Pandemic Closes 75-Year-Old Sauerkraut Producer

Beloved Canadian sauerkraut brand Tancook is shutting down after 75 years. The iconic Nova Scotia traditional sauerkraut, which is packaged in a milk carton, was even the subject of Philip Moskovitz’s book Adventures in Bubble and Brine: What I Learned from Nova Scotia’s Masters of Fermented Foods, Craft Beer, Cider, Cheese, Sauerkraut, and More.

Owners Hatt and Son Ltd. announced the closure on social media, posting “due to financial implications of the Covid-19 pandemic, we have made the difficult decision to end production.” Owner Cory Hatt said “difficult decisions” had to be made and he did not want to discuss it further with media outlets.

Tancook’s history is rich in Canada. German immigrants found that cabbage thrived on Nova Scotia’s Big Tancook Island, where they fertilized it annually with seaweed. Tancook sauerkraut became a popular condiment for seafaring ships, who would pick up barrels of it to combat scurvy in sailors and provide them nutrition during long, maritime winters.

Tancook Brand Sauerkraut was later produced commercially in Lunenburg County in Nova Scotia, using the same recipe brought from the island by the great-grandfather of Hatt. It remained a traditionally fermented product.

A social media campaign has already launched, aiming to find a buyer for the brand.

Read more (CBC)

- Published in Business

Food and Beverage Laws Passed in 2021

After the Covid-19 pandemic shortened their legislative sessions last year, lawmakers across the 50 states had a productive year in 2021. State leaders were able to pass hundreds of bills relating to food, beverages and food service.

Numerous new laws were aimed at helping restaurants survive — permitting permanent outdoor dining spaces, allowing carryout food services and to-go alcohol sales. Many of these regulations had been enacted in 2020 as temporary, emergency measures to aid restaurateurs, but expired this year.

This year was also big for cottage food laws. As more people experimented in their home kitchens during the pandemic, there was pressure to modernize cottage food laws. Over half the states updated their laws in 2021, regulating sales of homemade food.

Below are the key food, beverage and food service laws passed this year in, alphabetically, Alabama through Maryland. We’ll feature the balance of the states — Massachusetts to Wyoming — in TFA’s next newsletter (January 12, 2022).

Alabama

HB12 — Extends protections granted for cottage food businesses to include roasted coffees and gluten-free baking mixes.

HB539 — Increases the amount of alcohol which breweries and distilleries can sell to customers for off-premise consumption.

SB126 — Allows licensed state businesses to deliver wine, beer and spirits to customers’ homes.

SB160 — An update to Alabama’s cottage food law, SB160 allows for most non-perishable foods to be made in home-based food businesses without commercial licenses (instead of just only baked goods, jams/jellies, dried herbs and candies). It also removes the $20,000 sales limit for home-based food businesses. It also allows online sales and in-state shipping of products.

SB167 — Permits Alabama wineries to sell directly to consumers at special events.

SB294 — Authorizes wine manufacturers to sell directly to retailers without a distributor.

SB397 — Allows opening of wineries in Alabama’s 24 dry counties. The wineries will be allowed to produce and operate in a dry county, but they may not sell on premise.

Alaska

HB22 — Legalizes herd share agreements for the distribution of raw milk in the state.

Arizona

HB2305 — Amends law to allow two or more liquor producers, craft distillers or microbrewery licenses at one location.

HB2753 — States that licensed producers, craft distillers, brewers and farm wineries are subject to rules and exemptions prescribed by the FDA. Exempts production and storage spaces from state regulation.

HB2773 — Allows bars, liquor stores and restaurants to sell cocktails to-go.

HB2884 — Exempts alcohol produced on premise in liquor-licensed businesses from food safety regulation by the Arizona Department of Health Services, which adds rules regarding production, processing, labeling, storing, handling, serving, transportation and inspection. Specifies that this exemption includes microbreweries, farm wineries and/or craft distilleries.

Arkansas

HB118 — Permits the sale of cottage foods over the internet. Interstate sales are permitted if the producer complies with federal food safety regulations.

HB1228 — Allows for municipalities in dry counties to apply to be an entertainment district, just like in wet counties.

HB1370 — Establishes mead as an allowed liquor for a small farm winery — and allows wineries to ship mead. Also allows for mead to be taxed in the same manner as wine.

HB1426 — Establishes the Arkansas Fair Food Delivery Act, stating that a food delivery platform (like UberEats) must have an agreement with a restaurant or facility to take food orders and deliver food prepared.

HB1763 — Allows distilleries to self distribute their own products and allows out-of-state, direct-to-consumer shipments.

HB1845 — Restricts advertising alcohol in microbrewery-restaurants in dry counties.

SB248 — Replaces Arkansas’ cottage food law with the Food Freedom Act. Allows all types of non-perishable foods to be sold almost anywhere without a food safety license and certification, including grocery stores and retail shops.

SB339 — Allows permitted restaurants to sell on-the-go alcoholic beverages.

SB479 — Allows restaurants with alcohol beverage permits to expand outdoor dining without approval of the Alcoholic Beverage Control Division.

SB554 — Authorizes beer wholesalers to distribute certain ready-to-drink products.

SB631 — Authorizes a hard cider manufacturer to deliver hard cider.

California

AB61 — Allows restaurants and bars with alcohol licenses that added temporary, outdoor sidewalk dining spaces during the Covid-19 pandemic to continue serving alcohol in these spaces.

AB239 — Allows wineries to refill wine bottles at off-site tasting rooms, similar to breweries reusing growlers

AB286 — Requires third-party delivery companies to itemize cost breakdowns of delivery transactions to both restaurants and customers.

AB425 — Updates regulations regarding definitions, assessments, fees and funding mechanisms for the Dairy Council of California.

AB831 — Mandates that all labels on cottage food must include the disclaimer “Made in a Home Kitchen” along with the producer’s county and cottage food permit number.

