Brewers Using Yeast Strains Now for Bold Flavor

Hops used to be the biggest thing in beer to create a powerful flavor — now it’s yeast strains. Brewers are using yeast strains from around the globe for the best flavor.

According to the New York Times: “For some time, it’s been a hopped-up arms race as breweries regularly double or triple the amount of hops to create stronger aromas. With breweries using the same hops, many beers are starting to smell alike. … In search of distinct aromas, brewers are embracing yeast and bacteria strains from across the globe. They’re creating beers that let each type of microbe speak its unique language, and drinkers are listening.”

DeWayne Schaaf, owner of @ebbandflowfermentations Ebb & Flow Fermentations brewery in Missouri, calls himself a “yeast nerd.” He does not use commercial yeasts in his drinks, instead fermenting with yeast strains from Scandinavian farms, bottles of Spanish natural wine and Colorado dandelions. Few hops are required in his drinks as, during fermentation, the yeast converts sugars into alcohol for the flavors.

Other fermenters featured in the article include: @omegayeast Omega Yeast (supplier of yeast strains in Chicago), Berg’n (a beer hall in New York), @alvaradostreetbrewery Alvarado Street Brewery (brewery in California), @yeastofeden Yeast of Eden (brew pub in California), @bootlegbiology Bootleg Biology (yeast lab in Tennessee), @whitelabsyeast White Labs (yeast supplier in North Carolina and California) and Lars Marius Garshol (Norwegian author of “Historical Brewing Techniques: The Lost Art of Farmhouse Brewing

Read more (New York Times)

- Published in Business, Food & Flavor

Noma Reopens as Walk-In Burger, Wine Bar

The world’s most famous fermentation restaurant is serving diners once again during the coronavirus pandemic. But Noma’s reservation-only tables and $400-500 world-class meal has radically changed. Noma is now serving wine and burgers in a walk-up, outdoor patio.

“It’s definitely new territory,” says Rene Redzepi, Noma founder. “I like this thing that it’s doing to us. We’ve become this place where you book, you plan your travels six months ahead of time. The spontaneity of going to a restaurant has completely disappeared for us. I like that people now can say ‘Let’s go to Noma for a glass of wine.’ So who knows, maybe this is part of our future in the long run.”

Redzepi spoke with Denmark-based food bloggers Anders Husa and Kaitlin Orr on Noma’s reopening.

The Noma burger is either a meat patty made with beef ferment, beef garum and smoked beef fat or a veggie burger made with quinoa tempeh patty with fermentation liquids.

Noma’s Nordic cuisine features fermented and foraged food that have earned Noma the World’s Best Restaurant award four times. Noma has been closed since March 14 because of the coronavirus.

Redzepi is one of the first chefs of his caliber to reopen a fine-dining restaurant during the coronavirus pandemic. The burger and wine menu is intended to transition Noma to the July summer season, when the restaurant hopes to again serve diners in the restaurant.

When the coronavirus first shutdown countries all over the globe, Redzepi said “it was really, really scary.” Would Noma have to wait six months to open? A year? About 3-4 weeks in, though, the atmosphere turned.

“There was a little positivity coming through,” Redzepi said. “I started asking myself ‘What do I want to do? What am I missing in my life?’ And the funny thing is I wasn’t at all missing going to a fine-dining restaurant, sitting for 3-4 hours. That was not on my mind at first. I wanted to be with people, I want to be out. … So when you have that feeling, it was just like, there was no way we can open Noma as it was before COVID-19.”

It’s an unusual sight at the exclusive restaurant – Noma is serving burgers in paper wrappers and chefs are wearing disposable gloves.

A burger was picked because Redzepi says: “I have yet to meet anybody that doesn’t like a burger.” In the future, Noma will add a deep-fried chicken burger to the menu as well as oysters and shrimp.

As tourism is still closed in Denmark, Redzepi envisions the new Noma bar as a place where Copenhagen locals can eat and visit with friends again.

“It’s not about us showing what we can do, it’s just about cooking the best we can so people feel great and feel alive again.”

- Published in Business

Over 200 Breweries Release “Black is Beautiful” Collaborative Stout

Weathered Souls Brewing Co., a black-owned brewery in Texas, has launched the Black is Beautiful initiative to bring awareness to racial injustice and “show that the brewing community is an inclusive place for everyone of any color.” They are encouraging breweries to develop their own Black is Beautiful stout. Weathered Souls has shared a stout base recipe, and ask breweries to develop their own creative spin on the drink. A free label has been provided on their website, and the campaign encourages breweries to donate a portion of sales of the stout go to local foundations that support police reform and legal defenses.

