Food and Beverage Laws Passed in 2021

After the Covid-19 pandemic shortened their legislative sessions last year, lawmakers across the 50 states had a productive year in 2021. State leaders were able to pass hundreds of bills relating to food, beverages and food service.

Numerous new laws were aimed at helping restaurants survive — permitting permanent outdoor dining spaces, allowing carryout food services and to-go alcohol sales. Many of these regulations had been enacted in 2020 as temporary, emergency measures to aid restaurateurs, but expired this year.

This year was also big for cottage food laws. As more people experimented in their home kitchens during the pandemic, there was pressure to modernize cottage food laws. Over half the states updated their laws in 2021, regulating sales of homemade food.

Below are the key food, beverage and food service laws passed this year in, alphabetically, Alabama through Maryland. We’ll feature the balance of the states — Massachusetts to Wyoming — in TFA’s next newsletter (January 12, 2022).

Alabama

HB12 — Extends protections granted for cottage food businesses to include roasted coffees and gluten-free baking mixes.

HB539 — Increases the amount of alcohol which breweries and distilleries can sell to customers for off-premise consumption.

SB126 — Allows licensed state businesses to deliver wine, beer and spirits to customers’ homes.

SB160 — An update to Alabama’s cottage food law, SB160 allows for most non-perishable foods to be made in home-based food businesses without commercial licenses (instead of just only baked goods, jams/jellies, dried herbs and candies). It also removes the $20,000 sales limit for home-based food businesses. It also allows online sales and in-state shipping of products.

SB167 — Permits Alabama wineries to sell directly to consumers at special events.

SB294 — Authorizes wine manufacturers to sell directly to retailers without a distributor.

SB397 — Allows opening of wineries in Alabama’s 24 dry counties. The wineries will be allowed to produce and operate in a dry county, but they may not sell on premise.

Alaska

HB22 — Legalizes herd share agreements for the distribution of raw milk in the state.

Arizona

HB2305 — Amends law to allow two or more liquor producers, craft distillers or microbrewery licenses at one location.

HB2753 — States that licensed producers, craft distillers, brewers and farm wineries are subject to rules and exemptions prescribed by the FDA. Exempts production and storage spaces from state regulation.

HB2773 — Allows bars, liquor stores and restaurants to sell cocktails to-go.

HB2884 — Exempts alcohol produced on premise in liquor-licensed businesses from food safety regulation by the Arizona Department of Health Services, which adds rules regarding production, processing, labeling, storing, handling, serving, transportation and inspection. Specifies that this exemption includes microbreweries, farm wineries and/or craft distilleries.

Arkansas

HB118 — Permits the sale of cottage foods over the internet. Interstate sales are permitted if the producer complies with federal food safety regulations.

HB1228 — Allows for municipalities in dry counties to apply to be an entertainment district, just like in wet counties.

HB1370 — Establishes mead as an allowed liquor for a small farm winery — and allows wineries to ship mead. Also allows for mead to be taxed in the same manner as wine.

HB1426 — Establishes the Arkansas Fair Food Delivery Act, stating that a food delivery platform (like UberEats) must have an agreement with a restaurant or facility to take food orders and deliver food prepared.

HB1763 — Allows distilleries to self distribute their own products and allows out-of-state, direct-to-consumer shipments.

HB1845 — Restricts advertising alcohol in microbrewery-restaurants in dry counties.

SB248 — Replaces Arkansas’ cottage food law with the Food Freedom Act. Allows all types of non-perishable foods to be sold almost anywhere without a food safety license and certification, including grocery stores and retail shops.

SB339 — Allows permitted restaurants to sell on-the-go alcoholic beverages.

SB479 — Allows restaurants with alcohol beverage permits to expand outdoor dining without approval of the Alcoholic Beverage Control Division.

SB554 — Authorizes beer wholesalers to distribute certain ready-to-drink products.

SB631 — Authorizes a hard cider manufacturer to deliver hard cider.

California

AB61 — Allows restaurants and bars with alcohol licenses that added temporary, outdoor sidewalk dining spaces during the Covid-19 pandemic to continue serving alcohol in these spaces.

AB239 — Allows wineries to refill wine bottles at off-site tasting rooms, similar to breweries reusing growlers

AB286 — Requires third-party delivery companies to itemize cost breakdowns of delivery transactions to both restaurants and customers.

AB425 — Updates regulations regarding definitions, assessments, fees and funding mechanisms for the Dairy Council of California.

AB831 — Mandates that all labels on cottage food must include the disclaimer “Made in a Home Kitchen” along with the producer’s county and cottage food permit number.

AB941 — Establishes a grant program for counties to apply for farmworker resource centers, supplying farmworkers and their families information on education, housing, payroll, wage rights and health services.

AB962 — Requires the creation of a returnable bottle system in the state by 2024. Allows recyclable bottles to be washed and refilled by beverage producers rather than being crushed for recycling.

AB1144 — Updates California’s outdated cottage food laws, raising sales limit to either $75,000 (Class A permits) or $150,000 (Class B permits) and simplifying the approval process for sampling cottage food products. Also allows homemade food to be sold online.

AB1200 — By 2023, no eatery in California is permitted to distribute or sell food packaging that contains regulated perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances or PFAS. Manufacturers of food packing must use the least toxic alternative when replacing their food packaging. Food packaging includes food or beverage containers, take-out containers, liners, wrappes, eating utensils, straws, disposable plates, bowls and trays.

AB1267 — Allows licensed manufacturers, distributors and sellers of alcoholic beverages to donate a portion of beverage purchases to a nonprofit.

AB1276 — Requires California eateries to only give take-out customers single-use utensils and condiment packets if they ask for them.

AR15 — Establishes Nov. 22 as Kimchi Day in the state.

SB19 — Allows wineries to open additional off-site tasting rooms without applying for a new license (former law allowed for only one off-site tasting room).

SB314 — Allows restaurants and bars that added temporary, outdoor sidewalk dining spaces during the Covid-19 pandemic a one-year grace period to apply for permanent expansion.

SB389 — Allows restaurants and bars to serve to-go alcohol alongside a meal.

SB453 — Establishes an Agricultural Biosecurity Fund specifically for the California State University system’s Agricultural Research Institute. The California State University’s 23 campuses and 8 off-campus branches can then use that fund to apply for grants related to supporting research on agriculture biosecurity, best practices around infectious agents hurting the state’s animal herds and plant crops.

SB517 — Authorizes a licensed beer manufacturer who obtains a beer direct shipper permit to sell and ship beer directly to a resident of the state for personal use.

SB535 — Makes it unlawful to manufacture or sell imitation olive oil in the state. Also restricts using “California Olive Oil” on a label unless 100% of the oil is derived from olives grown in California. The label can also only share that the oil comes from a specific region of California if at least 85% of the olives were grown in that region.

SB721 — Establishes Aug. 24 as California Farmworker Day.

Colorado

HB1027 — Extends sales of to-go alcohol from licensed restaurants and bars to 2026.