AB941 — Establishes a grant program for counties to apply for farmworker resource centers, supplying farmworkers and their families information on education, housing, payroll, wage rights and health services.

AB962 — Requires the creation of a returnable bottle system in the state by 2024. Allows recyclable bottles to be washed and refilled by beverage producers rather than being crushed for recycling.

AB1144 — Updates California’s outdated cottage food laws, raising sales limit to either $75,000 (Class A permits) or $150,000 (Class B permits) and simplifying the approval process for sampling cottage food products. Also allows homemade food to be sold online.

AB1200 — By 2023, no eatery in California is permitted to distribute or sell food packaging that contains regulated perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances or PFAS. Manufacturers of food packing must use the least toxic alternative when replacing their food packaging. Food packaging includes food or beverage containers, take-out containers, liners, wrappes, eating utensils, straws, disposable plates, bowls and trays.

AB1267 — Allows licensed manufacturers, distributors and sellers of alcoholic beverages to donate a portion of beverage purchases to a nonprofit.

AB1276 — Requires California eateries to only give take-out customers single-use utensils and condiment packets if they ask for them.

AR15 — Establishes Nov. 22 as Kimchi Day in the state.

SB19 — Allows wineries to open additional off-site tasting rooms without applying for a new license (former law allowed for only one off-site tasting room).

SB314 — Allows restaurants and bars that added temporary, outdoor sidewalk dining spaces during the Covid-19 pandemic a one-year grace period to apply for permanent expansion.

SB389 — Allows restaurants and bars to serve to-go alcohol alongside a meal.

SB453 — Establishes an Agricultural Biosecurity Fund specifically for the California State University system’s Agricultural Research Institute. The California State University’s 23 campuses and 8 off-campus branches can then use that fund to apply for grants related to supporting research on agriculture biosecurity, best practices around infectious agents hurting the state’s animal herds and plant crops.

SB517 — Authorizes a licensed beer manufacturer who obtains a beer direct shipper permit to sell and ship beer directly to a resident of the state for personal use.

SB535 — Makes it unlawful to manufacture or sell imitation olive oil in the state. Also restricts using “California Olive Oil” on a label unless 100% of the oil is derived from olives grown in California. The label can also only share that the oil comes from a specific region of California if at least 85% of the olives were grown in that region.

SB721 — Establishes Aug. 24 as California Farmworker Day.

Colorado

HB1027 — Extends sales of to-go alcohol from licensed restaurants and bars to 2026.

HB1162 — The Plastic Pollution Reduction Act, the law bans single-use plastic bags and containers made from polystyrene (styrofoam) for restaurants and other retailers by 2024. All stores will also implement a 10-cent bag fee for plastic and paper bags by 2023.

SB35 — Prohibits third-party restaurant delivery services from cutting pay to a driver to comply with fee limits. Also prohibits third-party delivery services from putting restaurants on their platforms without the eateries’ permission.

SB235 — Sends the Department of Agriculture $5 million for energy efficiency and soil health programs.

SB270 — Allows more Colorado wineries, cideries and distillers to attain a pub license and sell a variety of food in addition to their craft beverage. Current law puts small limits on the amount of craft drink made for a brewery to sell food, leaving out larger Colorado producers.

Connecticut

HB5311 — Enables permitted transporter to sell and serve alcohol on boats, motor vehicles and limousines.

HB6610 — Codifies expanded outdoor dining, allowing municipalities to close off streets and sidewalks for outdoor restaurant dining space.

SB894 — Allows patrons to pour their own alcoholic drinks at restaurants and bars. Will allow self-pour automated systems to be used in the state’s dining establishments.

HB6580 — Expands food agricultural literacy programs of study and community outreach, by increasing certification, education and extension programs with rural suburban and urban farms for students in grades Kindergarten through 12th grade.

Delaware

HB1 — Allows restaurants to continue selling to-go alcohol beverages. The bill also allows restaurants and bars to continue using outdoor dining spaces originally used during the Covid-19 pandemic.

HB46 — Allows brewery-pub and microbrewery license holders to brew, bottle and sell hard seltzers and other fermented beverages made from malt substitutes. Also includes a specific tax on fermented beverages.

HB143 — Reduces the amount of licensed taprooms to only one taproom within a ½ mile from another taproom.

HB212 — Increases minimum thickness for plastic bags (used by grocery stores and restaurants) to qualify as a reusable bag from 2.25 mils to 10 mils.

SB46 — Allows wedding venues and event centers licensed as bottle clubs to allow customers to bring alcoholic beverages on premise.

Florida

HB751 — Authorizes issuance of special licenses to mobile food vehicles to sell alcohol beverages within certain areas.

HB1647 — Allows more Orlando eateries to sell alcohol. Allows eateries with a smaller footprint (80-person capacity; formerly 150-person capacity) to sell beer, wine and spirits in six additional Orlando Main Street Districts.

SB46 — Increases production limits for distilleries from 75,000 gallons a year to 250,000 gallons. Eliminates the “six bottles per person per brand per year” requirement. Also allows craft distilleries to qualify for a vendor’s license to conduct tastings at Florida’s fairs, trade shows, farmers markets, expositions and festivals.

SB148 — Authorizes restaurants or bars also holding a public food service license to sell or deliver alcoholic beverages in sealed, to-go containers.

SB628 — Establishes a new program, the Urban Agriculture Pilot Project, to distinguish between traditional rural farms and emerging urban farms. Exempts farm equipment used in urban agriculture from being stored in certain boundaries.

SB663 — Updates Florida’s cottage food law to allow shipping of products, and raises the sales limit for shipped cottage food from $50,000 to $250,000. The bill also prevents counties or cities from banning cottage food businesses (Ed. note: Florida’s largest county, Miami-Dade, prohibits cottage food businesses).

SR2041 — Establishes a Food Waste Prevention Week in the state to acknowledge the importance of conserving food and preventing food waste.