Stout is a top-fermented beer that ranges in color from dark brown to almost black.

Marcus Baskerville, founder and head brewer at Weathered Souls, told the San Antonio Current: “The brewing industry is pretty eclectic, with all kinds of different people in it. Why wouldn’t this community be one to join together to support a message of equality and purpose to support the concept of general respect for everybody?”

Read more (San Antonio Current)

- Published in Business

Q&A with Author and Fermentation Expert

How to make fermentation practical for modern people? That’s a culinary goal Alex Lewin is passionate about reaching. Lewin is the author of “Real Food Fermentation” and “Kombucha, Kefir, and Beyond” (and member of TFA’s Advisory Board). His mission is “lowering barriers to fermentation.”

“Most of the ways we control the environment is lowering the barrier of fermentation for the microbes, like adding salt to the cabbage or keeping yogurt at the right temperature,” Lewin says. “But a lot of what I’m doing is lowering the barrier of fermentation for the humans.”

Lewin began fermenting as a hobby, and it turned into a passionate side career. Lewin works in the tech industry for his day job, then spends his spare time immersed in fermentation projects. His schedule parallels his interests. Lewin studied math at Harvard University, then studied cooking at the Cambridge School of Culinary Arts. He’s often tinkering with a microbe-rich condiment in the kitchen after office hours, and attending new fermentation conferences during his vacation time.

“Fermentation gives me direction in my life, but there’s also something about tech that nourishes me. And I don’t have to choose,” Lewin says. “The fermentation world, it is a huge amount of community. The community of fermenters really reflects the community of microbes. There’s some very interesting, very open-minded people who are outside of the mainstream in the fermentation world. And a lot of them feel they have a calling, that they were called to do this.”

Below, excerpts from a Q&A with Lewin from his home in California’s Bay Area:

The Fermentation Association: What got you first interested in fermentation?

Alex Lewin: I’d always been interested in food and started cooking a little in college. My dad had heart disease and later diabetes and he was on these diets and pills, but things didn’t seem to be getting him any better. When I got interested in health and nutrition during this time, I partly did it out of fear for my own life.

I started reading books about health, nutrition, diet, food. What struck me was they all said different things. I had studied math, physics, and generally the experts agree more or less on the obvious stuff. There’s discussion on the origin of the universe, yes, but no disagreement about what happens when you drop something and it hits the floor. I was surprised at the difference. One cookbook would say what would really matter in your health is your blood type — another would say the ratio from carbs to fat to protein that you eat, you have to eat them at a certain ratio at every meal. Then another book says don’t eat protein and carbs together, have space between them. I would read and was intrigued and frustrated. I had this idea that it should make sense and it didn’t make sense.

I was in a bookstore one day and I saw the book “The Revolution Will Not Be Microwaved” and thought it was such a fantastic title. It was about food politics and underground food movements and food subcultures. It was written by Sandor Katz and he writes with so much heart, very intelligently. He writes about radical food politics and has this way of keeping it very balanced and measured. Some books about radical politics can be shrill, but there’s nothing shrill or strident about anything Sandor does.

I wanted to read what else Sandor had written and found “Wild Fermentation,” and made my first jar of sauerkraut. In the meantime, there’s another book that affected me a lot, “Nourishing Traditions” by Sally Fallon. And that book similarly blew my mind. That book took all these diverse threads of diet, health and nutrition and pulled them all together in a way no other book has or has since. I felt like I finally understood what to eat, where before it was a free-for-all.

One of the things I learned to think about when you’re eating are foods with enzymes, microbes and live foods that weren’t processed with modern processing techniques. That really set me on my path.

TFA: After that, you spent the next decade diving into fermentation. You went to cooking school, started teaching fermentation classes, got involved with the Boston Public Market Association. How did your book “Real Food Fermentation” come about?

Lewin: A friend of mine who had a chocolate business recommended me to a book publisher. That was for “Real Food Fermentation,” my first book, in which I made it as easy as possible for people to ferment things. I knew from my class, making sauerkraut is not very complicated, and once people see it and how easy it is, they’re likely to keep doing it. So in my book, there are lots of pictures. There are lots of people with kitchen anxiety who are more comfortable if they see pictures of everything — pictures of me slicing the cabbage and putting it in the jar. I’m not a visual learner, I want to see words and measurements and numbers. So the book has both.