HB1162 — The Plastic Pollution Reduction Act, the law bans single-use plastic bags and containers made from polystyrene (styrofoam) for restaurants and other retailers by 2024. All stores will also implement a 10-cent bag fee for plastic and paper bags by 2023.

SB35 — Prohibits third-party restaurant delivery services from cutting pay to a driver to comply with fee limits. Also prohibits third-party delivery services from putting restaurants on their platforms without the eateries’ permission.

SB235 — Sends the Department of Agriculture $5 million for energy efficiency and soil health programs.

SB270 — Allows more Colorado wineries, cideries and distillers to attain a pub license and sell a variety of food in addition to their craft beverage. Current law puts small limits on the amount of craft drink made for a brewery to sell food, leaving out larger Colorado producers.

Connecticut

HB5311 — Enables permitted transporter to sell and serve alcohol on boats, motor vehicles and limousines.

HB6610 — Codifies expanded outdoor dining, allowing municipalities to close off streets and sidewalks for outdoor restaurant dining space.

SB894 — Allows patrons to pour their own alcoholic drinks at restaurants and bars. Will allow self-pour automated systems to be used in the state’s dining establishments.

HB6580 — Expands food agricultural literacy programs of study and community outreach, by increasing certification, education and extension programs with rural suburban and urban farms for students in grades Kindergarten through 12th grade.

Delaware

HB1 — Allows restaurants to continue selling to-go alcohol beverages. The bill also allows restaurants and bars to continue using outdoor dining spaces originally used during the Covid-19 pandemic.

HB46 — Allows brewery-pub and microbrewery license holders to brew, bottle and sell hard seltzers and other fermented beverages made from malt substitutes. Also includes a specific tax on fermented beverages.

HB143 — Reduces the amount of licensed taprooms to only one taproom within a ½ mile from another taproom.

HB212 — Increases minimum thickness for plastic bags (used by grocery stores and restaurants) to qualify as a reusable bag from 2.25 mils to 10 mils.

SB46 — Allows wedding venues and event centers licensed as bottle clubs to allow customers to bring alcoholic beverages on premise.

Florida

HB751 — Authorizes issuance of special licenses to mobile food vehicles to sell alcohol beverages within certain areas.

HB1647 — Allows more Orlando eateries to sell alcohol. Allows eateries with a smaller footprint (80-person capacity; formerly 150-person capacity) to sell beer, wine and spirits in six additional Orlando Main Street Districts.

SB46 — Increases production limits for distilleries from 75,000 gallons a year to 250,000 gallons. Eliminates the “six bottles per person per brand per year” requirement. Also allows craft distilleries to qualify for a vendor’s license to conduct tastings at Florida’s fairs, trade shows, farmers markets, expositions and festivals.

SB148 — Authorizes restaurants or bars also holding a public food service license to sell or deliver alcoholic beverages in sealed, to-go containers.

SB628 — Establishes a new program, the Urban Agriculture Pilot Project, to distinguish between traditional rural farms and emerging urban farms. Exempts farm equipment used in urban agriculture from being stored in certain boundaries.

SB663 — Updates Florida’s cottage food law to allow shipping of products, and raises the sales limit for shipped cottage food from $50,000 to $250,000. The bill also prevents counties or cities from banning cottage food businesses (Ed. note: Florida’s largest county, Miami-Dade, prohibits cottage food businesses).

SR2041 — Establishes a Food Waste Prevention Week in the state to acknowledge the importance of conserving food and preventing food waste.

Georgia

HB273 — Allows local municipalities to pass an ordinance, resolution or referendum election to authorize allowing a liquor store to open in their jurisdiction

HB392 — Allows a person to have a mixed cocktail or draft beer from the hotel delivered to their room by a hotel employee.

HB498 — Expands eligibility requirements for the state’s tax exemption for agricultural equipment and farm products. Any family-owned farm entity (defined as two or more unrelated, family-owned farms) can now share equipment, land and labor without losing ad valorem tax exemptions enjoyed by stand-alone family farms.

HB676 — Creates a legislative advisory committee on farmers’ markets (Farmers’ Markets Legislative Advisory Committee), made up of five members from the state’s Senate and House.

SR155 — Recognized February 17 as State Restaurant Day.

SB219 — Permits small brewers to sell alcohol for consumption on their premise. Allows state’s breweries to transfer beer between locations.

SB236 — Extends the Covid-era rule that allows restaurants to sell to-go alcohol.

Hawaii

HB817 — Requires state agencies to purchase an increasing amount of locally grown food.

HB237 — Earmarks $350,000 to the department of agriculture for the mitigation and control of the two-lined spittlebug, which has damaged nearly 2,000-acres of pasture land.

SB263 — Establishes a “Hawaii Made” program and trademark, to promote Hawaiian-made products.

Idaho

HB51 — Amends existing law to provide nutrient management standards on dairy farms. Allows dairy farmers the option of using phosphorus nutrients.

HB232 — Changes the distribution of tax on high-alcohol-content beer from the state wine commission to the state hop growers commission, helping promote the craft industry.

Illinois

HB2620 — Allows small breweries, meaderies and winemakers to distribute their products to local bars, grocery stores and liquor stores directly rather than through a third party.

HB3490 — Amends Illinois Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act, which says, if a restaurant includes milk as a default beverage in a kid’s meal, the drink must be dairy milk and contain no more than 130 calories per container or serving.

HB3495 — The Brewers Economic Equity & Relief Act, allows for limited brewpub self-distribution, permanent delivery for small alcohol producers, direct-to-consumer shipping for in-state and out-of-state brewers and distillers and self-distribution for manufacturers producing more than one type of alcohol.

HR33 — Creates the Illinois Good Food Purchasing Policy Task Force to study the current procurement of food within the state and explore how Good Food Purchasing can be implemented to maximize the procurement of healthy foods that are sustainably, locally and equitably sourced.

HR46 — Urges the Illinois Department of Agriculture to study the effects and the types of land loss to Black farmers. Calls for state support and capacity building for Black farming communities across the state and a dedication to helping grow agriculture in rural, urban, and suburban areas.

HR117 — Urges the United States Department of Agriculture and the United States Department of Commerce to increase the exportation of Illinois dairy products to other nations.

SB2007 — The Home-to-Market Act, updates the state’s Illinois Cottage Food Law. Expands sales avenues for cottage food producers, allowing sales at fairs, festivals, home sales, pick-up, delivery and shipping (cottage food was previously only allowed to be sold at farmers markets).

Indiana

HB1396 — Updates many of Indiana’s outdated alcohol laws, some from the Prohibition Era. Amended various sections of Indiana’s alcohol code impacting permittees, trade regulation and other various definitions.

HB2773 — Allows bars, liquor stores and restaurants to permanently sell to-go alcohol orders, originally allowed temporarily during the Covid-19 pandemic.

SB144 — Allows bulk wine purchasing limits for farm wineries to apply only to wine sold directly to a consumer and not to wine sold through a wholesaler. Also allows the holder of an artisan distiller permit to also hold a distiller’s permit.