Georgia

HB273 — Allows local municipalities to pass an ordinance, resolution or referendum election to authorize allowing a liquor store to open in their jurisdiction

HB392 — Allows a person to have a mixed cocktail or draft beer from the hotel delivered to their room by a hotel employee.

HB498 — Expands eligibility requirements for the state’s tax exemption for agricultural equipment and farm products. Any family-owned farm entity (defined as two or more unrelated, family-owned farms) can now share equipment, land and labor without losing ad valorem tax exemptions enjoyed by stand-alone family farms.

HB676 — Creates a legislative advisory committee on farmers’ markets (Farmers’ Markets Legislative Advisory Committee), made up of five members from the state’s Senate and House.

SR155 — Recognized February 17 as State Restaurant Day.

SB219 — Permits small brewers to sell alcohol for consumption on their premise. Allows state’s breweries to transfer beer between locations.

SB236 — Extends the Covid-era rule that allows restaurants to sell to-go alcohol.

Hawaii

HB817 — Requires state agencies to purchase an increasing amount of locally grown food.

HB237 — Earmarks $350,000 to the department of agriculture for the mitigation and control of the two-lined spittlebug, which has damaged nearly 2,000-acres of pasture land.

SB263 — Establishes a “Hawaii Made” program and trademark, to promote Hawaiian-made products.

Idaho

HB51 — Amends existing law to provide nutrient management standards on dairy farms. Allows dairy farmers the option of using phosphorus nutrients.

HB232 — Changes the distribution of tax on high-alcohol-content beer from the state wine commission to the state hop growers commission, helping promote the craft industry.

Illinois

HB2620 — Allows small breweries, meaderies and winemakers to distribute their products to local bars, grocery stores and liquor stores directly rather than through a third party.

HB3490 — Amends Illinois Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act, which says, if a restaurant includes milk as a default beverage in a kid’s meal, the drink must be dairy milk and contain no more than 130 calories per container or serving.

HB3495 — The Brewers Economic Equity & Relief Act, allows for limited brewpub self-distribution, permanent delivery for small alcohol producers, direct-to-consumer shipping for in-state and out-of-state brewers and distillers and self-distribution for manufacturers producing more than one type of alcohol.

HR33 — Creates the Illinois Good Food Purchasing Policy Task Force to study the current procurement of food within the state and explore how Good Food Purchasing can be implemented to maximize the procurement of healthy foods that are sustainably, locally and equitably sourced.

HR46 — Urges the Illinois Department of Agriculture to study the effects and the types of land loss to Black farmers. Calls for state support and capacity building for Black farming communities across the state and a dedication to helping grow agriculture in rural, urban, and suburban areas.

HR117 — Urges the United States Department of Agriculture and the United States Department of Commerce to increase the exportation of Illinois dairy products to other nations.

SB2007 — The Home-to-Market Act, updates the state’s Illinois Cottage Food Law. Expands sales avenues for cottage food producers, allowing sales at fairs, festivals, home sales, pick-up, delivery and shipping (cottage food was previously only allowed to be sold at farmers markets).

Indiana

HB1396 — Updates many of Indiana’s outdated alcohol laws, some from the Prohibition Era. Amended various sections of Indiana’s alcohol code impacting permittees, trade regulation and other various definitions.

HB2773 — Allows bars, liquor stores and restaurants to permanently sell to-go alcohol orders, originally allowed temporarily during the Covid-19 pandemic.

SB144 — Allows bulk wine purchasing limits for farm wineries to apply only to wine sold directly to a consumer and not to wine sold through a wholesaler. Also allows the holder of an artisan distiller permit to also hold a distiller’s permit.

SB185 — Creates a working group made up of industry organizations, food safety experts, Indiana State Department of Health, Indiana State Board of Animal Health and Indiana State Department of Agriculture to submit recommendations to the state concerning home-based vendors and cottage food laws.

Iowa

HB384 — Updates rules regarding alcohol licenses. Lengthens the hours of sale for alcoholic beverages on Sunday.

HF766 — Allows home delivery of alcoholic beverages from bars and restaurants by third-party delivery services, such as Uber or DoorDash.

Kansas

HB2137 — Allows bars, liquor stores and restaurants to permanently sell to-go alcohol orders, originally allowed temporarily during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Kentucky

HR3 — Recognizes March 23 as Agricultural Day in the state.

HR19 — Recognizes June as Dairy Month, honoring the state’s dairy workers.

SB15 — Allows a microbrewery licensee to sell and deliver up to 2,500 barrels of product to any retail licensee and to set forth terms of contracts between microbrewers and distributors.

SB67 — Allows bars, liquor stores and restaurants to permanently sell to-go alcohol orders, originally allowed temporarily during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Louisiana

HB192 — Authorizes credit card payment to manufacturers and wholesale dealers of alcoholic beverages (when previously cash was only allowed).

HB219 — Allows the delivery of ready-to-drink alcohol beverages (sold in manufacturer sealed containers), allowing brewers with a brewing facility to self-distribute.

HB269 — Allows authorized state employees to destroy meat, seafood, poultry, vegetables, fruit or other perishable food of foreign origin which are subject of a current import ban from the federal government.

HB291 — Allows self-distribution to any brewer who operates a brewing facility in the state.

HB706 — Adds microwinery to microdistillery permits.

HR104 — Designates May 19, 2021, as Louisiana Craft Brewers’ Day in the state.

HR210 — Authorizes a state subcommittee to study and make recommendations to the government on the regulation of the growing craft brewing industry in the state.

Maine

SB133 — Clarifies that licensed Maine manufacturers of spirits, wine, malt liquor and low-alcohol spirits products may sell and ship their products to a person located in another state.

SB205 — Allows bars and restaurants to permanently sell to-go alcohol orders through take-out and delivery services if the liquor is accompanied by a food order. Also temporarily permits licensed Maine distilleries that operate tasting rooms but do not operate licensed on-premise retail to sell spirits through take-out and delivery services accompanied by a food order.