As time went on, I ended up meeting Raquel Guajardo (co-author for Lewin’s book “Kombucha, Kefir, and Beyond), and we decided to write a book about fermented drinks. I think it’s a great book because we both got a chance to share our ideas about food and health and what is happening in the world. Then we got to share recipes from my experience and her experience as a fermented drink producer in Mexico, where some of the pre-Hispanic traditions are very much alive.

Fermented drinks I think are also easier. They’re a little less weird to people than sauerkraut and kimchi, they’re less intimidating. We all drink things that are fizzy, sweet and sour. But like kimchi, it is so far outside of the usual experience of eating. Most people know they shouldn’t drink five Coca-Colas a day, so fermented drinks are the answer.

TFA: Tell me more about your goal to lower the barrier into fermentation.

Lewin: What is it about kombucha that is familiar? It’s fizzy, sweet and sour. What is soda? It’s fizzy, sweet and sour. I’m certainly not the first to observe that, but I’m connecting the dots on how we can integrate these ancient foods into our modern lives.

For me, I always considered myself an atheist. Then when I started fermenting, I started letting go and thinking there are things outside of our control and we just need to accept them. There are things we will never understand completely, there are forces we don’t even know about. I came to faith and spirituality through the practice of fermentation.

A lot of the problems that we face today have been created by application of high technology to the food system, then we try to solve them by using more food technology — like growing fake meat. The problems caused by high tech are not going to be solved by high tech, they’ll be solved by low tech. And fermentation is one of my favorite low tech technologies. You pretty much just need a knife.

Fermentation also gets away from the western, scientific, medical paradigm that’s so reductionist, where we’re looking for some small isolated problem in the body and then trying to counter it. Looking for some metabolic issue and trying to neutralize the symptoms. “Your blood pressure is high, let’s lower it with a pill.” If the underlying causes of all these things are eating bad food, trying to attack the symptoms one at a time is not the easiest way to make progress. We have to move away from this reductionist mindset where we’re playing whack-a-mole with our symptoms. We’re healthier looking for the underlying problems and addressing them.

Gut health is a big one. All sorts of other problems caused by high-tech, processed foods. Eastern medicine has more of an idea of holistic health, what’s going on in the system. I think that’s the future. I think a lot of the health problems will be solved through system-type thinking. This balance of energy. There’s a dynamic of equilibrium in our gut.

TFA: You mentioned Sandor Katz’ book “Wild Fermentation” introducing you to fermentation. What about his book appealed to you?

Lewin: There’s something rebellious about making food and leaving it out on the counter. I hadn’t been to cooking school yet at that point when I read it. But you read about food safety and there are rules, you can only leave food on the counter for so long at this temperature. There are all these things you’re not supposed to do with food. But in order to ferment, you have to violate these rules to grow the microbes. There’s something rebellious about fermentation.

Another part of it is the utterly low tech aspect to it. All the trouble we go to to process our food in high tech ways today, turns out we can do it better without preservatives, without heat packing things, without the refrigerator.

When you ferment something, every time it’s a little different. And you can keep doing it again and it doesn’t matter if it wasn’t perfect. And a lot of times you can do something interesting with it. I made pickles the other day, they turned out soft, so I’m going to make them into relish. Too much sourdough starter? Turn it into a porridge. Your kombucha got too sour? Turn it into vinegar. Sometimes something can be ruined, but often you can turn it into something else. Being able to make kombucha that’s better than most of the store-bought kombucha is pretty cool — I discovered that ability.

TFA: Why do you encourage people to incorporate fermented foods in their modern diet?

Lewin: One of them is just coming back to the kitchen. During the coronavirus pandemic, people are coming back to their kitchens. That’s an unqualifiedly good thing, it means that much less processed food and that much less fast food. Fermentation also brings people back into the kitchen. And fermentation is in the limelight during the pandemic. Especially sourdough right now. Fermented projects are great things to do with families, kids. When you talk to the older generation about making sourdough, pickles, bread, they have these stories. My mom never made pickles, but her father did. It’s not too late to get these stories. Food is one of the things that connects generations of people, that reminds us of our roots and grounds us, literally.

