Sake Brewers Suffer in Japan

As Covid-19 restrictions are lifted, American sake breweries are opening their doors to customers again. But across the world in Japan, where sake originated, many izakaya or sake pubs remain closed. Japanese brewers expect sales to slump for a second year in a row because of the pandemic.

“This right now might be the most challenging time for the industry,” says Yuichiro Tanaka, president of Rihaku Sake Brewing. “There’s nothing much we can do about that. In our company, we’re trying to become more efficient and streamline our processes so that once the world economy returns to what it formerly was, we’ll be able to much more efficiently fill orders.”

Tanaka, Miho Imada (president and head brewer of Imada Sake Brewing) and Brian Polen (co-founder and president of Brooklyn Kura) spoke in an online panel discussion Brewers Share Their Insider Stories, part of the Japan Society’s annual sake event. John Gauntner, a sake expert and educator, moderated the discussion and translated for Tanaka and Imada, who both gave their remarks in Japanese. (Pictured from left to right: Gautner, Tanaka, Imada and Polen.)

Recovery Struggles

Japan — which has been slow to vaccinate (only 9% of the population has been fully vaccinated, compared to 47% in the United States) — is currently in a third state of emergency. In the country’s large cities, no alcohol can be served in restaurants. “This is just devastating to the industry,” says Gaunter.

Though sake pubs in smaller metropolitan areas and countryside regions are allowed to be open, few people are out drinking. Many pubs have closed, and others refuse entry to anyone from outside of their prefecture.

“Sales of sake are very seriously affected,” says Imada, one of few female tôji or master brewers. “Rice farmers that grow sake rice are seriously affected as well. If brewers can’t sell sake, they have no empty tanks in which to make sake, so they don’t order any rice and the effects are transmitted down to rice farmers.”

Sake rice is more challenging to grow than table rice because the rice grains must be longer. The amount of sake rice planted in Hiroshima — where Imada Sake Brewing is based — is down 30-40%. Farmers may give up growing sake rice and switch to table rice for good.

The effects of Covid-19 on Japan’s sake brewers will linger into the fall when the next brewing season starts again.

“We cannot really expect a recovery in the amount of sake produced next season, and so therefore production will drop for two years in a row,” she says.

Premium sake brewers with rich generational historys — like Imada Sake Brewing and Rihaku Sake Brewing — are struggling to sell their high-end products.. Department store in-store tastings — a boon to premium sake brewers — have disappeared.

Adapting to Covid

In New York, as pandemic recovery efforts continue, Polen has seen the pent-up demand from consumers. Brooklyn Kura’s retail, on-premise and taproom sales are increasing. After scaling back production and their team in 2020, Brooklyn Kura is now hiring again.

“More importantly, and I think the silver lining out of this, we really needed to redouble our efforts to create a direct line of communication with our best customers,” Polen says.

During the pandemic, Brooklyn Kura launched both a direct-to-consumer business and a subscription service featuring limited-run sakes. “That’s helped us on our road to recovery.”

Imada Sake, too, found ways to improve business. They’re selling bottles and hosting tasting events through their website.

“One of the principles of the Hiroshima Tôji Guild [guild of master sake brewers], the expression is ‘Try 100 things and try them 1,000 times.’ Or in other words the point is keep trying new things and see what contributes towards improvement,” Imada says. “These words convey the spirit of using skill and technique or technology to get beyond difficulties.”

Imada Sake exports 20% of its production; as more countries recover, exports continue to grow. Direct-to-consumer sales, she says, vary and are only constant around Christmas.

Rihaku Sake sells much of their sake to distributors and is seeing international exports increase. They also began direct-to-consumer internet sales, but that channel “didn’t grow as much as I was hoping.”

Consumer Education

France and Italy export billions of dollars of wine a year. Polen argues that sake could be an equally profitable export for Japan. Education and exposure, he says, are the challenge.

“In craft beer and fine wine, a lot of those initial encounters with those products come in places like the tap room in Brooklyn or the wineries in California or the local craft brewery, so creating more of those connection points and initial introduction points in a market like the U.S., having a better facility to distribute sake across the U.S., will help to expand the market, not just to domestic producers but also for the storied producers of Japan as well,” Polen says.