SB306 — Temporarily waives certain requirements for relicensing for restaurants that serve liquor to help food establishments during the Covid-19 pandemic.

SB307 — Allows all Maine alcohol manufacturers to sell directly to out-of-state consumers (current law only allows wine to be sold out-of-state).

SB479 — Amends definition of “low-alcohol spirits product” by raising the maximum alcohol level of a low-alcohol spirits product from 8% to 15%.

SB630 — Prohibits shelf-stable products from being sold as cider. Products that do not require refrigeration or are heat-treated cannot be labeled as cider.

SB636 — Establishes the Local Foods Fund, which helps schools purchase produce and other minimally processed foods from local farmers and producers.

SB822 — An act affirming that food seeds are a necessity in the state.

Maryland

HB185 — Prohibits an alcoholic beverages license holder from requiring that an individual buy more than one bottle, container or other serving of alcohol at a time.

HB264 — Requires entities that generate at least two tons of organic waste per week to arrange for disposal alternatives, like reduction, donation, animal feed or composting.

HB269 — Establishes the Urban Agriculture Grant Program in the Department of Agriculture to increase the viability of urban farming and improve access to urban-grown foods.

HB 555 — Repeals a prohibition on allowing drugstores to apply for a liquor license.

HB1232 — Codifies emergency orders to grant permanent to-go delivery of alcohol and online shipment privileges.

SB205 — Authorizes local alcoholic beverage licensing boards to temporarily allow restaurants and bars to sell to-go alcoholic beverages. Also requires Maryland’s Alcohol and Tobacco Commission and the Maryland Department of Health to study expanding alcohol access.

SB821 — Codifies the governor’s 2020 executive order to grant alcohol delivery and shipment. Also allows permitting to serve alcohol at off-premise, special events.

The Rise of Fermented Foods and -Biotics

Microbes on our bodies outnumber our human cells. Can we improve our health using microbes?

“(Humans) are minuscule compared to the genetic content of our microbiomes,” says Maria Marco, PhD, professor of food science at the University of California, Davis (and a TFA Advisory Board Member). “We now have a much better handle that microbes are good for us.”

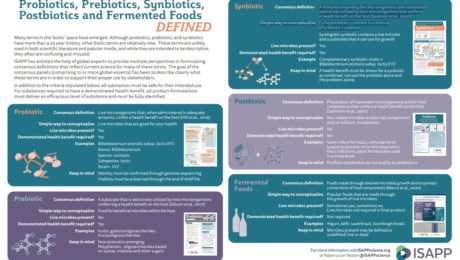

Marco was a featured speaker at an Institute for the Advancement of Food and Nutrition Sciences (IAFNS) webinar, “What’s What?! Probiotics, Postbiotics, Prebiotics, Synbiotics and Fermented Foods.” Also speaking was Karen Scott, PhD, professor at University of Aberdeen, Scotland, and co-director of the university’s Centre for Bacteria in Health and Disease.

While probiotic-containing foods and supplements have been around for decades – or, in the case of fermented foods, tens of thousands of years – they have become more common recently . But “as the terms relevant to this space proliferate, so does confusion,” states IAFNS.

Using definitions created by the International Scientific Association for Postbiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP), Marco and Scott presented the attributes of fermented foods, probiotics, prebiotics, synbiotics and postbiotics.

The majority of microbes in the human body are in the digestive tract, Marco notes: “We have frankly very few ways we can direct them towards what we need for sustaining our health and well being.” Humans can’t control age or genetics and have little impact over environmental factors.

What we can control, though, are the kinds of foods, beverages and supplements we consume.

Fermented Foods

It’s estimated that one third of the human diet globally is made up of fermented foods. But this is a diverse category that shares one common element: “Fermented foods are made by microbes,” Marco adds. “You can’t have a fermented food without a microbe.”

This distinction separates true fermented foods from those that look fermented but don’t have microbes involved. Quick pickles or cucumbers soaked in a vinegar brine, for example, are not fermented. And there are fermented foods that originally contained live microbes, but where those microbes are killed during production — in sourdough bread, shelf-stable pickles and veggies, sausage, soy sauce, vinegar, wine, most beers, coffee and chocolate. Fermented foods that contain live, viable microbes include yogurt, kefir, most cheeses, natto, tempeh, kimchi, dry fermented sausages, most kombuchas and some beers.

“There’s confusion among scientists and the public about what is a fermented food,” Marco says.

Fermented foods provide health benefits by transforming food ingredients, synthesizing nutrients and providing live microbes.There is some evidence they aid digestive health (kefir, sourdough), improve mood and behavior (wine, beer, coffee), reduce inflammatory bowel syndrome (sauerkraut, sourdough), aid weight loss and fight obesity (yogurt, kimchi), and enhance immunity (kimchi, yogurt), bone health (yogurt, kefir, natto) and the cardiovascular system (yogurt, cheese, coffee, wine, beer, vinegar). But there are only a few studies on humans that have examined these topics. More studies of fermented foods are needed to document and prove these benefits.

Probiotics

Probiotics, on the other hand, have clinical evidence documenting their health benefits. “We know probiotics improve human health,” Marco says.

The concept of probiotics dates back to the early 20th century, but the word “probiotic” has now become a household term. Most scientific studies involving probiotics look at their benefit to the digestive tract, but new research is examining their impact on the respiratory system and in aiding vaginal health.

Probiotics are different from fermented foods because they are defined at the strain level and their genomic sequence is known, Marco adds. Probiotics should be alive at the time of consumption in order to provide a health benefit.

Postbiotics

Postbiotics are dead microorganisms. It is a relatively new term — also referred to as parabiotics, non-viable probiotics, heat-killed probiotics and tyndallized probiotics — and there’s emerging research around the health benefits of consuming these inanimate cells.

“I think we’ll be seeing a lot more attention to this concept as we begin to understand how probiotics work and gut microbiomes work and the specific compounds needed to modulate our health,” according to Marco.