Making anything with your hands, it’s a cure for all sorts of things. Not even getting into physical, digestive health. Just making something and liking it is psychologically healthy. You feel empowered in the face of so many disempowering things. If you can turn cabbage into sauerkraut, you have power.

And then there are all the concrete, physical health benefits of eating fermented foods. You get more enzymes, more vitamins, more microbes, you get more of the good microbes and fewer of the bad microbes. You get probably less processed food, less sugar, you get all these trace substances that you really don’t get from processed food. Like nattokinase, which is this enzyme you only find in natto and might protect against heart disease and cancer. Depending on the ingredients you use when fermenting, if you use the right salt and right sweeteners, you can get minerals. Fermenting in some cases creates vitamins. You can straighten out a lot of digestive problems in my experience by introducing fermented foods, gradually.

TFA: You’ve watched Americans’ diets adapt (or not adapt) over the past few decades to changing health standards. How have Americans’ perception of fermented food and drink changed in that time?

Lewin: Americans are absolutely more accepting of it. The story of kombucha is a good one. You can follow annual kombucha sales. You used to say “kombucha” and people would say “Ew” or “What’s that?” or “My crazy aunt makes that.” Now, it’s a billion dollar business. You can get it in mainstream supermarkets in most of the country, it’s not a fringe thing anymore. Fermentation is coming to the mainstream. Kimchi is not a fringe thing. I think the rise of food culture, with food reality TV shows, has really helped fermented things like kimchi. When food trucks in LA started having kimchi and Korean BBQ tacos, for me I felt like something had turned the corner. The rise of microbreweries and the interest in natural wines and the movement away from like super-oaky chardonnays and ginormous reds to more natural wines. I think people are a lot more sophisticated about food than they were 20 years ago, and a lot of that is leading to increased interest in fermented foods.

Fermented foods are no longer fringe. We’ve come a long way in 20 years. Kombucha and kimchi are two of the flag bearers of fermentation. I think fermentation is on the rise. People will say “I think it’s just a fad,” and I’ll say “It’s absolutely not a fad.” People were fermenting 10,000 years ago. It never left. Every drop of alcohol you’re drinking, that’s fermented. It never went away, it was under the surface and now it’s on the surface again. People are just realizing it’s important.

TFA: Where do you see the future of the industry for fermented products?

Lewin: I think the more people ferment at home, the more people are going to want to buy fermented things. The more people ferment at home, the more they’ll appreciate fermented products and seek them out. It’s not like there’s a competition between home fermenting and commercial producers. If anything, there’s a symbiosis. I’ll make kimchi sometimes, but I’ll buy it sometimes, too, because it’s messy and there are people that make very good kimchi. Same with kombucha or high alcohol kombucha. I could make it if I wanted to, but it requires time and patience. Miso is another example, I don’t have the patience to wait six months to make miso.

- Published in Food & Flavor

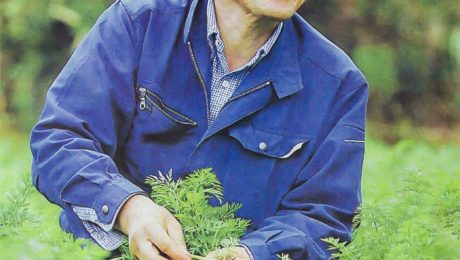

Farmer, Nutrition Activist Uses Fermentation Methods to Create Healthier School Lunches

An organic farmer and nutrition activist is teaching schools and daycare centers in Japan to grow their own vegetable garden using fermented compost from recycled food waste, then incorporate into school lunches those fresh vegetables with traditional Japanese fermented foods (like miso and pickles). Two years after the program’s launch, absences due to illness have dropped from an average of 5.4 days to 0.6 days per year.

Farmer Yoshida Toshimichi “is a devout believer in the power of microbes.” Using centuries of Japanese folks wisdom that is supported by modern science, Toshimichi explains that fermentation bacteria in the compost yields hardy, insect-resistance vegetables. He says the key to a healthy immune system is maintaining a diverse and balanced gut microbiota. “Lactobacilli and other friendly microbes found in naturally fermented foods can help maintain a healthy environment in the gut, just as they do in the soil,” continues the article. Microorganisms in fermented foods like miso and soy sauce will help balance gut flora. “Organic vegetables, meanwhile, provide the micronutrients and fiber on which those friendly bacteria thrive. In addition, phytochemicals found in vegetables—especially, fresh organic vegetables in season—are thought to guard against inflammation, which is associated with cancer and various chronic diseases,” the article reads.