Sake is the national beverage of Japan, and strict brewing laws strive to keep it pure. Japanese sake can only be made with koji and steamed rice. Add hops to it and the drink cannot be called sake legally anymore.

Many sake tôji in Japan are running a multi-generational family brewery.“These craftsmen, who have been brewing sake since they were young, have decades of experience to develop what we call keiken to chokkan or experience and intuition,” Tanaka says, adding that Japan is the only place to buy certain industrial-sized sake making machines such as steamers and pressers. “There’s a lot of advantages that breweries in Japan have. If brewers overseas get too good, this might actually cause problems for brewers in Japan. However, more important than that, I think it’s important for all of us to continue to study how to make better and better sake so everyone around the world can enjoy it.”

Rihaku tries to make their sake recognizable to local consumers who are unfamiliar with the rice wine. Their Junmai Ginjo sake has the nickname “Wandering Poet,” a reference to the famous poet Li Po. Legend says Li Po drank a bottle of sake then wrote 1,000 poems.

“We think a lot about how to get more people that are non-Japanese and outside of the Japanese context excited about sake making and excited about the sake we make,” Polen says. “That includes those folks that are passionate fermenters, like the beer community, that really want to know and learn about things like spontaneous fermentation. So (sake) styles, like yamahai and kimoto, are very easy transition points, very easy talking points for us with that community of brewers and consumers that are really excited to drill deeper into fermentation, especially natural fermentation.”

- Published in Business

Fermentation for Alternative Proteins

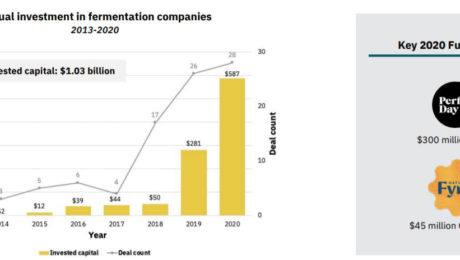

Investments in alternative protein hit their highest level in 2020: $3.1 billion, double the amount invested from 2010-2019. Over $1 billion of that was in fermentation-powered protein alternatives.

It’s a time of huge growth for the industry — the alternative protein market is projected to reach $290 billion by 2035 — but it represents only a tiny segment of the larger meat and dairy industries.

Approximately 350 million metric tons of meat are produced globally every year. For reference, that’s about 1 million Volkswagen Beetles of meat a day. Meat consumption is expected to increase to 500 million metric tons by 2050 — but alternative proteins are expected to account for just 1 million.

“The world has a very large demand for meat and that meat demand is expected to go up,” says Zak Weston, foodservice and supply chain manager for the Good Food Institute (GFI). Weston shared details on fermented alternative proteins during the GFI presentation The State of the Industry: Fermentation for Alternative Proteins. “We think the solution lies in creating alternatives that are competitive with animal-based meat and dairy.”

Why is Alternative Protein Growing?

Animal meat is environmentally inefficient. It requires significant resources, from the amount of agricultural land needed to raise animals, to the fertilizers, pesticides and hormones used for feed, to the carbon emissions from the animals.

Globally, 83% of agricultural land is used to produce animal-based meat, dairy or eggs. Two-thirds of the global supply of protein comes from traditional animal protein.

The caloric conversion ratios — the calories it takes to grow an animal versus the calories that the animal provides when consumed — is extremely unbalanced. It takes 8 calories in to get 1 calorie out of a chicken, 11 calories to get 1 calorie out of a pig and 34 calories to get 1 calorie out of a cow. Alternative protein sources, on the other hand, have an average of a 1:1 calorie conversion. It takes years to grow animals but only hours to grow microbes.

“This is the underlying weakness in the animal protein system that leads to a lot of the negative externalities that we focus on and really need to be solved as part of our protein system,” Weston says. “We have to ameliorate these effects, we have to find ways to mitigate these risks and avoid some of these negative externalities associated with the way in which we currently produce industrialized animal proteins.”

What are Fermented Alternative Proteins?

