Fermenting Wild Food

Master forager Pascal Baudar shares insight from research for his new book, “Wildcrafted Fermentation: Exploring, Transforming, and Preserving the Wild Flavors of Your Local Terroir.” He believes more people should live off the land. He tells Modern Farmer: “Lacto fermentation really started to create a new level of dealing with wild plants and understanding how to get those wild plants from a culinary perspective.”

Read more (Modern Farmer)

- Published in Food & Flavor

Rebecca Wood on the Delicious Taste of Fermented Foods

“Why do some foods like chocolate, wine and cheese taste so delicious? Fermenting magically transforms their original ingredients into something more desirable. Besides upping flavor, some lactic-acid ferments, such as homemade sauerkraut, actually strengthen your immune system.”

Rebecca Wood, “Fermented Foods Strengthen Immune System“

- Published in Food & Flavor

India’s Rich Pickling History Kept Alive by India’s “Pickle Queen”

“I just want everyone to understand the depths of Indian cookery,” says Usha Prabakaran, author of the 20-year-old cookbook “Usha’s Pickle Digest.” The New York Times published the fascinating story behind the woman known as India’s Pickle Queen. Her self published book is a cult classic today, highlighting India’s rich history with pickling and fermenting. “ India’s pickle culture goes back thousands of years to when cucumbers and other vegetables were simply preserved in salt. Modern Indian pickles are more complex and probably more delicious, too — hot and tangy, deeply perfumed with aromatics and ground spices.”

Read more (The New York Times)

- Published in Food & Flavor

David Rains Wallace: “Fermentation may have been a greater discovery than fire.”

- Published in Food & Flavor

Exploring Flavor Space with David Zilber & Jason White

Fermentation opens a culinary Pandora’s Box says David Zilber, head of fermentation at Noma restaurant in Denmark. Instead of just pureeing or heating a berry, the berry can be juiced for alcohol, transformed into vinegar, preserved for a fish sauce, pickled or dehydrated.

“Fermentation was a discovery of possibility,” said Zilber. “You see the recommitorial power that comes from fermentation. It’s not just a subset of cuisine in gastronomy, it’s honest to goodness as large or it not larger than the world of gastronomy itself.”

Experimenting with ingredients that lead to tasteful outcomes is why “fermentation is so thrilling to explore” Zilber told Harvard students at Harvard University’s Science and Cooking Lecture Series. Zilber lectured with former Noma colleague Jason White, head of research and development at the Kudzu Complex in Tennessee.

Experimenting in the Noma Kitchen

Their topic: “Exploring Flavor Space: Innovation through Tradition in Noma’s Fermentation Lab.” The two shared fascinating insight into Noma, the two-Michelin-star restaurant regarded as one of the best in the world. But how do cooks toy with fermentation when the Michelin guide historically values consistency? Thousands of experiments and variations. Only 5% of what the chefs in Noma’s fermentation lab creates make it onto a plate.

“If you’re not trying to keep things traditional, you’re free to do whatever you want. And that’s the beauty of fermentation for us,” Zilber said. “When Noma employs fermentation, we do it knowing that we can change things. That we can seek out flavors by looking to old techniques, by turning to tradition, breaking down processes via reduction, pulling them apart, saying what enzymes are at play? What molecules are in the mix? What byproducts can be produced?”

Zilber showed the huge shared file between Noma employees of recipe trials. Things like moose snout, moldy vegetables, roasted pinecone, egg picked in elderberry juice and pig meat fermenting in its own pancreas enzyme. One of Noma’s early successes was adding a few drops of a fish sauce to a dish. A few drops of a potent fish sauce iteration goes a long way when flavoring a meal. The cooks began creating fish sauce equivalents, like a fish sauce from squirrel, sea cucumber, beaver, sea star, reindeer, wild boar, razor clam, bear (“That was the worst thing we’ve ever tasted,” Zilber said, “that did not go right.”).

“These were huge discoveries for us at Noma because, all of sudden, you could have a primarily vegetarian cuisine that had all the flavor and impact of like a full plate of food with meat and starch and vegetables just by using seasonings,” Zilber said. “And kind of flipping the role of meat and vegetables on its head. Suddenly vegetables didn’t have to be the accoutrement that just served to kind of temper what you were chewing in your mouth and act as the texture. They were actually the starring role, but you were as satisfied as eating a full plate of sliced sirloin because you could have this taste of meat permeating through your samphire mixed with watercress emulsion.”

Fermentation is the most useful tool for the restaurant, Zilber said. Noma has what he calls a “DIY or die” attitude.

When Noma chef and co-owner Rene Redzepi opened the restaurant in 2003, he wanted to create a fine-dining experience concentrating on the food of the Nordic region. Fine dining in Denmark, Sweden and Norway was primarily French food because the cold, coastal Scandinavian countries have such a short growing season. Redzepi and the cooks dove into cultural recipes. They contacted local foragers, then experimenting preserving the ingredients they’d find. They started a Noma Food Lab to catalog the different ingredients.

“When you taste all the products of fermentation, you understand it is delicious because it is that heightened level of food. All life is transformation – creation and destruction are just two sides of the same coin. Building things up in a certain way is just half of the picture if you understand you have to break them down first. And when your body understands that something has been broken down for it in a friendly manner by something that isn’t harmful in any way, alarm bells go off and you understand these things to be delicious.”