Prebiotics

Prebiotics are, according to ISAPP, “A substrate selectively utilized by host microorganisms conferring a health benefit on the host.”

“It basically means a food source for microorganisms that live in or on a source,” Scott says. “But any candidate for a prebiotic must confer a health benefit.”

Prebiotics are not processed in the small intestine. They reach the large intestine undigested, where they serve as nutrients for beneficial microorganisms in our gut microbiome.

Synbiotics

Synbiotics are mixtures of probiotics and prebiotics and stimulate a host’s resident bacteria. They are composed of live microorganisms and substrates that demonstrate a health benefit when combined.

Scott notes that, in human trials with probiotics, none of the currently recognized probiotic species (like lactobacilli and bifidobacteria) appear in fecal samples existing probiotics.

“There must be something missing in what we’re doing in this field,” she says. “We need new probiotics. I’m not saying existing probiotics don’t work or we shouldn’t use them. But I think that now that we have the potential to develop new probiotics, they might be even better than what we have now.”

She sees great potential in this new class of -biotics.

Both Scott and Marco encouraged nutritionists to work with clients on first improving their diets before adding supplements. The -biotics stimulate what’s in the gut, so a diverse diet is the best starting point.

How a Water Kefir Producer Tanked

Scott Whitley, of failed LAB Water Kefir, shares lessons learned from launching – and then shuttering — the business. Whitley is open about his blunders, providing great insights for fermentation brands.

His first problem: Knowing nothing about the food and beverage industry, and even less about selling a fermented drink. The company used a recipe that contained fermentation blunders, so products exploded on store shelves!

Second problem: Spending too much time on low-leverage activities. The two co-founders were filling tens of thousands of bottles of water kefir themselves — something Whitley says in hindsight “was a big mistake.” They thought they were saving money but, in reality, they weren’t making enough money to stay afloat. Bottles sold for $5.50 at retail, and stores bought them for $3.30. After covering production costs, LAB Water Kefir made only $1.10 per bottle. They were bringing in a few thousand dollars per month, but expenses were over $6,500.

Third problem: Lack of consumer understanding. The brand sold well at farmers markets, where half the people who approached their stand and sampled the drink would buy a bottle. But they learned that many people didn’t know what water kefir was. Whitley shares the story of watching a man grab a bottle off the shelf, shake it, then open it to drink – and the water kefir shot out of the bottle and all over his face. Also, people don’t go to a grocery store to experiment with a new, pricey drink, so their water kefir didn’t sell well at retail.

Read more about the story behind the brand at Trends.

Read more (Trends)

- Published in Business

Are Alt Meat Sales Slowing?

Despite many indications of skyrocketing growth in the plant-based-meat industry, concerns are increasing at the larger, publicly-traded companies. Beyond Meat’s stock price dropped 50% in the last six months. Kellogg’s MorningStar Farms brand and Canadian meat giant Maple Leaf Foods both reported low last-quarter sales for their plant-based divisions.

Analysts in a Food Dive article disagree as to what’s happening. Some point to the fact that the category has shown consistent growth, with the majority of alternative meat products sold by smaller, private companies that do not share sales figures. No one has a clear view of how smaller, startup brands — who pioneered the industry — are doing.

Others, though, say the market is too crowded. Dozens of plant-based products launched this year, and stores only have so much space for these new alternatives. Naysayers suggest that the novelty has worn off – consumers were curious early on, but now aren’t coming back to buy plant-based meat. Alt meat prices are still high and their flavors and textures aren’t as satisfying as with traditional meat.

Read more (Food Dive)

- Published in Business

The Regulatory Landscape

Collaboration with regulators, not confrontation, is the recommended course of action for fermenters, experts suggest.

“Producers are speaking one language and regulators are speaking another,” says Abigail Snyder, assistant professor of microbial food safety at Cornell University. “Producers are like ‘Hey, this has been produced forever and it has a history of safe production!’ That’s not super meaningful for regulators. Regulators are used to this codified framework that is not necessarily built around fermented foods. There’s a middle ground.”

Snyder spoke with a panel of experts on health and safety regulations during TFA’s conference, FERMENTATION 2021. The consensus: food regulations exist to protect the consumer, but complying with myriad national, state and local laws can be difficult and frustrating to navigate, especially for a fermented food or beverage that utilizes novel food processes.

“Don’t be afraid, don’t feel like you’re going to tick off the inspector,” says Adam Inman, assistant program manager for the Kansas Department of Agriculture Food Safety & Lodging Program. He advises producers to always ask regulators for help. “Even if we start with your recipe and your process and we just document that, that can go a long way as a starting point.”

Jonathan Wheeler, coordinator for special processes at retail for the South Carolina Department of Health & Environmental Control, says if you’re dealing with a regulator unfamiliar with fermentation, ask for a supervisor. Wheeler manages South Carolina’s team of 80-90 regulators and points out that a health inspection should be an education opportunity for the regulator, too.

“We are partners on the same team, just in different roles,” Wheeler says. “Our approach in South Carolina has been driven by the need to educate as well as regulate. You have a voice, it’s part of collaboration and inspectors…are open to input [from producers].”

Still, compliance is not without its challenges.

Soirée-Leone, writer, homesteader and local food advocate, says that food inspection is one of the biggest challenges for smaller producers — especially in rural areas, where resources can be limited. For example, in Tennessee where she lives, home-based food businesses can sell their goods at farmers markets, as long as those items don’t need to be refrigerated. But there’s no rule for food that needs to be frozen,, so producers are allowed by the health department to sell popsicles.

“It’s very challenging, and a lot of people get very frustrated in the process,” she says.

Erin Leigh DiCaprio, assistant professor of cooperative extension at University of California, Davis, notes that regulations differ from state to state — a ferment produced under cottage food laws in one state could need a processed food license in another. She points out every state or county has an extension educator like herself who has the needed technical expertise to work with producers and regulators. DiCaprio specifically works with smaller-scale processors to navigate regulations in California.