Alternative proteins are either plant-based and fermented using microbes or cultivated directly from animal cells. Fermented proteins are made using one of three production types: traditional fermentation, biomass fermentation or precision fermentation.

“Fermentation is something familiar to most of us, it’s been used for thousands and thousands of years across a wide variety of cultures for a wide variety of foods,” Weston says, citing foods like cheese, bread, beer, wine and kimchi. “That indeed is one of the benefits for this technology, it’s relatively familiar and well known to a lot of different consumers globally.”

- Traditional fermentation refers to the ancient practice of using microbes in food. To make protein alternatives, this process uses “live microorganisms to modulate and process plant-derived ingredients.” Examples are fermenting soybeans for tempeh or Miyoko’s Creamery using lactic acid bacteria to make cheese.

- Biomass fermentation involves growing naturally occurring, protein-dense, fast-growing organisms. Microorganisms like algae or fungi are often used. For example, Nature’s Fynd and Quorn …mycelium-based steak.

- Precision fermentation uses microbial hosts as “cell factories” to produce specific ingredients. It is a type of biology that allows DNA sequences from a mammal to create alternative proteins. Examples are the heme protein in an Impossible Foods’ burger or the whey protein in Perfect Day’s vegan dairy products.

Despite fermentation’s roots in ancient food processing traditions, using it to create alternative proteins is a relatively new activity. About 80% of the new companies in the fermented alternative protein space have formed since 2015. New startups have focused on precision fermentation (45%) and biomass fermentation (41%). Traditional fermentation accounts for a smaller piece of the category (14%). There were more than 260 investors in the category in 2020 alone.

“It’s really coming onto the radar for a lot of folks in the food and beverage industry and within the alternative protein industry in a very big way, particularly over the past couple of years,” Weston says. “This is an area that the industry is paying attention too. They’re starting to modify working some of its products that have traditionally maybe been focused on dairy animal-based dairy substrates to work with plant protein substrates.”

Can Alternative Protein Help the Food System?

Fermentation has been so appealing, he adds, because “it’s a mature technology that’s been proven at different scales. It’s maybe different microbes or different processes, but there’s a proof of concept that gives us a reason to think that that there’s a lot of hope for this to be a viable technology that makes economic sense.”

GFI predicts more companies will experiment with a hybrid approach to fermented alternative proteins, using different production methods.

Though plant-based is still the more popular alternative protein source, plant-based meat has some barriers that fermentation resolves. Plant-based meat products can be dry, lacking the juiciness of meat; the flavor can be bean-like and leave an unpleasant aftertaste; and the texture can be off, either too compact or too mushy.

Fermented alternative proteins, though, have been more successful at mimicking a meat-like texture and imparting a robust flavor profile. Weston says taste, price, accessibility and convenience all drive consumer behavior — and fermented alternative proteins deliver in these regards.

And, compared to animal meat, alternative proteins are customizable and easily controlled from start to finish. Though the category is still in its early days, Weston sees improvements coming quickly in nutritional profiles, sensory attributes, shelf life, food safety and price points coming quickly.

“What excites us about the category is that we’ve seen a very strong consumer response, in spite of the fact that this is a very novel category for a lot of consumers,” Weston says. “We are fundamentally reassembling meat and dairy products from the ground up.”

- Published in Business, Food & Flavor, Health, Science

Measuring and Monitoring Fermented Food Microbiomes

Analyzing the microbiome of a fermented food will help manage product quality and identify the microbes that make up the microscopic life. Though diagnostic techniques are still developing, they’re getting cheaper and faster.

“Why should we measure the microbial composition of fermented foods? If you can make a great batch of kimchi or make awesome sourdough bread, who cares what microbes are there,” says Ben Wolfe, PhD, associate professor at Tufts University. “But when things go bad, which they do sometimes when you’re making a fermented food, having that microbial knowledge is essential so you can figure out if a microbe is the cause.”

Wolfe and Maria Marco, PhD, professor at University of California, Davis, presented on Measuring and Monitoring Fermented Food Microbiomes during a TFA webinar. Both are members of the TFA Advisory Board. During the joint presentation, the two gave an overview on microbiome analysis techniques, such as culture-dependent and culture-independent approaches.