“That search for that flavor…is how Rene and the team back in the test kitchen in those early days learned to use the very paltry pantry that sat at Noma’s disposal with all these Scandinavian ingredients and multiple them many times over w the dimensionality of flavor that fermentation could provide. If at first, they only had in a season 250 ingredients to work with, they could turn to fermentation and all the different processes at their disposal to turn those 250 into 1,000.”

During the Harvard lecture, White made a koji and miso for the students to sample. He detailed creating miso from unconventional protein-rich foods, like seeds, roots, parsnip, corn, fava beans, byproducts from oil extracted from nuts.

Transformation through Fermentation

“A field is a field and a plant is a plant. It’s only a weed if you choose to pull it out. But it’s a crop if you put it there and want to harvest it at the end. That’s exactly how you have to think about fermentation,” said Zilber.

Zilber said the technical, chemical definition for fermentation is the anaerobic, enzymatic pathway that yeast uses to metabolize glucose and transform that into alcohol in the absence of oxygen. Simply put, it is the transformation of one food into another by a microbe. But those definitions don’t go far enough to describe fermentation’s complexity.

“If you want to get really into it, you do have to talk about human intent,” he says. “And humans have a big part to play in fermentation because, without the human willing the fermentation into existence, you just have a free-for-all.”

Zilber uses the analogy that a fermenter is like a bouncer at a night club. The fermenter has to decide between the troublemakers and the enjoyable customers. Who is going to come in and start a bar fight and who is going to come in and order drinks and mingle with other customers?

“The club is all the food you’re looking to ferment, the ingredients you’re looking to transform, and which microbes to keep out,” he said. “The key to cooking with microbes is cooking with life. You need to keep these creatures alive so they do the cooking for you.”

Control points are key to a fermentation. Lactic acid – the metabolic process that converts sugar and glucose into energy – has five basic needs. Access to oxygen, salt concentration, pH levels, nutrient sources and temperature. Every control point and process will lead to a different fermentation outcome.

“You’re trying to build an environment for that microbe to survive,” Zilber added.

Harmful pathogens won’t grow in a controlled fermentation environment. Mold can’t live without oxygen. And botulism has a higher water activity level than lactobacillus, and water activity level drops once salt is added in fermentation.

“You’re cutting off at the pass any malevolent microbes that you think might grow,” he said.

Humans, he said, have domesticated the lactobacillus bacteria.

Use Tradition to Apply Fermentation Processes

Zilber knows fermentation is a trendy topic today, but he notes it’s been around since the dawn of man.

“The first real food technology we had for safe food preservation before the USDA was a thing was fermentation,” he said. “And it makes sense that we do it until this day and we have all these traditional recipes on our counter tops because these are things that have kept civilization alive for a very, very long time. And we have grown up to actually love the taste of them and understand them as part of our cultural history.”

Before recipes were shared through the internet, cultures passed recipes through families. Fermentation was mastered because because a grandparent taught it to a grandchild. This is why towns in Italy have a sausage (Genoa, Calabrese) and towns in Japan have a Miso variety (Hatcho, Saikyo).

Cooking your own fermented product “is about crafting those environments that your microbes need to thrive.” Making a koji is recreating the ancestral field in humid China.

Noma is revolutionizing fermentation by using using traditional processes, then creating their own techniques. Noma uses biological and mechanical technology in their food to push the boundaries of cuisine.

“Noma applies the basic concepts of fermentation, of preservation, of making something last in a season where it normally wouldn’t be available, but taking it to the nth degree,” Zilber said. “No, it’s not always about combining flavors and seeing which is the best. Sometimes it’s combining technologies and seeing what produces the best flavor. We try all different sorts of extraction, sonication, vacuum filtration, the (supercritical fluid extraction systems) unit.”

Partnering with local Denmark bio-tech firms, Noma uses scientific technology to explore different fermentation projects.

- Published in Food & Flavor

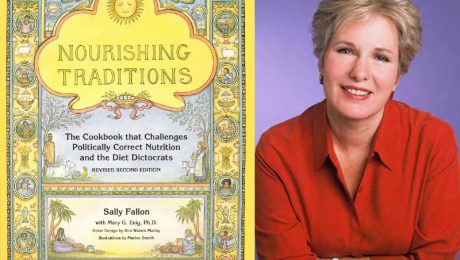

Sally Fallon Talks Fermentation

If just 10% of the population chooses to eat fermented foods, could the food industry be disrupted? Fermentation guru Sally Fallon says: absolutely.

“With fermented foods, you could get rid of all this huge medical industry selling you antacids and digestive aids, and this huge industry that’s grown up around IBS and celiac disease. We can destroy that industry by eating the right foods, and that means eating fermented foods,” Fallon says. The author of cookbook and nutrition guide “Nourishing Traditions” is often credited with bringing ancestral diet methods back into vogue.

Fallon, president of the Weston A. Price Foundation, founder of A Campaign for Real Milk and author of the new book “Nourishing Diets,” discussed fermentation during The Fermentation Summit. Below, selected highlights from Fallon’s interview with Paul Seelhorst, host of the summit.