SB185 — Creates a working group made up of industry organizations, food safety experts, Indiana State Department of Health, Indiana State Board of Animal Health and Indiana State Department of Agriculture to submit recommendations to the state concerning home-based vendors and cottage food laws.

Iowa

HB384 — Updates rules regarding alcohol licenses. Lengthens the hours of sale for alcoholic beverages on Sunday.

HF766 — Allows home delivery of alcoholic beverages from bars and restaurants by third-party delivery services, such as Uber or DoorDash.

Kansas

HB2137 — Allows bars, liquor stores and restaurants to permanently sell to-go alcohol orders, originally allowed temporarily during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Kentucky

HR3 — Recognizes March 23 as Agricultural Day in the state.

HR19 — Recognizes June as Dairy Month, honoring the state’s dairy workers.

SB15 — Allows a microbrewery licensee to sell and deliver up to 2,500 barrels of product to any retail licensee and to set forth terms of contracts between microbrewers and distributors.

SB67 — Allows bars, liquor stores and restaurants to permanently sell to-go alcohol orders, originally allowed temporarily during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Louisiana

HB192 — Authorizes credit card payment to manufacturers and wholesale dealers of alcoholic beverages (when previously cash was only allowed).

HB219 — Allows the delivery of ready-to-drink alcohol beverages (sold in manufacturer sealed containers), allowing brewers with a brewing facility to self-distribute.

HB269 — Allows authorized state employees to destroy meat, seafood, poultry, vegetables, fruit or other perishable food of foreign origin which are subject of a current import ban from the federal government.

HB291 — Allows self-distribution to any brewer who operates a brewing facility in the state.

HB706 — Adds microwinery to microdistillery permits.

HR104 — Designates May 19, 2021, as Louisiana Craft Brewers’ Day in the state.

HR210 — Authorizes a state subcommittee to study and make recommendations to the government on the regulation of the growing craft brewing industry in the state.

Maine

SB133 — Clarifies that licensed Maine manufacturers of spirits, wine, malt liquor and low-alcohol spirits products may sell and ship their products to a person located in another state.

SB205 — Allows bars and restaurants to permanently sell to-go alcohol orders through take-out and delivery services if the liquor is accompanied by a food order. Also temporarily permits licensed Maine distilleries that operate tasting rooms but do not operate licensed on-premise retail to sell spirits through take-out and delivery services accompanied by a food order.

SB306 — Temporarily waives certain requirements for relicensing for restaurants that serve liquor to help food establishments during the Covid-19 pandemic.

SB307 — Allows all Maine alcohol manufacturers to sell directly to out-of-state consumers (current law only allows wine to be sold out-of-state).

SB479 — Amends definition of “low-alcohol spirits product” by raising the maximum alcohol level of a low-alcohol spirits product from 8% to 15%.

SB630 — Prohibits shelf-stable products from being sold as cider. Products that do not require refrigeration or are heat-treated cannot be labeled as cider.

SB636 — Establishes the Local Foods Fund, which helps schools purchase produce and other minimally processed foods from local farmers and producers.

SB822 — An act affirming that food seeds are a necessity in the state.

Maryland

HB185 — Prohibits an alcoholic beverages license holder from requiring that an individual buy more than one bottle, container or other serving of alcohol at a time.

HB264 — Requires entities that generate at least two tons of organic waste per week to arrange for disposal alternatives, like reduction, donation, animal feed or composting.

HB269 — Establishes the Urban Agriculture Grant Program in the Department of Agriculture to increase the viability of urban farming and improve access to urban-grown foods.

HB 555 — Repeals a prohibition on allowing drugstores to apply for a liquor license.

HB1232 — Codifies emergency orders to grant permanent to-go delivery of alcohol and online shipment privileges.

SB205 — Authorizes local alcoholic beverage licensing boards to temporarily allow restaurants and bars to sell to-go alcoholic beverages. Also requires Maryland’s Alcohol and Tobacco Commission and the Maryland Department of Health to study expanding alcohol access.

SB821 — Codifies the governor’s 2020 executive order to grant alcohol delivery and shipment. Also allows permitting to serve alcohol at off-premise, special events.

Fermentation in Anthropology

Fermented foods have had an impact on human evolution, and they continue to affect social dynamics, according to a new collection of 16 studies in the journal Current Anthropology. This research explores how “microbes are the unseen and often overlooked figures that have profoundly shaped human culture and influenced the course of human history.”

The journal’s special edition, Cultures of Fermentation, features work from multiple disciplines: microbiology, cultural anthropology, archaeology and biological anthropology. Researchers were based all over the globe.

“Humans have a deep and complex relationship with microbes, but until recently this history has remained largely inaccessible and mostly ignored within anthropology,” reads the introduction, Cultures of Fermentation: Living with Microbes. “Fermentation is at the core of food traditions around the world, and the study of fermentation crosscuts the social and natural sciences.”

The impetus for the articles was a 2019 symposium organized by the non-profit Wenner-Gren Foundation. This organization aims to bring together scholars to debate and discuss topics in anthropology.

“Fermentation is at the core of food traditions around the world, and the study of fermentation crosscuts the social and natural sciences,” the introduction continues. The aim of the symposium and corresponding research was to “foster interdisciplinary conversations integral to understanding human-microbial cultures. By bridging the fields of archaeology, cultural anthropology, biological anthropology, microbiology, and ecology, this symposium will cultivate an anthropology of fermentation.”

Here is a listing the included studies:

- Predigestion as an Evolutionary Impetus for Human Use of Fermented Food (Katherine R. Amato,Elizabeth K. Mallott, Paula D’Almeida Maia, and Maria Luisa Savo Sardaro). Using research on nonhuman primates, researchers conclude that “fermentation played a central role in enabling our earliest ancestors to survive in the forested grasslands in Africa where key anatomical features of our species emerged. Fermentation occurs spontaneously in nature. Most nonhuman primates cannot metabolize fermented products, but humans evolved the capacity to use them as fuel. …By breaking down tough and toxic plant species, fermentation helped humans meet the caloric requirements associated with their growing brains and shrinking guts. These anatomical changes both stemmed from and fueled the emergence of collective forms of know-how — microbial and human cultures fed on one another, in this view of the human past.”

- Toward a Global Ecology of Fermented Foods (Robert R. Dunn, John Wilson, Lauren M. Nichols, and Michael C. Gavin). This ecological view of fermentation maps the “emergence and divergence of the world’s many varieties of fermented foods.”

- Prehistoric Fermentation, Delayed-Return Economies, and the Adoption of Pottery Technology (Oliver E. Craig). Craig explores the central role of pottery in “people’s ability to amass the kinds of surpluses that allowed human communities to lay down roots.” Pots were ideal as the storage vessels that made it possible to domesticate microbes.

- Seeking Prehistoric Fermented Food in Japan and Korea (Shinya Shoda). This study focuses on fermentation’s rise in prehistoric Japan and Korea along with each country’s respective cultural achievements.