Measuring Microbial Composition

Wolfe says there are three reasons to measure the microbial composition of fermented foods: baseline knowledge, quality control and labelling details.

“Just telling you what is in that microbial black box that’s in your fermented food that can maybe be really useful for thinking about how you could potentially manipulate that system in the future,” he says.

What can you measure in a fermented food? First there’s structure, which can determine the number of species, abundance of microbes and the different types. And second is function, which can suggest how the food will taste, gauge how quickly it will acidify and help identify known quality issues.

Studying these microorganisms — unseen by the naked eye — is done most successfully through plating in petri dishes. This technique was developed in the late 1800s

“This allowed us to study microorganisms at a single cell level to grow them in the laboratory and to really begin to understand them in depth,” Marco says. “This culture-based method, it remains the gold standard in microbiology today.”

However, there’s been a “plating bias since the development of the petri dish,” she says. Science has focused on only a select few microbes, “giving us a very narrow view of microbial life.” Fewer than 1% of all microbes on earth are known.

The microbes in fermented foods and pathogens have been studied extensively.“Over these 150 years we have now a much better understanding of the processes needed to make fermented foods, not just which microbes are these but what is their metabolism and how does that metabolism change the food to give the specific sensory safety health properties of the final product,” she says

Marco and Wolfe both shared applications of these testing techniques from research at their respective universities.

Application: Olives

At UC Davis, Marco and her colleagues studied fermented olives. Using culture-based methods, they found that the microbial populations in the olives change over time. When the fruits are first submerged for fermentation, there’s a low number of lactic acid bacteria on them — but within 15 days, these microbes bloom to 10-100 million cells per gram.

Marco was called back to the same olive plant in 2008 because of a massive spoilage event. The olives smelled and tasted the same, but had lost their firmness.

Using a culture-independent method to further study what microbes were on the defective olives, she discovered a different microbiota than on normal ones, with more bacteria and yeast.

The culprit was a yeast.“Fermented food spoilage caused by yeast is difficult to prevent,” Marco says. “New approaches are needed.”

Application: Sourdough

At Tufts, Wolfe was one of the leaders on a team of scientists from four different universities that studied 500 sourdough starters with an aim to determine microbial diversity. Starters from four continents were examined in the first sourdough study encompassing a large geographic region.

The research team identified a large diversity among the starters, attributed to acetic acid bacteria. They also found geography doesn’t influence sourdough flavor.

“Everyone talks about how San Francisco sourdough is the best, which it is really great, but in our study we found no evidence that that’s driven by some special community of microbes in San Francisco,” Wolfe said. “You can find the exact same sourdough biodiversity based on our microbiome sequencing in San Francisco that you can find here in Boston or you could find in France or in any part of the world, really.”

Wolfe and Marco will return for another TFA webinar on July 14, Managing Microbiomes to Control Quality.

- Published in Science

Fermented Skincare?

Is the future of skincare products fermented? A Finnish company is tapping into consumer trends they believe “will become the norm in five to ten years.” Brand Circulove is natural, sustainable, holistic — and made with fermented ingredients. Ingredients are fermented for 3-5 weeks, then food-grade oils are added.

“It’s an old tradition built in[to] this new technology,” says Paivi Paltola, Circulove CEO and co-founder. “It’s also this kind of more holistic way of thinking because fermentation helps your skin renew itself.”

Paltola says consumers are familiar with fermented ingredients in foods and beverages, but more education is needed to help them understand their role in beauty and skincare products.

Read more (Cosmetics Design)

- Published in Business

Supplements vs. Fermented Foods

Two UCLA professors of medicine encourage people “rather than thinking in terms of supplements, add some fermented foods to your diet.” In a Q&A, the doctors say the popularity of probiotics, postbiotics and the gut microbiome has blurred their value, despite the plethora of reputable scientific research. Product manufacturers — as has happened before, with terms like “gluten-free” — have begun labelling everything as containing -biotics or benefitting the gut microbiome.