Seelhorst: Tell us more about yourself and how you got into the fermentation topic.

Fallon: Well, when I was writing “Nourishing Traditions,” I wanted to make sure I was really describing traditional diets and not something people just think they are. I was very fortunate to find a book in French about fermented foods. I had never read about these before, lacto-fermented foods.

Recipes were very complicated – keep them at certain temperature for this many hours, then switch temperature for another few hours.

I kind of took this principle and worked out a way that was easy and fool-proof, using glass jars, we use way of innocuous so they don’t go bad while they’re starting to ferment.

Tried all these recipes, experiments, made children try – kids have funny stories about trying all these

The neat thing about fermentation is that it is a practice that’s traditional. When you ask traditional people why they do this, they wouldn’t know what to say or how to answer you, they just do it. But it totally accords to modern science. We have seen a complete paradigm shift in the last 20 years. In the past, bacteria were evil and they attacked us and made us sick. Now we realize that bacteria are our best friends, and we need at least 6 pounds of bacteria lining our guts in order to be healthy.

The way traditional people made sure that they had plenty of this good bacteria restocking everyday was to eat these raw fermented foods full of this healthy bacteria. They ate them in small amounts with the rest of their meals. This is how they did it, they had really healthy guts. We know when you have a healthy gut, everything goes better in life. You feel better, you digest better, you have more energy.

I recently wrote this book called “Nourishing Diets” which is about diets all over the world and what really struck me was the fermented foods. Every single culture in the world without exception eats fermented foods. Now some of these foods are pretty weird – like fermented seal flippers. Africa is the land of fermented foods. Almost everything they eat in traditional culture is fermented in Africa. They’ll kill an animals and ferment every part of the animal — the blood, the bones, the hoofs, the skin, the organ meats, the fat, the urine. Everything is fermented when they kill an animal.

Seelhorst: That’s pretty easy because its warm?

Fallon: Its warm, the bacteria like it. They have a saying – a rich man needs 10 animals to feed the wedding feast because he feeds everything fresh, but a poor man can feed the same feast with one animals because he ferments everything

Seelhorst: Do you know what they make out of urine, like a probiotic lemonade?

Fallon: I don’t know, they didn’t say. There’s two wonderful books on fermented foods – one is the “Handbook on Indigenous Fermented Foods” by Keith Steinkraus. He was at Cornell and is retired now. I fortunately talked to him while I was working on “Nourishing Traditions” and what he shows, he has a bunch of students from all over the world, especially Africa, and they do studies on the food. For example they take a food like cabbage and they’d measure the Vitamin c and the amino acids then they’d ferment it and measure it again. The vitamins goes way up – some 10-fold increase – and the amino acid increase.”

The other thing fermentation does with grains and meats, it releasees the minerals so they’re easily available.

There’s another wonderful book called “The Indigenous Fermented Foods of the Sudan: A Study in African Food and Nutrition.” The author was a student of Dr. Steinkraus. He reminds me a lot of Weston Price – he’s going to these traditional people not to, you know, lord over them and tell them how superior Western culture is. He goes with hat in hand saying “You guys have the secret here. You know how to eat; you know how to prepare food. Not only that, these foods can be done at the homestead, they can be taken to the market and sold, they are a good income for millions of people.” So he’s not pushing the industrial system, he’s pushing artisan food.” I just thought what a wonderful man, how humble. That’s how we need to come to these traditions – not how to make millions of dollars on them, but how to make a decent living for thousands of people and provide a healthy food for millions of people.”

Seelhorst: What I also like about fermentation is the sustainability aspect. People can make food sustainability and do not need fridges to keep the food good and not get it moldy.

Fallon: Foods like grains are impossible for humans to digest unless they are fermented. So many people can’t do grains, they’re sensitive to gluten. But when you ferment, as in the case of a sourdough bread or soaking your oats or pressed cakes all over the Southeast and Africa, these are fermented grains pressed into biscuits, this takes a food where most of the nutrients are unavailable to us and makes it readily available.

Seelhorst: Nowadays, people have fancy equipment to

ferment food. How did people ferment food back in the day?

Fallon: Usually they did it in large terracotta pots. And the culture was sort of in the holes of the pots, they didn’t have to add a culture, it was just hanging out there. When I started this in the late 1990s, this book I read in French was talking about these big pots. You couldn’t get these pots in the states when I was writing this book. I thought this isn’t going to work, the pots are heavy they’re expensive and they make a very large quantity which you may not be able to use. I thought we need a different method for the modern house wife or modern father. I thought “Let’s try to do this in Mason jars, the big quart jars with the wide top. Instead of having the culture hanging out in the holes, we didn’t have that. You had to add something in your culture, so that’s where we came up with adding whey. You have your cabbage or pickle or carrots or whatever it is you want to ferment, you put them in a bowl, you toss them with salt and a little bit of whey. You toss them, pound them a little bit, push them in the jar, push down heavily so the liquid comes and covers the top, this is an anerobic fermentation. Leave it at room temperature for a few days and its done.

Seelhorst: Where do people get the whey from?