Could the U.S. learn from other countries?In Korea, Japan and China, fermented foods and drinks are common, yet regulations are minimal.

“There’s a cultural aspect there… not necessarily advocating eliminating regulations but saying that a culture — and no pun intended in this case — but a culture that’s been used to eating fermented foods for years and had no negative impact. Is there some education to be learned from that?” questions Neal Vitale, the moderator and executive director of TFA.

“We should not be as regulators in a position of trying to jam fermentation processes… into a mold where they all look the same — because they don’t,” Wheeler says. “Educate me as how you want that process to look.”

- Published in Business

Definition & History of Fermentation

“Human civilization simply would not have been possible without fermented foods and beverages…we’re here today because fermented foods have been popular for humans for at least 10,000 years,” says Bob Hutkins, professor of food science at the University of Nebraska (and a recent addition to TFA’s Advisory Board).

Hutkins was the opening keynote speaker at FERMENTATION 2021, The Fermentation Association’s first international conference. His presentation explored the history, definition and health benefits of fermented foods.

Cultured History

The topic of fermentation extends to evolution, archaeology, science and even the larger food industry.

“The discipline of microbiology began with fermentation, all the early microbiologists studied fermentation,” Hutkins says.

Louis Pasteur patented his eponymous process, developed to improve the quality of wine at Napoleon III’s request. The microbes studied back then — lactococcus, lactobacillus and saccharomyces — remain the most studied strains.

“What interested those early microbiologists — namely how to improve food and beverage fermentation, how to improve their productivity, their nutrition — are the very same things that interest 21st century fermentation scientists,” Hutkins says.

Hutkins is the author of one of the books considered gospel in the industry, “Microbiology and Technology of Fermented Foods.” He says that fermented foods defined the food industry. In its early days, it was small-scale, traditional food production that “we call a craft industry now.” At the time, food safety wasn’t recognized as a microbiological problem.

Today’s modern food industry manufactures on a large-scale in high throughput factories withmany automated processes. Food safety is a priority and highly regulated. And, thanks to developments in gene sequencing, many fermented products are made with starter cultures selected for their individual traits.

“But I would say that there’s been kind of a merging between these traditional and modern approaches to manufacturing fermented foods, where we’re all concerned about time sensitivity, excluding contaminants, making sure that we have consistent quality, safety is a vital concern and extensive culture knowledge,” Hutkins says.

Defining & Demystifying

Fermentation — “the original shelf-life foods” — is experiencing a major moment. “Fermented foods in 2021 check all the topics” of popular food genres: artisanal, local, organic, natural, healthy, flavorful, sustainable, entrepreneurial, innovative, hip and holistic. “They continue to be one of the most popular food categories,” Hutkins continues.

Interest in fermentation is reaching beyond scientists, to nutritionists and clinicians. But Hutkins says he’s still surprised to learn how many professionals don’t understand fermentation. To address the confusion, a panel of interdisciplinary scientists created a global definition of fermented foods in March 2021.

“Fermentation was defined with these kind of geeky terms that I don’t know that they mean very much to anybody,” he says.

The textbook biochemical definition of fermentation that a microbiologist learns in Biochemistry 101 doesn’t work for a nutritionist or clinician focusing on fermentation’s health benefits. The panel, which spent a year coming to a consensus, wanted a definition that would simply illustrate “raw food being converted by microbes into a fermented food.” The new definition, published in the the journal Nature and released in conjunction with the International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP), reads: “Foods made through desired microbial growth and enzymatic conversions of food components.”

Fermentation in 2022

Hutkins predicts 2022 will see more studies addressing whether there are clinical health benefits from eating fermented foods. The groundbreaking study on fermented foods at Stanford was important. It found that a diet high in fermented foods increases microbiome diversity, lowers inflammation, and improves immune response. But research like this is expensive, so randomized control trials are few.

Fermented foods could also make their way into dietary guidelines.

“Fermented foods, including those that contain live microbes, should be included as part of a healthy diet,” Hutkins says.

- Published in Food & Flavor, Science

Analyzing Mexico’s Traditional Fermented Beverages

A research team has made the first comprehensive analysis of Mexico’s traditional ferments. Utilizing the country’s native cacti, agaves and maize, these diverse beverages are unique to their region. But they are poorly studied, and some are endangered as they fall out of style with younger generations.

“Many of Mexico’s finest microbiologists and ethnobotanists are giving ever-greater attention to this fascinating but once-forgotten foodscape, but even they are willing to admit that we’re just beginning to scratch below the surface of understanding all the biodiversity in these bottles of blessed ferment,” says Gary Paul Nabhan, research scientist at the Southwest Center of the University of Arizona (U of A).

Researchers in various disciplines (microbiology, ethnoecology and genetics) from five different schools (U of A and four universities in Mexico) took part in the study. The results, Traditional Fermented Beverages of Mexico: A Biocultural Unseen Foodscape, are published in the international journal Foods.

Sixteen traditional Mexican fermented beverages were identified: tepache, pulque, hobo, Mexican wines, colonche, nawait, pozol, sidra, tejuino, tesgüino, taberna, cocoyol, tuba, Mexican palm wine, balché and xtabentún. Those 16 drinks were made from 143 plant species and include 102 genre of microorganisms.

In each region, “a distinctive set of plant roots, leaves, fruits and stems were added as fermentation catalysts, flavorants, colorants and stabilizers,” reads the U of A press release. “A large number of bacterial strains and yeasts — in addition to common brewer’s yeasts and water kefir grains — enabled the nutritional transformation of these raw materials into a wide array of unique nutritionally rich, probiotic beverages.” The team mapped the regional variations and ecological niches of the fermented drinks.

Sustainable Future

The study notes this level of analysis is “indispensable” to promote fair trade and sustainable food production. Industrial mezcal, for example, has created a monoculture of blue agave, and farm labor often works in exploitative conditions.