- Cultured Milk: Fermented Dairy Foods along the Southwest Asian–European Neolithic Trajectory (Eva Rosenstock, Julia Ebert, and Alisa Scheibner). Using archaeological evidence of fermentation, researchers track the “emergence of lactase persistence in sites where dairying made an early appearance. It appears that people ate cheese and yoghurt well before they drank milk: only a small subsection of the human population retains the enzymes needed to digest lactose into adulthood.”

- Missing Microbes and Other Gendered Microbiopolitics in Bovine Fermentation (Megan Tracy). Industrial dairy farms are finding “missing microbes” in cows, Tracy highlights in her study. Newborn calves are separated from their mothers in industrialized dairy farms, and thereby lose the critical gut connections that would have been made by drinking breast milk.

- Living Machines Go Wild: Policing the Imaginative Horizons of Synthetic Biology (Eben Kirksey). Kirksey profiles the International Genetically Engineered Machine competition in Boston, where living creatures made through genetic engineering tools are regarded as machines. “…life is being remade in novel and surprising ways as iGEM students use increasingly fast and cheap genetic engineering tools.”

- From Immunity to Collaboration: Microbes, Waste, and Antitoxic Politics (Amy Zhang). Research details “urban waste activists in China who are practicing a quiet form of resistance to the policies of the authoritarian state by using the fermentation of eco-enzymes to heal sickened rivers, bodies, and soils.”

- The Nectar of Life: Fermentation, Soil Health, and Bionativism in Indian Natural Farming (Daniel Münster). Münster delves into agricultural politics in India. He concludes that “fermentation’s effects are unpredictable: there is always more than one story to tell.”

- Microbial Antagonism in the Trentino Alps: Negotiating Spacetimes and Ownership through the Production of Raw Milk Cheese in Alpine High Mountain Summer Pastures (Roberta Raffaetà). Raffaetà investigates cheesemaking in the Italian alps, contrasting three different approaches — farmers who don’t use contemporary cheesemaking methods and only use microbes found in their terroir, , industrialized cheese producers,; and high-mountain farmers who mix cheesemaking elements from different times, such as using a standardized starter with local cultures.

- Protecting Perishable Values: Timescapes of Moving Fermented Foods across Oceans and International Borders (Heather Paxson). Raw milk cheese, cured meats and assorted ferments get their flavor from microbes. Paxson documents how transportation and distribution can erode the microbial content of these products, especially international imports. She concludes supply chains (especially international) should be further explored to make transporting products with live microbes viable.

- Enduring Cycles: Documenting Dairying in Mongolia and the Alps (Björn Reichhardt, Zoljargal Enkh-Amgalan,Christina Warinner, and Matthäus Rest). This research details the Dairy Cultures Ethnographic Database, an open resource featuring photos and videos of dairy production, landscapes and livestock in the Alps. Interviews, oral histories and folk songs are also included.

- Preserving the Microbial Commons: Intersections of Ancient DNA, Cheese Making, and Bioprospecting (Matthäus Rest). Rest traces the history and spread of dairying in Mongolia, Europe and the Near East. She concludes by calling on scientists and local producers to protect the “microbial commons” from “patenting and commodification.”

- Taste-Shaping-Natures: Making Novel Miso with Charismatic Microbes and New Nordic Fermenters in Copenhagen (Joshua Evans and Jamie Lorimer). This research for this paper took place at Noma in Copenhagen, and studied how fermentation allows the restaurant to tread a fine line “between ecologically responsible localism and the nativism associated with the rise of Denmark’s anti-immigrant right. Noma’s chefs have hit upon kōji, Japan’s “national fungus,” which they turn loose on Danish ingredients.”

- Bamboo Shoot in Our Blood: Fermenting Flavors and Identities in Northeast India (Dolly Kikon). Kikon explores fermented bamboo, a delicacy in India, and how it’s part of the local the community.

- Fermentation in Post-antibiotic Worlds: Tuning In to Sourdough Workshops in Finland (Salla Sariola). Sariola describes fermentation “as a politically progressive form of performance art.” She documents activities in China, where fermentation is used to “challenge the modernist regimes of purification that have turned microbes into the enemy. To learn to live better with microbes is to learn to live better with other kinds of difference — those associated with ethnicity, race, national origins, sexual orientation, ability, and age.”

- Published in Science

The São Jorge Cheese

On the remote, volcanic island of São Jorge in the middle of the Atlantic is what Insider calls “Portugal’s best-kept secret” — its eponymous cheese.

The weather conditions on the island make it perfect for cheesemaking, an art that began there 500 years ago. It’s humid, so cheese can rest at room temperature, packing the cheese with moisture. Cows (there are over 10,000 on the island, double the number of the human inhabitants) can graze year round.

São Jorge cheese is rich, with “hints of spiciness, and a grassy scent.” One of four dairy farmers on the island, João, ascribes the flavor to the cheesemaking process, which preserves “the flavors of the island in the cheese by not killing the native cultures that are present in the milk.” The milk is kept raw, unpasteurized and whey from the day before is used to ferment the milk instead of adding fermenting agents.

Read more (Insider)

- Published in Food & Flavor

How Can Brands Educate Consumers on Alt Protein?

Alternative protein companies need to stop advertising their brand as the most ethical choice and instead appeal to consumer’s taste buds.

“Sometimes plant-based food companies don’t really market themselves as food,” says Thomas Rossmeissl, head of global marketing for Eat Just, Inc., which develops plant-based “eggs” and cell-cultivated meat. “There’s this inclination to talk about mission. We say ‘We’re good for the planet,’ ‘It’s good for you,’ ‘It’s good for animals’ and obviously that’s all true and it’s admirable and it’s what drives me in our company. But it can come off like we’re sort of apologizing, that we’re negotiating with consumers, that a consumer is sacrificing something delicious to get something ethical or healthy.”

“People not buying (traditional)meat and cheese because an animal was killed or tortured. They buy because it tastes great.”

Irina Gerry concurs. Gerry is the chief marketing officer for Change Foods, an animal-free dairy brand that will launch their product in 2023. Alternative protein brands need to “flip the script from plant-based, rationalizing the food choices.” Brands need to help consumers feel that purchasing an alternative protein is a “natural choice rather than a sacrifice.”

The two spoke on a panel Insights on Consumer Perceptions of Alternative Proteins at the virtual Good Food Conference. The conference is put on by the Good Food Institute, an international nonprofit that promotes plant- and cell-based meat.

Wide Consumer Base Wanting Animal-Free

Animal-free is the main driver for customers to buy alternative products. The alternative protein industry is not just marketing to vegans, they’re also selling to flexitarians and omnivores concerned about welfare. Ninety-four percent of Eat Just consumers consume some type of animal protein.

“Sustainability is skyrocketing and potentially could cross over health as the main motivator, especially in the younger population,” Gerry says.

The modern American household family fridge is divided. There may be three types of eggs in there — conventional, cage-free and plant-based — and three types of milk — dairy milk, almond and oat. Consumers as young as 12 are the ones educating themselves on alternative proteins.

“We’re going to see this younger generation drive families to plant-based solutions,” Rossmeissl says.