Fallon: We teach people how to make it. You start with yogurt or with raw milk or something fermented like yogurt or kefir and you poor it through a fine cloth and the whey will drip out. From a quart of yogurt, you get about two and a half cups of whey. You’re only using a little bit at a time – a tablespoon or two – so that will keep a long time in the fridge. That’s your culture. There are other cultures, too. People are selling powders in culture. The only thing I would warn you is don’t try to do this without salt. Because the only time I heard about someone getting sick from fermented foods is when they didn’t use salt.

Seelhorst: Simply put – what happens during fermentation.

Fallon: What happens during fermentation is lactic acid is created by the fermentation. And in some foods, the lactic acid is already there. Like cabbage, cabbage juice is full of lactic acid. This makes whatever you’re fermenting get sour, it lowers the pH to under 4 and no pathogens can exist at a pH under 4. It makes the foods very safe and they don’t spoil after that. Lactic acid is a preservative just like alcohol is a preservative, but lactic acid doesn’t make you drunk. So, at the same time, these bacteria that are fermenting in there, they’re creating vitamins. Vitamin C, b vitamins. They’re breaking down what we call anti nutrients that block the simulation of minerals. They’re creating digestive enzymes that help you digest your food. The interesting thing is these bacteria and these enzymes do get through the stomach, they do get through and are passed into the small intestines where they are really useful. We’re not sure how that happens, they’re buffered in some way, but we do know these bacteria do get through

Seelhorst: How do you think fermented foods can fit into a modern diet.

Fallon: You can include them every day. One of my favorites foods is a fermented beet juice, I first noticed it in Germany, it’s called beet kvass. I have that every morning for breakfast. Sauerkraut is a really easy way, that’s the way most people do it, they just have sauerkraut with their meal. And then the fermented dairy foods like yogurt or kefir, those are wonderful fermented foods. You have a little bit with every meal.

Seelhorst: Are those the oldest fermented foods that we ate?

Fallon: In Europe, yes. We don’t have a tradition of eating fermented bones or fermented blood. But we definitely had fermented vegetables like sauerkraut, that dates to Roman times at least. And also fermented fish, the fish sauce, the universal seasoning, they found it in the ruins of Pompei where they were making it.

Seelhorst: What’s the difference between industrialized and self-made fermented food.

Fallon: once you industrialize something, they start to take shortcuts because they want to lower the cost. Typically, what they’ll do is eat something. So they’ll heat the sauerkraut and package it in plastic bags or something horrible or they’ll can it. So it will last forever and be shelf stable. Typically, the industry has not done genuine fermented foods because its not something that lends itself to an industrialized process. The things we consider true fermented foods in the united states, they’re being made by small companies.

Now the one exception to that might be yogurt. Yogurt is big business, it’s made by the big conglomerates. I would never even eat that yogurt because apparently the cultures are not even any good and the milk has been pasteurized.

Seelhorst: What’s your favorite fermented food.

Fallon: Kombucha. I make my own kombucha. I have a 30-day kombucha, I call it kombucha like fine champagne. It gets these tiny, tiny bubbles in it, it gets really, really sour and a little thick. I also make sauerkraut. It’s interesting – I’m a lot busier than I was when I wrote my book, I don’t have as much time as I used to have, but I still make my own fermented food. I do carrots and cabbage, I’m just about to pull some carrots and make some fermented cabbage.

I forgot to mention cheese. And cheese. Cheese is a fermented food. Here on our farm, we make cheese. I’d have to say cheese is my favorite fermented food. And also, traditionally made salami. A charcuterie is fermented. They hung these sausages up and fermented them. So they are fermented foods, they’re full of bacteria, good bacteria. They should be kind of sour, they’re very good for you.

Seelhorst: Do you want to add anything for people that just found the Fermentation Summit and may not know what fermentation is, they want to try it

Fallon: I will say this – you don’t have to make it yourself, there’s a lot available, in the states there’s now hundreds of artisan producers making sauerkraut. I love to see that – I love to seen an individual be able to start a little business without a big capital investment and make food that’s really good for people and make a decent living. Here on our farm, we have a store and we sell sauerkraut made by a Russian lady who has just made a wonderful living doing this. I love to see that. Just like artisan cheese. I love see small production of cheese; I love small production of fermented goods. Bread is another one, we now have a lot of artisan bread makers. This is the future of food – its sustainable food, its moral food, its food that makes you healthy, its good for the economy, it keeps the money in your community. I think people need to realize that every morsel of food they put in their mouth is a political act. It’s a decision they make. What are you going to support? Are you going to support Monsanto and Kraft and Unilever? These huge corporations who don’t care about you at all, all they care about is making a profit. Or are you going to support local artisan producers? People just like you making a decent living and providing a healthy food. And you’re also deciding whether you’re going to put something healthy or unhealthy in your body and in your children’s bodies. The traditional cultures, they had no choices in what they ate. They ate what was there, they ate according to their traditions. Today, we are not traditional people. We have left all that behind. We have to think what we eat, everything we eat is a choice. They didn’t have a choice, they just had healthy food. Now we always have this choice between healthy artisan food and unhealthy corporate food. So what kind of society do you want to live in?