“The word probiotics refers to the beneficial microbes found in certain fermented foods and beverages, as well [as] in specially formulated nutritional supplements,” write UCLA doctors Eve Glazier and Elizabeth Ko. “That means that any fermented food that contains or was made by live bacteria contains postbiotics. … Initial findings suggest that postbiotics may play a role in maintaining a balanced and robust immune system, support digestive health and help to manage the health of the gut microbiome.”

Read more (Journal Review)

- Published in Science

Pandemic Bakes New Bread Business

Sourdough was the “breakout star of pandemic-era kitchens,” so it’s no surprise that sourdough hobbyists are turning their newly-found craft into a profession. There’s a new wave of bakers obtaining Cottage Food Operations licenses so they can sell their homemade bread. Max Kumangai (pictured), an unemployed Broadway actor, was one of many who started a bread-baking business during the pandemic.

“It’s a really exciting time,” says Mitch Stamm, executive director of the Bread Bakers Guild of America. “Many small bakeries — one-person bakeries, two-person bakeries — they are doing beautifully.” The Guild says recessions have historically fueled passion in cooking and baking. Home bakers are finding their new quarantine hobby is a passionate career move, allowing them to create delicious food and socialize with customers.

“For sure there was a feeling, ‘I hate my job, I hate my life, I’m going to wake up and follow my heart,’” says Penny Stankiewicz, a pastry and baking arts instructor at the Institute of Culinary Education. That school received 85% more applications in 2020 compared to 2019.

Read more (The New York Times)

- Published in Business

Kefir Brands Respond

The kefir brands recently tested for their probiotic claims are challenging the results.

In May, a study found 66% of commercial kefir products overstated probiotic counts and “contained species not included on the label.” The Journal of Dairy Science Communications published the peer-reviewed work by researchers at the University of Illinois and Ohio State University.

“Based on the results…there should be more regulatory oversight on label accuracy for commercial kefir products to reduce the number of claims that can be misleading to consumers,” reads the study. “Classification as a ‘cultured milk product’ by the FDA requires disclosure of added microorganisms, yet regulation of ingredient quality and viability need to be better scrutinized. All 5 kefir products guaranteed specific bacterial species used in fermentation, yet no product matched its labeling completely.”

Researchers tested two bottles of each of five major kefir brands: Maple Hill Plain Kefir, Siggi’s Plain Filmjölk, Redwood Hill Farm Plain Goat Milk Kefir, CoYo Kefir and Lifeway Original Kefir. Bottles were measured for microbial count and taxonomy to validate label claims.

The Fermentation Association reached out to the five brands involved and asked for their responses to the results. Redwood Hill and Lifeway both submitted detailed statements. Maple Hill, Siggi’s and CoYo did not return multiple requests for comment.

Probiotic Count

Probiotics in fermented products are listed in colony-forming units (CFUs), and the study found kefir from both Lifeway and Redwood Hill contained fewer CFUs than what was claimed on the label. But these brands — who send their products to third-party labs for testing — said the results are not accurate.

Lifeway refutes the assertion that their Original Kefir did not meet the claimed probiotic count. Lifeway references U.S. Food and Drug Administration food labeling laws, which dictate that a product “must provide all nutrient and food component quantities in relation to a serving size.” Lifeway’s label on their 32-ounce bottle says that the serving size of kefir is 1 cup, making the claim of 25-30 billion CFUs per serving size accurate.

The study results, Lifeway notes in their statement, were “premised upon an erroneous assumption that Lifeway claims it has 25-30 billion CFUs per gram” rather than per serving size.

“The authors’ flawed assumption is perhaps a result of their lack of familiarity with FDA labeling requirements or a result of merely overlooking the details in order to support their intended conclusions going into the testing,” reads a statement from Lifeway.

In fact, Lifeway points out, the study’s “erroneous conclusion premised upon the flawed assumption…actually proves the accuracy of Lifeway’s claim of 25-30 billion CFUs per (8 ounce) serving.”