Staying Honest, Maintaining Trust

Transparency will be central to public adoption. Laura Reiley, a reporter for The Washington Post who moderated the panel, noted “there hasn’t been tremendous transparency” with the alt protein market. She’s written about the market since its beginning and notes, because there’s intellectual property and so much research and development dollars, most companies have kept their food shrouded in mystery.

“We don’t want to sort of follow the example of the conventional industry. We can do better than that,” Rossmeissl says. “On the cultivated side, we have a huge responsibility to get this right. Not just as a company but as an industry, we can’t screw this up.”

Perceived unnaturalness by consumers of alt protein is a challenge. Using the term lab-grown “is disparaging to us as an industry” he continues, “but I think the best way we can address that is by being really honest and what’s in it and how it’s made.”

Gerry notes 90% of dairy cheese sold globally is made with non-animal remnants through precision fermentation — and that’s been the predominant way traditional cheese is made for over 20 years. It’s the same technology Change Food’s animal-free cheese uses.

“(These traditional cheeses) made through precision fermentation, they’re labeled under natural and oftentimes organic cheese products and nobody’s grown a third leg and nobody’s freaked out, right?” Gerry continues. “But now we’ve added one more element of that cheese — removing the cow from the cheese — and everybody seems to be greatly concerned.”

Chhurpi — Cheese from Chauri

Have you heard of chhurpi, the world’s hardest cheese? Developed thousands of years ago in a remote Himalayan village, it’s made from milk from a chauri (a cross between a male yak and a female cow) and is a favorite snack in pockets of eastern India, Nepal and Bhutan.

The protein-rich, low-fat cheese gets softer the longer it’s chewed — and people will chew on small cubes for hours. Chhurpi has low moisture content, making it edible for up to 20 years. It’s used in curries and soups or chewed as a snack (especially by yak herders during their long travels).

Chhurpi is fermented for 6-12 months, then stored in animal skin. It’s healthy and nutrient-rich, as chauri graze on herbs and grass in the high alpine mountains.

“It is said hard chhurpi takes anything between minutes to hours to soften, after which it tastes like a dense milky solid with a smoky flavour as it dissolves slowly. The so-called world’s hardest cheese is admittedly not everyone’s cup of tea, and I never could bite into one so far, but Nepalis across the country adore it,” writes BBC writer Neelima Vallangi.

Read more (BBC)

- Published in Food & Flavor

Managing Fermented Food Microbes to Control Quality

Fermented foods are produced through controlled microbial growth — but how do industry professionals manage those complex microorganisms? Three panelists, each with experience in a different field and at a different scale — restaurant chef, artisanal cheesemaker and commercial food producer — shared their insights during a TFA webinar, Managing Fermented Food Microbes to Control Quality.

“Producers of fermented foods rely on microbial communities or what we often call microbiomes, these collections of bacteria yeasts and sometimes even molds to make these delicious products that we all enjoy,” says Ben Wolfe, PhD, associate professor at Tufts University, who moderator the webinar along with Maria Marco, PhD, professor at University of California, Davis (both are TFA Advisory Board members).

Wolfe continued: “Fermenters use these microbial communities every day right, they’re working with them in crocks of kimchi and sauerkraut, they’re working with them in a vat of milk as it’s gone from milk to cheese, but yet most of these microbial communities are invisible. We’re relying on these communities that we rarely can actually see or know in great detail, and so it’s this really interesting challenge of how do you manage these invisible microbial communities to consistently make delicious fermented foods.”

Three panelists joined Wolfe and Marco: Cortney Burns (chef, author and current consultant at Blue Hill at Stone Barns in New York, a farmstead restaurant), Mateo Kehler (founder and cheesemaker at Jasper Hill in Vermont, a dairy farm and creamery) and Olivia Slaugh (quality assurance manager at wildbrine | wildcreamery in California, producers of fermented vegetables and plant-based dairy).

Fermentation mishaps are not the same for producers because “each kitchen is different, each processing facility, each packaging facility, you really have to tune in to what is happening and understand the nuance within a site,” Marco notes. “Informed trial and error” is important.

The three agreed that part of the joy of working in the culinary world is creating, and mistakes are part of that process.

“We have learned a lot over the years and never by doing anything right, we’ve learned everything we know by making mistakes,” says Kehler.

One season at Jasper Hill, aspergillus molds colonized on the rinds of hard cheeses, spoiling them. The cheesemakers discovered that there had been a problem early on as the rind developed. They corrected this issue by washing the cheese more aggressively and putting it immediately into the cellar.

“For the record, I’ve had so many things go wrong,” Burns says. A koji that failed because a heating sensor moved, ferments that turned soft because the air conditioning shut off or a water kefir that became too thick when the ferment time was off. “[Microbes are] alive, so it’s a constant conversation, it’s a relationship really that we’re having with each and every one on a different level, and some of these relationships fall to the wayside or we forget about them or they don’t get the attention they need.”

Burns continues: “All these little safeguards need to be put in place in order for us to have continual success with what we’re doing, but we always learn from it. We move the sensor, we drop the temperature, we leave things for a little bit longer. That’s how we end up manipulating them, it’s just creating an environment that we know they’re going to thrive in.”

Slaugh distinguishes between what she calls “intended microbiology” — the microbes that will benefit the food you’re creating — and “unintended microbiology” — packaging defects, spoilage organisms or a contamination event.

Slaugh says one of the benefits of working with ferments at a large scale at wildbrine is the cost of routine microbiological analysis is lower. But a mistake is stressful. She recounted a time when thousands of pounds of food needed to be thrown out because of a contaminant in packaging from an ice supplier.

“Despite the fact that the manufacturer was sending us a food-grade or in some cases a medical-grade ingredient, the container does not have the same level of sanitation, so you can’t really take these things for granted,” Slaugh says.

Her recommendations include supplier oversight, a quality assurance person that can track defects and sample the product throughout fermentation and a detailed process flow diagram. That document, Slaugh advises, should go far beyond what producers use to comply with government food regulations. It should include minutiae like what scissors are used to cut open ingredient bags and the process for employees to change their gloves.

“I think this is just an incredible time to be in fermented foods,” Kehler adds. “There’s this moment now where you have the arrival of technology. The way I described being a cheesemaker when I started making cheese almost 20 years ago was it was like being a god, except you’re blind and dumb. You’re unleashing these universes of life and then wiping them out and you couldn’t see them, you could see the impacts of your actions, but you may or may not have control. What’s happened since we started making cheese is now the technology has enabled us to actually see what’s happening. I think it’s this groundbreaking moment, we have the acceleration of knowledge. We’re living in this moment where we can start to understand the things that previously could only be intuited.”

- Published in Food & Flavor, Science

A New Breed of Animal-Free Milk

Can you imagine dairy-free milk without a nut or oat? An Israeli start-up is using precision fermentation to create animal-free milk “indistinguishable from the real thing.”

Imagindairy’s technology recreates the whey and casein proteins found in a mammal’s milk. The fermentation time is quick at 3-5 days, and the final product mimics the taste and texture of traditional dairy milk, without cholesterol or GMOs. The product is expected to be in stores in the next two years.