- Published in Food & Flavor, Health

Q&A with Alex Corsini, Founder of a Sourdough Story

Ready-bake and frozen pizza is a market with little disruption. Processed ingredients, chemical-filled cheese and cardboard-like dough are the mainstay of a grocery store pizza.

But Alex Corsini wants to change that. After battling an autoimmune disease, quitting his rat race job in the tech industry and completing an apprenticeship at a Michelin-star restaurant, Corsini wondered why there wasn’t a delicious sourdough pizza in a consumer packaged goods brand. He started Sourdough Story in 2018 as the first USDA organic and Non GMO Verified pizza on the market.

“We wanted to hone in on ultra-thoughtful sourcing and really meticulous preparation, and celebrate slow sourdough fermentation” Corsini said. “I think there’s a lot of dogma in nutrition, and I want people to listen to their own bodies and also think about the roots of where their food is coming from. Pizza is an interesting canvas and platform to showcase this narrative and perspective.”

Below, a Q&A with Corsini, who believes food — especially fermented food — “is the foundation of healthy people.”

Q: Why did you start Sourdough Story?

Around 2016, I was working in the technology industry in startups. I developed this autoimmune condition out of nowhere. My doctors didn’t really have a name for what I was going through, they kept testing me and concluded this was something I’ll have for the rest of my life. I decided to turn to nutrition to mitigate symptoms. I read about the Whole 30 Diet and basically cut out every major allergen. I did it for 60 days, and all my symptoms went away. It was really powerful for me to overcome this through food and not really any medication at all.

Eventually, I started slowly adding back in foods. I started reading about wheat and the ancestral diet. My ancestors are from Sweden, and fermented dairy and sourdough is big there. I started baking sourdough and, the first loaf I ever made, me and my roommates just devoured the whole thing in minutes. And we still felt really good.

I had this epiphany that this whole anti-gluten movement I fell into, there’s definitely valid signs, some people have Celiac Disease. Some people can’t digest wheat as well as others. But there’s also this layer of dogma that I’ve succumbed to. Maybe this is about the ingredients and preparation than the reductive nutrition side of things that’s all too common in the media.

I started getting obsessed with sourdough baking. I decided I didn’t want to go back to the tech industry. I applied to sourdough bakeries and Michelin rated restaurants that focus on sourdough baking. I got an apprenticeship at Kadeau in Copenhagen and I literally walked into my tech job the next day and quit. I said I’m done with technology and I want to focus on food.

I spent a month apprenticing, learning about fermentation and the farm-to-table movement. Copenhagen is this booming food scene. There’s this identity and really strong sense in bakeries around California — it was even greater in Copenhagen. I had this realization — why is there not a sourdough pizza in a consumer packaged food brand? And why is there not a brand focused on sourdough as a general concept?

My whole thing was, let’s create a brand around sourdough. We started with pizza, but it’s a broad category. When I decided to do a CPG concept, I talked to the founder of my favorite natural food store in Sausalito. I asked to stock or work in product and get a sense of the retail store environment. I spent three months working in the grocery department, stocking at a natural food store. I told them about my sourdough pizza concept and asked if I could put a couple pizzas on the shelf and see how they sold. We have this idea of what our movement would be — we’d vacuum-seal pizza, we’d put them on the shelf in the deli section, people could take and back. We put out 12 pizzas, and in a few hours they were gone. The orders started getting bigger and bigger from there.

We officially launched in June 2018, making 50-70 pizzas a week for that location alone. We were written up in the local independent journal, and it started a domino effect. Now we’re in about 100 stores in the Bay Area and just throttling growth. We’re at the point where we’re ready to make a big footprint.

Q: You said when you were learning how important fermentation is to people’s diets, that pizza is a great platform to showcase that. Why?

My initial idea, going back to working at the Michelin star restaurant, I loved the idea of knowing where every ingredient came from. I love going to a customer with the menu and saying “This butter is from a grass-fed cow, its name is Mike.” Having that level of granularity was really important to me. With pizza, there are so many ingredients that make up pizza. It’s also a great creative product. It’s a product everyone is familiar with and everyone is passionate about it. If you ask somebody what their favorite type of crust is, you’ll get lots of different answers. They’ll fight you on their favorite pizza place in New York. They all have a favorite topping. It’s a passion product.

Our toppings, the tomato is the best organic tomatoes in the U.S. from DiNapoli, an hour away from us in California. Our flour is freshly milled flour by Central Milling Organics, an old family mill based out of Northern California. The cheese is from grass-fed cows from the Rumiano pasture, the oldest family-owned California dairy. I love the idea of partnering and showcasing with these companies, being on a first-name basis. Pizza is a great vehicle for that.

Q: Why is modern bread bad for the gut? What’s better about sourdough?

We think of modern bread making, conventional bread is a process of simply leavening bread, giving rise to the dough. They all use the same commercially manufactured yeast that was derived from a lab back in the late 1800s. The whole concept around this was to mass produce bread to make sure you can create an industrial product that you can scale to consistency. Before that, it was all sourdough-based bread products, dating back to ancient Egypt.

Sourdough is a process of not only leavening bread but acidifying bread. The key benefits come from the acidification. So you’re getting benefits like a lower glycemic index, more available vitamins and minerals from grain, some people think it’s easier to digest and you’re getting better preservation. The higher the acidity, the lower the propensity for bacteria or mold to affect the product.

