet food category. More pet food brands are inventing ways to feed their pets unprocessed, organic ingredients. A new article highlights Answer Pet Food, the first (and so far only) fermented raw pet food supplier. Answers Pet Food utilized kombucha, raw cultured whey, cultured raw goat’s milk and kefir in their pet food products. Their products include fermented chicken feet and fermented pig feet. Answers Pet Food says: “Fermentation is the most natural and effective way for us to make our products as safe and healthy as possible. … Our raw fermented pet foods are formulated to create a healthy gut. Fermentation supports healthy immune function by increasing the B-vitamins, digestive enzymes, antioxidants, and lactic acid that fight off harmful bacteria. It’s also the ultimate source of probiotics.”

Read more (Pet Product News)

- Published in Business

Should a Fermented Process Get a Patent? PepsiCo Files Oat Flour and Dairy Co-Ferment Patent

Should a fermented food process need a patent? PepsiCo has filed a patent to ferment oat flour and dairy milk together. PepsiCo-owned Quaker Oats is creating a “spoonable or drinkable” clean-label product comparable to yogurt. The process involves co-fermenting a grain, dairy and a set of metabolites. This patent is unique because, while there are existing food products that combine unfermented and fermented dairy and grains, none co-ferment grain and dairy at the same time. In their application, PepsiCo notes that consumers are increasingly consuming fermented food products for health benefits.

Read more (World Intellectual Property Organization)

- Published in Science