“Many food products are produced in fermentation, including enzymes, probiotics and proteins,” says Eyal Afergan, co-founder and CEO of Imagindairy. He emphasized how safe the product is. “In fact, on the contrary, fermentation process produces a cleaner product which is antibiotic free and reduces the exposure to a potential milk borne pathogens.”

Read more (Food Navigator)

Fermentation for Alternative Proteins

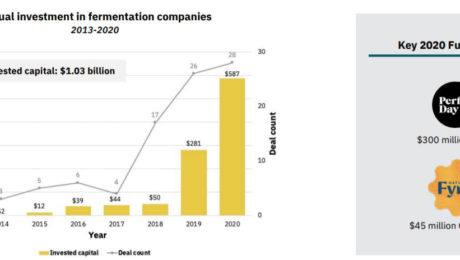

Investments in alternative protein hit their highest level in 2020: $3.1 billion, double the amount invested from 2010-2019. Over $1 billion of that was in fermentation-powered protein alternatives.

It’s a time of huge growth for the industry — the alternative protein market is projected to reach $290 billion by 2035 — but it represents only a tiny segment of the larger meat and dairy industries.

Approximately 350 million metric tons of meat are produced globally every year. For reference, that’s about 1 million Volkswagen Beetles of meat a day. Meat consumption is expected to increase to 500 million metric tons by 2050 — but alternative proteins are expected to account for just 1 million.

“The world has a very large demand for meat and that meat demand is expected to go up,” says Zak Weston, foodservice and supply chain manager for the Good Food Institute (GFI). Weston shared details on fermented alternative proteins during the GFI presentation The State of the Industry: Fermentation for Alternative Proteins. “We think the solution lies in creating alternatives that are competitive with animal-based meat and dairy.”

Why is Alternative Protein Growing?

Animal meat is environmentally inefficient. It requires significant resources, from the amount of agricultural land needed to raise animals, to the fertilizers, pesticides and hormones used for feed, to the carbon emissions from the animals.

Globally, 83% of agricultural land is used to produce animal-based meat, dairy or eggs. Two-thirds of the global supply of protein comes from traditional animal protein.

The caloric conversion ratios — the calories it takes to grow an animal versus the calories that the animal provides when consumed — is extremely unbalanced. It takes 8 calories in to get 1 calorie out of a chicken, 11 calories to get 1 calorie out of a pig and 34 calories to get 1 calorie out of a cow. Alternative protein sources, on the other hand, have an average of a 1:1 calorie conversion. It takes years to grow animals but only hours to grow microbes.

“This is the underlying weakness in the animal protein system that leads to a lot of the negative externalities that we focus on and really need to be solved as part of our protein system,” Weston says. “We have to ameliorate these effects, we have to find ways to mitigate these risks and avoid some of these negative externalities associated with the way in which we currently produce industrialized animal proteins.”

What are Fermented Alternative Proteins?

Alternative proteins are either plant-based and fermented using microbes or cultivated directly from animal cells. Fermented proteins are made using one of three production types: traditional fermentation, biomass fermentation or precision fermentation.

“Fermentation is something familiar to most of us, it’s been used for thousands and thousands of years across a wide variety of cultures for a wide variety of foods,” Weston says, citing foods like cheese, bread, beer, wine and kimchi. “That indeed is one of the benefits for this technology, it’s relatively familiar and well known to a lot of different consumers globally.”

- Traditional fermentation refers to the ancient practice of using microbes in food. To make protein alternatives, this process uses “live microorganisms to modulate and process plant-derived ingredients.” Examples are fermenting soybeans for tempeh or Miyoko’s Creamery using lactic acid bacteria to make cheese.

- Biomass fermentation involves growing naturally occurring, protein-dense, fast-growing organisms. Microorganisms like algae or fungi are often used. For example, Nature’s Fynd and Quorn …mycelium-based steak.

- Precision fermentation uses microbial hosts as “cell factories” to produce specific ingredients. It is a type of biology that allows DNA sequences from a mammal to create alternative proteins. Examples are the heme protein in an Impossible Foods’ burger or the whey protein in Perfect Day’s vegan dairy products.

Despite fermentation’s roots in ancient food processing traditions, using it to create alternative proteins is a relatively new activity. About 80% of the new companies in the fermented alternative protein space have formed since 2015. New startups have focused on precision fermentation (45%) and biomass fermentation (41%). Traditional fermentation accounts for a smaller piece of the category (14%). There were more than 260 investors in the category in 2020 alone.

“It’s really coming onto the radar for a lot of folks in the food and beverage industry and within the alternative protein industry in a very big way, particularly over the past couple of years,” Weston says. “This is an area that the industry is paying attention too. They’re starting to modify working some of its products that have traditionally maybe been focused on dairy animal-based dairy substrates to work with plant protein substrates.”

Can Alternative Protein Help the Food System?

Fermentation has been so appealing, he adds, because “it’s a mature technology that’s been proven at different scales. It’s maybe different microbes or different processes, but there’s a proof of concept that gives us a reason to think that that there’s a lot of hope for this to be a viable technology that makes economic sense.”

GFI predicts more companies will experiment with a hybrid approach to fermented alternative proteins, using different production methods.

Though plant-based is still the more popular alternative protein source, plant-based meat has some barriers that fermentation resolves. Plant-based meat products can be dry, lacking the juiciness of meat; the flavor can be bean-like and leave an unpleasant aftertaste; and the texture can be off, either too compact or too mushy.

Fermented alternative proteins, though, have been more successful at mimicking a meat-like texture and imparting a robust flavor profile. Weston says taste, price, accessibility and convenience all drive consumer behavior — and fermented alternative proteins deliver in these regards.

And, compared to animal meat, alternative proteins are customizable and easily controlled from start to finish. Though the category is still in its early days, Weston sees improvements coming quickly in nutritional profiles, sensory attributes, shelf life, food safety and price points coming quickly.

“What excites us about the category is that we’ve seen a very strong consumer response, in spite of the fact that this is a very novel category for a lot of consumers,” Weston says. “We are fundamentally reassembling meat and dairy products from the ground up.”

- Published in Business, Food & Flavor, Health, Science

What’s the Actual Probiotic Count of Commercial Kefir?

A new peer-reviewed study from researchers at the University of Illinois and Ohio State University found 66% of commercial kefir products overstated probiotic count and “contained species not included on the label.”

Kefir, widely consumed in Europe and the Middle East, is growing in popularity in the U.S. Researchers examined the bacterial content of five kefir brands. Their results, published in the Journal of Dairy Science, challenge the “probiotic punch” the labels claim.

“Our study shows better quality control of kefir products is required to demonstrate and understand their potential health benefits,” says Kelly Swanson, professor in human nutrition in the Department of Animal Sciences and the Division of Nutritional Sciences at the University of Illinois. “It is important for consumers to know the accurate contents of the fermented foods they consume.”

Probiotics in fermented products are listed in colony-forming units (CFUs). The more probiotics, the greater the health benefit.