The science of it — it mainly comes down to phytic acid, which is an organic, indigestible compound that all grains and seeds possess.

Unfortunately, humans don’t have the enzyme to break it down — it’s called phytase. Some animals have this, and can eat raw grains and nuts and benefit. So when we eat grain in modern bread today, there’s a ton of potential nutrients that we’re not absorbing. There are two primary ways of breaking this down. One way to break this down would be sprouting the bread, one would be sourdough fermentation. Lactic acid fermentation and the acidification process of sourdough, you are breaking down fidic acid. There are studies that show you can get up to 90% percent of the available nutrients in the dough, whereas conventional bread would get like 20%, according to clinical trials.

A lot of the indigestibility of bread is around phytic acid, but gluten is coming to the mainstream, it’s become the easy thing to blame.

It’s great to be able to say, with clinical backing, there’s more bio nutrients in sourdough. That’s powerful. What we’re trying to do now is be the first party and authority on validating the science around lactic acid fermentation. There really hasn’t been an interested party or corporation interested in investing in the science. Our goal is to work with these scientists.

Q: How do you ferment your sourdough?

Modern bread, industrial bread or pizza on the shelf, you probably see an hour to three hours of fermentation time. With us, we do a full three days of fermentation time. We constantly have this starter, this mother culture, that we feed twice a day. We slowly mix our batches, low and slow. We do a bunch of small batches rather than one large batch, we find we get better quality that way. We do a really slow batch, then we take our dough and ferment it in a proofing room for two full days and nights. It will vary a little bit, but each ferment goes above 70 hour.

We use 100% organic flour from Central Milling. The better the flour, the more microbial activity in the flour. We use a specific flour that’s grown three hours away in california, there’s a lot of whole grain in the flour. So the microbial activity is really active. What you get is a really healthy ferment with more lactic acid, so you get that classic sourdough tang and that’s what we’re going for.

Q: The flour seems really critical in fermentation to create a good dough.

It’s one of the important elements. You could have a company that says “We’re organic sourdough,” but they could be using terrible bleached flour and putting vinegar in it to make it taste sour, there are so many shortcuts.

Q: Tell me about the sourdough starter you use to create your dough.

For the starter, we use a local whole wheat starter and triple filtered water. Good water is super important with any ferment. We feed our starter local whole wheat, but our starter is decades old. It’s an heirloom starter from a natural foods business out here in Fairfax, California. It could be over 100 years old, we’re not sure. Feeding the starter is a constant point of stress. There’s a reason people mass manufacture bread, let’s put it that way. It’s like having a pet.

Q: What is the most challenging part of fermenting sourdough?

All the variables. It’s similar to any fermentation, where you need to measure the time and temperature. One thing that’s especially challenging is making estimates based on the temperature of the room and the seasonality. Thankfully we’re in San Francisco, so it’s not dramatic, but sometimes we’ll get a heat wave and it will change the dynamics of our operation, we’ll have to make adjustments on the fly.

Q: What flavor difference does sourdough bring to pizza?

The biggest difference is that, with any baked good with conventional yeast, you’re going to taste yeast. It’s a very distinct taste. Our sourdough specifically, what you’re going to taste is something that’s a little more nourishing and wholesome. You’re doing to get a little bit of the whole grain but not too much, it doesn’t taste like a whole-grain pizza. It’s something more artisan. You’re going to get a finish that’s slightly acidic, enough that you want to take another bite. It’s addicting — it makes you salivate. With any ferment, there’s this metabolic process where you’re salivating more, you’re wanting more, it’s your instinct.

Q: Sourdough Story was the first USDA organic and Non GMO verified pizza on the market. Why was that important to you to get those certifications?

This was a point of contention. Just because industrial organics and the fact that having this certifications does not inherently validate that you’re a thoughtful brand. The reason I would argue it was the right decision is it creates immediate consumer trust, and puts us in channels that we want to grow into quickly, whether its natural or conventional. It gives us a point of differentiation against brands that aren’t thoughtful at all. It helps us with our sales funnel, and through the sales process being able to go to buyers and check the box. It also gives us leverage in closing new accounts.

For consumers, if anything, having both shows we’ve done our due diligence and we’ve been vetted. Overarchingly, I think it was the right decision.

Q: Is there a lot of competition from the gluten-free market?

My whole thing is that, whether you’re gluten free or not, at the end of the day, people want to feel good about eating pizza. We’re providing people an avenue to feel good about eating pizza.

There’s so many new entrants in the gluten-free space. What really bugs me about gluten-free products is a lot of them don’t care how they’re sourcing their ingredients. They’ll get terrible rice flours you don’t even know where they’re coming from, or cauliflower from international markets, or processed cheeses making up crusts. Our thing: we’re going with tradition. We’re going to trust the heirloom staples, sourdough being one of them, that’s been around for thousands of years, that’s touching every culture. I think it’s good for us to be different.

Q: Where is your copacker, are they in Northern California?

Yes, they’re in Berkeley. It’s a copacker made up of artisan pizzaiolo from Italy. Every pizza is handmade and hand stretched. It’s a USDA organic facility. It’s only us and then their line of organic products. It’s a special little manufacturing facility.