Toshimichi has authored books on his farming and nutrition practices and is featured in the two-part documentary film “Itadakimasu,” which translates to “nourishment for the Japanese soul.”

Read more (Nippon)

- Published in Food & Flavor, Health, Science

Burma Superstar’s Signature Fermented Tea Leaf Salad

One of the signature dishes at the Burma Superstar Restaurant group in San Francisco is the fermented tea leaf salad, also known as “laphet thoke.” The fermented tea leaves come straight from Burma (Myanmar), a legacy important to Desmond Tan, founder and owner of the restaurant group. He worked for years to source organic, uncontaminated leaves, a major change to Burma’s tea leaf industry. Leaves were formerly notoriously tainted with clothing dyes and plagued with horrible trade practices. The tea leaves take 2-6 months to ferment, resulting in a uniquely sour leaf. Burma Superstar had made a natural tea leaf dressing to enhance the flavors of the tea leaf.

Read more (Forbes)

- Published in Food & Flavor

David Chang: “There’s a Good Chance Momofuku May Never Reopen Again”

In the weeks since the coronavirus pandemic forced restaurants around the world to remain open only for takeout or to close until stay-at-home restrictions are lifted, food icon David Chang has emerged as an advocate for the industry.

The founder of the Momofuku restaurant group says government intervention is desperately needed for food service to survive — without it, only big chains will remain. “I have a hard time seeing [smaller establishments and even chef-driven eateries] survive and making it through the end of this.”

“Telling restaurants they should close or only do delivery or just be 50% open was a death sentence,” Chang says. “And I think all restaurants would have happily have done so if we were given some type of safety net.”

The restaurant industry has suffered significant job losses since the outbreak of COVID-19. The Momofuku Group laid off 800 employees during the pandemic. According to the National Restaurant Association, 8 million restaurant employees have been laid off or furloughed.

Chang and Marguerite Mariscal, CEO of Momofuku group, shared their thoughts on what can be done to save the restaurant industry in Vice Media’s new “Shelter in Place series.”

“Right now, any small business owner in New York is put in a very precarious position where they either are closing, which means they can’t financially afford to pay their staff, or they’re trying to stay open to get any sort of income that will then allow them to keep people have,” Mariscal says.

Though restaurants have business interruption insurance, that only covers physical business damage. Restaurants can still remain open for takeout, but with great risks.

“I think we’re all looking for a little guidance,” Mariscal says. “If restaurants are going to be deemed an essential business, then treat it that way, right? Like, what are the protocols or safety procedures that we should be using to make sure that we’re operating in the, you know, safest, best light? But instead, you have business-to-business everyone making these calls. And I don’t think we feel were the best equipped to make them.”

Like who is regulating proper PPE use among restaurant workers? Should staff all be wearing gloves? Is a cloth mask good enough or should cooks wear a N95 mask? Where is the supply chain for restaurants to get this gear that wouldn’t hurt the medical supply chain? Chang says the lack of guidance from government leadership “it was so bad, it was embarrassing.”

“We need the state-level authorities, because it’s not going to happen from a federal level to say, ‘Hey, it’s dangerous to make food, in a COVID-19 world, this is what you need to do,’” he says. “There are a lot of people serving food in maybe not a safe situation.”

Government aid to help the restaurant industry is only short-sighted, Chang adds, because it’s not covering beyond summer. Unemployment will only cover a few months. There is no unemployment coverage for undocumented workers. Businesses can only receive money from the economic stimulus bill, CARES Act, if they rehire 100% of their workforce by June 30. Chang points to the aftermath of September 11 as an example. Restaurants closed for only a few days, but it took years for the New York tourism industry took years to recover.

The restaurants that will survive the pandemic will be large chain restaurants with big pocketbooks and corporate power – like McDonald’s and Taco Bell.

“That’s unfortunately the future that I feel we’re headed to unless we can have proper intervention and guidance and support and leadership from the government,” Chang says. “There’s a good chance Momofuku may never reopen again. Or the restaurant that you loved to go to so much in your neighborhood may never reopen again. If we don’t support the supply chain and the purveyors and the farmers and the workers all surrounding it, there may not be a new restaurant that’s going to be delicious, that’s going to have the vibrancy that you want, for a considerable amount of time. People are going to realize just how important the food industry is and the workers that have been neglected for so long, I think they’re going to realize, holy shit, we didn’t realize how much we depend on the food industry.”