According to a news release from the University of Illinois: “Most companies guarantee minimum counts of at least a billion bacteria per gram, with many claiming up to 10 or 100 billion. Because food-fermenting microorganisms have a long history of use, are non-pathogenic, and do not produce harmful substances, they are considered ‘Generally Recognized As Safe’ (GRAS) by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and require no further approvals for use. That means companies are free to make claims about bacteria count with little regulation or oversight.”

To perform the study, the researchers bought two bottles of each of five major kefir brands. Bottles were brought to the lab where bacterial cells were counted and bacterial species identified. Only one of the brands studied had the amount of probiotics listed on its label.

“Just like probiotics, the health benefits of kefirs and other fermented foods will largely be dependent on the type and density of microorganisms present,” Swanson says. “With trillions of bacteria already inhabiting the gut, billions are usually necessary for health promotion. These product shortcomings in regard to bacterial counts will most certainly reduce their likelihood of providing benefits.”

The news release continues:

When the research team compared the bacteria in their samples against the ones listed on the label, there were distinct discrepancies. Some species were missing altogether, while others were present but unlisted. All five products contained, but didn’t list, Streptococcus salivarius. And four out of five contained Lactobacillus paracasei.

Both species are common starter strains in the production of yogurts and other fermented foods. Because those bacteria are relatively safe and may contribute to the health benefits of fermented foods, Swanson says it’s not clear why they aren’t listed on the labels.

Although the study only tested five products, Swanson suggests the results are emblematic of a larger issue in the fermented foods market.

“Even though fermented foods and beverages have been important components of the human food supply for thousands of years, few well-designed studies on their composition and health benefits have been conducted outside of yogurt. Our results underscore just how important it is to study these products,” he says. “And given the absence of regulatory scrutiny, consumers should be wary and demand better-quality commercial fermented foods.”

Q&A: Sophie Burov, Secret Lands Farm

When Sophie and Alexander Burov moved to Toronto, Canada, from Moscow, Russia, in 2007, farming wasn’t on their radar. Both entrepreneurs — she in fashion, he in mining — they were accustomed to life in one of the biggest cities in the world, not to rural farming. And their knowledge of fermented dairy was limited to taste — Alexander loved the tangy kefir he’d been drinking since childhood; Sophie devoured cheese and yogurt.

Sophie was a sheep’s milk aficionado, having tried it years earlier, She had fallen in love with its flavor, but soon learned how hard it was to find fresh sheep’s milk, especially in her native Russia. So when she met a producer at a farmer’s market in Canada, Sophie felt inspired to make her own sheep’s milk products.

“At that moment, I couldn’t even imagine running a farm,” Sophie says. She volunteered at a local dairy and sheep farm, quickly learning that: “Business is business and farming is business too, but it’s love as well. Farming is a lot of love.”

Today, Sophie, Alexander and their son Roman run the 150-acre Secret Lands Farms, south of Owen Sound in Ontario, Canada. Utilizing old-world European farming traditions, they produce a range of artisanal sheep’s milk dairy products at their on-site creamery: kefir, two varieties of yogurt, and 25 cheeses. Their kefir — made from centuries-old Tibetian grains — is also the base for their cheeses. Secret Lands is the only producer in Canada (and one of few in North America) using kefir grains as a culture for cheese.

“Seeing is believing — but tasting is falling in love,” Sophie says. “When you taste our product, you can feel the love.”

Sophie recently spoke with TFA; below are highlights from the interview.

The Fermentation Association: You purchased the farm seven years ago. Farming is hard work! Tell me what made you decide to purchase a farm?

Sophie Burov: Yes, we purchased it in 2013. The idea came about eight years ago. You know sometimes when you reach a point when you need to reconsider the purpose of your life and what you’re doing, why you’re doing it, what’s the purpose of your existing?

The agricultural sector is huge in Canada but not dairy sheep farming , so I started thinking about it as a hobby farm and we’d still live in the city, but it turned in a different direction because if you want just a hobby, it will only be your hobby. If you want something serious, your life and dedication is different when it’s your life. I believe it’s from guidance from God, I was praying a lot.

Looking back, this is the hardest job me and my husband have ever done. But it’s rewarding mentally. I believe in the spirit of the land and the animals and what you’re doing through the product you give to people, you become a bridge connection between the land and the people. Through the product, you can tell much more than through words.

If you want to go farming for money and there’s no love between you and the animals, forget it. There has to be love between you and the animals. Everyday they are teaching us how to be better human beings because sheep are very social. They are also very appreciative animals. They give back their love. If they’re struggling, you’re struggling with them.

We were very, very lucky, because we found the first sheep dairy farmers and breeders in North America — Axel Meister and his wife, Chris Buschbeck [owner of WoolDrift Farm in Markdale, Grey County, Ontario]. They brought this flock from Germany in the middle of the ‘80s and they started developing this flock in the middle of North America. When we decided to do this farm, we met Axel and started going to his farm and volunteering and he was guiding us, telling us what books to read and what to pay attention to with the sheep. His wife Chris is a vet for sheep and she helps us with our sheep.

TFA: How long did it take you to become experts at sheep farming?

SB: We are still learning. The first three years were extremely, extremely difficult. It was a hard time because, working as a volunteer at these different farms, it was very different compared to doing it yourself because all the ups, they’re yours, and all the downs, they’re yours.

TFA: Where do you sell your products?

SB: We sell at the farmers market on Saturday and home delivery twice a week. I believe home delivery is another bridge between the customers and us. If they have questions, we’re always here to answer. It’s not the easiest way to do it, but I believe that for small farmers and small producers, it’s the best way to connect with your customers and make money. We tried to work with retail stores, but retail chains, they are squeezing you. There’s no money for small farms. You can increase your flock, your production, to make more money, but we do not wish to become huge. For now it’s an ideal model for us to sell through online sales to all of the Canadanian provinces

TFA: What is a typical day like at the farm?

SB: Everyday is different. From the beginning, we were working like slaves. It was very unhealthy, all of us were sleeping just an hour, working at the farm then driving to the farmers market. Sometimes our working time was 22 hours a day, it was killing us. But now it’s easier because we have people who can help us in production and my husband Alex has people helping him on the farm, so it’s a little easier. [Secret Lands has anywhere from 8-10 employees, depending on the season].

The most difficult period of the year is lambing season. My husband and son are not sleeping at all. They have naps, but then they’re back to the barn. We do lambing once a year for a few months in spring. We do not do artificial insemination, we do it the way nature intended. The sheep are pasture-raised, grass-fed and no hormones.

TFA: You are Russian natives, where kefir originates from. Did you have kefir before starting the farm?

SB: Yes, kefir started in Russia, it began end of the 19th Century. It came from the Caucasus Mountains. But to be honest, when I started thinking about farming and a sheep dairy farm, I didnt even think about kefir, I was thinking about just yogurt because at that moment I was a yogurt and cheese person. I have hated kefir since I was a kid. My husband has been loving it since he was born.