Q: More and more retail news shows fermented pizza dough is an increasing trend. Why do you think so?

If I had to say one thing I’d start with flavor. You win people on taste. And I don’t think there’s anyway a modern bread can taste better than sourdough. The reason being it’s pure umami flavor. If you ferment dough correctly, you’re going to get this incredible flavor that’s unmimicked by conventional applications.

Q: Where do you see the future of Sourdough Story?

We want to have a national footprint in natural and conventional. More importantly, we want to be the authority for all things sourdough based. We want to provide research, we want to provide recipes and information on how to get people involved in traditional baking, we want to be the point on all things sourdough based, and really creating a category for it. And we see the brand expanding beyond pizza in the future, too.

Q: Do you think consumers awareness of fermented foods is increasing?

Wholeheartedly, yes. Almost all my friends have jars of kraut in their fridge now. The whole microbiome, all the understanding and science coming out on the importance of the microbiome, how it influences all elements of health from your mood to your skin to you name it. I think it’s an extremely exciting industry. Not to mention that fermented foods are popping up everywhere. Look at kombucha, look at fermented, plant-based yogurts. They’re everywhere. I think it’s one of the hottest trends.

Q: What challenges do fermented food producers face?

From the manufacturing side, it’s hard to scale a fermented food. It’s hard to scale any manufacturing product, but with fermented food, there’s value in having a smaller volume. It’s also a living organism, it’s really a living thing with a personality that you really need to really thoughtfully think of how to scale. You also just have to learn from your mistakes, it’s just a trial by error thing. It’s a growing category and there’s a ton of competition.

Q: What are the fermented food industry strengths?

I think the entire ecosystem of retail is going to healthy food, functional food, slow food. When you look at Wal-Mart being the largest seller of organic products, that’s exciting. That’s correlated to the fact that people want to eat healthy. Fermentation is a staple and tiller of health in every single culture, you name it. Every corner of the world has fermented food.

Q: Where do you see the future of the fermented food industry?

I think the future would be people being a household necessity to the point where people are trying to get a form of fermented food in their diet every single day. It’s becoming a preventative medicine, and that’s promising.

Q: What’s your advice to other entrepreneurs starting a fermentation brand?

Start small and don’t grow too fast. We’ve had some serious growing pains, and just really try to add value to the product, listen to your consumer, and you get in front of it as many consumers as you can and gather feedback so you can find your niche.

And also, tap into the community. What excites me the most about fermentation and food in general is there’s so many people willing to help and provide advice.

Q: What can the fermentation industry do to better educate the public about fermented foods?

The onus is on, the brands. this was one of the reasons I started a food company, people vote with their dollars. And the best was to educate is to create a really good product.

- Published in Business, Food & Flavor

Bubbling Over: 3 Fermenters on the Future of Fermentation Industry

We asked the co-founders of three fermentation brands where they see the future of the fermentation industry. Though all noted consumers are seeking fermented products for health properties, these brand leaders all gave their own interesting insight into fermentation’s growth.

Where do you see the future of the fermentation industry?

Obviously, you have a lot of beverages out there that really paved the way, kombucha has been a huge success story. But fermented vegetables I think are, one, you’re getting a ton of free press from dietitians and doctors who are saying you need to eat this stuff, the rest of the world eats this every day, Americans need to eat it, too. Second, gut health is tied into everything, and that’s pushing fermented product sales. There are studies proving gut health is linked to your mental well-being, its liked to weight managements, its linked to your skin health. Then third, exciting flavors and new and exciting brands. Fermented products need to be approachable products for the American palate, and I’m proud to say that we’re a big driver of that. We’re showing what can be done with a simple product.

Drew Anderson, Cleveland Kraut

I think it’s only going to go up from here. I see it really booming in a big way. I see a lot of activity happening in the future with new companies coming up on the horizon. I also am excited for the gut-brain connection, how ferments can really affect mental health disorders, like depression and bipolar and anxiety. I think that’s a field that were not even breaking into at all and it’s coming.

I think we’re pretty far from this but I think fermented foods can be incredibly potent in preventative medicine as well, like preventing certain diseases that are on the rise, like diabetes and cancer. I don’t want to make health claims, but i think that’s where we’re going with the industry.

Lauren Mones, Fermenting Fairy

The trend is going to continue, that people are going to continue to eat more fermented foods, that they’re going to eat more diverse and types of fermented foods that will be in the American diet. I think people are going to start caring more about where their food comes from. Fermented foods that come from farmers and soil that is improving and helping climate change rather than contributing to it. We only have about 12 more years to figure that out. People are going to really start to understand that and make choices based on that.

- Published in Food & Flavor

MSG Myth Busting, Award-Winning Chefs Tout Benefits of Flavor Enhancer

In the next wave of “health” advocates slamming MSG, this week customers are upset Chick-fil-A includes MSG in their fried chicken. MSG often gets a bad rep as a preservative, but it’s a sodium salt naturally occurring in the human body and in whole foods (like tomatoes, mushrooms and potatoes). MSG is a umami-packed flavor enhancer that can be made as a flavoring agent through a fermentation process. Award-winning fermentation chefs like David Chang of Momofuku and David Zilber of NOMA use MSG in their dishes. A Today show article busts some of the common myths around MSG.