Redwood Hill Farm, too, refutes the study’s conclusion. Their Goat Milk Kefir currently includes the phrase “millions of probiotics per sip” on its label. The label referenced in the study was an old version that claimed “hundreds of billions” of probiotics, which was discontinued last year. According to Redwood Hill Farm, that old label was based on third-party testing that confirmed hundreds of billions of CFUs per 8-ounce serving. But careful review of the kefir’s probiotic counts in 2019-2020 found some CFUs in the hundreds of billions and others in the tens of billions. Redwood Hill changed their label to millions rather than billions “to be absolutely sure that we could meet our target claim on a consistent basis.”

Variation in CFU counts is common in traditional plating testing techniques. Redwood Hill referenced a study published in Nutritional Outlook that found that plating results can vary 30-50%.

“Given the challenges around probiotic CFU enumeration, we were not too surprised to see a discrepancy between the number of CFUs in our Goat Milk Kefir found in the study and our past analyses,” reads the statement from Redwood Hill Farm. “Like all living organisms, probiotics are challenging to control and measure. A particular microorganism’s ability to reproduce is impacted by a variety of factors, including temperature, oxygen level, variations in the nutrient composition of the milk, and pH level. Our kefir has a sixty-day shelf life and during that time the different types of bacteria in the product will peak and die-off in relation to the conditions those particular bacteria like. For example, fermented dairy products naturally become more acidic (lower pH) as they age and while some bacteria thrive in acidic environments, others’ reproduction is stunted. This makes the exact CFU count rather volatile not only from bottle to bottle, but also throughout the timespan between when that bottle leaves our facility and when it expires.”

Redwood Hill Farm’s most recent testing measured 400 million CFUs per gram or 96 billion per serving (1 cup). These figures compare with what the study found — 193 million CFUs per gram or 46 billion per serving.

“Although the University of Illinois study found only half the probiotic cells that our study did, this is actually not that wide of a variation in bacteria reproduction based on all of the conditional factors outlined above,” their statement reads.

Species Count

The study’s test results found all kefir brands contained species not on the label. Lifeway notes their culture claims are based on the time of manufacture, not on expiration date. “Moreover, the authors validate that all of the claimed culture species except for the bifidos, Leuconostoc and L. reuteri, (which could be at a low concentration due to time of shelf-life), were identified in their testing,” reads Lifeway’s statement.

Redwood Hill Farm says that, based on the study results (that “2 Lactobacillus delbrueckii subspecies or 3 Lc. lactis subspecies could not be identified” in their kefir), they are pursuing further analysis. They’ve contacted their culture supplier for further insight, and are sending new samples to a third-party lab.

“These cultures are at the heart of the product and are what transforms the goat milk into a yogurt drink with its characteristic thick and creamy texture and tart flavor,” reads the Redwood Hill Farm statement. “It’s difficult to understand how these core active agents in the kefir could not be present in the product at any stage in its lifecycle.”

DNA vs. Plating Methodology

The study utilized both DNA sequencing and traditional plating methodologies, even though plating testing alone is considered the industry standard for kefir. Plating testing for kefir is done in a microbiology laboratory where it’s incubated to determine bacteria colony growth.

The study itself notes: “Limitation of DNA-based sequencing methods could explain why taxa stated on labels were not detected and why unclaimed viable species were identified.”

Lifeway points out: “This concession as to testing limitations is critical to note as it is but one explanation of many as to why various species may have not been detected. First and foremost, the authors fail to validate the DNA extraction method to establish that it delivers all the available DNA in the type of dairy product analyzed; for example, they do not appear to have broken down the calcium bonds. Further, they appear to not have undertaken the required extra enzymatic treatments. Moreover, for their microanalysis, they are using MRS [a method for cultivation of lactobacilli] but only incubating for 48 hours. As most kefir products would contain a significant amount of Lactococci, there is a high chance of not detecting this species unless you go to 72 hours of incubation. Another unknown important factor in the testing is the time period within the cycle of the shelf-life of the product that was tested. This is critical as the longer the product sits on a shelf, the fewer number of live and active bacteria will be present.”

Meanwhile, Redwood Hill Farm says “our team will continue to educate ourselves on the application of DNA sequencing technology to fermented food product probiotic count analysis and what opportunities and limitations this methodology may offer versus traditional plating techniques.”