“These products have been embedded as part of the daily lives of many people, including those currently marginalized rural or Indigenous groups,” the study reads. “The diversity of fermented products is an outstanding reservoir of genetic resources that has high potential to obtain secondary products such as extracts, enzymes, dyes, and others compound that can be involved in global markets and could help to solve problems such as hunger and poverty and may play a key role to reinforce cultural identity..”

Traditional Mexican fermented beverages also provide important nutrients for consumers as the globe battles a changing climate.“The naturally-occurring yeasts and kefir-like tibico grains found in association with prickly pear cacti, saguaro fruit, century plants and desert spoons (sotols) likely tolerate much higher ambient temperatures than those from the semi-arid highlands and wet tropical forests,” Nabhan explains.

Extinct Drinks

Some healthier artisanal drinks “have fallen out of fashion and face local or broad extinction,” the press release notes. In some areas of the country, these “forgotten ferments” are still used in the home, but not commercialized.

“Now that the days of Prohibition are over and there is a great need for arid-adapted crops with highly-efficient water use, some of these traditional agave and cactus varieties should be revived for the local production of healthful beverages,” Nabhan suggests. “In fact, traditional beverages such as tepache, tesguino and colonche have made a comeback in the Tucson, Arizona, region since it received recognition as a UNESCO City of Gastronomy. These traditional beverages are also being employed by mixologists in novel cocktails now being featured in nearly every state of Mexico.

- Published in Food & Flavor, Science

Chocolate Without the Cacao

Cacao is one of the most environmentally harmful and ethically dubious commodities produced on the planet. It plays a huge role in deforestation, uses an alarming amount of water and more than 2 million children work in cacao farms. Yet cacao hasn’t been reimagined the way other foods with similarly harmful footprints have.

“There’s a lot of ethical quandaries around the production of chocolate,” says Johnny Drain, PhD, co-founder of WNWN Food Labs. “Cacao is a huge contributor to climate change, and child labor and slave labor are hardwired into the supply chain.”

Drain’s nickname is the “Walter White of fermentation” because of his work helping pioneering restaurants and bars around the world incorporate fermentation into their food and drink. Now Drain can add “Willy Wonka of chocolate” to his resume. He is co-launching a cacao-free chocolate, next in the wave of alternative products designed to replicate flavor and texture without a harmful production cycle.

A Chocolate-Potato Connection?

WNWN (Waste Not, Want Not, pronounced “Win-Win”) happened by chance. About five years ago, Drain was boiling old, green potatoes, and leaned his head into the steam. He was surprised it smelled like chocolate.

“I had this light bulb moment where I thought ‘There must be some compounds within the skins that are also found in cacao and chocolate.’ I wondered — ‘Could I make chocolate from potatoes? What other weird and wonderful things could make chocolate?’” Drain says.

WNWN plans to release a small-run batch of their chocolate next month. Drain and co-founder Ahrum Pak, a former investment banker and fellow fermenter-turned-food-activist, are calling the product category choc.

WNWN’s choc ingredients are proprietary until its formal release but, as with traditional chocolate, they are plant-based and fermented. Drain describes them as familiar, whole ingredients that are common in an average person’s diet.

“It’s not a Frankenstein, lab-created product, mixing this potion with that potion. We take whole ingredients, we ferment them just as we would chocolate, then we end up with this delicious chocolatey paste that goes into a quite conventional chocolate-making procedure,” Drain adds.

WNWN also replaces cocoa butter — made from cacao pods — with plant-based oils. Cocoa butter is what gives traditional chocolate a silky, creamy texture as it melts in your mouth.

Fermented Flavors

At the heart of choc’s flavor, though, is fermentation.

“Cacao is fermented to make chocolate in the same way our product is fermented. We use similar, friendly microbes to create complexity,” he says. “We’re recreating that flavour profile of chocolate that we all know and love using the same fundamental techniques that are used to make chocolate.”

High-quality chocolate contains roughly 600 different flavor and aroma molecules. Cacao fermentation involves lactic acid and acetic acid bacteria, along with various yeasts, to create its flavor.

“If you didn’t have that cocktail of microbes, you would end up with something that only tastes vaguely like the chocolate we know and love,” he adds. “At the heart of this is fermentation. The product that we have, if we produced it without the fermentation processes, it wouldn’t taste anything like chocolate, just like if you eat a raw cocoa bean or even a roasted, unfermented cocoa bean, it doesn’t really taste like chocolate. You have to have that very complex cascade of chemical reactions, made possible by the fermentation, to get the final chocolate flavour.”

The Next Big Alt Movement?

Drain is quick to point out WNWN is not the only company trying to create what he and Pak have coined “alt-chocolate.” Three companies — QOA, Voyage Foods and Cali-Cultured — all officially launched in the past three months.

Some of these companies have been operating in stealth mode for a number of years but made official launches once word of competitors began to circulate. QOA and Voyage appear to be using approaches similar to that of WNWN. CaliCultured is using a syn-bio precision fermentation route to modify yeast cells to produce lab-grown cacao cells that are genetically identical to those found in the wild.

Drain says he’s encouraged by the other companies.

“It’s exciting that there’s multiple people working in this space,” he says. “Look at the plant milk space or alternative protein space — there’s definitely plenty of room in this marketplace too, and collectively we are all doing this because we care about the ethical and environmental damage being wrought by the current cacao supply chain.”

European and American consumers historically dominate chocolate sales, but chocolate sales all over the world are increasing.

Drain and Pak feel that a shake-up in the industry at the top is needed. Huge international producers are responsible for the vast majority of global chocolate. Mars, Nestle and Hershey promised over 20 years ago to stop using child laborers, but reports say the problem continues.Similarly, these companies pledged a decade ago to source more sustainable chocolate, but negative environmental problems from cacao continue to increase.

“The way in which we consume food has to change. It’s unrealistic that millions of tons of mass-produced cacao is somehow ethically- and sustainably-produced,” Pak says.