What will restaurants look like, after the pandemic? Sanitation standards will be increased, there will be greater oversight from the FDA and CDC. But the future “is going to be predicated on something that we have no preparation for,” Chang says. Ghost kitchens, delivery and e-commerce will become the driving force of restaurants, operations most restaurants are not set-up to implement.

“What you’re going to see is maybe there’s less of a restaurant industry and it’s more of a food industry,” Mariscal says. “Everyone’s going to have to reimagine how they make money.”

Chang says big corporate, quick-service restaurants are prepared. Large chains “they’re never touching the food, it’s just an assembly process,” Chang says. Smaller restaurants, independent diners and even upscale chef-driven eateries rely on culinary touches, though. Chefs taste the food and experiment with dishes.

“It would be hard to live in that world where there isn’t variety,” Chang says. But “in terms of food, I think there’s going to be less choice.”

- Published in Business

The Science of Yeast, the Microbe in your Pandemic Bread

Humans have been baking fermented breads for at least 10,000 years, but commercial yeast and flour companies have never seen demand so high. National Geographic shares “a story for quarantined times, about extremely tiny organisms that do some of their best work by burping into uncooked dough.”

Scientists describe the microbes behind the work fermenting the bread. “It’s this wonderful living thing you’re working with,” says Anne Madden, a North Carolina State University adjunct biologist who studies microbes. She and partner scientists showed recently that when bakers in different locales use exactly the same ingredients for both starter and bread, their loaves come out smelling and tasting different. “Which I think is fantastic,” she says. “It’s evidence of the unseen. And as a microbiologist, you so rarely get to measure things about microbes with your nose and your taste buds.”

Read more (National Geographic)

- Published in Science

Bubbling Over: How to Prevent Mold in Sauerkraut

Three fermentation experts weigh in on one of the most common problems in fermenting vegetables: mold prevention. The fermenters include fermentation chef David Zilber (head of fermentation at Noma) and fermented sauerkraut producers Meg Chamberlain (co-owner of Fermenti Farm) and Courtlandt Jennings, (founder and CEO of Pickled Planet and TFA advisory board member).

How do you handle prevent mold in sauerkraut?

David Zilber, Noma: That is something you are constantly trying to fight back, especially when you lacto-ferment in something like a crock. There are so many variables that go into making a successful ferment. How clean was your vessel before you put the food in there? How clean were your hands, your utensils? How much salt did you use? How old was the cabbage you were even trying to ferment in the first place? Every little detail is basically another variable in the equation that leads to a fermented product being amazing or terrible. It’s a little bit like chaos theory, it’s a little bit like a butterfly flapping its wings in Thailand and causing a tornado in Ohio. But with lots of practice, you’ll begin to understand that, if it was 30 degrees that day, maybe things were getting a little too active, maybe the fermentation was happening a little bit too quickly. Maybe I opened it a couple times more than I should of and it was open to the air instead of being covered. So there’s lots of variables. But I would say that, if you’re having a lot of trouble with mold, just up the salt percentage by a couple percent. It will make for a saltier sauerkraut, but it will actually help to keep those microbes at bay. (Science Friday)

Meg Chamberlain, Fermenti Farm: You must allow the ferment to thrive by creating a favorable environment with “Good Kitchen Practices.” So, to prevent mold in your ferment start by using only purified water, like reverse osmosis, distilled or boiled and cooled and-no tap water(municipal). Only use vegetable-based soap that is NOT anti-bacterial, like a good castile soap. Finally, only use dry fine Sea Salt, no mineral/no gourmet or iodized. Keep Fermenting and do not get discouraged! #youcanfermentthat #diyfermentation #idfermentthat

Courtlandt Jennings, Pickled Planet: Preventing mold when making sauerkraut is all about a controlled atmosphere. How well you maintain your situational cleanliness and fermenting atmosphere is my best clue for you. There are many ways to control atmosphere and every situation will be different based on many factors but be dillegent and your ferments will improve with practice.

This may not seem like an answer but it’s directional… as is most advice unless dealing with a consultant. Good luck and may the ferment force be with you!

- Published in Food & Flavor, Science