But when we met our sheep breeder, at that moment he gave me a glass of kefir at his farm. He was just producing kefir for himself, I tried it and thought this was interesting. He gave me a handful of kefir grains, and I made kefir and brought it to our church community for people to try and share with people our idea of what we would be doing on the farm. One lady started asking me so many questions about kefir. And I realized my knowledge about kefir is null. I went back home and started my research and I was just shocked. It was so amazing, it was my ah-ha moment. Kefir is incomparable with yogurt in nutrition. Then my amazement was doubled, tripled, because sheep’s milk kefir, the product is different, the amount of calcium is much higher than cow’s or goat’s milk. In the kefir variation, our body will assimilate twice the calcium and protein.

The real kefir — made from kefir grains — it’s very limited on the market because it’s difficult to make. Seven years ago I had a handful of kefir grains, but now I can produce nine pails of 15 liters each of kefir at the same time. It’s not a huge amount actually if we compare it to someone who does it commercially. It’s impossible to make money with that amount of product. When people ask why our product is high priced, I tell them because it’s the real stuff.

TFA: Tell me some of the benefits of sheep’s milk kefir.

SB: It’s a natural probiotic, it’s the most natural probiotic in the whole world. Some scientists are saying it has 50 different variations of probiotics.

If you are taking pills or taking kefir from commercial cultures, you are not digesting the good bacteria. But if you take the real kefir, it’s becoming you and it works. People ask “Why am I supposed to drink it all the time? What’s the reason?” I tell them even the best troops in the whole world can do a lot, but if you are not feeding them, they become weak. These troops are fighting the bacteria in your body and they’re fighting nonstop, invisibly fighting bad bacteria in your body. People need to understand there’s no miracle. You can’t drink a glass or a liter and that’s all. You need to do it constantly and it will give you the health benefits from the nutrients and vitamins. I drink half a glass for my breakfast and and half a glass at night.

In kefir, your body assimilates the nutrients and vitamins. Sheep’s milk is easier to digest because it’s closest to mother’s milk, more than goat or cow milk — it’s a superior milk. You can even freeze this milk, we freeze it for the winter time and when you defrost it, it doesnt change the structure. The globule of the fat in sheeps milk is four times smaller than cow’s milk. It’s easiest to digest for people, especially with lactose issues. Same with our cheese made from kefir, it has the same benefits.

TFA: What about your other fermented products? Tell me about the baked milk yogurt.

SB: The baked milk yogurt can be confusing to people because they say “Doesn’t it kill all the probiotics in your yogurt?” No, we are slow cooking it, and then we add cultures. It is Russian and Ukrainian, this process of making yogurt. It goes back to history when people in villages were baking bread in a wooden oven. It was always pre-heated, they would put milk in a cast iron pot or clay pot. It would stay there overnight, and the water is evaporating and the milk sugar is caramelizing. We call it the healthiest creme brulee. It has the taste of caramel, but no sugar or caramel added because of the process of the caramelization of the lactose.

TFA: You make traditional yogurt, too?

SB: Yes, we are working with cultures from Italy. I tried to work with what’s available here, but it gave me a really sour, tart taste. It was too genetically modified, and that genetically modified culture is not allowed in Europe. We’re bringing all our cultures for our yogurt from Europe.

TFA: Tell me more about your cheeses.

SB: We do different varieties of cheeses called kefir cheese, we use zero commercial cultures. We are using only kefir. It takes more time, it changes a little bit of the taste for the cheese, but it’s the same culture. We’re able to produce fresh cheese to a few-years-old Pecorino. But it’s the same culture.

David Archer, he wrote The Art of the Natural Cheesemaker, I met him just before we started making kefir cheese. At that moment, his book had just released and people introduced us at the farmers market. He came to our farm and we spent a month together in our small-size commercial kitchen and creamery and he helped convert everything to kefir cheeses.

I’m always asking people just think about the history of the cheesemaking, cheesemakers they didn’t use the cultures from the lab, it was a natural fermentation. It was the same farm with the same bacteria, they’ve been doing different varieties of cheese, but it depends on your region because the environment is different. Sometimes, you don’t know what’s involved because the weather is different, the humidity is different and even our mood is different. If you’re not in a good mood, it comes out in the cheese.

Same with kefir cheese, we’re using the same kefir as a culture for our milk, and it gives us different results. Even with our soft-ripened cheeses, Camembert and Brie, the rind we are growing, it does not have any artificial bacteria that people put on top of the cheese to grow a rind. Kefir gives this ability to grow the rind naturally. But you need to be thoughtful and it involves a lot of labor because you need to keep your eye on the cheese everyday to see what’s growing on top. And you need to develop the right bacteria for the rind of the cheese.

TFA: Is the process to make a kefir cheese different from a traditional cheese?

SB: A little bit, but now much. The process to make it takes more time than traditional cheesemaking because you need to add kefir and wait. But it’s worth it because it’s a superior food that brings you all the good protein. It’s easier to digest compared to even meat because it’s naturally fermented.

TFA: How long did it take you to perfect these recipes?

SB: It’s an ongoing process. From the beginning I didn’t plan to do 25 cheeses. But I was surprised, people started asking me at the farmers market if I would make hard cheese. Now Pecorino is our top seller and our main product, it’s a sheep’s milk cheese made of full-fat, whole sheep’s milk.

Sometimes people are suspicious — “Oh a Russian, doing Pecorino in Canada?” But when they taste it, they love it.

Even as small producers, we are like big producers, because we are doing a big range of products. We have four more cheeses planned for the future. The sheep’s milk gouda is in the aging room now.

TFA: How does the taste of a fermented sheep’s milk product taste compared to fermented goat or cow dairy?

SB: Sheep’s milk is very sweet and high in fat, but good fat. It’s very smooth and creamy. My first impression when I tried a glass of sheep’s milk, it was like I was drinking the best cow’s cream of my life. It’s rich, but not heavy because the globule of the fat is very small. It gives richness, but at the same time, lightness. It’s so full of the different nodes of the taste. It’s sweet but not overly sweet, it’s balanced. The quality of the milk affects all the range of the products that we do.

Sheep milk is a very good balance between rich and light.This taste goes through the product. It’s totally different from goat milk, it doesn’t have a strong taste. Many people don’t like the taste of goat milk, the smell and taste. Sheep doesn’t have that strong taste at all.

TFA: I love that you are very invested in the welfare of your animals.

SB: For me the most important, I care how people are treating the animals. If the animals are healthy, free-range, pasture-raised, people are taking good care of them, they’re not giving them chemical-produced silo. We’re giving our animals fermented hay because it’s easier to digest. Year-round, our animals are grass-fed. We are not just farmstead producers, we are much more. Our main concern is the health of our soil. The quality of the product, the health of the product, it starts from the health of our lamb. Only good soil can guarantee good health for your animals.

TFA: Where do you see the future of fermented products?

SB: I believe in the future of fermentation. However, it’s not easy. For example, back in Russia, back in Europe, my family we’ve been doing sauerkraut since I can remember. Even here in Canada, living in downtown Toronto, even when we were in a condo, I was making sauerkraut. And kombucha.

But people are losing that connection to their food. They need the right guidance to reconsider their eating habits. I believe it will take some time to change, but we are optimistic.

- Published in Business, Food & Flavor