Drain adds; “So, really, we’re not anti-chocolate, we’re anti-big-chocolate produced in unethical, unsustainable ways.”

Recreating Food

Chocolate is merely the first challenge that WNWN wants to address. Coffee and vanilla are next, foods with similar human rights and sustainability concerns. The company is building a software system that can ideate fermentation pathways for creating sustainable, flavour-identical analogs to delicious – but unsustainable – products.

“When you really start looking at how most of the world’s food is produced and consumed, there are so so many cases where it’s produced in a really terrible and damaging way,” Drain says. But “the market wouldn’t have been ready for a product like this five years ago. People are becoming much more aware of where their food comes from. People are thinking about ‘How do I make my purchasing habits, my diet better for the planet in a way that I don’t have to sacrifice the flavors and taste that I love?’ There will be work to do. But people are more receptive now that fermentation is more of a household name than it was five years ago. I think the fact that more people want to remedy these challenges is brillant.”

Drain will be speaking FERMENTATION 2021 on “The Alt-Universe”

- Published in Business, Food & Flavor

How Important is Consumer Education?

This is the second in a series of articles that TFA will be releasing over the next few months, analyzing trends from our Member Survey.

Fermentation is cloaked in mystery for many consumers — it’s bubbly, slimy, stinky and not always Instagram ready.

So how can fermentation producers appeal to potential consumers? What’s the best way to share fermentation’s flavor and health attributes?

In The Fermentation Association’s membership survey on industry trends, a better-educated consumer was identified as a priority. When asked what would foster increased consumption of fermented foods and beverages, the top item for nearly 70% of producers was greater consumer understanding of fermentation and familiarity with the flavors associated with fermentation.

“More than wanting to sell a product, I want people to know the information,” says Sebastian Vargo of Vargo Brothers Ferments (who is speaking at FERMENTATION 2021). The Chicago-based brand sells ferments like pickles, sauces and kombucha. “I believe preventative health starts with fermentation. I’m explaining the difference between a pickle you see on the shelf versus a pickle you see in the refrigerator. But I’m also teaching people to power up their pantry, sauce up their life with condiments.”

Health vs. Flavor

Producers say they struggle sharing fermentation’s benefits with consumers. There are not enough peer-reviewed scientific studies on many fermented products to be the basis for health claims.

“We feel a responsibility as a fermented food company to entice customers into trying these hugely beneficial and delicious products,” says Savita Moynihan, who owns SavvyKraut in Brighton, UK, with her husband Stevo. But, “with sauerkraut, it is generally understood that raw and unpasteurised kraut is good for you but once you try to elaborate on live culture vs probiotics it gets complicated, more than it needs to be.”

Can a brand claim to include probiotics? Producers feel that guidance is not clear.

“There is confusion here that we feel needs to be ironed out in order to loosen the reins so fermenters can promote their products and their benefits with much more confidence,” she adds.

Moynihan says that, when SavvyKraut sells at farmers markets and local shops, they try to communicate two main things to consumers. First, the health benefits, like enhanced vitamin and nutrient contents, increased fiber and an aid to a diverse gut and digestive system. Second, the delicious flavor.

“The process of fermentation really enhances the flavours and creates an entirely new type of flavour which can elevate any meal,” Moynihan adds.

Lack of Tastings Hurting Efforts

One of the best ways to familiarize consumers with fermentation is for them to taste a product — flavor is a great marketing tool. But COVID-19 has hurt these efforts. Producers are unable to stage in-store demonstrations, offer samples at farmer’s markets or host in-person events. This has been especially hard for kombucha brewers, says Hannah Crum(who is also speaking at FERMENTATION 2021), president of Kombucha Brewers International (KBI).

“We still have such a big part of the population who don’t drink kombucha or don’t even know about [it]; we still have a lot of work in education,” Crum says.

Joshua Rood, CEO of Dr Hops Hard Kombucha, confirms, adding: “It continues to be very difficult to grow our brand and the whole category without live events.”

“The inability to do live tastings in 2020 had a significant diminishing impact on our sales during the pandemic,” he continues. “One of our main distinctions as a brand is superior taste. Consumers, however, do not believe claims about that unless they experience it for themselves. Even now we are significantly hampered by the lack of large beer festivals and street fairs. An artisanal craft brand like Dr Hops needs those live interactions!”

The Knowledge Gap

Despite the lack of in-store tastings, experts at New Hope Network (producers of the Natural Products Expos) say brands have a great opportunity — now, more than ever, during the COVID-19 pandemic — to connect with their consumers.

New Hope’s 2021 Changing Consumer Survey found U.S. consumers are not satisfied with their current health. Only 8% say they’re “extremely satisfied” with their health today, compared with 20% in 2017. Nearly 80% of consumers understand that diet greatly influences their health (79%). But achieving good health is both a goal and a struggle for consumers — and this is where brands can step in.

“There’s a gap to be bridged,” says Eric Pierce, vice president of business development for New Hope Network, during a session “Understanding Your Consumers” at the most recent Expo East. “I see it as our opportunity and our responsibility to help consumers translate healthy intentions into healthy behavior, either in how we’re educating them in our stores, the products that we’re innovating or the ways we’re communicating. Getting better at communicating can help them with solutions.”

A consistent, transparent, well-communicated message — from product label to social media page to website — is important. Pierce says consumers quickly see past “shallow marketing claims.”

“Leave a trail of breadcrumbs people can find,” Pierce advises. “You don’t have to communicate everything all at once, but allow people to follow a trail to the deeper story. When consumers want to find that trail, if it’s not there, they’ll quickly write you off as shallow with unbacked claims.”

Amanda Hartt, market research manager at New Hope, suggests putting a QR code on a product label that links to the science backing the benefits of your ingredients. Or partnering with a registered dietitian on social media to highlight how to use your product as part of a healthy diet.

[To learn more about this topic, register for FERMENTATION 2021 to hear one of the keynote panels “Educating Consumers About Fermentation.”]- Published in Business, Food & Flavor, Science