- Published in Science

Advances in Yeast

We’re in the midst of a yeast revolution, as genome sequencing creates opportunity for cutting-edge advances in fermented foods and drinks. Yeast will be at the forefront of innovation in fermentation, for new flavors, better quality and more sustainability.

“Understanding and respecting tradition is a key part of this. These practices have been tested for hundreds and thousands of years and they cannot be dismissed. There’s a lot the science can learn from tradition,” says Richard Preiss of Escarpment Laboratories. Priess was joined by Ben Wolfe, PhD, associate professor at Tufts University (and TFA Advisory Board member), during a TFA webinar, Advances in Yeast.

Preiss continues: “There’s still a place for innovation, despite such a long history of tradition with fermentation. A lot of the key advances in science are literally a result of people trying to make fermentation better.”

Wolfe, who uses fermented foods and other microbial communities to study microbiomes in his lab at Tufts, said “there’s this tradition versus technology conflict that can emerge.”

“I tell my students when I teach microbiology that much of the history of microbiology is food microbiology, it is actually food microbes, and they really drove the innovation of the field so it really all comes back to food and fermentation,” Wolfe says.

The technology relating to the yeasts used in fermentation has expanded enormously over the last decade, due heavily to advances in genome sequencing. Studying genetics allows labs like the ones Priess and Wolfe run to find the genetic blueprint of an organism and apply it to yeast. Drilling down further, they can tie genotype to phenotype to determine characteristics of a yeast strain. This rapidly expanding technology will disrupt and advance fermentation.

Priess predicted three areas of development for yeast fermentation in the coming years:

- Novelty Strains

Consumers have accelerated their acceptance of e-commerce during the Covid-19 pandemic and they’ll do the same for biotechnology, Priess says.

“Our industry does thrive on novelty,” he adds, noting there are beer brands already creating drinks with GMO yeast. “Craft beer is going to be the first food space where the use of GMOs is widespread — we’re seeing that play out a lot faster than I ever thought it would be with some of these products already on the market. Novelty does have value.”

Wolfe noted many consumers shudder at the idea of a GMO food or beverage, but microbes in beer are dead. Consumers are not drinking a living GMO in beer.

Yeasts also already pick up new genetic material naturally, through a process called gene transfer.

“It’s part of the evolutionary process that all microbes go through,” Wolfe says. “From my own lab and from other labs, cheese and sauerkraut and all these other fermented foods are showing so much genetic exchange that’s already happening.”

- Climate Change

The food industry must address growing concerns about climate change. Priess predicts breeding plants — like barley, hops and grapes — that are more drought-tolerant, or even using yeast technologies to increase yields or the rate of fermentation.

“Craft beer is massively wasteful,” Priess says. It takes between three to seven barrels of water to make one barrel of beer. “It is something we’re going to have to reckon with the next 10 years.”

Yogurt and cheese, too, produce large amounts of waste products.

- Ease of Genomics

The cost and time of genome sequencing has reduced significantly. It used to cost thousands of dollars and take many weeks to document a yeast genome. Now, it can be done for $200 in only a few days.

“The tools to deal with the data and get some meaning from it have never been more accessible. It’s incredibly powerful,” Priess says. “We’re developing solutions for products without millions of dollars.”

Priess does not agree with companies patenting yeasts, “it’s murky territory.” He believes fermentation and science should be about collaboration, not ownership and protection.

“Working with brewers and other fermentation enthusiasts, it’s this incredibly open and collaborative space compared to a lot of the industries,” he says. “I think that’s like our secret weapon or our secret value is that fermentation is so open in terms of access to knowledge as well as in terms of people being willing to experiment and try new things. That’s how it’s able to develop so quickly.”

- Published in Food & Flavor, Science

Artisanal Agave Spirits

Agave spirits are quickly becoming sought-after alcoholic beverages. Hearty desert plants, agaves spend years or even decades developing indigestible carbohydrates that can be hydrolyzed for fermentation, resulting in spirits like mezcal.

“We’re at a golden age of agave spirits right now,” says Lou Bank, cohost of the Agave Road Trip podcast. Bank and cohost Chava Periban shared the centuries-old fermentation processes used to create mezcal in the TFA webinar Artisanal Agave Spirits.