Read more (Today)

- Published in Food & Flavor

Master Fermenter David Chang’s Media Empire Expands to Hulu Food-Centric Talk Show

Superchef David Chang is transforming his restaurant business into a multimedia empire. The restauranteur, author, publisher, TV celebrity and podcast host announced this month that he’s adding another television gig to his resume: “Family Style.” Chang will co-host the food-centric talk show with celebrity and cookbook author Chrissy Teigen.

“We’re not trying to promote the restaurant; we’re trying to promote our ideals. And I think, to the younger generation, that’s more important to them than ever before,” Chang said at Recode’s Code Conference.

The Korean-American founder of Momofuku restaurant is known for shaking up the restaurant industry with cutting-edge culinary innovations. A major proponent of fermentation, Chang’s innovation in the cooking technique has propelled fermentation’s recent renaissance in America. In his Kaizen Trading Company fermentation lab, Chang develops his own line of fermented products for restaurants.

Chang aims for his media projects to reflect the values of the restaurants he’s created all over the world – authentic and honest. He compared starting a food-based media company, Majordomo Media, to chef Wolfgang Puck’s entrepreneurship. Puck “created a giant business of every kind of thing related to food,” like consumer-packaged goods, cookware and catering.

“If the media takes off, that’s more stuff we can bring back to the restaurants,” Chang said. The media arm feeds his restaurants. “Maybe people will never want to pay that much money for [Momofuku] food, maybe we can subsidize some of the costs with [the media projects] that’s alleviating our bills.”

Changing Kitchen Atmosphere

Majordomo Media produces the Netflix series “Ugly Delicious” and the podcast “The David Chang Show.” Chang won’t discuss viewership numbers. But he says the exposure has made Momofuku busier than ever, and that’s not because the restaurant is featured heavily in the TV show. It’s the message about the food industry and corporate responsibility that sticks with viewers, piquing their interest in Momofuku.

“Everyone has an understanding of food now; the food awareness is higher than ever before,” Chang said. “But no one quite wants to understand how that food gets made. They understand maybe from an environmental perspective, but they don’t understand it from a restaurant perspective.”

Customers should make themselves aware of restaurant ownership, especially in a post #MeToo world when sexual assault accusations have put into light the deplorable behavior of restauranteurs like Mario Batali.

Important, too, are proper working conditions. The culinary industry is historically a “brutish system,” Chang said. The hours are long and tiring. Today’s labor force is changing workplace culture, though. Millennial employees are disrupting the horse race work pace, they are “allergic to the working conditions and the stress that we were creating.”

“You work long hours in the culinary world, and I’ve always believed that the culinary world and those that lead people in the culinary world have maybe one of the hardest jobs because you can’t motivate people with a giant stock option package or a giant bonus that you might get on Wall Street. You have to motivate someone to do physical hard labor and to try and get better at that through sheer integrity and personal will and that’s hard, that’s incredibly hard to motivate people,” Chang said.

He added: “How do you balance out what’s essentially still a blue-collar labor, which is cooking, [that] is now glamourized to a point that it now has white-collar values? That’s a collision that’s hard to mitigate and sort out.”

Chang’s creating that white-collar environment at his restaurants, giving vacation days, mandatory breaks and a shift drink at the end of a service. He wants to professionalize the restaurant industry when, historically, it’s never been professional.

“I’ve been so allergic to a corporate body for so many years, but now I think I’ve convinced myself it’s the only way to go,” Chang said.

Experimental Triumphs & Failures

Lauded as the bad boy in the food world, Chang is a chef willing to take unapologetic risks. His innovation has not come without failures, though. Lucky Peach, the award-winning food magazine he co-founded, shuttered after creative differences. Maple, a New York food service Chang backed that prepared and delivered gourmet food, folded amidst massive debt. Ando, another Chang backed food delivery service, suddenly closed, then was acquired by Uber Eats. Chang closed Má Pêche last year, citing declining foot traffic around New York’s midtown thanks to extra security at Trump Tower. New York Italian restaurant Momofuku Nishi closed too after a touch review, then remodeled and reopened.

That review – by Pete Wells of the New York Times – was Momofuku’s first bad review. It destroyed the restaurant, Chang said. But he added that he’s weirdly thankful for that review because it helped Momofuku reevaluate, “our restaurants around the world are doing better than before because of that review.”

“My fear is that once you become too systemized in the restaurant industry, you’re going to lose any of the coolness, creative parts,” Chang said. “I got into cooking because it wasn’t cool. Everyone thought it was career suicide when I said ‘Hey I’m going to start to cook,’ it was sort of that sense of danger, that sense of recklessness that no longer really exists.”

“It’s completely different than a tech business because scaling a brand in food, yes, it can work in McDonald’s or if you have a beverage,” Chang said. “But the idea of scaling something that’s intimate, some kind of contract between you and a prospective diner, that’s hard because we’re still trying to be best in class in making the most thoughtful, delicious food and it’s hard to scale excellence I think.”

(Photo by Wall Street Journal)

- Published in Food & Flavor