Adds Periban: “The beautiful thing about mezcal is we want diversity and you can use any agave under the sun to be able to make mezcal, which makes this category probably the most intensively diverse category in the spirits world.”

Tequila vs. Mezcal

Tequila and mezcal are both spirits distilled from fermented agave. But tequila can be made only from the blue Weber variety of agave and is made by steaming the agave’s heart (pina) in above-ground ovens. Mezcal can be from any of 30 types of agave and is made by cooking the agave in underground pits lined with lava rocks.

As the market for tequila grew, the term “tequila” was declared intellectual property of the Mexican government in 1974. Extensive regulations were established that, among other things, required tequila — formerly considered a regional type of mezcal — to come from only a specified area of Mexico.

Regulations for mezcal weren’t established until 1994, when it received its own Denomination of Origin. Similar to how champagne can only be made in a specific part of France, mezcal can only be made in nine of Mexico’s 32 states.

Periban and Bank point out a major issue with this certification process for mezcal. It ostracizes rural mezcaleros who may not have the money for certification or may not reside within the geographical boundaries.

“A lot of the communities and the traditions that nourish this nostalgia and this beauty of mezcal, they cannot use this word anymore to name their own spirits, the same spirits that they have been producing for centuries in their communities,” Periban says.

Adds Bank: “We love the flavors, but we are very much about preserving the process and in preserving the process, the number one ingredient in the process are the men and women who make the spirits.”

Bank runs a non-profit, SACRED (Saving Agave for Culture, Recreation, Education and Development), that helps improve lives in the rural Mexican communities where heirloom agave spirits are made.

Wild Fermentation of Agave Spirits

Tequila is made similarly to most alcohol — the producer pitches in a yeast to eat the sugar, picking a specific yeast for the desired flavor.

On the other hand, agave spirits such as mezcal and pulque are made in open air fermentation vats. Wild yeasts off nearby fruit trees change the flavor.

Bank estimates only 1 out of every 100 different commercial tequilas is made using pre-industrial, heritage processes. Mezcal, meanwhile, is just the opposite, with 1 in 100 bottles made using commercialized techniques.

“As the world gets more interested (in mezcal), you’re going to see more industrialization and you’re going to see less and less of this beautiful handmade stuff.”

Mezcal’s flavor palate varies by region, the agave type and the processing. Most mezcal is made and sold locally, to neighbors for weddings and religious festivities.

“If you’re making mezcal, you’re not just selling the product. You’re selling the drink that’s going to be part of their most important days of their lives,” Periban says.

Artisanal drinks with natural ingredients are on the rise, especially in America. Mark McTavish, president of 101 Cider House and co-founder & CEO of Pulp Culture (and TFA Advisory Board member), doesn’t see this trend slowing.

Mezcal, he says, will aid growth in the category, as it’s an alcoholic beverage that, instead of chugging, you sip to taste the complexity of the flavors.

“I really love fermentation and what it gives to a beverage, and I think it’s way more than just alcohol,” McTavish says. “There’s just such a richness there to the connection to a sense of place and a people behind it…that’s why fermentation is so beautiful.”

- Published in Food & Flavor

Dairy-Free “Vegurt”

Chr. Hansen, a global bioscience supplier of ingredients, has developed Vega Culture Kits, a new line of probiotic starter cultures that can be used to create plant-based yogurt. “Vegurt,” a shortening of vegan or vegetarian yogurt, is the name being used for this non-dairy product. This term was created in reaction to the European Parliament’s current debate over whether plant-based products can use dairy-related terms like yogurt and milk.

“Vegurt seemed a catchy and suitable category name compared to having to sprain our tongues calling them ‘fermented plant-based alternatives to dairy yogurt,’” said Dr. Ross Critenden, senior director for commercial development at Chr. Hansen.

The Vega Culture Kits are designed to “robustly ferment” any dairy-free plant base, like nuts, cereals, legumes or seeds. The Vega Culture will appear as “culture” on ingredient lists, in the same way that dairy yogurts include “culture” when cultures or probiotic strains are added.

Read more (Food Navigator)

- Published in Science